1. Introduction

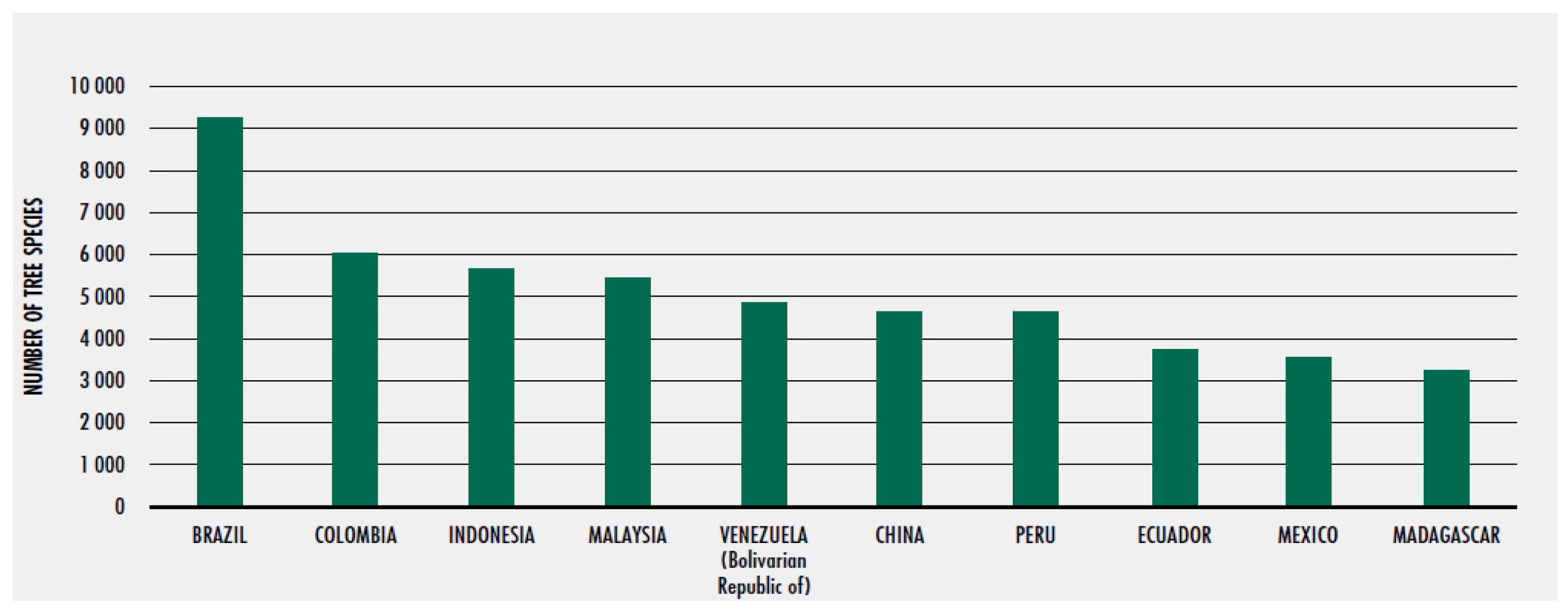

Colombia covers an area of 207 million hectares, of which 114 million hectares are continental area [

1]. It is located in the north-western corner of South America with access to the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Additionally, Colombia is the country with the second largest number of tree species on Earth, with approximately 6,000 species, as can be seen in

Figure 1 [

2].

Nevertheless, in 2021, 40% of the soils (45,379,058 hectares) exhibited some degree of degradation due to erosion, which affected the original vegetation cover, as presented in

Table 1 [

3].

This has resulted in 51.7% (58,964,543 hectares) of the Colombian territory being categorized as natural forest area [

4]. The distribution of this area within the continental area of Colombia’s regions is shown in

Table 2.

Deforestation in Colombia has remained within a range of between 120,000 and 220,000 hectares per year over the past decade, representing a significant contributor to the ongoing loss of forests. It is estimated that between 2000 and 2019, approximately 2.8 million hectares of forest were lost.

