1. Introduction

Thermoelectric power plants that use coal combustion process to generate electricity produce solid by-products including boiler slag, bottom ash, flue gas desulphurization material and coal fly ash (CFA) (Heidrich, Feuerborn, & Weir, 2013). Amongst them, CFA is the one generated in large quantities and is disposed of in ash dams constructed in the vicinity of the power stations. Due to the much reliance in coal for power generation, the production of CFA is anticipated to reach more than 1 billion tons by 2030 as utilization rate does not counterbalance its production rate (Yadav et al., 2022). The utilization rate differs for countries, with highest reported in Denmark (100%), Italy (100%), Netherlands (100%), Japan (96.4%), France, Australia and Germany (85%), Canada (75%), and USA (65%) (Dwivedi, & Jain, 2014; Bhatt et al., 2019; Kelechi et al., 2022). The annual production of CFA in South Africa is around 26 million tons of which less than 10% is recycled and the remaining is stored in disposal sites converting large pieces of land to unusable sites (Van der Merwe et al., 2014). Two processes including the dry and wet method are used for CFA disposal, but they both have drawbacks. The dry disposal method involves the use of landfills and basins and this results to air pollution by fine CFA particles (Yu et al., 2013). In the wet disposal technique, CFA is dumped into ponds where it settles to the bottom and this method is linked to groundwater contamination due to leaching of pollutants (Qadir et al., 2019). These disposal methods are not environmentally-friendly and they are highly expensive to maintain. It is therefore imperative that other sustainable methods of managing CFA can be developed (Vilakazi et al., 2022).

CFA is largely characterized by metal oxides including SiO2, Al2O3, CaO, Fe2O3, MgO, Na2O, K2O, and these greatly influence its pH. The pH values of CFA can be categorized into three ranges; slightly alkaline (pH 6.5-7.5), moderately alkaline (pH 7.5-8.5) and highly alkaline (pH > 8) (Ivanova et al., 2011; Rashidi, & Yusup, 2016). The high concentration of soluble salts and pH values are unfavorable conditions for plant growth and as such CFA disposal sites are barren lands with no vegetation. Although some nutrients are available in CFA, it lacks phosphorus and nitrogen which are highly needed for plant growth. Furthermore, the toxicity of CFA has led to reduced number of microorganisms required to fix nitrogen and improve the fertility of the substrate (Gajić et al., 2018; Jambhulkar et al., 2018). Many reports have highlighted the presence of organic and inorganic pollutants in CFA. Trace metals and organic pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) have been reported in the CFA indicating its contribution to environmental pollution (Burgess et al., 2009). The particles of CFA are easily dispersed into the environment during windy seasons and as such can travel far distances resulting to air pollution. Toxic elements can leach into groundwaters and pollute waters resulting to soil, surface and groundwater pollution (Qadir et al., 2018). There are some conventional remediation methods to clean contaminated sites, specifically land contaminated with trace metals. In spite of being efficient, these methods are time consuming, environmentally devastating and expensive (Ahmadpour et al., 2012). Phytoremediation techniques are cost-effective, have long-term applicability and aesthetic advantages, hence they have been approved as suitable methods of cleaning up polluted areas and reducing pollutants from the soil (Jadia et al., 2009; Banda et al., 2021). Referring to Zgorelec et al. (2020), these techniques do not upset or damage the surrounding environment, nor do they require any additional energy input. The technology can provide a long-term plant cover which may reduce surface runoff and erosion, as well as minimizing the availability and mobility of trace metals in the environment therefore preventing their transfer to subsequent links of the food web and the migration of toxic ions to groundwater (Li, & Huang, 2015; Gajić et al., 2018; Zgorelec et al., 2020). Phytostabilization and phytoextraction are the two most used phytoremediation techniques and their difference in the mechanism is that phytostabilization method is able to immobilize the pollutants in the root system, while in phytoextraction process pollutants are translocated into the shoot systems (Ghosh et al., 2005; Nwoko, 2010; Eltaher et al., 2019; Zgorelec et al., 2020). When treating soil contaminated with trace metals such as Zn, and Cd using Zea mays L., phytostabilization has proven to be more effective than other techniques (Bakshe, & Jugade, 2023). Plants with a rapid growth rate, high biomass and high tolerance to toxic metals are the ideal candidates for phytoextraction, as they can transfer metals to the harvestable plant parts (Ali et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2020). The phytoremediation potential of plants species can be evaluated by determining their translocation factor (TF) and bioconcentration factor (BCF) (Maiti, Ghosh, & Raj, 2022). The BCF is an index of the capacity of the plant to accumulate metals into its roots with respect to its concentration in environmental matrix (Zhang et al., 2002; Ghosh, & Singh, 2005; Jambhulkar, & Juwarkar, 2009; Ahmadpour et al., 2012). A plant with a BCF value greater than 1 is considered as a good candidate for phytostabilization (Zhang et al., 2002; Yoon et al., 2006). TF indicates the ability of the plant to translocate metals from the roots to its aerial parts, and values above 1 indicates potential for phytoextraction (Ahmadpour et al., 2012; Hosman et al., 2017; Gajić et al., 2018; Banda et al., 2021). The practical application of phytoremediation process considers the use of plant species that do not require high maintenance and can grow and survive for longer periods. Despite the potential of the Helichrysum genus for phytoremediation processes, only a few plants from this family have received attention (Brunetti et al., 2017; Fernández et al., 2017; Banda et al., 2021). Species including Helichrysum italicum, Helichrysum candolleanum, Helichrysum decumbens, and Helichrysum splendidum have demonstrated potential for phytoremediation of contaminated soils, but no work has been reported for restoration of CFA deposits using Helichrysum splendidum. Helichrysum splendidum is a perennial plant that can grow effortlessly in adverse conditions such as hot weather conditions, wetlands, and in soils polluted with toxic metals, and therefore is an ideal candidate to remediate South African sites polluted with CFA.

