3.1. Determination of Grindability

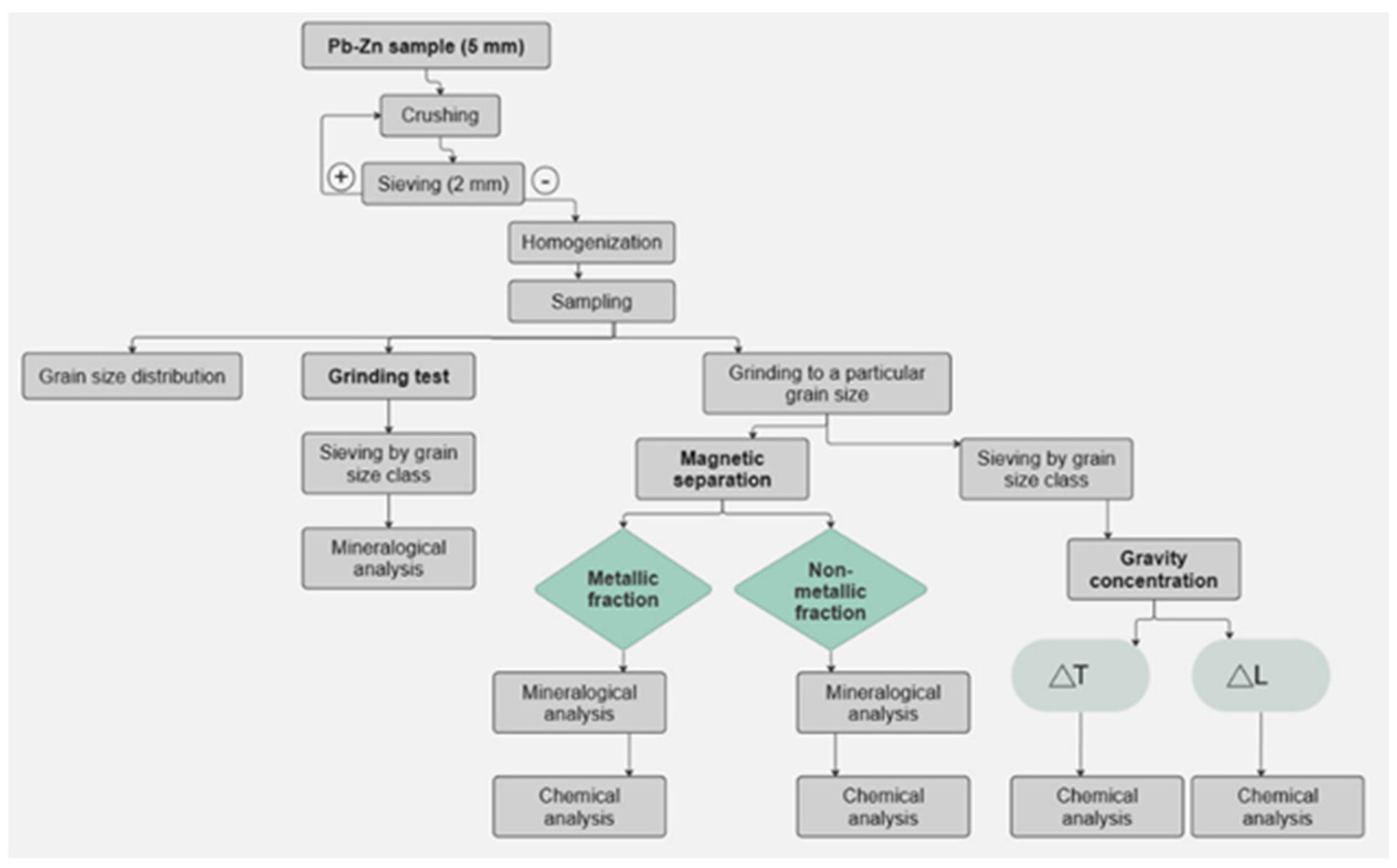

A grindability test was employed to identify the conditions (grinding time and grain size class) for separating useful components in Pb-Zn slag from inert or hazardous ones. The mechanical processing of slag and other similar technogenic raw materials containing a certain percentage of nonferrous metals is a field lacking in technological know-how and experience. The experiment was conceptualized based on previous experience in grinding hard metallic ores with high aluminosilicate concentrations. Wet grinding was used for a variety of reasons: 1) it complements the subsequent concentration procedures (wet magnetic separation and wet gravity concentration), and 2) it is up to four times more efficient than dry grinding (uses less energy for the same grinding action).

Pb-Zn slag contains valuable minerals (wurtzite, sphalerite, galena, cerussite, akermanite, wüstite, monticellite, franklinite, and zincite [

37]) corresponding to metal alloys present in the form of complex intergrowths. The amorphous phase (glassy tailings) of aluminosilicates, silicates, spinel, and mixed spinel-silicate composition, as previously assumed, is the predominant phase in observed slag samples [

37]). The amorphous phase is responsible for the extremely high hardness of Pb-Zn slag. Upon grinding (short grinding periods), non-metallic mineral phases (crushed parts of the glassy matrix) are expected to appear in oversize classes (a residue on a sieve). Metal minerals are the “softer” part of the slag’s complex composition; therefore, they are expected to be in undersize classes.

The initial sieve test design (ES-1) included the following projected sieve openings: (1) sieve with a 0.15 mm opening to separate coarser grain sizes (+0.15 mm) with no useful components (i.e., crushed glassy phase, i.e., tailings); (2) sieves with 0.15 mm and 0.1 mm openings to conduct “pre-concentration” of useful minerals (softer metal minerals and/or their complex intergrowths) in the -0.15+0.1 mm grain size class. Initial testing on the starting raw material revealed that the release limit of viable components begins with classes of approximately 0.1 mm; and (3) sieve with 0.025 mm opening to separate the -0.025+0.00 mm class to determine if metallic components (lead-copper and zinc-copper intergrowths) have transitioned into the finest class while grinding.

The purpose of these tests was to detect the grain size classes in which non-useful tailings are concentrated so they could be eliminated from further processing in order to decrease energy consumption during milling. Furthermore, detection of the exact particle size of metallic components is important, so their migration into the fine-size class is prevented because concentrating them at that point becomes challenging.

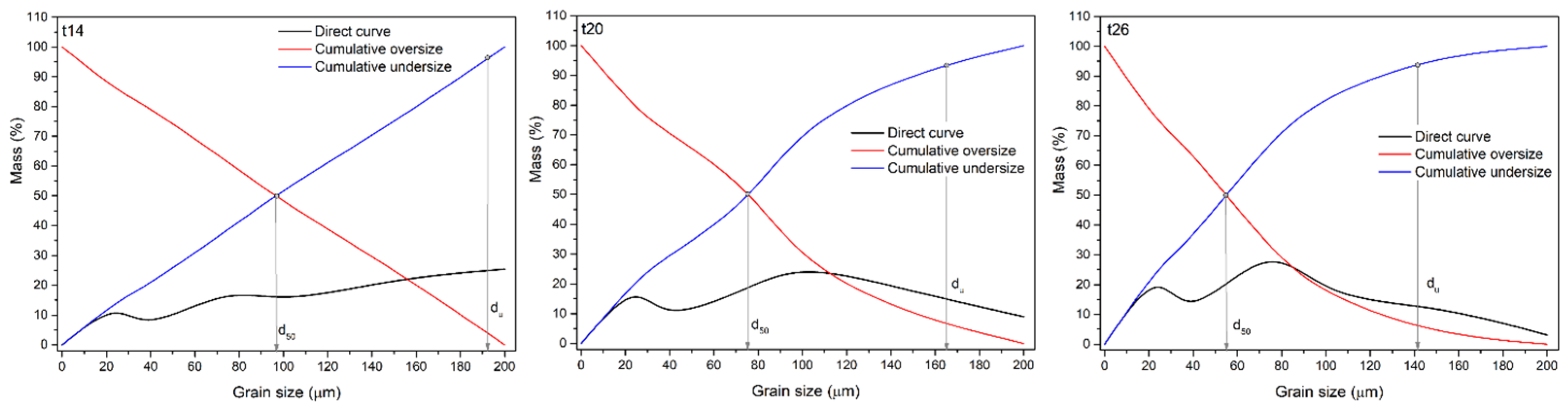

Figure 4 shows grain size distribution diagrams for ES-1 for intervals (t) of 14, 20, and 26 min (i.e, GT-1, GT-2, and GT-3).

As shown in the graphs (

Figure 4), longer grinding periods resulted in a material with a smaller mean grain diameter (d

50) and upper grain limit (d

u): t=14 min, d

50=97.5 µm, d

u = 193.3 µm; t=20 min, d

50=76.3 µm, d

u=165.7 µm; and t=26 min, d

50=55.7 µm, d

u=142.5 µm.

