Submitted:

03 July 2024

Posted:

04 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical and Methodological Contributions

1.2. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Prejudice Avoidance

3.1.1. Methods

3.1.2. Outcomes

3.1.3. Moderators

3.1.4. Critical Summary

3.2. Universal Orientation

3.2.1. Methods

3.2.3. Outcomes

3.2.4. Moderators

3.2.5. Critical Summary

3.3. Concern for Others

3.3.1. Methods

3.3.2. Outcomes

3.3.3. Critical Summary

3.4. Positive Expression

3.4.1. Methods

3.4.2. Outcomes

3.4.3. Critical Summary

3.5. Low Social Dominance Orientation

3.5.1. Methods

3.5.2. Outcomes

3.5.3. Moderators

3.5.4. Critical Summary

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

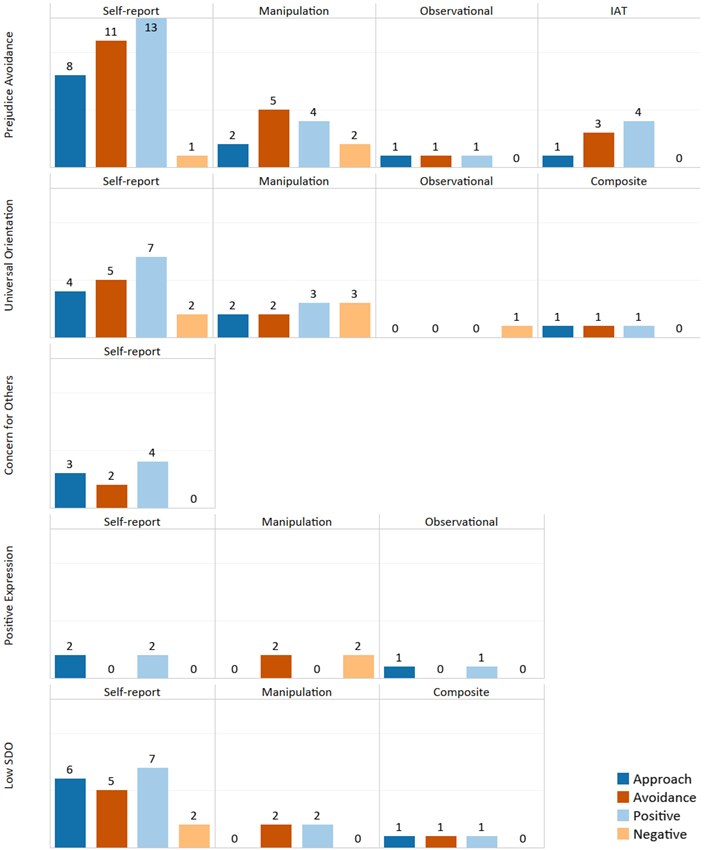

Appendix A. Approach, Avoidant, Positive and Negative Outcomes by Domain

References

- Crandall, C.S., Eshleman, A. A justification-suppression model of the expression and experience of prejudice. Psychol Bull 2003, 129(3), 414-46. PMID: 12784937. [CrossRef]

- Falomir-Pichastor, J. M., Mugny, G., Frederic, N., Berent, J., & Lalot, F. Motivation to maintain a nonprejudiced identity: The moderating role of normative context and justification for prejudice on moral licensing. Social Psychology 2018, 49(3), 168–181. [CrossRef]

- Project Implicit. Available online: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html.

- “Most Americans Say Trump’s Election Has Led to Worse Race Relations in the U.S.” Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (2017). https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/12/19/most-americans-say-trumps-election-has-led-to-worse-race-relations-in-the-u-s/.

- “Race in America 2019.” Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (2019). https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/04/09/race-in-america-2019/.

- “For Women’s History Month, a look at gender gains – and gaps – in the U.S.” Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (2024). https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/02/27/for-womens-history-month-a-look-at-gender-gains-and-gaps-in-the-us/.

- “2023 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People.” The Trevor Project, United States (2023). https://www.thetrevorproject.org/.

- Warren, M. A., Warren, M. T., Bock, H., & Smith, B. “If you want to be an ally, what is stopping you?” Mapping the landscape of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and contextual barriers to allyship in the workplace using ecological systems theory. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1998, 75(3), 811–832. [CrossRef]

- Warren, M. A., Sekhon, T., Winkelman, K. M., & Waldrop, R. J. Should I “check my emotions at the door” or express how I feel? Role of emotion regulation versus expression of male leaders speaking out against sexism in the workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2022, 52(7), 547–558. [CrossRef]

- Roemer, J.E. Theories of Distributive Justice. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1996.

