Submitted:

27 June 2024

Posted:

28 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Context

1.2. Experiences from Previous Research Project

1.3. Public and Patient Involvement (PPI)

1.3.1. General Considerations

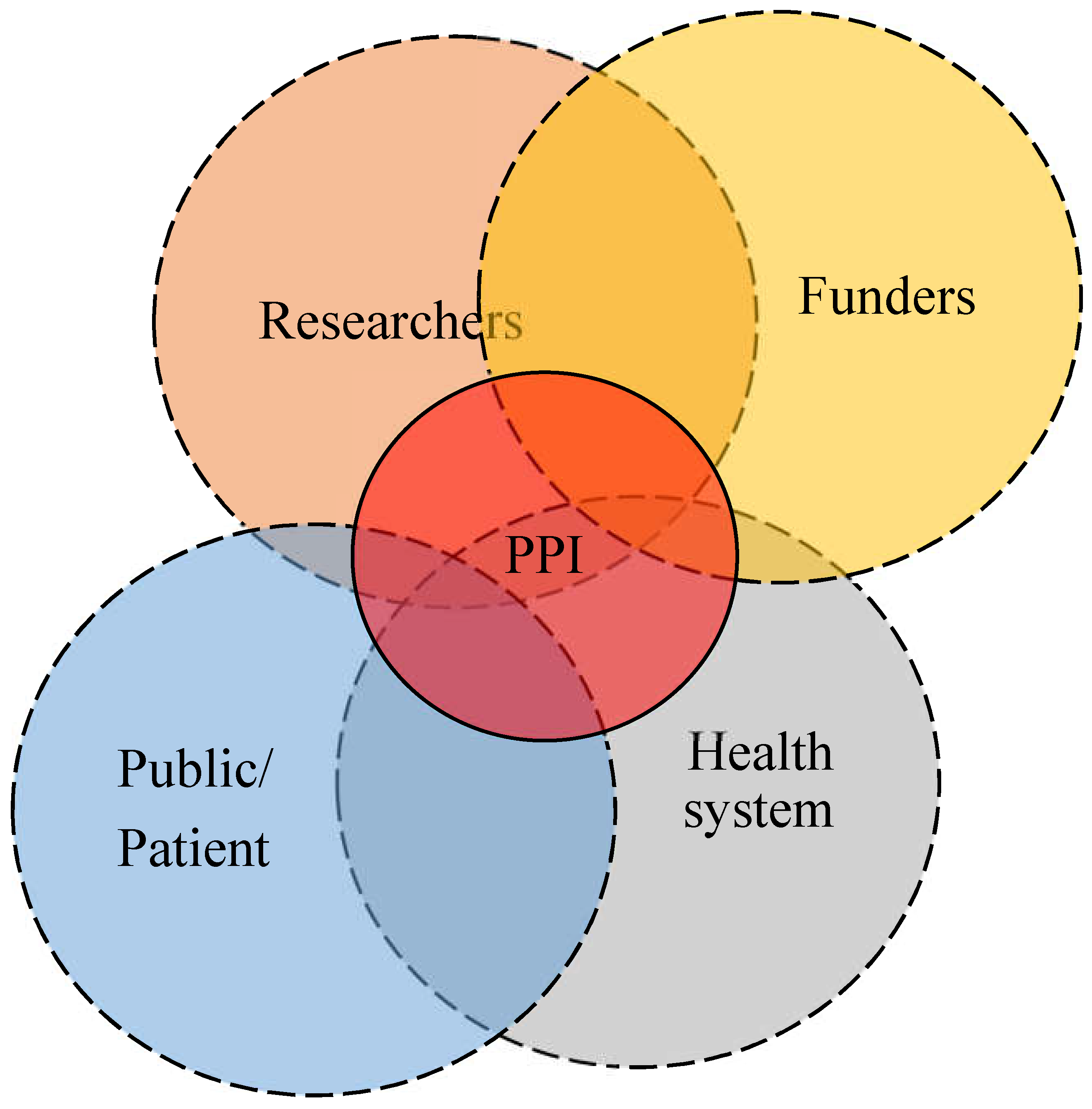

1.3.2. The Concept of PPI

2. Method

2.1. Exploring Migration PPI, through an Interactive In-Depth Exchange: PPI Group in Health Research during COVID-19 Pandemic

