Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is an acute ischemic heart disease

with high morbidity and mortality, caused by rupture, ulceration, or erosion of atherosclerotic plaques of coronary arteries [

1]

. Globally, the incidence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), the main type of ACS, is increasing among the population aged 18-59 years [

2]

. In China, according to a relevant study, the number of patients with AMI is predicted to reach 75 million by 2030, with young and middle-aged patients accounting for about 50% [

3]

.

As a traumatic cardiac event [

4], ACS can trigger post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) [

5]

, including intrusive thoughts, avoidance, and negative alterations in cognition, etc [

6]

. About 12% of patients with ACS would experience clinically significant PTSS, which has been demonstrated to double the risk of recurrence or death of

ACS [

7]

. Furthermore, ACS could also cause emotional disorders, such as severe or mild depressive episodes, chronic depression, anxiety, and type A behavior, leading to poor quality of life and impaired function of patients [

8,

9]

. A cross-sectional survey showed that the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with ACS was 66.3% and 56.5%, respectively [

10]

. Although ACS is a stressful, challenging, and traumatic event, this difficult experience may promote personal growth for ACS survivors, known as post-traumatic growth (PTG) [

11]

. PTG refers to the positive changes that an individual makes in multiple aspects after struggling with a trauma, including an increased appreciation for life, more meaningful interpersonal relationships, an increased sense of personal strength, and a richer existential and spiritual life [

12,

13]

. PTG has been shown to occur in individuals experiencing AMI. In the study by Norekvål et al., the majority of female patients with AMI (65%) reported positive effects from AMI experience [

14]

. Zhou et al. reported moderate PTG levels in young and middle-aged patients with AMI [

11]

. Wang et al. conducted a potential profile analysis of PTG in young and middle-aged patients with AMI and showed that 18.91% belonged to the “Good growth group”, and 35.58% belonged to the “Excellent growth group” [

3]

. Patients who developed PTG were less likely to have recurrent AMI [

15]

and depressive symptoms, even had enhanced psychological well-being [

16]

.

In 2018, Tedeschi et al. proposed a revised model of PTG development [

17], and rumination is the central of this model. Rumination refers to the cognitive processing patterns of individuals after experiencing a traumatic event, including non-adaptive and adaptive rumination (or intrusive and deliberate rumination). Non-adaptive rumination occurs immediately after a traumatic event and leads to emotional distress such as anxiety, depression, and fear. This type of rumination occurs unintentionally and causes individuals to spend most of their time on it. Adaptive rumination enables individuals to make sense of life events, re-establish their beliefs, process the emotions they have experienced, and develop coping skills [

18]

. Zhou et al. reported moderate levels of rumination in young and middle-aged patients with AMI [

11]. Rumination is a predictor of PTSS and PTG [

19]. Non-adaptive rumination has been demonstrated to be associated with negative effects of trauma, such as dissociation state [

20], insomnia [

21], and depression [

22], etc. Trick et al. found rumination to be an independent predictor of depression in patients with ACS [

23]. On the other hand, adaptive rumination is a protective factor for PTG in young and middle-aged patients with AMI [

3]. The study by Zhou et al. demonstrated that adaptive rumination was positively correlated with PTG, and mediated the negative relationship between PTG and psychological adjustment in young and middle-aged patients with AMI [

11]. Thus, rumination can be intervened to promote the development of PTG.

To better develop a “framework of actions” for PTG interventions, many researchers have used qualitative methods to explore the content and forms of rumination in individuals who experienced traumatic events. Norekvål conducted qualitative interviews with 18 Norwegian elderly female patients with AMI on the nature of perceived positive effects of the disease, and extracted 4 themes: appreciating life (55%), getting health care (42%), making lifestyle changes (36%), and taking more care of self and others (29%) [

14]. However, rumination is influenced by age [

24] and social culture [

25], which implies that individuals of different ages or living in different sociocultural contexts may develop different rumination patterns from traumatic experience. In China, researches on rumination mostly conducted in patients with cancer, especially breast cancer. There have been no qualitative studies on rumination in young and middle-aged patients with ACS. Therefore, this study can fill this gap. This study aimed to explore the real experiences and feelings regarding ACS of young and middle-aged patients with ACS using qualitative research methods, to understand the content and nature of their rumination, thereby providing new data for the development of future intervention programs to promote PTG in these patients.

