2. Background

Computers can be vulnerable to external threats and, as computers and similar devices are constantly connected to a network and are widely used by a large number of people to communicate with each other and share information, constant monitoring and detection is necessary, especially because not all people have a digital education. The Cybersecurity has three pillars, known as CIA: Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability, and any action compromising any of these pillars is considered to be a threat or danger. There is a variety of cyber-attacks that violate CIA but, more specifically, the process of tracking and evaluating network or computer traffic for indications of infiltration is known as intrusion detection. Businesses need to safeguard their networks using a range of technologies and detection techniques to counteract the many assault, intrusion, and compromise tactics that cybercriminals employ nowadays.

These considerations highlight the urgency to improve the current security systems, mostly represented by antivirus software, firewalls and intrusion detection systems (IDS). Firewalls monitor incoming and outgoing traffic based on rules and policies, acting as a barrier between secure and untrusted networks. Within the protected network, an IDS detects suspicious activity to and from hosts and within the traffic itself, taking proactive measures to log and block attacks. There are two categories of IDS: network-based intrusion detection systems (NIDS) and host-based intrusion detection systems (HIDS). HIDS monitors and analyzes activities on the system (host) where it is installed, monitoring parts of the dynamic behavior and state of the system, including incoming and outcoming traffic of the device, as well as changes to local files. NIDS monitors network traffic by offering sophisticated real-time intrusion detection capabilities and are strategically placed at various points on the network to monitor incoming and outgoing traffic to and from devices on the network. Based on the mode of detection, current NIDS can be classified as either misuse-based (also known as signature detection) or anomaly-based. One crucial area of study and advancement in the field of intrusion detection is anomaly-based network intrusion detection. Techniques for detecting anomalies simulate system characteristics in order to produce normal, or standard, behavior. When something happens that's not typical, the intrusion detection system (IDS) recognizes it as suspicious activity and sends out an alert that can be used to identify zero-day assaults. This model has two key drawbacks: (1) a high rate of false positives; and (2) how to develop a model for normal behavior and how to handle the evolution of normal user behavior. However, with signature-based detection, potential intrusions are found by comparing recorded events to recognized threats or attacks. Signatures are a common term used to describe known attacks. Ports, source addresses, and destination addresses are all included in signatures. These kinds of detection systems typically have excellent accuracy against known threats because the signatures are known. There is a significant disadvantage to this kind of approach, though. The system will not be able to identify an attack in the case of a zero-day assault or a modification of a known attack. SIDS is unable to do this because it only uses regular expressions and matching strings. As such, it is more accurate and produces fewer false alarms than the anomaly detection approach, but it is only useful for detecting known assaults; it is useless for detecting unknown attacks. For instance, it could be challenging for signature-based NIDS to identify a newly identified intrusion type or vulnerability if it isn't yet included in CVE. A shift in the standard data model could prompt an anomaly-based NIDS to take quick action.

As mentioned before, the three primary pillars of information security are CIA. However, information security also heavily relies on accountability and authenticity. Attacks against confidentiality, for example, deal with passive attacks like eavesdropping; attacks against integrity, on the other hand, deal with active attacks like system scanning attacks, like "Probe"; and attacks against availability, on the other hand, deal with attacks that cause disruptions to network resources, making them unavailable to regular users, like distributed denial of service (DDoS) and denial of service (DoS). An attack is now described as a sequence of events that may jeopardize a resource's availability, confidentiality, data integrity, or security policy of any kind. In order to stop malicious activity on computers and networks, an intrusion detection system (IDS) seeks to identify all of these kinds of attacks.

The next subsection will explain the stages of a cyber-attack.

2.1. Stages of Cyber-Attack

Cyber threats typically vary in complexity, with different attacks having different targets, effects, and scope. All the literature, however, agrees that an attack may be divided into five stages: reconnaissance, exploitation, reinforcement, consolidation, pillage. The system should notice an attack within the first three phases; but, once it reaches the fourth or fifth step, it will be fully compromised. In the reconnaissance stage, the malevolent user attempts to learn as much as they can about the target system, such as its operating systems and applications, user accounts, network architecture, and other pertinent details. In order to develop an efficient assault strategy, the objective is to collect as much data as possible. During the exploitation phase, a malicious user uses a specific service in an attempt to access the target machine. A service may be classified as abusive, subversive, or hacked. Passwords that have been stolen are considered abusive, and SQL injection is considered subversion. Following an unauthorized forced entry into a system, a malicious user installs more tools and services to exploit the newly obtained privileges during the reinforcement phase. A malicious user tries to obtain total access to the system using the misused user account. Ultimately, a malicious user makes advantage of the programs that the accessible user account may access. During the consolidation stage, a malicious user obtains total control over the system and the degree of privilege required to accomplish their objectives. The last phase is called looting, and it involves data theft, crucial system corruption, and interruption of corporate operations as potential malevolent user actions. There is a chance for errors in both hardware and software since computers and networks are built and developed by people. Vulnerabilities may result from these defects and human mistake.

3. Related Work

Recently, extensive research has been conducted on the application of supervised machine learning techniques to automate the process of intrusion detection in network connections. Experiments conducted in [

2] compared different machine learning algorithms for Intrusion Detection System (IDS) using the KDD-99 Cup dataset. The Supervised Learning methods used for the detection task are: Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest, AdaBoost Algorithm, Multi-Layer Perceptron, Naïve Bayes. The results show that the worst performance is provided by the Logistic Regression, with 79.7% accuracy, the best performance is provided by Random Forest with 99% accuracy, followed by the KNN, with 94.17% accuracy, and Naïve Bayes with 92.4% accuracy.

[

3] aimed at the problem of network intrusion classification using the NSL-KDD dataset. In the study, a model is proposed that applies the RF algorithm for intrusion detection, classifying various types of attacks: DoS, Probe, R2L, U2R. After the phase of data pre-processing and feature selection, the proposed approach was evaluated in terms of accuracy and FPR (false positive rate) and compared with the J48 Tree algorithm, reporting in the case of DOS attack an accuracy of 99.67%, which is 7% more than the J48 algorithm.

