Submitted:

02 July 2024

Posted:

03 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Melbourne Decision-Making Questionnaire (MDMQ)

2.2.2. General Decision-Making Style (GDMS)

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive, Distribution Frequencies Values, Internal Consistency, and Inter-Correlations

3.2. Exploratory Matrix Structure of the MDMQ and the GDMS

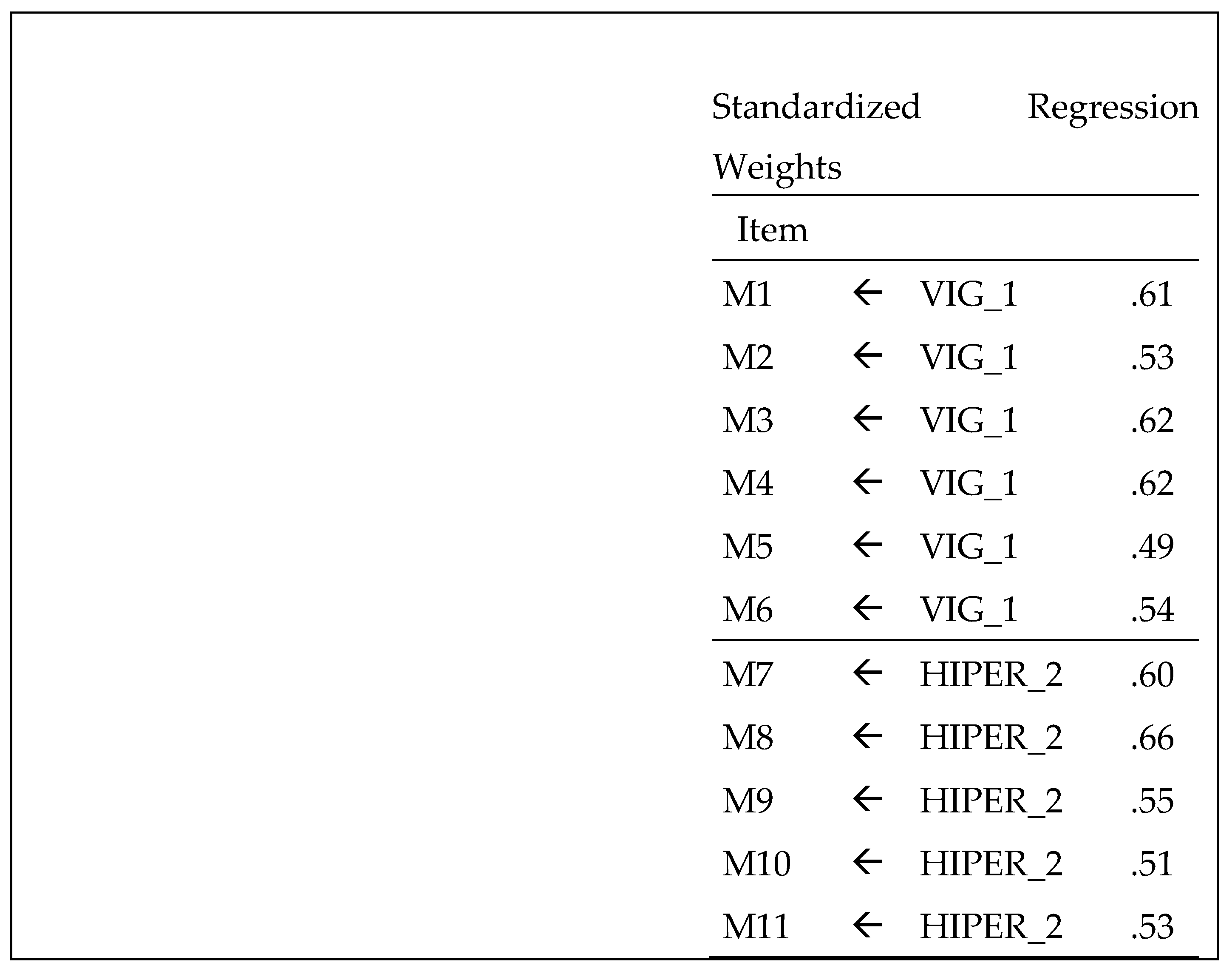

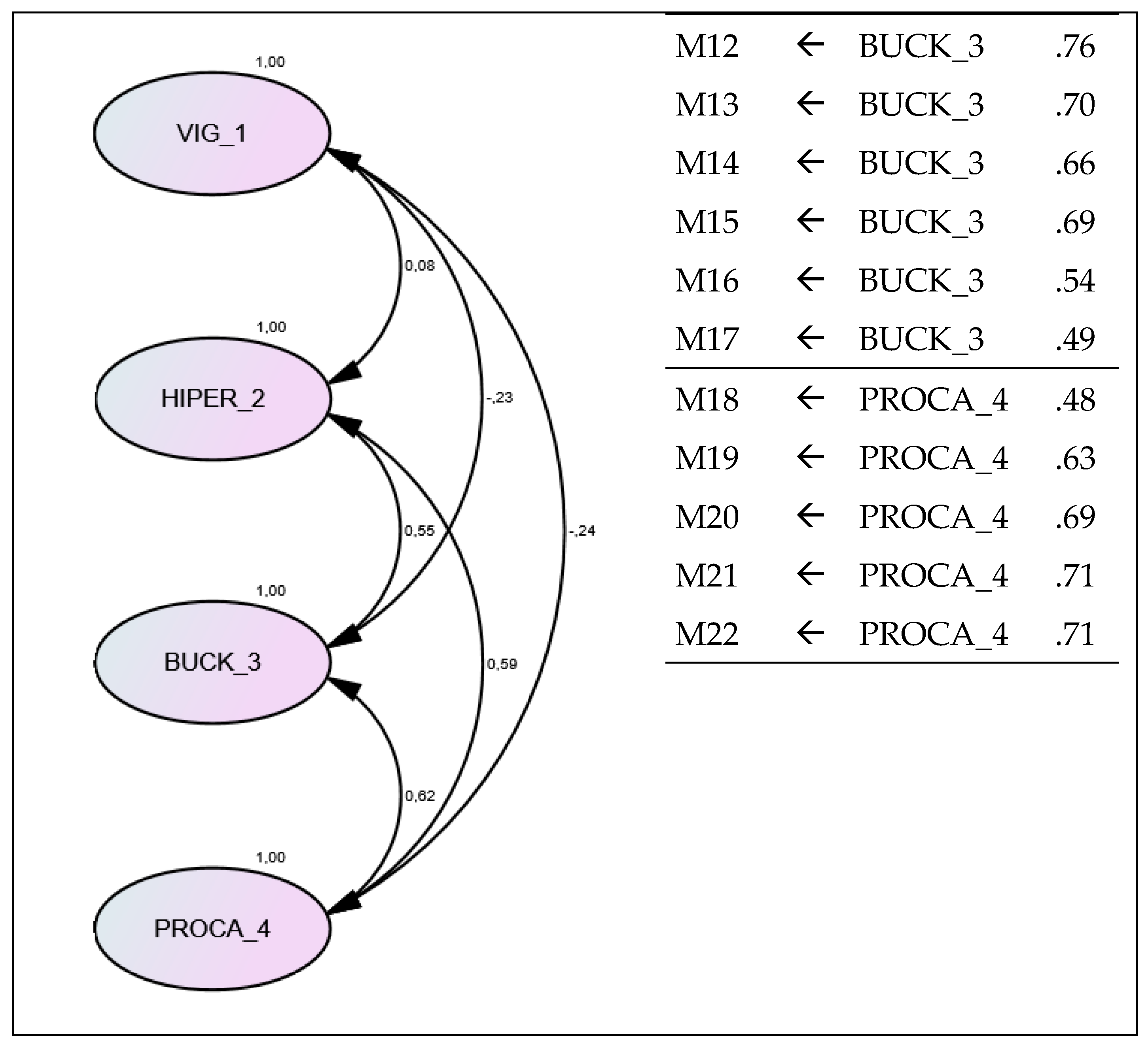

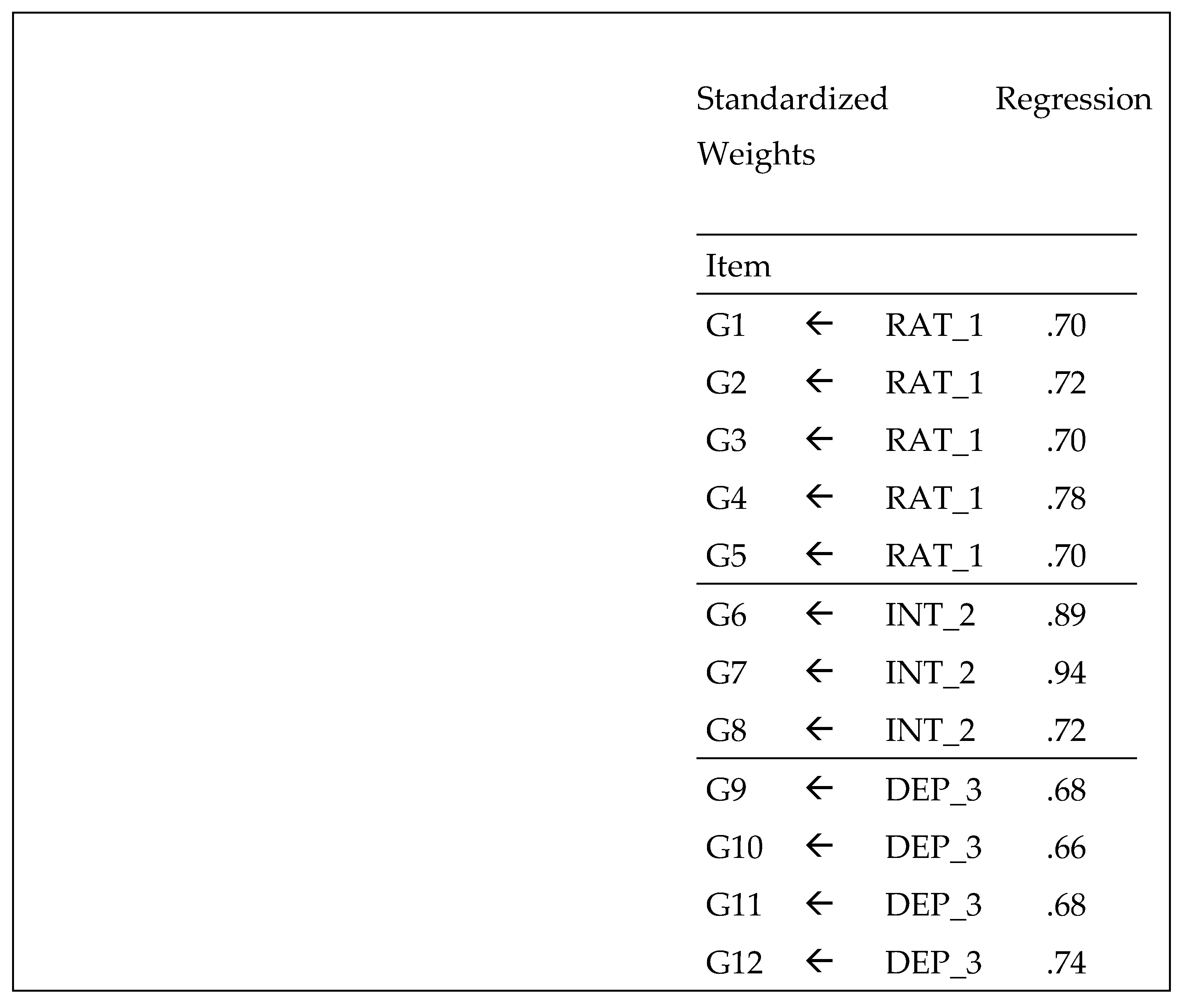

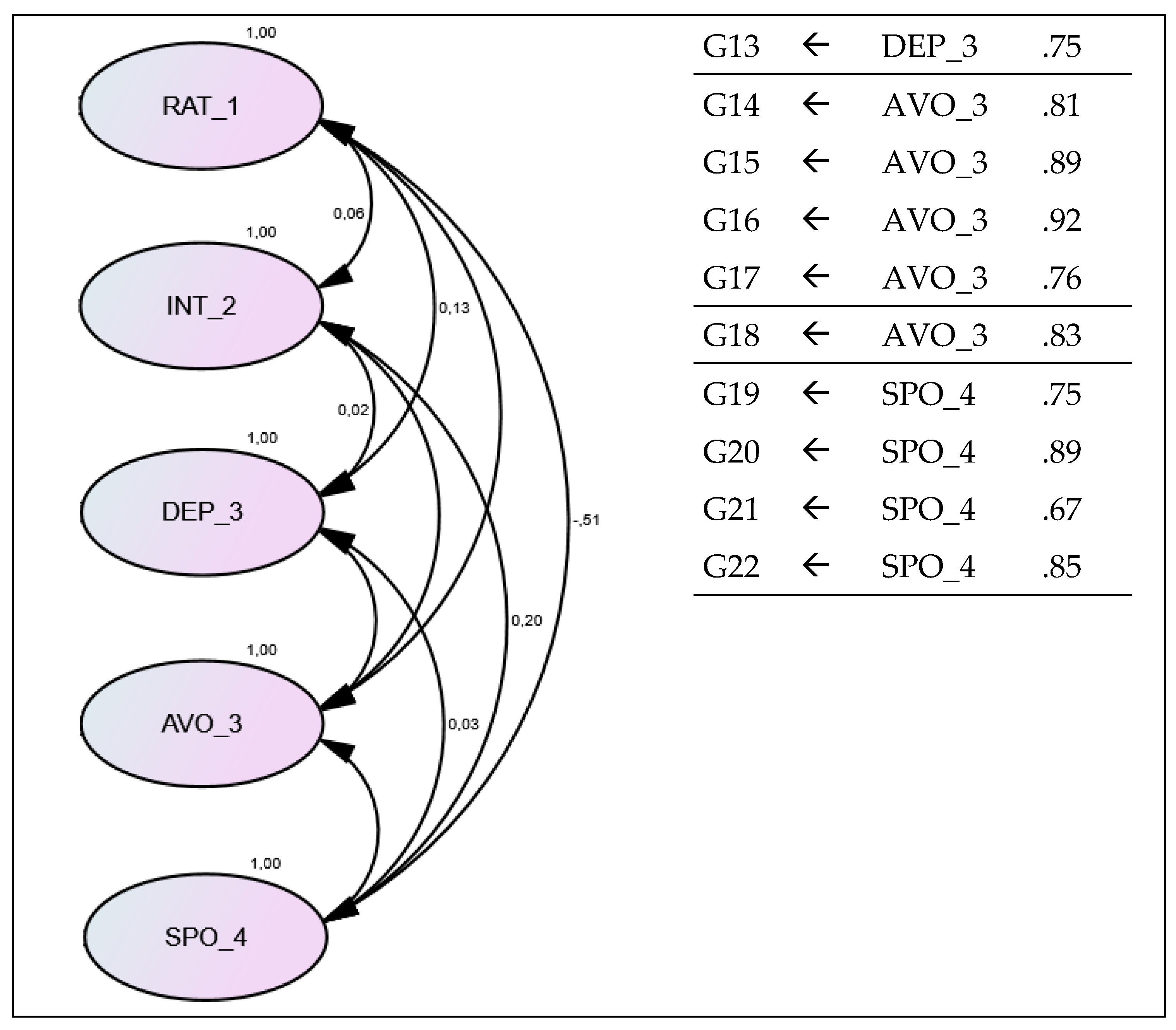

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

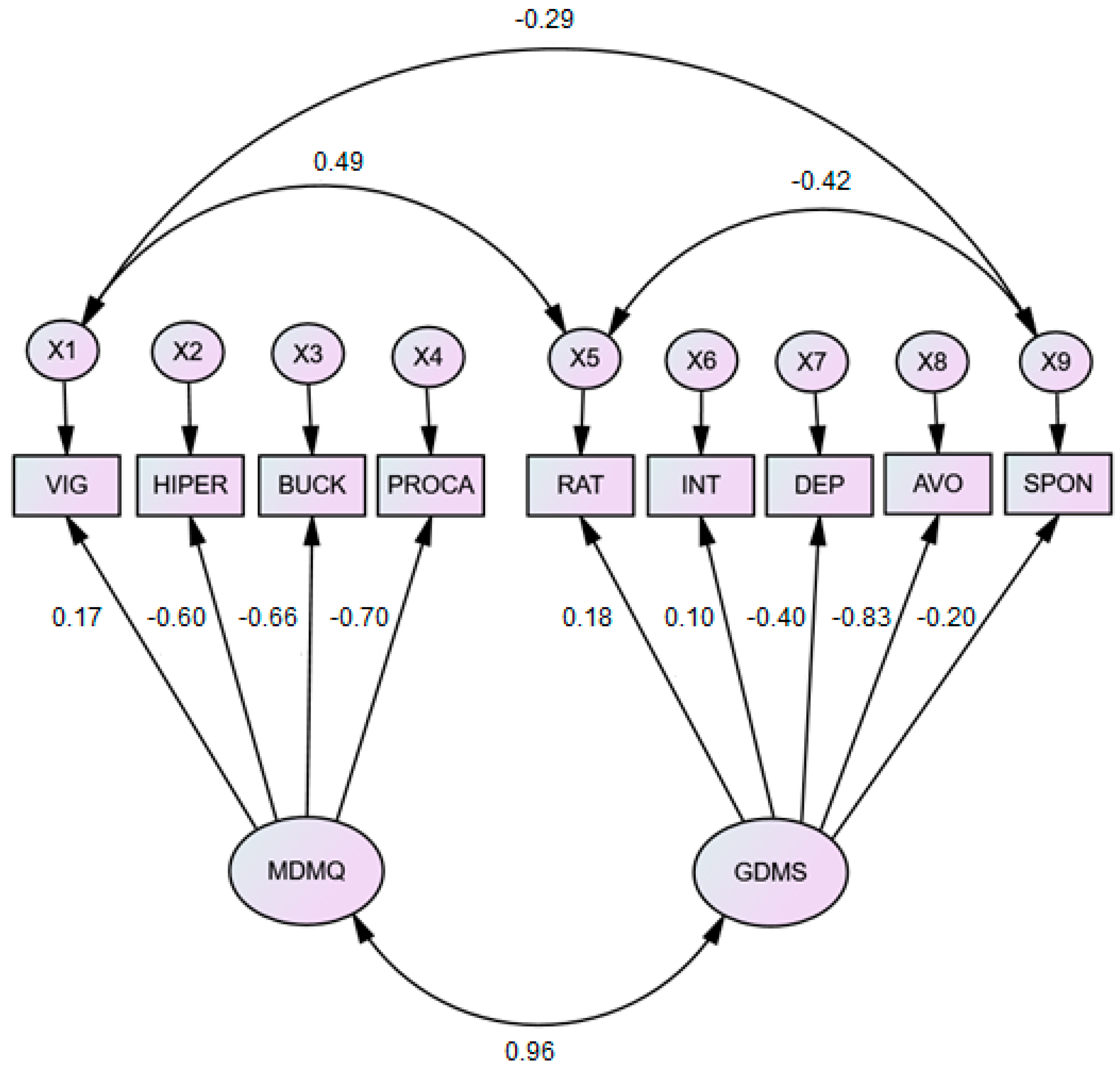

3.4. MDMQ and GDMS Convergence Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Consent to participate

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Ethical Approval

References

- Mann, L.; Radford, M.; Burnett, P.; Ford, S.; Bond, M.; Leung, K.; Yang, K.-S. Cross-cultural differences in self-reported decision-making style and confidence. Int. J. Psychol. 1998, 33, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janis, I.L.; Mann, L. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment; Free Press: Mumbai, India, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff, C.E. Age, time, and decision making: From processing speed to global time horizons. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1235, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, R.; Strough, J.N.; Parker, A.M.; Bruine de Bruin, W. Variations in decision-making profiles by age and gender: A cluster-analytic approach. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 85, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckenooghe, D.; Vanderheyden, K.; Mestdagh, S.; Van Laethem, S. Cognitive motivation correlates of coping style in decisional conflict. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 2007, 141, 605–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.S.; Zhang, R.R.; Lan, Y.; Li, Z.M.; Li, Y.H. Questionnaire-based maladaptive decision coping patterns involved in binge eating among 1013 college students. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alacreu-Crespo, A.; Fuentes, M.C.; Abad-Tortosa, D.; Cano-López, I.; González, E.; Serrano, M.Á. Spanish validation of General Decision-Making Style scale: Sex invariance, sex differences and relationships with personality and coping styles. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2019, 14, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M.; Arani, M.R. Relationship between five personality factors with decision making styles of coaches. Sport Sci. 2017, 10, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Urieta, P.; Aluja, A.; Garcia, L.F.; Balada, F.; Lacomba, E. Decision-making and the alternative five factor personality model: Exploring the role of personality traits, age, sex, and social position. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 717705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urieta, P.; Sorrel, M.A.; Aluja, A.; Balada, F.; Lacomba, E.; García, L.F. Exploring the relationship between personality, decision-making styles, and problematic smartphone use. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 14250–14267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren, T.E. Development of a measure of decision-making styles. In Proceedings of the 72nd Annual Meeting of the Midwestern Psychological Association, Chicago, IL, USA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin, W.; Parker, A.M.; Fischhoff, B. Individual differences in adult decision-making competence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 938–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leykin, Y.; DeRubeis, R.J. Decision-making styles and depressive symptomatology: Development of the Decision Styles Questionnaire. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2010, 5, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Shih, S.I.; Mohammed, S. The development and validation of the rational and intuitive decision styles scale. J. Pers. Assess. 2016, 98, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uziel, L.; Baumeister, R.F. The self-control irony: Desire for self-control limits exertion of self-control in demanding settings. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebert, J.; Kunz, R. Developing and validating the multidimensional proactive decision-making scale. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 249, 864–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Decision-making style: The development and assessment of a new measure. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1995, 55, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, L.P.; Alvarez, M.J.; Roberto, M.S.; Ferreira, J.A. Validation and invariance across age and gender for the Melbourne Decision-Making Questionnaire in a sample of Portuguese adults. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2020, 15, 135–148, http://hdl.handle.net/10400.8/4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, L.; Burnett, P.; Radford, M.; Ford, S. The Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire: An instrument for measuring patterns for coping with decisional conflict. J. Behav. Decis.Mak. 1997, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Heredia, R.A.S.; Arocena, F.L.; Gárate, J.V. Decision-making patterns, conflict styles, and self-esteem. Psicothema 2004, 16, 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J.G.; Reddie, L. Decisional style and self-reported Email use in the workplace. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 2414–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, H.M.S. Personality and decision-making styles of university students. J. IndianAcad. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 40, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, M.J.; Brousseau, K.E.; Hunsaker, P.L. The Dynamic Decision Maker; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, L.; An organization of learning styles theory and constructs. Educ. Res. Inf. Cent. (ERIC) 1983, 2, 2–28. Available online: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED235185.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Bailly, N.; Ilharragorry-Devaux, M.L. Adaptation et validation en langue française d’une échelle de prise de décision. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2011, 43, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colakkadioglu, O.; Deniz, M.E. Study on the validity and reliability of Melbourne Decision Making Scale in Turkey. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 10, 1434–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nota, L.; Soresi, S. Adattamento italiano del Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire di Leon Mann. G. Ital. Psicol. Orientam. 2000, 1, 38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kornilova, T.V. Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire: A Russian adaptation. Psikhologicheskie Issledovaniya 2013, 6, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Tipandjan, A. Cross-cultural study on decision making of German and Indian university students. Ph.D. Thesis, Technischen Universität Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baiocco, R.; Laghi, F.; D’Alessio, M. Decision making style among adolescents: Relationship with sensation seeking and locus of control. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curşeu, P.L.; Schruijer, S.G.L. Decision styles and rationality: An analysis of the predictive validity of the general decision-making style inventory. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2012, 72, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavolar, J.; Orosová, O. Decision-making styles and their associations with decision-making competencies and mental health. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2015, 10, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, A.J.; Reeve, C.L.; Bonaccio, S. Assessing decision-making style in French-speaking populations: Translation and validation of the general decision-making style questionnaire. Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. 2016, 66, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Soyez, K.; Gurtner, S. Adapting Scott and Bruce’s general decision-making style inventory to patient decision making in provider choice. Med. Decis. Mak. 2015, 35, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Campo, C.; Pauser, S.; Steiner, E.; Vetschera, R. Decision making styles and the use of heuristics in decision making. J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 86, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A GlobalPerspective; Pearson Education International: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen, B.; Kaplan, D. A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of nonnormal Likert variables. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1985, 38, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural equation models with non-normal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, J.L. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 1965, 30, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, M.E.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Dimensionality assessment of ordered polytomous items with parallel analysis. Psychol. Methods 2011, 16, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buja, A.; Eyuboglu, N. Remarks on parallel analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1992, 27, 509–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. A simulation-based scaled test statistic for assessing model-data fit in least-squares unrestricted factor-analysis solutions. Technical report, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, 2022.