Materials and Methods

Design

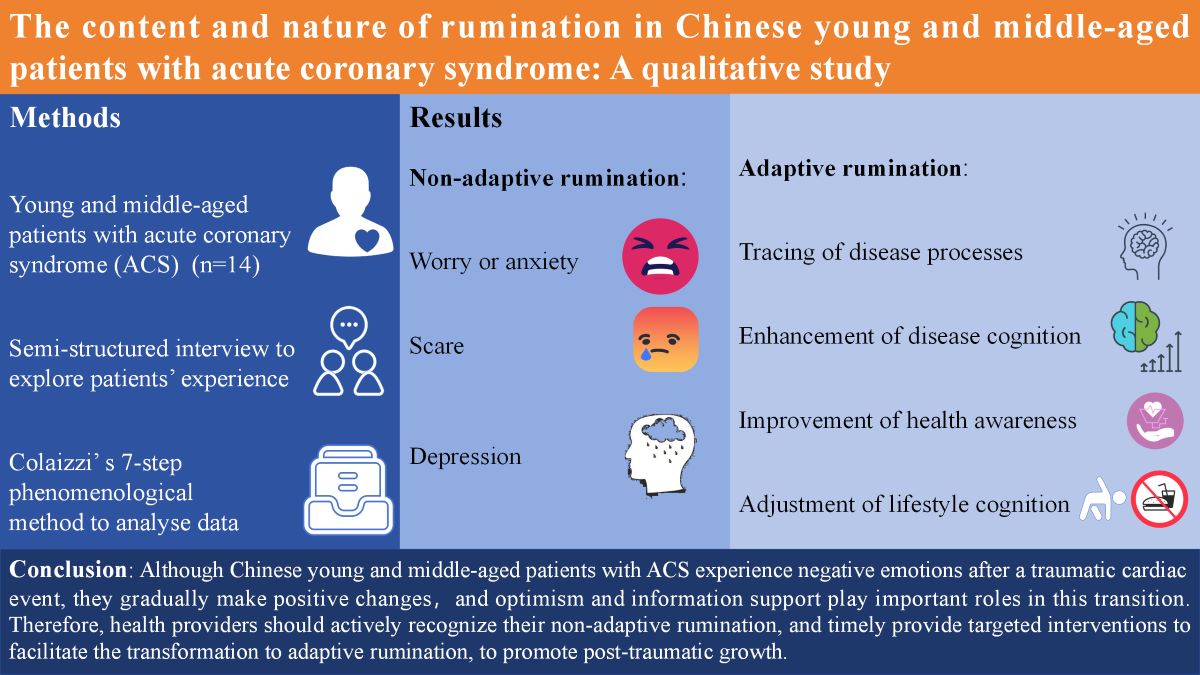

This study was a qualitative research and used the Colaizzi's phenomenological method to analyze data [

26]. The framework and reporting of this study followed Qualitative Research Reporting Integrated Standards (COREQ) reporting guidelines to ensure that sufficient details regarding the methods of data collection, analysis and interpretation were provided. This study had been approved by the Ethics Committee of Soochow University (SUDA20220922H02).

Participants

Participants were selected using the purposive sampling method in the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University from May 2023 to December 2023. Inclusion criteria were: (i) patients were diagnosed with ACS (i.e., unstable angina, ST-elevated myocardial infarction, and non–ST-elevated myocardial infarction); (ii) patients were 18-59 years old, with good cognition and communication skills; and (iii) patients who had stable condition and volunteered to participate in this study. Patients with severe life-threatening cardiac disease (e.g., cardiogenic shock, acute heart failure, and cardiac rupture), severe dysfunction of other organs, a history of psychiatric and psychological disorders, or malignant tumors were excluded. The sample size followed the principle of information saturation, resulting in the inclusion of 14 participants.

Interview Outline

Interview questions were designed based on relevant literature and expert opinions. Pre-interviews were conducted with 2 patients to determine the interview outline. The main interview questions were as follows: (1) Before the disease, what was your perception of the disease? (2) How did you feel at the beginning of the disease? (3) How did the disease affect you? (4) What were you most worried about? (5) After the disease, what was your perception of the disease? (6) How did you look forward to your future life through this experience? (7) What changes would you make to your life after discharge?