2.2. Selection of Volunteers

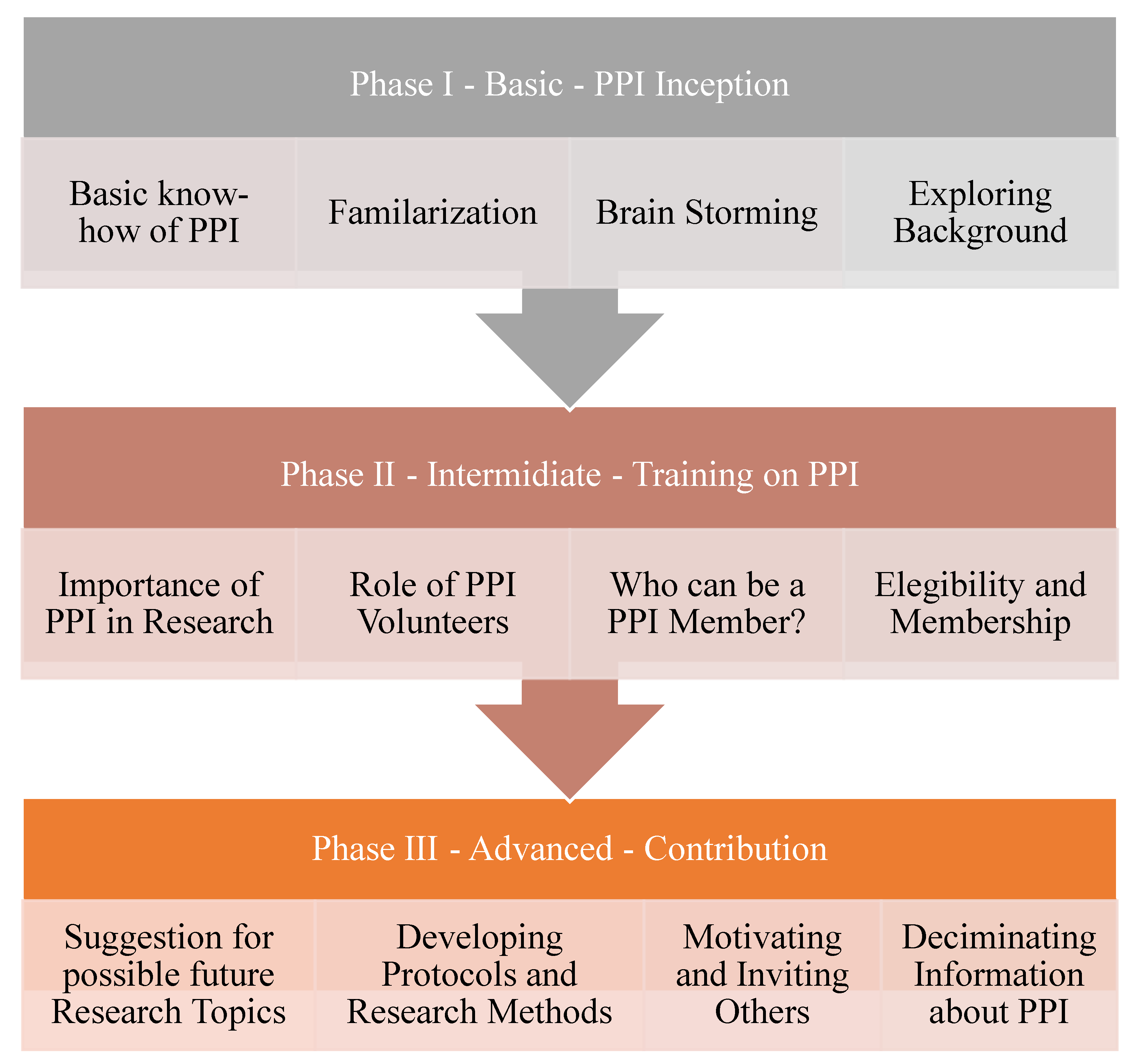

2.3. Stages of Establishing a PPI for Migration Health Research

2.4. Realization of the PPI Establishment

2.5. Criteria for Evaluation, Including Quantitative and Qualitative Indicators

3. Results

3.1. Reaching out Participants

3.2. Orientation and Clarification of PPI among Migrants

3.3. Willingness to Attend PPI Migration Health Research Program

3.4. Engagements and Contribution of Participants

3.5. Inputs and Propositions of PPI Members

4. Discussion

4.1. Role and Effect of PPI on Raising Awareness of Research Importance

‘Health research is a means of educating the community, and provides an opportunity of gathering information for educating the public and raising awareness, and can positively impact the health of the people’ (37-year-old male migrant from Eritrea).

