Submitted:

27 June 2024

Posted:

29 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Ethics Committee

2.2. Animal Selection

2.3. Oxidative Stress

2.4. Analysis of Interleukins

2.4.1. Isolation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs)

2.4.2. RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Real-Time PCR

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

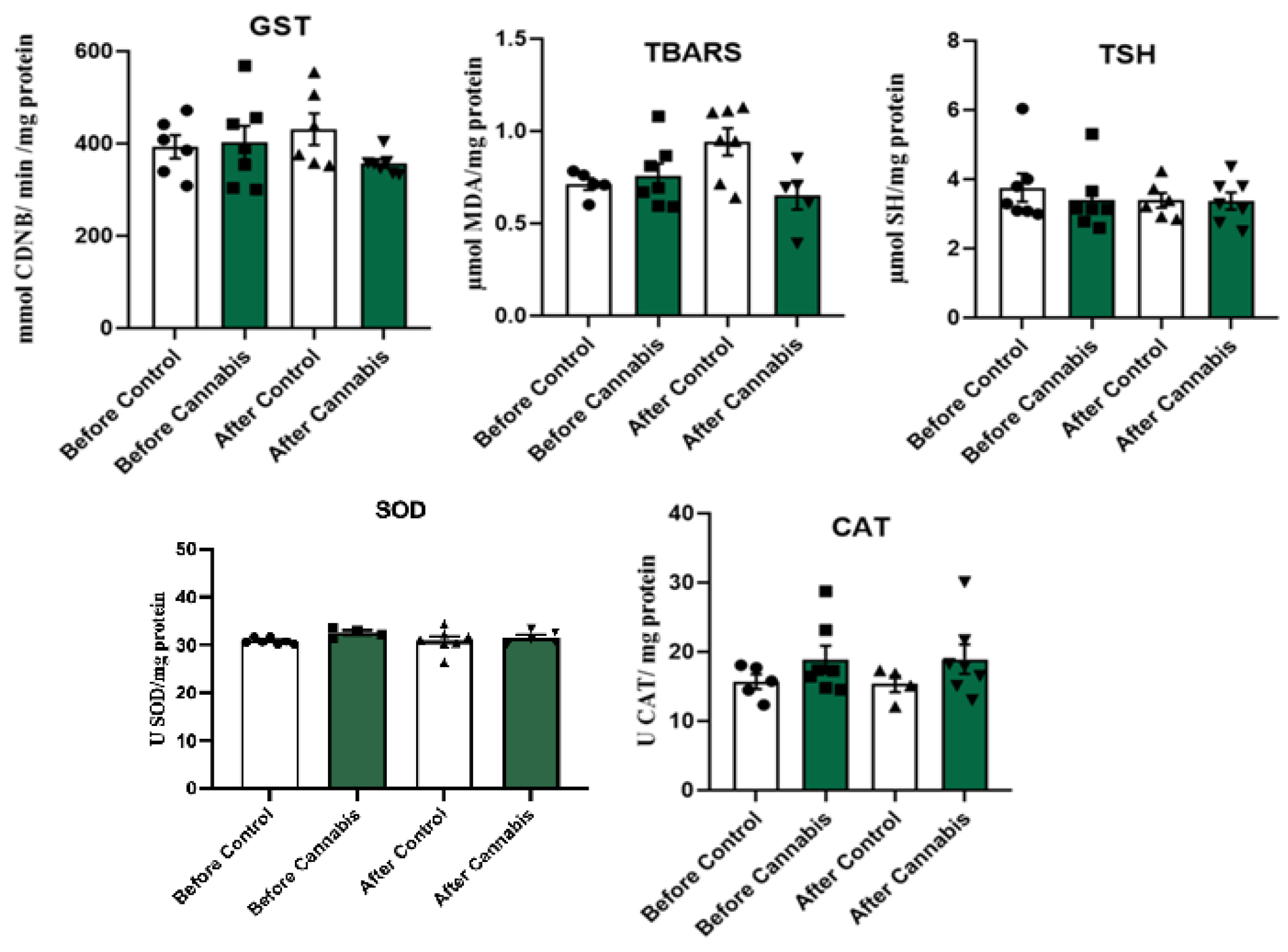

3.1. Oxidative Stress

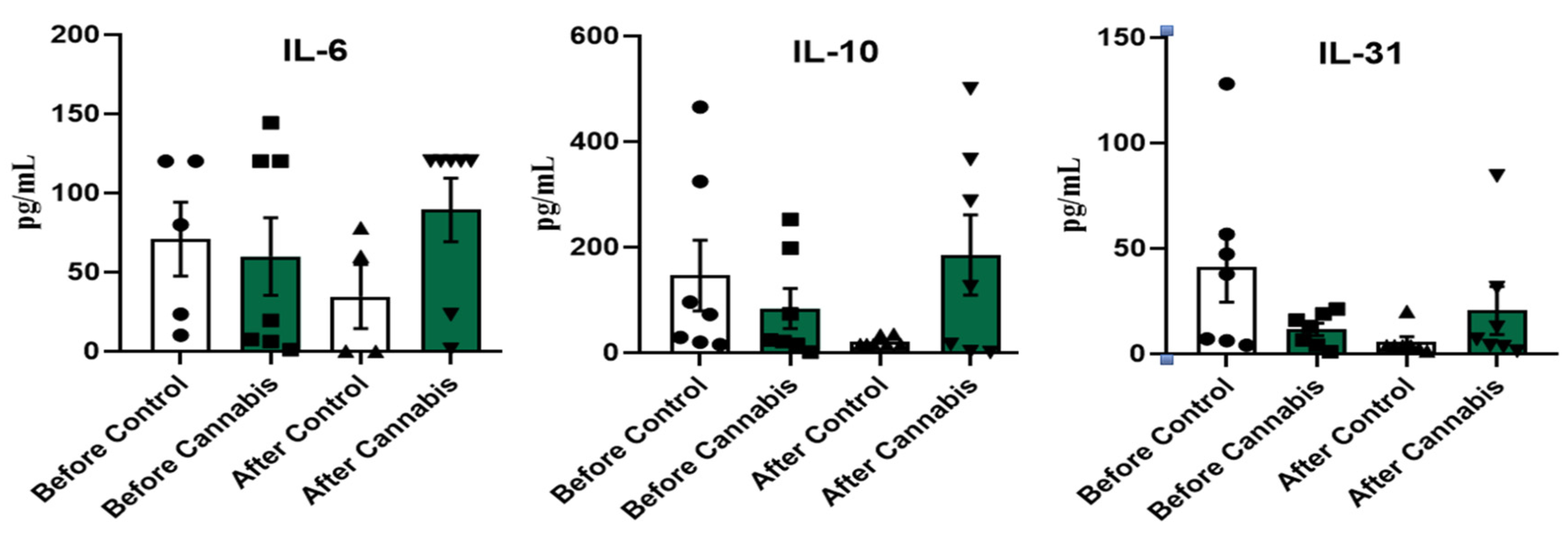

3.2. Interleukins

4. Discussion

4.1. Oxidative Stress

4.2. Interleukins

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Ghezi, Z.Z.; Busbee, P.B.; Alghetaa, H.; Nagarkatti, P.S.; Nagarkatti, M. 2019. Combination of cannabinoids, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD), mitigates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) by altering the gut microbiome. Brain, Behaviour, and Immunity. 2019. 82:25–35. [CrossRef]

- Anil, S.M.; Peeri, H.; Koltai, H. Medical cannabis activity against 423 inflammation: active compounds and modes of action. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2022. v. 13. [CrossRef]

- Asahina, R.; Maeda, S.A. Review of the roles of keratinocyte-derived cytokines and chemokines in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis in humans and dogs. Veterinary Dermatology. 2017. 28:16–e5. [CrossRef]