Interview

We conducted semi-structured interviews. All interviews were conducted in a private room to maintain participants’ privacy and psychological security. Before the start of an interview, all participants were informed of this study’s objectives and the voluntary nature of participation. Each participant signed a papery informed consent form and allowed audio recording of the interviews. Participants were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of the recordings, transcripts, and any behaviors observed during the interviews. At the beginning of an interview, participants were asked to provide demographic information (e.g., name, age, gender, educational level, occupation, etc.), as shown in Table 1. In order to ensure the privacy of the participants, numbers were used instead of their real names. Afterward, interview questions were asked to participants. During the interviews, the whole process was audio recorded simultaneously, and researchers listened to participants’ answers, observed their movements and expression changes, and made records. According to the interview outline and the actual situation of participants, researchers made flexible adjustments to the order and method of asking questions, without imposing any induction or intervention on participants or judging their any statements. An interview lasted for 20-30 minutes.

Data Analysis

The audio recordings were converted into texts within 24 hours after the interview. The data were analyzed using Colaizzi’s 7-step phenomenological method. (1) All interview data were carefully and repeatedly read to understand participants’ genuine experiences and feelings about ACS. (2) Important and meaningful statements related to the interview questions were identified and extracted. In this step, 93 meaningful statements about rumination were extracted. (3) Recurring ideas were coded. (4) The encoded ideas were pooled to look for meaningful common concepts to form the prototype themes. In this step, 7 themes were extracted. (5) Participants’ original descriptions were extracted to explain each formed theme in detail. (6) Similar ideas were identified and formal themes were sublimated. In this study, 2 categories were extracted. (7) Formed themes were returned to the participants for verification to ensure the authenticity of the results.

Results

Based on interviews with 14 participants, 7 themes and 2 categories were derived. 2 categories were non-adaptive rumination and adaptive rumination. Non-adaptive rumination included 3 themes: worry or anxiety, scare, and depression. Adaptive rumination included 4 themes: tracking of disease processes, enhancement of disease cognition, improvement of health awareness, and adjustment of lifestyle cognition.

Category 1. Non-Adaptive Rumination

Participants experienced a range of emotional distress in the early stages of ACS. In this category, 3 themes were derived: worry or anxiety, scare, and depression.

Theme 1. Worry or Anxiety

Some patients experienced worry or anxiety due to disease treatment, return to work, family responsibilities, economic pressure, etc.

N2: ‘I hear from doctors and nurses that I will take aspirin for a long time, and will need to pay attention to bleeding (the brow frowning)’.

N6: ‘I have learned from the Internet that coronary angiography agents cannot be excreted from the body and can cause fever and death (looking at the researcher anxiously)’.

N4: ‘I am worried about my wife and children (looking at his wife), and then after discharge, whether I can do my previous job, because I am a physical worker’.

N10: ‘What I worried about first is whether the disease will delay my teaching schedule in September, because I will go back to class (taking a deep breath)’.

N12: ‘Now that I am sick, so the family’s financial pressure suddenly becomes very heavy (tears infiltrating the eyes)’.

Theme 2. Scare

All patients lacked knowledge about ACS before admission. Some patients had previously disregarded the early symptoms of ACS or did not know the severity of the disease before, so that they were frightened by this fact after admission. Some other participants said they feared a sudden attack of myocardial infarction and death.

N8: ‘In fact, I had chest pains before, but I didn’t pay attention to it. Now I understand that this disease is really dangerous, and even can be life-threatening (a serious expression on face)’.

N12: ‘When the chest pained, I did not care about it. But after being in hospital, what I listened to the doctor said made me panic, and now I still feel a little scared’.

N13: ‘I once saw in the news that drivers in their 30s, 40s and 50s were died of sudden death, especially while driving, which resulted from heart attacks due to excessive fatigue. I am a driver, and I had chest pains several times while driving. Now I think about it, it is too dangerous (frightened eyes)’.

N11: ‘I do not know when the disease will attack, so I am afraid of a sudden acute attack and then die’.

Theme 3. Depression

Some patients experienced depressed emotions because they failed to adapt to the patient’s role quickly.

