Submitted:

26 June 2024

Posted:

27 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To address the issue of BERT’s inability to effectively utilize address spatial semantics at the embedding layer, we propose a lexicon-enhancement method based on hybrid representation. This method transforms the address spatial semantics extracted by ASSE into a symbolic semantic space, achieving the fusion of address spatial semantics with the BERT-based deep parsing model at the model level.

- (2)

- To tackle the problem of insufficient integration of spatial semantics within the BERT model, we introduce a spatial semantics-enhanced lexicon adapter. This adapter incorporates address spatial semantics into the Transformer layers of the BERT model, realizing effective fusion of spatial semantics within the BERT layers and the BERT-based deep parsing model.

- (3)

- We design a BERT-based deep model that integrates address spatial semantics (Address Spatial Semantics Fusion Deep Parsing Model, ASSPM), demonstrating its outstanding performance in high-resource scenarios. This model excels in Chinese address parsing tasks, promising to enhance the performance of address parsing models in practical applications, especially in scenarios requiring substantial data and hardware resources. This provides a robust solution for address parsing tasks.

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

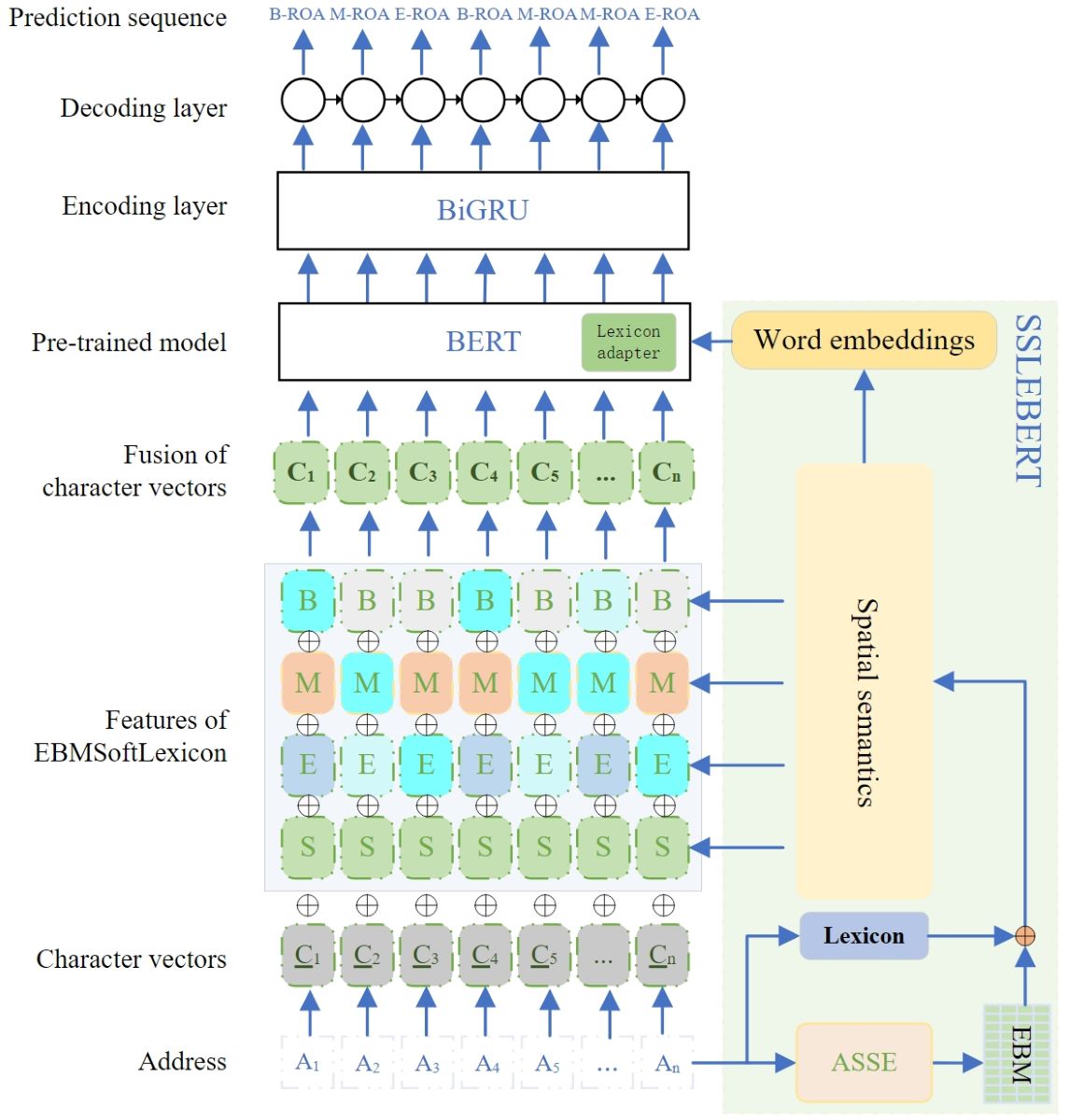

3.1. Model Framework

3.2. ASSE

3.3. Spatial Semantic Representation Fusion Module

- (1)

-

Character Representation LayerFor Chinese parsing models based on character-level representations, the input sentence is treated as a sequence of characters, denoted as , where is the character vocabulary [15]. Each character is represented as a vector, as shown in Equation (1):where denotes the character embedding lookup table.Zhang and Yang [14] demonstrated that character bigrams can effectively enhance character representations. Therefore, character bigrams are constructed and concatenated with the vector representation of character , as shown in Equation (2):where represents the bigram character embedding lookup table. This results in the basic character vector representation. Next, methods to enhance it through the incorporation of dictionary information are discussed.

