1. Introduction

The global crisis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has had a profound impact on human lives, causing numerous infections and deaths [

1]. The uncertainty surrounding the situation and the experience of quarantine have adversely affected people’s mental health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence rates of various mental health issues including depression, anxiety, stress, sleep problems, and overall psychological distress were observed to be higher in the general population. [

2,

3]. Resulting from the COVID-19 situation, individuals are required to develop coping skills to respond to the sudden changes such as isolation, infection anxiety, employment restrictions, telecommuting, reduced working hours, and economic impacts [

4].

While the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected mental health across genders, ages, and races, this study specifically targeted college students who undergo a crucial transition from adolescence to young adulthood, marked by newfound independence. During this phase, they cultivate diverse relationships, pursue academic goals, and reflect on their identities and career paths. However, this period also correlates with an increased prevalence of mental disorders such as emotional distress, anxiety, and substance use [

5]. Changes in educational and employment landscapes have exacerbated challenges related to identity formation, emotional turmoil, and financial strain [

6]. Consequently, stress, anxiety, depression, alcohol consumption, and drug use have escalated among college students during the pandemic, underscoring the urgent need for support and intervention [

6,

7,

8].

To address mental health challenges among college students, promoting positive factors like self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience is crucial. Positive psychotherapy, a method rooted in character strengths, emphasizes positive affect [

9]. Positive affect, which is a positive factor in personal development and achievement, encompasses inner joy, physical and mental well-being, satisfaction, life balance, and practical aspects that influence human thoughts, emotions, and behavior [

10]. Studies have suggested that higher positive affect is associated with reduced stress, anxiety, and depression, as well as a higher quality of life in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic [

11,

12]. Positive affect is linked to positive rumination, which involves looking at difficult situations in a favorable light and thinking positively about one’s own characteristics and current emotional states [

13]. Increased positive affect and positive rumination contribute to clearer emotional awareness, while employing positive affect as a coping strategy leads to decreased experience of negative affect in daily life events. [

13]. This suggests that the principles of positive psychotherapy can serve as effective coping strategies for improving mental health.

To foster resilience and well-being amidst the profound mental health challenges wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, there arises a pressing need for interventions grounded in positive psychotherapy. In particular, positive psychology-based music therapy is an intervention based on the principles of positive psychotherapy developed by Martin Seligman, aiming to improve an individual’s positive affect, such as strengths, gratitude, and hope, while fostering a deeper sense of meaning in life and the pursuit of overall happiness [

14]. In addition, positive psychology-based therapy recognizes the significance of social connections, where individuals can obtain intellectual and emotional satisfaction in their relationships with others as an essential element for a happy life along with personal growth [

15]. Recently, there has been a steady increase in research on positive psychology-based music therapy in various populations, such as infants, children, adolescents, patients, and the older adults [

16,

17,

18]. Positive psychology-based music therapy integrates techniques from music therapy with principles from positive psychotherapy. It focuses on key themes of positive psychology like positive emotions, gratitude, willpower, finding meaning in life, and envisioning a positive future [

19]. By incorporating activities such as singing, playing instruments, listening to music, and writing lyrics, this approach enables clients to comfortably and authentically engage in therapeutic experiences. While experiencing music provided in the music therapy environment, the client is invited to have psychological experiences and understand and analyze their reactions to stimuli (i.e., music or sound). Through this process, they can cognitively identify their problems, deal with related emotions, and develop new perspectives for applying and solving psychological problems.

Virtual music therapy emerges as a promising avenue for intervention, harnessing the therapeutic potential of music to cultivate positive emotions, enhance coping mechanisms, and facilitate psychological growth [

20]. Music, known for its ability to evoke a wide range of emotions and promote a sense of connection, serves as a potent medium for fostering positive affect and enhancing psychological well-being [

20]. Through guided exercises and interactive engagement, virtual music therapy interventions not only alleviate distress but also promote the cultivation of positive emotions and strengths [

21]. Furthermore, given the pandemic's constraints on face-to-face services and limited mental health personnel, addressing individual psychological difficulties consistently poses significant challenges. In this context, the digital realm affords unprecedented opportunities for remote delivery of music therapy interventions, enabling individuals to access therapeutic resources from the confines of their homes.

Recently, the effectiveness of virtual music therapy as a coping strategy for mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic has been reported. For example, clinical staff working with COVID-19 patients participated in a remote receptive music therapy intervention over a 5-week period and indicated a significant decrease in the intensity of tiredness, sadness, fear, and worry [

22]. A recent study which conducted a 12-day program of home-based music therapy in children with developmental delay reported a significant improvement in children’s sleep quality and a reduction of parental distress [

22]. However, existing studies on music therapy during the Covid-19 pandemic have certain limitations. These studies typically offered one-on-one personalized therapy sessions, limited experiences to passive listening to music, and primarily focused on clinical populations [

22,

23]. Consequently, there remains a gap in research regarding the impact of virtual music therapy on addressing the psychological challenges faced by healthy young adults during the pandemic. Furthermore, in the previous studies of music therapy, the main activity has been listening to specific music, which limited participants’ cognitive efforts to actively identify and overcome their situation or problem.

