1. Introduction

Verbal encouragement (VE) and the use of music have been extensively studied for their potential to improve physical performance through a variety of mechanisms [

1,

2]. With regard to VE, one possible mechanism underlying its effectiveness is the

startle mechanism, a defensive reflex located in the brainstem that is activated in the presence of intense acoustic stimuli such as VE [

3]. This reflex is thought to enhance neural drive leading to increased force through several mechanisms: increasing motor unit recruitment, intensifying motor unit firing frequency, suppressing supraspinal inhibition, and regulating psychomotor arousal [

4,

5,

6]. In addition, VE was found to facilitate optimal mind-body alignment and help overcome challenges [

7]. In this context, Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy plays a key role, highlighting how confidence in one’s abilities is crucial for optimal performance [

8].

VE is effective in improving athletic performance across a wide range of disciplines, both on land [

9] and in water [

10], showing improvements not only in applied strength and endurance during dynamic activities such as soccer, tennis, cycling, running, and swimming [

2,

7,

10,

11] but also in the effectiveness of isometric and concentric muscle contractions in a variety of experimental contexts [

4,

12,

13]. This approach has led to significant increases not only in motor performance but also in physiological outcomes, including increases in heart rate and maximal oxygen consumption [

14,

15].

However, recent studies suggest that in experienced athletes the effectiveness of VE may be limited or even counterproductive by interfering with attentional focus strategies. For example, only modest improvements in upper body performance have been observed in elite rugby players [

16], just as there was no increase in isometric grip strength in senior male judokas [

17]. Similarly, comparing CrossFit sessions performed with and without VE in experienced athletes showed only modest improvements in strength performance when encouragement was present, whereas no significant difference was observed between the two conditions for high-intensity endurance exercises [

18].

Similarly, with regards to music, several studies have shown that it can be very useful for improving performance, especially if fast and loud [

19]. The main mechanism of this effect would be to divert concentration from feelings of fatigue during exercise [

20]. Furthermore, music can modify psychomotor arousal acting as both a stimulant and a sedative before and during physical activity, depending on the needs of the athlete and the context [

21]. Further research has shown that synchronizing the tempo of the music with the movement of the performer not only improves motor efficiency but can also optimize energy expenditure (kinetic and/or physiological efficiency) [

22,

23]. The efficacy of music in enhancing performance is so pronounced that its use has been banned in competitive sports settings.

Scientific research dealing with the effects of music on exercise performance has traditionally focused on examining a variety of physiological and perceptual parameters. These include task time, exercise endurance, lactate levels, maximal oxygen consumption, and the subjective experience of exertion [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

However, there is a lack of neurophysiological research using surface electromyography (EMG) that examines the precise effects of both VE and music on muscle excitation and the performer’s ability to resist muscular fatigue, suggesting that this is an under-explored area that could yield important insights. Moreover, a recent multi-level meta-analysis of 139 studies to quantify the effects of listening to music during exercise and sport found a paucity of studies that compared trained and untrained participants in a laboratory setting [

29]. Finally, there is a dramatic dearth of data concerning a direct comparison between the effects of VE and musical listening. To our knowledge, only one study [

30] has examined their effects on agility tests of young basketball players and found no significant differences in performance times.

Based on these premises, the aim of the present study is to investigate, in a group of subjects with different levels of physical fitness, muscle excitation and myoelectric manifestations of fatigue using EMG, as well as task duration, during an isometric exhaustion task, performed in three different conditions: standard conditions, when listening to self-selected motivational music and with VE support. In the absence of previous specific studies, muscle excitation and fatigue were considered as exploratory variables, with no pre-defined hypotheses. On the contrary, based on the pertinent literature, VE and musical conditions are expected to improve performance, particularly in untrained participants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethics Approval

This study used a single-blind randomized crossover methodological approach to analyze the effect of three different environmental interventions - i.e., standard conditions, music, and VE support - on performance in an isometric endurance task, comparing results between untrained and trained individuals. The intervals between each intervention, that is to say, the wash-out, were set at 10 days. The examinations and analyses were performed at the University Hospital “IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino”, Genoa, Italy. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy (protocol number 2024.37, April 12, 2024) and registered on the public website ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT06408155). Prior to the start of the experimental protocol, all participants were adequately informed of the need to undergo three different tests, although details of the specific methods were not given. They provided written, informed consent.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in the study, candidates had to be in good general health, with no medical conditions that would interfere with their ability to perform the test safely and effectively. In addition, to be considered trained, participants had to perform 150 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, in addition to muscle-strengthening activities, on at least two days per week, according to the guidelines of Piercy et al. [

31]. Those who did not meet this standard were considered to be unfit. Exclusion criteria included a history of surgery to the arm, shoulder, or nearby areas that might limit the ability to perform the test. The use of medications that affect muscle function or pain perception was also a reason for exclusion, so that the test results could not be influenced by external factors.

2.3. Study Sample

Based on the inclusion criteria, we assessed 30 physiatrists from the Policlinico San Martino Hospital, aged between 27 and 40 years. Out of these 30, two were excluded since they did not meet inclusion criteria. Finally, 28 physiatrists were recruited and divided into two groups according to their physical activity habits (

Table 1). Of these participants, 15 were untrained with a mean age of 29.57 ± 2.77 years (7 females). Another 13 were trained with a mean age of 32.92 ± 2.90 years (3 females).

2.4. Isometric Exhaustion Task

The protocol initially included a warm-up consisting of three sets of eight repetitions each, using a load equivalent to 50% of the individual’s one-repetition maximum (1RM). Next, the main exercise required participants to keep their arm flexed at a 90° angle while holding a dumbbell with a supine grip, loaded to 80% of their 1RM, on the dominant side of the body. During execution, the back and head were kept in contact with a vertical wall, with the feet shoulder width apart and firmly planted on the floor. The dumbbell was held with the dominant arm while the opposite arm remained in a neutral position close to the body (

Figure 1). It was mandatory to avoid any form of rocking, swaying, or movement that might facilitate holding the position, thus ensuring the integrity of the muscular endurance test. The test officially began when the dumbbell was handed to the subject, who was already in the correct position, and ended as soon as the angle of the arm varied by more than 5 degrees, both in flexion and in extension. The angle of the elbow joint was continuously monitored with an electronic goniometer (model TDS130B, Biopac System Inc, USA) placed directly on the joint.