The causes of deforestation are listed, with consideration given to those identified by the IDEAM study [

1]. This approach allows for the identification of those causes that have a greater impact in terms of hectares of forest lost and the share of Colombia’s GDP. The resulting list includes 45.4 million hectares of degraded forest in the country.

The

agricultural frontier is defined as the boundary that separates the areas where agricultural activities are carried out from protected, special management and ecologically important areas [

5]. The area dedicated to livestock activity is approximately 34 million hectares, with a utilization rate of 0.6 hectares per head of cattle. This equates to 1.9% of the national GDP. Meanwhile, approximately 5 million hectares are utilized for agricultural purposes contributing to 5.5% of the national GDP [7].

Mining and quarrying (including oil and coal) would contribute approximately 5.5% of GDP, with 1.2 million hectares exploited, corresponding to 1.1% of the country’s continental land. The largest sub-sectors are dedicated to construction materials (57%) and, in second place, coal (17%) [

6].

The cultivation of illicit crops has occupied between 154,000 and 212,000 hectares. This equates to approximately 1.9% of GDP in 2019 [8].

On the other hand, a significant factor in forest management is the collective territories, which encompass approximately 53% of the country’s natural forests. Of these, 46% correspond to indigenous reserves, while 7.3% are located in the collective territories of Afro-Colombian communities [9].

As summary, following is a financial approach to land use and its productivity, based on aggregate data on the share of the Gross Domestic Product in Colombia and the information available to represent its main dimensions.

Table 3.

Financial land use.

Table 3.

Financial land use.

| Use |

Palm |

Coffee |

Cattle |

Agribusiness |

Mining and quarrying |

illicit crops |

| Area in millions (M) of hectares. |

0.6 M Ha |

0.85 M Ha |

34 M Ha |

5 M Ha |

1.2 M Ha |

0.18 M Ha |

| Productive contribution (GDP) in billions of dollars |

$ 2,5 B USD |

$2,2 B USD |

$4.3 B USD |

$12 B USD |

$12,3 B USD |

$6-$7 B USD |

| % Part. GDP* |

0.6% |

0.8% |

1.9% |

5.5% |

5.5% |

1.9% |

| The financial productivity per hectare in dollars.* |

$4,045 USD |

$3,064 USD |

$220 USD |

$4,352 USD |

$18,109 USD |

$38,545 USD |

Lately, in terms of carbon markets Colombia is among the top five countries in the world in terms of the development of forest carbon projects, as evidenced by the area covered and the number of certificates in the process of issuance and placement as could be seen on the Table 4. Nevertheless, the global market is still in its nascent stage, as it is still in the process of incubation within the financial capital markets. Its development is expected to coincide with the objectives of the United Nations for the years 2030 and 2050.

Table 4.

Carbon Markets Area and Carbon Offsets by country.

Table 4.

Carbon Markets Area and Carbon Offsets by country.

| Countries |

Area in hectares in certification process |

Carbon certificates |

| Brazil |

24,618,613 |

1,012,335,893 |

| Congo, the Democratic Republic of the |

21,307,376 |

1,016,889,078 |

| Colombia |

14,197,355 |

1,472,783,760 |

| Indonesia |

10,330,968 |

749,837,116 |

| Peru |

9,722,541 |

135,692,359 |

| China |

4,544,471 |

414,147,688 |

| Kenya |

2,979,668 |

168,147,233 |

| Zambia |

1,800,431 |

92,348,609 |

| Cameroon |

1,231,272 |

298,672 |

| Guatemala |

1,177,699 |

78,885,344 |

| Madagascar |

1,177,303 |

78,316,799 |

| Cambodia |

909,764 |

144,373,499 |

In light of the above, it has become evident that Colombia must prioritize the development of nature restoration and conservation activities as a key pillar in its pursuit of health and the expansion of productive land use. This is in accordance with the recommendations put forth by multilateral organizations and social capital authors, who have concluded that:

Social capital plays a pivotal role in the global response to climate change [

12].

The social and solidarity economy, through its enterprises, assumes a role in climate action in accordance with the sustainable development objectives [

13].