Therefore, this study endeavored to address this gap by developing a self-administered virtual music therapy program grounded in positive psychology principles. The aim of the present study was to investigate the program's effects on stress, anxiety, depression, and positive affect of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. By integrating the principles of positive psychology and music therapy into a digital platform, the study aimed to assess its effectiveness in providing collegiate participants with a comprehensive approach to mental health, empowering individuals to navigate the challenges of the pandemic with resilience and optimism.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

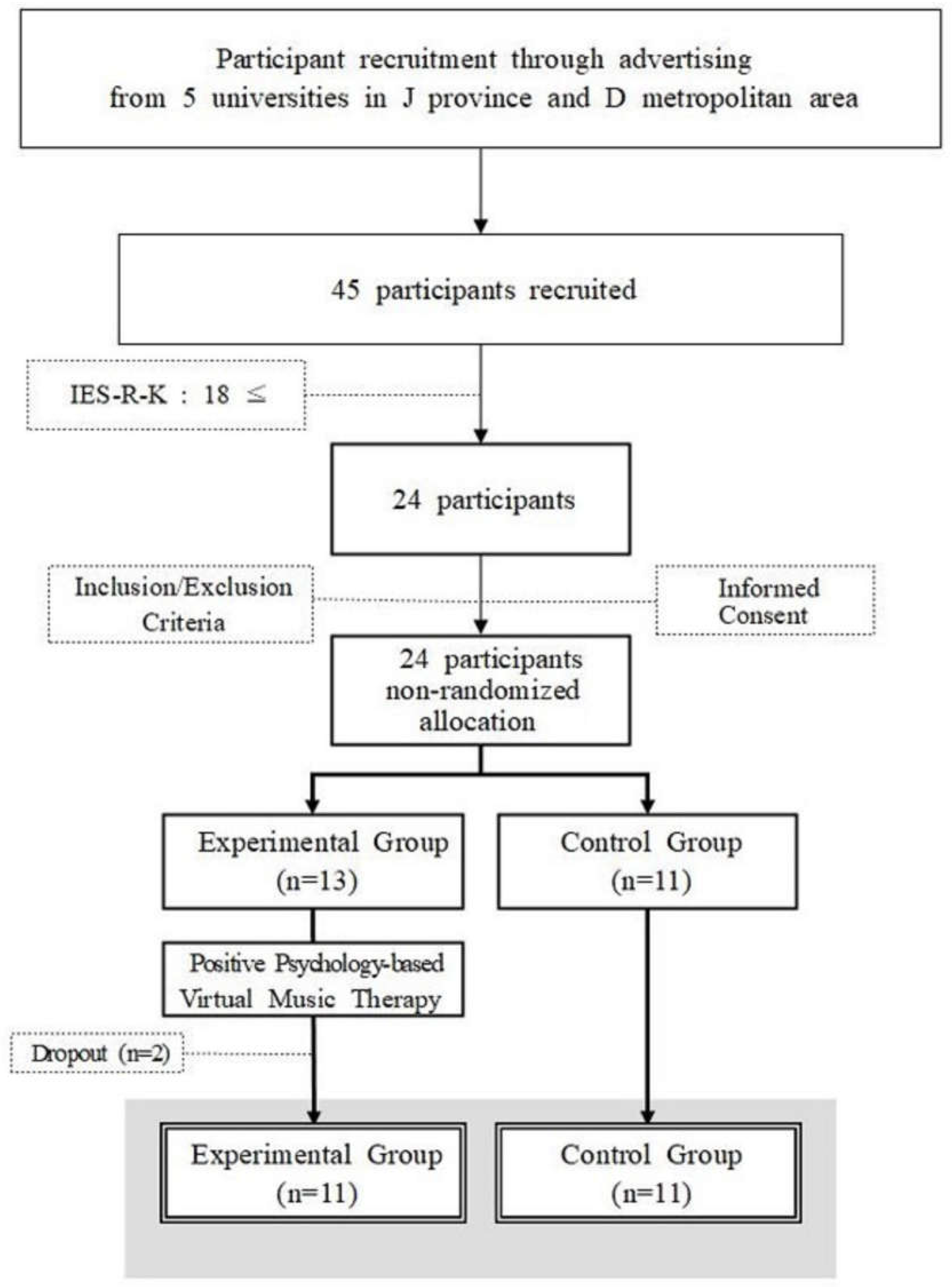

Participants were recruited from four universities located in J province and one university located in the D metropolitan area in South Korea. According to the inclusion criteria, 24 volunteers who scored 18 points or higher on the Korean Version of Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R-K), indicating partial post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), participated in the study (