N11: ‘When I was first hospitalized for hypertension, the results of computed tomography and echocardiogram were good and my blood vessels and heart were in good condition. But after discharge, I noticed that I had chest pains and chest tightness, so I guessed it could be coronary artery disease. How can I have been diagnosed with coronary heart disease and hypertension at such a young age? What should I do (sighing and looking out the window)’?

N13: ‘I used to feel great about my body, but now I am sick so that I cannot do anything and cannot take care of my grandson (eyes are glazed)’.

N14: ‘I got sick for the first time last June and had a brace fitted. It has been almost a year and a half so far, and I think it will take more than ten years to get sick again, and I cannot be so unfortunate, but the fact is that the second hospitalization come so soon (bitterly smiling)’.

Category 2. Adaptive Rumination

From the onset of heart attack to stabilization after admission, participants recalled their traumatic experiences and searched for clues previously related to ACS. Subsequently, they actively searched for knowledge about ACS on the internet and carefully received health education from doctors and nurses. So, they were better informed about the disease and described their health plan after discharge. In this category, 4 themes were derived: tracing of disease processes, enhancement of disease cognition, improvement of health awareness and adjustment of lifestyle cognition.

Theme 4. Tracing of Disease Processes

All the participants traced their disease processes. They recalled what happened before and after admission and realized that in fact they had experienced early warning symptoms of ACS.

N2: ‘When I used to ride my bike, the more I rode, the powerful felt. But slowly I realized that I got out of breath easily when I rode uphill and also when I climbed hills. When I had an attack, my chest was uncomfortable, my throat was uncomfortable and tight, and I sweat (pointing to heart and throat)’.

N4: ‘I had a sudden attack of chest pains at night, and then transferred to the upper abdomen, with a lot of sweating and breathing difficulties, and then I asked my wife to make an emergency call immediately (the right hand gesticulating from the heart to the upper abdomen and frowning)’.

N13: ‘I had chest pains several times while driving’.

N14: ‘At the beginning, my chest was pained so that I could not sleep. After about an hour or two hours, I began to sweat’.

Theme 5. Enhancement of Disease Cognition

Participants said that they knew nothing about ACS or even never heard of it before they got sick, and after hospitalization, their cognition of ACS had enhanced to varying degrees.

N1: ‘I didn’t understand before, but now I know that I cannot make myself too tired and do heavy physical work’.

N2: ‘In the past, I just knew that one person I knew had died of a heart disease but I didn’t know anything about heart disease. When I am in hospital these days, I have learned a Mediterranean diet and low-salt and low-fat diet on the internet’.

N3: ‘Now I understand that people with irregular lifestyle, a family history of ACS, a heavy-oil and heavy-salt diet, alcohol consumption, and lack of exercise are more likely to develop myocardial infarction, of which the most common symptoms are chest tightness and chest pains’.

Theme 6. Improvement of Health Awareness

Many patients said that they knew that good health was important before, but they did not care about it. Their health awareness has been greatly improved after this experience of heart disease.

N3: ‘I used to enjoy drinking beverages, although I knew they were not good to health. But now I know that I must be self-disciplined, and I have a family history of heart disease, so I can not drink beverages anymore’.

N4: ‘I knew that smoking and drinking were bad to health before, but I always could not quit, and I didn’t take them seriously (smiled ashamedly). I must make up my mind to quit smoking and drinking after discharge. Health is so important, and I must put my health first’.

N6: ‘Now I will take my health seriously (clenched fist)’.

N14: ‘When I got sick the first time, I tried to exercise and quit smoking. But half a year later, when I returned to work, I gave up slowly and smoked more and more. But after being discharged this time, I dare not smoke anymore’.

Theme 7. Adjustment of Lifestyle Cognition

All participants said that they must change their bad living habits after discharge.

N2: ‘After discharge, I will keep exercising, live a regular life, not stay up late, and follow nurses’ advice of a low-salt and low-fat diet’.

N3: ‘Be sure to control my diet and exercise regularly, follow a diet with less oil and salt, drink less beverages, eat more vegetables and fruits, take in the right amount of protein, and keep a good mindset’.

N6: ‘I think I am so thin that after discharge I have to strengthen exercise to try to avoid a recurrence of heart disease’.

N10: ‘If I am in a bad mood or stressed, I will let it out instead of being in inner turmoil’.

N14: ‘After this discharge, I will take my medication regularly and not stop or take less medication without authorization’.

