1. Introduction

Obesity incidence has become arguably the most serious global public health issue of the modern era. To combat the problem, international health organisations stress the importance of ongoing, comprehensive care that is coordinated across a multidisciplinary team (MDT) [

1,

2]. However, managing mid- to long-term regular consultations in real-world face-to-face (F2F) settings has historically been challenging for anyone with significant work or family commitments [

3,

4]. In countries with large regional populations such as the USA and Australia, many people living with obesity face an additional geographic barrier to quality care [

5].

As a result of these access issues, multiple digital weight-loss services (DWLS) have started to emerge. Several of these services are comprehensive, coordinating behavioural and pharmacological therapy through MDTs, such as Ro in the USA and Eucalyptus in Australia, Germany, Japan and the UK [

6,

7]. However, most countries with DWLSs have a broad care model spectrum, with those at the minimalist end offering little more than access to scripts for weight-loss medications, including Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) [

8]. And while clinical trials have consistently found GLP-1 RAs to be safe and highly effective in weight-loss cohorts [

9,

10], medical institutions continue to raise reasonable questions about the way DWLSs provide them. Namely, they appear concerned that certain DWLSs have inadequate safety protocols and allow people unsuitable for GLP-1 RAs to obtain such medications [

7]. Errors of this nature ultimately stem from one of two phases in the commencement of a patient’s care journey: the prescribing phase or the dispensing phase.

Scholarly interest in medication errors appears to have risen over the past decade, some of which may be attributable to the World Health Organization’s ‘Medication Without Harm’ campaign in 2017 [

11]. However, in Australia, most of this research focuses on prescription phase markers, such as preventable medication-related hospitalisations [

12,

13], adverse event figures [

14] and inappropriate prescribing incidence [

15,

16]. To our knowledge, only one Australian peer-reviewed study on dispensing error rates has been published in the past decade – a 2015 study that detected an error rate of 11.5% in 3959 dose dispensing aids used in 45 aged care facilities [

17]. Notably, a 2019 national

Medicine Safety report from the University of South Australia and Pharmaceutical Society of Australia was unable to contribute dispensing error data despite acknowledging its critical role in reducing medication-related harm [

18].

The best available benchmark for general dispensing safety appears to come from a global meta-analysis published earlier this year. The Um et al. (2024) meta-analysis pooled data from 62 studies across community, hospital and other pharmacy settings and concluded that the worldwide prevalence of dispensing errors was 1.6% [

19]. However, the study reported a dispensing error range from 0 to 33%, which is consistent with earlier meta-analyses and likely reflects considerable variance in pharmacy setting, technology use and study methodology [

20]. In addition to the uncertainty around general dispensing error rates in Australian care settings, little is known about the degree to which digital modalities impact dispensing safety, both in Australia and the rest of the world. Studies have demonstrated that electronic prescribing typically reduces medication error rates (thus, combined prescription, dispensing and administration errors) in hospitals [

21,

22], but none appear to have analysed the impact on dispensing in isolation, let alone in non-hospital settings. Only one study in the Um et al. (2023) meta-analysis assessed the safety of a remote service, reporting a slightly higher dispensing error rate (1%) in a telepharmacy site versus a community comparator [

23].

This study aimed to analyze the dispensing error rate of Australia’s largest comprehensive DWLS provider, Eucalyptus. Previous studies have reported on the effectiveness, adherence rates, and utility of the Eucalyptus DWLS and suggested the need for focussed investigations of the service’s clinical governance system [

4,

7,

24,

25]. Similar to other comprehensive DWLSs, Eucalyptus outsources GLP-1 RA dispensing to external partner pharmacies to enhance the service’s efficiency. As such, this study is assessing an aspect of the Eucalyptus DWLS care model that is unique to traditional care models but representative of the burgeoning field of digital chronic care. While there does not appear to be an obvious benchmark for comparison, this study’s findings should give an intuitive preliminary insight into the degree to which real-world DWLSs can safely collaborate with third-party pharmacies to dispense GLP-1 RAs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This adopted a retrospective case study design to analyse a dataset of patients enrolled in the Juniper (women) or Pilot (men) Australia (both owned by Eucalyptus) weight-loss programs between 1 June 2023 and 1 December 2023. This method was selected in accordance with the NHS Health Research Authority’s ‘Defining Research table’ [

26], having satisfied the following criteria: “designed and conducted solely to define or judge current care or service”; “measures current service without reference to a standard”; “involves analysis of existing data”; and “patient/service user have chosen intervention independently of the service evaluation”. Bellberry Limited approved the ethics of this study on 22 November 2023.