Figure 1) [

24]. The 24 participants were non-randomly assigned to either the experimental group participating in the positive psychology-based virtual music therapy program or the control group receiving no treatment. Two participants dropped out of the experimental group during the study, resulting in a final count of 11 participants in both the experimental and control groups. The inclusion criteria encompassed college students aged 20 to 29 enrolled in a regular undergraduate program during the study. Applicants who had undergone psychiatric treatment in the past or were currently receiving it, or were undergoing psychological counseling, were excluded. All participants received prior explanation of the research, including its purpose, procedures, the positive psychology-based virtual music therapy program, and expected benefits, and provided written consent. Approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board for Ethics in Human Research at Wonkwang University (approval no. WKIRB-202102-HR-005). This study's clinical trial has been registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS) associated with the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (registration number: KCT0009532).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Impact of Event Scale-Revised Korean Version (IES-R-K)

The Korean Version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R-K) [

24], which was adapted from the original version, was employed as an inclusion criterion [

25,

26]. This scale consists of 22 items that are restructured into six items for intrusion (e.g., intrusive thoughts, nightmares), six for avoidance (e.g., avoidance of reminders of the traumatic event), five for hyperarousal (e.g., heightened startle response), and five for sleep disturbance and emotional numbing symptoms. This scale uses a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely high). The cutoff points for screening full PTSD and partial PTSD are 24/25 and 17/18, respectively. The overall Cronbach’s α for the items was .89.

2.2.2. 21-Item Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS 21)

To assess changes in depression, anxiety, and stress resulting from participation in the positive psychology-based virtual music therapy program, we used the 21-Item Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), which was adapted from the original 42-item version [

27,

28,

29]. The scale consists of three subscales: depression, anxiety, and stress, each with seven items. It utilizes a 4-point Likert scale (0 to 3), with subscale scores obtained by doubling the raw scores. For depression, scores of 0-9 were considered normal and 10-13, 14-20, 21-27, and ≥28 were considered mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe depression, respectively. For anxiety, scores of 0-7 were considered normal and 8-9, 10-14, 15-19, and ≥20 were considered mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe anxiety. For stress, scores of 0-14 were considered normal and 15-18, 19-25, 26-33, and ≥34 were considered mild, moderate, severe, and >extremely severe stress. The Cronbach's alpha for the entire scale was .926, and for the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales, the Cronbach's alpha values were .81, .84, and .85, respectively.

2.2.3. Korean Version of Positive Psychological Capital (K-PPC)

We evaluated changes in positive psychological resources among participants using the Korean Version of Positive Psychological Capital (K-PPC), adapted from Positive Psychological Capital (PsyCap) [

30,

31]. Consisting of 18 items and four sub-factors, the scale assesses an individual's positive psychological state, characterized by beliefs in their ability to pursue goals (hope), confidence in their skills (self-efficacy), capacity to rebound from setbacks (resilience), and optimistic outlook on future outcomes (optimism), based on a 5-point Likert scale. Overall Cronbach's α of the scale was .93, with the Cronbach's α of each sub-factor as follows: self-efficacy .879, optimism .822, hope .837, and resilience .723.

2.3. Procedure

Prior to the first session of the positive psychology-based virtual music therapy program, the purpose of the study was explained to the participants in both the experimental and control groups, and informed consent was obtained. Sociodemographic characteristics, IES-R-K, DASS 21, and K-PPC scores were obtained from both groups. The experimental group participants received 15 sessions' worth of video clips of the positive psychology-based virtual music therapy program along with accompanying worksheets at the outset of the research, which they could download onto their personal electronic devices. They were instructed to complete one session per weekday over a three-week period, granting them autonomy to engage in the program without constraints of time and space. The DASS 21 and K-PPC were reassessed in both groups immediately after the three-week program concluded, as well as at a three-week follow-up.

2.4. Intervention: Positive Psychology-Based Virtual Music Therapy

Based on the Positive Psychotherapy Clinical Manual and the items of the DASS 21 and K-PPC, we developed a virtual music therapy program incorporating elements of positive psychology such as positive affect, meaning of life, personal strengths, gratitude, hope, and happiness [

9,

14,

15,

16,

17]. The validity of the program was confirmed through consultations with a psychiatrist and two music therapists. The program duration was three weeks, with sessions held five times a week, totaling 15 sessions. Each session lasted for 20 minutes, and all sessions were delivered to participants in a pre-recorded video format. Throughout the program, participants were instructed to engage in tasks aligned with the session theme, such as writing down thoughts, emotions, relationships, and reflections, as directed by the therapist in the video.

The structure of each session was as follows: sessions 1-4 focused on the cognitive perspective of self-awareness, sessions 5-8 on the emotional perspective of self-awareness, and sessions 9-15 on exploring the meaning of life and relationships with others. In each session, consistent elements included the relaxation and presence phase to bring attention to the here and now through breathing and muscle relaxation, the practice and reflection phase to achieve session-specific goals, and finally, the stage of acceptance where the content recognized during the practice and reflection stages is accepted without judgment.