- (2)

-

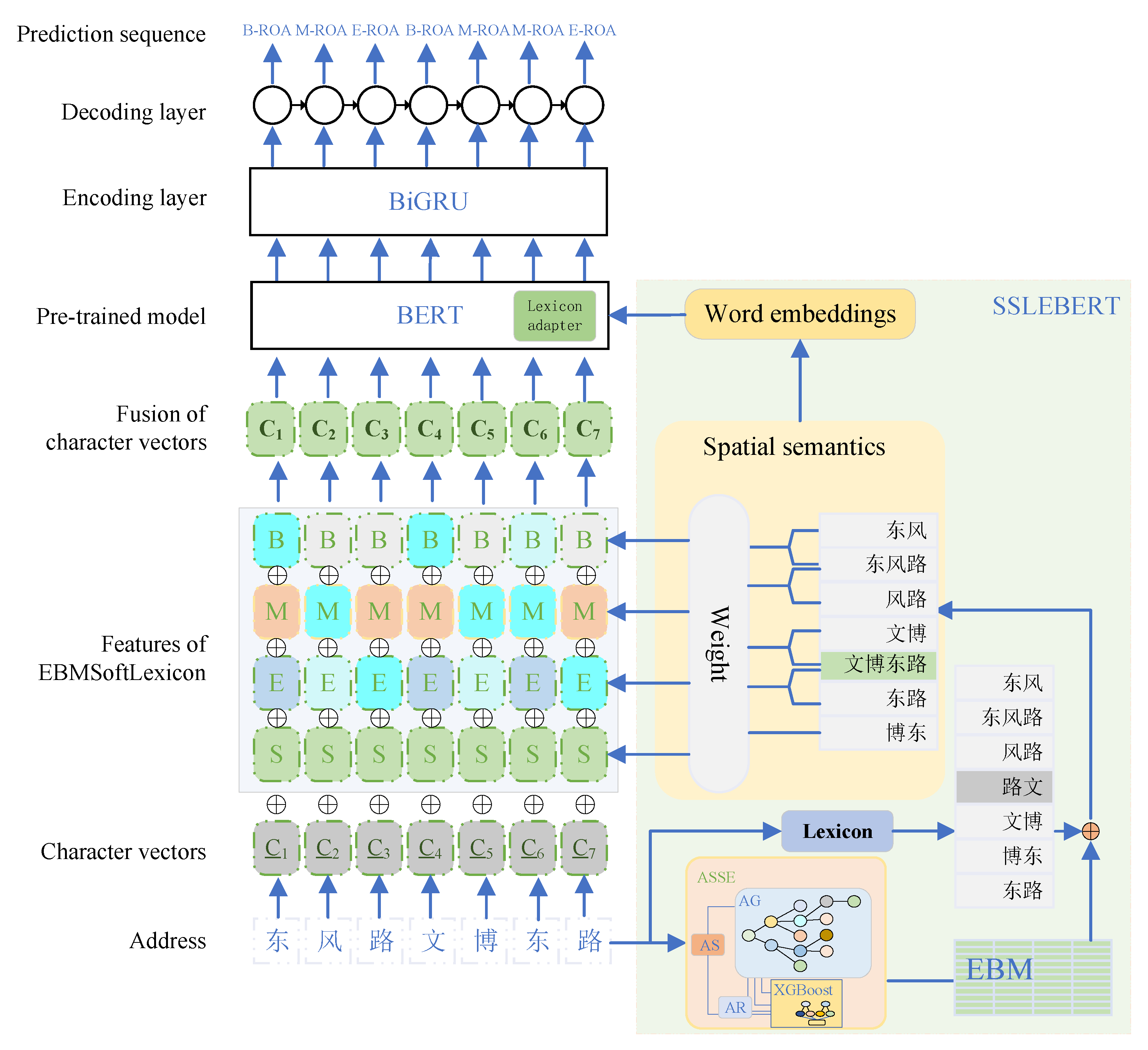

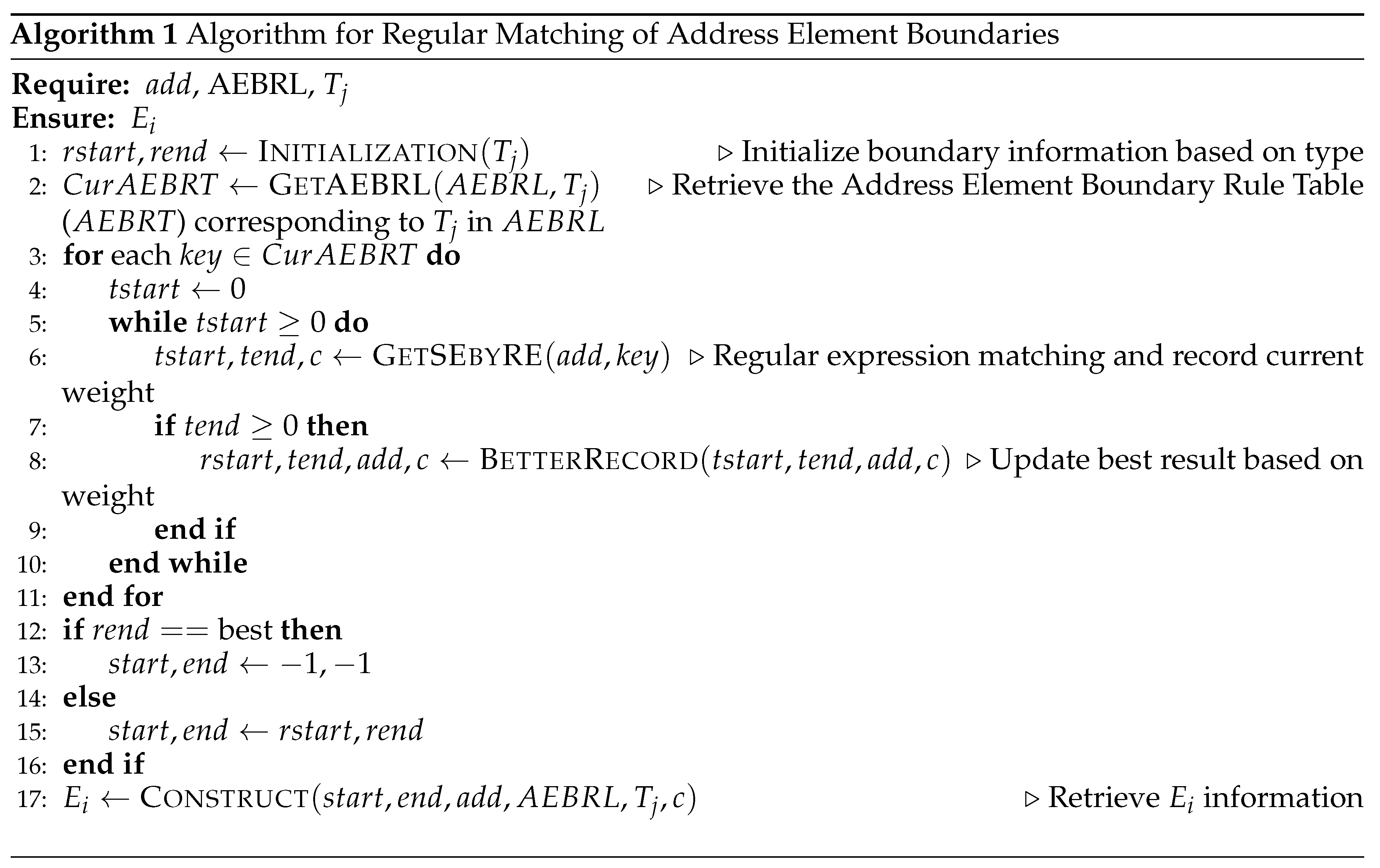

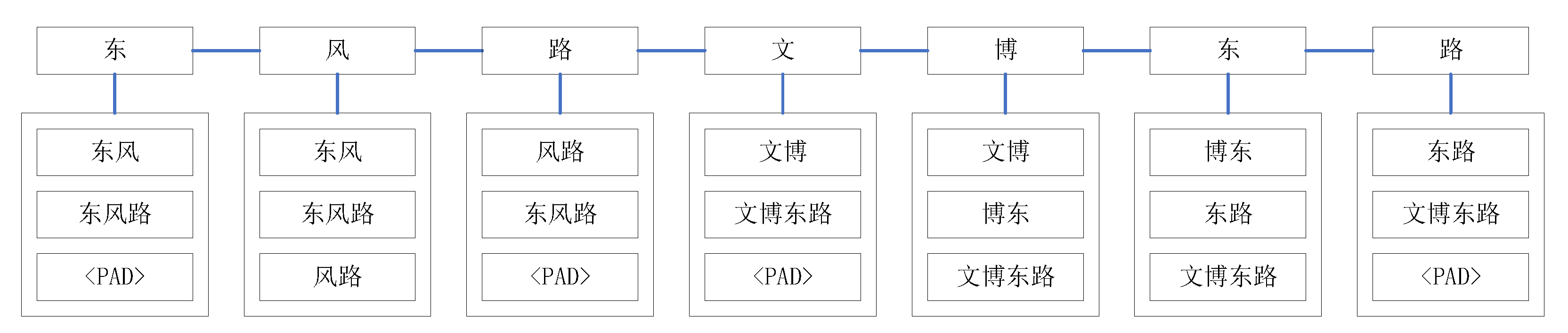

Incorporating lexical informationBelow we discuss methods to integrate lexical information into . To address the limitation of character-based NER models in utilizing lexical information, Ma et al. [15] proposed two approaches: ExSoftword and SoftLexicon. Before delving into these methods, let’s first discuss the representation of words: for any input character sequence , introduce the symbol to denote the subsequence . Next, we will discuss three methods for integrating lexical information: ExSoftword, SoftLexicon, and EBMSoftLexicon.ExSoftword: As an extension of Softword [24,25], ExSoftword not only retains one segmentation result for each character after segmentation but obtains all possible segmentation results from the lexicon, as shown in Equation (3):where represents all classification labels related to . For example, for the character “江”(River) in Figure 1, which appears as both a middle and an end character, . is a 5-dimensional multi-hot vector, with each dimension corresponding to {B, M, E, S, O}.ExSoftword faces two challenges [15]: 1) It cannot utilize pre-trained word models. 2) It suffers from missing matching information, leading to multiple matching results.SoftLexicon:To address the aforementioned issues, SoftLexicon [15] offers a solution that involves three primary steps:Firstly, in the initial step, the matched vocabulary is categorized. To retain segmentation information, each character matched to a word is classified into {B, M, E, S}. For each character , the four sets are defined as follows in Equation (4):where L denotes the dictionary used in this study. If no vocabulary information matches, it is replaced with "None". This approach embeds words while mitigating information loss.Secondly, the sets {B, M, E, S} of vocabulary vectors are compressed into fixed-dimensional vectors. After obtaining the sets B, M, E, S for each character, they are compressed into fixed-dimensional vectors in two ways. The first approach is to directly average them, as shown in Equation (5):where U represents the set of vocabulary, i.e., the set of vocabulary, and represents the word embedding.At the same time, in order to maintain computational efficiency, dynamic weighted algorithms such as attention mechanisms have not been adopted. Ma et al. [15] suggested using frequency to represent the weight of each word. Since the frequency of a word can be obtained offline as a static value, this significantly improves the efficiency of calculating the weight of each word. The literature confirmed that the compression method implemented by Equation (5) is not ideal.Next, the second approach is discussed. Specifically, let represent the frequency at which the word w appears in the dictionary. Thus, the weighted representation of the set U can be obtained, as shown in Equation (6):where . If w is covered by another subsequence matching the dictionary, the frequency of w will not increase. This prevents the problem where the frequency of shorter words is always smaller than that of longer words covering them.Finally, the third step involves merging character representations. Once the fixed-dimensional representations of the four vocabulary sets are obtained, they can be combined into a fixed-dimensional feature, as shown in Equation (7):where is the weighted function provided by Equation (6). Thus, Equation (7) yields the SoftLexicon