Using UNSW-NB15 datasets, the authors of [

4] examined the effectiveness of top supervised machine learning methods. The J48 decision tree, Naïve Bayes, Logistic Regression, and SVM models with three distinct kernels (SVM-RBF, SVM-Polynomial, and SVM-Linear) were all compared. With an accuracy of 89.26%, Logistic Regression had the highest performance, followed by the J48 algorithm's 88.67% accuracy.

In order to categorize each event as normal or attack, the research of [

5] aimed to use the Naïve Bayes supervised classification for the NSL-KDD dataset using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). In essence, the classification uses features to determine category labels; however, because the NSL-KDD dataset has a large number of attributes, PCA is utilized as a feature reduction approach. The highest accuracy recorded in the findings was 86.5%.

In order to stop intrusions as soon as possible, the perfect IDS should be able to swiftly identify zero-day attacks with high accuracy and few false positives. The aim of [

6] was to develop an intrusion detection model that combines machine learning algorithms with feature selection and reduction techniques. The goal was to identify intrusions quickly and accurately, while also minimizing false positives. The research tested ten widely used machine learning algorithms, BayesNet, Naïve Bayes, Logistic, Random Tree, Random Forest, Bagging, J48 DT, PART, OneR, and ZeroR, using the NSL-KDD dataset. The best performance among these was reported by Random Forest.

In [

7], four different algorithms are used on the UNSW-NB15 dataset for the classification of cyber-attacks. These supervised techniques include J48, ZeroR, Random Forest, and Naïve Bays. Correlation-based Feature Selection (CFS) was used to create an ideal subset of features. In this investigation as well, the Random Forest method yields the highest accuracy (97.6%), and recall, precision, and F-measure (0.976). With a recall, precision, and F-measure of 0.681 along with an accuracy of 68.06%, ZeroR seems to be the worst model.

In [

8] different machine learning techniques were studied using the NSL-KDD dataset, with the different model building steps. Supervised machine learning algorithms include k-Nearest-Neighbors (KNN), Decision Tree, Random Forest, Naïve Bayes, Neural network, AdaBoost. These algorithms were compared at each stage of the data pre-processing steps to analyze which combination of algorithms is the best to be suitable for an intrusion detection system. For Decision Tree, the CART algorithm with random state set to 0 is used. For KNN, 10 nearest-neighbors are used as a parameter. For Random Forest, 100 random states are used as parameter. For Naïve Bayes, its default parameters are used. For the neural network, Multilayer perceptron is used, with backpropagation algorithm to train the model. For Multilayer perceptron, 10 is used as the number of random states. A 100 number of estimators and 0 number of random states are used for AdaBoost. For data preprocessing, categorical feature data are mapped to binary data by applying one-hot coding. The authors applied some feature scaling and feature reduction techniques, as well as standardization and normalization individually to analyze the result of these techniques on the dataset. Then, each selected ML algorithm is applied to test the result against an unscaled model. Several feature reduction techniques were compared for this analysis, including low variance filter, high correlation filter, Random Forest, Incremental Principal Component Analysis (Incremental PCA). For the data set "NSL-KDD" there is an imbalance problem, the authors applied some over-sampling techniques: SMOTE, Borderline-SMOTE, ADASYN. Among these selected models, “KNN+Normalization+correlation filter” with Borderline SMOTE had the best performance in terms of accuracy (85.3%) but longer prediction time (62.54 s). On the other hand, the best model in terms of prediction time was "Decision Tree+standardization+correlation filter", with a prediction time of 0.01 s, the shortest time observed, but it achieved a lower accuracy. Therefore, considering accuracy for the best overall performance, KNN will be the best choice for an IDS.

Three traditional tree-based machine learning algorithms are trained and tested in [

9], using the NSL-KDD benchmarking dataset: Random Forest, Decision Tree, and XGBoost. In order to improve and optimize the algorithm's performance for accurate prediction, as well as to enable a smooth training process with the least amount of time and resources, normalization and feature selection approaches are employed in conjunction with data pre-processing. XGB reported an accuracy of 95.5% in the detection rate.

In [

10], XGBoost is used with two datasets designed to evaluate NIDS machine learning algorithms: NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15. The results showed that it is possible to achieve good performance (accuracy of 0.8864 and 0.9334 respectively) using a limited fraction of the complete parameter space. The most relevant model parameters for achieving such performance are: ntrees, max_depth, eta, sample_rate, gamma, reg_lambda, reg_alpha.

In [

11], the authors compared various machine learning techniques for classifying network data into threats/non-threats using the UNSW-NB15 dataset. The models tested were ANN, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and the proposed AdaBoost technique based on a Decision Tree classifier. The ANN, achieved an accuracy of 89.54%; the SVM, with the RBF kernel, an accuracy of 94.7% was obtained. The authors proposed a Decision Tree-based classification approach using AdaBoost. The parameters used in the AdaBoost model are maximum depth = 2 and algorithm = 'SAMME.R', achieving an accuracy of 99.3%.

In the context of the IoT-23 dataset, [

12] implemented Random Forest, Naïve Bayes, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Decision Tree algorithms to detect anomalies in network data. The Random Forest algorithm achieved the best results, with an accuracy of 99.5%, while the worst results are achieved by the Naïve Bayes, with 78.84% accuracy.

A machine learning-based intrusion detection system (IDS) with two hidden layers (a first layer with 32 neurons and a second layer with 16 neurons) was published by the authors of [

13]. The number of features determines the input layer. For every scenario in the IoT-23 dataset, the output layer is associated to the labeled classes. The feature selection method used by ANN is called Sequential Forward Feature Selection (SFS).

In [

14], three classifiers were used to classify network traffic data: Deep Feed-Forward Neural Network, Random Forest, and Gradient Boosting Tree. Two publicly available datasets, UNSW-NB15 and CICIDS2017, were used to evaluate the proposed method. The results show high accuracy with Deep Feed-Forward Neural Network for both binary and multi-class classification on the UNSW-NB15 dataset, achieving 99.16% accuracy for binary classification and 97.01% for multi-class classification. On the other hand, Gradient Boosting Tree achieved the highest accuracy for binary classification with the CICIDS2017 dataset at 99.99%, while for multi-class classification, Deep Feed-Forward Neural Network had the highest accuracy at 99.56%.