In the first GT (t = 14 min), mineralogical analysis revealed that the coarsest grain class (+0.15 mm) contained fused vitreous phase and metal alloy grains. Analysis was conducted by visual examination of the grain mixture obtained as oversize on a 0.15 mm sieve. The sample was observed by an optical microscope (described in

Section 2.7). This class accounts for 25.41% of the overall micronized product in GT-1. Conglomerates and intergrowths were found in the -0.15+0.1 mm class. In the finest grain size class (-0.025+0.0 mm) of the slag sample, alloy grains and tailings were indistinguishable. The finest class accounted for 14.83% of the total mass used in the GT-1.

With an extended grinding in the second GT (t=20 min), mineralogical analysis revealed, same as in the GT-1, that the coarsest class (+0.15 mm) is composed of fused glassy phases and metal alloy grains. The fused inclusions and intergrowths were also evident in the finer class (- 0.15+0.1 mm). The number of free alloy grains increased. In the finest class (-0.025+0.0 mm), alloy grains were found to glow under the microscope’s reflected light (i.e., they are distinguishable). A longer grinding period of 20 minutes resulted in a higher mass share of the lowest grain size class (21.39%), which is roughly 6.5% higher than GT-1.

In the third GT (t = 26 min), the mineralogical analysis revealed that the coarsest grain size class (+0.15 mm) contains fused glassy phases and metal alloy grains, as well as very large free metal alloy grains. The share of the +0.15 mm class in the total micronized product is rather small (3.06%). The middle class (-0.15+0.1 mm) consisted of more free alloy grains than fused grains. Alloy particles were identifiable in the -0.025+0.0 mm class. The grinding period of 26 minutes produced the highest mass share of the finest grain size class, its participation in the GT-3 being 26.98%. That is a mass increase of approximately 5.6% over the GT-2 and 12.15% over the GT-1. The obtained results of the mineralogical analysis of the GT-3 show that the coarse class (+0.15 mm), despite its small mass share of 3.06% in the total amount of micronized product, cannot be rejected as the class in which tailings are concentrated solely due to the presence of large alloy grains.

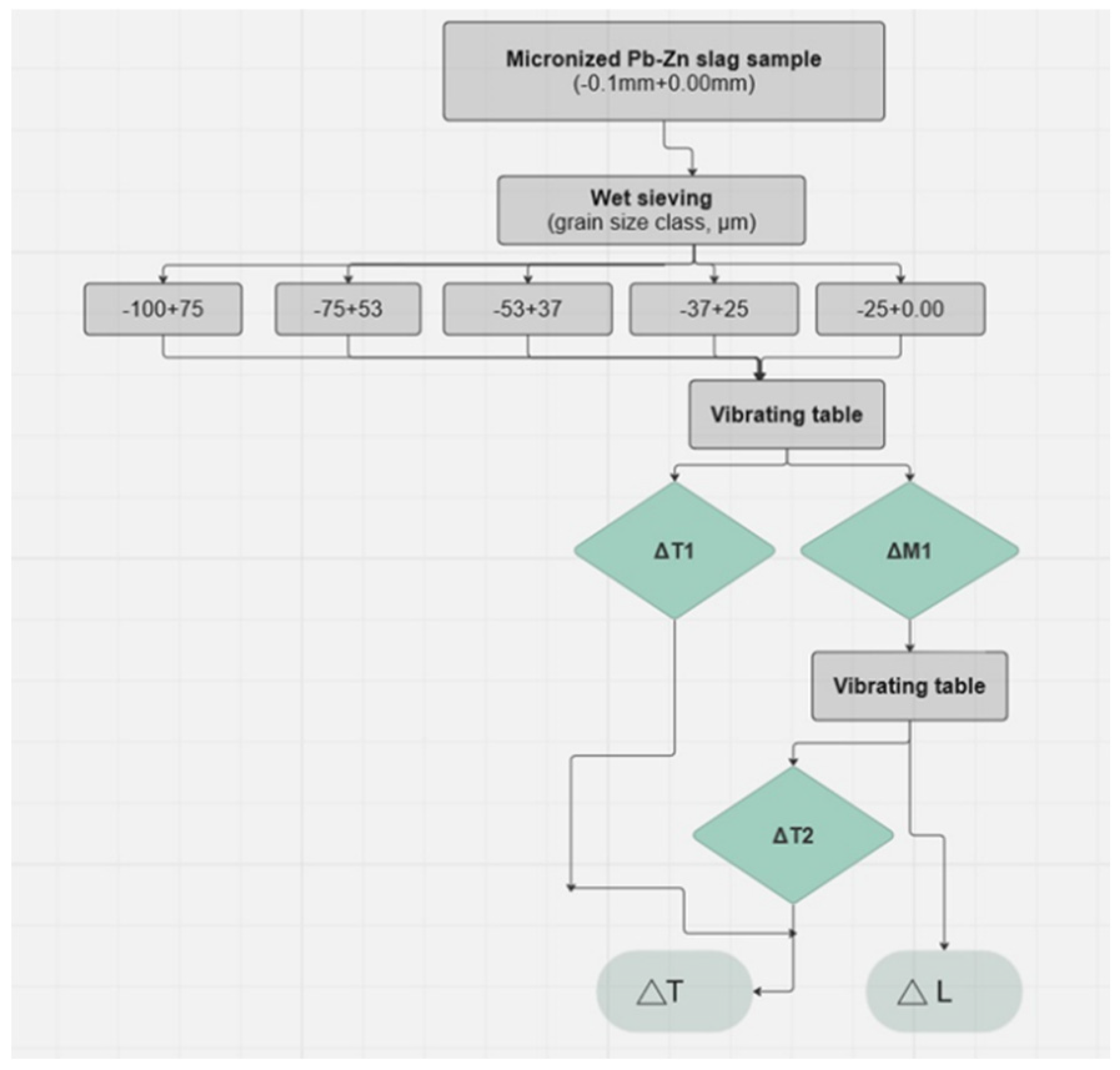

The second sieve test design (ES-2) included the following projected sieve openings: i.e., grain size classes: -0.10+0.075 mm; -0.075+0.053 mm; -0.053+0.037 mm; -0.037+0.025 mm; and -0.025+0.00 mm.

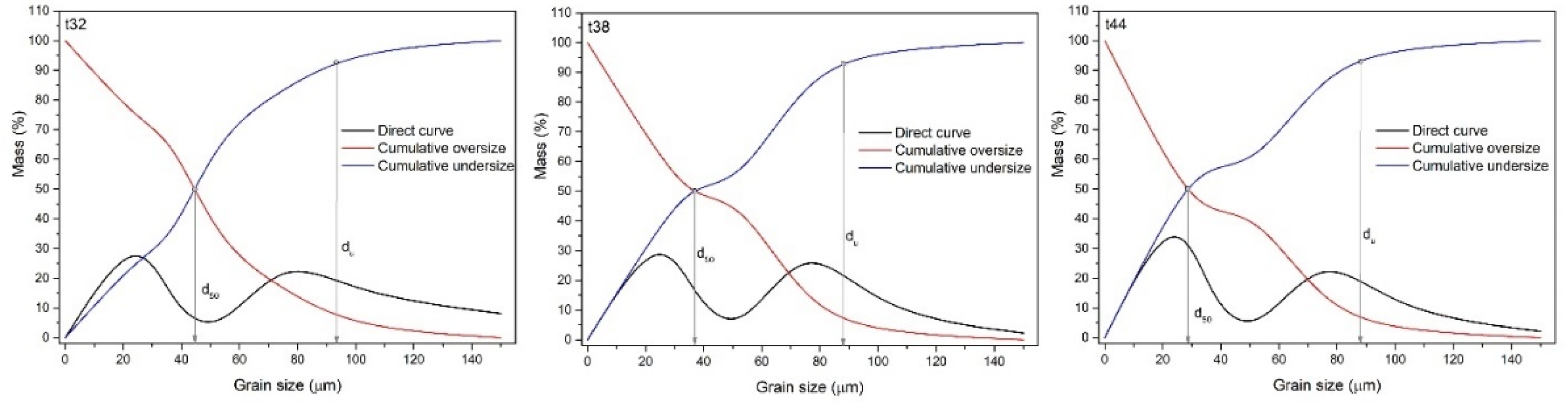

Figure 5 shows grain size distribution diagrams for ES-2 intervals (t) of 32, 38, and 44 min (i.e., GT-4, GT-5, and GT-6). These GTs did not contain a +0.15 mm grain size class as a result of the extended milling. The coarsest grain size class found in these samples was -0.15 + 0.1 mm.