VE was provided by the operator himself. Expressions chosen included: “Stay focused”, “Go for it, you’re stronger than you think”, “Keep going, you’re doing an amazing job”, “Don’t give up”, “You were born to win”, “Fatigue is temporary, satisfaction is eternal”, “Give your all”, “Believe in yourself”. These words were pronounced repeatedly to ensure that the subject was continuously encouraged throughout the test, avoiding periods of silence. The music was chosen according to the individual preferences of the participant. Both the VE and the music were presented at a level of between 75 and 80 decibels to ensure that they were clearly audible without being intrusive or damaging to hearing. One week prior to the start of the study, each participant’s 1RM was estimated using the Boyd Epley multiple repetition method [

33]. In addition, participants were given detailed instructions on how to maintain their usual diet, ensure adequate hydration, avoid alcohol and caffeine intake in the three hours before the test, and abstain from physical activity in the 48 hours before the assessment.

2.5. EMG Signal Processing

Bipolar surface electrodes were placed on the dominant side of the participant’s body, targeting three different muscle groups: the biceps brachii (BB), brachioradialis (BR) and triceps brachii (TB). The skin areas where the electrodes were placed were cleaned with alcohol and shaved if necessary. Electrodes were placed in accordance with the natural longitudinal orientation of the underlying muscle fibers, as described by De Luca [

34]. The exact positions for electrode placement were determined according to the protocols established in the ‘Surface EMG for Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles’ (SENIAM) guidelines [

35]. The EMG signal was acquired using a wireless EMG device (Cometa Srl, Milan, Italy) with a first-order band-pass filter in the range 10-500 Hz and digitized at 2000 samples/s. The electrical signals produced by the muscles were processed according to specific guidelines. The signals were filtered at a specific range (20-450 Hz), then rectified, smoothed with a low-pass filter (5 Hz, 4th-order Butterworth), and finally normalized with respect to the peak activity obtained from the reference signal, thus transforming the entire signal into a relative scale where the reference peak value represents 100%.

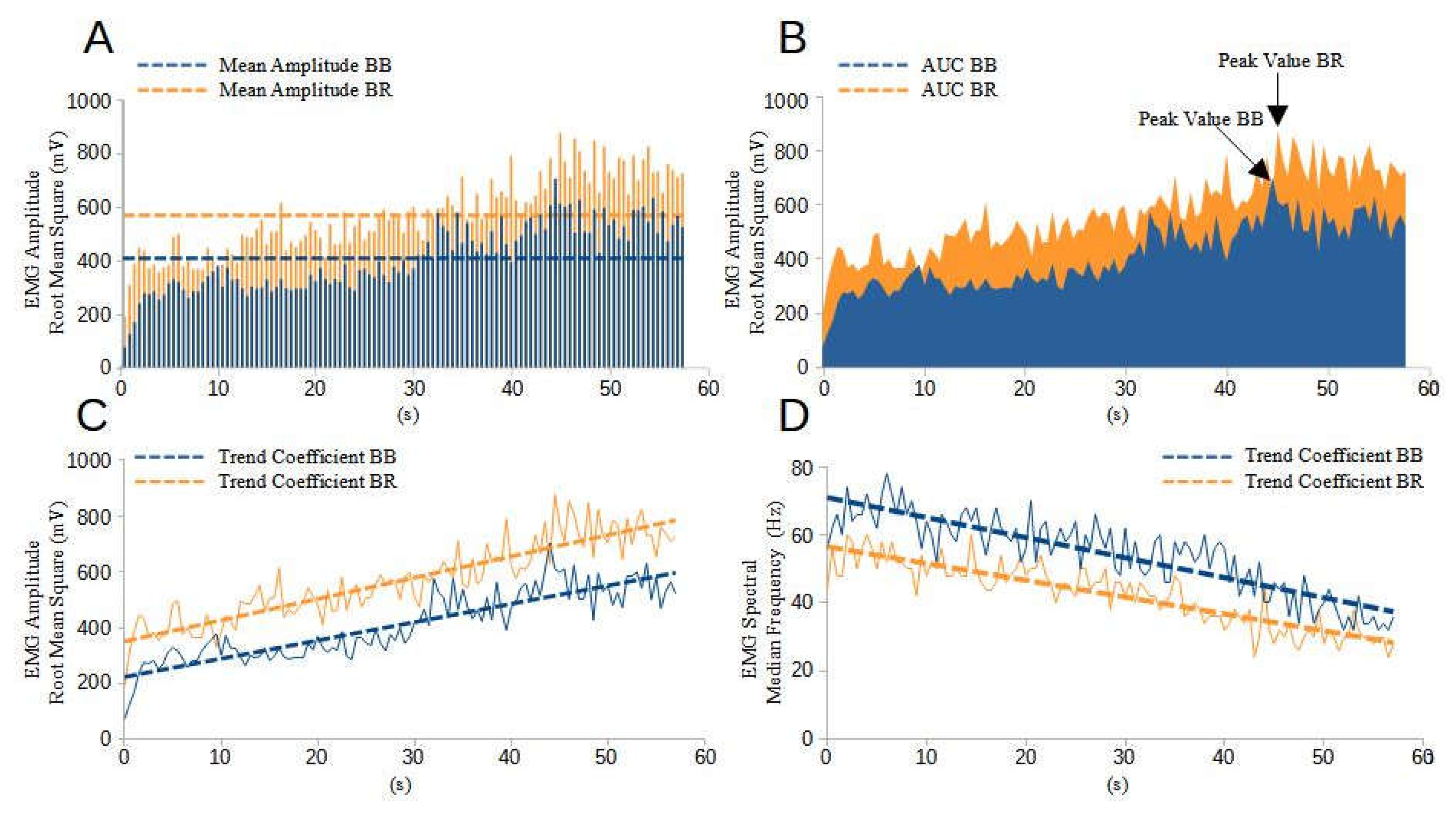

In order to assess the level of excitation of BB and TB muscles, the study measured the following EMG signal parameters: (i) the specific point during the test, expressed as a percentage, at which the highest level of muscle excitation occurs (peak value); (ii) the mean amplitude (mV); (iii) the trend coefficient of muscle excitation, expressed as a percentage of the time slope; and (iv) the Area Under the Curve (AUC) in units of %·s. The AUC represents the integral of the EMG signal, i.e., the total volume of electrical activity occurring during the task. In addition, (v) the co-contraction coefficient was calculated, defined as the ratio of activation of the TB muscle to activation of the BB muscle throughout the specified duration of the task.