The most significant potential of the role of social capital lies in its capacity to facilitate the transition from vulnerability to climate adaptation [

14]. This can be achieved through the implementation of preventative measures that extend beyond those inherent to the exclusive management of emergencies and disasters.

In this context, contemporary studies of organizational frameworks have sought to understand the relationships between collective actions and institutions, as well as the interactions that norms and operating systems may have. Consequently, this study postulates a relation between the environmental initiatives of solidarity organizations and the principles of organizational design proposed by Elinor Ostrom [

15].

As previously stated, the methodology proposed by Elinor Ostrom in her book Governing the Commons demonstrates the significance of collective actions in terms of the longevity of these organizations, which has exceeded 100 years, and the extent to which they have developed the principles of organizational design, which has involved 10,000 to 15,000 people. This framework could serve as a foundation for the nascent efforts of the solidarity organizations Canapro Ambiental, Cooperación Verde and Cootregua, allowing us to identify potential avenues for deepening the solidarity and participatory activities of the organizations in environmental projects.

Finally, the results presented for this article reflects how Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) could address environmental and social problems [

16] led by the cooperative organizations beyond pecuniary motives (Corporate Social Responsibility).

2. Materials and Methods

In order to develop a methodology for collective actions, Elinor Ostrom’s proposal of grouping individuals who seek to achieve the benefits of collective action through reciprocal initiative was drawn upon. This entails individuals assuming a more prominent role than others in order to reinforce cooperation and thus prevent its erosion. Conversely, individuals and their governance are oriented towards the resolution of issues that emerge from collective actions.

The objective was to identify the formulation process applied in the environmental initiatives by the solidarity organizations Canapro Ambiental, Cooperación Verde and Cootregua. This was situated within the context of organizational governance, with a emphasis on the principles of organizational design put forth by Ostrom in his book, Governing the Commons. The objective was to identify the relationship between empirical evidence and subsequent theoretical validation (see Diagram 1 Theoretical Map 1).

Diagram 1.

Theoretical Map.

Diagram 1.

Theoretical Map.

Under the previous framework, the applicability principles for the analysis of the management of common-pool resources established by E. Ostrom were adopted. Under the set of situational variables that allow greater precision on the use of the methodology for empirical studies (See Table 5).

Table 5.

Situational variables.

Table 5.

Situational variables.

- 1.

Number of appropriators. |

- 2.

Size of the common-pool resource. |

- 3.

Temporal and spatial variability of common use resource units. |

- 4.

Current condition of the common pool resource. |

- 5.

Market conditions for the resource units. |

- 6.

Quantity and types of conflict. |

- 7.

Availability of information. |

- 8.

Status quo rules in use. |

- 9.

Proposed rules. |

Following the on-site in-depth interviews, the role of the solidarity organizations was identified in relation to a number of factors, including their context, environmental activities, administrative processes and internal and external governance systems. Subsequently, the frames of reference were generated in accordance with Ostrom’s principles of organizational design, and a categorical evaluation was conducted (see Matrix 1 and Matrix 2 at the end of the document).

2.1. Environmental Solidarity Initiatives

CANAPRO Environmental

The primary objective of the organization is to provide credit, educational and recreational activities, and tourism, with the purpose of meeting the expectations of its members. By 2022, the organization had approximately 53,000 members and a credit placement of approximately $40 million dollars per year, with assets amounting to $150 million dollars. Its governance structure comprises the Assembly of Delegates (comprising over 100 representatives), the Board of Directors (comprising nine members), the Supervisory Board (comprising three principal members), the Board of Directors (comprising one manager, 19 area directors and two rectors), and seven administrative committees.

In 2008, the CANAPRO Cooperative initiated its environmental project with the acquisition of approximately 7,000 hectares in the municipality of Puerto Carreño in the department of Vichada. The designated land was to be utilized for a variety of purposes, including tourism, education, the protection of water sources, reforestation, beekeeping and the transition to renewable energy. The achievement of the issuance of nearly 18,000 carbon credits and the implementation of product development projects based on beekeeping, cashew and reforestation plans in favor of biodiversity. The company’s involvement in projects aimed at the conservation of the tapir, the butterfly tiger, the puma and the sustainability of the Ramsar and Bita river habitats is worthy of note. By the end of 2023, the company had employed approximately 30 individuals, comprising administrative staff and operational personnel. This represented the commercial and social presence in one of the most remote territories in the country, despite its strategic geographical location, acting as a gateway to the Amazon and a border region with Venezuela and Brazil.