Music served three purposes in this program. First, music was used to facilitate the exploration of cognition, emotion, and relationships, enhancing overall experience. Second, it was used as a means for the participants to actively express and reflect on their experiences, fostering insight and self-awareness. Finally, music provided enjoyment, aiding in coping with anxiety or depression, and induced mood changes through aesthetic experiences [

9].

This program strategically incorporated musical elements including tempo, tonality, melody, musical texture, timbre, and orchestration. Throughout the sessions, a piano melody in a major key with a BPM of 65 and the sound of ocean waves were consistently provided to the participants as part of the theme-related working process. The therapist also provided piano and guitar accompaniments with a steady beat and root note to create a safe and predictable musical environment. In addition, depending on the theme of each session, third and fourth chords were added during music appreciation to provide a richer musical experience. In addition to appreciating music, the program included activities such as music autobiography, creating new lyrics, analyzing song lyrics, and comparing different pieces of music to help participants achieve session-specific goals. The specific structure of the program, including session goals and content based on positive psychotherapy, is detailed in

Table 1.

2.5. Data Analysis

A homogeneity test between the experimental and control groups was conducted prior to the study using an independent t-test. To analyze differences in stress, anxiety, depression, and positive psychological capital across groups (experimental and control) and time points (pre-test, post-test, and follow-up), separate repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted on the DASS 21 subfactors (stress, anxiety, and depression) and the K-PPC subfacotrs (self-efficacy, optimism, hope, resilience, and total score). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0, and an alpha value of 0.05 was set as the significance level.

3. Results

3.1. Homogeneity Test of Participant Characteristics

The homogeneity test results for sociodemographic characteristics, IES-R-K, DASS 21, and K-PPC variables between each group are presented in

Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of the sociodemographic characteristics for any of the items.

