Submitted:

27 June 2024

Posted:

01 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

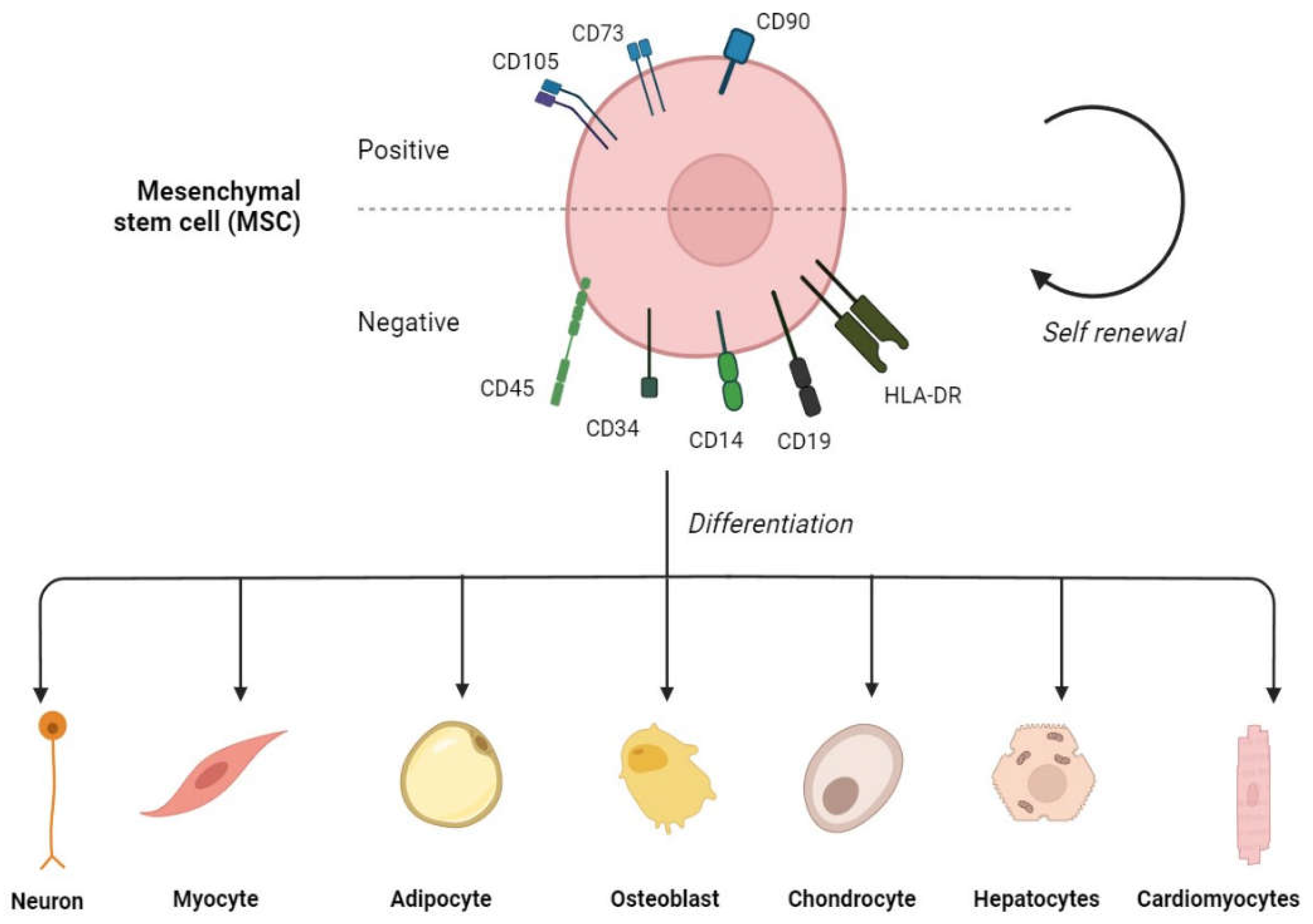

1. Introduction

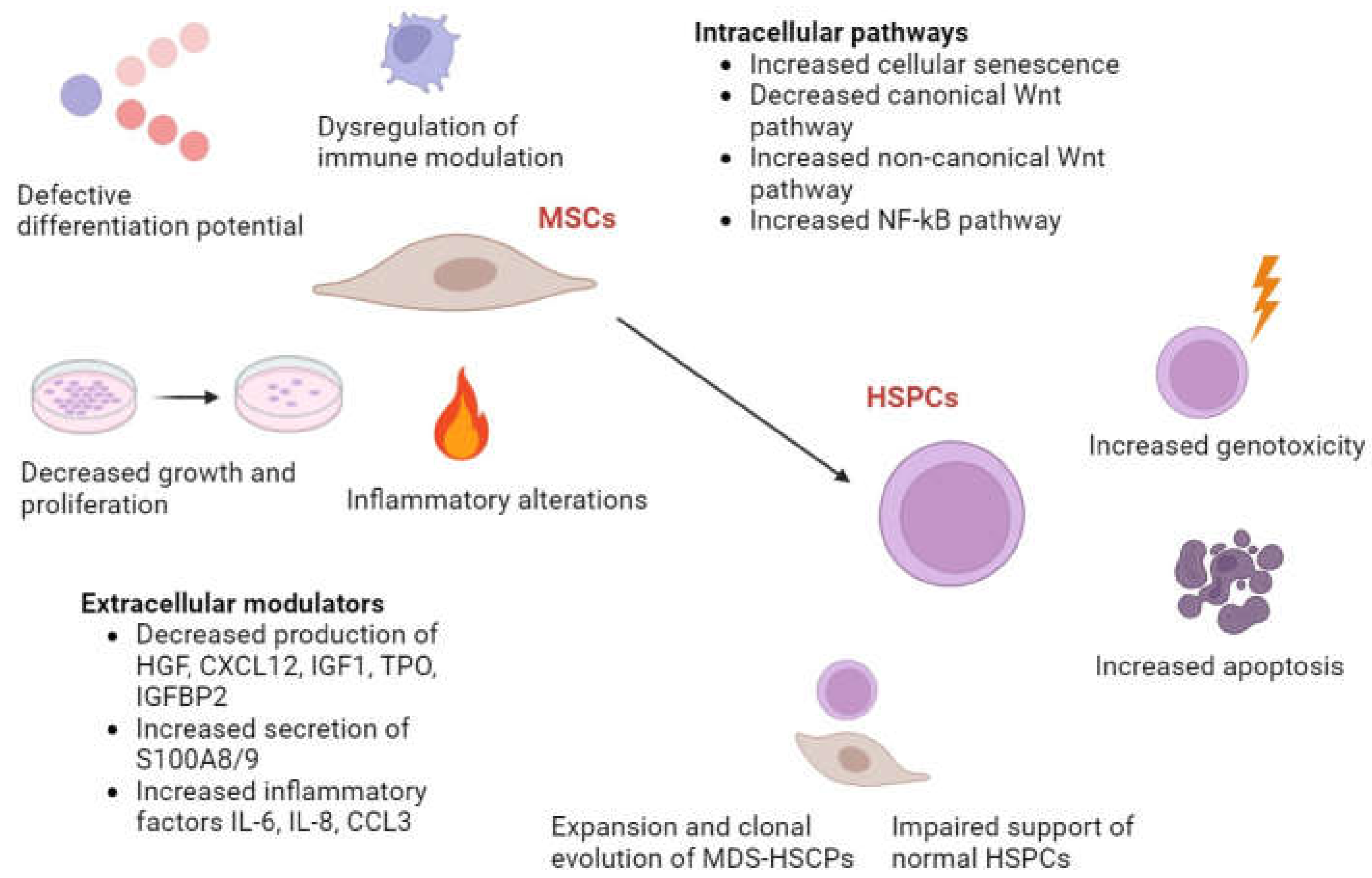

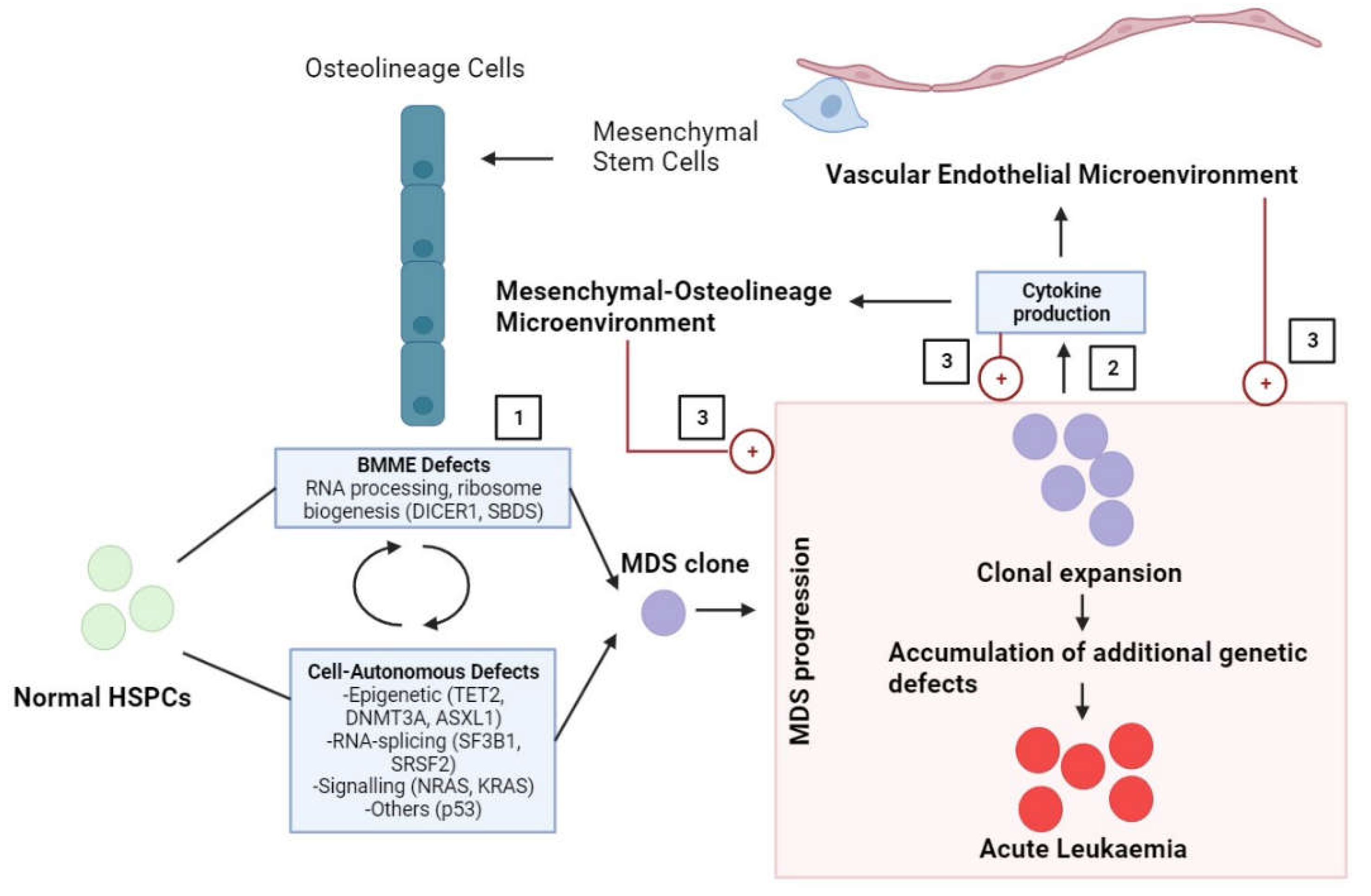

2. Role of MSCs in Pre-Leukaemia Myelodysplastic Pathogenesis

2.1. Impaired Morphology and Immunophenotype of MSCs in MDS

2.2. Cytogenetic and Genetic Abnormalities of MSCs in MDS

2.3. Abnormal Hematopoietic Microenvironment Induced by MSCs in MDS

2.4. Immunomodulatory Dysfunction by MSCs in MDS

2.5. Cytokine Dysregulation Mediated by MSCs in MDS

2.6. Altered Growth Kinetics and Elevated Cellular Senescence of MSCs in MDS

2.7. Reduced Osteogenic Differentiation Caused by MSCs in MDS

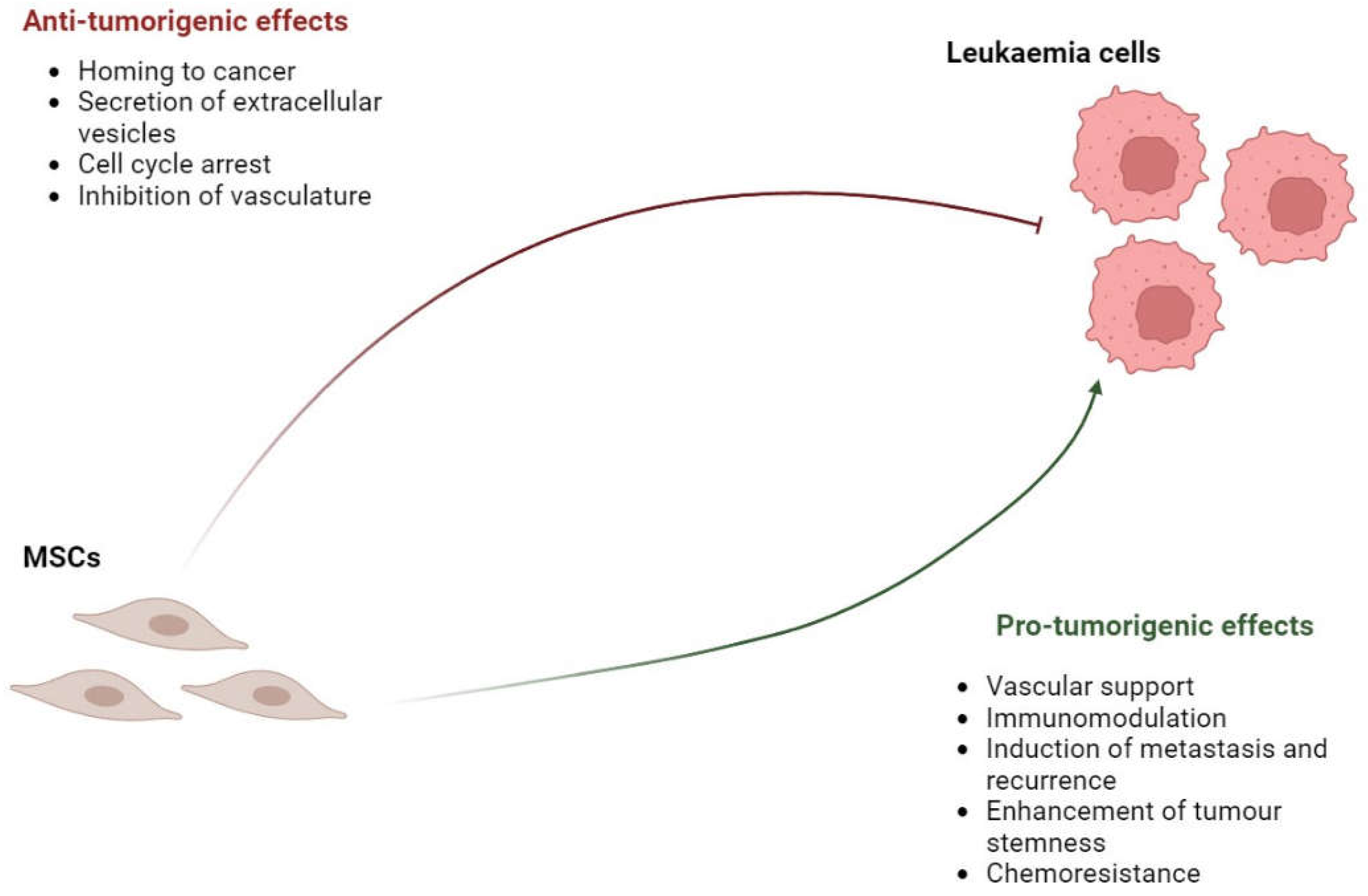

3. Role of MSCs in Leukaemia Pathogenesis

3.1. Pro-tumorigenic Effects of MSCs in Leukaemia

3.2. Anti-tumorigenic Effects of MSCs in leukaemia

3.3. Changes in MSCs in Leukaemia

4. Role of MSCs in Lymphoma and Multiple Myeloma Pathogenesis

5. Potential Use of MSCs in Therapies for Blood Cancers

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSCs Mesenchymal stem cells BM Bone marrow HSC Hematopoietic stem cells DCs Dendritic cells NKs Natural killer cells TGF-β Transforming growth factor beta EGF Epidermal growth factor GM-CSF Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor ALCAM Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule ICAM-1 Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 IL Interleukin PGE2 Prostaglandin E2 HLA-G Human leukocyte antigen ECM Extracellular matrix MDS Myelodysplastic syndromes FAB French-American-British RA Refractory anaemia RARS Refractory anaemia with ringed sideroblasts RAEB Refractory anaemia with excess blasts RAEB-T Refractory anaemia with excess blasts in transformation CMML Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia WHO World Health Organisation RCUD Refractory cytopenia with unilineage dysplasia RCMD Refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia MDS-U MDS, unclassified MDS-SLD MDS with single lineage dysplasia MDS-MLD MDS with multilineage dysplasia MDS-RS MDS with ring sideroblasts MDS-RS-SLD MDS-RS with single-lineage dysplasia MDS-RS-MLD MDS-RS with