Grinding for a longer period reduced the mean grain diameter (d

50) and upper grain limit (d

u) of the treated Pb-Zn slag (

Figure 5): t=32 min, d

50=44.2 µm, d

u = 93.4 µm; t=38 min, d

50=37.2 µm, d

u=89.1 µm; and t=44 min, d

50=28.9 µm, d

u=87.2 µm.

In the GT-4 (t = 32 min), the -0.15+0.1 mm class accounted for only 8.12% of the total mass. This class contains fewer coalescing alloys and less amorphous phases, as well as more free alloy grains. The rest of the observed classes (-0.10+0.075 mm; -0.075+0.053 mm; -0.053+0.037 mm; -0.037+0.025 mm; and -0.025+0.00 mm) comprised free alloy grains, vitreous phase, and silicates. The finest class (-0.025+0.00 mm) contained small metal grains up to 10 μm in size. Although the Pb-Zn slag sample was ground for 32 min, there are free alloy grains and a small amount of coalesced mineral grains in the coarsest class (0.15–0.1 mm); therefore, this class cannot be rejected as a class in which tailings are concentrated. The mass percentage of the finest class (-0.025 + 0.00 mm) increased to 38.45%, which is an 11.47% increase over the GT-3 (t = 26 min).

The coarsest class (-0.15+0.1 mm) accounted for only 2.22% of the total mass after the GT-5 (t = 38 min). There were more free alloy grains, a few alloy fusions, and amorphous phases in this class. All other classes contained free alloy grains, a glassy phase, and silicates. Spinel was found in the -0.053+0.037 mm class. It was in needle-like form, sizing up to 150 μm in length and 30-35 μm in width. This might be the outcome of the slag grains breaking into long, needle-like shapes due to the mechanical crushing [

48,

49]. The -0.025+0.00 mm class contained a considerable number of metal grains, about 10 μm in size. Even with the extra grinding (38 minutes total), the mass percentage of this class in the entire mass increased only marginally to 38.96%. This shows a slight increase of 0.51% over the GT-4, when the mass share of the finest class was 38.45%.

Even though the mass share of the coarsest class (-0.15+0.1 mm) was only 2.12% in the GT-6 (t = 44 min), free alloy grains and silicates were still present. The analyzed grain size classes in the GT-6 were identical to the two previous GTs. Free alloy grains, the glassy phase, and silicates were found in all classes. As in the previous test, a needle-shaped spinel was found in the -0.053+0.037 mm class. Very fine metal grains were found in the -0.025+0.00 mm class. This class’s mass participation ascended to 48.20% as the grinding time increased (t = 44 min), which is a 9.24% increase from the GT-5.