2.2. Program Overview

The Juniper and Pilot DWLSs have received accreditation through the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards and the UK Digital Technology Assessment Criteria. Both deliver combined GLP-1 RA therapy and asynchronous health coaching via a mobile app and digital platform. All patients are allocated an MDT, consisting of a doctor, a university-qualified health coach, a pharmacist and a medical support officer to guide them through a personalised weight-loss program. Doctors determine patient eligibility for the Eucalyptus DWLS from pre-consultation questionnaires, which can contain over 100 questions, including requests for test results and photos.

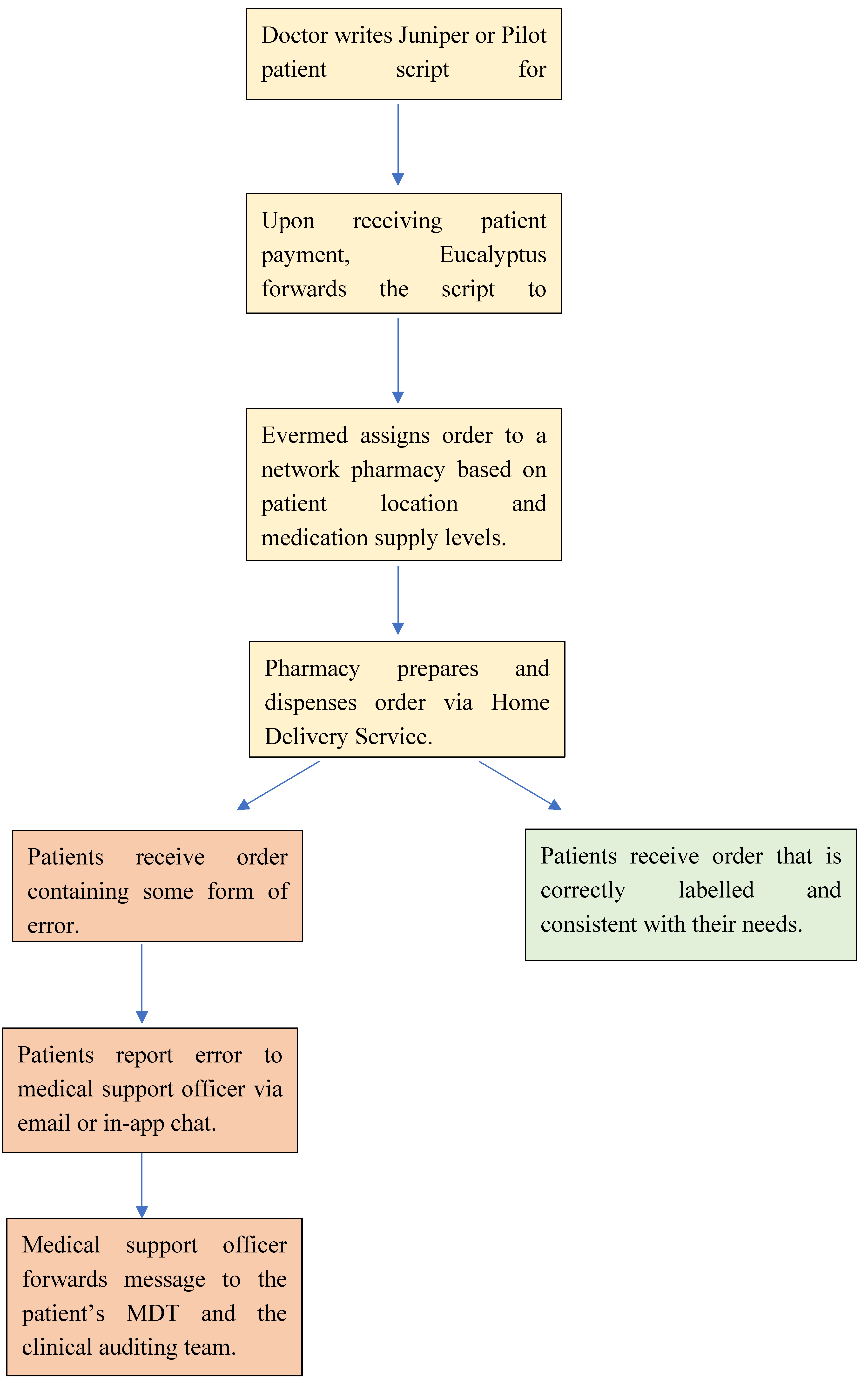

Eligible patients are then provided with a GLP-1 RA script. Upon receiving payment for the weight-loss program, Eucalyptus forwards the patient’s script to the Evermed pharmacy network, who then assign the order to one of its community pharmacies. Pharmacy selection is based on medication supply levels and geographic location relative to the patient, and orders are dispatched within 24 hours via Home Delivery Service, a large Australian delivery provider. All Juniper and Pilot patients are clearly instructed to inform their medical support officer via email or the programme’s in-app chat feature if the pharmacy makes any form of error (e.g., distributed the wrong medication, labelled the order incorrectly). Reported errors are forwarded by medical support officers to the patient’s MDT who consults the patient on the appropriate course of action. All error-related communications between patient, medical support staff and clinicians are also forwarded to the Eucalyptus clinical auditing team who store pharmacy error data in Jira. Throughout the study period, Semaglutide was the only GLP-1 RA medication prescribed to Eucalyptus Australia DWLS patients. All patients received 4 Semaglutide syringes per order. A flow chart of the Semaglutide dispensing process can be viewed in

Figure 1.

2.3. Participants

The study’s cohort comprised all Juniper and Pilot weight-loss patients who received at least one Semaglutide order between 1 June and 1 December 2023. Patient eligibility for either program was determined by an Australian doctor, who followed the Ozempic product information guidelines for weight-loss therapy.

2.4. Procedures