multi-lineage dysplasia MDS-EB MDS with excess blasts RCC Refractory cytopenia in childhood MDS-LB MDS with low blasts MDS-h MDS hypoplastic MDS-IB MDS with increased blasts IPSS International Prognostic Scoring System BMSC Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells AML acute myeloid leukaemia HSPC Hemaetopoietic stem and progenitor cells NF- κB Nuclear factor kappa B TNF Tumour necrosis factor ANGPT Angiopoietin HGF Hepatocyte growth factor CXCL12 C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 TPO Thrombopoietin IGFBP2 Insulin growth factor binding protein 2 |

CCL3 C-C motif chemokine ligand LR-MDS Low risk-MDS HR-MDS High risk-MDS BMME Bone marrow microenvironment IFN-γ Interferon-gamma SCF Stem cell factor IGF1 Insulin-like growth factor 1 HPC Haematopoietic progenitor cells TBX15 T-Box transcription factor 15 PITX2 Paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 2 HOXB1 Homeobox B1 mRNA Messenger ribonucleic acid OC Osteocalcin ALP Alkaline phosphatases FABP4 Fatty acid-binding protein 4 AML Acute myeloid leukaemia CML Chronic myeloid leukaemia ALL Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia CLL Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia VEGF Vascular endothelial factor FGF Fibroblast growth factor PDGF Platelet-derived growth factor COX-2 Cyclooxygenase 2 CCL2 C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 CAFs Cancer-associated fibroblasts hUC-MSCs Human umbilical cord-derived MSCs DKK1 Dickkopf-related protein 1 GVHD Graft-versus-host disease CINC-1 Cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-1 TIMP-1 Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 B-ALL B-acute lymphoblastic leukaemia HD Hodgkin disease NHL Non-Hodgkin lymphoma MCP-1 Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 IDO Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase EVs Extracellular vesicles MM-MSCs Multiple myeloma MSCs G-MDSCs Granulocytic-myeloid-derived suppressor cells TME Tumour microenvironment MCL Mantle Cell Lymphoma DLBCL Diffuse Large B-cell lymphoma HA Hypomethylating agents AZA Azacitidine CDKN1A Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A ALA α-lipoic acid ROS Reactive oxygen species Ems Exosome mimetics |