3.2. Outcome Measures

3.2.1. DASS 21

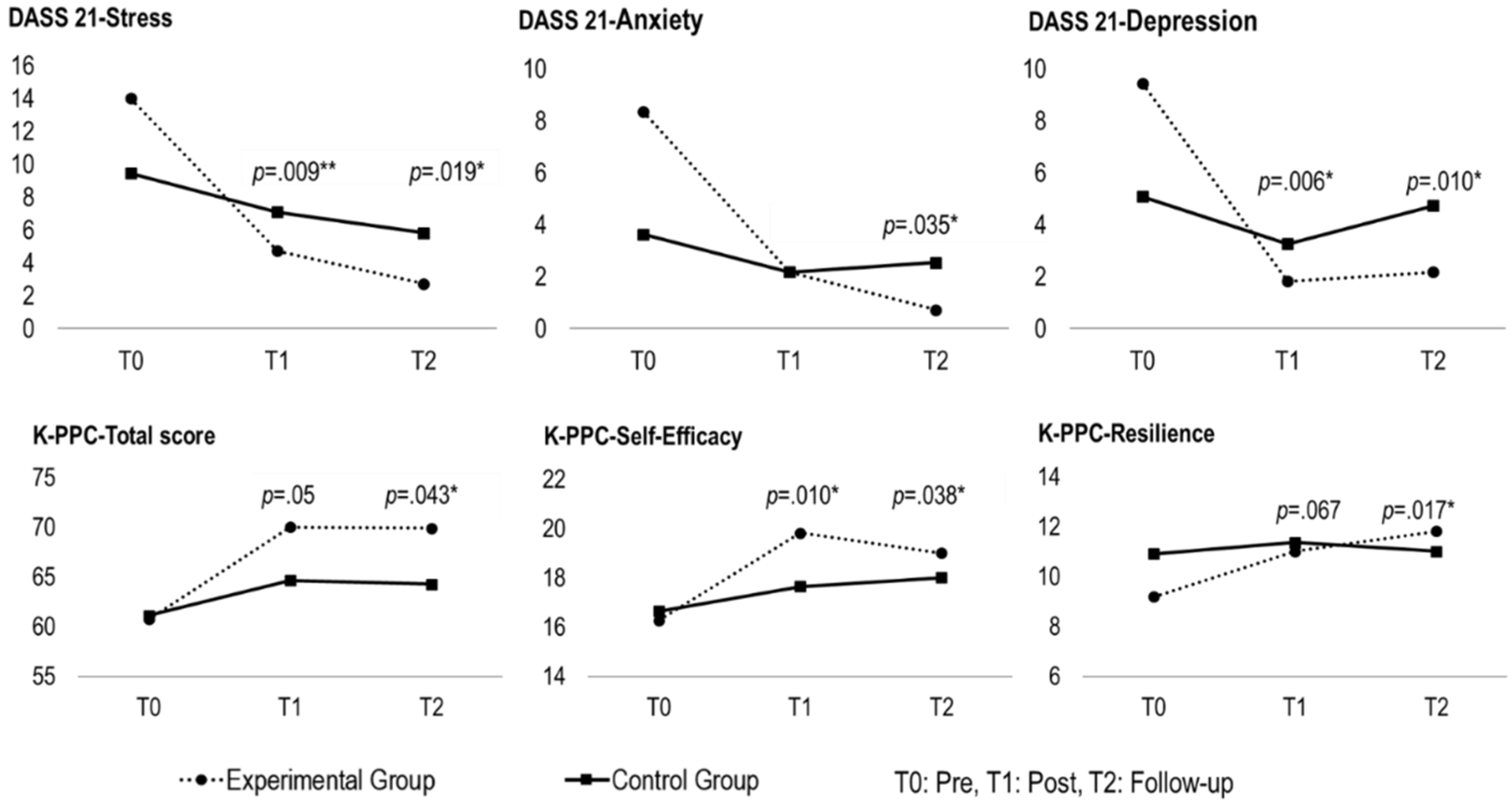

In the analyses of the DASS 21 as a function of group and time, statistically significant main effects of time emerged in stress (F = 19.907, p < .001), anxiety (F = 9.487, p < .01), and depression (F = 10.472, p < .01) variables. In addition, significant group by time interaction effects were observed in stress (F = 5.759, p < .05), anxiety (F = 4.790, p < .01), and depression (F = 5.740, p < .01) variables. The results revealed a significant decrease in stress, anxiety, and depression within the experimental group following the positive psychology-based virtual music therapy, with these improvements sustained at the three-week follow-up. However, no such changes were observed within the control group (Table 3, Figure 2).

3.2.2. K-PPC

The analyses of the K-PPC as a function of group and time revealed statistically significant main effects of time emerged in self- efficacy (F = 14.381,

p < .001), optimism (F = 3.914,

p < .05), hope (F = 7.317,

p < .01), resilience (F = 6.235,

p < .01), and total score (F = 17.235,

p < .001). Additionally, significant group by time interaction effects were found in self- efficacy (F = 3.723,

p < .05), resilience (F = 4.739,

p < .05), and total score (F = 3.740,

p < .05). These results suggest that the positive psychology-based virtual music therapy program effectively enhanced the positive psychological capital of the participants, particularly in terms of self-efficacy and resilience, with these improvements maintained at the three-week follow-up. However, significant changes were not observed in the control group (see

Figure 2 and

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study investigated the effects of positive psychology-based virtual music therapy on stress, anxiety, depression, and positive psychological capital (self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience) among college students experiencing high levels of stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably, participants enrolled in the three-week program experienced significant reductions in stress, anxiety, and depression, coupled with notable enhancements in positive psychological capital, with a particular emphasis on self-efficacy and resilience.

The participants in this study were undergraduate students who showed a tendency for post-traumatic stress disorder on the IES-R-K, indicating their vulnerability to stress. High stress levels in a restricted environment can lead to negative thoughts and emotions and can limit the perspective of looking at current problems in a positive light and thinking about a hopeful future. The students in this study also highlighted the challenges they encountered while adjusting to the educational and technological changes brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. They expressed feelings of stress and fatigue from coping with increased volumes of online information and assignments, as well as the considerable time spent in front of computer screens on a daily basis. Consequently, reports of impaired mental health among college students during the COVID-19 era have been consistently documented on a global scale [

6,

7,

8].

Primarily, the observed reductions in stress, anxiety, and depression in the experimental group align with previous research highlighting the therapeutic benefits of music therapy in promoting emotional well-being and reducing psychological distress [

32,

33,

34,

35]. In this study, listening to music and participating in diverse musical activities designed to offer enjoyable and meaningful experiences throughout the 15 sessions proved to be effective strategies for coping with negative emotions. In each session, the participants were encouraged to write down their honest feelings and thoughts about the given theme on a worksheet and apply them to their daily lives as actions. Previous research has reported the positive impact of expressive writing on reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, thus supporting the effectiveness of the intervention in this study [

36].

For college students, heightened depressive symptoms and decreased well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic have been linked to feelings of social isolation and loneliness [

37]. In this context, engaging in virtual music therapy sessions may have offered opportunities for participants to connect with the therapist and perceive themselves as part of a collective endeavor with others, even if not physically present. This sense of social connection and belongingness cultivated during the sessions could have served as a protective factor against the negative psychological impacts of social isolation and loneliness. Studies have suggested that practices such as meditation, mindfulness sessions, engaging in phone or online counseling, and participating in digital mental health programs can serve as effective alternatives for alleviating psychological distress and feelings of isolation [

38,

39]