‘I benefited from partaking in a migration health screening research project. Asymptomatic parasitic infectious diseases were diagnosed. Hence, self-involvements in health-related research projects benefits the participants both through access to medical care service and increasing awareness of the health system, and related information’ (40-year-old male migrant from Eritrea).

‘It is obvious that there are symptomatic and asymptomatic health problems. We have difficulties, and problems. We consider ourselves as healthy; however, we know that we are not. It was only after we were diagnosed, and participated in research projects such as the migration health study, conducted by Swiss TPH, that we became aware of some health issues. If our participation in research is low, you (the researchers) need to raise our awareness’ (40-year-old male migrant from Eritrea).

‘Only the people themselves know best about their problems’ (38-year-old male migrant form Eritrea).

‘Most studies [medical research studies including mental health] focus on diseases instead of the causes for the diseases. Among the causes to be mentioned, for example, are worries and stress leading to different diseases. It is better to concentrate of the root cause for those worries, stressors and others’ (40-year-old male migrant from Eritrea).

‘It is not good to generalize among refugees, for example among Eritreans and Syrians. As Eritreans, we are different from the Syrians, many they arrive with their families together, but we [Eritreans] arrive through challenges of long migration journeys, and mostly we live alone by ourselves. To solve all those problems, specific treatment procedures need to be adapted to each group, rather than generalizing all together’ (33-year-old male migrant from Eritrea).

4.2. PPI on Communicating Healthcare System Accessibilities and Utilization

‘Even though there are ample healthcare access facilities here in Switzerland, how can we improve our awareness, so that we can utilize the health system provided for us effectively and efficiently?’ (28-year-old female migrant from Eritrea).

‘Due to limited awareness, we are not utilizing the system. Initiatives such as those by Dr. Fana Asefaw, are helping women to increase awareness of women health’.

‘Medically it’s the best approach, to gradually increase the medications doses and start with the least ones, but the environment and the culture that we came from make it hard for us to understand that. In Syria, we directly take Augmentin 1000 mg for example for a slight flu with fever, and this high consumption of antibiotics did harm us. Now the lower doses does not work on our bodies at all’.

‘We did not get an explanation as refugees about the type of health insurance we have and the coverage’ (33-year-old male Syrian participant).

‘The insurance contracts is too hard to cancel, they need reasons and special dates to be cancelled, otherwise will be renewed automatically, the language barrier is a very important element here’ (26-year-old female Syrian participant). Another participant emphasized:

‘Some insurance wages differs from one year to another, we do not understand according to what, how to choose the best one when we have the choice’ (27-year-old female Syrian participant).

4.3. Limitation of the Migration PPI Group Interactive Exchange

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interests

Appendix A. Public and Patient Involvement (PPI): Definition and Background

References

- FSO, Federal Statistics Office (FSO). Switzerland in 23 infographics: Society, economy, territory and environment - Edition March 2023. 2023.

- SEM, Secretariat for Migration (SEM). Foreign Population and Asylum Statistics 2022. 2023.

- Chernet, A.; Neumayr, A.; Hatz, C.; Kling, K.; Sydow, V.; Rentsch, K.; Utzinger, J.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Marti, H.; Nickel, B.; Labhardt, N. D., Spectrum of infectious diseases among newly arrived Eritrean refugees in Switzerland: a cross-sectional study. Int J Public Health 2018, 63 (2), 233-239. [CrossRef]

- Chernet, A.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Sydow, V.; Paris, D. H.; Labhardt, N. D., Mental health and resilience among Eritrean refugees at arrival and one-year post-registration in Switzerland: a cohort study. BMC Research Notes 2021, 14 (1).

- Melamed, S.; Chernet, A.; Labhardt, N. D.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Pfeiffer, C., Social Resilience and Mental Health Among Eritrean Asylum-Seekers in Switzerland. Qual Health Res 2019, 29 (2), 222-236. [CrossRef]

- Hugelius, K.; Semrau, M.; Holmefur, M., Perceived Needs Among Asylum Seekers in Sweden: A Mixed Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17 (14), 4983.