2. Methodology

2.1. Sampling Site and Physicochemical Analysis

CFA sample was collected from Eskom, Hendrina power station located in Mpumalanga Province (26°2′S 29°36′E). Soil sample was also collected from a distant non-contaminated site in the same area to be used as control. Portions of the samples were air-dried and stored in glass bottles for further analysis. The pH and electrical conductivity (EC) of the samples were determined by weighing 5 g of each sample, transferred to a 50 mL centrifuge vial and 10 mL of deionized water was accurately measured and added to the sample. The mixture was placed on Labcon platform shaker (Laboratory Marketing Services CC, Maraisburg, South Africa) at 200 rpm for 12 hours and then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 5000 rpm. A pH/conductivity combimeter (Orion Star Series Meter Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., Beverly, USA) was used to measure the pH and EC of samples. The Walkley and Black method (chromic acid titration) was used to determine the total organic carbon (TOC) content of samples, where 0.16 M of potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) standard, 0.50 M ferrous sulphate heptahydrate (FeSO4.7H2O) solution and 0.025 M of ortho-phenanthroline indicator were prepared (Schumacher, 2002). 0.50 g of the soil or CFA were weighed and transferred to a 250 mL in a canonical flask and 10 mL of the K2Cr2O7 was added to the samples, followed by the addition of 20 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid and the mixture was left to stand for 30 minutes in the fume hood. 200 mL of deionized water was added to the mixture after 30 minutes and 10 drops of ortho-phenanthroline indicator was added and the solution was titrated using the FeSO4.7H2O solution.

2.2. Monitoring of Plant Growth

Helichrysum splendidum plants of almost same age purchased from Random Harvest Nursery (South Africa) were transplanted into 15 CFA and 3 control soil pots and these were used for metal uptake and translocation studies. The plants were watered thrice a week using tap water during the experiment. Using a measuring tape, the lengths of the longest stem from the root-stem junction to the leaf apex were measured every three weeks for a period of fourteen weeks to track the plant growth.

2.2.1. Harvesting

Following a fourteen-week period during which the pot trials were conducted, each entire plant was uprooted from the pot and thoroughly cleaned up with tap water to eliminate any remaining soil or CFA then rinsed with 2% HNO3 and finally with distilled water. Plants were separated into roots and shoots, and allowed to air dry. Once dried, the plants were milled using a ball miller (BM500, Anton Paar) at 15 Hz for 15 minutes and sieved (< 2 mm) to a homogenous sample and stored at room temperature until further use. The soil and CFA samples from the pots after harvest were also collected in plastic centrifuge vials and allowed to air dry for further analysis.