- Atalay, S.; Jarocka-Karpowicz, I.; Skrzydlewska, E. Antioxidative and Antiinflammatory properties of cannabidiol. Antioxidants. 2020, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertino, L.; Guarneri, F.; Cannavò, S.P.; Casciaro, M.; Pioggia, G.; Gangemi, S. Oxidative Stress and Atopic Dermatitis. Antioxidants. 2020, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgia, F.; Pomi, F.L.; Vaccaro, M.; Alessandrello, C.; Papa, V.; Gangemi, S. Oxidative Stress and Phototherapy in Atopic Dermatitis: Mechanisms, Role, and Future Perspectives. 2022. Biomolecules, 12, 1904. [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, F.; Fasolino, I.; Romano, B.; Capasso, R.; Fracesco, M.; Coppola, D.; Orlando, P.; Battista, G.; Pagano, E.; Di Marzo, V.; Izzo, A.A. Beneficial effect of the nonpsychotropic plant cannabinoid cannabigerol on experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2013. 85:1306–1316. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S.; Aleo, M.; Corum, S.; Zeng, X.; Rincon, G.; Gonzales, A. Exploring the role of cytokines and chemokines in canine aller-gic skin disease. Veterinary Dermatology 2020, 31, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Britch, S.C.; Goodman, A.G.; Wiley, J.L.; Pondelick, A.M.; Craft, R.M. Antinociceptive and immune effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol or cannabidiol in male versus female rats with persistent inflammatory pain. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2020. 373:416–428. [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.C.; Fogaça, M.V.; Sonego, A.B.; Guimarães, F.S. Cannabidiol, neuroprotection and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacology Research. 2016, 112, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiocchetti, R.; Salamanca, G.; De Silva, M.; Gobbo, F.; Aspidi, F.; Cunha, R.Z; Galiazzo, G.; Tagliavia, C.; Sarli, G.; Morini, M. Cannabinoid receptors in the inflammatory cells of canine atopic dermatitis. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2022. 15; 9:987132. [CrossRef]

- Combarros, D.; Cadiergues, M.; Simon, M. Update on canine filaggrin: a review. Veterinary Quarterly. 2020. 40:162–8. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, C.; Marquardt, Y.; Czaja, K.; Wenzel, J.; Frank, J.; LüscherFirzlaff, J.; Lüscher, B.; Baron, J.M. IL-31 regulates differentiation and filaggrin expression in human organotypic skin models. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2012. 129:426– 33. [CrossRef]

- Correa, F.; Hernangómez, M.; Mestre, L.; LorÚa, F.; Spagnolo, A.; Docagne, F.; Di Marzo, V.; Guaza, C. Anandamide enhances IL-10 production in activated microglia by targeting CB2 receptors: Roles of ERK1/2, JNK, and NF-κB. Glia, 2010. 58, 135–147. [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, S.; Borruso, S.; Malandrucco, L.; Spallucci, V.; Maragliano, L.; Perino, R.; D’Agostino, P.; Natoli, E. Cannabis sativa L. may reduce aggressive behavior towards humans in shelter dogs. Scientific Reports. 2021. 11:2773. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.; Deb, A.; Archer, T.; Kaplan, B.L.F. Potential to use cannabinoids as adjunct therapy for dexamethasone: An in vitro study with canine peripheral blood mononuclear cell. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2024, 269, 110727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellman, G.L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 1959. n. 82, p. 70–77. [CrossRef]

- Gedon, N.K.Y.; Mueller, R.S. Atopic dermatitis in cats and dogs: a difficult disease for animals and owners. Clinical and Translational allergy. 2018. 8:41. [CrossRef]