character representation, as shown in Equation (8):EBMSoftLexicon:While SoftLexicon has demonstrated significant performance, particularly showcasing its potential in low-resource scenarios, for Chinese address parsing tasks, this approach introduces some unnecessary lexical information. For instance, in the context of “东风路”(Dongfeng Road) depicted in Figure 1, the lexical information for “东风”(Dongfeng) could be filtered out entirely due to the prominent tail feature of the character “路”(road). Similarly, “文博”(Wenbo) and “博东”(Bo East) serve as examples of irrelevant “interference” information that does not need consideration. To address the challenges identified, an enhanced method called EBMSoftLexicon is proposed to integrate lexical information more effectively, particularly for Chinese address parsing tasks. This method combines the SoftLexicon approach with Address Element Boundary Matrix (EBM) information derived from ASSE. This integration aims to refine or enhance SoftLexicon by incorporating boundary information, confidence scores, and evaluation metrics from EBM.Specifically, the approach involves calculating a weighted vector representation for each vocabulary word w, as defined in Equation (9):where and are determined by Equations (10) and (11), respectively.In equation (11), represents an 8-dimensional input vector, specifically the address state, composed of address element type, transition probability, length information, matching start and end positions, regular expression score, matching length, and a numeric indicator (1 for Chinese and Arabic numerals, 0 otherwise). P denotes the parameters of the XGBoost, with the experimental section detailing the configuration of these parameters to obtain P. denotes the function that converts the input vector into a DMatrix data structure. refers to the XGBoost trained using the parameters P, and is the function used to make predictions with the trained model.denotes the annotated dataset. Correspondingly, let , which allows us to obtain the weighted representation of the word set U in EBMSoftLexicon, as shown in equation (12):Here, indicates that the EBM score surpasses the threshold, allowing for enhanced embedding using and . If the condition is not met (else case), or for non-Chinese address data where EBM information isn’t applicable, a fallback to SoftLexicon embedding occurs.EBMSoftLexicon is obtained offline through ASSE. This method first uses ASSE to extract all Chinese addresses’ EBM from the annotated dataset. This extraction differs slightly from the original data extraction because basic information can be obtained directly from the annotation information, such as the matching targets and address element boundary types in equation (13). This significantly reduces the complexity of solving and allows evaluation information to be obtained through the evaluation mechanism in the extractor. Then, equation (9) is used to obtain the weights of all vocabulary in the current dataset. It is important to note that vocabulary exists in two forms: complete address elements represented by EBM column vectors, and boundary information contained in EBM. In cases where both forms exist, preference is given to the former due to its inclusion of the latter.Here, represents the address text, denotes a specific address element type, and extracts boundary information using and . The function P combines the results of into , which populates the first seven dimensions of . The function is detailed in Algorithm 1:

Finally, substituting equation (12) into equations (7) and (8), the EBMSoftLexicon character representation is obtained as shown in equation (14):In summary, EBMSoftLexicon not only avoids introducing unnecessary or "noise" information directly from dictionary lookups, but also leverages boundary and spatial distribution information effectively. By obtaining vocabulary information from ASSE, which includes evaluation scores and confidence levels, when EBM is not obtained or the obtained EBM has insufficient scores (corresponding to the case in equation (12)), the solution follows equation (6). Therefore, the EBMSoftLexicon represented by equation (14) is compatible with SoftLexicon, contributing to enhanced model stability. This approach achieves a blended representation of spatial semantics and deep parsing models through enhanced embedding layers.

Finally, substituting equation (12) into equations (7) and (8), the EBMSoftLexicon character representation is obtained as shown in equation (14):In summary, EBMSoftLexicon not only avoids introducing unnecessary or "noise" information directly from dictionary lookups, but also leverages boundary and spatial distribution information effectively. By obtaining vocabulary information from ASSE, which includes evaluation scores and confidence levels, when EBM is not obtained or the obtained EBM has insufficient scores (corresponding to the case in equation (12)), the solution follows equation (6). Therefore, the EBMSoftLexicon represented by equation (14) is compatible with SoftLexicon, contributing to enhanced model stability. This approach achieves a blended representation of spatial semantics and deep parsing models through enhanced embedding layers.