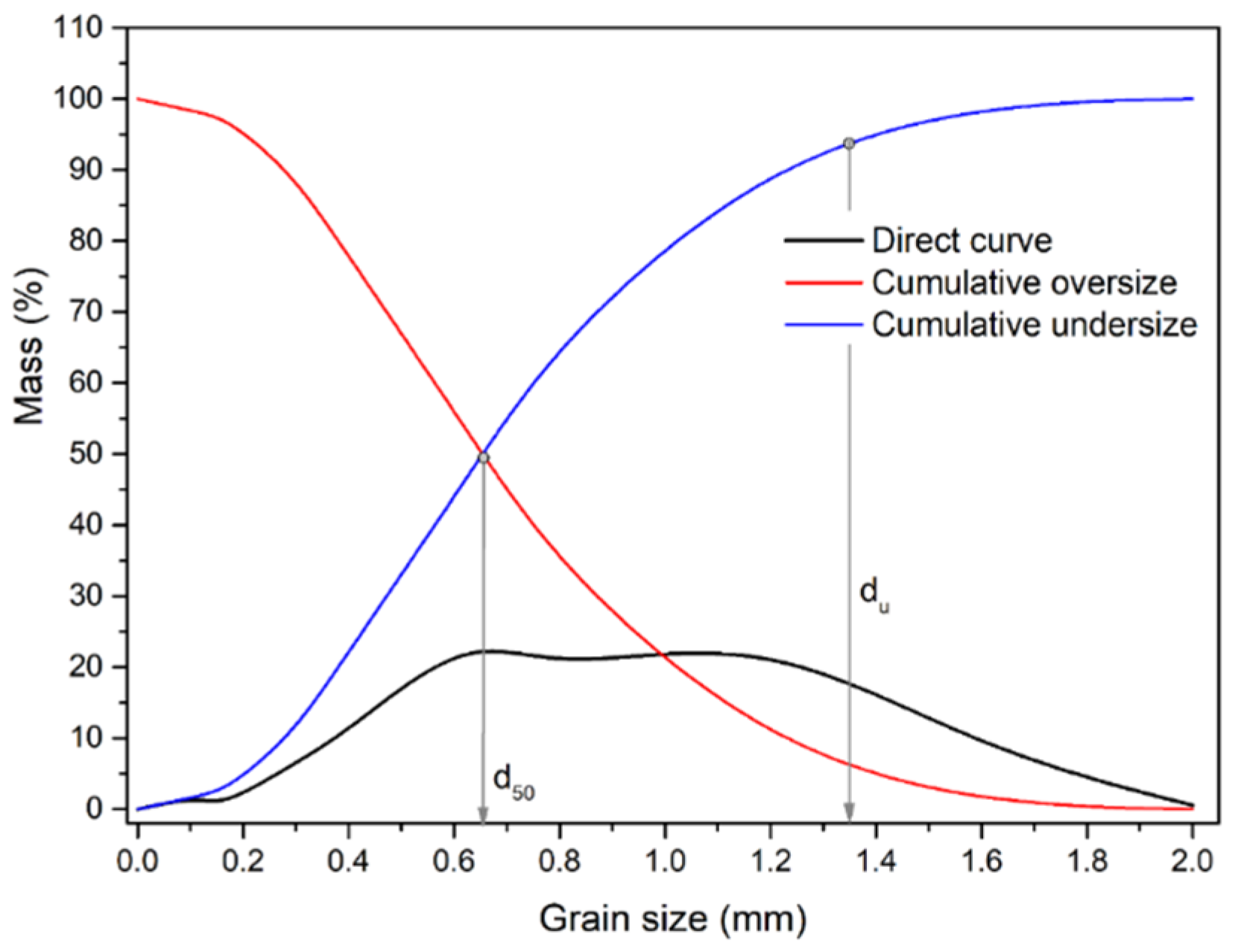

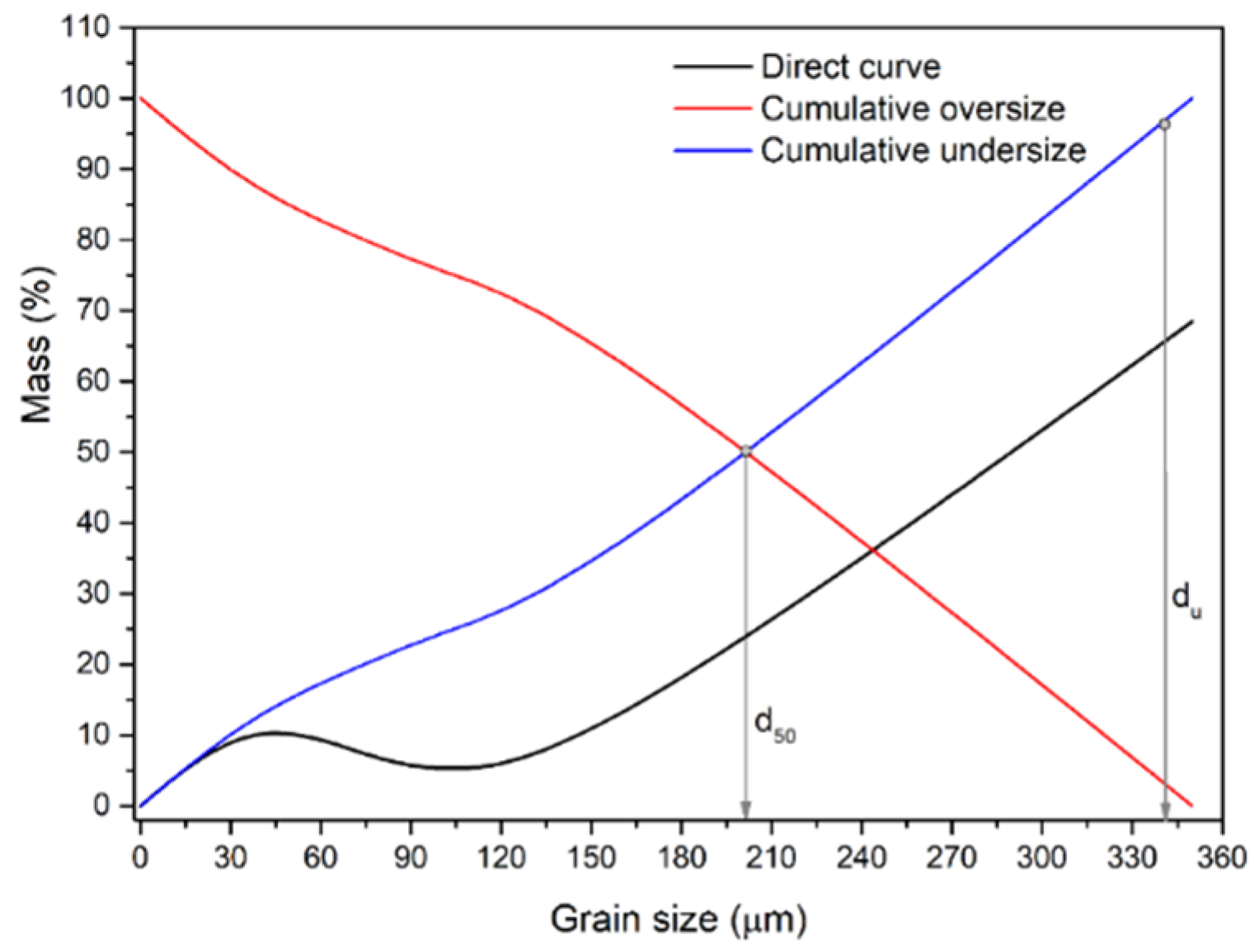

Figure 6. shows the grain size distribution of the Pb-Zn slag grain mixture obtained after dry grinding for 20 minutes. The dry-grinded mixture had a mean grain diameter of 206.1 µm and an upper grain size of 335.2 µm. Thus, wet grinding (t = 20 min) with the same energy and time input outperformed dry grinding of the identical material.

The GT1-3 results indicate that no test, not even with the shortest or longest grinding duration, can exclude the coarsest class (+0.15 mm), in which tailings were expected to be concentrated. The mineralogical study of this class revealed free alloy grains and fusions of glassy phase and alloys; therefore, it cannot be described as a tailings-concentrated class. The coarsest class in the GT4-6 was -0.15+0.10 mm, which also could not be excluded from GTs as a class that contains concentrated tailings solely. Namely, this class contained grains of metal alloys and conglomerates; hence, eliminating it would result in a loss in metal utilizability.

Furthermore, the GT results demonstrated that the Pb-Zn slag does not behave like ore and that the metal grains do not crush easily, despite being known to be softer than both the glassy phase and the silicates. Extended grinding from GT-2 to GT-6 (20–44 min) raised the metal content and the finest class (-0.025+0.00 mm) content. The finest class had a significant mass share, which could make the metal concentration procedure difficult. The presence of large metal grains in the coarsest class is very uncommon, especially lead grains, considering the mechanical characteristics and relative softness of lead. Large metal grains may make grinding more challenging since they have a propensity to collide with one another and the balls in the mill during grinding. The outcome is an increase in grain size rather than a decrease in size.

The GTs supplied fundamental information on the grinding process and the release of usable components from Pb-Zn slag. It was determined that most of the free utilizable components are present in the -0.1+0.00 mm class. Therefore, this class was further used in magnetic separation and gravity concentration tests, which are methods for successfully separating nonferrous metal alloys and minerals into one product while separating tailings into another.

3.2. Magnetic Separation of Pb-Zn Slag

After GTs, the Pb-Zn slag was subjected to a magnetic separation test to further reduce inefficient components. MS removes iron-containing magnetic components from the sample and is expected to result in final products (concentrates) with a higher metal content (relative to the input) and thereby improved utilizability. “Wet” and “dry” separation procedures were tested on a Pb-Zn slag sample of -0.1+0.00 mm grain size.

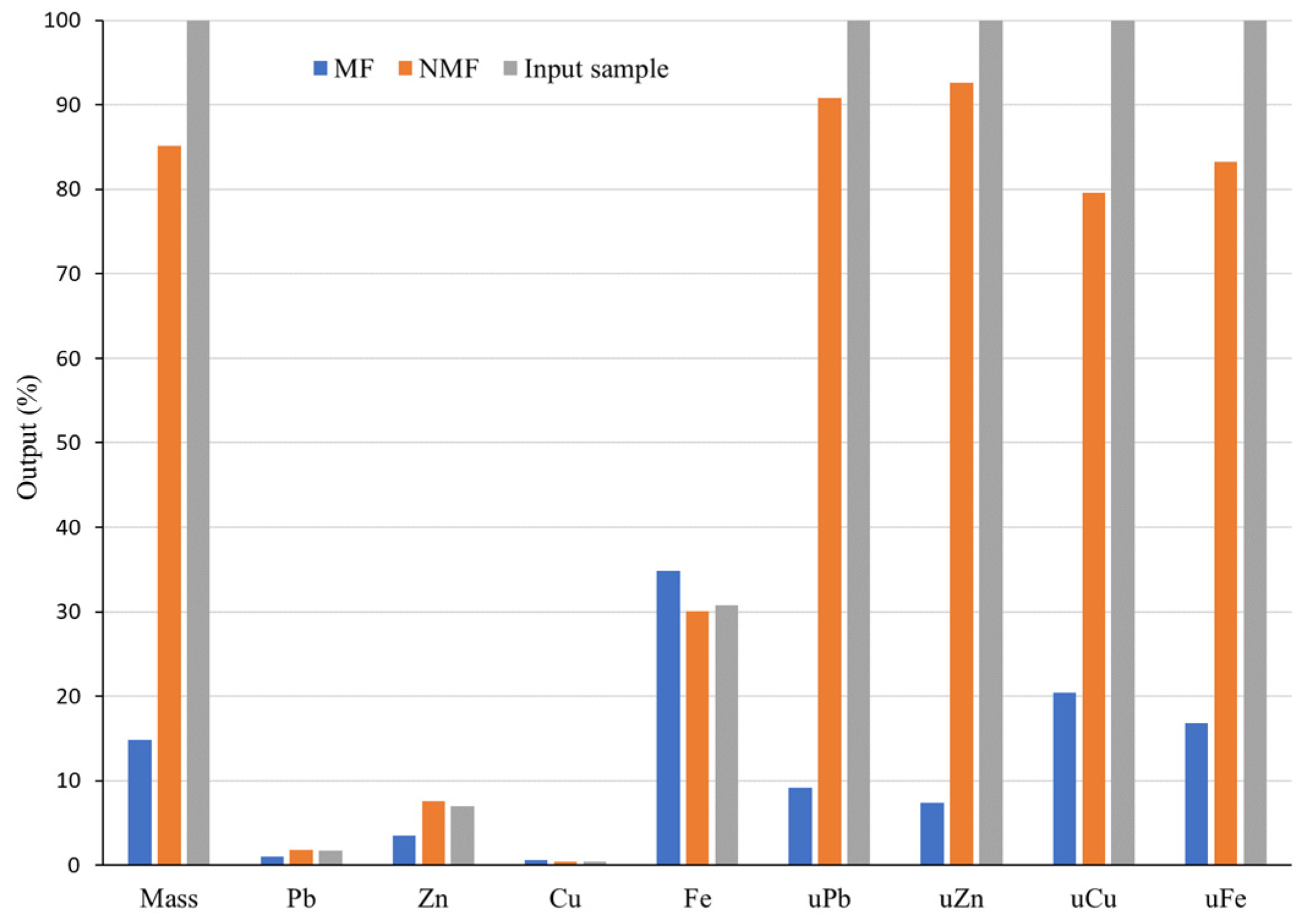

3.2.1. Magnetic Separation of Pb-Zn Slag by Davis Separator

The Pb-Zn slag magnetic separation experiment was conducted using a Davis separator, which divided the sample into its magnetic fraction (MF) and non-magnetic fraction (NMF). Both fractions were dried and subjected to chemical analysis via AAS. The results are reported in the form of a material balance in

Figure 7.

The analysis of the results of MS performed on the Davis separator revealed that the MF and NMF were not adequately separated. The MF accounted for 14.81% and the NMF 85.19% of the total treated mass. A considerable amount of nonferrous metals that have been separated by applying a low magnetic field are present in the MF: 1.03% lead, 3.48% zinc, and 0.62% copper (

Figure 7). The amount of Cu in MF is 38% higher than that of the input (0.45%). Non-ferrous metals are known to be non-magnetic; therefore, their presence in the MF is uncommon, especially if a low magnetic field is employed for separation, which should only separate strongly magnetic components. The reason for the presence of Zn in the MF could be the mineral franklinite (ZnFe

2O

4). Theoretically, franklinite is composed of 16.59% Zn and 37.78% Fe [

50]. Thereby, the presence of Zn in the MF can be explained either by its association with franklinite, or amorphous formations in the slag that are chemically similar to franklinite. However, this explanation is not feasible for Pb or Cu.