CANAPRO Ambiental has been able to generate and accumulate experience in training and developing personnel suitable for productive activities in the country by being certified by the State through the Colombian Agricultural Institute ICA. This has enabled the company to draw upon its experience of planting timber and native species to formulate and implement projects based on cashew, including the stages of selection, baking and packaging. The company has been able to generate value-added alternatives in rural areas of the country.

Ultimately, they established credit operations in urban areas and positioned themselves as a solidarity option in the regions by spearheading environmental initiatives that had previously been undertaken by private companies and non-profit organizations.

2.2. Cooperación Verde

The Cooperación Verde initiative was established by 25 solidarity organizations with the objective of promoting the sustainable development programme for the social and solidarity economy. In order to achieve this objective, in 2009 the private company Cooperación Verde was established through the collective contributions of the participating organizations. The objective was to promote environmental projects at the regional level and to purchase nearly 5,000 hectares in the area of the municipality of Puerto Gaitán in the Department of Meta

The project has resulted in the planting of two million trees and the restoration of two thousand hectares, thereby facilitating the production of sustainable timber, biomass for energy generation, and developments in beekeeping and ecotourism. Moreover, they have maintained employability levels of between 30 and 100 individuals, in accordance with the requirements of the projects. This has entailed the mechanization of processes on a large scale, access to financing from the conventional financial system, and the sale of forestry and carbon certificates for approximately one million dollars. The company has employed the resources obtained to diversify its product range, including the production of triplex sheets and chipboard, with the objective of serving both domestic consumption and multinational clients.

By 2023, the Green Cooperation patrimony had grown to encompass 65 organizations operating within the social and solidarity economy. These organizations have received considerable recognition, including being identified as one of the 500 most outstanding green Latin American initiatives and being awarded the BIBO accolade in the category of sustainable landscape construction. The latter award was sponsored by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and involved juries from the Humboldt Institute and the Amazon Research Institute. Moreover, the organization has been lauded for its contributions to the social reintegration of individuals affected by the armed conflict in Colombia, as well as its engagement with indigenous communities, in particular the Sikuani Indians.

In terms of governance, the Annual Assembly of Members is attended by the general directors of the solidarity organizations, while delegates are appointed for the monthly meetings of the Board of Directors, which are attended by the auditors and managers. The rotation of representatives occurs on a biennial basis.

Finally, Cooperation Verde has been acknowledged as a pioneer in the field of private enterprise financed by solidarity capital, which has enabled it to participate in market opportunities and spearhead social and reconciliation processes in the region. It is anticipated that investment of between 10 and 20 million dollars will be made in future expansion projects, which will encompass an additional 10,000 hectares and the development of collaborative initiatives with indigenous communities in collective territories.

2.3. Cootregua

Cootregua was established in 1988 by a group of education employees in Inírida, in the department of Guainía, under the guidance of Father Antonio Bayter. The initiative was spearheaded by Mrs. Maria Isbelia Gutiérrez and has been managed by a Board of Directors since its inception. Over the past three decades, the organization has facilitated the growth of its assets through the utilization of credit facilities based on the savings of its associates. By 2023, the accumulated assets of Cootregua had reached 25 billion pesos, with 40 employees and 11,000 associates. In its early days, Cootregua’s social activities were primarily focused on supporting microenterprises, training the local population, and promoting sports activities. Subsequently, the scope of activities was broadened to encompass Cootregua’s tutoring services on entrepreneurship, finance, and administrative management for students and associates. Mrs. Maria Isbelia Gutiérrez has continued to serve as the principal figure in the provision of financial education within the municipality. She has provided assistance to the local population at each stage of their life projects, as well as offering personalized guidance to clients. Her work is notable for its success in overcoming the challenges posed by the distances and limited communication channels available to the population, which rely primarily on river transportation and satellite internet access.