In [

15], a Deep Neural Network composed of three parts was proposed: input layers, hidden layers, and output layers. The structure includes an input layer with 41 neurons, 4 hidden layers each with 100 neurons, 1 fully connected (FC) layer with 5 neurons, a softmax layer, and an output layer with 5 neurons. Experiments on the KDD99 dataset demonstrated a maximum accuracy of 99.9%.

Using publicly available network-based intrusion datasets like KDD-99, NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15, and CICIDS 2017, the authors of [

16] focused their research on assessing the effectiveness of several classical machine learning classifiers (Logistic Regression, Naïve Bayes, k-Nearest Neighbor, Decision Tree, Random Forest, SVM) applied to NIDS. They also proposed a deep neural network architecture with an input layer, five hidden layers, and an output layer. To assess how well alternative models and the suggested model performed on various NIDS datasets, two distinct test scenarios were taken into consideration: 1) The network connection record is classified as either benign or attack; 2) The attack is classified into its respective categories and the network connection record is classified as either benign or attack. When it comes to accuracy, the suggested model performs better than traditional machine learning algorithms—often much better in multi-class classification on several datasets, with competitive outcomes even in the binary case.

The authors in [

17] presented their approach to IDS classification using the RNN model through six activation functions (SoftPlus, ReLU, Tanh, Sigmoid, LeakyReLU, ELU (Exponential Linear Unit)). They calculated accuracy, recall, and precision for the KDDCup 99 dataset, and results showed that the LeakyReLU function provides the best performance, achieving 97.77%, 87.85% and 99.38% in accuracy, precision and recall.

The study presented in [

18] presents an intrusion detection model with a CNN-based classifier trained on KDD-99 dataset. The proposed approach revised the LaNet-5 model [

19] incorporating the gradient descent optimization algorithm (i.e., the adaptive delta algorithm) to fine-tune the model parameters. The prediction accuracy of threat detection is 99.65%, higher than the existing LeNet-5 classifier (about 95%).

In recent years, many studies have used CNN or RNN to perform intrusion detection tasks based on spatial and temporal features. [

20] evaluated the performance of two deep learning RNN models (LSTM and GRU) with 2 (LSTM2 and GRU2), 3 (LSTM3 and GRU3) and 4 (LSTM4 and GRU4) hidden layers. The best performance on the NSL-KDD dataset was obtained using RNN LSTM4 and GRU3 with a maximum accuracy of 82.78% and 82.87% respectively.

The authors of [

21] proposed two deep learning models trained on NSL-KDD dataset, which are LSTM and the combination of convolutional neural network and LSTM (CNN-LSTM) for intrusion detection system. Normalization, scaling and conversion to numeric form were performed on the data, as LSTM only accepts numeric inputs. In the experimental phase, LSTM-only and CNN-LSTM achieved approximately 88% and 92% in terms of accuracy.

MINDFUL, a network intrusion detection approach, was introduced by [

22]. Using a convolution neural network that has been trained on a multichannel representation of network flows, this acquires an intrusion detection model. Using feature vectors created with these autoencoders, two autoencoders—one from the normal flow and the other from the attack flow—provide the feature vector representation of the network flows. The work's goal is to add class-specific information to the original flows' representation to enhance it. The depiction that is produced offers a fresh interpretation of the original flow. Each sample is thus represented as an extended multichannel sample in three dimensions, including the two vectors recovered by the autoencoders in addition to the original raw vector. Thus, MINDFUL combines an unsupervised approach for multichannel feature construction, based on two NN autoencoders, with a supervised approach that exploits cross-channel feature correlations. The authors assess the efficacy of the intrusion detection algorithm employed in MINDFUL by examining three benchmark datasets: KDD-99, UNSW-NB15 and CIC-IDS2017. The architecture takes X training samples as input. The two autoencoders are used for each training sample

in order to return the reconstructed features

and

. These new features are used to create a new augmented dataset that is used as input for a 1-CNN neural network. Experimental results reported binary accuracy of 92.49%, 93.40% and 97.90% on KDDCUP99, UNSW-NB15 and CIC-IDS2017 respectively.

Using recurrent patterns based on deep learning, [

23] presented an end-to-end model for the detection and classification of network attacks. Three recurrent pattern types (RNN, LSTM, and GRU) were taken exploited since the network traffic flow had temporal and sequence properties. SDN-IoT, KDD-99, UNSW-NB15, WSN-DS, and CICIDS-2017 datasets were used for the tests. In addition to performing dimensionality reduction, the authors per-formed dimensionality reduction and also employed a simple feature fusion approach that combined features from the RNN, LSTM, and GRU hidden layers. After that, an ensemble me-ta-classifier, also known as a stacking classifier, which combines several classification models, receives the fused features of the recurrent hidden layers. The meta-classifier is a two-step process that employs RF and SVM for prediction in the first stage, stacks the predictions in the second stage, then uses logistic regression in the third stage to identify and classify network threats. The findings demonstrate that the suggested approach swings between 89% and 99% in the attack categorization test and achieves 98–99% accuracy in the attack detection task across all datasets.

[

24] presented an attack detection framework using a deep learning model modeled on the IoT-23 dataset. The proposed mechanism uses a CNN-LSTM. When it comes to the experiments, the authors first tested the CNN alone, which does not perform well in classifying attacks such as CC, File Download, HeartBeat, and PartofHorizontalPortScan. However, it performs substantially well in identifying benign features with 94% accuracy. For the hybrid model, the problem was converted to a binary classification problem, by aggregating all the classes identifying the several attacks; this model, on the other hand, performs quite well in identifying malicious devices with 96% accuracy.