- Gugliandolo, E.; Palma, E.; Cordaro, M.; D´Amico, R.; Peritore, A.F.; Licata, P.; Crupi, R. Canine atopic dermatitis: Role of luteolin as new natural treatment. Veterinary Medicine and Science, 2020. 6:926-932, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gugliandolo, A.; Pollastro, F.; Grassi, G.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E. “In Vitro Model of Neuroinflammation: Eficacy of Cannabigerol, a Non-Psychoactive Cannabinoid,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2018, vol. 19, no. 7, article E1992. [CrossRef]

- Hagib, W.H.; Pabst, M.J.; Jakoby, W.B. Glutathione S-transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1974, 249, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar]

- Hensel, P.; Santoro, D.; Favrot, C.; Hill, P.; Griffin, C. Canine atopic dermatitis: detailed guidelines for diagnosis and allergen identification. BMC Veterinary Research, 2015. 11:196. [CrossRef]

- Henshaw, F.R.; Dewsbury, L.S.; Lim, C.K.; Steiner, G.Z. The Effects of Cannabinoids on Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines: A Systematic Review of In Vivo Studies. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 2021. v. 6, n. 3. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, I.; Mamo, L.B.; Holmes, J.; Mohammed, J.P.; Murphy, K.M.; Bizikova, P. Long-term effects of ciclosporin and oclacitinib on mediators of tolerance, regulatory T-cells, IL-10 and TGF-B, in dogs with atopic dermatitis. Veterinary Dermatology. 2023. 24:107-114. [CrossRef]

- Hoskova, Z.; Svoboda, M.; Satinska, D.; Matiasovic, J.; Leva, L.; Toman, M. Changes in leukocyte counts, lymphocyte subpopulations and the mRNA expression of selected cytokines in the peripheral blood of dogs with atopic dermatitis. Veterinární medicína - Czech, 2015, 518 60:644–53. [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.C.; Almeida, W.P.; Fátima, Â. Glutationa e enzimas relacionadas: papel biológico e importância em processos patológicos. Quím Nova. 2008. 31(5):1170–9. [CrossRef]

- Jentzsch, A.M.; Bachmann, H.; Fürst, P.; Biesalski, H.K. Improved analysis of malondialdehyde in human body fluids. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 1996. 20:251-. [CrossRef]

- Kapun, A.P.; Salobir, J.; Levart, A.; Karcher, G.T.; Svete, A.N.; Kotnik, T. Vitamin E supplementation in canine atopic dermatitis: improvement of clinical signs and effects on oxidative stress markers. Veterinary Record, 2014, 29. [CrossRef]

- Kapun, A.P.; Salobir, J.; Levart, A.; Kotnik, T.; Svete, A.N. Oxidative stress markers in canine atopic dermatitis. Research in Veterinary Science. 2012. 92:469-470. [CrossRef]

- Khaksar, S.; Bigdeli, M.; Samiee, A.; Shirazi-Zand, Z. Antioxidant and antiapoptotic effects of cannabidiol in model of ischemic stroke in rats. Brain Research Bulletin. 2022, 180, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klonowska, J.; Glen, J.; Nowicki, R.J.; Trzeciak, M. New Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis – New Therapeutic Targets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2018, 19, 3086. [CrossRef]

- Koltai, H.; Poulin, P.; Namdar, D. Promoting Cannabis Products to Pharmaceutical Drugs. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2019, 132, 118–120. [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.G.; Tardelli, V.S.; Brietzke, E.; Fidalgo, T.M. Cannabis and inflammatory mediators. European Addiction Research, 2021, 27:26-24. [CrossRef]

- Loewinger, M.; Wakshlag, J.J.; Bowden, D.; Peters-Kennedy, J.; Rosenberg, A. The effect of a mixed cannabidiol and cannabidiolic acidbased oil on client-owned dogs with atopic dermatitis. Veterinary Dermatology, 2022, 33:329-e77. [CrossRef]

- Lorimier, L.P.; Hazzah, T.; Amazonas, E.; Cital, S. Cannabinoids in oncology and immune response. In: Cital, S.; Kramer, K.; Hughston, L.; Gaynor, J.S. Cannabis Therapy in Veterinary Medicine: A complete guide. Springer, 2021, cap. 10, p. 240-249.