To analyze the myoelectric manifestations of fatigue, an analysis of the EMG signal spectrum was carried out using a 0.5 second time window, starting exactly at the onset of activity. The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) was used to calculate the linear magnitude of the FFT for the selected data segments. The Median Frequency (MDF) was identified as the frequency corresponding to the 50th percentile of the cumulative energy distribution in the frequency spectrum, marking the division of the energy spectrum into two equivalent parts. The decrease in the signal power spectrum towards lower frequencies indicates a reduction in the conduction velocity in the muscle fibers. This phenomenon can be attributed to changes in the intracellular pH, which tends to become more acidic due to the increased concentration of H+ ions resulting from the hydrolysis of ATP to ADP and the accumulation of lactic acid during the performance of the task [

36]. The entire analysis process, including FFT and MDF determination, was facilitated using open-source Python software provided by Anaconda Inc. The resulting analysis produced a graph showing the values of MDF over time. To evaluate the temporal evolution of MDF, a linear fit of the data set was performed, and the slope (temporal slope of MDF) was derived. These slopes were, then, normalized to the value of the regression line at the start time of the first activation interval, analyzed, and expressed as percentages. A gradual decrease in MDF during exercise indicates the presence of muscle fatigue. In summary, in addition to measuring the task duration, four EMG outcome variables were calculated to analyze muscle activation, one variable for co-contraction, and one variable to quantify the myoelectric manifestations of fatigue.

Figure 2 provides useful visual information on outcome variables through an EMG representation of an untrained participant under VE conditions.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Prior to any statistical analysis, the dataset underwent a preliminary visual inspection to identify any potential outliers and ensure the integrity and accuracy of the subsequent analyses. Descriptive statistics were then performed, presenting the collected data in terms of means and standard deviations to provide a clear, concise overview of the characteristics of the dataset. Following this initial assessment, we tested the assumptions necessary for conducting a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), namely the normal distribution of the continuous dependent variables and the assumption of sphericity. This was to ensure the validity of our results. The two-way ANOVA was then used to test for the presence of statistically significant differences in performance scores across the three experimental conditions (Standard, Music, VE), the training status, and their interaction, thereby testing the null hypothesis of no variance in mean scores across conditions and the training status. Only interactions effects were hereby reported, being the findings of greater interest for the study.

As the two-way ANOVA indicated significant differences across the groups, subsequent post-hoc analyses were performed on the estimated marginal means. Also, for each pairwise comparison between conditions (Standard vs. Music, Standard vs. VE, and VE vs. Music), we calculated the Effect Size using Cohen’s d. This statistical measure provides a standardised magnitude of the difference between two group means relative to their combined standard deviation, thus providing a quantifiable measure of the significance of the effect. Commonly accepted thresholds for interpreting Cohen’s d indicate that a value of 0.20 is considered a small ES, 0.50 indicates a medium ES, and 0.80 signifies a large ES [

37]. All statistical procedures were performed using the open-source software R (R version 4.2.3, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