- Ingvarsson, L.; Egilson, S. T.; Skaptadottir, U. D., “I want a normal life like everyone else”: Daily life of asylum seekers in Iceland. Scand J Occup Ther 2016, 23 (6), 416-24.

- Morville, A. L.; Erlandsson, L. K.; Danneskiold-Samsøe, B.; Amris, K.; Eklund, M., Satisfaction with daily occupations amongst asylum seekers in Denmark. Scand J Occup Ther 2015, 22 (3), 207-15. [CrossRef]

- NIHR, Briefing notes for researchers - public involvement in NHS, health and social care research. 2021.

- Rahman, A.; Nawaz, S.; Khan, E.; Islam, S., Nothing about us, without us: is for us. Research Involvement and Engagement 2022, 8 (1).

- Lauzon-Schnittka, J.; Audette-Chapdelaine, S.; Boutin, D.; Wilhelmy, C.; Auger, A.-M.; Brodeur, M., The experience of patient partners in research: a qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. Research Involvement and Engagement 2022, 8 (1). [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Healthy, L., Increasing patient and public involvement in clinical research. The Lancet Healthy Longevity 2024, 5 (2), e83.

- Riva-Rovedda, F.; Viottini, E.; Calzamiglia, M.; Manghera, F.; Manchovas, G.; Dal Molin, A.; Campagna, S.; Busca, E.; Di Giulio, P., Patient and public involvement in research. Assist Inferm Ric 2023, 42 (3), 152-157.

- Lang, I.; King, A.; Jenkins, G.; Boddy, K.; Khan, Z.; Liabo, K., How common is patient and public involvement (PPI)? Cross-sectional analysis of frequency of PPI reporting in health research papers and associations with methods, funding sources and other factors. BMJ Open 2022, 12 (5), e063356. [CrossRef]

- Staley, K.; Sandvei, M.; Horder, M., A problem shared…‘The challenges of public involvement for researchers in Denmark and the UK. 2019.

- Selby, K.; Durand, M.-A.; Von Plessen, C.; Auer, R.; Biller-Andorno, N.; Krones, T.; Agoritsas, T.; Cornuz, J., Shared decision-making and patient and public involvement: Can they become standard in Switzerland? Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen 2022, 171, 135-138.

- Wyss, K.; Bechir, M.; Schelling, E.; Daugla, D. M.; Zinsstag, J., [Health care services for nomadic people. Lessons learned from research and implementation activities in Chad]. Med Trop (Mars) 2004, 64 (5), 493-6.

- Zinsstag, J.; Hediger, K.; Osman, Y. M.; Abukhattab, S.; Crump, L.; Kaiser-Grolimund, A.; Mauti, S.; Ahmed, A.; Hattendorf, J.; Bonfoh, B.; Heitz-Tokpa, K.; Berger González, M.; Bucher, A.; Lechenne, M.; Tschopp, R.; Obrist, B.; Pelikan, K., The Promotion and Development of One Health at Swiss TPH and Its Greater Potential. Diseases 2022, 10 (3). [CrossRef]

- Acka, C. A.; Raso, G.; N’Goran E, K.; Tschannen, A. B.; Bogoch, II; Séraphin, E.; Tanner, M.; Obrist, B.; Utzinger, J., Parasitic worms: knowledge, attitudes, and practices in Western Côte d’Ivoire with implications for integrated control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010, 4 (12), e910.

- Meier, L.; Casagrande, G.; Dietler, D., The Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute: Past, present and future. Acta Tropica 2021, 223, 106077. [CrossRef]

- Söckli, B.; Wiesmann, U.; Lys, J., A Guide for Transboundary Research Partnerships: 11 Principles, 3rd edition (1st edition 2012), Bern, Switzerland. Swiss Commission for Research Partnerships with Developing Countries (KFPE). 2018.