Study data were retrieved from the Eucalyptus clinical auditing team’s issue tracking repository on Jira. The Eucalyptus clinical auditing team filtered all pharmacy errors reported by Juniper and Pilot weight-loss patients between 1 June and 1 December 2023 on Jira and extracted them onto an csv spreadsheet for the study authors’ analysis. The total number of Eucalyptus Semaglutide orders from the same 6-month period were used as the denominator.

2.5. Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the dispensing error rate, which was calculated by dividing the total number of dispensing errors by the total number of Semaglutide orders. Error type (

Table 1) and error urgency rating (

Table 2) frequencies represented the study’s secondary endpoints.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

A chi-square test was conducted to test for statistically significant differences between the two Eucalyptus Australia DWLS’, i.e., the difference between female-reported and male-reported dispensing error rates.

3. Results

Between 1 June and 1 December 2023, Eucalyptus dispensed 135131 Semaglutide orders, including 107477 to female patients and 27654 to male patients. Within this period, 191 errors related to the dispensing of Semaglutide were reported, representing an error rate of 0.14%. A higher dispensing error percentage was observed among the female (Juniper) cohort (0.16%) compared to male (Pilot) patients (0.076%), which a Chi-square test revealed to be statistically significant, X2 (2, N = 135131) = 10.54, p = 0.001.

Non-compliant dose escalation (44.5%) and dispatch errors (32.5%) were the two most common error types (

Table 3). The vast majority of errors (89%) were deemed to have been of medium urgency, with 6.8% coded by the Eucalyptus auditing team as high urgency. A disproportionate number of high urgency cases were from wrong medication (31%) and general complaint errors (15%). All results are presented in

Table 3.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to report dispensing error rates in a GLP-1 RA-supported DWLS. Such services are becoming increasingly important throughout the world, as they arguably represent the most accessible means of managing chronic conditions like obesity which require continuous multidisciplinary care. And while the development of GLP-1 RA medications has shown early promise in shifting the alarming trajectory of global obesity rates, the potential for harm in the provision of such medications through irresponsible DWLSs should not be underestimated. Establishing a foundation for dispensing error rates in DWLSs, or simply modern digital chronic care settings in general, represents a vital step towards mitigating harm in modern weight-loss patients

