Submitted:

25 June 2024

Posted:

27 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The NARP Cells (Cybrids) and Parental 143B Cells

2.2. Measurement of Cell Viability Using the MTT Assay

2.3. Preparation of the Cells for Imaging

2.4. Chemical and Fluorescent Dye Loading for Fluorescence Measurement of Mitochondrial Events

2.5. Imaging Analysis of Living Cells

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Assessing Cell Viability under Different Stress Conditions

3.2. Determining the Toxicities of High Glucose and Mitochondrial Calcium (Ca2+)m Overload on 143B Cells and NARP Cybrids

3.3. Depicting How Mitochondrial Calcium Overload [Ca2+]m Modulates High Glucose Toxicity on Respiratory Chain– Defect Augmented Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production and Membrane Potential (ΔΨ) Depolarization in Parental 143B Cells and NARP Cybrids

3.4. Depicting How Mitochondrial Calcium Overload [Ca2+]m Modulates High Glucose Toxicity on Respiratory Chain – Defect Augmented Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production and Membrane Potential (ΔΨ) Depolarization in Parental 143B Cells and NARP Cybrids under Antioxidant Conditions

3.5. Demonstrating How Mitochondrial Calcium Overload Modulates High Glucose Toxicity on Respiratory Chain Defect Augmented Mitochondrial Cardiolipin (CL) Remodeling and Calcium (Ca2+) Homeostasis in Parental 143B Cells and NARP Cybrids under Ca2+ Treated Hepex Conditions