3. Results

3.1. Task Duration

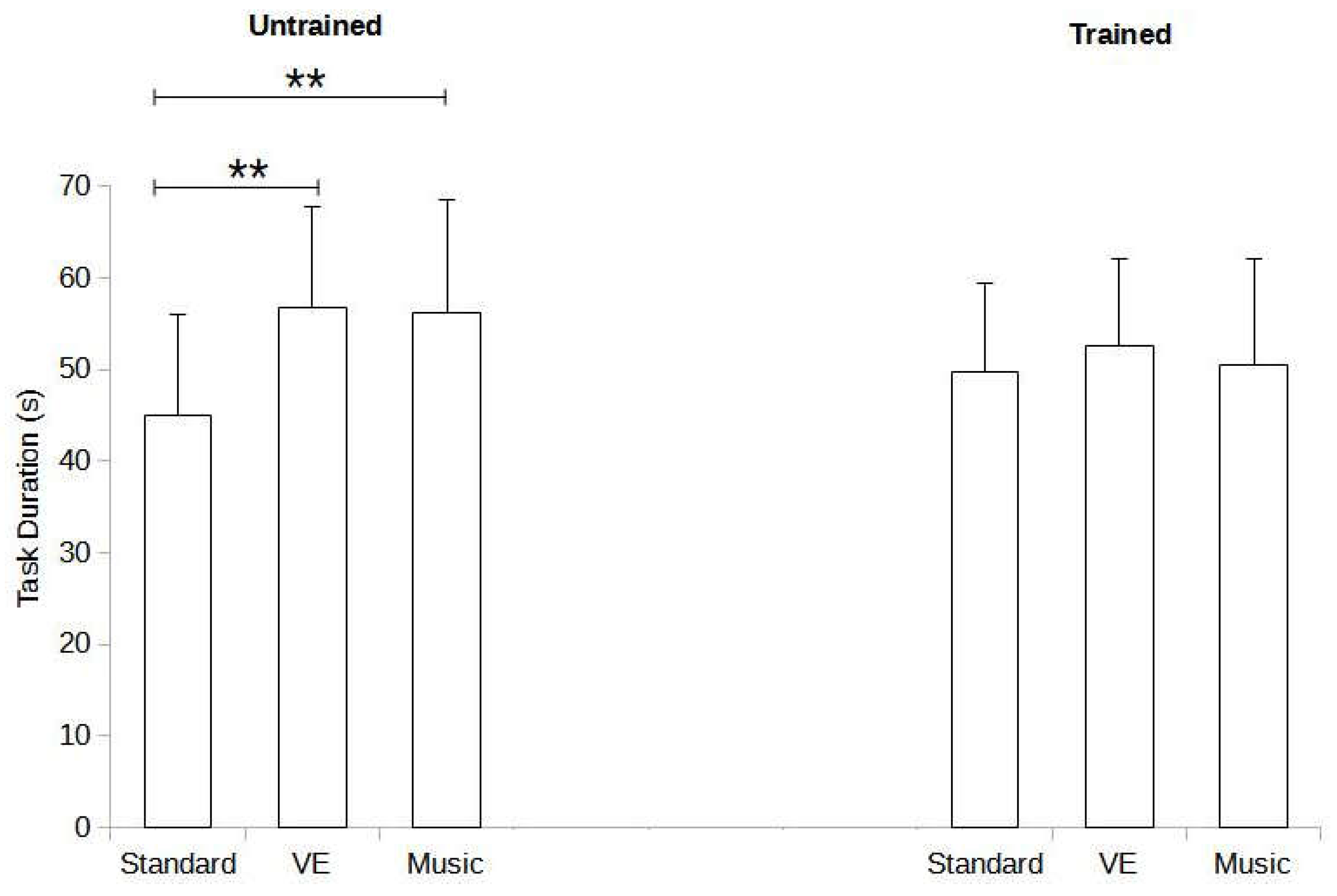

Significant effects were identified for the interactions between training status and the experimental condition (F = 3.693, p = 0.029). Post-hoc analysis for the untrained group revealed significant differences between standard and music conditions (mean difference [MD] = -15.26%, p < 0.003, Cohen’s d = -1.396) as well as between standard and VE conditions (MD = -15.85%, p < 0.002, Cohen’s d = -1.450). However, no significant differences were found between music and VE conditions (MD = -0.59%, p = 1.000, Cohen’s d = 0.054). In contrast, the trained group showed no significant differences in the post-hoc analysis (standard vs. music: MD = -0.81%, p = 1.000, Cohen’s d = 0.074; standard vs. VE: MD = -2.83%, p = 0.986, Cohen’s d = 0.259; music vs. VE: MD = -2.02%, p = 0.997, Cohen’s d = 0.185).

Figure 3 illustrates task duration in relation to training status and experimental condition.

3.1. Muscle Excitation

3.1.1. Mean Amplitude

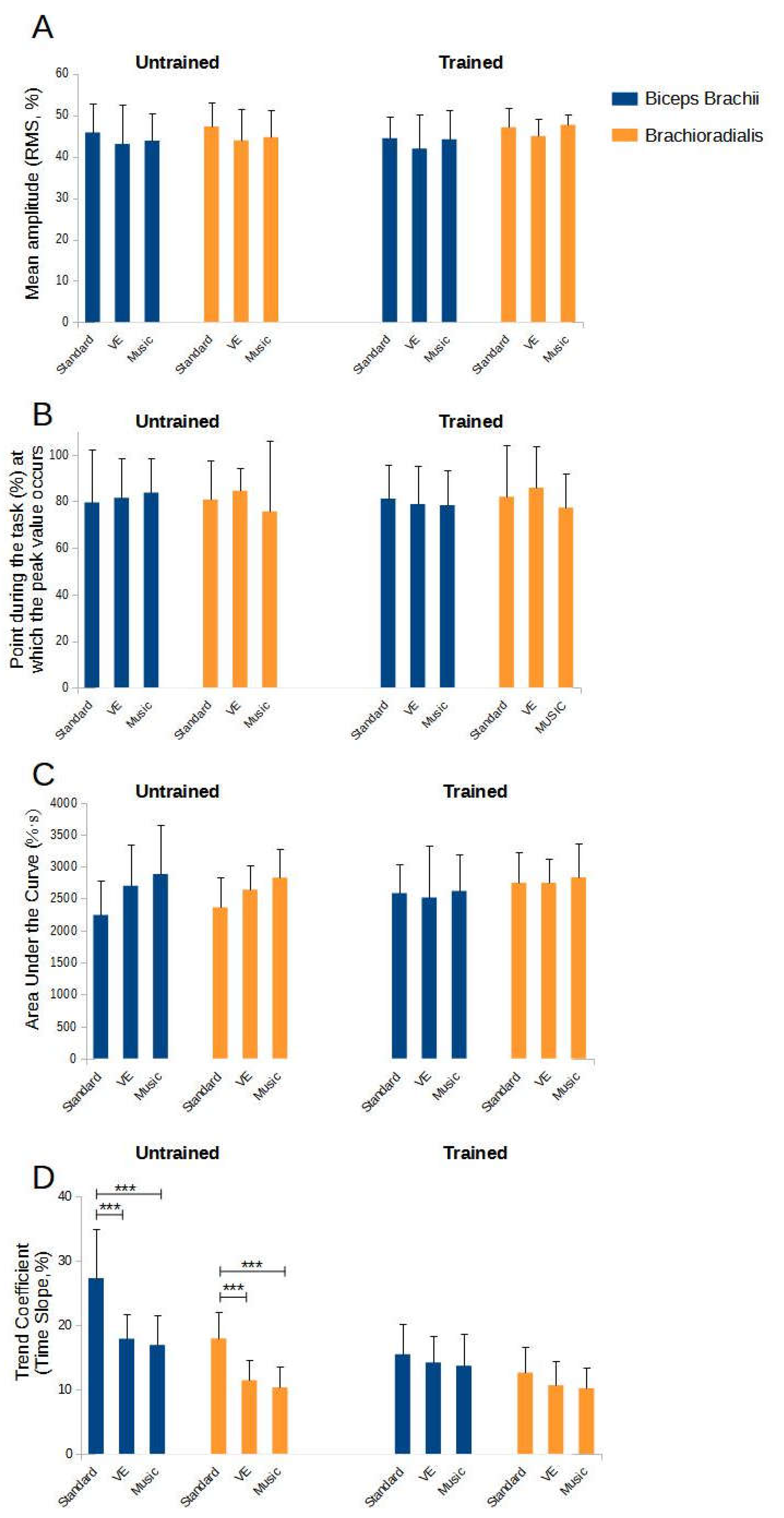

For the BB muscle, no significant effects were observed for the interactions between training status and the experimental condition (F = 0.111, p = 0.895). Similarly, for the BR muscle, no significant differences were found (F = 0.111, p = 0.895).