- Wolff, J. Fairness, respect and the egalitarian ethos revisited. Journal of Ethics 2010, 14, 335-350. [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E., Bernhard, H., Rockenbach, B. Egalitarianism in young children. Nature 2008, 454, 1079-83. [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, G. B., Gollwitzer, P. M., Wasel, W., & Schaal, B. Preconscious control of stereotype activation through chronic egalitarian goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1999, 77(1), 167–184. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, R. W., & Drwecki, B. B. Why Are Some Individuals Not Racially Biased?: Susceptibility to Affective Conditioning Predicts Nonprejudice Toward Blacks. Psychological Science 2007, 18(9), 816-823. [CrossRef]

- Brigham, J. C. College students’ racial attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 1993, 23, 1933–1967. [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1998, 74(6), 1464–1480. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, W. B., Gray, H. M., Mendoza-Denton, R., Major, B., & Epel, E. S. Why egalitarianism might be good for your health: Physiological thriving during stressful intergroup encounters. Psychological Science 2007, 18(11), 991–998. [CrossRef]

- Amodio, D. M., Devine, P. G., & Harmon-Jones, E. Individual differences in the regulation of intergroup bias: The role of conflict monitoring and neural signals for control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2008, 94(1), 60–74. [CrossRef]

- Castelli, L., Tomelleri, S. Contextual effects on prejudiced attitudes: When the presence of others leads to more egalitarian responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2008, 44(3), 679-686. [CrossRef]

- Johns, M., Cullum, J., Smith, T., & Freng, S. Internal motivation to respond without prejudice and automatic egalitarian goal activation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2008, 44(6), 1514–1519. [CrossRef]

- Van Lange, P. A. M. The pursuit of joint outcomes and equality in outcomes: An integrative model of social value orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1999, 77(2), 337–349. [CrossRef]

- Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. The active control of prejudice: Unpacking the intentions guiding control efforts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2009, 96(3), 640–652. [CrossRef]

- Wellman, J. A., Czopp, A. M., & Geers, A. L. The egalitarian optimist and the confrontation of prejudice. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2009, 4(5), 389–395. [CrossRef]

- Winslow, M. P., Aaron, A., & Amadife, E. N. African Americans’ lay theories about the detection of prejudice and nonprejudice. Journal of Black Studies 2011, 42(1), 43–70. [CrossRef]

- Legault, L., & Green-Demers, I. The protective role of self-determined prejudice regulation in the relationship between intergroup threat and prejudice. Motivation and Emotion 2012, 36(2), 143–158. [CrossRef]

- Legault L, Green-Demers I, Grant P, Chung J. On the self-regulation of implicit and explicit prejudice: a self -determination theory perspective. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2007, 33(5), 732-49. [CrossRef]

- Schmader, T., Croft, A., Scarnier, M., Lickel, B., & Mendes, W. B. Implicit and explicit emotional reactions to witnessing prejudice. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2012, 15(3), 379–392. [CrossRef]

- Skorinko, J. L. M., Lun, J., Sinclair, S., Marotta, S. A., Calanchini, J., & Paris, M. H. Reducing prejudice across cultures via social tuning. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2015, 6(4), 363–372. [CrossRef]

- Aranda, M., & Montes-Berges, B. How to avoid stereotypes? Evaluation of a strategy based on self-regulatory processes. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 2016, 19. [CrossRef]

- Gabarrot, F., & Falomir-Pichastor, J. M. Ingroup identification increases differentiation in response to egalitarian ingroup norm under distinctiveness threat. International Review of Social Psychology 2017, 30(1), 219-228. [CrossRef]

- LaCosse, J., & Plant, E. A. Internal motivation to respond without prejudice fosters respectful responses in interracial interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2020, 119(5), 1037–1056. [CrossRef]

- Szekeres, H., Halperin, E., Kende, A., & Saguy, T. The aversive bystander effect whereby egalitarian bystanders overestimate the confrontation of prejudice. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 10538. [CrossRef]

- Najdowski, C. J., Wilcox, S. A., Brace, J. K., & Anderson, M. An exploratory study of anti-Black racism in social media behavior intentions: Effects of political orientation and motivation to control prejudice. Translational Issues in Psychological Science 2024. [CrossRef]

- Estevan-Reina, L., de Lemus , S., Megías , J. L., Radke , H. R. M., Becker, J. C., & McGarty, C. How do disadvantaged groups perceive allies? Women’s perceptions of men who confront sexism in an egalitarian or paternalistic way. European Journal of Social Psychology 2024, 54, 892-910. [CrossRef]

- Beere, C. A., King, D. W., Beere, D. B., & King, L. A. The Sex-Role Egalitarianism Scale: A measure of attitudes toward equality between the sexes. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 1984, 10(7-8), 563–576. [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, S. L., Rust, M. C., Dovidio, J. F., Bachman, B. A., & Anastasio, P. A. The Contact Hypothesis: The Role of a Common Ingroup Identity on Reducing Intergroup Bias. Small Group Research 1994, 25(2), 224-249. [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, S. L., Rust, M. C., Dovidio, J. F., Bachman, B. A., et al. The contact hypothesis: The role of a common ingroup identity on reducing intergroup bias among majority and minority group members. In What’s social about social cognition? Research on socially shared cognition in small groups, Nye, J. L., Brower, A.M., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc., 1996; pp. 230-260. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S. T., & Ziller, R. C. Toward a theory and measure of the nature of nonprejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1997, 72(2), 420–434. [CrossRef]