References

- Viswanathan, S.; Shi, Y.; Galipeau, J.; Krampera, M.; Leblanc, K.; Martin, I.; Nolta, J.; Phinney, D.G.; Sensebe, L. Mesenchymal stem versus stromal cells: International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT®) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell committee position statement on nomenclature. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Liu, N.; Bao, C.-M.; Yang, D.-Z.; Ma, G.-X.; Yi, W.-H.; Xiao, G.-Z.; Cao, H.-L. Mesenchymal stem cells in fibrotic diseases-the two sides of the same coin. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petite, H.; Viateau, V.; Bensaïd, W.; Meunier, A.; Pollak, C. de; Bourguignon, M.; Oudina, K.; Sedel, L.; Guillemin, G. Tissue-engineered bone regeneration. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000, 18, 959–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajwal, G.S.; Jeyaraman, N.; Kanth V, K.; Jeyaraman, M.; Muthu, S.; Rajendran, S.N.S.; Rajendran, R.L.; Khanna, M.; Oh, E.J.; Choi, K.Y.; et al. Lineage Differentiation Potential of Different Sources of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Osteoarthritis Knee. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cominal, J.G.; Da Costa Cacemiro, M.; Pinto-Simões, B.; Kolb, H.-J.; Malmegrim, K.C.R.; Castro, F.A. de. Emerging Role of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Pathogenesis of Haematological Malignancies. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 6854080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Wu, Y. Paracrine molecules of mesenchymal stem cells for hematopoietic stem cell niche. Bone Marrow Res. 2011, 2011, 353878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asari, S.; Itakura, S.; Ferreri, K.; Liu, C.-P.; Kuroda, Y.; Kandeel, F.; Mullen, Y. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress B-cell terminal differentiation. Exp. Hematol. 2009, 37, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronthos, S.; Franklin, D.M.; Leddy, H.A.; Robey, P.G.; Storms, R.W.; Gimble, J.M. Surface protein characterization of human adipose tissue-derived stromal cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2001, 189, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiret, N.; Rapatel, C.; Veyrat-Masson, R.; Guillouard, L.; Guérin, J.-J.; Pigeon, P.; Descamps, S.; Boisgard, S.; Berger, M.G. Characterization of nonexpanded mesenchymal progenitor cells from normal adult human bone marrow. Exp. Hematol. 2005, 33, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dazzi, F.; Ramasamy, R.; Glennie, S.; Jones, S.P.; Roberts, I. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in haemopoiesis. Blood Rev. 2006, 20, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnecchi, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, A.; Dzau, V.J. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ. Res. 2008, 103, 1204–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.-R.; Zhang, Q.-Z.; Shi, S.-H.; Nguyen, A.L.; Le, A.D. Human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stromal cells attenuate contact hypersensitivity via prostaglandin E2-dependent mechanisms. Stem Cells 2011, 29, 1849–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, S.; Patel, S.A.; Kartan, S.; Axelrod, D.; Capitle, E.; Rameshwar, P. Tolerance-like mediated suppression by mesenchymal stem cells in patients with dust mite allergy-induced asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augello, A.; Tasso, R.; Negrini, S.M.; Cancedda, R.; Pennesi, G. Cell therapy using allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells prevents tissue damage in collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Xu, C.; Asada, N.; Frenette, P.S. The hematopoietic stem cell niche: from embryo to adult. Development 2018, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batsali, A.K.; Georgopoulou, A.; Mavroudi, I.; Matheakakis, A.; Pontikoglou, C.G.; Papadaki, H.A. The Role of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Derived Extracellular Vesicles (MSC-EVs) in Normal and Abnormal Hematopoiesis and Their Therapeutic Potential. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröbel, J.; Landspersky, T.; Percin, G.; Schreck, C.; Rahmig, S.; Ori, A.; Nowak, D.; Essers, M.; Waskow, C.; Oostendorp, R.A.J. The Hematopoietic Bone Marrow Niche Ecosystem. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 705410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, C.R.; Olsen, G.H.; Dworkin, S.; Fabb, S.A.; Swann, J.; McArthur, G.A.; Westmoreland, S.V.; Chambon, P.; Scadden, D.T.; Purton, L.E. A microenvironment-induced myeloproliferative syndrome caused by retinoic acid receptor gamma deficiency. Cell 2007, 129, 1097–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Xie, Y.; Xu, J.-R.; Luo, Q.; Ren, Y.-X.; Chen, M.; Duan, J.-L.; Bao, C.-J.; Liu, Y.-X.; Li, P.-S.; et al. Engineered stem cell biomimetic liposomes carrying levamisole for macrophage immunity reconstruction in leukemia therapy. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 447, 137582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaemmanuil, E.; Cazzola, M.; Boultwood, J.; Malcovati, L.; Vyas, P.; Bowen, D.; Pellagatti, A.; Wainscoat, J.S.; Hellstrom-Lindberg, E.; Gambacorti-Passerini, C.; et al. Somatic SF3B1 mutation in myelodysplasia with ring sideroblasts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1384–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Sanada, M.; Shiraishi, Y.; Nowak, D.; Nagata, Y.; Yamamoto, R.; Sato, Y.; Sato-Otsubo, A.; Kon, A.; Nagasaki, M.; et al. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature 2011, 478, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mian, S.A.; Smith, A.E.; Kulasekararaj, A.G.; Kizilors, A.; Mohamedali, A.M.; Lea, N.C.; Mitsopoulos, K.; Ford, K.; Nasser, E.; Seidl, T.; et al. Spliceosome mutations exhibit specific associations with epigenetic modifiers and proto-oncogenes mutated in myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica 2013, 98, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasserjian, R.P.; Germing, U.; Malcovati, L. Diagnosis and classification of myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2023, 142, 2247–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, M.; He, G. The 2016 Revision to the World Health Organization Classification of Myelodysplastic Syndromes. J. Transl. Int. Med. 2017, 5, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, P.L.; Attar, E.; Bennett, J.M.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Borate, U.; Castro, C.M. de; Deeg, H.J.; Frankfurt, O.; Gaensler, K.; Garcia-Manero, G.; et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes: clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2013, 11, 838–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beachy, S.H.; Aplan, P.D. Mouse models of myelodysplastic syndromes. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2010, 24, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Li, M.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W.; Cao, L.; Gao, R. Summary of animal models of myelodysplastic syndrome. Animal Model. Exp. Med. 2021, 4, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papapetrou, E.P. Modeling myeloid malignancies with patient-derived iPSCs. Exp. Hematol. 2019, 71, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontikoglou, C.G.; Matheakakis, A.; Papadaki, H.A. The mesenchymal compartment in myelodysplastic syndrome: Its role in the pathogenesis of the disorder and its therapeutic targeting. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Villar, O.; Garcia, J.L.; Sanchez-Guijo, F.M.; Robledo, C.; Villaron, E.M.; Hernández-Campo, P.; Lopez-Holgado, N.; Diez-Campelo, M.; Barbado, M.V.; Perez-Simon, J.A.; et al. Both expanded and uncultured mesenchymal stem cells from MDS patients are genomically abnormal, showing a specific genetic profile for the 5q- syndrome. Leukemia 2009, 23, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Figueroa, E.; Arana-Trejo, R.M.; Gutiérrez-Espíndola, G.; Pérez-Cabrera, A.; Mayani, H. Mesenchymal stem cells in myelodysplastic syndromes: phenotypic and cytogenetic characterization. Leuk. Res. 2005, 29, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, G.; Kiss, J.; Várkonyi, J.; Vas, V.; Farkas, P.; Pálóczi, K.; Uher, F. Inappropriate Notch activity and limited mesenchymal stem cell plasticity in the bone marrow of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2007, 13, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Figueroa, E.; Montesinos, J.J.; Flores-Guzmán, P.; Gutiérrez-Espíndola, G.; Arana-Trejo, R.M.; Castillo-Medina, S.; Pérez-Cabrera, A.; Hernández-Estévez, E.; Arriaga, L.; Mayani, H. Functional analysis of myelodysplastic syndromes-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Leuk. Res. 2008, 32, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi-Gang, Z.; Wei-Ming, L.; Zhi-Chao, C.; Yong, Y.; Ping, Z. Immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow of patient with hematological malignant diseases. Leuk. Lymphoma 2008, 49, 2187–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campioni, D.; Rizzo, R.; Stignani, M.; Melchiorri, L.; Ferrari, L.; Moretti, S.; Russo, A.; Bagnara, G.P.; Bonsi, L.; Alviano, F.; et al. A decreased positivity for CD90 on human mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) is associated with a loss of immunosuppressive activity by MSCs. Cytometry B Clin. Cytom. 2009, 76, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blau, O.; Baldus, C.D.; Hofmann, W.-K.; Thiel, G.; Nolte, F.; Burmeister, T.; Türkmen, S.; Benlasfer, O.; Schümann, E.; Sindram, A.; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia patients have distinct genetic abnormalities compared with leukemic blasts. Blood 2011, 118, 5583–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jann, J.-C.; Mossner, M.; Riabov, V.; Altrock, E.; Schmitt, N.; Flach, J.; Xu, Q.; Nowak, V.; Obländer, J.; Palme, I.; et al. Bone marrow derived stromal cells from myelodysplastic syndromes are altered but not clonally mutated in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azuma, K.; Umezu, T.; Imanishi, S.; Asano, M.; Yoshizawa, S.; Katagiri, S.; Ohyashiki, K.; Ohyashiki, J.H. Genetic variations of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells derived from acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome by targeted deep sequencing. Leuk. Res. 2017, 62, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, L.