A novel method for network intrusion detection utilizing multistage deep learning image recognition is presented in the paper in [

25]. Four-channel (red, green, blue, and alpha) pictures are created using network features. The ResNet-50 deep learning model is then trained and tested using classification on the photos. UNSW-NB15 and BOUN Ddos, two publicly accessible reference datasets, are used to assess the suggested methodology. The proposed technique in the binary classification phase achieves a 93.4% accuracy rate in identifying regular traffic in the UNSW-NB15 network intrusion dataset. It achieves 99.8% accuracy in identifying generic attacks, 86% accuracy in identifying reconnaissance attacks, and 67.9% accuracy in identifying exploits attacks during the attack type identification phase.

CNN was used by the authors of [

26]. It was used to design and implement an anomaly detection model for Internet of Things networks that can identify and categorize binary and multiclass abnormalities. A multi-class classification model is constructed using the CNN 1D, 2D, and 3D models. Transfer learning methodology was used to carry out the binary classification process. The CNN1D, CNN2D, and CNN3D multi-class classification models pre-trained on the IoT-DS-2 dataset were initially utilized by the authors to apply the idea of transfer learning to the binary classification of the IoT-DS-2 dataset. Four existing datasets (BoTIoT, IoT Network Intrusion, MQTT-IoT-IDS2020, and IoT-23) combine to form IoT-DS-2. In the subsequent phase, they classified datasets from BoT-IoT, IoT Network Intrusion, MQTT-IoT-IDS2020, IoT-23, and IoTDS-1 into many classes using the same pre-trained learning model.

The multi-class and binary CNN models are validated using accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score. The CNN structure is good at extracting spatial aspects of data flow, but it performs a terrible job at extracting long-distance dependent information. In comparison, even though the GRU structure has a large number of parameters and requires a lengthy training period, it is more successful at extracting information that is reliant on distance and can prevent forgetting throughout the learning process. CNN-GRU is proposed by [

27], that combines GRU with convolutional neural network. Using a CNN, spatial features are collected and then combined using average-pooling and max-pooling, with the attention mechanism (CBAM) used to give each feature a distinct weight. At the same time, to achieve comprehensive and effective feature learning, the features of long-distance dependent information are simultaneously extracted using a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU). Based on the UNSW_NB15, NSL-KDD, and CIC-IDS2017 datasets, the suggested intrusion detection model is assessed. The experimental findings indicate that the classification accuracy achieves 86.25%, 99.69%, and 99.65%, respectively.

In [

28], five deep learning algorithms were suggested to be applied in the study in order to distinguish between malware and benign traffic in network traffic. Among the classifiers utilized there are LSTM, Random Forest, Catboost, XGBoost, and Convolutional Neural Network models. This study's primary goal is to use the IoT-23 dataset to investigate the network behavior and traffic traces of Internet of Things devices. After preprocessing the dataset to eliminate redundant or missing data, a feature engineering approach was used to extract the most important features. With a rating of 89%, RF has the best detection accuracy to distinguish between malware and safe purchases. The accuracy of the XGBoost and CatBoost classifiers was 89%, which is the same. With 10 layers, the suggested CNN model attained an accuracy of 84%. The worst accuracy was achieved by LSTM, with a value of 78%.

[

29] designed and developed LSTM, BiLSTM and GRU models for anomaly detection in IoT networks. Seven datasets were used to conduct multi-class and binary classification experiments using the proposed anomaly detection models, including NSL-KDD and IoT-23.

4. Materials and Methods

The primary technology of NIDS is still traditional machine learning techniques, which are more interpretable, easier to use, and unrestricted by processing capacity than deep learning techniques. A growing number of intrusion detection techniques are based on deep learning, which is developing quickly.

4.1. Decision Tree (DT)

A decision tree is a machine learning approach that uses a top-down tree form to illustrate every conceivable decision outcome. Three components are used to build the tree: decision nodes, branches, and leaf nodes. The if-then condition for categorizing an item is represented by the decision node, a branch denotes a potential attribute value and the leaf node represents the class or label. DT is advantageous in both classification and regression settings, more specifically, in scenarios where instances are attribute-value pairs with every possible value for each attribute being disjoint; target features are discrete attributes; there is an error in the training data, or the training data contains missing attribute values. Because Decision Tree just employs entropy and information gain for feature selection, it outperforms all other stand-alone classifiers. Finding the feature that most effectively separates the instances into the appropriate classes is the key challenge. Furthermore, while the model has an advantage over outliers and missing values, it has a propensity to overfit on the data. Any change in the dataset can also result in significant changes in the model. However, by restricting the tree's depth, this overfitting can be avoided or reduced. The C5.0 classifier has excellent accuracy, detection, and false alarm rates for IDSs. More precisely, C5.0 is quicker and uses less resources, making it suitable for developing an intrusion detection system with a big database.

4.2. Naïve Bayes (NB)

Based on the Bayes theorem, Naïve Bayes is a probabilistic classifier. With categorical values and small datasets, this probabilistic machine learning approach performs well, in comparison to other classifiers. Gaussian Naïve Bayes, Bernoulli Naïve Bayes, and Multinomial Naïve Bayes are the three Naïve Bayes algorithms. For continuous data values, Gaussian Naïve Bayes is employed; for binary values, Bernoulli Naïve Bayes; for discrete values, Multinominal Naïve Bayes. Naïve Bayes is easier and quicker for IDS. The foundation of all Bayesian naïve classifiers is the idea that each feature's value is independent from all other features' values, as shown in (1), where

is the conditional probability that the data belong to each class,

is the number of classes,

is the k-th class,

is the number of features,

is the a priori probability of

, and

is the conditional probability of the feature

given the class

.

To compute a class a priori, one must assume a feature distribution (i.e., a model of events) constructed from the training set. It's possible that distinct attack types cannot be detected using the presumption that characteristics are independent of one another.

4.3. Logistic Regression (LR)

When the value of target variable is categorical in nature, the classification procedure known as logistic regression is employed. When the data in question have a binary output, meaning they belong to one class or another or are either 0 or 1, logistic regression is most frequently utilized. The sigmoid function is used by logistic regression to determine a label's likelihood. A mathematical tool for mapping any predicted probability value to a different value between 0 and 1 is the sigmoid function. Any real number between 0 and 1 can be mapped to another value with this function. The sigmoid function's equation is displayed in (2). If

is a large positive number, this yields a

value that is near to 1, and if

is a huge negative value, it yields a value that is extremely close to 0. The input can be sent through a standard linear function once the value has been compressed toward 0 or 1, however at this point, the inputs can be divided into other categories.