Figure 4A depicts the mean amplitude values relative to training status and experimental condition.

3.1.2. Peak Value

No significant effects were found for the interactions between training status and the experimental condition for the BB muscle (F = 0.297, p = 0.744) or the BR muscle (F = 0.001, p = 0.999).

Figure 4B depicts the peak value in relation to training status and experimental condition.

3.1.3. Area under the Curve

The AUC analysis revealed no significant effects for the interactions between training status and the experimental condition for the BB muscle (F = 1.826, p = 0.168) or the BR muscle (F = 1.370, p = 0.259).

Figure 4C shows the AUC values relative to training status and experimental condition.

3.1.4. Time Slope of the Trend Coefficient

A significant effect was detected for the BB muscle for the interactions between training status and the experimental condition (F = 6.060, p = 0.004). Post-hoc analysis for the untrained group showed significant differences between standard and music conditions (MD = 10.39%, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.009) and standard and VE conditions (MD = 9.40%, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.818), but not between music and VE conditions (MD = -0.99%, p = 0.995, Cohen’s d = 0.191). Conversely, the trained group showed no significant differences (standard vs. music: MD = 1.81%, p = 0.947, Cohen’s d = 0.350; standard vs. VE: MD = 1.29%, p = 0.988, Cohen’s d = 0.249; music vs. VE: MD = -0.56%, p = 1.000, Cohen’s d = 0.102).

For the BR muscle, significant effects were observed for the interactions between training status and the experimental condition (F = 4.340, p = 0.016). Post-hoc analysis for the untrained group revealed significant differences between standard and music conditions (MD = 7.61%, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.135) and standard and VE conditions (MD = 6.51%, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.826), but not between music and VE conditions (MD = -1.10%, p = 0.958, Cohen’s d = 0.309). The trained group showed no significant differences (standard vs. music: MD = 2.45%, p = 0.501, Cohen’s d = 0.688; standard vs. VE: MD = 1.99%, p = 0.715, Cohen’s d = 0.557; music vs. VE: MD = -0.47%, p = 0.999, Cohen’s d = 0.132).

Figure 4D depicts the values of the time slope of the trend coefficient in relation to the training state and the experimental condition.

3.1.5. Co-Contraction Coefficient

No significant effects were found for the co-contraction coefficient concerning the interactions between training status and the experimental condition (F = 0.030, p = 0.970).