- Schmidlin, T.; Hürlimann, E.; Silué, K. D.; Yapi, R. B.; Houngbedji, C.; Kouadio, B. A.; Acka-Douabélé, C. A.; Kouassi, D.; Ouattara, M.; Zouzou, F.; Bonfoh, B.; N’Goran, E. K.; Utzinger, J.; Raso, G., Effects of hygiene and defecation behavior on helminths and intestinal protozoa infections in Taabo, Côte d’Ivoire. PLoS ONE 2013, 8 (6), e65722. [CrossRef]

- Wallenborn, J. T.; Valera, C. B.; Kounnavong, S.; Sayasone, S.; Odermatt, P.; Fink, G., Urban-Rural Gaps in Breastfeeding Practices: Evidence From Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Int J Public Health 2021, 66, 1604062. [CrossRef]

- Zinsstag, J.; Kaiser-Grolimund, A.; Heitz-Tokpa, K.; Sreedharan, R.; Lubroth, J.; Caya, F.; Stone, M.; Brown, H.; Bonfoh, B.; Dobell, E.; Morgan, D.; Homaira, N.; Kock, R.; Hattendorf, J.; Crump, L.; Mauti, S.; Del Rio Vilas, V.; Saikat, S.; Zumla, A.; Heymann, D.; Dar, O.; de la Rocque, S., Advancing One human-animal-environment Health for global health security: what does the evidence say? Lancet 2023, 401 (10376), 591-604.

- Berger-González, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Zinsstag, J.; Edwards, P.; Krütli, P., Transdisciplinary Research on Cancer-Healing Systems Between Biomedicine and the Maya of Guatemala: A Tool for Reciprocal Reflexivity in a Multi-Epistemological Setting. Qual Health Res 2016, 26 (1), 77-91.

- Erismann, S.; Pesantes, M. A.; Beran, D.; Leuenberger, A.; Farnham, A.; Berger Gonzalez De White, M.; Labhardt, N. D.; Tediosi, F.; Akweongo, P.; Kuwawenaruwa, A.; Zinsstag, J.; Brugger, F.; Somerville, C.; Wyss, K.; Prytherch, H., How to bring research evidence into policy? Synthesizing strategies of five research projects in low-and middle-income countries. Health Research Policy and Systems 2021, 19 (1).

- Cook, N.; Siddiqi, N.; Twiddy, M.; Kenyon, R., Patient and public involvement in health research in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2019, 9 (5), e026514. [CrossRef]

- NIHR-NHS, Patient and public involvement in health and social care research: A handbook for researchers. 2015.

- Brett, J.; Staniszewska, S.; Mockford, C.; Herron-Marx, S.; Hughes, J.; Tysall, C.; Suleman, R., Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expectations 2014, 17 (5), 637-650. [CrossRef]

- Minogue, V.; Cooke, M.; Donskoy, A.-L.; Vicary, P.; Wells, B., Patient and public involvement in reducing health and care research waste. Research Involvement and Engagement 2018, 4 (1). [CrossRef]

- Biggane, A. M.; Olsen, M.; Williamson, P. R., PPI in research: a reflection from early stage researchers. Research Involvement and Engagement 2019, 5 (1). [CrossRef]

- Kaisler, R. E.; Kulnik, S. T.; Klager, E.; Kletecka-Pulker, M.; Schaden, E.; Stainer-Hochgatterer, A., Introducing patient and public involvement practices to healthcare research in Austria: strategies to promote change at multiple levels. BMJ Open 2021, 11 (8), e045618. [CrossRef]

- HRA_NHS, Public involvement in a pandemic: lessons from the UK COVID-19 public involvement matching service. 2021.

- Pandya-Wood, R.; Barron, D. S.; Elliott, J., A framework for public involvement at the design stage of NHS health and social care research: time to develop ethically conscious standards. Research Involvement and Engagement 2017, 3 (1). [CrossRef]