- Monteith, M. J., & Walters, G. L. Egalitarianism, moral obligation, and prejudice-related personal standards. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 1998, 24(2), 186–199. [CrossRef]

- Katz, I., & Hass, R. G. Racial ambivalence and American value conflict: Correlational and priming studies of dual cognitive structures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 55(6), 893–905. [CrossRef]

- Dall’Ara, E., & Maass, A. Studying sexual harassment in the laboratory: Are egalitarian women at higher risk? Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 1999, 41(9-10), 681–704. [CrossRef]

- Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. Aversive racism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; M. P. Zanna, Ed., Elsevier Academic Press, 2004; Volume 36, pp. 1–52). [CrossRef]

- Chandler, C., Brooks, J., Mulvaney, R., & Derryberry, P. Addressing the relationships among moral judgment development, authenticity, nonprejudice, and volunteerism. Ethics and Behavior 2009, 19(3), 201-217. 10.1080/10508420902886650.

- Wyer, N. A. Salient egalitarian norms moderate activation of out-group approach and avoidance. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2010, 13(2), 151-165. [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L. A., Mescher, K., & Moss-Racusin, C. A. Reactions to gender egalitarian men: Perceived feminization due to stigma-by-association. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2013, 16(5), 572-599. [CrossRef]

- Lyness, K. S., & Judiesch, M. K. Gender egalitarianism and work–life balance for managers: Multisource perspectives in 36 countries. Applied Psychology: An International Review 2014, 63(1), 96–129. [CrossRef]

- Pahlke, E., Bigler, R. S., & Martin, C. L. Can fostering children’s ability to challenge sexism improve critical analysis, internalization, and enactment of inclusive, egalitarian peer relationships? Journal of Social Issues 2014, 70(1), 115–133. [CrossRef]

- Falomir-Pichastor, J. M., Mugny, G., & Berent, J. The side effect of egalitarian norms: Reactive group distinctiveness, biological essentialism, and sexual prejudice. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2017, 20(4), 540–558. [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, M., Jacoby-Senghor, D. S., & Brown, N. D. Detecting Prejudice From Egalitarianism: Why Black Americans Don’t Trust White Egalitarians’ Claims. Psychological Science 2022, 33(6), 889-905. [CrossRef]

- McConahay, J. B. Modern racism, ambivalence, and the Modern Racism Scale. In Prejudice, Discrimination, And Racism, Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., Eds.; Academic Press, 2007, (pp. 91–125).

- Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. Aversive racism and selection decisions: 1989 and 1999. Psychological Science 2000, 11(4), 315–319. [CrossRef]

- Fietzer, A. W., & Ponterotto, J. A Psychometric Review of Instruments for Social Justice and Advocacy Attitudes. Journal for Social Action in Counseling & Psychology 2015, 7(1), 19–40. [CrossRef]

- Patel, V. S. Moving Toward an Inclusive Model of Allyship for Racial Justice. The Vermont Connection 2011, 32(1). https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/tvc/vol32/iss1/9.

- Winnifred, R. L., Thomas, E., Chapman, C.M., Achia, T., Wibisono, S., Mirnajafi, Z., & Droogendyk L. Emerging research on intergroup prosociality: Group members’ charitable giving, positive contact, allyship, and solidarity with others. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2019, 13(3). [CrossRef]

- Radke, H. R. M., Kutlaca, M., Siem, B., Wright, S. C., & Becker, J. C. Beyond Allyship: Motivations for Advantaged Group Members to Engage in Action for Disadvantaged Groups. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2020, 24(4), 291-315. [CrossRef]

- Monteith, M. J., & Spicer, C. V. Contents and correlates of Whites’ and Blacks’ racial attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2020, 36(2), 125–154. [CrossRef]

- Schwab, A. K., & Greitemeyer, T. Failing to establish evaluative conditioning effects for indirect intergroup contact on Facebook. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 2015, 37(2), 87–104. [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Gold, R., & Tran, A. G. T. T. Socialization and well-being in multiracial individuals: A moderated mediation model of racial ambiguity and identity. Journal of Counseling Psychology 2018, 65(4), 413–422. [CrossRef]

- Aberson, C. L., & Ettlin, T. E. The Aversive Racism Paradigm and Responses Favoring African Americans: Meta-Analytic Evidence of Two Types of Favoritism. Social Justice Research 2004, 17(1), 25–46. [CrossRef]

- Plant, E. A., Devine, P. G., & Peruche, M. B. Routes to positive interracial interactions: Approaching egalitarianism or avoiding prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2010, 36(9), 1135–1147. [CrossRef]

- Harber, K. D., Stafford, R., & Kennedy, K. A. The positive feedback bias as a response to self-image threat. British Journal of Social Psychology 2010, 49(1), 207–218. [CrossRef]

- Mann, N. H., & Kawakami, K. The long, steep path to equality: Progressing on egalitarian goals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 2012, 141, 187–197. [CrossRef]