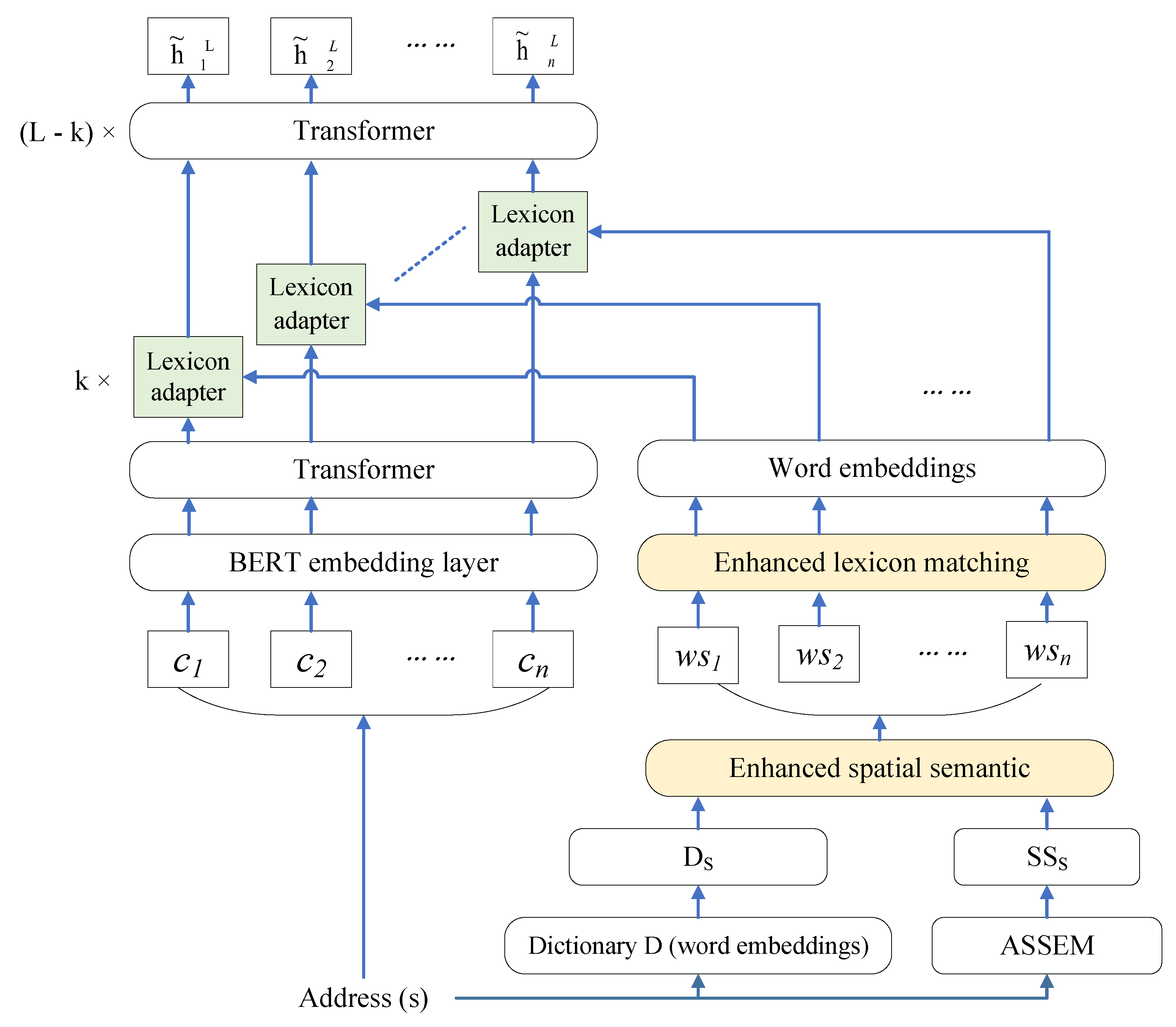

3.4. Spatial Semantic Lexicon Enhanced BERT Module

- (1)

-

Enhanced Spatial Semantics of Character-Word PairsA Chinese sentence is typically represented as a sequence of characters, which only captures character-level features. To incorporate lexical information, the character sequence is expanded into a sequence of character-word pairs. Given a Chinese dictionary and a sentence consisting of n characters, potential words in the sentence, denoted as , are identified by matching the character sequence with . Specifically, a Trie tree is constructed based on , and all possible character subsequences in the sentence are matched against this Trie tree to obtain all potential words, denoted as . To enhance spatial semantics representation, lexical elements from the dictionary and address features extracted by the ASSE are utilized. denotes the vocabulary sequence obtained by ASSE, referred to as spatial vocabulary sequence. For each address, each corresponding is sequentially searched within for substring matches. Words in that cannot be found in are removed, and finally, the union operation is applied between and . The spatial semantics-enhanced character-word pairs corresponding to the addresses in Figure 1 are illustrated in Figure 3.

- (2)