Due to the small mass share of the MF (14.81%), the utilizability (marked with “u” in

Figure 7) of non-ferrous metals in the MF is also relatively small. The utilizability of lead (uPb) in MF is 9.14%, while uZn is 7.36%. uCu is relatively high (20.42%) due to the high Cu concentration in this fraction, but the utilizability of Fe is low (16.79%). Nonferrous metals exhibited high utilizability in the NMF. uPb is 90.86%, even though the Pb concentration (1.78%) in proportion to the input (1.67%) is only 6.7% higher, indicating a very low concentration. Concentrations of Zn and Cu in the NMF are 7.61% and 0.42%, respectively. The NMF had a lower concentration of Cu than the input. The Fe content in the NMF is significant at 30.01%, indicating a minor decrease from the 30.72% of Fe in the input raw material. The utilizability of Zn in the NMF is 92.64%. However, the Zn content (7.61%) in the NMF in relation to input has increased by 8.7%, which is quite low.

In comparison to the input (30.72%) and NMF (30.01%), the quantification of Fe (34.83%) in the MF indicates a low concentration. Iron is comprised in the glassy phase, spinels, franklinite, and wüstite. In a low magnetic field, one part of these mineral forms is transferred into the MF and the other part remains in the NMF, depending on their magnetic properties. However, the iron content in the MF is only 13.4% higher than that of the input. The MF’s insufficient uFe (16.79%) indicates 83.21% loss of Fe in the NMF. Thereby, there was no discernible separation of nonferrous metals from iron carrier components at a low magnetic field of 0.07T. Non-ferrous metals were partially isolated from the MF (1.03% Pb, 3.48% Zn, and 0.62% Cu), and therefore lost from further refinement procedure. Furthermore, their presence deteriorates the quality of the fraction in which Fe should be concentrated. A very small concentration of Fe in MF (34.83%) emerged under a low magnetic field. Given the same magnetic field settings, the concentration of Cu (20.42%) in the MF was high, which is not ideal from the standpoint of the product’s quality.

Pb-Zn slag separation under low magnetic field conditions was not successful, according to the data presented. More specifically, the Cu content in this fraction was lower than that of the input raw material, and no substantial concentration of nonferrous metals in NMF was achieved relative to the input. There was no noticeable increase in iron concentration in MF in comparison to the input.

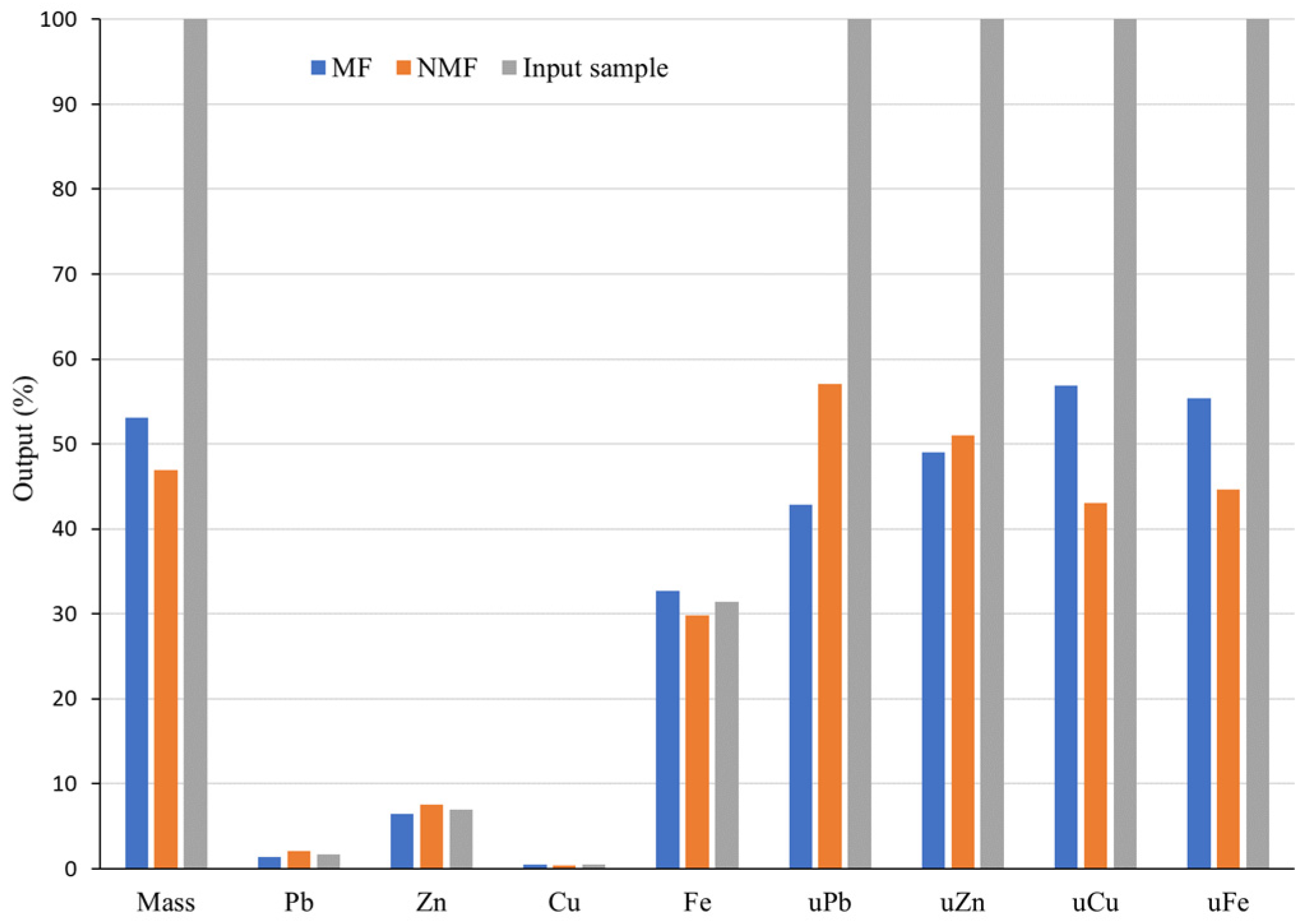

3.2.2. Magnetic Separation of Pb-Zn Slag by Disk Separator

The second MS experiment was performed using a magnetic separator with a disk. Separation was conducted in a dry state, with a magnetic induction more than 15 times higher than that of a Davis separator. The MF and NMF of the Pb-Zn slag sample were obtained following the disk separation test and both fractions were chemically analyzed by the AAS. The results are presented in

Figure 8 as a material balance.

The results displayed in

Figure 8 show that the separation of the MF and NMF was more successful than in the previous experiment, but still not perfect, even with a disk separator with strong magnetic induction (1.1T). The mass of MF acquired in this experiment was 53.11%, which is significantly higher than the mass obtained by Davis separator (14.81%). The MF comprised comparatively larger concentrations of nonferrous metals: 1.38% Pb, 6.44% Zn, and 0.49% Cu. This separation resulted in higher Pb and Zn concentrations in the MF compared to the experiment with a Davis separator (

Figure 7). Cu concentration in the input (0.46%) was lower than that of MF (0.49%). The copper concentration in the MF is undesirable in terms of the product’s quality. In contrast to the content obtained by the Davis separator, which operated in a low magnetic field (0.07T), the amount of nonferrous metals in the MF increased under a strong magnetic field (1.1T). For instance, the Zn content in the MF was 6.44%, which is slightly lower than the Zn concentration in the input sample (6.98%) and far higher than the Zn content obtained by the Davis separator (3.48%). The appearance of Zn in the MF can also be partially attributed to the presence of franklinite (ZnFeO

4) or amorphous forms that are chemically similar to franklinite.

The mass share of MF after the experiment in the disk separator is nearly 3.6 times higher than the mass obtained via Davis separator. This suggests a notable loss or use of non-ferrous metals. The utilizability of Pb (uPb) is 42.9%, while uZn, and uCu are 48.97% and 56.92%, respectively. Utilizabilities of the non-ferrous metals in the NMF are as follows: uPb is 57.1%, uZn is 51.03%, and uCu is 43.08%. Despite a 1.218 and 1.088-fold increase in Pb and Zn concentrations relative to input(s), respectively, these levels remain low. The concentration of Zn in the NMF of the sample treated with the Davis separator is approximately the same as the Zn concentration obtained by the disk separator, but the utilizability of Zn in the NMF of the Davis separator is significantly higher than that of the disk separator. Similar to uZn, utilizability of copper in NMF of Davis separator was higher than that of disk separator, eventhough Cu concetrations in both NMFs were the same.