- van Bergen, D. D., de Ruyter, D. J., & Pels, T. V. M. “Us against them” or “all humans are equal”: Intergroup attitudes and perceived parental socialization of Muslim immigrant and native Dutch youth. Journal of Adolescent Research 2017, 32(5), 559–584. [CrossRef]

- Saguy, T., Tausch, N., Dovidio, J.F., & Pratto, F. The irony of harmony: intergroup contact can produce false expectations for equality. Psychol Sci. 2009, 20(1), 114-21. [CrossRef]

- Does, S., Derks, B., Ellemers, N., & Scheepers, D. At the heart of egalitarianism: How morality framing shapes cardiovascular challenge versus threat in whites. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2012, 3(6), 747–753. [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.K., Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Pratto, F., Henkel, K.E., Foels, R., & Stewart, A.L. The nature of social dominance orientation: Theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO₇ scale. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015, 109(6), 1003-28. [CrossRef]

- Ho, A. K., Kteily, N. S., & Chen, J. M. “You’re one of us”: Black Americans’ use of hypodescent and its association with egalitarianism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2017, 113(5), 753–768. [CrossRef]

- Kteily, N. S., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., & Ho, A. K. Hierarchy in the eye of the beholder: (Anti-)egalitarianism shapes perceived levels of social inequality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2017, 112(1), 136–159. [CrossRef]

- Yogeeswaran, K., Davies, T., & Sibley, C. G. Janus-faced nature of colorblindness: Social dominance orientation moderates the relationship between colorblindness and outgroup attitudes. European Journal of Social Psychology 2017, 47(4), 509–516. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, N. K., Milojev, P., Barlow, F. K., & Sibley, C. G. Ingroup friendship and political mobilization among the disadvantaged. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology 2015, 21(3), 358–368. [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression; Cambridge University Press, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Kende, J., Phalet, K., Van den Noortgate, W., Kara, A., & Fischer, R. Equality revisited: A cultural meta-analysis of intergroup contact and prejudice. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2018, 9(8), 887–895. [CrossRef]

- Lucas, B. J., & Kteily, N. S. (Anti-)egalitarianism differentially predicts empathy for members of advantaged versus disadvantaged groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2018, 114(5), 665–692. [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F., Saguy, T., Stewart, A. L., Morselli, D., Foels, R., Aiello, A., Aranda, M., Cidam, A., Chryssochoou, X., Durrheim, K., Eicher, V., Licata, L., Liu, J. H., Liu, L., Meyer, I., Muldoon, O., Papastamou, S., Petrovic, N., Prati, F., … Sweetman, J. Attitudes Toward Arab Ascendance: Israeli and Global Perspectives. Psychological Science 2014, 25(1), 85-94. [CrossRef]

- Çoksan , S. & Cingöz-Ulu, B. Group norms moderate the effect of identification on ingroup bias. Current Psychology 2022, 4, 64-75. [CrossRef]

- Do Bú, E. A., Madeira, F., Pereira, C. R., Hagiwara, N., & Vala, J. Intergroup time bias and aversive racism in the medical context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2023, Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, C., Lundberg, K. B., Lauber, M., Wallace, H., & Marston, A. When coupled with anti-ealitarianism, colour evasion predicts protection of the status quo during university-wide movement for racial justice. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 2023, 33(4), 1211-1224. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist 1997, 52(12), 1280–1300. [CrossRef]

- Apfelbaum, E. P., Stephens, N. M., & Reagans, R. E. Beyond one-size-fits-all: Tailoring diversity approaches to the representation of social groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2016, 111(4), 547–566. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A. R., Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. The nature of contemporary prejudice: Insights from aversive racism. Social and personality psychology Compass 2009, 3(3), 314-338. [CrossRef]

- Sue, D. W. Microaggressions and Marginality: Manifestation, Dynamics, and Impact. John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- Tropp, L. R., & Mallett, R. K. Moving Beyond Prejudice Reduction: Pathways to Positive Intergroup Relations; American Psychological Association, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Urbiola, A., McGarty, C., & Costa-Lopes, R. The AMIGAS Model: Reconciling Prejudice Reduction and Collective Action Approaches Through a Multicultural Commitment in Intergroup Relations. Review of General Psychology 2022, 26(1), 68-85. [CrossRef]

- Mirels, H. L., & Garrett, J. B. The Protestant Ethic as a personality variable. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1971, 36(1), 40–44. [CrossRef]

- Krysan, M., & Moberg, S. A portrait of African American and White racial attitudes. Institute of Government Affairs 2016. https://igpa.uillinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Krysan-Moberg-September-9-2016-1.pdf.