-J.; El-Osta, A.; Karagiannis, T.C. gammaH2AX: a sensitive molecular marker of DNA damage and repair. Leukemia 2010, 24, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, M.K.; Cimprich, K.A. Causes and consequences of replication stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kode, A.; Manavalan, J.S.; Mosialou, I.; Bhagat, G.; Rathinam, C.V.; Luo, N.; Khiabanian, H.; Lee, A.; Murty, V.V.; Friedman, R.; et al. Leukaemogenesis induced by an activating β-catenin mutation in osteoblasts. Nature 2014, 506, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zambetti, N.A.; Bindels, E.M.J.; Kenswill, K.; Mylona, A.M.; Adisty, N.M.; Hoogenboezem, R.M.; Sanders, M.A.; Cremers, E.M.P.; Westers, T.M.; et al. Massive parallel RNA sequencing of highly purified mesenchymal elements in low-risk MDS reveals tissue-context-dependent activation of inflammatory programs. Leukemia 2016, 30, 1938–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medyouf, H.; Mossner, M.; Jann, J.-C.; Nolte, F.; Raffel, S.; Herrmann, C.; Lier, A.; Eisen, C.; Nowak, V.; Zens, B.; et al. Myelodysplastic cells in patients reprogram mesenchymal stromal cells to establish a transplantable stem cell niche disease unit. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 824–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.C.; Basu, S.K.; Zhao, X.; Chien, S.; Fang, M.; Oehler, V.G.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Becker, P.S. Mesenchymal stromal cells derived from acute myeloid leukemia bone marrow exhibit aberrant cytogenetics and cytokine elaboration. Blood Cancer J. 2015, 5, e302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradi, G.; Baldazzi, C.; Očadlíková, D.; Marconi, G.; Parisi, S.; Testoni, N.; Finelli, C.; Cavo, M.; Curti, A.; Ciciarello, M. Mesenchymal stromal cells from myelodysplastic and acute myeloid leukemia patients display in vitro reduced proliferative potential and similar capacity to support leukemia cell survival. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, R.A.; Wobus, M.; List, C.; Wehner, R.; Schönefeldt, C.; Brocard, B.; Mohr, B.; Rauner, M.; Schmitz, M.; Stiehler, M.; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells from patients with myelodyplastic syndrome display distinct functional alterations that are modulated by lenalidomide. Haematologica 2013, 98, 1677–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyh, S.; Rodríguez-Paredes, M.; Jäger, P.; Koch, A.; Bormann, F.; Gutekunst, J.; Zilkens, C.; Germing, U.; Kobbe, G.; Lyko, F.; et al. Transforming growth factor β1-mediated functional inhibition of mesenchymal stromal cells in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2018, 103, 1462–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-G.; Xu, W.; Yu, H.-P.; Fang, B.-L.; Wu, S.-H.; Li, F.; Li, W.-M.; Li, Q.-B.; Chen, Z.-C.; Zou, P. Functional characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Lett. 2012, 317, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aanei, C.M.; Eloae, F.Z.; Flandrin-Gresta, P.; Tavernier, E.; Carasevici, E.; Guyotat, D.; Campos, L. Focal adhesion protein abnormalities in myelodysplastic mesenchymal stromal cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2011, 317, 2616–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, Z.; Dighe, N.; Venkatesan, S.S.; Cheung, A.M.S.; Fan, X.; Bari, S.; Hota, M.; Ghosh, S.; Hwang, W.Y.K. Bone marrow MSCs in MDS: contribution towards dysfunctional hematopoiesis and potential targets for disease response to hypomethylating therapy. Leukemia 2019, 33, 1487–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambetti, N.A.; Ping, Z.; Chen, S.; Kenswil, K.J.; Mylona, M.A.; Sanders, M.A.; Hoogenboezem, R.M.; Bindels, E.M.; Adisty, M.N.; Van Strien, P.M.; et al. Mesenchymal Inflammation Drives Genotoxic Stress in Hematopoietic Stem Cells and Predicts Disease Evolution in Human Pre-leukemia. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 19, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyh, S.; Oz, S.; Cadeddu, R.-P.; Fröbel, J.; Brückner, B.; Kündgen, A.; Fenk, R.; Bruns, I.; Zilkens, C.; Hermsen, D.; et al. Insufficient stromal support in MDS results from molecular and functional deficits of mesenchymal stromal cells. Leukemia 2013, 27, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntión, S.; Ramos, T.L.; Diez-Campelo, M.; Rosón, B.; Sánchez-Abarca, L.I.; Misiewicz-Krzeminska, I.; Preciado, S.; Sarasquete, M.-E.; Las Rivas, J. de; González, M.; et al. Microvesicles from Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Are Involved in HPC-Microenvironment Crosstalk in Myelodysplastic Patients. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0146722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelson, A.; Strat, A.N.; Bao, W.; Rosston, P.; Fallon, G.; Ohrn, S.; Zhong, H.; Lobo, C.; An, X.; Yazdanbakhsh, K. Mesenchymal stromal cells lower platelet activation and assist in platelet formation in vitro. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epperson, D.E.; Nakamura, R.; Saunthararajah, Y.; Melenhorst, J.; Barrett, A.J. Oligoclonal T cell expansion in myelodysplastic syndrome: evidence for an autoimmune process. Leuk. Res. 2001, 25, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Sun, Z.; Liu, L.; Chen, B.; Cao, Y.; Li, K.; Zhao, R.C. Impairment in immuno-modulatory function of Flk1(+)CD31(-)CD34(-) MSCs from MDS-RA patients. Leuk. Res. 2007, 31, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, W.; You, Y.; Zou, P. The different immunoregulatory functions of mesenchymal stem cells in patients with low-risk or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. PLoS One 2012, 7, e45675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarhan, D.; Wang, J.; Sunil Arvindam, U.; Hallstrom, C.; Verneris, M.R.; Grzywacz, B.; Warlick, E.; Blazar, B.R.; Miller, J.S. Mesenchymal stromal cells shape the MDS microenvironment by inducing suppressive monocytes that dampen NK cell function. JCI Insight 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, O.F.; Calvi, L.M. Immune Dysfunction, Cytokine Disruption, and Stromal Changes in Myelodysplastic Syndrome: A Review. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, M.; Saito, I.; Kuwata, T.; Yoshida, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Takahashi, M.; Tanizawa, T.; Kamiyama, R.; Hirokawa, K. Overexpression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and interferon (IFN)-gamma by bone marrow cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 1997, 11, 2049–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, A.; Yamashita, T.; Tamura, H.; Zhao, W.; Tsuji, T.; Shimizu, M.; Shinya, E.; Takahashi, H.; Tamada, K.; Chen, L.; et al. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha induce an immunoinhibitory molecule, B7-H1, via nuclear factor-kappaB activation in blasts in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2010, 116, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, A.; Olson, T.S.; Otsuru, S.; Chen, X.; Hofmann, T.J.; Nah, H.-D.; Grisendi, G.; Paolucci, P.; Dominici, M.; Horwitz, E.M. IGF-1-mediated osteoblastic niche expansion enhances long-term hematopoietic stem cell engraftment after murine bone marrow transplantation. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 2193–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodillet, H.; Kreuzer, K.-A.; Monsef, I.; Skoetz, N. Thrombopoietin mimetics for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD009883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, F.; Shi, W.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Chang, C. IGF-IR promotes clonal cell proliferation in myelodysplastic syndromes via inhibition of the MAPK pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 44, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aanei, C.M.; Flandrin, P.; Eloae, F.Z.; Carasevici, E.; Guyotat, D.; Wattel, E.; Campos, L. Intrinsic growth deficiencies of mesenchymal stromal cells in myelodysplastic syndromes. Stem Cells Dev. 2012, 21, 1604–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostovskaya, M.; Anastassiadis, K. Differential expression of surface markers in mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell subpopulations with distinct lineage commitment. PLoS One 2012, 7, e51221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roson-Burgo, B.; Sanchez-Guijo, F.; Del Cañizo, C.; Las Rivas, J. de. Insights into the human mesenchymal stromal/stem cell identity through integrative transcriptomic profiling. BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, W.; Wein, F.; Roderburg, C.; Saffrich, R.; Diehlmann, A.; Eckstein, V.; Ho, A.D. Adhesion of human hematopoietic progenitor cells to mesenchymal stromal cells involves CD44. Cells Tissues Organs 2008, 188, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falconi, G.; Fabiani, E.; Fianchi, L.; Criscuolo, M.; Raffaelli, C.S.; Bellesi, S.; Hohaus, S.; Voso, M.T.; D'Alò, F.; Leone, G. Impairment of PI3K/AKT and WNT/β-catenin pathways in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells isolated from patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Exp. Hematol. 2016, 44, 75–83.e1-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, A.J.I.S.; Goonasekera, H.W.W.; Dissanayake, V.H.W. Phenotypic and Cytogenetic Characterization of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in De Novo Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Anal. Cell. Pathol. (Amst) 2016, 2016, 8012716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, D.; Fei, C.; Guo, J.; Gu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, L.; Li, X.; et al. Down-regulation of Dicer1 promotes cellular senescence and decreases the differentiation and stem cell-supporting capacities of mesenchymal stromal cells in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica 2015, 100, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlaki, K.; Pontikoglou, C.G.; Demetriadou, A.; Batsali, A.K.; Damianaki, A.; Simantirakis, E.; Kontakis, M.; Galanopoulos, A.; Kotsianidis, I.; Kastrinaki, M.