- Lubschinski, T.L.; Pollo, L.A.E.; Mohr, E.T.B.; Da Rosa, J.S.; Nardino, L.A.; Sndjo, L.P.; Biavatti, M.W.; Dalmarco, E.M. Effect of Aryl-Cyclohexanones and their derivatives on macrophage polarization in vitro. Inflammation, 2022, vol. 45, n. 4. [CrossRef]

- Majewska, A.; Gajewska, M.; Dembele, K.; Maciejewski, H.; Prostek, A.; Jank, M. Lymphocytic, cytokine and transcriptomic profiles in peripheral blood of dogs with atopic dermatitis. BMC Veterinary Research. 2016. 12:174. [CrossRef]

- Marsella, R. Advances in our understanding of canine atopic dermatitis. Veterinary Dermatology, 2021, 32:547-151. [CrossRef]

- Mariga, C.; Mateus, A.L.S.S.; Dullius, A.I.S.; da Silva, A.P.; Flores, M.M.; Soares, A.V.; Amazonas, E.; Pinto Filho, S.T.L. Dermatological evaluation in dogs with atopic dermatites treated with full-spectrum high cannabidiol oil: a pre study part 1. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 2023, 10:1285384. [CrossRef]

- Martel, B.C.; Lovato, P.; Bäumer, W.; Olivry, T. Translational animal models of atopic dermatitis for preclinical studies. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 2017, 90, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, G.; Magnavacca, A.; Fumagalli, M.; Dell’Agli, M.; Piazza, S.; Sangiovanni, E. Cannabis sativa and skin health: Dissecting the role of phytocannabinoids. Planta Medicinal. 2022, 88(7):492-506. [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Gomes, A.; Boas, I.; Marto, J.; Ribeiro, H. Cannabis-Based Products for the Treatment of Skin Inflammatory Diseases: A Timely Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2022, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massi, P.; Vaccani, A.; Paloralo, D. Cannabinoids, immune system and cytokine network. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 2006, 12, 3135–3146. [CrossRef]

- Massimini, M.; Vedove, E.D.; Bachetti, B.; Di Pierro, F.; Ribecco, C.; D’ Addario, C.; Pucci, M. Polyphenols and Cannabidiol Modulate Transcriptional Regulation of Th1/Th2 Inflammatory Genes Related to Canine Atopic Dermatitis. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 2021, 8:606197. [CrossRef]

- Mccandless, E.E.; Rugg, C.A.; Fici, G.J.; Messamore, J.E.; Aleo, M.M.; Gonzales, A.J. Allergen-induced production of IL-31 by canine Th2 cells and identification of immune, skin, and neuronal target cells. Veterinary Immunology Immunopathology. 2014. 157:42–8. [CrossRef]

- Mccord, J.M.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: na enzymatic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). Journal Biological Chemistry. 1969. v. 244, p. 6049-6055. [CrossRef]

- Mogi, C.; Yoshida, M.; Kawano, K.; Fukuyama, T.; Arai, T. Effects of cannabidiol without delta-9-tetragydrocannabinol on atopic dermatitis: a retrospective assessment of 8 cases. The Canadian Veterinary Journal 2022, 63, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mmoore, P.F.A. review of histiocytic diseases of dogs and cats. Veterinary Pathology. 2014. 51:167–84. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, C.; Otsuka, A.; Kabashima, K. Interleukin-31 and interleukin31 receptor: new therapeutic targets for atopic dermatitis. Experimental Dermatology. 2018. 27:327–31. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.P.; Kiesow, L.A. Enthalpy of decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by catalase at 25° C (with molar extinction coefficients of H2O2 solutions in the UV). Analytical Biochemistry, 1972, 49(2), 474–478. [CrossRef]