- Kunstman, J. W., Tuscherer, T., Trawalter, S., & Lloyd, E. P. What lies beneath? Minority group members’ suspicion of Whites’ egalitarian motivation predicts responses to Whites’ smiles. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2016, 42(9), 1193–1205. [CrossRef]

- Major, B., Kunstman, J. W., Malta, B. D., Sawyer, P. J., Townsend, S. M., % Mendes, W. B. Suspicion of motives predicts minorities’ responses to positive feedback in interracial interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2016, 62, 75-88. [CrossRef]

- Warren, M. A. & Warren, M. T. The EThIC model of virtue-based allyship development: A new approach to equity and inclusion in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics 2021. [CrossRef]

| Author | Sample | Measure | Outcome | Moderator |

| Plant & Devine (1998) [9] | N = 1,743 U.S. college students | Scale development: Internal Motivation to Respond without Prejudice (IMS), External Motivation to Respond without Prejudice (EMS) |

Internal: (+ correlated) pro-Black attitudes, Attitudes Toward Blacks (ATB), Humanitarianism/Egalitarianism (H/E), (- correlated) modern racism, anti-Black attitudes, Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA), Protestant Work Ethic (PWE); guilt, shame, and self-criticism; External: (+) Modern Racism, Right-Wing Authoritarianism, social evaluation, (-) ATB, threat. |

N/A |

| Moskowitz, et al. (1999) [14] | N = 242 German male students | Manipulation: Participants forced to respond stereotypically about women on a fixed-survey. Less stereotypical follow-up responses denoted egalitarianism | Lower subsequent stereotype scores were related to the inhibition of implicit stereotype activation. | N/A |

| Livingston & Drwecki (2007) [15] | N = 208 White American students | ATB [16], the Implicit Association Test (IAT)[17] | Low bias scores were associated with lower susceptibility to negative affect and more susceptibility to positive affect. | N/A |

| Mendes et al., (2007) [18] | N = 78 U.S. White adults | IAT [17] | Lower implicit racial bias scores were correlated with lower threat appraisals, less anxiety, and higher salutary neuroendocrine products when being interviewed by a Black research confederate | N/A |

| Amodio et al., (2008) [19] |

N = 73 White U.S. students | IMS, EMS [9] ATB [16] | High IMS was related to positive explicit attitudes toward Black people but only high IMS/low EMS was related to better stereotype inhibition on implicit tasks compared to high IMS and high EMS; High IMS/low EMS showed better conflict monitoring activity. | EMS moderated the extent to which highly IMS successfully inhibited stereotype activation. |

| Castelli & Tomelleri (2008) [20] |

N = 452 Italian students | IAT [17] self-reported perceptions of discriminatory norms | IAT responses were correlated with lower acceptability of discriminatory norms and quicker access to egalitarian words on a lexical decision task following a Black prime | The presence of others facilitated lower implicit bias and quicker egalitarian concept access compared to being alone |

| Johns et al., (2008) [21] | N = 164 White U.S. students | IMS, EMS [9], ring measure of social values (RSV) for egalitarian goal activation [22] | Participants with high IMS displayed more egalitarian giving in a points allocation task. In a subsequent task, high IMS predicted less stereotype activation on a lexical decision measure, mediated by egalitarian goal activation (RSV task). | IMS, Black prime |

| Plant & Devine (2009) [23] | N = 431 White U.S. students (across 3 studies) | IMS, EMS [9] | High EMS predicted amount of time spent decreasing detectable prejudice whereas high IMS and EMS predicted amount of time spent decreasing detectable and undetectable prejudice. | Feedback about possessing bias influenced high IMS, low EMS to reduce undetectable prejudice. |

| Wellman et al., (2009) [24] | N = 57 White American college students | ATB [16] | Confronting a racist joke | Witnessing a prior confrontation (exemplar); optimism |

| Winslow et al., (2011) [25] | N = 236 Black students | Open-ended prompt: “What are some things that you have personally seen or heard a white person do or say that made you think that person was not prejudiced?” and “In general, what can white people do to let you know they are not prejudiced, if they really are not?” | Smiling, greeting, or helping (24.5%), equal treatment (10.8%), confronting prejudice in others (10.8%), actively seek interactions (4.7%) and relationships (5.3%) with minorities; Avoid racist statements (17.6%), behave in authentic behaviors/just “be yourself” and do not overcompensate (69.1%), treat people equally (17.7%) | N/A |

| Legault & Green-Demers (2012) [26] | N = 377 Canadian students | Motivation to be Nonprejudiced scale (MNPS) [27]; IAT [17] | Self-determined prejudice regulators showed less modern racism, negative affect, interracial anxiety, implicit bias, and discrimination, and more positive affect | N/A |

| Schmader et al., (2012) [28] | N = 143 White American college students | IMS, EMS [9] | IMS (not EMS) predicted negative emotional reaction towards anti-diversity viewpoints and physiological threat reactivity towards anti-diversity viewpoints. | When a Black confederate was present and appeared angry, IMS predicted slightly more negative emotion. |

| Skorinko et al., (2015) [29] | N = 307 college students in America and Hong Kong |

Manipulation: experimenter wore a t-shirt that read “People don’t discriminate, they learn it.” | Egalitarian prime exposure led to lower implicit and explicit bias toward homosexual targets in the collectivistic conditions | Cultural background: Collectivistic conditions led to positive outcomes whereas individualistic conditions had no effect. |

| Aranda & Montes-Berges (2016) [30] | N = 474 Spanish students | Manipulation: Text highlighting global gender inequality. Self-report: 30 -item scale of Prejudice, Egalitarian Commitment, Awareness of Inequality |