-C.; et al. Impaired proliferative potential of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes is associated with abnormal WNT signaling pathway. Stem Cells Dev. 2014, 23, 1568–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellibovsky, L.; Diez, A.; Serrano, S.; Aubia, J.; Pérez-Vila, E.; Mariñoso, M.L.; Nogués, X.; Recker, R.R. Bone remodeling alterations in myelodysplastic syndrome. Bone 1996, 19, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidner, H.; Rauner, M.; Trautmann, F.; Schmitt, J.; Balaian, E.; Mies, A.; Helas, S.; Baschant, U.; Khandanpour, C.; Bornhäuser, M.; et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes and bone loss in mice and men. Leukemia 2017, 31, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimura, R.; Li, L. Shifting in balance between osteogenesis and adipogenesis substantially influences hematopoiesis. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 2, 61–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.J.; Calvi, L.M. The microenvironment in myelodysplastic syndromes: Niche-mediated disease initiation and progression. Exp. Hematol. 2017, 55, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uttley, L.; Indave, B.I.; Hyde, C.; White, V.; Lokuhetty, D.; Cree, I. Invited commentary-WHO Classification of Tumours: How should tumors be classified? Expert consensus, systematic reviews or both? Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 3516–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cree, I.A. The WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1701–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, J.D.; Solary, E.; Abla, O.; Akkari, Y.; Alaggio, R.; Apperley, J.F.; Bejar, R.; Berti, E.; Busque, L.; Chan, J.K.C.; et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1703–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.A.; Peled, A. CXCR4 antagonists: targeting the microenvironment in leukemia and other cancers. Leukemia 2009, 23, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.W.; Ryu, S.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, J.W.; Sung, K.W.; Koo, H.H.; Yoo, K.H. Mesenchymal stem cells in suppression or progression of hematologic malignancy: current status and challenges. Leukemia 2019, 33, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, E.; Sanaat, Z.; Farahzadi, R. Mesenchymal stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia: a focus on mechanisms involved and therapeutic concepts. Blood Res. 2019, 54, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, A.; Coustan-Smith, E.; Behm, F.G.; Raimondi, S.C.; Campana, D. Bone marrow-derived stromal cells prevent apoptotic cell death in B- lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 1992, 79, 2370–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R.; Lam, E.W.-F.; Soeiro, I.; Tisato, V.; Bonnet, D.; Dazzi, F. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit proliferation and apoptosis of tumor cells: impact on in vivo tumor growth. Leukemia 2007, 21, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.W.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, D.S.; Park, H.J.; Jung, H.L.; Lee, J.W.; Sung, K.W.; Koo, H.H.; Yoo, K.H. Human Adipose Tissue Stem Cells Promote the Growth of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cells in NOD/SCID Mice. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2018, 14, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, E.H.; Skah, S.; Ugland, H.; Myklebost, O.; Sandnes, D.L.; Torgersen, M.L.; Josefsen, D.; Ruud, E.; Naderi, S.; Blomhoff, H.K. Bone marrow stroma-derived PGE2 protects BCP-ALL cells from DNA damage-induced p53 accumulation and cell death. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, J.; Boxberger, S.; Jørgensen, B.; Feldmann, S.; Ehninger, G.; Bornhäuser, M.; Werner, C. Mesenchymal stem cells can be differentiated into endothelial cells in vitro. Stem Cells 2004, 22, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.V.; Litovsky, S.; Assad, J.A.R.; Sousa, A.L.S.; Martin, B.J.; Vela, D.; Coulter, S.C.; Lin, J.; Ober, J.; Vaughn, W.K.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into an endothelial phenotype, enhance vascular density, and improve heart function in a canine chronic ischemia model. Circulation 2005, 111, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Sun, R.; Origuchi, M.; Kanehira, M.; Takahata, T.; Itoh, J.; Umezawa, A.; Kijima, H.; Fukuda, S.; Saijo, Y. Mesenchymal stromal cells promote tumor growth through the enhancement of neovascularization. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, B.D.; Elst, A. ter; Kamps, W.A.; Bont, E.S.J.M. de. Bone marrow-derived cells and tumor growth: contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to tumor micro-environments with special focus on mesenchymal stem cells. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2009, 69, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnaird, T.; Stabile, E.; Burnett, M.S.; Lee, C.W.; Barr, S.; Fuchs, S.; Epstein, S.E. Marrow-derived stromal cells express genes encoding a broad spectrum of arteriogenic cytokines and promote in vitro and in vivo arteriogenesis through paracrine mechanisms. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampen, K.R.; Elst, A. ter; Bont, E.S.J.M. de. Vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.R.; Pereira, J.K.N.; Melo Campos, P. de; Machado-Neto, J.A.; Traina, F.; Saad, S.T.O.; Favaro, P. De novo AML exhibits greater microenvironment dysregulation compared to AML with myelodysplasia-related changes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Knox, T.R.; Tschumper, R.C.; Wu, W.; Schwager, S.M.; Boysen, J.C.; Jelinek, D.F.; Kay, N.E. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-PDGF receptor interaction activates bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells derived from chronic lymphocytic leukemia: implications for an angiogenic switch. Blood 2010, 116, 2984–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallongo, C.; Tibullo, D.; Parrinello, N.L.; La Cava, P.; Di Rosa, M.; Bramanti, V.; Di Raimondo, C.; Conticello, C.; Chiarenza, A.; Palumbo, G.A.; et al. Granulocyte-like myeloid derived suppressor cells (G-MDSC) are increased in multiple myeloma and are driven by dysfunctional mesenchymal stem cells (MSC). Oncotarget 2016, 7, 85764–85775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, J.F. de; Laranjeira, A.B.A.; Zanchin, N.I.T.; Otubo, R.; Vaz, T.H.; Cardoso, A.A.; Brandalise, S.R.; Yunes, J.A. Increased CCL2 and IL-8 in the bone marrow microenvironment in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2011, 56, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gañán-Gómez, I.; Wei, Y.; Starczynowski, D.T.; Colla, S.; Yang, H.; Cabrero-Calvo, M.; Bohannan, Z.S.; Verma, A.; Steidl, U.; Garcia-Manero, G. Deregulation of innate immune and inflammatory signaling in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 2015, 29, 1458–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brück, O.; Blom, S.; Dufva, O.; Turkki, R.; Chheda, H.; Ribeiro, A.; Kovanen, P.; Aittokallio, T.; Koskenvesa, P.; Kallioniemi, O.; et al. Immune cell contexture in the bone marrow tumor microenvironment impacts therapy response in CML. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1643–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-G.; Xu, W.; Sun, L.; Li, W.-M.; Li, Q.-B.; Zou, P. The characteristics and immunoregulatory functions of regulatory dendritic cells induced by mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow of patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 1884–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwabo Kamdje, A.H.; Kamga, P.T.; Tagne Simo, R.; Vecchio, L.; Seke Etet, P.F.; Muller, J.M.; Bassi, G.; Lukong, E.; Goel, R.K.; Amvene, J.M.; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells' role in tumor microenvironment: involvement of signaling pathways. Cancer Biol. Med. 2017, 14, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Chen, Y.; Yue, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, X. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells regulate stemness of multiple myeloma cell lines via BTK signaling pathway. Leuk. Res. 2017, 57, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarini, F.; Lonetti, A.; Evangelisti, C.; Buontempo, F.; Orsini, E.; Evangelisti, C.; Cappellini, A.; Neri, L.M.; McCubrey, J.A.; Martelli, A.M. Advances in understanding the acute lymphoblastic leukemia bone marrow microenvironment: From biology to therapeutic targeting. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2016, 1863, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallati, A.; Di Marzo, N.; D’Amico, G.; Dander, E. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs): An Ally of B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (B-ALL) Cells in Disease Maintenance and Progression within the Bone Marrow Hematopoietic Niche. Cancers 2022, 14, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianello, F.; Villanova, F.; Tisato, V.; Lymperi, S.; Ho, K.-K.; Gomes, A.R.; Marin, D.; Bonnet, D.; Apperley, J.; Lam, E.W.-F.; et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells non-selectively protect chronic myeloid leukemia cells from imatinib-induced apoptosis via the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis. Haematologica 2010, 95, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Gorji, S.; Karimpor Malekshah, A.A.; Hashemi-Soteh, M.B.; Rafiei, A.; Parivar, K.; Aghdami, N. Effect of Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Doxorubicin-Induced Fibrosis. Cell J. 2012, 14, 142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, B.; Tian, C.; Guo, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, D.; Qu, F.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Da, W.; et al. c-Myc plays part in drug resistance mediated by bone marrow stromal cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2015, 39, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.Z.; Mak, P.Y.; Chen, Y.; Mak, D.H.; Mu, H.; Jacamo, R.; Ruvolo, V.; Arold, S.T.; Ladbury, J.E.; Burks, J.K.; et al. Anti-apoptotic ARC protein confers chemoresistance by controlling leukemia-microenvironment interactions through a NFκB/IL1β signaling network. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 20054–20067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, M.; Ramasamy, R.; Tan, B.C.; Seow, H.F. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUCB-MSC) inhibit the proliferation of K562 (human erythromyeloblastoid leukaemic cell line). Cell Biol. Int. 2012, 36, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Han, Q.; Liao, L.; Wang, J.; Bian, C.; Li, J.; Yan, X.; Liu, Y.; Shao, C.; et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit cancer cell proliferation by secreting DKK-1. Leukemia 2009, 23, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Chen, N.; Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Xu, F.; Ren, Q.; Lu, S.; Liu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from leukemia patients inhibit growth and apoptosis in serum-deprived K562 cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 28, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, K.; Yang, S.; Ren, Q.; Han, Z.; Lu, S.; Ma, F.; Zhang, L.; Han, Z. p38 MAPK contributes to the growth inhibition of leukemic tumor cells mediated by human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 26, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Shang, Y.; Luo, J. Effect of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from blastic phase chronic myelogenous leukemia on the growth and apoptosis of leukemia cells. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 30, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Chen, D.; Chen, X.; Shao, H.; Huang, S. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit proliferation but maintain survival of Jurkat leukemia cells in vitro by activating Notch signaling. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2014, 34, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Song, N.; Gao, L.; Qiu, H.; Huang, C.; Cheng, H.; Zhou, H.; Lv, S.; Chen, L.; Wang, J. Mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit leukemia/lymphoma cell proliferation in vitro and in a mouse model of allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmadi, V.H.; Tong, C.K.; Vidyadaran, S.; Abdullah, M.; Seow, H.F.; Ramasamy, R. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit proliferation of lymphoid origin haematopoietic tumour cells by inducing cell cycle arrest. Med. J. Malaysia 2010, 65, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hendijani, F.; Javanmard, S.H.; Sadeghi-aliabadi, H. Human Wharton's jelly mesenchymal stem cell secretome display antiproliferative effect on leukemia cell line and produce additive cytotoxic effect in combination with doxorubicin. Tissue Cell 2015, 47, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-M.; Zhang, L.-S. Influence of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on proliferation of chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Ai Zheng 2009, 28, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.S.Y.; Cheong, S.-K. Role of mesenchymal stem cells in leukaemia: Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde? Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 14, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W. Senescence is heterogeneous in mesenchymal stromal cells: kaleidoscopes for cellular aging. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 2923–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.W.; Kim, D.S.; Ryu, S.; Jang, I.K.; Kim, H.J.; Yang, J.M.; Lee, D.-H.; Lee, S.H.; Son, M.H.; Cheuh, H.W.; et al. Effect of ex vivo culture conditions on immunosuppression by human mesenchymal stem cells. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 154919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopp, A.H.; Gupta, A.; Spaeth, E.; Andreeff, M.; Marini, F. Concise review: Dissecting a discrepancy in the literature: do mesenchymal stem cells support or suppress tumor growth? Stem Cells 2011, 29, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez, P.; Catalina, P.; Rodríguez, R.; Melen, G.J.; Bueno, C.; Arriero, M.; García-Sánchez, F.; Lassaletta, A.; García-Sanz, R.; García-Castro, J. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from infants with MLL-AF4+ acute leukemia harbor and express the MLL-AF4 fusion gene. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 3131–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalapour, S.; Eckert, C.; Seeger, K.; Pfau, M.; Prada, J.; Henze, G.; Blankenstein, T.; Kammertoens, T. Leukemia-associated genetic aberrations in mesenchymal stem cells of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 2010, 88, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, O.; Hofmann, W.-K.; Baldus, C.D.; Thiel, G.; Serbent, V.; Schümann, E.; Thiel, E.; Blau, I.W. Chromosomal aberrations in bone marrow mesenchymal stroma cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloblastic leukemia. Exp. Hematol. 2007, 35, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.-L.; Yu, X.-Q.; Zhu, Y.; Ba, R.; Zhu, W.; Xu, W.-R. Expression of integrins in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells derived from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2008, 16, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.-G.; Liang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, W.-M.; Li, Q.-B.; Chen, Z.-C.; Zou, P. Phenotypic and functional comparison of mesenchymal stem cells derived from the bone marrow of normal adults and patients with hematologic malignant diseases. Stem Cells Dev. 2007, 16, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryningen, A.; Wergeland, L.; Glenjen, N.; Gjertsen, B.T.; Bruserud, O. In vitro crosstalk between fibroblasts and native human acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) blasts via local cytokine networks results in increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis of AML cells as well as increased levels of proangiogenic Interleukin 8. Leuk. Res. 2005, 29, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plumas, J.; Chaperot, L.; Richard, M.-J.; Molens, J.-P.; Bensa, J.-C.; Favrot, M.-C. Mesenchymal stem cells induce apoptosis of activated T cells. Leukemia 2005, 19, 1597–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, T. Using mesenchymal stem cells as a therapy for bone regeneration and repairing. Biol. Res. 2015, 48, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.S.Y. Mesenchymal stem cells: angels or demons? J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 459510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingemann, H.; Matzilevich, D.; Marchand, J. Mesenchymal Stem Cells - Sources and Clinical Applications. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2008, 35, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadaran, P.; Rajendran, R.L.; Lee, H.W.; Kalimuthu, S.; Hong, C.M.; Jeong, S.Y.; Lee, S.-W.; Lee, J.; Ahn, B.-C. Extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stem cells activates VEGF receptors and accelerates recovery of hindlimb ischemia. J. Control. Release 2017, 264, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccaro, A.M.; Sacco, A.; Maiso, P.; Azab, A.K.; Tai, Y.-T.; Reagan, M.; Azab, F.; Flores, L.M.; Campigotto, F.; Weller, E.; et al. BM mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes facilitate multiple myeloma progression. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 123, 1542–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, L.; Scott, P.G.; Tredget, E.E. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance wound healing through differentiation and angiogenesis. Stem Cells 2007, 25, 2648–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Qian, J.; Li, H.; Romaguera, J.E.; Kwak, L.W.; Wang, M.; Yi, Q. Role of the microenvironment in mantle cell lymphoma: IL-6 is an important survival factor for the tumor cells. Blood 2012, 120, 3783–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, W.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, H.; Li, Q.; Wei, Y. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote the growth and drug-resistance of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by secreting IL-6 and elevating IL-17A levels. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Manero, G.; Chien, K.S.; Montalban-Bravo, G. Myelodysplastic syndromes: 2021 update on diagnosis, risk stratification and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, 1399–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, C.; Garz, A.-K.; Grath, S.; Huberle, C.; Witham, D.; Weickert, M.; Malinverni, R.; Niggemeyer, J.; Kyncl, M.; Hecker, J.; et al. Direct modulation of the bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell compartment by azacitidine enhances healthy hematopoiesis. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 3447–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boada, M.; Echarte, L.; Guillermo, C.; Diaz, L.; Touriño, C.; Grille, S. 5-Azacytidine restores interleukin 6-increased production in mesenchymal stromal cells from myelodysplastic patients. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2021, 43, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Geng, S.; Zhang, H.; Lai, P.; Liao, P.; Zeng, L.; Lu, Z.; Weng, J.; Du, X. Phenotype of mesenchymal stem cells from patients with myelodyplastic syndrome maybe partly modulated by decitabine. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 4457–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastrinaki, M.-C.; Pavlaki, K.; Batsali, A.K.; Kouvidi, E.; Mavroudi, I.; Pontikoglou, C.; Papadaki, H.A. Mesenchymal stem cells in immune-mediated bone marrow failure syndromes. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 2013, 265608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camiolo, G.; Tibullo, D.; Giallongo, C.; Romano, A.; Parrinello, N.L.; Musumeci, G.; Di Rosa, M.; Vicario, N.; Brundo, M.V.; Amenta, F.; et al. α-Lipoic Acid Reduces Iron-induced Toxicity and Oxidative Stress in a Model of Iron Overload. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Kim, Y.; Kang, D.; Kwon, A.; Kim, J.; Min Kim, J.; Park, S.-S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Min, C.-K.; Kim, M. Common and different alterations of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells in myelodysplastic syndrome and multiple myeloma. Cell Prolif. 2020, 53, e12819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishiro, A.; Iwasa, M.; Fujii, S.; Maekawa, T.; Andoh, A.; Tohyama, K.; Takaori-Kondo, A.; Miura, Y. Menatetrenone facilitates hematopoietic cell generation in a manner that is dependent on human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal/stem cells. Int. J. Hematol. 2020, 112, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digirolamo, C.M.; Stokes, D.; Colter, D.; Phinney, D.G.; Class, R.; Prockop, D.J. Propagation and senescence of human marrow stromal cells in culture: a simple colony-forming assay identifies samples with the greatest potential to propagate and differentiate. Br. J. Haematol. 1999, 107, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