-

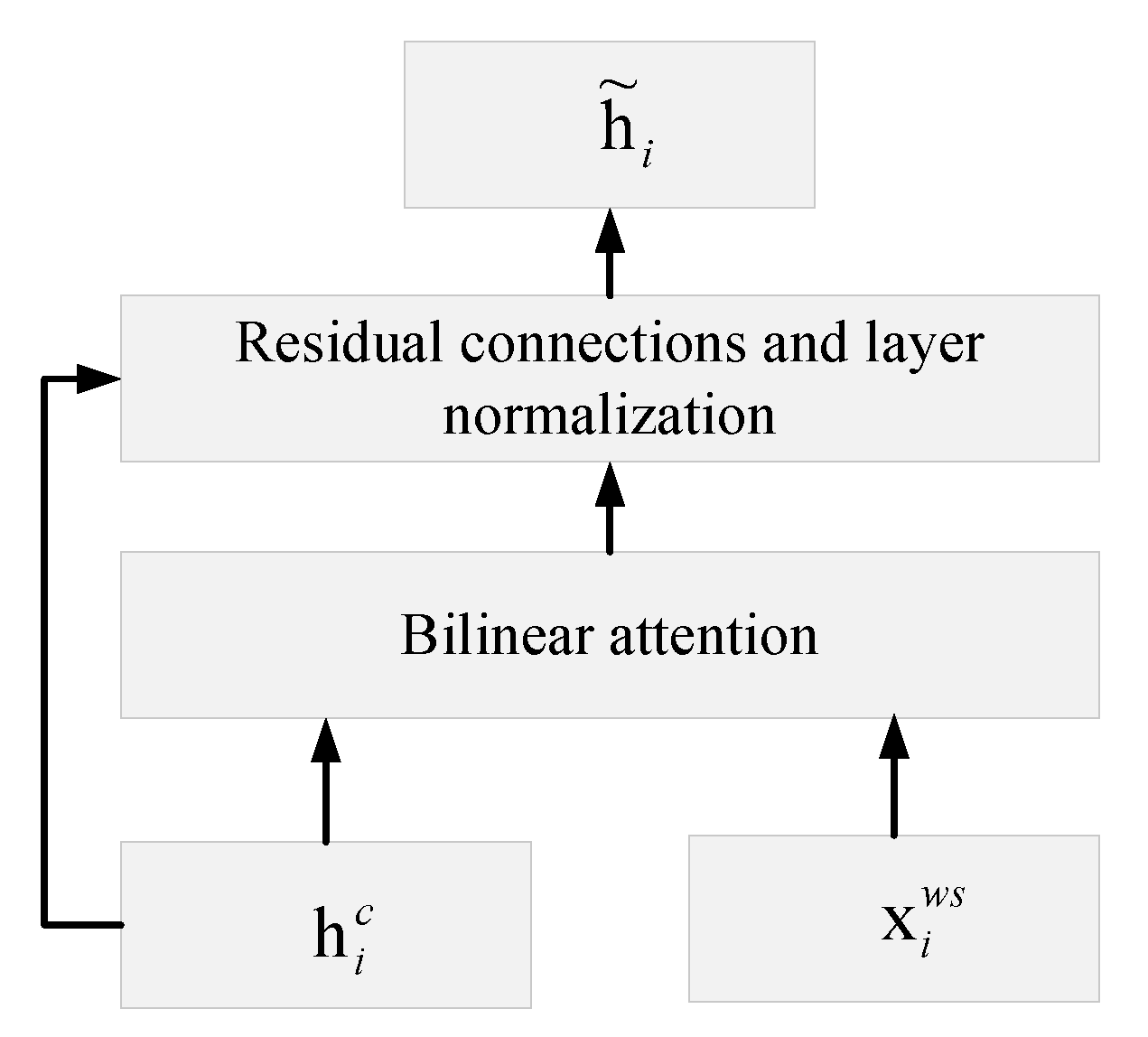

Lexicon AdapterEach position in every sentence contains two distinct types of information: character-level and word-level features. Consistent with existing hybrid model approaches, this study aims to effectively integrate lexicon features with BERT. The Lexicon Adapter (LA) [20], depicted in Figure 4, illustrates this integration process.The Lexicon Adapter accepts two inputs: character vectors and their corresponding word embeddings. At the i-th position in the character-word pair sequence, inputs are represented as , where is the character vector obtained from a Transformer layer of BERT, and is a set of word embeddings. The j-th word in is represented as shown in Equation (15):where is a pre-trained word embedding lookup table and is the j-th word in . It’s important to note that the Address Semantic Extractor (ASSE) may yield words in that are not in the vocabulary. In such cases, these words are split into multiple components and their corresponding word vectors are looked up individually using Equation (12).To ensure compatibility between these two representations, a nonlinear transformation is applied to the word vectors, as shown in Equation (16):where is a matrix, is a matrix, and and are scalar biases. and represent the dimensions of word embeddings and BERT’s hidden layers, respectively.As depicted in Figure 3, each Chinese character corresponds to multiple words. However, each word contributes differently to each task. To select the most relevant words from all matched words, a character-to-word attention mechanism is introduced. All assigned to the i-th character are represented as , where m is the total number of assigned words. The relevance of each word can be calculated using Equation (17):where is the weight matrix for bilinear attention. Thus, the weighted sum of all words is obtained using Equation (18):Finally, the weighted lexicon information is injected into the character vector using Equation (19):

- (3)

-

Lexicon-Enhanced BERTLexicon-Enhanced BERT (LEBERT) combines the Lexicon Adapter (LA) with BERT, where LA is applied to a specific layer of BERT to incorporate external lexicon knowledge into the model. Given a Chinese sentence , we construct the corresponding character-word pair sequence .Firstly, the characters are input into the input embeddings, which include token, segment, and positional embeddings, resulting in . These embeddings E are then passed through the transformer encoder, where each transformer layer operation is defined as in Equation (20):where represents the output of the l-th layer, ; LN denotes layer normalization; MultiHeadAttention refers to the multi-head attention mechanism; FFN denotes a two-layer feed-forward network with ReLU as the hidden activation function.To inject lexicon information between the k-th and -th Transformer layers, we first obtain the output after passing through k consecutive Transformer layers. Then, each pair is processed through the Lexicon Adapter, transforming the i-th pair into , as shown in Equation (21):Given that BERT consists of Transformer layers, is then input into the remaining Transformers, resulting in the output of the L-th Transformer for sequence labeling tasks.

3.5. Encoding-Decoding and Loss Function

4. Experiment

4.1. Dataset Processing

4.2. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Comparison with Baseline Methods

- (1)

- Lattice-LSTM: Zhang et al. [14] introduced the Lattice-LSTM model at the ACL conference in 2018. This model aims to address issues faced by character-based and word-based methods. It jointly encodes characters of input sequences and their potential words from a dictionary into a lattice structure. Compared to character-based methods, Lattice-LSTM explicitly utilizes lexical and sequential information. Unlike word-based methods, it avoids segmentation errors since it does not require segmentation operations.

- (2)

- ALBERT-BiGRU-CRF: Introduced by Lan et al. [26] in 2020, ALBERT-BiGRU-CRF is based on the BERT pre-trained language representation model. This model enhances performance by incorporating fixed-length context into input sequences and employs bidirectional encoder representations within a Transformer architecture. Compared to traditional BERT models, ALBERT has fewer parameters and achieves excellent results across various NLP tasks, thereby advancing research and applications in the NLP field.

- (3)

- SoftLexicon-BERT: Ma et al. [15] proposed SoftLexicon in 2020, an innovative approach combining dictionaries with neural networks for Chinese Named Entity Recognition (NER). This method introduces SoftLexicon to share lexical information between encoder and decoder, thus improving overall performance.

- (4)

- BiGRU-CRF: Liu et al. [27] introduced this model in 2021, which integrates deep learning with traditional methods for Chinese address parsing. BiGRU-CRF utilizes the strong contextual memory of Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Units (Bi-GRU) to effectively handle unknown words and ambiguities without relying on dictionaries or manual features. The Conditional Random Field (CRF) layer ensures reasonable output labeling sequences. It excels in address parsing by handling patterns like intersection addresses and spatially vague offsets. Using a five-word tagging method enhances granularity for subsequent matching and positioning operations.

- (5)

- LEBERT: Liu et al. [20] proposed LEBERT in 2021, which explores the integration of lexicon information with pre-trained models like BERT. Unlike existing methods that shallowly fuse lexicon features through a single shallow and randomly initialized sequence layer, LEBERT directly integrates external lexical knowledge into the BERT layer through a lexicon adapter layer, achieving deep fusion of lexicon knowledge and BERT representation for Chinese sequence labeling tasks.

- (6)

- GeoBERT: Liu et al. [28] introduced GeoBERT in 2021, a geographical information pre-training model. By constructing multi-granularity geographical feature maps, GeoBERT maps Points of Interest (POI) and various administrative regions into a unified graph representation space, embedding geographical information into text semantic space through predicting masked geographical information. This allows the model to learn geographical distribution characteristics for distinguishing different city POIs.

- (7)

- BERT-BiGRU-CRF: Lv et al. [29] proposed this model in 2022 for geographic named entity recognition based on deep learning. It combines BERT’s bidirectional encoder representations, Bidirectional GRU (BiGRU), and Conditional Random Field (CRF). The model utilizes pre-trained language models to construct integrated deep learning models, enriching semantic information in character vectors to improve the extraction capabilities of complex geographical entities.

- (8)

- BABERT: Jiang et al. [4] introduced BABERT in 2022, a pre-trained language model that enhances performance by introducing fixed-length context into input sequences and employing an unsupervised statistical boundary information method. Experimental results demonstrate BABERT’s stable performance improvement across various Chinese sequence labeling tasks. Additionally, BABERT serves as a complement to supervised dictionary exploration, potentially achieving better performance improvements by further integrating external dictionary information. During pre-training, the model learns rich geographical information and semantic knowledge, enabling accurate identification of key entities and assigning correct labels. Compared to traditional dictionary-based methods, BABERT better captures boundary information in addresses, thereby improving address parsing accuracy.