- Olivry, T.; Mayhew, D.; Paps, J.S.; Linder, K.E.; Peredo, C.; Rajpal, D.; Holfland, H.; Cote-Sierra, J. Early activation of Th2/Th22 inflammatory and pruritogenic pathways in acute canine atopic dermatitis skin lesions. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2016. 136:1961–9. [CrossRef]

- Olivry, T.; DeBoer, D.J.; Favrot, C.; Jackson, H.A.; Mueller, R.S.; Prélaud, T.P. Treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: clinical practice guidelines from the international task force on canine atopic dermatitis. Veterinary Dermatology, 2010, 21:233–48. [CrossRef]

- Parameswaran, N.; Patial, S. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling in macrophages. Critical Reviews in Eukaryotic Gene Expression. 2010. 20:87–103. [CrossRef]

- Pellati, F.; Borgonetti, V.; Brighenti, V.; Biagi, M.; Benvenuti, S.; Corsi, L. Cannabis sativa L. And nonpsychoactive cannabinoids: Their chemistry and role against oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer. BioMed Research International. 2018, 1691428. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.T.; Cunha, V.E.S.; Schmidt, C.; Magnus, T.; Krause, A. Sensitization study of dogs with atopic dermatitis in the central region of Rio Grande do Sul. Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia, 2015, v.67, n., 6, p. 1533-1538, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.R.; Hackett, B.; O’Driscoll, D.N.; Sun, M.C.; Downer, E.J. Cannabidiol modulation of oxidative stress and signalling. Neuronal Signal; 2021, 5 (3). [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, M.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Bátkai, S.; Patel, V.; Saito, K.; Matsumoto, S. ; Kashiwaya,Y.; Horváth, B.; Mukhopadhyay, B.; Becker, L.; Haskó, G.; Liaudet, L.; Wink, D.A.; Veses, A.; Mechoulam, R.; Pacher, P. Cannabidiol attenuates cardiac dysfunction, oxidative stress, fibrosis, and inflammatory and cell death signaling pathways in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2010, 56, 2115–2125. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, M.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Bátkai, S.; Haskó, G.; Liaudet, L.; Drel, V.R.; Obrosova, I.G.; Pacher, P. Cannabidiol attenuates high glucose-induced endothelial cell inflammatory response and barrier disruption. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 2007, 293, 610–619. [CrossRef]

- Rayman, N.; Lam, K.H.; Laman, J.D.; Simons, P.J.; Löwenberg, B.; Sonneveld, P.; Delwel, R. Distinct expression profiles of the peripheral cannabinoid receptor in lymphoid tissues depending on receptor activation status. Journal of Immunology, 2004, 172:2111–2117. [CrossRef]

- Sunda, F.; Arowolo, A. A molecular basis for the antiinflammatory and antifibrosis properties of cannabidiol. The FASEB Journal, 2020, 34:14083–92, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tamamoto-Mochizuki, C.; Olivry, T. IL-31 and IL-31 receptor expression in acute experimental canine atopic dermatitis skin lesions. Veterinary Dermatology. 2021. 32:631–e169. [CrossRef]

- Tanasescu, R.; Constantinescu, C.S. Cannabinoids and the immune system: An overview. Immunobiology, 2010, 215(8), 588–597. [CrossRef]

- Tortolani, D.; Di Meo, C.; Standoli, S.; Ciaramellano, F.; Kadhim, S.; Hsu, E.; Rapino, C.; Maccarrone, M. Rare Phytocannabinoids Exert Anti-Inflammatory Effects on Human Keratinocytes via the Endocannabinoid System and MAPK Signaling Pathway. International Journal of Molecular Science. 2023, 24, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, K.F.; Ádám, D.; Bíró, T.; Oláh, A. Cannabinoid Signaling in the Skin: Therapeutic potential of the “c(ut)annabinoid” system. Molecules, 2019, 24, 918. [CrossRef]