In a decision-making task where participants assigned male and female targets to differing roles, female targets were assigned to more mid- and high-level positions. | Less stereotypical role-placement was observed more in stereotypically feminine companies; Women displayed less stereotypical role-placement |

| Gabarrot & Falomir-Pichastor (2017) [31] |

N = 82 French college students | Manipulation: Information conveyed that majority of ingroup did not consider favoring ingroup against outgroup in terms of social welfare, housing, or education benefits, to be legitimate. |

Higher identification with an ingroup predicted more prejudice toward the outgroup and negatively predicted stereotyping. | When high group similarity was primed with egalitarian norms, participants were more prejudiced. |

| Falomir-Pichastor et al., (2018) [2] |

N = 506 Swiss college students | Manipulation: see Gabarrot and Falomir-Pichastor (2017) [31] |

High prejudice justification predicted a preference for ingroup and high prejudice against the outgroup. | Within the egalitarian norm condition, ingroup preference and prejudice was higher among high prejudice justifiers if participants engaged in prior egalitarian behaviors than when they had not. |

| LaCosse & Plant (2020) [32] | Study 1: N = 99 Black undergraduate students Studies 2 – 6: Total N = 553 White undergraduate students and MTurk workers | Study 1: open-ended prompt “In general, when interacting with White people, what actions, behaviors, topics of conversation, etc., do they perform that lead you to feel respected?” Studies 2-6: self-reported intentions to show respect, avoid prejudice, focus on self/partner, IMS, EMS, memory recall (Study 5 only), observed engagement (Study 6 only) |

Study 1: nonprejudiced and unbiased behaviors (incl active acknowledgement of social justice), rejecting stereotypes, genuine engagement. Study 2 – 6: IMS predicted intentions to show respect, focus on self and partner, avoid prejudice, and engage; better memory recall of partner; more engagement behaviors (EMS predicted prejudice concerns and self-focused intentions) |

IMS and EMS |

| Szekeres et al. (2023) [33] | N = 1,116 (across 3 studies) ranging from Black, Muslim, and Latinx Americans, and Romanian and Hungarian adults | IMS [9] | Participants with stronger egalitarian values were more likely to hypothetically confront bias than lower value counterparts. However, egalitarians were less likely to actually confront bias, compared to their predictions. | Participants higher in behavioral uncertainty were even less likely to confront. |

| Najdowski et al. (2024) [34] | N = 108 non-Black U.S. adults | IMS [9] | Higher internal motivations were related to reduced likelihood of promoting anti-Black social media post compared to egalitarian post. | N/A |

| Estevan-Reina et al. (2024) [35] | N = 1,010 women (across 4 studies) | Manipulation of a man confronting sexism using egalitarian claims | Women found men who confronted sexism with egalitarian language, compared to paternalistic language, as better allies, felt more empowered, and perceived less of a power differential between themselves and the male ally. | N/A |

| Author | Sample | Measure | Outcome | Moderator |

| Beere et al., (1984) [36] | N = 367 adults | Scale development: sex-role Egalitarianism Scale | Women scored higher than men, psychology students scored higher than business students, students scored higher than police officers and senior citizens. | N/A |

| Gaertner et al. (1994) [37] | N = 1,357 high school students | Self-reported perceptions of equal status, cooperative interdependence, association and interaction, and supportive norms | Egalitarian social norms were negatively correlated with emotional bias and negative attitudes toward racial outgroup members. | N/A |

| Gaertner et al., (1996) [38] | Study 3: N = 229 U.S. adults | Self-reported perceptions of equal status, cooperative interdependence, association and interaction, and supportive norms | Positive contact conditions were related to less social anxiety and lower sociability bias. | N/A |

| Phillips & Ziller (1997) [39] | N = 664 | Scale development: Universal Orientation scale | (+) pro-Black attitudes, HE, PWE, (-) modern racism, anti-Black attitudes | N/A |

| Monteith & Walters (1998) [40] | N = 244 non-Black students | Self-report items that measured HE and PWE [41] | Among high prejudiced, HE led to moral obligation to regulate prejudice whereas PWE did not | Individual difference in perceptions of attainment of egalitarianism moderated prejudice regulation |

| Dall’Ara & Maass (1999) [42] | N = 120 Italian male students | Manipulation: female target described as occupying a nontraditional role who was not afraid to compete with a man and pursued equal work rights | Men were more likely to sexually harass (sent a pornographic image) and needed fewer persuasion attempts to sexually harass egalitarian targets compared to traditional targets. | Higher scores on measures of sexism, masculine identity, and likelihood to sexually harass |

| Dovidio & Gaertner (2004) [43] | Review | Combination of self-report and observational | Self-reported egalitarians engaged in fewer emergency and non-emergency helping behaviors, less support for affirmative action, greater perceptions of guilt among Black vs. White criminals, discriminatory hiring practices if they could justify their behavior on some aspect of the environment. | Environment ambiguity/justification |