Cootregua has played a pivotal role in the processes of social marginalization experienced by the population displaced by the internal conflict, as well as in the prioritization of women’s empowerment. The objective of Cootregua is to enhance the quality of life of its inhabitants, with a focus on the pillars of the family, the home, and the generation of employment. Cootregua’s focus on the indigenous population has been of great significance for the Puinave and Kurripaco ethnic groups. Moreover, it has enabled the provision of financial services to local entrepreneurs and beneficiaries of carbon certificates in the region.

This has enabled Cootregua to act as a catalyst for social inclusion processes for those populations that are the furthest removed from the formal economy. Furthermore, it has improved the quality of life for the local population and facilitated the development of environmental initiatives in the region.

3. Results

The proposed methodology involved the construction of Matrix 1 and Matrix 2, which were derived from Ostrom’s organizational design principles. Subsequently, the matrices were employed to analyze the components identified in the field study.

Clear limits and membership: the financial statements and reports of the directors for the organizations under the study provided unambiguous information regarding the number and contribution of associates participating in the organizations. In accordance with the specific regulatory framework that governs the activities of solidarity organizations in Colombia, there are established mechanisms for the designation and legal constitution of such entities. These mechanisms are designed to guarantee the acknowledgement of those engaged in cooperative activities as contributors.

The regulations are congruent in that solidarity organizations are part of the country’s consolidated organizational ecosystem. These include oversight, financial, strategic and educational committees, among others, which facilitate the active participation of the delegates (representatives of the members) at each level of the organization. Furthermore, the bylaws are aligned with international cooperative principles, considering multilateral regulatory trends and applying them to local contexts. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the regulations remain generic and broad during the review process. This raises the question of whether they could be made more specific regarding the role of the solidarity function with respect to environmental and social issues. However, it is understandable that these issues are still in the development phase of a global framework.

The organizations under study exhibited a pronounced tendency towards collective decision-making, accompanied by a pronounced sense of organizational identity and a high level of attention to both internal and external control bodies. These factors serve to reinforce the identity of the cooperative and solidarity sector in Colombia, despite the geographical distances between its various locations. It was observed that respect for the principles of the sector is upheld at all levels of organizational structure. Furthermore, the directors of these organizations demonstrated a clear commitment to the boards of directors that oversee them, as well as to maintaining a comprehensive reporting system to their delegates and associates, through both public and internal communications.

Oversight. The organizations under study are part of the social and solidarity economy ecosystem, which is overseen by the Superintendence of the Solidarity Economy. This body is responsible for monitoring and regulating activities within the ecosystem, and its performance is recognized, as are the regulations that it issues. In addition, at the internal level, there are several control bodies that seek to update regulations and participate in the dialogue with public policy agents such as the National Planning Department and the National Learning Service, among others. It is also noteworthy that, in the context of interdisciplinary activities, the organizations in question have demonstrated compliance with local environmental regulations. This has been evidenced by their engagement with Regional Autonomous Corporations and representatives of the Ministry of the Environment.

Gradual sanctions: It was not possible to identify any clear or standardized mechanisms for the management of this principle. Nevertheless, it was evident that managers were prompt in making necessary adjustments to their actions, particularly since performance evaluations had a bearing on hiring decisions and the activities they undertook.

Conflict resolution mechanisms: each of the organizations maintains open channels of communication between associates, delegates and officials, which are regular and open. In these spaces there is dialogue and a record of events associated with internal and external conflicts; however, it was not possible to clearly identify the management of the consequences or effects of these situations. Indicating the need to establish a program for the follow-up and closure of these processes, which would allow the control bodies to have a report on the management carried out by the organization, as well as the potential input it could have for the management in case of similar events.

Recognition of the right to association: Given the condition of the organizations studied, which are part of the Social and Solidarity Economy ecosystem, the right to association is part of the international cooperative principles, and therefore is an intrinsic part of the activities and organizational foundations.