- Tsukahara, H.; Shibata, R.; Ohta, N.; Sato, S.; Hiraoka, M.; Ito, S.; Noiri, E.; Mayumi, M. High levels of urinary pentosidine, an advanced glycation end product, in children with acute exacerbation of atopic dermatitis: Relationship with oxidative stress. Metabolism, 2003, 52, 1601–1605. [CrossRef]

- Verrico, C.D.; Wesson, S.; Konduri, V.; Hofferek, C.J.; Vazquez-Perez, J.; Blair, E.; Dunner Jr, K.; Salimpour, P.; Decker, W.K.; Halpert, M.M. A randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled study of daily cannabidiol for the treatment of canine osteoarthritis pain. Pain. 2020. 161:2191–2202. [CrossRef]

- Weydert, C.J.; Cullen, J.J. Measurement of superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase in cultured cells and tissue. Nat Protoc. 2010. 5(1):51-66. [CrossRef]

- Zoric, N.; Horvat, I.; Kopjar, N.; Vucemilovic, A.; Kremer, D.; Tomic, S.; Kosalec, I. Hydroxytyrosol expresses antifungal activity in vitro. Curr Drug Targets, 2013, 14:992-998. [CrossRef]

| Group | Sex | Age | Breed | Age of disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ||||

| Animal 1 | Male | 12 years | Shih-tzu | 6 months |

| Animal 2 | Female | 1 year | Lhasa apso | 9 months |

| Animal 3 | Female | 5 years | Shih-tzu | 1 year |

| Animal 4 | Female | 1 year | Dachshund | 10 months |

| Animal 5 | Female | 11 years | Shih-tzu | 1 year |

| Animal 6 | Male | 7 years | Shih-tzu | 3 years |

| Animal 7 | Male | 6 years | Dachshund | 3 years |

| CBD | ||||

| Animal 1 | Female | 8 years | Shih-tzu | 6 months |

| Animal 2 | Female | 10 years | Shih-tzu | 3 years |

| Animal 3 | Male | 6 years | Golden Retriever | 1 year |

| Animal 4 | Female | 7 years | Shih-tzu | 3 years |

| Animal 5 | Female | 8 years | Lhasa apso | 2 years |

| Animal 6 | Male | 9 years | Shih-tzu | 1 year |

| Animal 7 | Male | 11 years | Shih-tzu | 3 years |

| d. H2O | Orthophosphoric acid (0,2M) | SERUM | TBA | |

| Test(quadruplicate) | 550 µL | 1 mL | 200 µL | 250 µL |

| ORDER | 1º | 2º | 3º | 4º |

| Group | n | TBARS (µmol) | TSH (µmol) | GST (mmol) | SOD (U) | CAT (U) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| Control | 1 | 0.78421 | 0.9511 | 2.59823 | 2.74486 | 333.401 | 554.747 | 30.056 | 28.2286 | 12.3625 | ** |

| 2 | 1.74781 | 0.71587 | 5.30367 | 2.49516 | 356.421 | 358.009 | 31.644 | 30.4248 | 24.9904 | 27.6665 | |

| 3 | 0.70938 | 1.1289 | 2.77795 | 3.28238* | 404.399 | 506.385* | 30.6962 | 28.0486 | 29.2066 | 17.3095 | |

| 4 | 0.7131 | 0.94617 | 3.64983 | 4.36559 | 360.975 | 376.152 | 30.5356 | 32.5754 | 15.7693 | 16.8921 | |

| 5 | 0.60136 | 0.64099 | 3.15261 | 3.13768 | 357.977 | 755.367 | 30.0909 | 31.1894 | 18.0806 | 12.0895 | |

| 6 | 1.04376 | 1.11017 | 3.13409 | 3.78031 | 346.502 | 352.918 | 30.5945 | 30.1121 | 17.7333 | 15.1305 | |

| 7 | 0.76196 | 1.10178 | 3.13615 | 3.79654 | 335.749 | 438.148 | 31.506 | 33.3308 | 14.4891 | 22.7313 | |