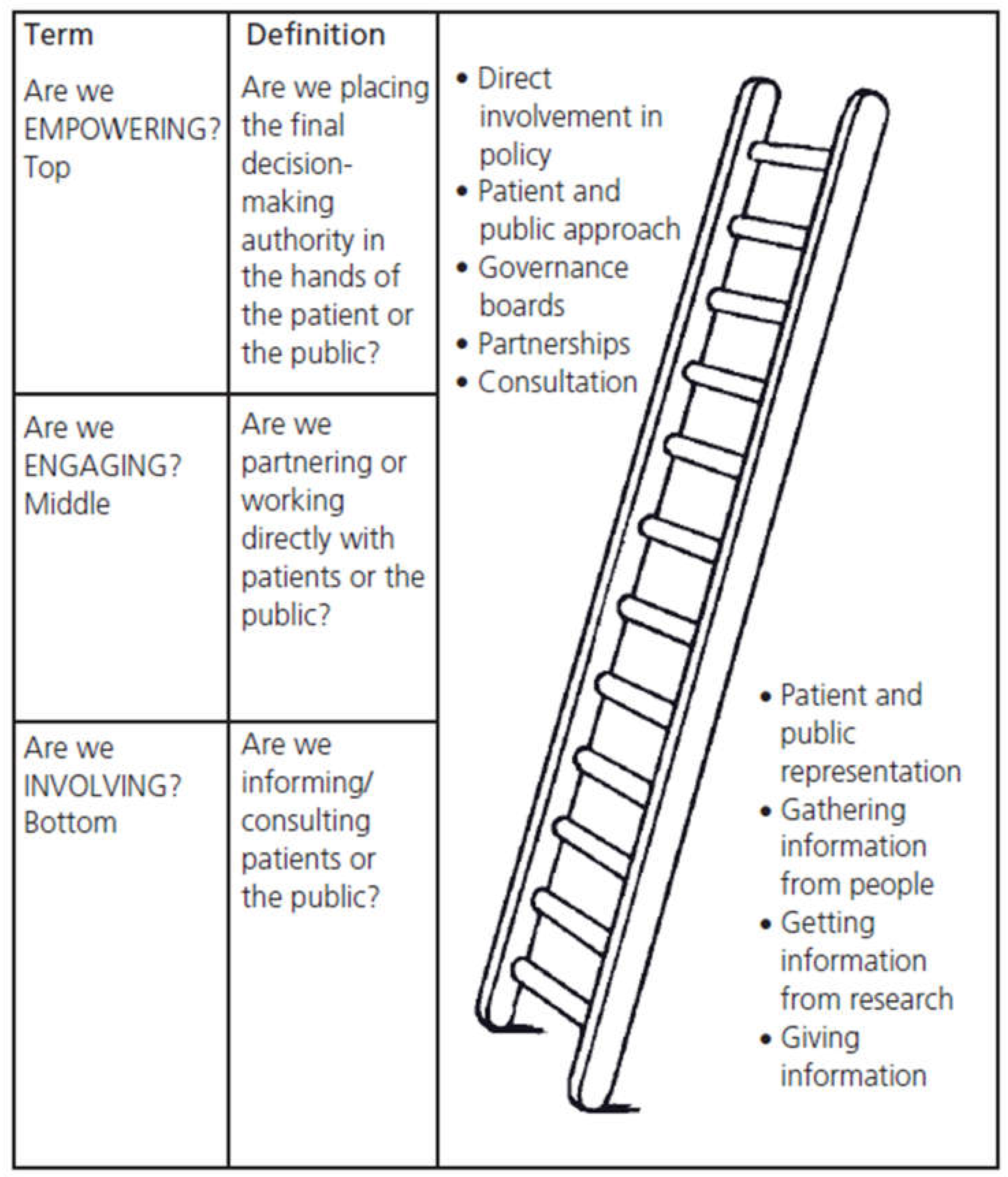

- Cartwright, J.; Crowe, S., Patient and Public Involvement Toolkit. 1st edition ed.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: 2011; p 29.

- HRA-NHS, Health Research Authority-National Health system (HRA-NHS); What is public involvement in research?

- Arnstein, S. R., A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 1969, 35 (4), 216-224. [CrossRef]

- Luna Puerta, L.; Smith, H. E., The “PPI Hawker”: an innovative method for patient and public involvement (PPI) in health research. Res Involv Engagem 2020, 6, 31. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, R.; Staniszewska, S., One small step…. Research Involvement and Engagement 2015, 1 (1).

| Characteristics | Eritrea (N ) |

Syria (N) |

Total N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 5 | 2 | 7 (50.0) |

| Female | 4 | 3 | 7 (50.0) | |

| Median age (years) | 32 | 27 | 30.5 | |

| Educational attainment | Postgraduate | 2 | 0 | 2 (14.3) |

| College/graduate | 3 | 4 | 7 (50.0) | |

| High school | 4 | 1 | 5 (35.7) | |

| Marital status | Married | 9 | 1 | 10 (71.4) |

| Single | 0 | 2 | 2 (14.3) | |

| Divorced | 0 | 2 | 2 (14.3) | |

| Employment status | Employed | 4 | 2 | 6 (42.9) |

| Unemployed | 5 | 3 | 8 (57.1) | |

| Average duration in Switzerland (years) | 7 | 5 | 6 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).