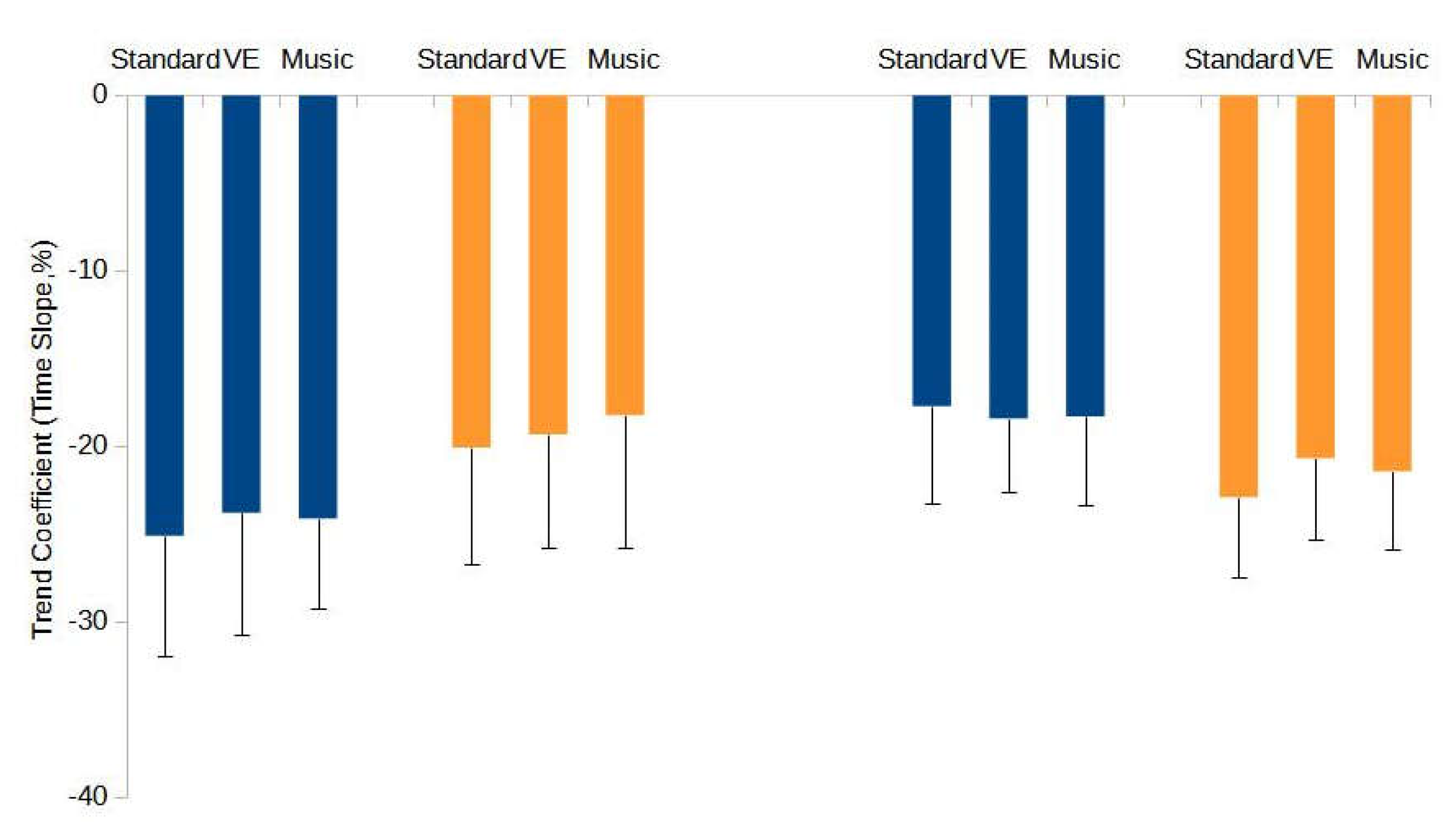

3.1.6. Myoelectric Manifestations of Muscle Fatigue

For the BB muscle, no significant effects were found for the interactions between training status and the experimental condition (F = 0.239, p = 0.788). Similarly, no significant effects were found for the BR muscle (F = 0.190, p = 0.828).

Figure 5 provides a visual representation of the myoelectric manifestations of muscle fatigue values relative to training status and experimental condition.

4. Discussion

This single-blind randomized crossover study investigated the effect of VE and music on task duration, muscle excitation and myoelectric manifestations of muscle fatigue assessed using EMG in individuals with different degrees of fitness, during an isometric task to exhaustion.

4.1. Task Duration

Exposure to either VE or self-selected music significantly increased task duration for the untrained population, indicating increased physical endurance. Specifically, the mean task duration without external stimuli was 45 seconds. This duration increased by 12 seconds when the task was performed with VE and by 11 seconds when the task was performed with music.

This result is in line with many previous studies in different sports and experimental settings. For example, there were time improvements of 10 seconds in 1.5 mile runs [

24] and 22 s seconds in 10 km cycling trials with musical accompaniment [

25]. Similarly, the use of VE resulted in time significant reductions of 1 second in the 200 m freestyle swim [

10] and 5 seconds in sprint tests with repeated changes of direction [

38]. It is thought that the increase in self-esteem resulting from VE, together with music’s ability to distract from fatigue and increase motivation during physical activity, are the psychological underpinnings of these benefits [

7,

20].

No significant differences were found between the two motivational feedback conditions. This result is due to the fact that almost half of the untrained participants showed greater improvements in task duration with music (7 out of 15), while the others found VE exposure more beneficial. This trend is also found in the only study that compared the effects of VE and music on repeated sprinting with change of direction in young basketball players [

30]. In particular, the authors found no significant changes in total time (sum of 10 sprints) and peak time (fastest sprint time) between the two experimental conditions. Furthermore, the authors discuss these results by highlighting how the uniqueness of everyone is clearly manifested in their preferences for receiving external feedback, highlighting that personal choice prevails over the hypothetical superiority of one condition over another.

In the analysis of trained subjects, the study found minimal and statistically insignificant variations in task duration (+ 3 seconds for VE and +1 second for music compared to the standard condition), indicating the possible presence of a ceiling effect on motivation. We suggest that trained subjects may have already reached a plateau of maximum motivation, making them less receptive or susceptible to additional external motivational stimuli. These results are also consistent with existing evidence in the literature suggesting that individuals with prior training experience may have developed advanced cognitive skills [

18,

29]. Such skills would reduce the need to rely on external stimuli to improve performance. This implies that through experience and constant practice, these individuals have honed effective mental methods and strategies capable of improving training effectiveness independently of external motivational or distracting factors [

17].

Also, in the study by Engel et al. [

18], experienced adult CrossFit athletes were tested in a randomized order under two conditions, with and without VE. It was found that there were only small differences in the maximum weight lifted in the squat, with an increase of 2 kg in the presence of VE. In addition, no significant differences were observed between the two conditions in high-intensity functional training task measured as the maximum number of repetitions possible. This dynamic is also supported by the study of senior judo athletes, who showed slightly lower maximal isometric grip strength in the presence of VE, suggesting a possible preference on the part of these athletes for a quieter, more focused environment that promotes concentration rather than the addition of external distractions [

17].

In a parallel line of research, Argus et al. [

16] observed modest improvements in mean peak power and mean peak velocity during bench throw exercise, with increases of 1.8% and 1.3% respectively when rugby players received VE immediately after each attempt. The authors suggest that these limited improvements may be due to the ability of elite athletes to recruit a greater percentage of muscle fibers than untrained individuals. Therefore, for less experienced or untrained individuals, verbal feedback and motivational strategies may have a greater impact on muscle activation, leading to more significant improvements in performance.

Similarly, research conducted by Bigliassi et al. [

39] explored the impact of listening to music on the performance and psychophysical responses of trained cyclists during a 5 km time trial. They found that the effect of music, whether listened to before or during exercise, did not lead to significant changes in performance compared to a control condition without music.

4.2. EMG Assessment (Muscle Excitation and Myoelectric Manifestations of Fatigue)

In trained subjects, the phenomenon whereby the level of muscular excitation and myoelectric manifestations of fatigue remain stable, regardless of external stimuli, is due to the constancy of their task duration. In other words, the absence of significant variations in performance time of these subjects was reflected in uniform EMG measurements across different experimental conditions. In contrast, a significant variation in task duration in response to stimuli was observed in untrained subjects. However, despite these variations, the analysis carried out showed no changes across the three conditions of the mean amplitude, peak value and AUC indicating a similar level of neuromotor engagement, leading to a similar level of myoelectric manifestations of fatigue. Interestingly, when feedback was provided, either through VE or the use of music, there was a significant reduction in the time slope of the trend coefficient compared to the control environment without feedback for both muscles tested (time slope for BB -9% for VE and -10% for music, and time slope for BR -7% for VE and -8% for music).