Discussion

This study used qualitative research methods to investigate the true feelings and experiences, and the content and nature of rumination in Chinese middle-aged and young patients with ACS. Two categories were extracted: non-adaptive rumination and adaptive rumination. Non-adaptive rumination included 3 themes: worry or anxiety, scare, and depression. Adaptive rumination included 4 themes: tracing of disease processes, enhancement of disease cognition, improvement of health awareness, and adjustment of lifestyle cognition. These findings provide a fundamental understanding of rumination experiences in Chinese young and middle-aged patients with ACS and provide new data for healthcare providers when designing intervention programs to enhance PTG in these patients.

After experiencing ACS, young and middle-aged patients showed negative emotional changes with characteristics of PTSD, similar to the results reported by Meli et al. [

27]

. There are three possible reasons. Firstly, the abruptness of the event, the actual risk of death, and the perceived loss of control and helplessness during the event represent potential trauma [

6]

. Intrusive thinking also focuses on the fear of future recurrent cardiac events, not just cardiac events that have already occurred [

28]. As some of the patients in the study said, they feared a sudden myocardial infarction and then death. Another patient who was hospitalized a second time for ACS said, he felt helpless about the second hospitalization. Secondly

, young and middle-aged patients are often the core of the family and the main workforce of society. After the diagnosis of ACS, patients will live with the disease for life, so they will likely bear a heavy burden in many aspects, such as expensive medical expenses, physical limitations, psychosocial maladjustment, risk of premature death, disharmonious family relationships, and the conflict between the roles of patients, families, and workers, etc [

3,

29]

. In this study, young and middle-aged patients with ACS experienced worry or anxiety, scare, and depression due to the worries about disease treatment and sudden death, economic pressure, inability to fulfill family responsibilities, inadaptation to the patient’s role, and the challenge of returning to work. Thirdly, there was a lack of disease-related knowledge. In this study, all patients were unaware of knowledge about ACS, which was similar to the results reported by Thanavaro et al.[

30]

. In interviews, one patient was worried about the long-term use of aspirin after discharge and its side effects, and another was worried about the side effects of contrast media used in coronary angiography. Some patients ignored the warnings or early symptoms of ACS and were scared after being admitted to the hospital and learning how dangerous the disease was. However, timely information support can alleviate anxiety, depression, and the psychological impact of the illness [

31]

. Therefore, it is imperative for medical staff to communicate more with patients to recognize their negative emotions.

Rumination is a dynamic process. Processes that initially run automatically (e.g., negative thoughts about experiences) are gradually replaced by an awareness of trying to find meaning in traumatic events and integrate these experiences into life [

32]. In addition, adaptive rumination will occur repeatedly even in the absence of direct demand, including 3 dimensions: past, present, and future, which can play an enduringly positive role in the development of individuals’ emotions, behaviors, and events [

33]. In this study, although young and middle-aged patients with ACS had negative emotions and lacked disease knowledge in the early stages of the disease, they slowly accepted the fact that they developed the disease, and they gradually obtained disease-related information from the Internet and medical staff. From the obtained information, they traced their disease processes to look for the causes and early warning symptoms of ACS, self-management knowledge, and other positive factors, and then gradually changed the original disease cognition, improved self-health awareness, and adjusted lifestyle cognition. This was similar to the cognitive processing that occurs in para-sport athletes after experiencing a disability life event [

34]. Therefore, medical staff should effectively identify the timing of the transition from non-adaptive to adaptive rumination in young and middle-aged patients with ACS, and provide patients with health education to help them better transit to adaptive rumination.

Positive cognitive processing is the result of the interaction of multiple factors. The results of this study showed that resilience and information support played important roles in the transformation of negative to positive cognitive processing in Chinese young and middle-aged patients with ACS. In this study, although the patients experienced some negative emotions, they did not overly fall into them, but maintained an optimistic attitude, calmed down and faced the disease, actively learned disease-related knowledge, and made positive adjustments. Resilience has been proven to be negatively correlated with non-adaptive rumination and be positively correlated with adaptive rumination [

35]. Computerized mouse-based (gaze) contingent attention training to improve resilience has been proven to reduce non-adaptive rumination effectively [