The 0.14% dispensing error rate observed in the analysis appears low relative to the available literature. However, as was discussed in the background section, current data does not lend itself to clear comparison with dispensing error frequency in a DWLS. The only available Australian study on dispensing error rates was conducted in aged care services – a setting renowned for its high medication error rate. And although the recent Um et al. (2023) meta-analysis gives a good indication of global dispensing error standards, only one study assessed a remote service, which in 2003, would have looked very different from a modern digital care service. It is reasonable to conceive of health stakeholders holding all care modalities to the same dispensing safety standard when data becomes more readily available. Until such time, it is difficult to evaluate the dispensing safety level of the Eucalyptus DWLS observed in this study.

The study’s secondary endpoints shed light on some important considerations for DWLSs. The relatively high prevalence of non-compliant dose escalation errors suggests a need for stricter dose monitoring protocols and better patient education processes. While it could be argued that health practitioners have a lower degree of control over this error type compared to other error types, the onus is on DWLSs to develop a mechanism for reducing this risk. Without such a mechanism, it is feasible that the risk of non-compliant dose escalation could increase commensurate to the hype of DWLSs. Furthermore, although analysis of the clinical response to high urgency errors was beyond the scope of this study, the discovery that over 15% of high urgency errors were related to patient complaints suggests the company’s clinical auditing team also had an eye on commercial concerns. This could be interpreted as a potential weakness of the service’s dispensing safety protocols, given the typical efficiency demands of private companies.

It could be reasonably assumed that deeper collaboration between Eucalyptus’ prescribing practitioners and its pharmacists would also lower the company’s Semaglutide dispensing error rate. Although the company’s DWLS is holistic and connects patients with coordinated MDTs,

Figure 1 demonstrates the lack of involvement of the service’s practitioners across the Semaglutide dispensing phase. Integrating pharmacists and prescribing practitioners may represent a financial and logistical challenge for DWLSs that outsource either of these functions. However, ongoing research and development in the field of digital chronic care services should present robust solutions to this challenge.

The study’s strengths included its sample size, its broad inclusion criteria, it’s non-interference with patient experiences, and its novelty. In terms of limitations, firstly, all data were self-reported, and thus subject to numerous patient biases and constraints. It is possible that the statistically lower dispensing error rate observed among males reflected the cohort’s relative apathy towards certain errors. Secondly, the potential effects of age, ethnicity or BMI category were not included in the investigation. And finally, the error and urgency categories could have benefitted from additional nuance.

The findings from this study lay a vital foundation for ongoing research on dispensing safety in DWLSs and digital care in general. Despite the soaring uptake of GLP-1 RA-supported DWLSs in recent years, literature on the safety of such services remains scarce. GLP-1 RA dispensing errors represent one of the key dangers of such services, given both the relative potency of the medications and the outsourcing of their dispensation. This study’s findings suggest that comprehensive DWLSs have the potential to safely manage GLP-1 RA dispensing errors. They do not, however, refute the argument that DWLSs enable large numbers of unsuitable patients to obtain Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. To achieve such an end, further research is needed on dispensing and prescribing error rates of multiple comprehensive DWLSs.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, L.T. and M.V.; methodology, L.T and M.V; validation, L.T and M.V.; formal analysis, L.T and M.V..; investigation, L.T.; resources, M.V.; data curation, L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T..; writing—review and editing, L.T & M.V; supervision, L.T.; project administration, L.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review board (or ethics committee) of the Bellberry Ethics Committee (No. 2023-05-563-A-1, 22 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Eucalyptus patients consented to the service’s privacy policy at subscription, which includes permission to use their de-identified data for research.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Eucalyptus clinical auditing team for their work over the study period.

Conflicts of Interest

LT and MV are paid a salary by Eucalyptus.

References

- World Health Organisation. Health service delivery framework for prevention and management of obesity. Geneva 2023.

- Yumuk, V. , Tsigos, C., Fried, M., et al. European guidelines for obesity management in adults. Obes Facts 2015, 6:406-424.

- Asselin, J. , Osunlana, A., Ogunleye, A., et al. Challenges in interdisciplinary weight management in primary care: lessons learned from the 5As Team study. Clin Obes,2016 Apr; 6(2):124-132.