| Derryberry et al., (2009) [44] | N = 124 U.S. students | Universal Orientation Scale [39] | Higher scores predicted higher value, understanding, and career-based motivations to engage in volunteer behaviors. | N/A |

| Wyer (2010) [45] | N = 100 students | Manipulation: five-minute essay response to “All people are equal; therefore, they should be treated the same way” | Egalitarian prompt (compared to control) inhibited activation of avoidant words among high in prejudice | N/A |

| Rudman, Mescher & Moss-Racusin (2012) [46] | N = 518 | Manipulation: male target described as supporting women’s rights, enjoying women’s studies, or having been involved in women’s issues research | Explicit and implicit favoring of egalitarian target (compared to sexist target) but was rated as more feminine, more gay, less masculine | Women showed more favorability of egalitarian target than men. |

| Lyness & Judiesch (2014) [47] | N = 40,921 individuals and 36 countries | Gender Inequality Index, Gender Egalitarian Practices, Gender Egalitarian values | Women and men report no difference in work-life balance in high gender egalitarian countries compared to low; Supervisors relied less on stereotypes when appraising women’s work-life conflict in high gender egalitarian countries compared to low. | N/A |

| Pahlke et al., (2014) [48] | N = 137 U.S. elementary students | Manipulation: five, 30-minute gender pro-egalitarian lessons in identifying, analyzing, responding to gender stereotyping, biased judgements, unequal gender relationships; Self-report egalitarian attitudes (Preschool Occupation, Activity, and Trait-Attitude Measure) | Gender egalitarian lessons increased ability to identify sexism in the media and provide antisexist challenges in response to sexist remarks compared to control lessons. | N/A |

| Falomir-Pichastor et al., (2017) [49] | N = 521 adults (across 2 studies) | Manipulation: newspaper article about social equality stating “In sum, we are all equal and all groups should be equally treated” with statistics that 90% of Americans agree | Men reported more psychological differences between gay and straight men following egalitarian norms, negative attitudes toward gay people. | Promotion of biological similarities between groups; women did not show this pattern |

| Rosenblum et al., 2022 [50] |

N = 1,515 White and Black U.S. adults across 3 studies |

Modern Racism Scale [51], IMS [9], Open-ended response: “Do you believe all people are equal and should have equality of opportunity?” | Black perceivers accurately detected White racial attitudes and motivations from egalitarian writing prompts.Humanizing language and support for equal opportunity were more indicative of lower prejudice and internal motivations. | N/A |

| Author | Sample | Measure | Outcome | Moderator |

| Katz & Hass (1988) [41] | N = 202 U.S. White students | Scale development: Humanitarianism-Egalitarianism (HE) scale | (+) pro-Black attitudes, (-) anti-Black attitudes | N/A |

| Monteith & Spicer (2000) [57] | N = 496 White and 275 Black students | Open-ended essay response to “I have generally positive/negative feelings toward Black/White people because…” | White participants: HE (+) with more positive essay themes and negatively correlated with modern racism; Black participants: No correlation between value orientation and essay themes |

Racial Identity |

| Schwab & Greitemeyer (2015) [58] | N = 357 adults from 18 countries | HE [41], self-reported outgroup attitudes | HE (+) with number of outgroup friends on social media and positive outgroup attitudes | N/A |

| Villegas-Gold & Tran (2018) [59] | N = 383 multiracial U.S. adults | Self-report egalitarian socialization scale | (+) with integrated identification, well-being, and self-esteem | Higher racial ambiguity was associated with more egalitarian socialization and more positive outcomes. |

| Author | Sample | Measure | Outcome | Moderator |

| Aberson & Ettlin (2004) [60] | N = 31 studies (meta-analysis) | Coded articles for egalitarian contexts and norms | Within clear egalitarian contexts, Black targets were favored; within ambiguous contexts, AA targets received more negative ratings and behaviors. | N/A |

| Plant et al., (2010) [61] | N = 230 non-Black U.S. students | IMS [9] | High IMS more likely than low IMS to report focusing on approach goals/strategies for upcoming interracial interaction and more likely to use these strategies during a real interracial interaction (resulting in more pleasant interaction). | Among high internally motivated P’s, high external motivation (EMS) reduced positive interaction quality. |

| Harber et al., (2010) [62] | N = 108 White U.S. student teachers | Manipulation: Results of a “social issues survey” that conveyed either a pro- or anti-minority slant; Participants had to provide five examples of famous Black individuals from easy or difficult categories (government vs. math). |