36]. Therefore, medical staff can take interventions to improve patients’ resilience to help them better deal with negative emotions and actively face the disease. It was not difficult to see from the interview data that patients in this study lacked relevant knowledge about ACS, regardless of education level. A study has shown that a lack of knowledge of ACS symptoms can delay decision making, in turn causing prehospital delay [

37]. Moreover, a high level of disease knowledge was correlated with less negative emotions and positive cognition and emotions [

38]. Besides, the lack of knowledge may also influence patients’ awareness of risk factors, health behaviors, and adherence to medication therapy [

31]

. In this study, after patients accepted the fact that they were diagnosed with ACS, they actively searched for information about ACS online and actively accepted health education from medical staff, and then gradually made positive adjustments. Therefore, medical staff should provide health education to patients and their families about ACS symptom recognition, treatment, risk factors, and self-management, to build patients’ confidence in fighting against the disease, improve their optimism level, and help them transit from non-adaptive rumination to adaptive rumination more quickly.

There were some limitations to this study. Firstly, the study was a short-term study, and the long-term experiences of the participants will be a valuable avenue for future exploration. Secondly, participants were all recruited from the same hospital. Therefore, multi-center and multi-stage qualitative studies are required to further investigate the content and nature of rumination in Chinese young and middle-aged patients with ACS in the future.

Conclusions

Although Chinese young and middle-aged patients with ACS experience negative emotions after a traumatic cardiac event, they gradually make positive changes. Optimism and information support play important roles in the transformation. Therefore, health providers should actively communicate with patients, recognize their non-adaptive rumination, and timely provide targeted interventions to facilitate the transformation to adaptive rumination, to promote PTG.

Author Contributions

Anan Li: Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. Yangfan Nie: Investigation; Writing – review & editing. Meixuan Chi: Investigation; Writing – review & editing. Naijuan Wang: Investigation; Writing – review & editing. Siying Ji: Investigation; Writing – review & editing. Zhaoying Zhu: Investigation; Writing – review & editing. Shan Li: Investigation; Writing – review & editing. Yunying Hou: Project administration; Supervision; Funding acquisition; Writing – review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version of the paper, and has not been previously published.

Funding

This work was supported by ‘2022.07-2025.06 Suzhou Science and Technology Program Project (Healthcare Science and Technology Innovation-Medical Innovation Applied Research)’ [grant numbers SKY2022102]. The sponsor was Yunying Hou.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Soochow University (SUDA20220922H02).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to restrictions of privacy and ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all the patients in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests.

Permission to Reproduce Material from Other Sources

No material was reproduced from other sources in our research.

References

- Bergmark, B.A.; Mathenge, N.; Merlini, P.A.; Lawrence-Wright, M.B.; Giugliano, R.P. Acute coronary syndromes. LANCET, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Behfar, A.; Narula, J.; Kanwar, A.; Lerman, A.; Cooper, L.; Singh, M. Acute Myocardial Infarction in Young Individuals. MAYO CLIN PROC. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Ke, Q.Q.; Zhou, X.Y.; Xiong, J.M.; Li, Y.M.; Yang, Q.H. Latent profile analysis and related factors of post-traumatic growth in young and middle-aged patients with acute myocardial infarction. HEART LUNG. [CrossRef]

- Akosile, W.; Colquhoun, D.; Young, R.; Lawford, B.; Voisey, J. The association between post-traumatic stress disorder and coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. AUSTRALAS PSYCHIATRY. [CrossRef]