The time slope of the trend coefficient measures the progressive recruitment of motor units that occurred during the task according to Henneman’s principle [

40]. This principle states that during submaximal tasks that are prolonged over time, the smaller motor units, which are less susceptible to rapid fatigue, are activated first, with progressive involvement of the larger motor units depending on the intensity and duration of the task. A greater time slope of the coefficient indicates more rapid recruitment of the larger motor units than a smaller time slope. Therefore, the observed phenomenon of a more gradual recruitment of the larger and more easily fatigued motor units in the VE and musical conditions could explain the better temporal performance. In other words, the delayed activation of these motor units, which are less energy efficient but necessary to sustain intense effort, probably allowed the subjects to maintain an optimal level of effort for a longer period of time, resulting in improved performance and similar degrees of myoelectric fatigue compared to shorter tasks.

This phenomenon is in line with what is known about the psychological and neuromuscular effects of music. Music not only helps reduce the perception of fatigue through changes in attentional focus [

20], but also promotes an improvement in the efficiency of muscle contractions [

41]. The relationship between attention and muscular efficiency is described by the constrained action hypothesis [

42]. It suggests that focusing attention on external elements, such as emotions or memories evoked by music, rather than on internal muscular sensations, may facilitate the use of more automatic control mechanisms. This approach could contribute to greater fluidity and stability of muscle contraction, promoting more gradual and efficient recruitment of motor units without the interruption of conscious monitoring of actions [

43]. Conversely, focusing on one’s muscular sensations (internal attention) during a task could lead to a more conscious and deliberate control of the action, which may interfere with the efficiency of the contraction, resulting in a less stable and more fragmented execution [

42,

44].

Contrary to expectations based on the supposed role played by startle mechanism [

3], VE did not induce significant changes in participants’ muscle excitation, a result that seems to contradict evidence from previous studies. For example, the study by Belkhiria et al. [

4] analysed the effects of VE on maximal isometric force and EMG parameters in twenty-three participants and found a 21% increase in force production and a 12% increase in muscle excitation with VE compared to the condition without encouragement. Also, Binboğa et al. [

13] found a 10% increase in muscle excitation in the sural triceps muscle group during a maximal plantar flexion contraction in subjects with low conscientiousness, although the effect on motor output was not analysed.

This discrepancy raises questions about the universal applicability of the startle mechanism, suggesting the presence of additional variables or specific contexts in which the effectiveness of VE may vary significantly. Furthermore, most studies of VE in controlled contexts focus on maximal contractions, leaving little room to explore the management of motor recruitment under more variable and less extreme conditions.