This study also demonstrated the effectiveness of the positive psychology-based virtual music therapy program in enhancing positive psychological capital, particularly resilience and self-efficacy. Previous studies on the impact of music-based interventions on resilience and self-efficacy have not been abundant. In addition, existing studies present inconsistent findings regarding whether music therapy significantly enhances resilience and self-efficacy, with study participants primarily comprised of clinical populations, particularly children or adolescents [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. However, it appears that the elements of positive psychology blended into the music therapy program in this study resulted in a significant improvement in resilience and efficacy of the undergraduate participants. As presented in

Table 1, the program was designed not only to provide relaxation and enjoyment through music but also to enable participants to reflect on past, present, and future events, emotions, and hopes, as well as their personal strengths and relationships through various activities. Such an approach, combining elements of positive psychotherapy with the therapeutic use of music to actively engage participants in activities, might be more conducive to enhancing overall positive psychological capital, including resilience and self-efficacy, compared to the traditional receptive music therapy approach, which focuses on the passive experience of listening to or experiencing music. This interpretation can be supported by previous studies which have reported the effects of positive psychotherapy on establishing a psychologically safe environment, increasing social connectedness, raising internal hope, and modifying perceptions of coping strategies, ultimately leading to behavioral changes [

14,

15,

16,

17].

The experimental group participants in this study received 15 sessions' worth of video clips and worksheets at the outset of the research. They were instructed to complete one session per weekday over a three-week period, granting them autonomy to choose their preferred time and location to perform specific tasks. This emphasis on self-regulation aligns with research suggesting that autonomy-supportive environments can bolster resilience and self-efficacy through enhanced motivation and perceived competence [

47,

48]. Furthermore, adhering to a daily routine has a positive impact on psychological resilience [

49]. Engaging in any regular activity voluntarily can provide a sense of routine and structure, helping individuals cope with negative emotions more effectively. Therefore, participating in the virtual music therapy program as a structured daily routine might have promoted feelings of control and predictability, thereby increasing resilience and self-efficacy.

The present study has several limitations. Since this program delivered music therapy content to participants through pre-recorded video files, it may have been somewhat limited in terms of its therapeutic effectiveness due to communication constraints, such as the therapist's inability to directly interact with and offer immediate feedback to the client. Therefore, future research should examine how the impacts of positive psychology-based music therapy on mental health differ from the outcomes of this study when delivered in a virtual environment where therapists and clients can interact in real time. In this study, participants were given autonomy to engage in the program at their preferred time and location. However, despite significant improvement, it's unclear whether this autonomy played a role in enhancing (or diminishing) the effectiveness of the intervention itself. Future research could provide stronger evidence by comparing outcomes when participants have autonomy versus when they adhere to a researcher-determined schedule. Additionally, while worksheets were utilized in the program, their contents were not analyzed or provided with feedback in this study. Incorporating qualitative analysis of worksheet data in future research would yield valuable insights.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study suggest the potential of positive psychology-based virtual music therapy as a promising and scalable intervention for addressing stress, anxiety, depression, and enhancing positive psychological resources among college students. By leveraging technology and evidence-based therapeutic approaches, such interventions have the potential to empower individuals to cultivate resilience and well-being, particularly in challenging circumstances such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The scalability of this approach is further facilitated by the nature of the program, which allows participants to choose their preferred time and place of participation in a virtual setting. This flexibility may enhance accessibility and effectiveness, making it a valuable tool for promoting mental health in diverse populations.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study delved into the effects of positive psychology-based virtual music therapy on stress, anxiety, depression, and positive psychological capital among college students amidst the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic. The results illuminated significant reductions in stress, anxiety, and depression alongside notable enhancements in positive psychological capital, particularly in terms of self-efficacy and resilience among participants. These findings are significant given the documented challenges faced by college students during the pandemic, including increased stress levels and mental health issues.

The observed positive outcomes align with previous research highlighting the therapeutic benefits of music therapy in promoting emotional well-being. Moreover, the integration of expressive writing and virtual social connection within the therapy sessions contributed to the effectiveness of the intervention. The emphasis on positive psychology principles, combined with the therapeutic use of music, proved instrumental in fostering resilience and self-efficacy among participants, a notable contribution given the limited research in this area.

Despite the promising results, the study acknowledges several limitations, including the lack of real-time interaction with a therapist and the autonomy given to participants in engaging with the program. Future research should explore these aspects further to enhance the efficacy of virtual music therapy interventions.