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. FACTOR: a computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Behav. Res. Methods 2006, 38, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos 26.0 User's Guide; IBM SPSS: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T.; Fiske, D.W. Convergent and Discriminant Validation by the Multitrait-multimethod Matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1959, 56, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thunholm, P. Decision-making style: Habit, style or both? Pers. Individ. Dif. 2004, 36, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluja, A.; Garcia, L.F.; Rossier,; Ostendorf, F. ; Glicksohn, J.; Oumar, B.; et al. Dark triad traits, social position, and personality: A cross-cultural study. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2002, 53, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, G.; Book, A.; Visser, B.A.; Volk, A.A.; Ashton, M.C.; Lee, K. [1] Is the dark triad common factor distinct from low honesty-humility? J. Res. Pers. 2018, 73, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (n = 1,562) | M | SD | S | K | α | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDMQ | ||||||||||||||

| 1. Vigilance | 9.28 | 2.20 | -.94 | .99 | .74 | -.31 | -.17 | .00 | -.01 | .50 | -.17 | -.15 | .07 | 1 |

| 2. Hypervigilance | 4.74 | 2.34 | .17 | -.38 | .71 | .04 | .45 | .29 | -.11 | -.01 | .47 | .41 | 1 | |

| 3. Buck-passing | 5.05 | 2.67 | .37 | -.10 | .79 | .06 | .52 | .32 | -.17 | -.12 | .46 | 1 | ||

| 4. Procrastination | 3.21 | 2.34 | .64 | .01 | .78 | .14 | .60 | .24 | -.06 | -.14 | 1 | |||

| GDMS | ||||||||||||||

| 5. Rational | 3.99 | .65 | -.63 | .80 | .84 | -.44 | -.19 | .11 | .06 | 1 | ||||

| 6. Intuitive | 3.68 | .87 | -.51 | .13 | .89 | .20 | -.07 | .04 | 1 | |||||

| 7. Dependent | 3.47 | .82 | -.42 | .00 | .83 | -.01 | .32 | 1 | ||||||

| 8. Avoidant | 2.37 | .97 | .53 | -.38 | .92 | .23 | 1 | |||||||

| 9. Spontaneous | 2.31 | .89 | .61 | .02 | .87 | 1 |

| MDMQ1 | GDMS2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Real data | Mean RAND | 95 PCT RAND | Component | Real data | Mean RAND | 95 PCT RAND |

| Eigenvalues | Eigenvalues | ||||||

| 1 | 5.27422* | 1.21685 | 1.24935 | 1 | 5.29357* | 1.21785 | 1.25389 |

| 2 | 2.77683* | 1.18202 | 1.20613 | 2 | 3.98406* | 1.18216 | 1.20514 |

| 3 | 1.63456* | 1.15615 | 1.17912 | 3 | 1.88839* | 1.15578 | 1.17578 |

| 4 | 1.28210* | 1.13212 | 1.15250 | 4 | 1.88839* | 1.13285 | 1.15060 |

| 5 | 0.95638 | 1.11097 | 1.12864 | 5 | 1.41550* | 1.11058 | 1.12707 |

| … | … | … | … | 6 | 0.68454 | 1.09074 | 1.10641 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| 22 | 0.35966 | 0.80128 | 0.82461 | 22 | 0.14727 | 0.80160 | 0.82372 |