Compared to the input, the concentrations of Pb (2.08%) and (7.6%) Zn in the NMF were higher. The amount of Cu (0.42%) in this fraction decreased in comparison to the input (0.46%). Furthermore, Fe content in the NMF is significant at 29.86%, exhibiting a small decrease from the Fe value (31.38%) obtained for the input raw material. The low concentration of iron in the MF (32.72%) in comparison with input and NMF can be explained by the fact that in a strong magnetic field, fewer magnetic minerals with lower iron content, such as spinels and franklinite composed of various divalent and trivalent cations (in this case, Fe and Zn), passed into the magnetic fraction.

When franklinite with a high Zn content is submitted to separation using a strong magnetic field, the Zn content in the MF increased. Weaker magnetic minerals with low Fe concentration were also separated, influencing an increase in Fe content in the magnetic fraction. In this case, Fe is concentrated in the MF with a small increase (4.3%) over the input. The utilizability of Fe (uFe) in the MF is 55.38%, resulting in a Fe loss of 44.62% in the NMF. Thus, using a stronger magnetic field (1.1T) in the Pb-Zn slag separation process did not result in significant separation of nonferrous metals from iron carrier components.

3.2.3. Mineralogical Analysis of Magnetic Separation Products – Optical Microscopy

According to the results of chemical analyses, the magnetic separation procedures applied to the Pb-Zn slag in two previously explained testing sets with different experimental conditions and magnetic induction strengths did not yield a suitable technological outcome. A mineralogical analysis of the resulting magnetic separation products was carried out in order to gain a better understanding of why the magnetic separation of Pb-Zn slag, which was intended to separate nonferrous metals from components containing iron, underperformed.

The structural elements of the analyzed samples are grouped into five formations according to the degree of freedom and the way they interconnect: (1) free grains - representing free mineral grains with about 100% visible surface; (2) inclusions - represent the examined mineral, which contains other minerals whose total surface area does not exceed 10–30%; (3) impregnations - represent the examined mineral, which is incorporated in other minerals where its total surface does not exceed 10–30%; (4) simple fusion - represents the examined mineral, which has fused with one mineral, where its total surface ranges from 30–70%); and (5) complex conglomerate - represents the examined mineral, which has conglomerated with several minerals, where its total surface ranges from 10–50%.

Microphotographs of the MF separated from the Pb-Zn slag sample obtained on a Carl Zeiss-Jena’s JENAPOL-U polarizing microscope are shown in

Figure 9a–f. The estimated percentage of free alloy grains in MF is 91%, while the percentage of alloy grains that are in the form of inclusions, impregnations, or simple fusions sums up to 9%. The size of the free grains ranges from 26 µm to 159 µm, while the inclusions, impregnations, or simple fusion diameters are from 50 µm to 74 µm. The inclusions whose dimensions range from a maximum of 20 µm to submicron dimensions are not included in the calculation because their mass share is small and it was not possible to separate them.

Figure 9a gives a preview of a simple fusion of one or more minerals grouped in a single formation. Free grains of alloys are visible in

Figure 7b–e.

Figure 7f depicts another simple fusion of minerals. All microphotographs were recorded in air and reflected light.

Microphotographs of the NMF of the Pb-Zn slag sample are given in

Figure 10a–f. The percentage of free alloy grains in this sample is 83%, while the percentage of alloy grains that are in the form of inclusions, impregnations, or simple fusions is 17%. The diameters of the free grains range from 35 µm to 140 µm. The inclusions, impregnations, or simple aggregates exhibited diameters in the range of 32 µm to 92 µm. Inclusions with dimensions from 20 µm to submicron dimensions are not included in the calculation. It was observed that the alloy content in NMF is higher compared to MF.

Figure 10a,b give a preview of two free alloy grains. Free alloy grain (blue) and simple fusion of alloys (red) are depicted in

Figure 10c. Two free alloy grains are also visible in

Figure 10d.

Figure 10e shows free alloy grain (blue) and simple fusion of alloys (red), while two free alloy grains are visible in

Figure 10f. All microphotographs were recorded in air and reflected light.

The study of the MF and NMF microphotographs of the Pb-Zn slag sample served to confirm whether this artificial raw material was adequately prepared for the magnetic separation process. In theory, the liberation of magnetic particles should be optimal. Specifically, the MF contained 91% free alloy grains, while only 9% of them coalesced with other grains through inclusions, impregnations, simple fusions, or complex conglomerates. Given that 91% of the non-ferrous metal alloy grains (copper, zinc, and lead) found in the MF are free, they ought to have passed into the MF during the MS procedure. The degree of freedom of the alloy grains in this sample is ideal, based on the visual assessment of the NMF microphotographs. Analysis of the test data showed that 83% of the alloy grains in the NMF are free, whereas 17% are fused in different ways with other grains. This indicates that free alloy grains of non-ferrous metals (lead, zinc, or copper) account for 83% of all the alloy grains found in NMF and that these grains entered the NMF during the magnetic separation process. Thereby, mineralogical analysis revealed that the Pb-Zn slag was adequately prepared for magnetic separation process. Grains derived from various slag components were optimally released because the input material was crushed to the theoretically ideal grain size class of -0.1+0.00mm.

3.2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis of Pb-Zn Slag Samples

As it was previously concluded, magnetic separation of the Pb-Zn slag sample using two distinct magnetic separators with different magnetic inductions produced unsatisfactory results. The chemical analysis of the outputs revealed that there was no adequate separation of non-ferrous metals into the NMF and iron-containing components into the MF. To better understand this problem and the outcomes, scanning electron microscopy, accompanied by an EDS system for targeted chemical analysis, was performed on the initial slag sample to identify the presence of certain elements in individual slag grains. SEM microphotographs of characteristic Pb-Zn slag grains are given in

Figure 11a–f.

Table 1 shows the semiquantitative chemical analysis (EDS) of Pb-Zn slag grains.

The first analyzed grain of the oxidized lead alloy (

Figure 11a), indicated as 11a/1 in

Table 1, has 75.23% Pb, 0.79% Cu, and 0.70% Fe. Although this percentage of iron is very low, it provides a certain degree of magnetism. The second oxidized lead alloy grain (11a/2), besides 55.73% Pb and 16.77% Cu, has 3.76% Fe. As in the prior situation, this grain has a low iron content, indicating low magnetism. The grain of the glassy matrix grain (11b/1,

Figure 11b) contained 7.03% Ca, 8.26% Si, and 29.05% Fe, as well as a large amount of copper (0.60%) and zinc (16.67%). Due to its high Fe concentration, this grain can be considered magnetic. Therefore, Cu and Zn constituents are transported with this grain and concentrated into the magnetic fraction, as seen in both magnetic separation studies. Two oxidized lead alloy grains, designated as 11c/1 and 11c/4, are observed in

Figure 11c. The initial grain (11c/1), in addition to the nonferrous metals (82.69% Pb and 2.36% Cu), is iron-free and thus nonmagnetic. The other grain (11c/4) has 0.95% Fe in addition to the nonferrous metals (79.05% Pb and 3.50% Cu). The iron content is minimal, although the grain can be described as low-magnetic. A similar situation occurs with the oxidized lead alloy grains marked as 11d/1 and 11d/2 (

Figure 11d). The first one contains nonferrous metals (84.62% Pb and 2.36% Cu), but does not contain iron in its composition. As such, it is undoubtedly non-magnetic. The other grain, in addition to lead, has 76.23% Pb and 0.54% Fe, making it low-magnetic. In addition to the nonferrous metals (36.97% Cu and 33.10% Zn), the oxidized copper-zinc alloy grain designated as 11e/1 contains 8.94% Fe (

Figure 11e). This grain is surely magnetic. The last investigated grain (11f/1,

Figure 11f) is certainly non-magnetic because it is composed of non-ferrous metals (90.70% Pb and 0.46% Cu) and contains no iron. This grain contains a certain amount of silver (0.97% Ag).

The EDS analysis of the scanned alloy grains and the glassy matrix indicate that non-ferrous metal grains have entered the magnetic phase. To be more specific, the grains of nonferrous metal alloys containing iron are showing a certain degree of magnetism, and as such, they pass into the magnetic fraction during magnetic separation. These results demonstrated why the magnetic concentration of Pb-Zn slag did not show the expected results. The majority of Fe was bound in mineral or amorphous formations; therefore, it was impossible to liberate via a mecanical procedure for concentration. As a result, the usable components could not be separated from the tailings to form an individual product.