Ecosystemic company: each of the organizations studied is part of the regional ecosystem. The leadership role of Cootregua in the development of financial inclusion in the municipalities where it operates was clearly identified, which has allowed it to remain as a benchmark for banking in the Amazon and its participation in the active dialogue with the indigenous communities of the territory. Similarly, CANAPRO environmental has continued to play an active role in public and private bodies, as evidenced by its partnership with three other private organizations to achieve carbon certifications. Finally, Cooperación Verde is distinguished by its leadership in social inclusion processes. It has successfully integrated victims of the conflict and displaced populations into its workspaces, providing them with the opportunity to pursue their life projects in the rural context, which is one of the most challenging environments in the eastern plains region due to land restitution processes and illegal activities. Despite budgetary limitations in terms of financial and human capital, the organizations actively participate in their ecosystems.

Matrix 1.

Ostrom’s organizational design principles.

Matrix 1.

Ostrom’s organizational design principles.

| Coop Organization |

Clear boundaries and membership |

Consistent regulations |

Spaces for collective decision making |

Oversight |

Gradual sanctions |

Conflict resolution mechanisms |

Recognition of the right of association |

Ecosystem company |

| CANAPRO ambiental |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Cooperación Verde |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Cootregua |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Matrix 2.

Situational variables E. Ostrom.

Matrix 2.

Situational variables E. Ostrom.

| Evaluation of the benefits of an institutional choice |

|---|

| Situational variables E. Ostrom |

Canapro Ambiental |

Cooperación Verde |

Cootregua |

-

1.

Number of appropriators. |

55,000 associates |

65 coop organizations |

11,000 associates |

-

2.

Size of the common use resource. |

7,000 hectares |

5,000 hectares |

Townships: 6 offices at Guaviare and 2 at Guainía |

-

3.

Temporal and spatial variability of common-pool resource units. |

Fixed extensions

Employees 30-100 |

Fixed extensions

Employees 50-100 |

Flexible locations.

40 employees |

-

4.

Current condition of the common-pool resource. |

Stable growth. |

Stable growth. |

Growing. |

-

5.

Market conditions for resource units. |

Free market economies and democratic institutions. Frontier economies. |

Free market economies and democratic institutions. |

Free market economies and democratic institutions. Frontier economies. |

-

6.

Number and types of conflicts. |

Border region with Venezuela. |

Oil region in the process of adapting to post-conflict. |

Venezuela and Brazil border region. |

-

7.

Availability of information. |

Large and sufficient. |

Large and sufficient. |

Large and sufficient. |

-

8.

Status quo rules in use. |

Cooperative Regulations |

Private Company Regulations |

Cooperative Regulations |

-

9.

Proposed rules. |

Operational expansion in properties. |

Expansion in extension and target population. |

Expansion in regional offices. |

4. Discussion

With regard to the limitations of the study, it is essential to note that a greater number of organizations that are interrelated with respect to those that were the object of the study must be accessed. This could facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of organizational dynamics at the external level, thereby enabling the identification of potential weaknesses in the area of governance. The present study was limited to the examination of internal personnel, associates, and delegates.

Similarly, it would be advantageous to establish a classification system for the degree of rigour in the application of Ostrom’s principles of organizational design. However, this was not feasible due to the scale and resources of the present study, which was conducted in an exploratory setting. It is thus recommended that further investigation be conducted into each of the design principles, with the objective of increasing the number of organizations involved.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that, despite the satisfactory nature of the evidence presented in this exploratory study, it is necessary to formulate a methodology that explicitly addresses environmental issues in the future as well as the potential of Corporate Social Responsibility elements for a better performance. This is despite the theoretical uncertainty that exists in the academic literature.

5. Conclusions

The principles of organizational design proposed by Ostrom are consistent with the environmental activities of the solidarity organizations Canapro Ambiental, Cooperación Verde and Cootregua.

It is possible to identify potential areas for improvement in the organizations with regard to conflict resolution mechanisms and gradual sanctions. It is recommended that collective decision-making spaces be employed in order to establish explicit governance on these principles of organizational design.

The aim of this study is to demonstrate the applicability of Elinor Ostrom’s principles of organizational design to the academic community, thereby providing a basis for the validation of the development of organizations that are the product of collective action. This is exemplified by the social and solidarity economy sector enterprises described above.