| Advised number of factors: 4 | Advised number of factors: 5 | ||||||

| MDMQ1 | GDMS2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | I | II | III | IV | H2 | I | II | III | IV | V | H2 | |

| 1 | .71 | -.02 | -.07 | .02 | .51 | .73 | .01 | .10 | -.10 | -.17 | .58 | |

| 2 | .64 | .10 | .00 | .03 | .42 | .78 | .03 | .02 | -.09 | -.12 | .63 | |

| 3 | .72 | -.10 | -.03 | -.07 | .53 | .75 | .03 | -.01 | -.11 | -.14 | .60 | |

| 4 | .68 | .07 | -.07 | -.07 | .48 | .80 | -.02 | .07 | .03 | -.23 | .69 | |

| 5 | .55 | -.10 | -.13 | -.22 | .38 | .75 | .08 | .06 | -.10 | -.12 | .60 | |

| 6 | .62 | .24 | .05 | -.08 | .45 | .07 | .92 | -.03 | -.05 | .09 | .85 | |

| 7 | -.05 | .67 | .15 | .15 | .49 | .03 | .93 | .00 | -.04 | .09 | .88 | |

| 8 | .01 | .68 | .14 | .18 | .51 | .03 | .83 | .11 | -.03 | .12 | .72 | |

| 9 | .15 | .68 | .07 | .07 | .49 | -.02 | .01 | .73 | .23 | -.02 | .59 | |

| 10 | .00 | .53 | .31 | .04 | .38 | .03 | -.03 | .74 | .12 | -.13 | .58 | |

| 11 | .07 | .63 | .07 | .16 | .43 | .07 | .06 | .76 | .07 | .03 | .59 | |

| 12 | -.09 | .12 | .64 | .39 | .58 | .09 | -.01 | .79 | .07 | .01 | .64 | |

| 13 | -.10 | .15 | .62 | .30 | .50 | .06 | .06 | .78 | .16 | .06 | .64 | |

| 14 | -.10 | .08 | .77 | .17 | .64 | -.10 | -.08 | .19 | .82 | .04 | .73 | |

| 15 | -.09 | .26 | .66 | .19 | .55 | -.05 | -.04 | .15 | .89 | .04 | .82 | |

| 16 | -.06 | .06 | .74 | .10 | .56 | -.07 | -.04 | .16 | .90 | .05 | .85 | |

| 17 | .10 | .13 | .51 | -.12 | .30 | -.12 | .02 | .05 | .81 | .19 | .70 | |

| 18 | .00 | .37 | .04 | .41 | .39 | -.08 | -.02 | .17 | .84 | .10 | .76 | |

| 19 | -.10 | .32 | .07 | .63 | .52 | -.21 | .05 | -.03 | .18 | .79 | .70 | |

| 20 | -.04 | .16 | .14 | .75 | .60 | -.24 | .13 | .06 | .19 | .82 | .79 | |

| 21 | -.15 | .14 | .15 | .74 | .62 | -.14 | .11 | -.08 | -.07 | .80 | .68 | |

| 22 | -.06 | .08 | .26 | .75 | .64 | -.23 | .09 | .03 | .14 | .83 | .77 | |

| I | II | III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avoidant | .79 | -.24 | .00 |

| Procrastination | .76 | -.19 | -.02 |

| Hypervigilance | .74 | .10 | -.06 |

| Buck-passing | .74 | -.12 | -.20 |

| Dependent | .59 | .20 | .26 |

| Rational | -.03 | .84 | .12 |

| Vigilance | -.05 | .77 | .03 |

| Spontaneous | .10 | -.67 | .40 |

| Intuitive | -.09 | -.01 | .92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).