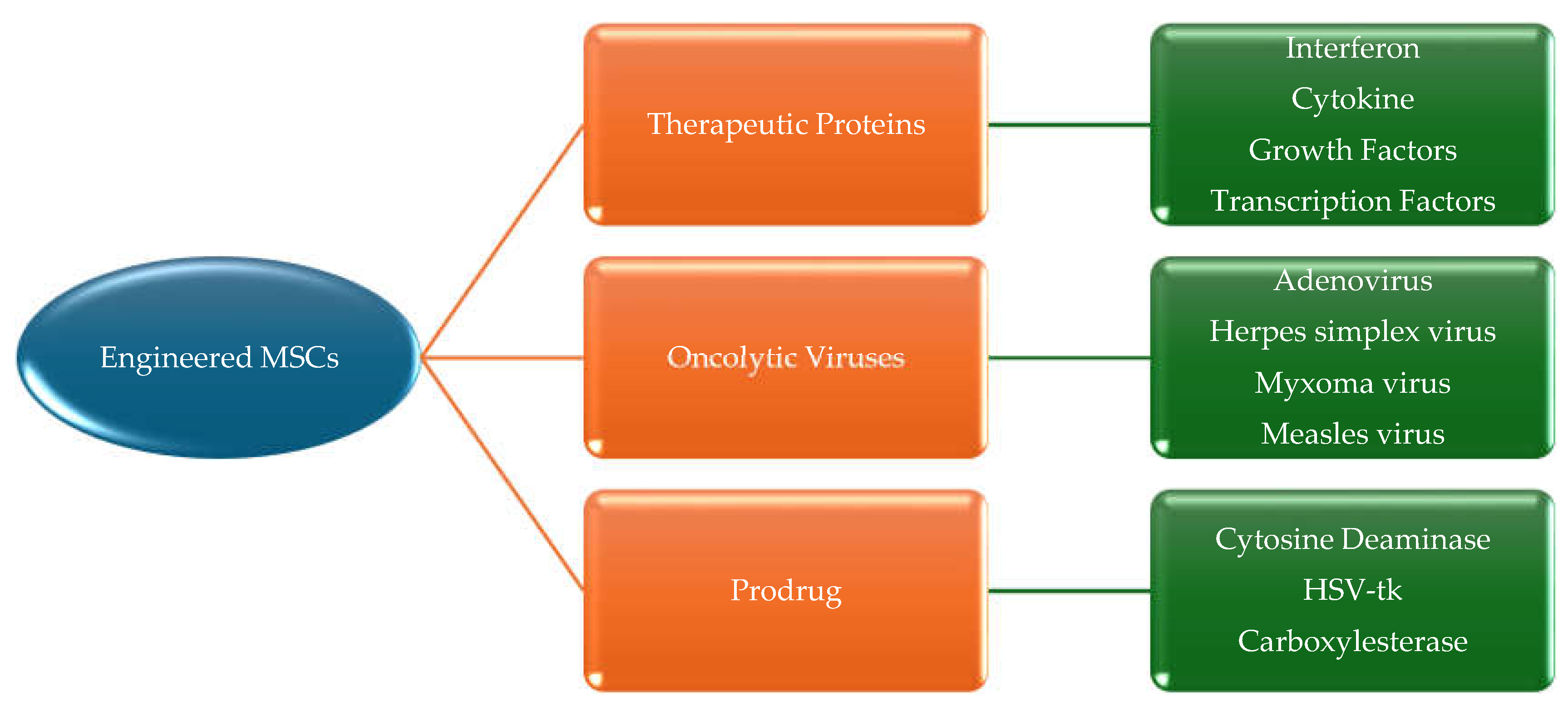

- Hodgkinson, C.P.; Gomez, J.A.; Mirotsou, M.; Dzau, V.J. Genetic engineering of mesenchymal stem cells and its application in human disease therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010, 21, 1513–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.J.; Rameshwar, P. Mesenchymal stem cells in drug/gene delivery: implications for cell therapy. Ther. Deliv. 2012, 3, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermeier, M.; Hennessy, B.T.; Knight, Z.A.; Henneberg, M.; Hu, J.; Kurtova, A.V.; Wierda, W.G.; Keating, M.J.; Shokat, K.M.; Burger, J.A. Isoform-selective phosphoinositide 3'-kinase inhibitors inhibit CXCR4 signaling and overcome stromal cell-mediated drug resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a novel therapeutic approach. Blood 2009, 113, 5549–5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwabo Kamdje, A.H.; Mosna, F.; Bifari, F.; Lisi, V.; Bassi, G.; Malpeli, G.; Ricciardi, M.; Perbellini, O.; Scupoli, M.T.; Pizzolo, G.; et al. Notch-3 and Notch-4 signaling rescue from apoptosis human B-ALL cells in contact with human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Blood 2011, 118, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillozzi, S.; Masselli, M.; Lorenzo, E. de; Accordi, B.; Cilia, E.; Crociani, O.; Amedei, A.; Veltroni, M.; D'Amico, M.; Basso, G.; et al. Chemotherapy resistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia requires hERG1 channels and is overcome by hERG1 blockers. Blood 2011, 117, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Huang, W.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Geng, Q.; Fan, H.; Tan, Y.; Xue, G.; Jiang, X. In vitro effect of adenovirus-mediated human Gamma Interferon gene transfer into human mesenchymal stem cells for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Hematol. Oncol. 2006, 24, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliperta, R.; Welzel, P.B.; Bergmann, R.; Freudenberg, U.; Berndt, N.; Feldmann, A.; Arndt, C.; Koristka, S.; Stanzione, M.; Cartellieri, M.; et al. Cryogel-supported stem cell factory for customized sustained release of bispecific antibodies for cancer immunotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeff, M.; Studeny, M.; Dembinski, J.; Konopleva, M.; Wang, R.-Y.; Yang, H.-Y.; Fueyo, J.; Champlin, R.E.; Lang, F.; Marini, F.C. Mesenchymal stem cells as delivery systems for cancer and leukemia gene therapy. JCO 2004, 22, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessina, A.; Coccè, V.; Pascucci, L.; Bonomi, A.; Cavicchini, L.; Sisto, F.; Ferrari, M.; Ciusani, E.; Crovace, A.; Falchetti, M.L.; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells primed with Paclitaxel attract and kill leukaemia cells, inhibit angiogenesis and improve survival of leukaemia-bearing mice. Br. J. Haematol. 2013, 160, 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Lu, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, F. Exosomes derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells transfer miR-222-3p to suppress acute myeloid leukemia cell proliferation by targeting IRF2/INPP4B. Mol. Cell. Probes 2020, 51, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.; Wang, T.; Cheng, H.; Dong, Y.; Weng, Q.; Sun, G.; Zhou, P.; Wang, K.; Liu, X.; Geng, Y.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress leukemia via macrophage-mediated functional restoration of bone marrow microenvironment. Leukemia 2020, 34, 2375–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J.; Sun, Y. Mesenchymal stem cells: a potential targeted-delivery vehicle for anti-cancer drug, loaded nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2013, 9, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, T.; Luo, M.; Wei, X. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Peng, H.; Yuan, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, D.; Hu, X.; Yang, M.; et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells as vehicles of CD20-specific TRAIL fusion protein delivery: a double-target therapy against non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subtype | % of Peripheral Blasts | % of BM blasts |

|---|---|---|

| Refractory anaemia (RA) | <1 | <5 |

| Refractory anaemia with ringed sideroblasts (RARS) | <1 | <5 |

| Refractory anaemia with excess blasts (RAEB) | <5 | 5-20 |

| Refractory anaemia with excess blasts in transformation (RAEB-T) | ≥5 | 21-30 |

| Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML) (>1000 monocytes/mcL blood) | <5 | 5-20 |

| Subtype | Blood | BM |

|---|---|---|

| Refractory cytopenia with unilineage dysplasia (RCUD) | Single or bicytopenia | Dysplasia in ≥ 10% of one cell line, <5% blasts |

| Refractory anaemia with ring sideroblasts (RARS) | Anaemia, no blasts | ≥ 15% of erythroid precursors with ring sideroblasts, erythroid dysplasia only, <5% blasts |

| Refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia (RCMD) | Cytopenia(s), <1x109/L monocytes | Dysplasia in ≥ 10% of cells in ≥2 hematopoietic lineages, ± 15% ring sideroblasts, <5% blasts |

| Refractory anaemia with excess blasts-1 (RAEB-1) | Cytopenia(s), ≤ 2%-4% blasts, <1x109/L monocytes | Unilineage or multilineage dysplasia, no Auer rods, 5%-9% blasts |

| Refractory anaemia with excess blasts-2 (RAEB-2) | Cytopenia(s), 5%-19% blasts, <1x109/L monocytes | Unilineage or multilineage dysplasia, Auer rods, ± 10%-19% blasts |

| MDS, unclassified (MDS-U) | Cytopenia(s) | Unilineage dysplasia or no dysplasia but characteristics MDS cytogenetics, <5% blasts |

| MDS associated with isolated del(5q) | Anaemia, platelets normal or increased | Unilineage erythroid dysplasia, isolated del(5q), <5% blasts |

| Subtype | Dysplastic lineages | Cytopenia(s) | Ring sideroblasts in erythroid elements of BM | Blasts | Cytogenetics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDS with single lineage dysplasia (MDS-SLD) | 1 | 1 or 2 | RS< 15% | PB<1% BM<5% No Auer rods |

Any, unless fulfils criteria for isolated del(5q) |

| MDS with multilineage dysplasia (MDS-MLD) | 2 or 3 | 1-3 | RS<15% | PB<1% BM<5% No Auer rods |

Any, unless fulfils criteria for isolated del(5q) |

| MDS with ring sideroblasts (MDS-RS) MDS-RS with single-lineage dysplasia (MDS-RS-SLD) |

1 | 1-2 | RS≥15% | PB<1% BM<5% No Auer rods |

Any, unless fulfils criteria for isolated del(5q) |

| MDS-RS with multilineage dysplasia (MDS-RS-MLD) | 2 or 3 | 1-3 | RS≥15% | PB<1% BM<5% No Auer rods |

Any, unless fulfils criteria for isolated del(5q) |

| MDS with isolated del(5q) | 1-3 | 1-2 | None or any | PB<1% BM<5% No Auer rods |

Del(5q) alone or with 1 additional abnormality except -7 or del(7q) |

| MDS with excess blasts (MDS-EB) MDS-EB1 |

0-3 | 1-3 | None or any | PB 2~4% or BM 5~9% No Aur rods |

Any |

| MDS-EB2 | 0-3 | 1-3 | None or any | PB 5~19% or BM 10%~19% or Auer | Any |

| MDS-U with 1% PB blast | 1-3 | 1-3 | None or any | PB= 1%, BM <5%, Auer rods | Any |

| With SLD and pancytopenia | 1 | 3 | None or any | PB<1% BM<5% No Auer rods |

Any |

| Defining cytogenetic abnormality | 0 | 1-3 | <15% | PB<1% BM<5% No Auer rods |

MDS defining abnormality |

| Refractory cytopenia in childhood (RCC) | 1-3 | 1-3 | None | PB<2% BM<5% No Auer rods |