In conclusion, this study underscores the potential of positive psychology-based virtual music therapy as a scalable intervention for addressing mental health challenges among college students, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. By leveraging technology and evidence-based therapeutic approaches, such interventions offer a flexible and accessible means of promoting resilience and well-being in diverse populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and H.L.; methodology, J.H. and S.L.; software, J.H. and T.K.; validation, J.H. and S.L.; formal analysis, J.H. and T.K.; investigation, J.H. and H.L; resources, J.H. and S.L.; data curation, J.H. and S.L; writing—original draft preparation, J.H. and T.K.; writing—review and editing, H.L. and S.L.; visualization, J.H. and T.K.; supervision, H.L. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board for Ethics in Human Research at Wonkwang University (approval no. WKIRB-202102-HR-005).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baud, D., Qi, X., Nielsen-Saines, K., Musso, D., Pomar, L., & Favre, G. (2020). Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection. The Lancet infectious diseases, 20(7), 773. [CrossRef]

- Wasim, A., Truong, J., Bakshi, S., & Majid, U. (2023). A systematic review of fear, stigma, and mental health outcomes of pandemics. Journal of Mental Health, 32(5), 920-934. [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, R., Agrawal, A., & Sharma, M. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of neurosciences in rural practice, 11(04), 519-525. [CrossRef]

- Smit, A. N., Juda, M., Livingstone, A., U, S. R., & Mistlberger, R. E. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 social-distancing on sleep timing and duration during a university semester. PloS one, 16(4), e0250793.

- Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., ... & Kessler, R. C. (2018). WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of abnormal psychology, 127(7), 623.

- Husky, M. M., Kovess-Masfety, V., & Swendsen, J. D. (2020). Stress and anxiety among university students in France during Covid-19 mandatory confinement. Comprehensive psychiatry, 102, 152191. [CrossRef]

- Gritsenko, V., Skugarevsky, O., Konstantinov, V., Khamenka, N., Marinova, T., Reznik, A., & Isralowitz, R. (2021). COVID 19 fear, stress, anxiety, and substance use among Russian and Belarusian university students. International journal of mental health and addiction, 19, 2362-2368. [CrossRef]

- Konstantopoulou, G., Pantazopoulou, S., Iliou, T., & Raikou, N. (2020). Stress and depression in the exclusion of the Covid-19 pandemic in Greek university students. European Journal of Public Health Studies, 3(1), 91-99. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T., & Seligman, M. P. (2018). 긍정심리치료: 치료자 매뉴얼 [Positive Psychotherapy: Clinician Manual]. (우문식, 이미정). Oxford University Press.

- McDowell, I. (2010). Measures of self-perceived well-being. Journal of psychosomatic research, 69(1), 69-79. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Y. (2020). A convergence study of stress caused by the epidemic of COVID-19, quality of life and positive psychological capital. Journal of the Korea Convergence Society, 11(6), 423-431. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. J. (2020). An Analysis of Positive Psychological Capital Influencing Emotional Reactions of College Students Under COVID-19. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 21, 11(6), 2885-2899. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. I., Starr, L. R., & Hershenberg, R. (2017). Responses to positive affect in daily life: Positive rumination and dampening moderate the association between daily events and depressive symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 39, 412-425. [CrossRef]

- Lee Duckworth, A., Steen, T. A., & Seligman, M. E. (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 629-651. [CrossRef]

- Magyar-Moe, J. L., Owens, R. L., & Conoley, C. W. (2015). Positive psychological interventions in counseling: What every counseling psychologist should know. The Counseling Psychologist, 43(4), 508-557. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H. Y., Seo, S. B., & Park, J. Y. (2019). Effects of Positive Psychology-Based Music Therapy on Family Members' Attitudes Towards Gambling Addicts. Journal of the Korea Convergence Society, 10(6), 269-279. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, S. Y. (2019). Integrating positive psychology and elements of music therapy to alleviate adolescent anxiety. Research on Social Work Practice, 29(6), 663-676. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N. A. (2015). Music therapy and chronic mental illness: Overcoming the silent symptoms. Music Therapy Perspectives, 33(2), 90-96. [CrossRef]

- Ziv, N., Chaim, A. B., & Itamar, O. (2011). The effect of positive music and dispositional hope on state hope and affect. Psychology of Music, 39(1), 3-17. [CrossRef]

- Croom, A. M. (2015). Music practice and participation for psychological well-being: A review of how music influences positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. Musicae Scientiae, 19(1), 44-64. [CrossRef]

- Chirico, A., Maiorano, P., Indovina, P., Milanese, C., Giordano, G. G., Alivernini, F., ... & Giordano, A. (2020). Virtual reality and music therapy as distraction interventions to alleviate anxiety and improve mood states in breast cancer patients during chemotherapy. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 235(6), 5353-5362. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, F., Scarlata, E., Baroni, M., Gentile, E., Puntillo, F., Brienza, N., & Gesualdo, L. (2020). Receptive music therapy to reduce stress and improve wellbeing in Italian clinical staff involved in COVID-19 pandemic: A preliminary study. The Arts in psychotherapy, 70, 101688. [CrossRef]

- Bompard, S., Liuzzi, T., Staccioli, S., D’Arienzo, F., Khosravi, S., Giuliani, R., & Castelli, E. (2023). Home-based music therapy for children with developmental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 29(3), 211-216. [CrossRef]

- Eun, H. J., Kwon, T. W., Lee, S. M., Kim, T. H., Choi, M. R., & Cho, S. J. (2005). A study on reliability and validity of the Korean Version of Impact of Event Scale-Revised. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association, 44, 303-310.