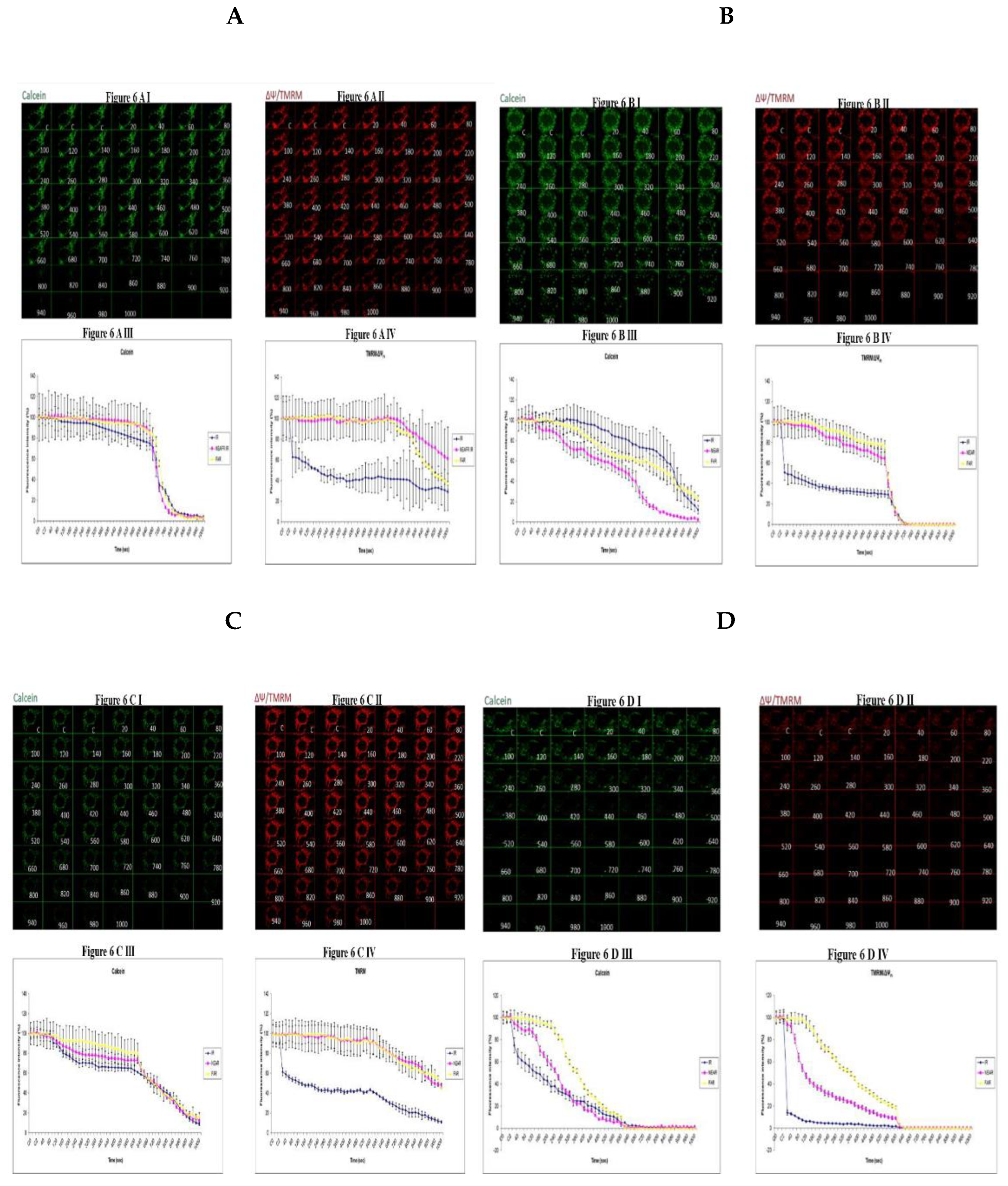

3.6. Investigating How High Glucose Augment Respiratory Chain Defect Augmented Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore (MPTP) Including Transient (t-MPT) and Permanent (p-MPT) on Parental 143B Cells and NARP Cybrids

4. Discussion

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Brownlee, M. , Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature, 2001. 414(6865): p.813-20. [CrossRef]

- Green, K., M. D. Brand, and M.P. Murphy, Prevention of mitochondrial oxidative damage as a therapeutic strategy in diabetes. Diabetes, 2004. 53 Suppl 1: p. S110-8. [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T. , et al., Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature, 2000. 404(6779): p. 787-90. [CrossRef]

- Van den Berghe, G. , How does blood glucose control with insulin save lives in intensive care? J Clin Invest, 2004. 114(9): p. 1187-95.

- Kemppainen, E. , et al., Mitochondrial Dysfunction Plus High-Sugar Diet Provokes a Metabolic Crisis That Inhibits Growth. PLoS One, 2016. 11(1): p. e0145836.

- Chen, H. and D.C. Chan, Emerging functions of mammalian mitochondrial fusion and fission. Hum Mol Genet, 2005. 14 Spec No. 2: p. R283-9. [CrossRef]

- Vanhorebeek, I. , et al., Protection of hepatocyte mitochondrial ultrastructure and function by strict blood glucose control with insulin in critically ill patients. Lancet, 2005. 365(9453): p. 53-9. [CrossRef]

- Cai, D. , Neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in overnutrition-induced diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2013. 24(1): p. 40-7. [CrossRef]

- Kahn, S.E., M. E. Cooper, and S. Del Prato, Pathophysiology and treatment of type 2 diabetes: perspectives on the past, present, and future. Lancet, 2014. 383(9922): p. 1068-83. [CrossRef]

- Szkudelski, T. , Streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced diabetes in the rat. Characteristics of the experimental model. Exp Biol Med (Maywood), 2012. 237(5): p. 481-90.

- Somesh, B.P. , et al., Chronic glucolipotoxic conditions in pancreatic islets impair insulin secretion due to dysregulated calcium dynamics, glucose responsiveness and mitochondrial activity. BMC Cell Biol, 2013. 14: p.31. [CrossRef]

- Duchen, M.R. , Mitochondria and calcium: from cell signalling to cell death. J Physiol, 2000. 529 Pt 1: p. 57-68. [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, D.R. and N.J. Gardiner, Glucose neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2008. 9(1): p. 36-45. [CrossRef]

- Lamb, C.A., T. Yoshimori, and S.A. Tooze, The autophagosome: origins unknown, biogenesis complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2013. 14(12): p. 759-74. [CrossRef]

- Altshuler-Keylin, S. and S. Kajimura, Mitochondrial homeostasis in adipose tissue remodeling. Sci Signal, 2017.10(468). [CrossRef]

- Liesa, M. and O.S. Shirihai, Mitochondrial dynamics in the regulation of nutrient utilization and energy expenditure. Cell Metab, 2013. 17(4): p. 491-506. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Otin, C. , et al., The hallmarks of aging. Cell, 2013. 153(6): p. 1194-217.