Apart from how they are applied, logistic regression and linear regression are quite similar. Classification issues are solved with logistic regression, whereas regression problems are solved with linear regression. In logistic regression, a "S"-shaped logistic function with two maximum values (0 or 1) is fitted in place of a regression line.

The output of a linear function, , is first computed; this result serves as the sigmoid function's input. After that, we compute and get the prediction , which depends on . Therefore, will be near to 1 if is a high positive number. On the other hand, will be near zero if has a significant negative number. As a result, will always fall between 0 and 1. The prediction may be easily classified by applying a threshold value of 0.5. Therefore, it is presumed that y equals 1 if the prediction is bigger than 0.5. If not, we'll presume that . While binary classification cases are the ideal fit for logistic regression, it may also be used for multi-class classification tasks, or classification tasks that involve three or more classes, if a "one versus all" technique is used, which treats the classes as separate binary classification issues. Therefore, logistic regression primarily refers to binary logistic regression with binary target variables, while it may also be able to predict other target variable types. Logistic regression may be categorized into the following types based on the number of categories: Binomial or Binary, Multinomial. A dependent variable in binary classification will only have two potential types: 1 and 0. These variables might stand for things like win or lose, yes or no, success or failure, etc. In the multinomial scenario, the dependent variable may contain three or more potential unordered categories, or the types may not have any quantitative significance.

4.4. XGBoost

Regularized gradient boosting, or XGBoost [

30], is a refined form of gradient boosted machine (GBM). GBM belongs to the group of algorithms that work together to enhance Decision Tree performance. It combines weak classifiers, such Decision Trees, in a sequential manner, similar to other boosting techniques, enabling them to maximize any differential loss function and create a powerful prediction model. The prediction errors of each current learner (tree) are improved by utilizing the predictions of prior learners.

By adding all the scores of leaves that are detected evaluating a certain test sample, the ensemble tree generates its final prediction. The total of the predictions produced by the trees that minimize the prediction error is the final prediction, or h(x), for a given sample S. The hyper-tuned parameters for GBM are: 500 estimators, maximum tree construction depth is 3, minimum samples required for splitting 100 and learning rate 0.1. XGB uses the same gradient boosting theory as GBM. The modeling details are the only significant distinction between them. While GBM solely considers variance, XGB utilizes a more regularized model formalization to reduce overfitting and boost generalization ability. The regularization parameter (

) is expressed mathematically in (3), where

is the number of leaves in the tree,

is the score on the j-th leaf,

represents the regularization term that controls the complexity of the model.

Gradient boosting is a technique used by XGB to improve the loss function during model training. Generally, the LogLoss (L) function is represented as in (4), where

is the total number of observations,

is the predicted probability that an observation

is in class

, and

is the binary indicator of whether the predicted class

is the correct classification for a given observation

. Most importantly,

regulates the model's simplicity while

affects its predictive power. The usage of sparse matrices (DMatrix) with sparsity-aware algorithms, enhanced data structures, and support for parallelization are the primary implementation improvements of XGB. Hence, XGB makes use of hardware to process data quickly while using less memory (primary memory and cache). The optimal parameter values obtained for XGB are: 100 estimators, maximum tree depth is 8, minimum child weight value is 1, minimum loss reduction and sub-sample ratio are 2 and 0.6, respectively.

4.5. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

Support Vector Machine (SVM) [

31] is a classification technique that employs just geometric principles rather than statistical approaches to describe the likelihood of class membership. The so-called support vectors are a small portion of the training dataset and, using the input samples, SVM creates lines and hyperplanes to divide the data into classes for prediction. The values in one class that are closest to the other class and the separating line are the support vectors. The objective of SVMs is to maximizes the distance between classes, that is to say the distance between the support vectors. These are, in essence, the values that are hardest to categorize. The hyperplane mostly relies on a little number of observations. SVM use the kernel approach to identify a plane that partitions the data linearly in situations when it is not linearly separable. The kernel method's concept is to project the original features onto a space that is dimensionally bigger than the beginning space by generating nonlinear combinations of those features. It is therefore envisaged that at this stage the dataset becomes separable in the dimensionally bigger space. The Gaussian kernel, often known as the Radial Basis Function (RBF), is one of the most widely used kernels.

SVM is one of the easiest approaches to handle problem statements involving anomaly detection, and because one-class SVM can identify uncommon occurrences, it may also be utilized to identify new attacks in IDSs. While SVM is often resistant to noise, overfitting and a lengthy training period are potential drawbacks, along with a large number of parameters. Nonetheless, the one-class SVM classifier's strong outlier identification capacity makes it suitable for IDS. Fast and effective IDS is desired, while lengthy training times are not. To address these shortcomings, SVM may be adjusted in a number of ways, including dividing the data into smaller training sets and increasing the value of the radial kernel's parameter. IDS should be fast and efficient, but high training time is undesirable. SVM can be manipulated in several ways to improve these drawbacks, such as splitting the data into smaller training sets or using a higher value for the parameter in the radial kernel.