Any |

| MDS with defining genetic abnormalities | Blasts |

| MDs with low blasts and isolated 5q deletion | <5% BM and <2% PB |

| MDS with low blasts and SF3B1 mutation | <5% BM and <2% PB |

| MDS with biallelic TP53 inactivation | <20% BM and PB |

| MDS with defining morphological abnormalities | |

| MDS with low blasts (MDS-LB) | |

| MDS, hypoplastic (MDS-h) | |

| MDS with increased blasts (MDS-IB) | |

| MDS-IB1 | 5%-9% BM or 2%-4% PB |

| MDS-IB2 | 10%-19% BM; or 2%-19% PB |

| MDS with fibrosis | 5%-19% BM; or 2%-19% PB |

| Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prognostic variable | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 |

| BM blasts | <5% | 5-10% | - | 11-20% | 21-30% |

| Karyotype | Good | Intermediate | Poor | - | - |

| Cytopenia(s) | 0-1 | 2-3 | - | - | - |

| Total score | Risk groups | Median survival (yrs) | Median time to 25% acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) evolution (yrs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Low | 5.7 | 9.4 |

| 0.5-1 | INT-1 | 3.5 | 3.3 |

| 1.5-2 | INT-2 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| ≥2.5 | High | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Category | Models | Pros | Cons | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | BM transduction/transplantation | Good transplantation | No MDS-AML transformation | MLD-PLD/RUNX1-291fs BMT model |

| Gene editing/modification | Controlled gene expression MDS-AML transformation Studying mutations in particular genes |

Complex operation including embryo culture, microscope injection, and vector construction Long and expensive production cycle |

5q model Tumour suppressor model RAS mouse model Tyrosine kinase model |

|

| Xenotransplantation | Simple process Screening of targeted drugs |

Low rate of tumorigenesis | Cells derived from MDS patients were injected directly to immunodeficient mice. Subcutaneous transplantation model of human MDS cell line SKM-I |

|

| Induced animal model | Simple process MDS-AML transformation |

Unstable biological property Harmful to environment |

Benzene induced model Alkylation reagent induced model Radiation induced model |

|

| Rat | Chemical induced model | Simple process MDS-AML transformation |

Unstable biological property Harmful to environment |

Dimethylbenzanthracene (DMBA) induced model |

| Zebrafish | Genetically engineered model | Controlled gene expression Studying mutations in certain genes High throughput |

Long and expensive production cycle Non-mammalian vertebrate which is different from a patient |

c-myb-gfb model |

| MSCs type | Tumour model | Findings | Proposed mechanism | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse BMSCs | ALL (P388) and B-lymphoma (A20) | Inhibit leukaemia/lymphoma cell growth | Induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of tumour cells | Song et al (2015) |

| Human BMSCs | CML (BV173) and T-ALL (Jurkat) | Inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells | Induction of cell cycle arrest of leukaemic cells | Sarmadi et al (2010) |

| UC-MSCs | CML (K562) | Exert anti-proliferative effect on leukaemia cells | Paracrine signalling and secretion of substances by the secretome | Hendijani et al (2015) |

| Human AT-MSCs | AML (HL-60) and CML (K562) | Inhibit the proliferation of leukaemic cells | Secretion of DKK-1 | Zhu Y et al (2009) |

| Human BMSCs | CML (patient’s cells) | Inhibits the proliferation of CML cells | Production of IFN-a | Zhang HM et al (2009) |

| Human BMSCs | CML (K562) | Inhibit the proliferation of CML cells | Activation of caspase3 and most probably production of CINC-1 and TIMP-1 | Fathi et al (2019) |

| Human UC-MSCs | CML (K562) | Inhibit the proliferation of K562 cells | Cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 by IL-6 and IL-8 | Fonseka et al (2012) |

| Human adipose tissue-MSCs | CML (K562) and AML HL-60) | Inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells | Cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 by DKK-1 secretion | Zhu et al (2009) |

| Leukaemia patient’s BMSCs | CML (K562) | Inhibit apoptosis and growth of leukaemia cells | Cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 and induction of apoptosis via phosphorylation of Bad and Akt proteins | Wei et al (2009) |

| Human UC-MSCs | AML (HL-60) and CML (K562) | Inhibit the growth of cancer cells | Cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 and phosphorylation of p38 MAPK | Tian et al (2010) |

| Human BMSCs and CML patient’s BMSCs | CML (K562 and patient’s cells) | Increase the anti-apoptotic capacity of cancer cells | Regulation of apoptosis-associated protein expression and activation of the Wnt signalling pathway | Han et al (2013) |

| Human UC-MSCs | T-ALL (Jurkat cell line) | Inhibit the proliferation of Jurkat cells | Activation of Notch signalling pathway | Yuan et al |

| MSC type | Tumour/Disease model | Findings | Proposed mechanism | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient derived BMSCs | MDS | Improvement of proliferation and osteogenic capacity of BMSCs with their increased support of HSPCs | Restoring aberrant DNA methylation of BMSCs | Geyh et al (2013) |

| Patient derived BMSCs | MDS | Improvement of the negative impact of MSCs on haematopoiesis by the support of MSCs on healthy HSPC expansion | Regulation of genes related to IFN-γ and ECM receptor interaction pathways by AZA for the support of haematopoiesis | Wenk et al (2018) |

| Patient derived BMSCs | MDS | Improvement of inflammatory environment through AZA | Reducing the level of IL-6 in MDS-MSCs | Boada et al (2016) |

| Patient derived BMSCs | MDS | Improvement of haematopoiesis through AZA | Normalising the BMME and reversing MSCs ability of osteogenic differentiation and proliferation | Poon et al (2019) |

| Patient derived BMSCs | MDS | Improvement of BMSCs’ capacity of supporting normal HSPCs through lenalidomide | Decreasing the secretion of CXCL12 | Ferrer et al (2013) |

| Patient derived BMSCs | MDS | Reducing the ability of MSCs to induce the differentiation of T cells into Tregs and improvement of MDS-MSC senescence through decitabine | Decreasing PD-L1 and CDKN1A expression | Pang et al (2019) |

| Patient derived BMSCs | MDS | Suppression of the adhesion of leukaemic cells to the stroma | Targeting CXCR4-CXCL12 axis | Kastrinaki et al (2013) |

| Human BMSCs | MDS | Decrease in autophagy | Decreasing ROS and iron content | Camiolo et al (2019) |

| Human BMSCs | MDS | Improvement of the proliferation activity of MSCs and BMSCs support in haematopoiesis | Inducing CDKN2A and enhancing apoptosis | Fujishiro et al (2020) |

| Patient derived BMSCs | MDS | Restoration of osteogenic differentiation of MSCs | Blocking TGFβ signalling with SD-208 | Geyh et al (2018) |

| BMSCs | CML | Regression of tumour and improvement of survival rates | Production of interferon by engineered MSCs for drug delivery | Andreeff et al (2004) |

| Mice BMSCs | T-ALL | Decrease in tumour burden and improvement of survival rate | Intra-BM treatment with MSCs | Xia et al (2020) |

| Human BMSCs | CML (K562) | Reduction in the proliferation of CML cells and induction of apoptosis | Transfer of hIFN-γ gene to MSCs and co-culture of genetically modified MSCs and K562 cells | Li et al (2006) |

| Human BMSCs | AML | Increase in the survival of MSCs | Genetically engineered MSCs to release anti-CD33-anti-CD3 bispecific antibody | Aliperta et al (2017) |

| Human BMSCs | Human T-cell ALL (MOLT-4) and mouse CLL (L1210) | Inhibition of leukaemic cells and angiogenesis | MSCs loaded with PTX | Pessina et al (2013) |

| Human UC-MSCs | CML (K562) | Suppression of leukaemic cell proliferation | MSC EVs combined with doxorubicin | Hendijani et al (2015) |

| Rat BMSCs | ALL (Ball-1) and K562 (CML) | Suppression of leukaemic cell proliferation | Targeting macrophages through MSCs-primed with sLipo leva | Liu et al (2022) |

| Human BMSCs | AML (THP-1) | Inhibition of AML cell proliferation and induction of AML apoptosis | Targeting IRF2 and delivering miR-222-3p via exosomes released from BMSCs | Zhang et al (2022) |

| NCT No. | Phase | Interventions | Treatment | Cancer Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04565665 | I/II | Cord blood MSCs | MSCs IV followed by a second fusion of MSCs within 7 days of the first one. | Hematopoietic and lymphoid cell neoplasm |

| NCT03184935 | I/II | Cord blood MSCs | Allogeneic umbilical cord MSCs and decitabine (20mg/m^2) | Myelodysplastic syndromes |

| NCT02181478 | I | MSCs | Reduced-intensity conditioning with cyclophosphamide, fludarabine (with total body irradiation) or fludarabine and melphalan followed by co-transplantation of intra-osseous umbilical cord blood and MSCs. | Hematologic malignancies |

| NCT01624701 | I/II | Bone marrow MSCs | Clinically ex-vivo expanded cord blood cells are comprised of stem cell factor, Flt3 ligand, thrombopoietin, IGFBP2, and MSC co-culture. | Expanding umbilical cord blood-derived blood stem cells for treating leukaemia, lymphoma, and myeloma |

| NCT01092026 | I/II | Cord blood transplantation + MSCs | Umbilical cord blood hematopoietic stem cell transplantation co-infused with third-party MSCs | Hematologic malignancies |

| NCT01045382 | II | Hematopoietic stem cells + MSCs | 1,5-3,0 x 10E6 MSC/Kg with fludarabine and 2 Gy total body irradiation followed by HLA-is matched PBSC | Leukaemia, lymphoma, and myeloma |

| NCT01129739 | II | Cord blood MSCs | 1.0E+6 MSC/kg, Intravenous | Myelodysplastic syndromes |

| NCT05672420 | Ib/II | Umbilical cord-derived MSCs | RP2D, Intravenous | Hematologic malignancies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).