3.3. Gravity Concentration of Pb-Zn Slag

The investigations were then directed toward separating and valorizing useful elements from Pb-Zn slag using the gravity concentration method. Several factors were explored before determining the most suitable GC settings. The key premise is that slag is not an ore, which implies that it contains more than just minerals. The methodology of the experiment was determined by the sample’s mineralogical properties (the presence of amorphous and crystalline phases), structural and textural characteristics, degree of cohesion (freedom) of components, and the fact that the sample contains useful components primarily as alloys. Namley Pb-Zn slag consists of alloy-mineral intergrowths and an amorphous phase [

1]. The investigated slag is composed of: (1) oxidized lead alloy with copper and iron (Pb, Cu, O, Fe): γ = 9.84-9.25 g/cm

3; (2) oxidized lead alloy with copper (Pb, Cu, O): γ = 8.73-9.21 g/cm

3; (3) oxidized zinc alloy with copper (Cu, Fe, Zn, O): γ = 6.33-6.73 g/cm

3; (4) wüstite grains: γ = 5.7 g/cm

3; (5) elemental iron grains: γ = 7.87 g/cm

3; (6) galena grains (PbS): γ = 7.2-7.6 g/cm

3; (7) sphalerite grains (ZnS): γ = 3.9-4.1 g/cm

3; (8) grains of amorphous phase (spinels) chemically similar to franklinite: γ = 5.07-5.22 g/cm

3; and (9) silicate grains (gelenite/akermanite/wollastonite): γ = 3.00 g/cm

3. The initial Pb-Zn slag sample had the same characteristics as the input sample for magnetic separation, with a particle size of -0.1+0.00 mm.

These tests marked the first attempts to conduct gravity concentration and subsequent valorization of Pb-Zn slag “Veles”. Because there are no predetermined standards, requirements, or attributes that must be met by the product made by concentrating Pb-Zn slag in order for it to be commercially viable, the success of gravity concentration cannot be evaluated solely on the basis of the tests conducted.

3.3.1. Concentration Criterion for Gravity Concentration Experimet

If the concentration criterion is greater than 1.5 (ζ > 1.5), the probability of successful gravity concentration of a raw material in a wet environment (water), i.e., mineral/component separation into different products, is high. The GC procedure was limited to obtaining two products, ∆T and ∆L, because the Pb-Zn slag had a metal alloy concentration of roughly 5-6% (i.e., tailings content is slightly more than 90%). As an output, the total raw material was separated into two parts: ∆L (the tailings fraction) and ∆T (the concentration of non-ferrous metal alloys).

The following formula is used to calculate the separation of a two-component system, including grains of oxidized lead-copper alloy and an amorphous phase (spinel), when the concentration conditions for their GC in a thin layer of water are satisfied:

Separation in a two-component system consisting of oxidized zinc-copper alloy grains and an amorphous phase is conducted using the formula:

The experiment used a concentration criterion of 1.5 due to the higher first concentration criterion (ζ1 = 1.93) and lower second concentration criterion (ζ2 = 1.4) compared to the theoretical value required for successful separation of two minerals or components.

The separation of the copper-containing amorphous phase (spinel) grains from the oxidized zinc alloy grains can be challenging. The worst-case scenario is adopting the amorphous phase’s specific mass as γ = 5.07–5.22 g/cm3, which is also the specific mass of franklinite and magnetite. The amorphous phase might be similar to franklinite, but in reality, this component of slag is far more complex, containing Si, Ca, Mg, and Al. The amorphous phase has a specific mass of less than γ < 5.0 g/cm3, however, a larger value (5.6 g/cm3) was chosen for safety.

3.3.2. Grain Size Distribution of the Pb-Zn Slag Used for Gravity Concentration

Five size classes obtained by the wet sieving were employed as the grain-size classes for the GC: -0.1+0.075 mm; -0.075+0.053 mm; -0.053+0.037 mm; -0.037+0.025 mm; -0.025+0.00 mm. The grain size distribution of the sample used for GC is presented in

Figure 12.

The initial crushed sample of Pb-Zn slag for GC has a mean grain diameter of d50 = 0.86 μm and a maximum diameter of d95 = 94.82 μm. Even after the sample was ground to a size of -0.1 mm, 18.88% of the finest class (-0.025 + 0.00 mm) was present. All of the alloy’s valuable components that are softer than the tailings in this paragenesis move to the finer classes and are crushed more readily; therefore, this is undesirable. The classes -0.1+0.075 mm, -0.075+0.053 mm, -0.053+0.037 mm, and -0.037+0.025 mm contributed 22.45%, 25.11%, 17.79%, and 15.77% of the overall mass share, respectively.

3.3.3. Load Balance of the Gravity Concentration of Pb-Zn Slag

Gravity concentration was conducted on a Wilfley 13 shaking table (described in

Section 2.6). When using the gravity concentration approach, it is difficult to visually distinguish the fractions of the slag by color (there is a visible separation on the table, i.e., bands are distinguishable, but the color difference is minimal), which is very different from ores. Sub-samples were taken from each grain-size class and treated on the shaking table. Following GC, all acquired compounds were dried, their masses determined, and samples prepared for chemical analysis. Based on the chemical analysis, a load balance was determined, demonstrating the concentrations and utilizability values of all the obtained products.