4.6. Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)

Artificial Neural Networks are capable of performing a wide range of tasks, including data categorization and classification through training to approximate any function. A directed graph is used by feed forward neural networks (FFNs), a type of artificial neural network (ANN), to transfer different system information from one node to another without creating a loop. An example of an FFN with three or more layers is the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) model, which consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Numerous neurons or units make up each layer. With all of the neurons in each layer completely linked, information is transferred forward from one layer to the next. Usually, weighted connections connect every neuron in the following layer to every other neuron. Usually, weighted connections connect every neuron in the following layer to every other neuron. Each neuron sums the weighted values of all the neurons connected to it and adds a bias value. This result is then subjected to an activation function, which merely performs a mathematical transformation on the value before forwarding it to the subsequent layer. The node transmits the value on to the next layer if the operation's value is greater than the anticipated threshold; if not, zero is sent on. Neural networks are designed to be universal function approximators; hence, a non-linearity component, or activation function, must be introduced. The input values are sent to the output neurons via the network in this manner. The many connections among neurons inside a neural network (NN) therefore take the shape of a weighted oriented graph, where the edges represent the weighted connections among neurons, the nodes represent individual neurons, and the direction of the edges represents the direction of signal propagation. Processing an input data means sending a stream of information across that graph, which is periodically changed by the weights and activation functions of the neurons. MLP is mathematically defined as

where

is the size of the input vector

and

is the size of the output vector

respectively. The calculation of each hidden layer

is defined mathematically as

, where

,

,

,

,

denotes the size of the input,

is the nonlinear activation function, which can be either the sigmoid function (values in the interval [0, 1]) or a tangent function (values in the interval [1, -1]). For the multi-class classification problem, the MLP model can use the softmax function as the nonlinear activation function. The softmax function outputs the probabilities of each class. There are many possible activation functions, the typical ones are presented in (5-8).

The Rectifier Linear Unit, or ReLU, function is one of the most often utilized activation functions among them, particularly in intermediate layers. Its effectiveness and propensity to speed up training can be attributed to its straightforward computation, which flattens the negative values to zero and leaves everything unchanged for values greater or equal to zero. It is considered to be the fastest and least expensive way to train large amounts of data when compared to traditional nonlinear sigmoidal and tangent activation functions.

Since the purpose of the network is to minimize the prediction error of the output from the expected value of the data, it is necessary to calculate this error and proceed backward along the oriented graph to calibrate the weights according to how much they affected the erroneous output. The principle behind error minimization in ANNs with supervised learning is gradient descent. Gradient descent is a technique that aims to minimize the loss function as much as possible. The backpropagation algorithm calculates the gradient of the loss function with respect to the network weights for a single input-output example and does so by calculating the gradient one layer at a time, backward from the outputs to the inputs to derive by how much the weights need to be changed one by one. In general terms, for many hidden layers, the MLP is formulated as follows: . This way of stacking hidden layers is generally called deep neural networks (DNN).

4.7. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

An advanced form of artificial neural network (ANN) called a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [

19] is used to handle grid topology input, such sequences or pictures. CNNs are capable of processing one-, two- and three-dimensional data. CNNs architecture aims to resemble the multiple-layered neurons seen in the human visual system, each of which is in charge of identifying a distinct feature in the data. Through the application of pertinent filters, a CNN may effectively capture dependencies (spatial and/or temporal) in the data, resulting in a good internal representation of the world. A CNN typically consists of pooling and convolutional layers that alternate. The name "convolutional neural network" indicates that the network uses a mathematical operation called convolution, a specialized type of linear operation that consists of the application of a sliding window function (also known as kernel or filter) to a matrix of pixels representing an image. An application of multiple convolutional layers allows to pass from low-level features to high-level features. Following every convolution process, a ReLU activation function is performed. By teaching the network nonlinear relationships between components in the picture, this function strengthens the network's ability to recognize various patterns. Usually applied after a convolution layer, which extracts the most important features from the convolved matrix, the pooling layer is a downsampling technique. This is accomplished by using an aggregation procedure to shrink the size of the convolutional matrix, or feature map, which lowers the amount of memory required for network training. Pooling is important to reduce overfitting as well. Max pooling, average pooling, and sum pooling are the three most often used aggregating functions.When the pooling function is used, the size of the feature map decreases. The feature map is flattened by the last pooling layer so that the fully linked layer can analyze it. The convolutional neural network's last layer has fully connected layers, whose inputs match the one-dimensional matrix that has been flattened by the final pooling layer. The final predicted label is the one with the greatest probability score. ReLU activation functions are employed here, and a softmax prediction layer is used to calculate probability values for each of the potential output labels. Filter weights, which are defined at each convolutional level, are established during the training stage by an iterative update procedure. That is, they are first initialized and then adjusted by backpropagation to minimize a cost function.

4.8. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gate Recurrent Unit (GRU)

There are two distinct varieties of recurrent neural networks (RNNs): LSTM [

32] and GRU [

33]. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) have more processing options than simple neural networks like Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs). RNNs have the ability to go through several levels and to store data momentarily for use at a later time.

A method called backpropagation is used to train the RNN model: let

be the RNN model's input.

is a representation of the connection weights between the input

and the first hidden (current) layer.

indicates the link weight between the current hidden layer and the subsequent hidden layer.

is a representation of the weight between the last hidden layer and its matching output layer. Let

be the output at time

. In particular,

and

reflect the biases introduced to the connections between the hidden layer and the output layer. The predicted outcome is denoted by

, and an RNN is mathematically constructed as illustrated in (9).