- Park, J.T. , et al., Adjustment of the lysosomal-mitochondrial axis for control of cellular senescence. Ageing Res Rev, 2018. 47: p. 176-182. [CrossRef]

- Schlame, M., D. Rua, and M.L. Greenberg, The biosynthesis and functional role of cardiolipin. Prog Lipid Res, 2000. 39(3): p. 257-88. [CrossRef]

- Lange, C. , et al., Specific roles of protein-phospholipid interactions in the yeast cytochrome bc1 complex structure. EMBO J, 2001. 20(23): p. 6591-600. [CrossRef]

- Koshkin, V. and M.L. Greenberg, Cardiolipin prevents rate-dependent uncoupling and provides osmotic stability in yeast mitochondria. Biochem J, 2002. 364(Pt 1): p. 317-22. [CrossRef]

- Ott, M. , et al., Cytochrome c release from mitochondria proceeds by a two-step process. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2002. 99(3): p. 1259-63. [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, K. , et al., Cardiolipin stabilizes respiratory chain supercomplexes. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(52): p. 52873-80. [CrossRef]

- DiMauro, S. and E.A. Schon, Mitochondrial respiratory-chain diseases. N Engl J Med, 2003. 348(26): p. 2656-68. [CrossRef]

- Yu, T., B. S. Jhun, and Y. Yoon, High-glucose stimulation increases reactive oxygen species production through the calcium and mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated activation of mitochondrial fission. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2011. 14(3): p. 425-37. [CrossRef]

- Baracca, A. , et al., Catalytic activities of mitochondrial ATP synthase in patients with mitochondrial DNA T8993G mutation in the ATPase 6 gene encoding subunit a. J Biol Chem, 2000. 275(6): p. 4177-82. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K. and J. Han, Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Disorders. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2017. 982: p. 621-646. [CrossRef]

- Jou, M.J. , Pathophysiological and pharmacological implications of mitochondria-targeted reactive oxygen species generation in astrocytes. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2008. 60(13-14): p. 1512-26. [CrossRef]

- Huser, J., C. E. Rechenmacher, and L.A. Blatter, Imaging the permeability pore transition in single mitochondria. Biophys J, 1998. 74(4): p. 2129-37. [CrossRef]

- D'Aurelio, M. , et al., Mitochondrial DNA background modifies the bioenergetics of NARP/MILS ATP6 mutant cells. Hum Mol Genet, 2010. 19(2): p. 374-86. [CrossRef]

- Carrozzo, R. , et al., The T9176G mtDNA mutation severely affects ATP production and results in Leigh syndrome. Neurology, 2001. 56(5): p. 687-90. [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.I. , et al., mtDNA T8993G mutation-induced mitochondrial complex V inhibition augments cardiolipindependent alterations in mitochondrial dynamics during oxidative, Ca(2+), and lipid insults in NARP cybrids: a potential therapeutic target for melatonin. J Pineal Res, 2012. 52(1):p. 93-106.

- De Meirleir, L. , et al., Respiratory chain complex V deficiency due to a mutation in the assembly gene ATP12. J Med Genet, 2004. 41(2): p. 120-4. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.Y., M. J. Jou, and T.I. Peng, mtDNA T8993G mutation-induced F1F0-ATP synthase defect augments mitochondrial dysfunction associated with hypoxia/reoxygenation: the protective role of melatonin. PLoS One, 2013. 8(11): p. e81546. [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.J. , et al., Mitochondrial networking protects beta-cells from nutrient-induced apoptosis. Diabetes, 2009. 58(10): p. 2303-15.

- Youle, R.J. and A.M. van der Bliek, Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science, 2012. 337(6098): p. 10625.

- Shefa, U. , et al., Mitophagy links oxidative stress conditions and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen Res, 2019. 14(5): p. 749-756. [CrossRef]

- Bhansali, S. , et al., Alterations in Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress and Mitophagy in Subjects with Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2017. 8: p. 347. [CrossRef]

- Jou, M.J., T. I. Peng, and R.J. Reiter, Protective stabilization of mitochondrial permeability transition and mitochondrial oxidation during mitochondrial Ca(2+) stress by melatonin's cascade metabolites C3-OHM and AFMK in RBA1 astrocytes. J Pineal Res, 2019. 66(1): p. e12538.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).