- von Känel, R.; Meister-Langraf, R.E.; Barth, J.; Schnyder, U.; Pazhenkottil, A.P.; Ledermann, K.; Schmid, J.P.; Znoj, H.; Herbert, C.; Princip, M. Course, Moderators, and Predictors of Acute Coronary Syndrome-Induced Post-traumatic Stress: A Secondary Analysis From the Myocardial Infarction-Stress Prevention Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial. FRONT PSYCHIATRY, 6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Princip, M.; Ledermann, K.; von Känel, R. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder as a Consequence of Acute Cardiovascular Disease. CURR CARDIOL REP. [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, D.; Richardson, S.; Falzon, L.; Davidson, K.W.; Mills, M.A.; Neria, Y. Posttraumatic stress disorder prevalence and risk of recurrence in acute coronary syndrome patients: a meta-analytic review. PLOS ONE, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostoli, S.; Buzzichelli, S.; Guidi, J.; Sirri, L.; Marzola, E.; Roncuzzi, R.; Abbate-Daga, G.; Fava, G.A.; Rafanelli, C. An innovative approach to the assessment of mood disturbances in patients with acute coronary syndrome. CNS SPECTRUMS. [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.; Brugnera, A.; Adorni, R.; Tasca, G.A.; Compare, A.; Viganò, A.; Fattirolli, F.; Giannattasio, C.; D'Addario, M.; Steca, P. The role of sense of coherence in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms among patients at the first acute coronary event: A three-year longitudinal study. J PSYCHOSOM RES, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Chair, S.Y.; Zhang, C.; Bao, A. Depressive and anxiety symptoms and illness perception among patients with acute coronary syndrome. J ADV NURS, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.Y.; Li, Y.M.; Su, J.K.; Wang, Y.F.; Su, J.; Yang, Q.H. Effects of posttraumatic growth on psychosocial adjustment in young and middle-aged patients with acute myocardial infarction: The mediating role of rumination. HEART LUNG. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J TRAUMA STRESS. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. TARGET ARTICLE: \"Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence\". PSYCHOL INQ. [CrossRef]

- Norekvål, T.M.; Moons, P.; Hanestad, B.R.; Nordrehaug, J.E.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Fridlund, B. The other side of the coin: perceived positive effects of illness in women following acute myocardial infarction. EUR J CARDIOVASC NUR. [CrossRef]

- Affleck, G.; Tennen, H.; Croog, S.; Levine, S. Causal attribution, perceived benefits, and morbidity after a heart attack: an 8-year study. J CONSULT CLIN PSYCH. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Park, C.L.; Laflash, S. Perceived posttraumatic growth in cardiac patients: A systematic scoping review. J TRAUMA STRESS. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Taku, K.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth: Theory, Research, and Applications; 2018.

- Öcalan, S.; Üzar-Özçetin, Y.S. "I am in a Fight with My Brain": A Qualitative Study on Cancer-Related Ruminations of Individuals with Cancer. SEMIN ONCOL NURS, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.; Hevey, D.; Cogley, C.; O'Keeffe, F. A meta-analysis of the association between event-related rumination and posttraumatic growth: The Event-Related Rumination Inventory and the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. J TRAUMA STRESS, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ródenas-Perea, G.; Velasco-Barbancho, E.; Perona-Garcelán, S.; Rodríguez-Testal, J.F.; Senín-Calderón, C.; Crespo-Facorro, B.; Ruiz-Veguilla, M. Childhood and adolescent trauma and dissociation: The mediating role of rumination, intrusive thoughts and negative affect. SCAND J PSYCHOL. [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; Roth, T.; Cheng, P.; Ong, J.C.; Rosenbaum, E.; Drake, C.L. Mindfulness and nocturnal rumination are independently associated with symptoms of insomnia and depression during pregnancy. SLEEP HEALTH. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Xie, P.; Deng, H.; Qiu, L.; Liu, W.; Huang, D.; Xia, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X. Rumination and Depression in Chinese Adolescents With Mood Disorders: The Mediating Role of Resilience. J CLIN PSYCHIAT. [CrossRef]

- Trick, L.; Watkins, E.R.; Henley, W.; Gandhi, M.M.; Dickens, C. Perseverative negative thinking predicts depression in people with acute coronary syndrome. GEN HOSP PSYCHIAT. [CrossRef]

- Emery, L.; Sorrell, A.; Miles, C. Age Differences in Negative, but Not Positive, Rumination. J GERONTOL B-PSYCHOL. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Miyamoto, Y. Cultural Differences in Rumination and Psychological Correlates: The Role of Attribution. PERS SOC PSYCHOL B, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaizzi, P. Psychological research as a phenomenologist views it//Valle R, King M. Existential Phenomenological Alternatives for Psychology, 5: England: Oxford University Press, 1978, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Meli, L.; Birk, J.; Edmondson, D.; Bonanno, G.A. Trajectories of posttraumatic stress in patients with confirmed and rule-out acute coronary syndrome. GEN HOSP PSYCHIAT. [CrossRef]