2.2.2. Sample Preparation Prior to Metal Analysis

Acid digestion was performed on control soil and CFA samples (before and after experiment), certified reference materials (CRMs) and plant parts in order to conduct a full elemental analysis on an inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Method validation was conducted using the CRM (SRM 1944, New York Waterway Sediments, NIST, New York, USA). CRM, control soil, shoots, roots, and CFA samples were accurately weighed (0. 25 g) and transferred into a conical flask and 5 mL of 65% HNO3 w/w was measured and poured in the conical flask. The mixture was placed on a hot plate at 110o C for 30 minutes and the resulting digests were diluted with 25 mL of deionized water. The mixture was then filtered using a micro-filter and stored in centrifuge vials. The samples were further diluted to 10 mL by measuring 100 µL and 9.9 mL of deionized water. ICP-MS was used for the analysis and determination of metal concentrations in the CFA and soil before and after experiment as well as in CRMs and plant materials. The calibration of the instrument was done using standards prepared from a 1000 mg. L-1 multi-elemental standard stock solution (Fluka A.G., Switzerland). The 1 mg. L-1 stock solution was prepared by measuring 0.05 mL of the multi-elemental stock solution, transferring it into a 250 mL volumetric flask and filling up to the mark using deionized water. From the stock solution (1 mg. L-1), 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 g. L-1 standard solutions were prepared. The instrument operating parameters were set as follows: nebulizer flow rate (0.88 L. min-1), ICP RF power (1500 W), auxiliary gas flow rate (1.2 L. min-1), plasma gas flow (18 L. min-1), and sample uptake rate (1.6 ml. min-1).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. CFA and Control Soil Characterizations before and After Experiment

The physical and chemical parameters of control soil and CFA collected from Hendrina power station (namely Dam 3B) before and after pot trials are presented in

Table 1. The parameters including EC, pH, and TOC were measured and they were significant in all media. The pH of control soil increased from 5.77 to 6.51 while for CFA decreased after 14 weeks of treatment. The pH of CFA decreased from 7.92 to 7.47, which indicate improved properties, as plants thrive in pH range that are slightly acidic to neutral. The reduced pH may be attributed to the organic acids produced by root exudates releasing the H

+ ion and therefore improving the CFA physicochemical properties. The recorded values suggest improved properties, supports microbial activity and results to nutrient availability.

The EC values of all the samples were increased, with control soils increasing from m 86.0 to 171.1±18.2 µS. cm-1, while the EC values of CFA increased from 152.0 to 380.3±42.1 µS. cm-1. This can be explained by the increased dissolution of minerals due to lower pH values suggesting improved bioavailability of these ions. The CFA is highly characterised by minerals and as such higher EC values were reported in CFA in comparison to soil samples. The EC of the substrate affects the transport of nutrients, as well as the uptake of water to the plants. The TOC of all the samples ranged between 2.58-3.92% which is an optimum amount supporting microorganisms, contributing to nutrient retention and improved structure of the substrate. The most desired TOC is in the range of 2-5% (Cheng et al., 2020), because high TOC percentages can restrict the mobility of metals. The values of pH and EC are related to plant growth and therefore, suggesting improved CFA conditions that are beneficial to plant development.

3.2. Plant Growth in the Control Soil and CFA during Pot Trials

After 14 weeks of the experiment, plant growth was measured and recorded, and a significant difference was observed for the control and CFA plants as depicted in

Table 2. The control plant growth was increased by 18.9%, while the CFA plants reported 10.0% growth. These indicated phytotoxicity which can be attributed to the presence of pollutants such as toxic metals in CFA and lower microbial activity that supports plant growth (Chen et al., 2024). As it is seen in

Table 2, the plants in the CFA were stunted as compared to those in the control soil.