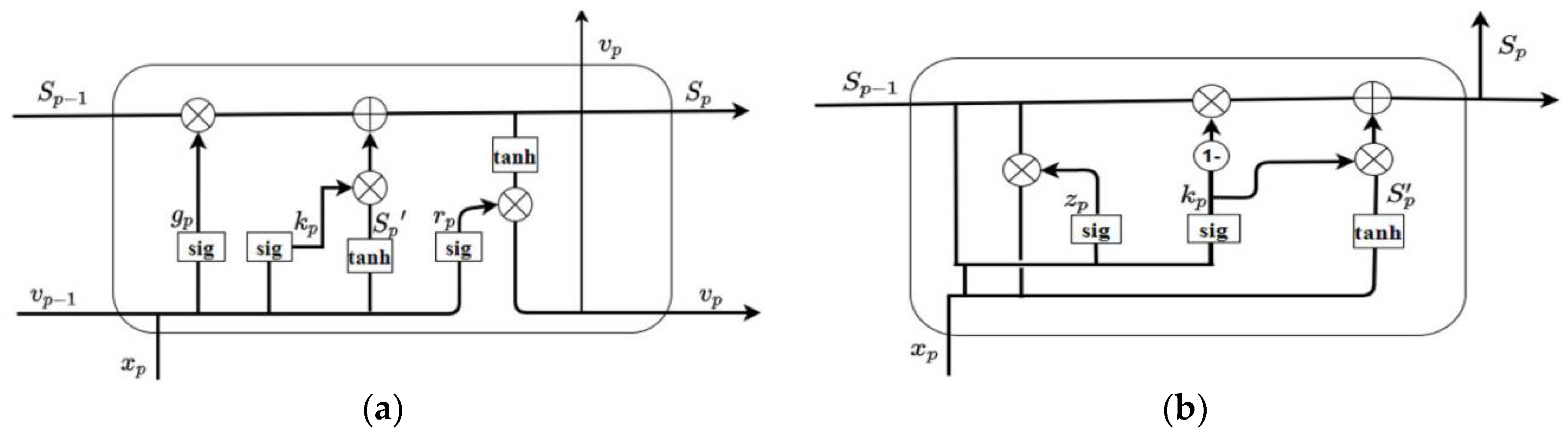

Although RNNs are effective in performing various prediction tasks, they nevertheless have a problem of exploding and vanishing gradients. To solve this problem, other types of RNNs such as Long-Short Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) have been designed. More specifically, the LSTM (illustrated in

Figure 1(a)) operates as defined in (10); GRU (illustrated in

Figure 1(b)) operates as defined in (11).

S denotes the state of the cell,

denotes the calculated prevision,

is the update function. The following activation functions are used in both LSTM and GRU units: hyperbolic and sigmoid tangent, whose formulas are illustrated in (12) and (13).

5. Datasets

A classifier is trained using a ML algorithm on a dataset of typical and anomalous traffic patterns in a machine learning technique. Subsequently, a trained model may be used to instantly identify suspect traffic. While there are certain drawbacks to such systems, their primary benefits lie in their capacity to learn without explicit programming and their flexibility in responding to changing traffic patterns. The security of a contemporary A-NIDS employing ML methods depends on the choice of a training dataset.

In this section, the selected datasets are illustrated and described. The datasets are KDD CUP 99 Dataset (KDD-99), NSL-KDD Dataset, USW-NB15 Dataset and IoT-23 Dataset. The choice fell on these datasets because, from the state-of-the-art analysis:

On the NSL-KDD dataset, whenever feature selection is used, classification performance can be improved. In addition, the RF algorithm is very effective on this dataset and reports high performance results. DT also seems to perform well on this dataset;

On the KDD-99 dataset, whenever feature selection is used, the improvement in classification performance was not always discounted. However, RF works very well on this dataset;

On the UNSW-NB15 dataset, feature selection is effective in improving classification performance. CNN and recurrent patterns are a successful approach on this dataset, in fact, being a large dataset, deep learning seems to be the solution.

5.1. KDD CUP 99 (KDD-99) Dataset

KDD-99 has been the most used dataset for testing anomaly detection techniques since 1999. It was prepared by [

34] and is a variation on the dataset that was initially developed as part of an IDS initiative at MIT's Lincoln Laboratory. The program was tested in 1998 and again in 1999. The DARPA-funded program yielded what is often known as the DARPA98 dataset. The dataset that is known as the KDD CUP 99 dataset was subsequently refined for the International Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining Tools Competition. Five million connection records over the course of seven weeks of traffic were utilized to create a training set. Another two weeks of network traffic generated a test set with two million examples. KDD-99 is a filtered version of this data.

Table 1 shows the classes distribution, resulting from a pre-processing phase, where redundant data points were discarded (78% of training set and 89.5% of test set). The training set originally comprised 4,898,431 data points but it was reduced to 1,074,992 unique data points. Similarly, the test set has been reduced from 2,984,154 to 311,029.

The classes are:

Normal;

Denial of Service Attack (DoS): DoS attack, occurs when an attacker prevents authorized users from accessing a system or overloads certain computer or memory resources, making them unable to process valid requests;

Probing Attack: These attacks involve scanning the network to identify valid IPs, and information is collected on those IPs. Often this information provides attackers with a list of vulnerabilities that can later be useful in launching attacks on systems and services;

Remote to Local Attack (R2L): the term refers to the process by which a malicious user who is able to transmit packets to a computer on a network but does not have an account on that machine uses a vulnerability to obtain local access as that machine's user;

User to Root Attacks (U2R): they are a type of exploit where the attacker gains root access to the system by first getting access to a regular user account (perhaps by password sniffing). From there, they can take advantage of a vulnerability.

Each pattern has 41 features, assigned to one of three categories: Basic, Traffic, and Content:

Basic features: this category encompasses all attributes that can be extracted from a TCP/IP connection;

Traffic features: this category includes features computed with respect to a window interval and is divided into two groups: (a) "same host" feature: in order to compute statistics pertaining to protocol behavior, service, etc., it focuses only on connections made within the last two seconds that share the same destination host as the active connection; (b)"same service" feature: it only focuses on connections that have had the same service as the current connection for the previous two seconds. The above two types of "traffic" features are called time-based. However, there are several slow probe attacks that scan hosts (or ports) using a much wider time window than 2 seconds, such as one every minute. As a result, these attacks do not produce intrusion patterns with a time window of 2 seconds. To solve this problem, the "same host" and "same service" features are recalculated based on a connection window of 100 instead of a 2-second time window. These features are called connection-based traffic features.

Content features: R2L and U2R attacks lack the regular sequential patterns of incursion that characterize typical DoS and probing attacks. This is due to the fact that R2L and U2R attacks are encoded in the data portions of packets and often only require a single connection, whereas DoS and Probing attacks entail several connections to certain hosts in a very short amount of time. Certain aspects are necessary to be able to search for unusual activity in the data section, such as the number of unsuccessful login attempts, in order to detect these kinds of attacks. These features are called content features.

The unbalanced nature of the dataset is evident from the

Table 1: 98.61% of the data belongs to the Normal or DoS categories. Moreover, the non-stationary nature of the KDD-99 dataset is visible from the distributions of training and test data in the

Table 1: 23% of the training set consists of DoS examples versus 73.9% in the test set; Normal is 75.61% in the training set but only 19.48% in the test set.