- Meli, L.; Alcántara, C.; Sumner, J.A.; Swan, B.; Chang, B.P.; Edmondson, D. Enduring somatic threat perceptions and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in survivors of cardiac events. J HEALTH PSYCHOL, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.; Liu, A.K.; Qiu, W.Y.; Su, J.; Zhou, X.Y.; Gong, N.; Yang, Q.H. 'I'm still young… it doesn't matter' - A qualitative study on the neglect of prodromal myocardial infarction symptoms among young- and middle-aged adults. J ADV NURS. [CrossRef]

- Thanavaro, J.L.; Moore, S.M.; Anthony, M.K.; Narsavage, G.; Delicath, T. Predictors of poor coronary heart disease knowledge level in women without prior coronary heart disease. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. [CrossRef]

- Weibel, L.; Massarotto, P.; Hediger, H.; Mahrer-Imhof, R. Early education and counselling of patients with acute coronary syndrome. A pilot study for a randomized controlled trial. EUR J CARDIOVASC NUR. [CrossRef]

- Platte, S.; Wiesmann, U.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Kehl, D. Coping and rumination as predictors of posttraumatic growth and depreciation. CHIN J TRAUMATOL. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Guo, L.; He, Y.; Ma, K. Research progress on rumination in post-stroke patients. J NURS SCI. [CrossRef]

- Hammer, C.; Podlog, L.; Wadey, R.; Galli, N.; Forber-Pratt, A.J.; Newton, M. Cognitive processing following acquired disability for para sport athletes: a serial mediation model. DISABIL REHABIL, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, T.; Han, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, A. The relationship among resilience, rumination and posttraumatic growth in hemodialysis patients in North China. PSYCHOL HEALTH MED. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lopez, A.; De Raedt, R.; van Put, J.; Koster, E. A novel process-based approach to improve resilience: Effects of computerized mouse-based (gaze)contingent attention training (MCAT) on reappraisal and rumination. BEHAV RES THER. [CrossRef]

- Darsin, S.S.; Ahmad, A.; Rahmat, N.; Hmwe, N. Nurse-led intervention on knowledge, attitude and beliefs towards acute coronary syndrome. NURS CRIT CARE. [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Chen, S.H.; Li, X.T.; Huang, J.; Mei, R.R.; Qiu, T.Y.; Li, Y.M.; Zhang, H.L.; Chen, Q.N.; Xie, C.Y.; et al. Effects of Disease-Related Knowledge on Illness Perception and Psychological Status of Patients With COVID-19 in Hunan, China. DISASTER MED PUBLIC, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic characteristics.

| Participants |

Gender |

Age |

Degree of education |

Occupation situation |

Occupation刘type |

Medical form |

Economic pressures |

| N1 |

Female |

57 |

Junior middle school |

Employed |

Physical labour

|

Medical insurance |

Relatively large |

| N2 |

Male |

40 |

Senior middle school |

Employed |

Non-physical labour

|

Medical insurance |

A little bit large |

| N3 |

Male |

35 |

Junior college |

Employed |

Non-physical labour

|

Self-paying |

Commonly large |

| N4 |

Male |

46 |

Senior middle school |

Employed |

Physical labour

|

Medical insurance |

A little bit large |

| N5 |

Male |

43 |

Undergraduate college |

Employed |

Non-physical labour

|

Medical insurance |

Commonly large |

| N6 |

Male |

58 |

Senior middle school |

Employed |

Non-physical labour

|

Medical insurance |

No |

| N7 |

Male |

42 |

Technical secondary school |

Employed |

Non-physical labour

|

Medical insurance |

No |

| N8 |

Male |

51 |

Junior middle school |

Employed |

Physical labour

|

Medical insurance |

A little bit large |

| N9 |

Male |

59 |

Junior middle school |

Employed |

Non-physical labour

|

Medical insurance |

No |

| N10 |

Male |

37 |

Doctor degree |

Employed |

Non-physical labour

|

Self-paying |

No |

| N11 |

Male |

47 |

Master degree |

Employed |

Non-physical labour

|

Self-paying |

Extremely large |

| N12 |

Male |

57 |

Primary school |

Employed |

Physical labour

|

Medical insurance |

A little bit large |

| N13 |

Male |

50 |

Junior middle school |

Employed |

Non-physical labour

|

Self-paying |

Extremely large |

| N14 |

Male |

42 |

Junior middle school |

Unemployed |

Physical labour

|

Medical insurance |

Commonly large |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).