3.3. Gas Exchange Analysis

Gas exchange measurements are conducted to evaluate physiological properties of the plant, including CO

2 assimilation or photosynthetic rate (A), transpiration efficiency (E), stomatal conductance to water vapor (Gs) and intercellular CO

2 (Ci) on a leaf. From the data obtained for Gs and Ci, the water use efficiency of the plant can be determined. The gas exchange measurement was done on plants grown in five treatments assigned soil-S

1, soil-S

2, which were the controls and three CFA samples, assigned CFA-C

1, CFA-C

2 and CFA-C

3, which were CFAs. The values of A which indicate the CO

2 assimilation were higher for the controls, and slightly lower values were observed for the CFA plants, with lowest values found in CFA-C

3 plants. This is in correlation with the plant growth which was slightly lower for the CFA plants. The results revealed that there were no significant differences in the values of Gs, Ci and E for both the controls and the CFA plants. The WUE was calculated by dividing A with Gs and the results revealed no significant difference for both the controls and the CFA plants. Intercellular CO

2 which determines the flux of carbon dioxide into the leaf if the stomata opening remain constant, as the closure of the stomata can lead to uncertainties. The results reveled no significant differences which suggest that, plants grown in CFA had accumulated significant biomass under harsh conditions of the CFA. the concentration in the controls were found to be 259.1±6.3 µmol (CO

2) mol

-1air

-1 for the CAF and 258.20±6.57µmol (CO

2) mol

-1air

-1 was reported for the controls (

Table 3). Plant grown in soil had higher WUE values than CFA plants, indicating that more water is necessary for the CFA plants, hence the watering schedule for the CFA plants was slightly altered. The variation in photosynthetic characteristics can be due to the restricted movement of water, therefore restricting the supply of nutrients availability of nutrients (Makoi et al., 2010; Hatfield, & Dold, 2019).

3.3. Metal Analysis

ICP-MS was used to measure the concentrations of As, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mn, Ni, Pb and Zn in CFA and control soil (before and after treatment), roots and shoots of

H. splendidum in order to assess their uptake, accumulation and translocation (

Table 4 and

Table 5). The baseline concentration of CFA and soil samples were determined in order to evaluate the removal efficiency of the elements from the substrates. The method validation was conducted by determining these elements in the CRM (SRM 1944, New York Waterway Sediments, National Institute of Standards and Technology, New York, USA) and the results were within the certified values as presented in

Table 4.