When egalitarian self-images were threatened, teachers gave more positive essay feedback, recommended less time for developing writing skills, and supplied more positive comments to students they thought were Black compared to students they thought were White, regardless of student writing ability. | N/A |

| Mann & Kawakami (2012) [63] | N = 225 students | Manipulation: instructed to “try to have positive evaluations when a Black target appeared on screen” which would be monitored by a progress bar that showed they made progress toward or away from this goal. | Progressing on egalitarian goals (+) with sitting further away from the Black research confederate, closer to the White research confederate, and greater implicit bias. | N/A |

| Van Bergen et al., (2017) [64] | N = 22 Turkish, Moroccan, or Dutch youth | Interviews of youth on attitudes toward outgroup members, experiences with disparate treatment, and parents’ responses to these events | Youth with positive outgroup attitudes reported that their parents had multicultural friend groups, taught about fallacies of stereotypes, and encouraged positive intergroup interactions (parent-child similarity). | N/A |

| Author | Sample | Measure | Outcome | Moderator |

| Saguy et al., (2009) (only study 2) [65] | N = 175 Israeli citizens | Questionnaire about contact, attention to illegitimate aspects of inequality (‘‘To what extent would you consider the inequality between the groups as just?’’), outgroup fairness, and support for social change. | Positive contact between advantaged and disadvantaged groups increased disadvantaged members’ positive attitudes toward the outgroup, which in turn increased perceptions of the outgroup as fair, decreased attention to inequality, and decreased support for social change. | N/A |

| Does et al., (2012) [66] | N = 37 Dutch college students | Behavior manipulation task: participants asked to give oral presentation via webcam about equality in terms of ideals or obligations and how they could attain the ideal or obligation of social equality. | Speech tasks given from an ideal perspective elicited greater relative challenge than the obligation perspective. Behaviorally, obligation-framed speeches were spoken more slowly than ideal-framed speeches, indicative of self-monitoring. | Regulatory focus |

| Ho et al., (2015) [67] | N = 3,107 American adults recruited from various online platforms | Scale development: subdomain (SDO egalitarianism) of social dominance orientation | (+)system legitimacy beliefs, political conservatism, support for unequal intergroup distribution of resources, opposition to hierarchy attenuating social policies; (-) concern for harm and fairness. | Higher status groups (men and White people) had higher levels of social dominance beliefs. |

| Ho et al., (2017) [68] | N = 2,731 American adults recruited from various online platforms | Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) [67] | Both Black and White participants categorized biracial targets as more Black than White (hypodescent) but this was moderated by SDO only among White participants. Black participants use of hypodescent was negatively correlated with SDO and mediated by perceptions of discrimination against biracial people and sense of shared fate. | White hypodescent derivative of high SDO whereas Black hypodescent is derivative of perceived discrimination and shared fate. |

| Kteily et al., (2017) [69] | N = 1,221 American adults recruited from various online platforms (3 of 5 studies included) | SDO [67] | SDO (-) perceptions of power differences between groups, which predicted support for egalitarian social policy. Incentivization to report honestly had no effect on the relationship between SDO and perceptions of lessened inequality, indicating differences in actual perceptions of inequality not just motivations. | N/A |

| Yogeeswaran et al., (2017) [70] | N =4,599 New Zealand adults | SDO [71,72] | Low SDO: colorblindness negatively predicted outgroup warmth | SDO moderates the effects of colorblindness. |

| Kende et al., (2018) [73] | N = 459 studies including 660 samples in 36 countries | Schwartz Value Surveys (SVS): “How important is equality (equal opportunity for all) as a guiding principle in your life?”; GNI (index of inequality) | The negative correlation between intergroup contact and prejudice was stronger in countries with higher cultural egalitarianism, above and beyond equal status situational factors. This link was weaker in countries with stronger hierarchy-enforcing culture. Thus, cultural and situational equality produce most optimal outcomes for intergroup contact and prejudice reduction. | N/A |

| Lucas & Kteily (2018) [74] | N = 2,340 | SDO [60,75,80] | Increased empathy with disadvantaged targets compared to advantaged targets. When the target was disadvantaged, SDO (-) empathy; when the target was advantaged, SDO (+) empathy. High SDO (-) perceptions of harm against disadvantaged targets and subsequently predicted low levels of empathy. Among advantaged targets, SDO (+) perceived harm and high levels of empathy. (-) between SDO and empathy among disadvantaged targets was stronger than the (+) between SDO and empathy among advantaged targets. |

Degree to which high SDO individuals felt empathy, perceived harm, or opposed detrimental policies depended on whether or not the target was in an advantaged or disadvantaged group. |

| Coksan & Cingoz-Ulu (2022) [76] | N = 146 Kurdish and Turkish participants | Self-report on ingroup norms | When group members perceive ingroup norms as egalitarian, social identity has no effect on ingroup bias and resource allocation. | N/A |

| Do Bu et al. (2023) [77] | N = 617 White, Portuguese medical trainees (across 5 studies) | SDO [60] | Medical professionals who hold egalitarian values still spent less time assessing and diagnosing Black patients compared to White patients, resulting in lower diagnostic accuracy, reduced pain perception accuracy, and increase opioid prescription behaviors. | Egalitarians with higher implicit bias engaged in this “aversive racism” behavior. |

| Hoyt et al. (2023) [78] | N = 255 undergraduate American students | SDO [60] | Anti-egalitarians, but not egalitarians, who scored higher in color evasiveness (or colorblindness) indicated less support for Black student activism, reduced engagement in social justice, lower satisfaction with student leaders, lower perceived effectiveness of demonstrations, and higher beliefs in activism as causing intergroup conflict. | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).