- (9)

- RoBERTa-BiLSTM-CRF: Zhang Hongwei et al. [30] proposed this method in 2022, combining deep learning for Chinese address parsing. It aims to solve problems with existing address matching methods that overly rely on segmentation dictionaries and fail to effectively identify address elements and their types. The model standardizes and analyzes address components post-parsing to enhance address parsing performance.

- (10)

- MGeo: Ding et al. [5] introduced MGeo in 2023, a multi-modal geographic language model containing a geographic encoder and a multi-modal interaction module. It views geographical context as a new modality and fully extracts multi-modal correlations to achieve precise query and matching functionalities.

4.4. Ablation Experiments

- (1)

- The effectiveness of EBMSoftLexicon in improving model performance is validated. The A-ESL model, which removes the character fusion module (EBMSoftLexicon), shows a decrease in F1 score by nearly 1.5%. This indicates that lexical information plays an important role in address text, and the character fusion module is crucial for enhancing model performance. By integrating lexical information, the character fusion module provides more accurate context understanding for the model, especially in handling complex address contexts.

- (2)

- A-SSLEBERT and A-S jointly demonstrate the effectiveness of SSLEBERT in improving model performance, emphasizing the significant research significance of the proposed enhanced spatial fusion method in Chinese address parsing tasks. The A-SSLEBERT model, by removing the spatial semantic lexicon enhanced BERT preprocessing model (SSLEBERT), shows a decrease in F1 score by approximately 1.2%. This underscores the effectiveness of SSLEBERT in enhancing model performance. This module enhances BERT’s representation by leveraging spatial semantic information, which is crucial for addressing complex contexts in Chinese address parsing tasks.

- (3)

- In different scenarios, the applicability of the spatial semantic lexicon to improving model performance is demonstrated. The A-S model, which replaces SSLEBERT with LEBERT, results in a decrease in F1 score by about 1%. The introduction of LEBERT further clarifies the effectiveness of the proposed method, especially in handling address information in different contexts.

- (4)

- In the last line’s A-BiGRU model, BiGRU plays a significant role. Removing this encoder results in a decrease in F1 score by nearly 1%, indicating that BiGRU significantly contributes to performance in address parsing tasks. Particularly in handling address information in different scenarios, BiGRU makes a notable contribution to performance improvement.

4.5. Results Discussion

5. Conclusion and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, S.; Li, Q.; Wei, F.; Zhou, X. Multi-source information fusion accident processing system based on knowledge graph. Journal of Shandong University of Technology (Natural Science Edition) 2024, 38, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lu, W.; Xie, P.; Li, L. Neural Chinese Address Parsing. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies(NAACL-HLT). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 3421–3431.

- Ling, G.; Mu, X.; Wang, C.; Xu, A. Enhancing Chinese Address Parsing in Low-Resource Scenarios through In-Context Learning. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2023, 12, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Long, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, P.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M. Unsupervised Boundary-Aware Language Model Pretraining for Chinese Sequence Labeling. Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 526–537. [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Chen, B.; Xie, P.; Huang, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y. MGeo: Multi-Modal Geographic Pre-Training Method. Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. ACM, 2023, pp. 185–194. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies(NAACL-HLT). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 4171–4186.

- Kang, M.; He, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, M.; Gao, Y. An Integrated Processing Strategy Considering Vocabulary, Structure and Semantic Representation for Address Matching. Journal of Earth Information Science 2023, 25, 1378–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Weinzierl, M.A.; Maldonado, R.; Harabagiu, S.M. The Impact of Learning Unified Medical Language System Knowledge Embeddings in Relation Extraction from Biomedical Texts. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2020, 27, 1556–1567. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, S.; Bai, J.; Song, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y. ZEN: Pre-training Chinese Text Encoder Enhanced by N-gram Representations. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics(EMNLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020, pp. 4729–4740. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, F.; Bao, H.; Hao, Y.; Zhou, P.; Xu, B. Joint Extraction of Entities and Relations Based on a Novel Tagging Scheme. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics(ACL); Association for Computational Linguistics: Vancouver, Canada, 2017; pp. 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru, O.; Can, O.A.; Yuret, D. CharNER: Character-Level Named Entity Recognition. Proceedings of COLING 2016, the 26th International Conference on Computational Linguistics: Technical Papers. The COLING 2016 Organizing Committee, 2016, pp. 911–921.

- Huang, Z.; Xu, W.; Yu, K. Bidirectional LSTM-CRF Models for Sequence Tagging. Computer Science - Computation and Language 2015.

- Tran, Q.; MacKinlay, A.; Yepes, A.J. Named Entity Recognition with Stack Residual LSTM and Trainable Bias Decoding. IJCNLP 2017, pp. 566–575.

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, J. Chinese NER Using Lattice LSTM. Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2018, pp. 1554–1564.

- Ma, R.; Peng, M.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, Z.; Huang, X.J. Simplify the Usage of Lexicon in Chinese NER. Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020, pp. 5951–5960.

- Li, Z.; Ding, N.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, H.; Shen, Y. Chinese Relation Extraction with Multi-Grained Information and External Linguistic Knowledge. Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 4377–4386.

- Gui, T.; Ma, R.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, Y.G.; Huang, X. CNN-Based Chinese NER with Lexicon Rethinking. Twenty-Eighth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence(IJCAI), 2019, pp. 4982–4988.

- Sui, D.; Chen, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J.; Liu, S. Leverage Lexical Knowledge for Chinese Named Entity Recognition via Collaborative Graph Network. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 3830–3840.

- Li, X.; Yan, H.; Qiu, X.; Huang, X.J. FLAT: Chinese NER Using Flat-Lattice Transformer. Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020, pp. 6836–6842.

- Liu, W.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, W. Lexicon Enhanced Chinese Sequence Labeling Using BERT Adapter. Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 5847–5858. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Che, W.; Liu, T.; Qin, B.; Yang, Z. Pre-Training With Whole Word Masking for Chinese BERT. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, 29, 3504–3514. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Association for Computing Machinery, 2016, KDD ’16, pp. 785–794. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Shi, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, H. Directional Skip-Gram: Explicitly Distinguishing Left and Right Context for Word Embeddings. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies(NAACL-HLT). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2018, pp. 175–180. [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Dredze, M. Improving Named Entity Recognition for Chinese Social Media with Word Segmentation Representation Learning. Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics(ACL). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2016, pp. 149–155. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Kit, C. Unsupervised Segmentation Helps Supervised Learning of Character Tagging for Word Segmentation and Named Entity Recognition. Proceedings of the Sixth SIGHAN Workshop on Chinese Language Processing, 2008.