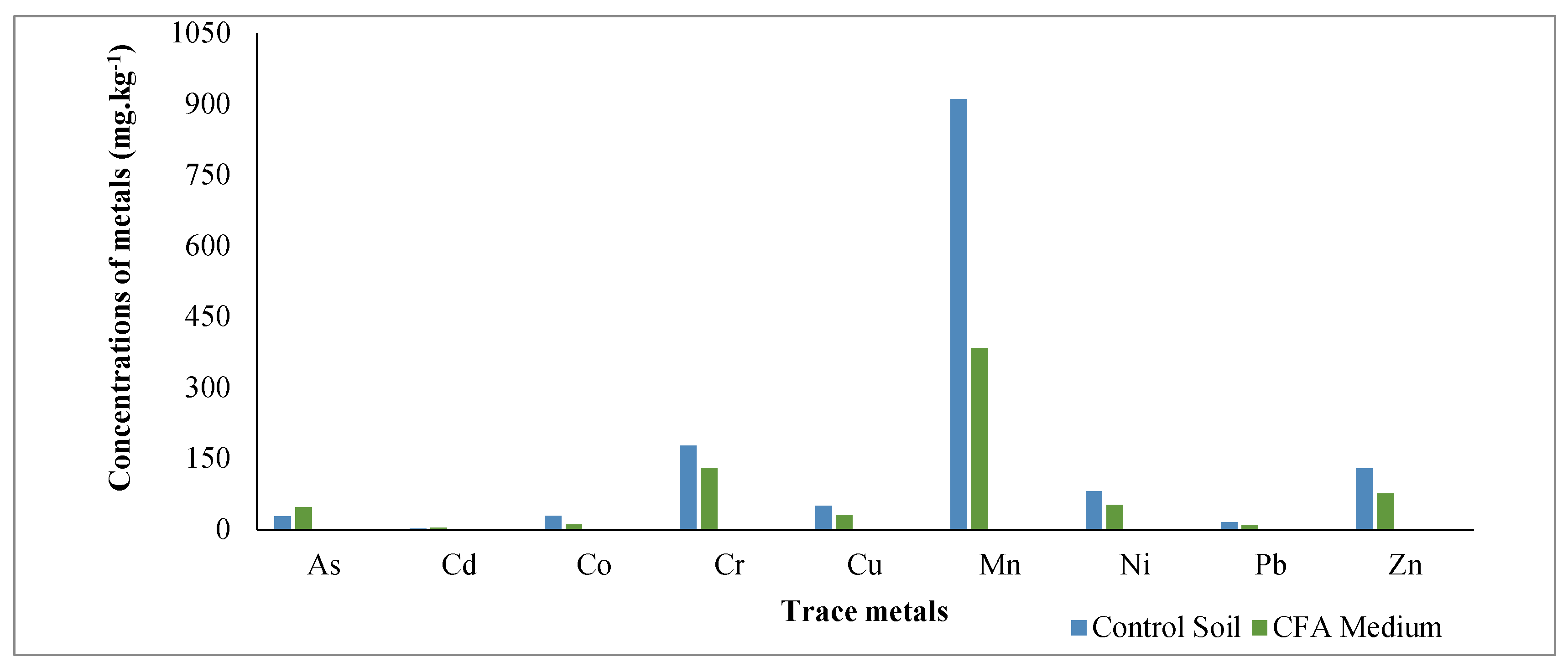

The results revealed that CFA and the control soil media contained all the tested elements and their pattern was Mn > Cr > Zn> Ni > As > Cu > Co > Pb > Cd in CFA and Mn > Cr > Zn> Ni > Cu > Co > As > Pb > Cd in Control soil as shown in

Figure 1 and

Table 5.

The control soil medium has higher concentrations of these elements as compared to the CFA except As and Cd (

Figure 1). The amount of As and Cr in CFA were found to be 47.2±4.1 and 131.0±14.9 mg.kg

-1, which exceeded the permissible limit of Earth’s crust average concentrations (1.7 and 83 mg.kg

-1 for As and Cr, respectively), indicating that CFA is polluted with these toxic metals (Altıkulaç, et al., 2022). The concentration of Mn (384.0±23.1 mg. kg

-1) was the highest amongst the measured elements in CFA and Cd was the lowest (4.5±0.3 mg.kg

-1). As illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Table 5, a significant reduction of metal concentrations was recorded for all elements with highest removal efficiency found for As, Cu, Ni and Zn. The removal efficiency of metals from CFA ranged between 15.80 and 56.70%, indicating that

H. splendidum ability to assimilate toxic elements into its tissues differ from one element to the other. The highest removal efficiency was observed for As (48%), Cu (56.7%) and Zn (55.6%) suggesting that the plant is more effective in removing these elements and this is not linked to the amount of the element in the original substrate. Although Mn was initially high in CFA (456.00±36.2 mg.kg

-1), the removal efficiency of this element was 15.8%, indicating a restricted movement of this metal. The concentrations of Pb was found to be moderate in CFA (9.70±1.3 mg.kg

-1), and the highest amount was found in the roots (5.60±0.3 mg.kg

-1) as compared to the shoots (4.20±0.06 mg.kg

-1. Similarly, lower amount was found in the roots of

H. splendidum for the controls and this can suggest that mobility is restricted in the substrates with lower Pb amounts. The removal efficiency for Pb was 21.8% indicating that, Pb can be removed from CFA with the use of

H. splendidum.

The study revealed that

H. splendidum can take up metals and assimilate them into its tissues (roots and shoots) as presented in

Table 5 and

Figure 2 (A and B). Most of the elements were accumulated in the roots as compared to the shoots for both the control soil and the CFA grown plants. Higher concentrations of Cd, Co, Cd, Cu, Mn and Pb were found in the roots, while the shoots had higher amount of As, Cr and Zn for the control soil grown plants as shown in

Figure 2 (A and B). In contrast, Cr was mostly accumulated in the roots of CFA grown plants, while As and Zn were mostly accumulated in the shoots of CFA grown plants. The concentration of Cr was found to be 69.8±3.8 mg.kg

-1 in the shoots and 100±7.7 mg.kg

-1 in the roots. The concentration of Ni was not significantly different between the shoots and the roots, reporting 45.9±5.81 mg.kg

-1 in the shoots, while 42.4±3.04 mg.kg

-1 found in the roots.