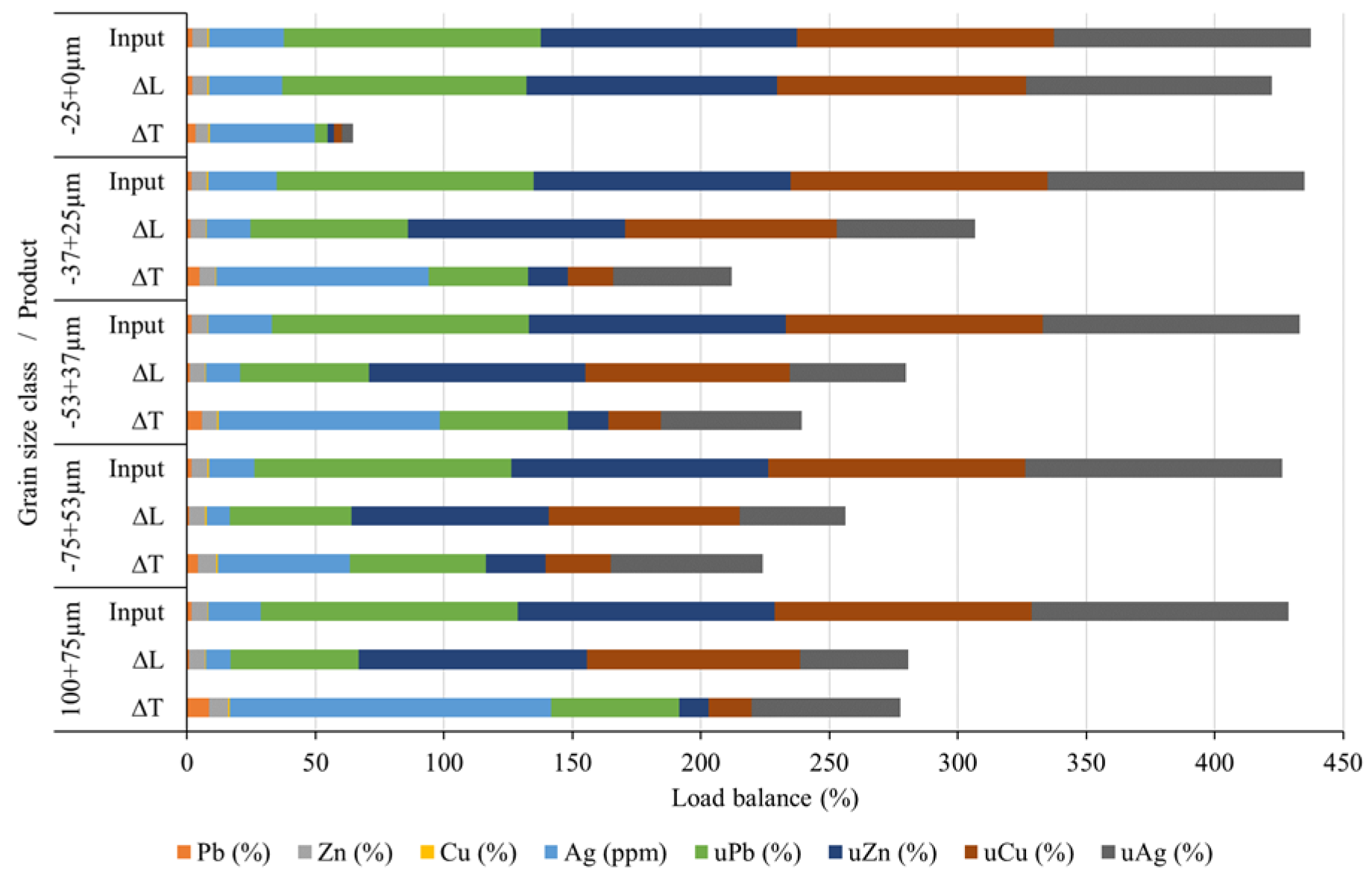

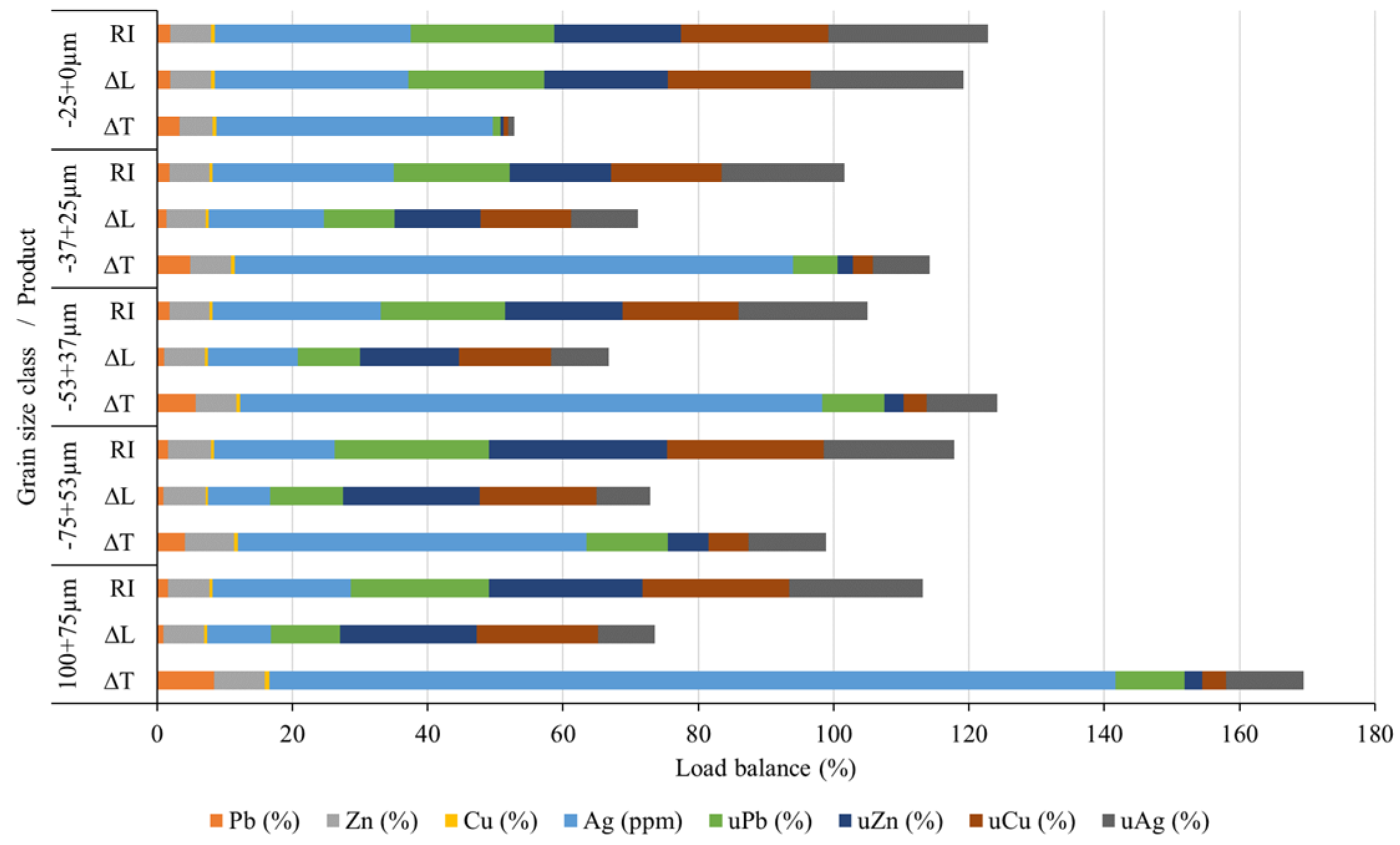

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 illustrate the load balance based on grain size classes and input, respectively.

Figure 13 displays the load balance for each class, which equals 100%.

Figure 14 shows the load balance, which takes into consideration all classes and products in proportion to their input. In addition,

Table 2 shows the cumulative products of GC given as metal (Pb, Zn, Cu, and Ag) concentrations and utilizabilities.

According to chemical analysis, the original Pb-Zn slag sample has a high content of zinc (≈ 7%), lead (≈ 2%), and copper (≈ 0.5%) [

37]. However, the alloy grains as usable components do not contain significant amounts of zinc or copper; instead, the tailings do. On the other hand, lead is primarily found in oxidized lead alloy grains with copper. Pulverizing the material to a fineness of - 100+0.00 μm increased participation in the finest class -25+0.00 μm to 18.88% (

Figure 12). The fact that non-ferrous metals are very soft and quickly broken-down means that they easily slip into the smallest classes during grinding, and thus they are being lost from the valorization procedure.

Based on the data illustrated in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, it can be concluded that the separation of individual components into different products based on size classes calculated using the concentration criterion is well performed. In the coarsest class (-100+75 µm), 9.46% of the total mass belongs to the concentrate fraction, while the rest (90.45%) is in the tailings fraction (

Figure 3). Alloy grains are easily separable in this class. Total ΔT fraction is 20.44%, 15.79%, and 14.97% for the three following grain size ckasses. Useful components summed up to only 3.03% in the finest class, which means that this class can easily be disregarded as mainly tailings. This demonstrates that the gravity concentration parameters used in this experiment were correctly determined and implemented.

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 show satisfactory results for separating lead and silver concentrates (ΔT fractions of Pb and Ag). The results obtained for the separation of zinc and copper concentrates (ΔT fractions of Zn and Cu) are somewhat inferior. As it can be seen from

Figure 13, the coarsest class (-100+75 μm) produced the highest concentrations of Pb, Zn, Cu, and Ag (ΔT fraction): 8.44%, 7.42%, 0.77%, and 125 ppm (g/t), respectively. Smaller size classes gave lower concentrates (ΔT) of non-ferrous metals and silver. For instance, the finest class (-25+0 µm) had the following concentrations of Pb, Zn, Cu, and Ag: 3.37%, 4.82%, 0.54%, and 40.88 ppm, respectively. Therefore, the majority of useful elements are located in the coarser classes, from where they can be separated.

The best results in separation using GC were achieved for lead and silver. Despite the relatively low content of lead in the input raw material (1.75%), Pb concentrates reached mass share from 3.37% (in the fine class -25+0.00 μm) to 8.44% (in the class -100+75 μm), as can be seen in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14. The silver quantity in the concentrate ranges from 125 g/t (for the class -100+75 μm) to a minimum of 51.5 g/t for the class -75+53 μm. Concentrations of Zn range from 5 to 8% in useful grain size classes, while Cu is below 1% in all classes.

The content of lead in the cumulative concentrate (i.e., all ΔT fractions combined) is 5.28% (

Table 2), with the utilizability of lead in it being 39.22%. The content of silver in the cumulative concentrate is 76.12 g/t, with the utilizability of silver being 42.68%. The results regarding the content and utilizability of lead and silver obtained during gravity concentration indicate that silver follows lead, that is, there is free silver and invisible silver in the structure of the lead alloy intergrowths [

37]. Free silver, which is very fine, sizing 2–5 μm, probably passed into the finest class (-25+0.00 μm) during comminution and ended up in tailings to a significant extent. Namely, the highest silver content is in the -25+0.00 μm class (RI = 28.97 g/t), and its ΔL is 28.60 g/t (

Figure 14). As it was mentioned, the gravity concentration procedure was more successful in the separation of Pb and Ag than Cu and Zn. For each grain size class, the Zn concentrates (ΔT) were higher than its tailings fraction (ΔL), except for the finest size class (-25+0.00 μm), in which ΔL was higher than ΔT. The copper content for each grain size class exhibited a higher ΔT fraction than ΔL fraction. This means that separation has been successfully achieved. The zinc content in the cumulative concentrate (all ΔT fractions combined) is 6.69%, with a utilizability of 14.16% (

Table 2). The copper content in the cumulative concentrate is 0.58%, with an utilizability of 16.58%. The GC underperformance with zinc and copper can be attributed to the small concentration criteria of 1.4 in the two-component system of oxidized zinc alloy grains with copper and an amorphous phase.