- Talay, L. , Vickers, M., Loftus, S. Why people with overweight and obesity are seeking care through digital obesity services: a qualitative analysis of patients from Australia’s largest digital obesity provider. Telemedicine Reports, 2024 (in press).

- Washington, T. , Johnson, V., Kendrick, K., et al. Disparities in access and quality of obesity care. Gastroentrol Clin North Am 2023 Apr; 52(2): 429-441.

- Lopatto, E. Who wins when telehealth companies push weight loss drugs? The Verge. October 23, 2023. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/23878992/ro-ozempic-subway-ads-telehealth-weight-loss-drugs.

- Talay, L., & Vickers, M. Patient Adherence to a Real-World Digital, Asynchronous Weight Loss Program in Australia That Combines Behavioural and GLP-1 RA Therapy: A Mixed Methods Study. Behavior Sciences, 2024;14:480.

- Talay, L. & Alvi, O. Digital healthcare solutions to better achieve the weight-loss outcomes expected by payors and patients. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 2024;26:2521-2523.

- Wilding, J., Batterham, R., Calanna, S., et al. Once-weekly Semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med 2021 Mar; 384: 989-1002.

- Jastreboff, A. , Aronne, L., Ahmad, N., et al. Tirzapetide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Eng J Med 2022 Jul, 387:205-216.

- World Health Organization. Medication without harm. 2017, Geneva. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/initiatives/medication-without-harm.

- Roughead, E. , Semple, S., & Rosenfeld, E. The extent of medication errors and adverse drug reactions throughout the patient journey in acute care in Australia. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2016 Sep; 14(3): 113-22.

- Lim, R., Ellett, L., Semple, S., et al. The extent of medication-related hospital admissions in Australia: A review from 1988-2021. Drug Saf 2022 Mar; 45(3) 249-257.

- Britt, H. , Miller, G., Henderson, J., et al. General practice activity in Australia 2014-15. General Practice series no. 40. Sydney: Sydney University Press 2016.

- Bakker, M., Johnson, M., Corre, L., et al. Identifying rates and risk factors for medication errors during hospitalisation in the Australian Parkinson’s disease population: A 3-year, multi-centre study. PLoS ONE 2022 May; 17(5): e0267969.

- Khanal, A. , Peterson, G., Castelino, R., et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing of renally cleared drugs in elderly patients in community and aged care settings. Drugs Aging 2015 May; 32(5): 391-400.

- Gilmartin, J. , Marriott, J., Hussainy, S. Improving Australian care home medicine supply services: Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention. Australasian Journal on Ageing 2016 Jun; 35(2):E1-E6.

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Medicine Safety: Take Care. Canberra, 2019.

- Um, I. , Clough, A., Tan, E. Dispensing error rates in pharmacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2024 January; 20(1): 1-9.

- James, L. , Barlow, D., McArtney, Hiom, S. et al. Incidence, type and causes of dispensing errors: a review of the literature. International journal of pharmacy practice 2009 Feb; 17(1):9-30.

- Roumeliotis, N. , Sniderman, J., Adams-Webber, T., et al. Effect of electronic prescribing strategies on medication error and harm in hospital: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2019 Oct; 34(10):2210-2223.

- Westbrook, J., Reckmann, Li, L., et al. Effects of two commercial electronic prescribing systems on prescribing error rates in hospital in-patients: a before and after study. PLoS Med 2012 Jan; 9(1): e1001164.

- Friesner, D. , Scott, D., Rathke, A., et al. Do remote community telepharmacies have higher medication error rates than traditional community pharmacies? Evidence from the North Dakota telepharamcy project. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 2003; 51(5): 580-590.

- Talay, L. & Vickers, M. Effectiveness and care continuity in an app-based, GLP-1 RA-supported weight-loss service for women with overweight and obesity in the UK: A real-world retrospective cohort analysis. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 2024; 26:2521-2523.

- Talay, L. , Vickers, M., Wu, S. Patient satisfaction with an Australian digital weight-loss service: A comparative retrospective analysis. Telemedicine Reports, 2024 (in press).

- Is my study research? National Health Service Health Research Authority. URL: https://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research/ [accessed 2023-01-07].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).