Another observation was that plant tissues in the control soil medium highly accumulated and translocated these metals than the ones in the CFA medium. This can be explained by enough plant biomass in the control soil medium enhancing the accumulation and translocation of these metals in the roots and shoots, respectively.

3.4. Assessing the Potential of Helichrsyum Splendidum for Phytoremediation of CFA-Polluted Sites

In this study, phytoextraction and phytostabilization processes were performed on

Helichrsyum splendidum species planted in both control soil and CFA media. To estimate a phytoremediation potential of a plant, translocation factors (TFs) and bioconcentration factors (BCFs) are widely applied (Yoon et al., 2006; Maiti, Ghosh, & Raj, 2022). Metal uptake and bioaccumulation in plant species can vary from metal to metal and species to species. Translocation of elements from the roots to the shoots is the measure used to evaluate phytoextraction, whereas in the phytostabilzation process, the metals are accumulated in the roots of the plant (Chowdhury, & Maiti, 2016). BCF values of As, Cu and Zn in CFA and As and Zn in the control soil media were greater than 1 as depicted in

Table 5. The rest BCFs of Pb, Mn, Co, Ni, Cd, and Cr in CFA medium and BCFs of Pb, Mn, Ni, Co, Cu, and Cd in control soil medium were less than 1. TFs Pb, Mn, Co, Cu, Cd, and Cr in control soil medium and TFs of Pb, Mn, Co, Cu, Cd, and Cr in CFA grown plants were also less than 1. TFs of Ni, Zn and As in CFA and As, Cr and Zn in control soil grown plants were greater than 1 while TFs of Pb, Mn, Co, Cu, Cd, and Cr in CFA grown plants and TFs of Cd, Co, Cu, Mn, Ni, and Pb in the control soil grown plants were less than 1. However, all these metals with TFs<1 were accumulated in the roots and not translocated to the leaves except Ni, As and Zn in the CFA grown plants.

In summary, the metal concentrations in the CFA grown plants were almost comparable with those in the control soil grown plants, importantly the Cr, Zn and Mn concentrations were greater in the shoots for control soil grown plants compared to the CFA grown plants. Mn presented a high concertation in the roots in both medium grown plants. Banda et al. (2021) reported that Helichrysum splendidum was able to grow, uptake and translocate metals in artificially Cu- and Pb-contaminated soil even at high concentration, this agrees with the results obtained in this study, which showed that Helichrysum splendidum was able to extract all metals from the substrates to its tissues rendering it to be good phytostabilizer and phytoextractor candidate for trace metals.

4. Conclusion

For many years, South Africa has relied on coal for power generation and a significant amount of CFA is stored in various open ash disposal sites, which represents serious environmental pollution issues. The study was able to highlight the potential of Helichrysum splendidum for phytoremediation of CFA-polluted sites in South Africa. The plants did not show high BCF and TFs values, but some were greater than 1 in CFA grown plants which make the plant species to be a good phytoextractor. The study showed an even distribution of metal contents in the soils and plant tissues and it also showed low TFs, which also makes the plant species an attractive potential for the phytostabilization of metal contents. Although CFA medium had restricted growth of some plants as compared to the controls, the results showed an interesting removal efficiency ranging between 18.0 to 56.7% with highest reported for Cu and Zn. From the obtained results, it can be concluded that Helichrysum splendidum has the potential to be used for plant-based remediation of CFA-polluted site. The technique can be used to reduce the concentrations of trace metals from the CFA and it can become less toxic and suitable for plantation. The performed gas exchange parameters were very similar in both control soil and in CFA media. Further studies of Helichrysum splendidum for different CFA treatments need to be conducted to enhance the plant phytoremediation capabilities.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank the Tshwane University of Technology for supporting this project and the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant no. 129752) for funding.