5.2. NSL-KDD Dataset

Unfortunately, KDD-99 has a number of drawbacks that may deter its application in the current setting, such as its advanced age, non-stationarity in training and test datasets, redundant patterns, and extraneous features, therefore NSL-KDD has been introduced [

35]. The goal of NSL-KDD is to improve KDD-99. The dataset is nevertheless vulnerable to several issues, as the authors point out, such as its inability to adequately depict low-impact assaults but, compared to KDD-99, the number of unique data points in NSL-KDD is less than that of KDD-99. As such, the training phase requires less computing power. NSL-KDD includes sub-sampling of the Normal, DoS and Probe classes. This mitigates some of the problems associated with the asymmetry of KDD-99. Therefore, NSL-KDD is a stationary sampling of KDD CUP 99.

5.3. UNSW-NB15 Dataset

A more recent substitute for KDD-99 is the UNSW-NB15 dataset [

36]. Its features and generating process are similar enough to KDD-99 and can be considered a competitive replacement, and it compensates few of the drawbacks that make KDD-99 difficult to employ in modern NIDS. This dataset was simulated by monitoring the traffic of two days in 16-hour and 15-hour sessions using the IXIA PerfectStorm program, at the Australian Center of Cyber Security (ACCS). Compared to 11 IP addresses on 2 networks for KDD-99, 45 distinct IP addresses over 3 networks were used for the UNSW-NB15. The attacks were selected from an up-to-date CVE site; normal behavior was not replicated. TCPdump collected communications at the packet level. 2,540,044 recordings in total were produced. To split the UNSW-NB15 into training and testing data, a significantly smaller division was chosen. Ten target classes (whose distribution is displayed in

Table 2) are included in NB15:

Normal;

Fuzzers: trying to stop a program or network by feeding it data that is produced at random;

Analysis: it includes several attacks to port scan, spam attacks, and HTML file penetration kind of attacks;

Backdoors: a method for secretly bypassing a system security measure to access a computer or its contents;

DoS: an intentional attempt to prevent people from accessing a server or network resource, often by momentarily stopping or disrupting the operations of a host that is connected to the Internet;

Exploits: the attacker takes advantage of a known vulnerability;

Generic: a method that functions against all block ciphers (with a specific block and key size) without taking the block cipher's structure into account;

Reconnaissance: includes every strike that can imitate an information-gathering attack;

Shell code: a small piece of code used as the payload in the exploitation of software vulnerability;

Worms: malware that replicate themselves in order to infect more systems. It frequently spreads over a computer network, taking advantage of security flaws in the target machine's security to gain access.

49 features were extracted using tools such as Bro-IDS and Argus. In addition, these features were classified into five categories: Basic, Flow, Time, Additionally Generated and Content. We highlight the uniformity of UNSWNB15 compared to traditional datasets by observing the target-largest-to-smallest ratio in the next figure. KDD-99 is the most unbalanced. NSL-KDD attempts to alleviate this problem. The asymmetry of UNSW-NB15 is significantly lower. Data stationarity is maintained between the training and test sets in NB15, in which both have similar distributions.

5.4. IoT-23 Dataset

The IoT-23 dataset [

37] was collected at the Stratosphere Laboratory at Czech Technical University between 2018 and 2019 and aims to facilitate researchers in their attempts of developing machine learning models.

IoT-23 contains a total of 23 traffic traces, or PCAP files known as scenarios, that were collected in an IoT network environment that was under control and had an unrestricted network connection: three of the traces correspond to benign traffic, and twenty to malicious activity. Each scenario is more specifically associated with a particular malware sample or benign traffic. The benign scenarios were collected by recording the network traffic of three distinct real IoT devices: a Somfy smart lock, an Amazon Echo smart home personal assistant, and a Philips HUE smart LED light; this allowed to track actual typical network data, instead of simulated traffic data. The malicious traffic was produced by an infected Raspberry Pi. Details such as length, number of packets, number of Zeek streams, pcap file, and device name are provided for each of these devices.

The labels used for detecting malicious network flows are:

Attack: this label denotes the existence of an attack originating from the compromised device and directed against a different host. For instance, a command injection into the header of a GET request, a brute force attempt at a telnet login, etc.;

Benign: this label indicates that no suspicious or malicious activity was detected in the connections;

C&C: this label denotes that a Command&Control server was linked to the compromised device. Because of the irregular connections to the suspicious server or the sporadic arrival and departure of certain IRC commands, this behavior was discovered during the network malware capture analysis;

DDoS: the volume of traffic flowing to the same IP address indicates that these flows are part of a DDoS assault;

FileDownload: this label denotes the process of downloading a file to the compromised device. This is identified by screening connections whose response bytes exceed 3 KB or 5 KB; often, this is done in conjunction with a destination IP or port that is known to be a C&C server and to be suspicious;

HeartBeat: This label denotes that the C&C server tracks the infected host using packets transmitted over this connection;

Mirai: this label denotes that the C&C server tracks the infected host using packets transmitted over this connection;

Okiru: Connections with this designation exhibit traits of an Okiru bot-net. The only distinction being that this botnet family is less widespread than Mirai when it comes to the labeling choice

Mirai: this label reports that the connections resemble a Mirai botnet. It was discovered by filtering connections with response bytes less than 1B and similar periodic connections. Usually, this is combined with the destination port or destination IP that happens to be a C&C server. When flows exhibit patterns like the most prevalent known Mirai assaults, this label is appended;

PartOfAHorizontalPortScan: This label denotes the use of connections for a horizontal port scan in order to get data for further attacks. These labels are used to patterns in which connections have numerous distinct destination IP addresses, the same port, and a comparable amount of transferred bytes;

Torii: This descriptor denotes that the connections exhibit traits of a botnet associated with Torii. The criteria used for this categorization determination were the same as those used for Mirai, with the exception that this botnet family is less widespread.

The three most frequent malicious (non-benign) la-bels among the 20 malware captures are DDoS (19,538,713 flows), Okiru (47,381,241 flows), and PartOfAHorizontalPortScan (213,852,924 flows). However, C&C-Mirai (2 streams), PartOfAHorizontalPortScan-Attack (5 streams), and C&C-HeartBeat-FileDownload (11 streams) are the three least frequent malevolent (non-benign) labels.