- Lan, Z.; Chen, M.; Goodman, S.; Gimpel, K.; Sharma, P.; Soricut, R. ALBERT: A Lite BERT for Self-supervised Learning of Language Representations. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2019.

- Liu, X.y.; Li, Y.l.; Yin, B.; Tian, X. Chinese Address Understanding by Integrating Neural Network and Spatial Relationship. Science of Surveying and Mapping 2021, v.46;No.212, 165–171.

- Liu, X.; Hu, J.; Shen, Q.; Chen, H. Geo-BERT Pre-training Model for Query Rewriting in POI Search. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics(EMNLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021, pp. 2209–2214. [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Xie, Z.; Xu, D.; Jin, X.; Ma, K.; Tao, L.; Qiu, Q.; Pan, Y. Chinese Named Entity Recognition in the Geoscience Domain Based on BERT. Earth and Space Science 2022, 9, e2021EA002166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongwei, Z.; Qingyun, D.; Zhangjian, C.; Chen, Z. A Chinese Address Parsing Method Using RoBERTa-BiLSTM-CRF. Wuhan University Journal of Natural Sciences: Information Science Edition 2022.

| 1 | Pre-trained embeddings link: https://ai.tencent.com/ailab/nlp/en/data/tencent-ailab-embedding-en-d200-v0.1.0-s.tar.gz

|

| Configuration Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Framework | PyTorch |

| Python Version | 3.8.5 |

| PyTorch Version | 1.12.1+cu113 |

| Transformers Version | 4.33.2 |

| Experiment Device | Precision 3930 Rack Workstation |

| CPU | 3.3 GHz Intel(R) Xeon(R) E-2124 |

| GPU | NVIDIA RTX A4000 × 2 |

| Memory | 64GB |

| Operating System | 64-bit Windows 10 Professional Workstation |

| Parameter Name in English | Value | Parameter Name and Description in Chinese |

|---|---|---|

| Attention Heads | 4 | Number of attention heads: This refers to the number of heads in multi-head self-attention mechanisms, allowing the model to focus on different parts of input sequences at different positions, enhancing its ability to capture contextual information. |

| Batch Size | 32 | Batch size: The number of data samples used in each iteration to update the model weights. Larger batch sizes can accelerate training but may require more memory. |

| Dropout Ratio | 0.2 | Dropout rate: The probability of randomly dropping neurons during training, used to prevent overfitting and enhance model generalization capability. |

| Embedding Size d | 200 | Embedding dimension d: Dimensionality of embedding vectors used to represent input data, mapping discrete features into continuous vector spaces, commonly employed in natural language processing and recommendation systems. |

| Hidden State Size | 32 | Hidden state dimension : Dimension of hidden states in Transformer models, representing abstract representations of inputs at each position, influencing model representational capacity. |

| Learning Rate | 5e-5 | Learning rate: Controls the rate at which model parameters are updated during training, crucial for balancing training speed and performance, often requiring adjustment. |

| Max Seq Length | 128 | Maximum sequence length: Maximum allowable length of input sequences. Input sequences longer than this may need to be truncated or padded to fit the model. |

| Transformer Encoder Layers | 6 | Transformer encoder layers: Number of encoder layers in the Transformer model, determining model complexity and hierarchical performance. |

| Weight Decay | 0.01 | Weight decay: Regularization technique to mitigate model overfitting and improve generalization by penalizing large weights. |

| Warmup Ratio | 0.1 | Warmup ratio: Proportion of total training epochs dedicated to gradually increasing the learning rate, typically used to stabilize training in the initial phase. |

| Method | CADD | DOOR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | R | F | P | R | F | |

| Lattice-LSTM[14] (2018) | 89.47 | 89.11 | 89.29 | 90.55 | 90.19 | 90.37 |

| SoftLexicon-BERT [15] (2020) | 90.65 | 90.47 | 90.56 | 91.88 | 91.72 | 91.80 |

| ALBERT-BiGRU-CRF[26](2020) | 90.63 | 90.55 | 90.59 | 92.07 | 91.80 | 91.93 |

| BiGRU-CRF[27](2021) | 92.46 | 92.68 | 92.57 | 93.84 | 93.78 | 93.81 |

| LEBERT[20](2021) | 93.25 | 92.43 | 92.84 | 94.08 | 93.63 | 93.85 |

| GeoBERT[28] (2021) | 94.46 | 91.29 | 92.85 | 95.43 | 92.45 | 93.92 |

| BERT-BiGRU-CRF[29](2022) | 94.90 | 91.79 | 93.32 | 95.28 | 93.56 | 94.41 |

| BABERT[4] (2022) | 94.53 | 91.67 | 93.08 | 94.40 | 93.58 | 93.99 |

| RoBERTa-BiLSTM-CRF[30](2022) | 93.57 | 92.65 | 93.11 | 94.50 | 94.13 | 94.31 |

| MGeo[5] (2023) | 93.52 | 92.82 | 93.17 | 94.48 | 94.28 | 94.38 |

| ASSPM (Our) | 94.33 | 93.65 | 93.99 | 95.52 | 94.31 | 94.91 |

| Ablation method | Dateset | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CADD | DOOR | |||||

| P | R | F | P | R | F | |

| Baseline (ASSPM) | 94.33 | 93.65 | 93.99 | 95.52 | 94.31 | 94.91 |

| A-ESL w/o EBMSoftLexicon | 1.17↓ | 1.53↓ | 1.35↓ | 1.16↓ | 2.05↓ | 1.61↓ |

| A-SSLEBERT w/o SSLEBERT | 0.87↓ | 1.23↓ | 1.05↓ | 0.87↓ | 1.77↓ | 1.33↓ |

| A-S w/o S | 0.77↓ | 1.13↓ | 0.95↓ | 0.71↓ | 1.61↓ | 1.17↓ |

| A-BiGRU w/o BiGRU | 0.63↓ | 0.99↓ | 0.81↓ | 0.55↓ | 1.45↓ | 1.01↓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).