- M. Horowitz, N. Wilner, W. Alvarez, Impact of event scale: A measure of subjective stress, Psychosom. Med. 41 (1979) 209-218.

- Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (1997). The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. In J. P. Wilson & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 399-411). New York: Guilford Press.

- Lee, E. H., Moon, S. H., Cho, M. S., Park, E. S., Kim, S. Y., Han, J. S., & Cheio, J. H. (2019). The 21-item and 12-item versions of the depression anxiety stress scales: psychometric evaluation in a Korean population. Asian Nursing Research, 13(1), 30-37. [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335-343. [CrossRef]

- Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227-239. [CrossRef]

- Lim, T. H. (2014). Validation of the Korean version of positive psychological capital (K-PPC). Journal of Coaching Development, 16(3), 157-166.

- Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 339-366. [CrossRef]

- Umbrello, M., Sorrenti, T., Mistraletti, G., Formenti, P., Chiumello, D., & Terzoni, S. (2019). Music therapy reduces stress and anxiety in critically ill patients: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Minerva Mnestesiologica, 85(8), 886-898.

- de la Rubia Ortí, J. E., García-Pardo, M. P., Iranzo, C. C., Madrigal, J. J. C., Castillo, S. S., Rochina, M. J., & Gascó, V. J. P. (2018). Does music therapy improve anxiety and depression in alzheimer's patients?. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 24(1), 33-36. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A. Z., Shahabi, T., & Panah, F. M. (2011). An evaluation of the effect of group music therapy on stress, anxiety and depression levels in nursing home residents. Canadian Journal of Music Therapy, 17(1). 55–68.

- Hwang, E. Y., & Oh, S. H. (2013). A comparison of the effects of music therapy interventions on depression, anxiety, anger, and stress on alcohol-dependent clients: A pilot study. Music and Medicine, 5(3), 136-144. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. (2023). The delayed, durable effect of expressive writing on depression, anxiety and stress: A meta-analytic review of studies with long-term follow-ups. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(1), 272-297. [CrossRef]

- Holm-Hadulla, R. M., Wendler, H., Baracsi, G., Storck, T., & Herpertz, S. C. (2023). Depression and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic in a student population: the effects of establishing and relaxing social restrictions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, DOI:1200643. /10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1200643.

- Pizzoli, S. M. F., Marzorati, C., Mazzoni, D., & Pravettoni, G. (2020). An internet-based intervention to alleviate stress during social isolation with guided relaxation and meditation: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 9(6), e19236. [CrossRef]

- Farris, S. R., Grazzi, L., Holley, M., Dorsett, A., Xing, K., Pierce, C. R., ... & Wells, R. E. (2021). Online mindfulness may target psychological distress and mental health during COVID-19. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 10, 21649561211002461. [CrossRef]

- Blauth, L., & Oldfield, A. (2022). Research into increasing resilience in children with autism through music therapy: Statistical analysis of video data. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 31(5), 454-480. [CrossRef]

- Burns, D. S., Robb, S. L., & Haase, J. E. (2009). Exploring the feasibility of a therapeutic music video intervention in adolescents and young adults during stem-cell transplantation. Cancer Nursing, 32(5), E8-E16. [CrossRef]

- Choi, A. N., & Cha, E. S. (2007). The Effect of Group Music Therapy on the Emotional Stabilisation and the Self-Efficacy of Juvenile Delinquents. Journal of Families and Better Life, 25(5), 1-14.

- Letwin, L., & Silverman, M. J. (2017). No between-group difference but tendencies for patient support: A pilot study of a resilience-focused music therapy protocol for adults on a medical oncology/hematology unit. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 55, 116-125. [CrossRef]

- Lim, H. A., & Befi, C. M. (2014). Music therapy career aptitude and generalized self-efficacy in music therapy students. Journal of music therapy, 51(4), 382-395. [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M. J. (2014). Effects of music therapy on drug avoidance self-efficacy in patients on a detoxification unit: A three-group randomized effectiveness study. Journal of addictions nursing, 25(4), 172-181. [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M. J. (2019). Music therapy for coping self-efficacy in an acute mental health setting: A randomized pilot study. Community Mental Health Journal, 55, 615-623. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The" what" and" why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268. [CrossRef]

- Ataii, M., Saleh-Sedghpour, B., Asadzadeh-Dahraei, H., & Sadatee-Shamir, A. (2021). Effect of Self-regulation on Academic Resilience Mediated by Perceived Competence. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 15(3). 156-161. [CrossRef]

- Suckow, E. J., Henderson-Arredondo, K., Hildebrand, L., Jankowski, S. R., & Killgore, W. D. (2023). 70 Daily Routine and Psychological Resilience. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 29(s1), 579-580. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).