It is important to note that solidarity organizations in environmental initiatives could maintain their role as a catalyst between the private and public sectors. This would make up the critical mass required for the establishment of organizational ecosystems based on Elinor Ostrom’s design principles and founded on Corporate Social Responsibility elements like: supervisor commitment to ethics, equity sensitivity of managers, individual employee discretion and salience of issues to employees [18].

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process. During the preparation of this work, the authors used the DeepL Translator, Curie, and DeepL Write to improve language and readability. After using those services, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article. This work was supported by Pontifical Xaverian University.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Faculty of Environment and Rural Studies and the Institutional and Rural Development Research Team for providing the environment and tools to produce this document.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Armenteras, D., González, TM., Meza, M., Ramírez-Delgado, J.P., Cabrera, E., Galindo, G., Yepes, A. (Eds). 2018. Causas de Degradación Forestal en Colombia: una primera aproximación. Universidad Nacional de Colombia Sede Bogotá, Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales de Colombia-IDEAM, Programa ONU-REDD. Bogotá D.C., Colombia., 105 pág.

- FAO and UNEP. 2020. The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people. Rome. [CrossRef]

- DEGRADACION DEL SUELO - IDEAM. (n.d.). Retrieved June 26, 2024. Available online: http://www.siac.gov.co/degradacion-del-suelo.

- Sexto Boletín de Alertas Tempranas de Deforestación. IDEAM Bulletin 06. 2015.

- Departamento Nacional de Planeación. (2020). CONPES 4021 Política nacional para el control de la deforestación y la gestión sostenible de los bosques Bogota, Colombia.

- Así es nuestra Colombia minera | Agencia Nacional de Minería ANM. (n.d.). Retrieved June 26, 2024. Available online: https://www.anm.gov.co/?q=Asi-es-nuestra-Colombia-minera.

- Solo se está aprovechando 13,5% de las 39,2 millones de hectáreas con potencial. Retrieved June 26, 2024. Available online: https://www.larepublica.co/economia/del-34-del-area-potencial-para-cultivar-en-colombia-se-aprovecha-cerca-del-13-5-3391297#:~:text=Colombia%20cuenta%20con%20una%20extensi%C3%B3n,13%2C5%25%20del%20potencial.

- Narcotráfico pesa hasta $19 billones en el Producto Interno Bruto de Colombia. Retrieved June 26, 2024. Available online: https://www.larepublica.co/economia/narcotrafico-pesa-hasta-19-billones-en-el-producto-interno-bruto-de-colombia-2933774.

- García, A.P.; Yepes, A.P.; Rodríguez, M.; Leguía, D.; Ome, E.; Reyes, L. Informe Final “Logros, Aprendizajes y Retos”. Programa ONU-REDD Colombia. Bogotá D.C. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- DANE 2024. Producto Interno Bruto Trimestral (CT) desde el enfoque de la producción a precios corrientes. DANE - PIB Información técnica. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/cuentas-nacionales/cuentas-nacionales-trimestrales/pib-informacion-tecnica (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Atmadja, S.; Komalasari, M.; Alusiola, R.; Barboza, I.; Sartika, L.; Theresia, V.; Simonet, G. 2023. The International Database on REDD+ projects and programs Linking Economics, Carbon and Communities (ID-RECCO) - Project tables, V.5.

- IPCC. (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C. In Ipcc - Sr15 (Vol. 2, Issue October).

- Alarcón Conde, M. Á., & Rodríguez, J. F. Á. (2020). El Balance Social y las relaciones entre los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible y los Principios Cooperativos mediante un Análisis de Redes Sociales. CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa, 99. [CrossRef]

- Szreter, S., & Woolcock, M. (2004). Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. In International Journal of Epidemiology (Vol. 33, Issue 4). [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. (2015). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. In Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. [CrossRef]

- Auld, G., Bernstein, S., & Cashore, B. (2008). The new corporate social responsibility. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 33. [CrossRef]

- Hong, H., & Shore, E. (2023). Corporate Social Responsibility. In Annual Review of Financial Economics (Vol. 15, pp. 327–350). Annual Reviews Inc. [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).