5. Conclusions

The study investigated the effects of VE and music on physical performance during an isometric exhaustion task and found an increase in task duration in untrained subjects compared to the condition without additional stimuli. Further, the use of external stimuli in these participants led to a decrease in the time slope of the trend coefficient in the muscles studied (BB and BR), suggesting a more homogeneous and efficient muscle recruitment process. This dynamic may have enabled the subjects to maintain sustained effort for longer periods of time, resulting in increased temporal performance and myoelectric responses to muscle fatigue comparable to that recorded during exercise of shorter duration (without external stimuli). Comparison of the effects of music and VE showed no significant differences, suggesting that preference for one or the other motivational tool is a matter of personal taste rather than superiority in terms of effectiveness. On the contrary, in the trained subjects, no significant differences were found between the experimental conditions, either in the duration of the task or in the variables related to muscle excitation and myoelectric manifestations of fatigue (EMG assessment), suggesting the presence of a ceiling effect of motivation. These results emphasize the crucial role of external stimuli in improving motor task performance in untrained subjects and suggest a possible application in physical rehabilitation programs to increase patient involvement and maximize the benefits of therapeutic exercise, especially for individuals with low motivation or a tendency to premature fatigue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C.,L.P. and N.B.; methodology, F.C. and L:P:; software, L.M..; validation, L.P., C.T. and L.Mo.; formal analysis, N.B. and L.M.; investigation, F.C., L.P., C.S., E.F.; resources, F.C., L.P., C.S., E.F; data curation, N.B., C.B..; writing—original draft preparation, L.P., P.R., C.B., N.L.B., H.İ.C., and C.T.; writing—review and editing, L.P., P.R., C.B., C.T., N.L.B., and E.F.; visualization, L.P.; supervision, L.P.,C.T., P.R. and C.B.; project administration, L.P.; funding acquisition, C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy (protocol number 2024.37) for studies involving humans and registered on the public website ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT06408155).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Midgley, A.W.; Marchant, D.C.; Levy, A.R. A call to action towards an evidence-based approach to using verbal encouragement during maximal exercise testing. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2018, 38, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaba-Jakovljevic, D.; Popadic-Gacesa, J.; Grujic, N.; Barak, O.; Drapsin, M. Motivation and motoric tests in sports. Med. Pregl. 2007, 60, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, M. The neurobiology of startle. Prog. Neurobiol. 1999, 59, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkhiria, C.; De Marco, G.; Driss, T. Effects of verbal encouragement on force and electromyographic activations during exercise. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2018, 58, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giray, M.; Ulrich, R. Motor coactivation revealed by response force in divided and focused attention. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1993, 19, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNair, P.J.; Depledge, J.; Brettkelly, M.; Stanley, S.N. Verbal encouragement: effects on maximum effort voluntary muscle action. Br. J. Sports Med. 1996, 30, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydi, B.; Selmi, O.; Souissi, M.A.; Sahli, H.; Rekik, G.; Crowley-McHattan, Z.J. , et al. The Effects of Verbal Encouragement during a Soccer Dribbling Circuit on Physical and Psychophysiological Responses: An Exploratory Study in a Physical Education Setting. Children 2022, 9, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campenella, B.; Mattacola, C.G.; Kimura, I.F. Effect of visual feedback and verbal encouragement on concentric quadriceps and hamstrings peak torque of males and females. Int. J. Sports Sci. 2000, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puce, L.; Trompetto, C.; Currà, A.; Marinelli, L.; Mori, L.; Panascì, M. , et al. The Effect of Verbal Encouragement on Performance and Muscle Fatigue in Swimming. Medicina 2022, 58, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilit, B.; Arslan, E.; Akca, F.; Aras, D.; Soylu, Y.; Clemente, F.M. , et al. Effect of Coach Encouragement on the Psychophysiological and Performance Responses of Young Tennis Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendos, N.K.; Harriell, K.; Qazi, S.; Regis, R.C.; Alipio, T.C.; Signorile, J.F. Variations in Verbal Encouragement Modify Isokinetic Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binboğa, E.; Tok, S.; Catikkas, F.; Guven, S.; Dane, S. The effects of verbal encouragement and conscientiousness on maximal voluntary contraction of the triceps surae muscle in elite athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31, 982–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacholek, M.; Zemková, E. Effects of Verbal Encouragement and Performance Feedback on Physical Fitness in Young Adults. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreacci, J.L.; Lemura, L.M.; Cohen, S.L.; Urbansky, E.A.; Chelland, S.A.; Duvillard, S.P. von. The effects of frequency of encouragement on performance during maximal exercise testing. J. Sports Sci. 2002, 20, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argus, C.K.; Gill, N.D.; Keogh, J.W.; Hopkins, W.G. Acute Effects of Verbal Feedback on Upper-Body Performance in Elite Athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 3282–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obmiński, Z.; Mroczkowska, H. Verbal encouragement does not improve maximal isometric hand grip strength in male judokas. A short report. J. Combat Sports Martial Arts 2015, 6, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, F.A.; Faude, O.; Kölling, S.; Kellmann, M.; Donath, L. Verbal Encouragement and Between-Day Reliability During High-Intensity Functional Strength and Endurance Performance Testing. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyck, E. Musical Intensity Applied in the Sports and Exercise Domain: An Effective Strategy to Boost Performance? Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, J.C.; Karageorghis, C.I. Moderating Influence of Dominant Attentional Style and Exercise Intensity on Responses to Asynchronous Music. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 35, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juslin, P.N. From everyday emotions to aesthetic emotions: Towards a unified theory of musical emotions. Phys. Life Rev. 2013, 10, 235–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, P.C.; Karageorghis, C.I.; Saha, A.M.; D’Auria, S. Effects of synchronous music on treadmill running among elite triathletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2012, 15, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.J.; Myers, T.R.; Karageorghis, C.I. Effect of music-movement synchrony on exercise oxygen consumption. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2012, 52, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.C.; Baghurst, T.; Redus, B.S. Self-Selected Motivational Music on the Performance and Perceived Exertion of Runners. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 1656–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, G.; Wilson, D.; Eubank, M. Effects of Music on Work-Rate Distribution During a Cycling Time Trial. Int. J. Sports Med. 2004, 25, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, J.M.; Hall, J.; Arnold, R.; Karageorghis, C.I.; Hussein, A. Effects of music and music-video on core affect during exercise at the lactate threshold. Psychol. Music 2016, 44, 1471–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.B.T.; Karageorghis, C.I.; Romer, L.M.; Bishop, D.T. Psychophysiological Effects of Synchronous versus Asynchronous Music during Cycling. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakare, A.E.; Mehrotra, R.; Singh, A. Effect of music tempo on exercise performance and heart rate among young adults. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2017, 9, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Terry, P.C.; Karageorghis, C.I.; Curran, M.L.; Martin, O.V.; Parsons-Smith, R.L. Effects of music in exercise and sport: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 91–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammami, R.; Nebigh, A.; Selmi, M.A.; Rebai, H.; Versic, S.; Drid, P.; et al. Acute Effects of Verbal Encouragement and Listening to Preferred Music on Maximal Repeated Change-of-Direction Performance in Adolescent Elite Basketball Players—Preliminary Report. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A. , et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018, 320, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasco-Lafarga, C.; Ricart, B.; Cordellat, A.; Roldán, A.; Navarro-Roncal, C.; Monteagudo, P. High versus low motivating music on intermittent fitness and agility in young well-trained basketball players. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 20, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, B. Poundage chart in Boyd Epley Workout. Body Enterp. 1985, 86. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, C.J. The Use of Surface Electromyography in Biomechanics. J. Appl. Biomech. 1997, 13, 135–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2000, 10, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifrek, M.; Medved, V.; Tonković, S.; Ostojić, S. Surface EMG based muscle fatigue evaluation in biomechanics. Clin. Biomech. 2009, 24, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahli, H.; Haddad, M.; Jebabli, N.; Sahli, F.; Ouergui, I.; Ouerghi, N. , et al. The Effects of Verbal Encouragement and Compliments on Physical Performance and Psychophysiological Responses During the Repeated Change of Direction Sprint Test. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 698673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliassi, M.; Dantas, J.L.; Carneiro, J.G.; Smirmaul, B.P.C.; Altimari, L.R. Influence of music and its moments of application on performance and psychophysiological parameters during a 5km time trial. Rev. Andal. Med. Deporte 2012, 5, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneman, E.; Somjen, G.; Carpenter, D.O. Excitability and inhibitibility of motoneurons of different sizes. J. Neurophysiol. 1965, 28, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.R.; Hutchinson, J.C.; Winter, C.; Dalton, P.C.; Bolgla, L.A.; Paolone, V.J. Music alters heart rate and psychological responses but not muscle activation during light-intensity isometric exercise. Sports Med. Health Sci. 2024, S2666337624000088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, G. Attentional focus and motor learning: a review of 15 years. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 6, 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, J.; Wulf, G.; Töllner, T.; McNevin, N.; Mercer, J. EMG Activity as a Function of the Performer’s Focus of Attention. J. Mot. Behav. 2004, 36, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohse, K.R.; Sherwood, D.E.; Healy, A.F. How changing the focus of attention affects performance, kinematics, and electromyography in dart throwing. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2010, 29, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).