| Mean | 0.757 | 0.942 | 3.393 | 3.371 | 356.489 | 477.389 | 30.7525 | 30.5585 | 18.947 | 18.636 | |

| P value = | 0.2969 | 0.9656 | 0.01563 | 0.788 | 0.6454 | ||||||

| CBD | 1 | 0.66884 | 0.69438 | 3.08442 | 3.72348 | 300.175 | 472.419 | 29.4791 | 30.2396 | 17.2726 | 16.5049 |

| 2 | 0.59395 | 0.61255 | 2.99384 | 2.92304* | 353.695 | 408.548* | 32.1046 | 34.3283* | 28.7575 | 18.2596 | |

| 3 | 0.86726 | 0.9678 | 3.09898 | 4.2361 | 303.553 | 339.894 | 33.0177 | 32.215 | 16.426 | 13.0261 | |

| 4 | 1.0795 | 0.85289* | 6.04083 | 2.85237* | 455.872 | 441.996 | 29.9805 | 31.0952* | 23.159 | 30.0823* | |

| 5 | 0.59001 | 0.70661 | 3.29493 | 3.21848 | 389.773 | 308.881 | 29.7243 | 30.3239 | 14.5043 | 17.8689 | |

| 6 | 0.69374 | 1.86589 | 4.00329 | 2.55150 | 442.471 | 439.683 | 33.5601 | 26.3763 | 17.3806 | 15.0946 | |

| 7 | 0.81189 | 0.39209* | 3.79419 | 3.38714* | 568.803 | 385.939 | 31.3136 | 31.6196* | 14.7987 | 21.6696* | |

| Mean | 0.757 | 0.870 | 3.758 | 3.270 | 402.048 | 399.622 | 31.3114 | 30.8854 | 18.899 | 18.9294 | |

| P value = | 0.6875 | 0.4688 | 0.9558 | 0.7299 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Group | n | IL-6 (pg/mL) |

IL-10 (pg/mL) |

IL-31 (pg/mL) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||

| Control | 1 | 3.56 | 120.26 | 20.37 | 15.67 | 6.32 | 3.94 | |

| 2 | 10.21 | 120.26 | 29.14 | 15.67 | 4.13 | 20.19 | ||

| 3 | 120.26 | 1.22* | 15.67 | 35.25* | 7.21 | 2.75* | ||

| 4 | 80.02 | 120.26 | 465.73 | 15.67 | 47.46 | 3.94 | ||

| 5 | 5.55 | 120.26 | 72.89 | 15.67 | 37.92 | 3.94 | ||

| 6 | 23.5 | 23.19 | 96.34 | 33.53 | 56.76 | 1.39 | ||

| 7 | 120.26 | 120.26 | 324.6 | 15.67 | 128.19 | 3.94 | ||

| Mean | 51.91 | 89.39 | 146.39 | 21.02 | 41.14 | 5.72 | ||

| P value = | 0.5294 | 0.07813 | 0.07813 | |||||

| CBD | 1 | 1 | 0,15 | 1 | 0,8 | 1 | 1,27 | |

| 2 | 144.47 | 78.05* | 24.06 | 287.38* | 16.02 | 31.41 | ||

| 3 | 120.26 | 60.15 | 252.76 | 500.13 | 4.24 | 84.38 | ||

| 4 | 120.26 | 0.2* | 15.67 | 2.33 | 21.32 | 3.41* | ||

| 5 | 19.59 | 120.26 | 73.54 | 125.21 | 12.96 | 6.88 | ||

| 6 | 6.33 | 120.26 | 21.36 | 15.67 | 6.72 | 3.94 | ||

| 7 | 7.55 | 485.63 | 198.23 | 366.01* | 18.95 | 12.7* | ||

| Mean | 59.92 | 123.53 | 83.80 | 185,36 | 11,60 | 20.57 | ||

| P value = | 0.8125 | 0.2188 | 0.9375 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).