References

- Ahmadpour, P.; Ahmadpour, F.; Maumud, T.M.M.; Arifin, A.; Soleimani, M.; Hosseini Tayefe, F. Phytoremediation of heavy metals: A green technology. African Journal of Biotechnology 2012, 11, 14036–14043. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Sajad, M.A. Phytoremediation of heavy metals—Concepts and applications. Chemosphere: Environmental Chemistry 2013, 91, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshe, P.; Jugade, R. Phytostabilization and rhizofiltration of toxic heavy metals by heavy metal accumulator plants for sustainable management of contaminated industrial sites: A comprehensive review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2023, 10, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, M.; Mokgalaka, N.; Combrinck, S.; Regnier, T. Five-weeks pot trial evaluation of phytoremediation potential of Helichrysum splendidum Less. for copper- and lead-contaminated soils. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 19, 1837–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.; Priyadarshini, S.; Mohanakrishnan, A.A.; Abri, A.; Sattler, M.; Techapaphawit, S. Physical, chemical, and geotechnical properties of coal fly ash: A global review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2019, 11, e00263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, G.; Ruta, C.; Traversa, A.; D'Ambruoso, G.; Tarraf, W.; De Mastro, F.; De Mastro, G.; Cocozza, C. Remediation of a heavy metals contaminated soil using mycorrhized and non-mycorrhizedHelichrysum italicum(Roth) Don. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R.M.; Perron, M.M.; Friedman, C.L.; Suuberg, E.M.; Pennell, K.G.; Cantwell, M.G.; Pelletier, M.C.; Ho, K.T.; Serbst, J.R.; Ryba, S.A. Evaluation of the effects of coal fly ash amendments on the toxicity of a contaminated marine sediment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 28, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Fan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liao, X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, T. A comprehensive review of toxicity of coal fly ash and its leachate in the ecosystem. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 269, 115905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Gao, X.; Cao, L.; Wang, Q.; Qiao, Y. Quantification of Total Organic Carbon in Ashes from Smoldering Combustion of Sewage Sludge via a Thermal Treatment—TGA Method. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 33445–33454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Maiti, S.K. Assessing the ecological health risk in a conserved mangrove ecosystem due to heavy metal pollution: A case study from Sundarbans Biosphere Reserve, India. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assessment: Int. J. 2016, 22, 1519–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Jain, M.K. Fly ash-waste management and overview: A Review. Recent Research in Science and Technology, 2014; 6, http://recent-science.com/index.php/rrst/article/view/18691/9414. [Google Scholar]

- Eltaher, G.; Ahmed, D.; El-Beheiry, M.; El-Din, A.S. Biomass estimation and heavy metal accumulation by Pluchea dioscoridis (L.) DC. in the Middle Nile Delta, (Egypt): Perspectives for phytoremediation. South Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 127, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, S.; Poschenrieder, C.; Marcenò, C.; Gallego, J.; Jiménez-Gámez, D.; Bueno, A.; Afif, E. Phytoremediation capability of native plant species living on Pb-Zn and Hg-As mining wastes in the Cantabrian range, north of Spain. J. Geochem. Explor. 2017, 174, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, G.; Djurdjević, L.; Kostić, O.; Jarić, S.; Mitrović, M.; Pavlović, P. Ecological Potential of Plants for Phytoremediation and Ecorestoration of Fly Ash Deposits and Mine Wastes. Front. Environ. Sci. 2018, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Singh, S.P. A Review on Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals and Utilization of its by-products. Asian Journal on Energy and Environment 2005, 6, 214–231. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.K.; Sinha, S. Decontamination and/or revegetation of fly ash dykes through naturally growing plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 153, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Dold, C. Water-Use Efficiency: Advances and Challenges in a Changing Climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 429990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidrich, C. , Feuerborn, H. J., & Weir, A. (2013). Coal combustion products: a global perspective. In World of coal ash conference (pp. 22-25). https://www.gypsum.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/VGBPowerTech2013-12pp46-52HEIDRICHAutorenexemplar.pdf.

- Ivanova, T. S. , Panov, Z., Blazev, K. and Paneva, V. Z. (2011). Investigation of Fly Ash Heavy Metals Content and Physico-chemical Properties from Thermal Power Plant, Republic of Macedonia. International Journal of Engineering Science and Technology. 3(12). Pg 8219-8225. https://eprints.ugd.edu.mk/3573/1/IJEST11-03-12-194.pdf.

- Jadia, C.D.; Fulekar, M.H. Phytoremediation of heavy metals: Recent techniques. African Journal of Biotechnology 2009, 8, 921–928. [Google Scholar]

- Jambhulkar, H.P.; Juwarkar, A.A. Assessment of bioaccumulation of heavy metals by different plant species grown on fly ash dump. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2009, 72, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambhulkar, H.P.; Shaikh, S.M.S.; Kumar, M.S. Fly ash toxicity, emerging issues and possible implications for its exploitation in agriculture; Indian scenario: A review. Chemosphere 2018, 213, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelechi, S.E.; Adamu, M.; Uche, O.A.U.; Okokpujie, I.P.; Ibrahim, Y.E.; Obianyo, I.I. A comprehensive review on coal fly ash and its application in the construction industry. Cogent Eng. 2022, 9, 2114201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, L. Toward a New Paradigm for Tailings Phytostabilization—Nature of the Substrates, Amendment Options, and Anthropogenic Pedogenesis. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 813–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoi, J.H.J.R.; Chimphango, S.B.M.; Dakora, F.D. Photosynthesis, water-use efficiency and δ13C of five cowpea genotypes grown in mixed culture and at different densities with sorghum. Photosynthetica 2010, 48, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, S. K. , Ghosh, D., & Raj, D. (2022). Phytoremediation of fly ash: bioaccumulation and translocation of metals in natural colonizing vegetation on fly ash lagoons. Handbook of Fly Ash, 501-523. [CrossRef]

- Nwoko, C. O. (2010). Trends in phytoremediation of toxic elemental and organic pollutants. African Journal of Biotechnology, 9(37), 6010-6016. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajb/article/view/92167.

- Schumacher, B. A. (2002). Methods for the determination of total organic carbon (TOC) in soils and sediments (pp. 1-23). Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, Ecological Risk Assessment Support Centre.

- van der Merwe, E.; Prinsloo, L.; Mathebula, C.; Swart, H.; Coetsee, E.; Doucet, F. Surface and bulk characterization of an ultrafine South African coal fly ash with reference to polymer applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 317, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, S.U.; Raja, V.; Siddiqui, W.A.; Mahmooduzzafar; Abd_Allah, E. F.; Hashem, A.; Alam, P.; Ahmad, P. Fly-Ash Pollution Modulates Growth, Biochemical Attributes, Antioxidant Activity and Gene Expression in Pithecellobium Dulce (Roxb) Benth. Plants 2019, 8, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramagoma, M. J. (2018). Coal fly ash waste management challenges in the South African power generation sector and possible recycling opportunities: A case study of Hendrina and Kendal power stations. (MSc Dissertation, University of Witwatersrand).

- Rashidi, N.A.; Yusup, S. Overview on the Potential of Coal-Based Bottom Ash as Low-Cost Adsorbents. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 1870–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilakazi, A.Q.; Ndlovu, S.; Liberty Chipise; Shemi, A. The Recycling of Coal Fly Ash: A Review on Sustainable Developments and Economic Considerations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.K.; Gacem, A.; Choudhary, N.; Rai, A.; Kumar, P.; Yadav, K.K.; Abbas, M.; Ben Khedher, N.; Awwad, N.S.; Barik, D.; et al. Status of Coal-Based Thermal Power Plants, Coal Fly Ash Production, Utilization in India and Their Emerging Applications. Minerals 2022, 12, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Cao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, L.Q. Accumulation of Pb, Cu, and Zn in native plants growing on a contaminated Florida site. Sci. Total. Environ. 2006, 368, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Sun, L.; Xiang, J.; Jin, L.; Hu, S.; Su, S.; Qiu, J. Physical and chemical characterization of ashes from a municipal solid waste incinerator in China. Waste Manag. Res. J. a Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2013, 31, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgorelec, Z.; Bilandzija, N.; Knez, K.; Galic, M.; Zuzul, S. Cadmium and Mercury phytostabilization from soil using Miscanthus × giganteus. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-63488-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cai, Y.; Tu, C.; Ma, L.Q. Arsenic speciation and distribution in an arsenic hyperaccumulating plant. Sci. Total. Environ. 2002, 300, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).