Submitted:

02 July 2024

Posted:

03 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Plant Material

2.2. Soil Sampling, Analyses and Measurements

2.4. Pyrolysis-Field Ionization Mass Spectrometry (Py-FIMS)

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Site Characteristics

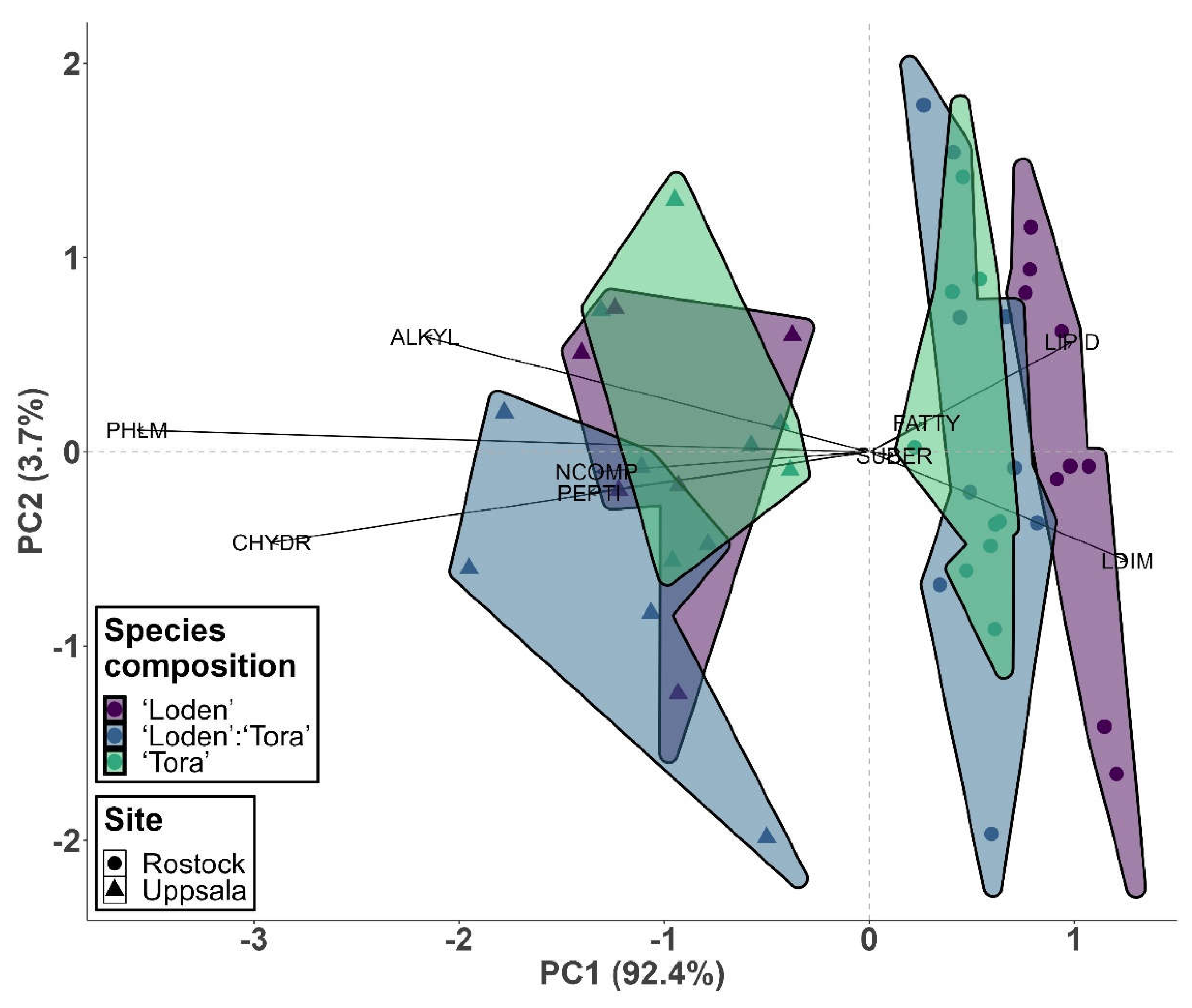

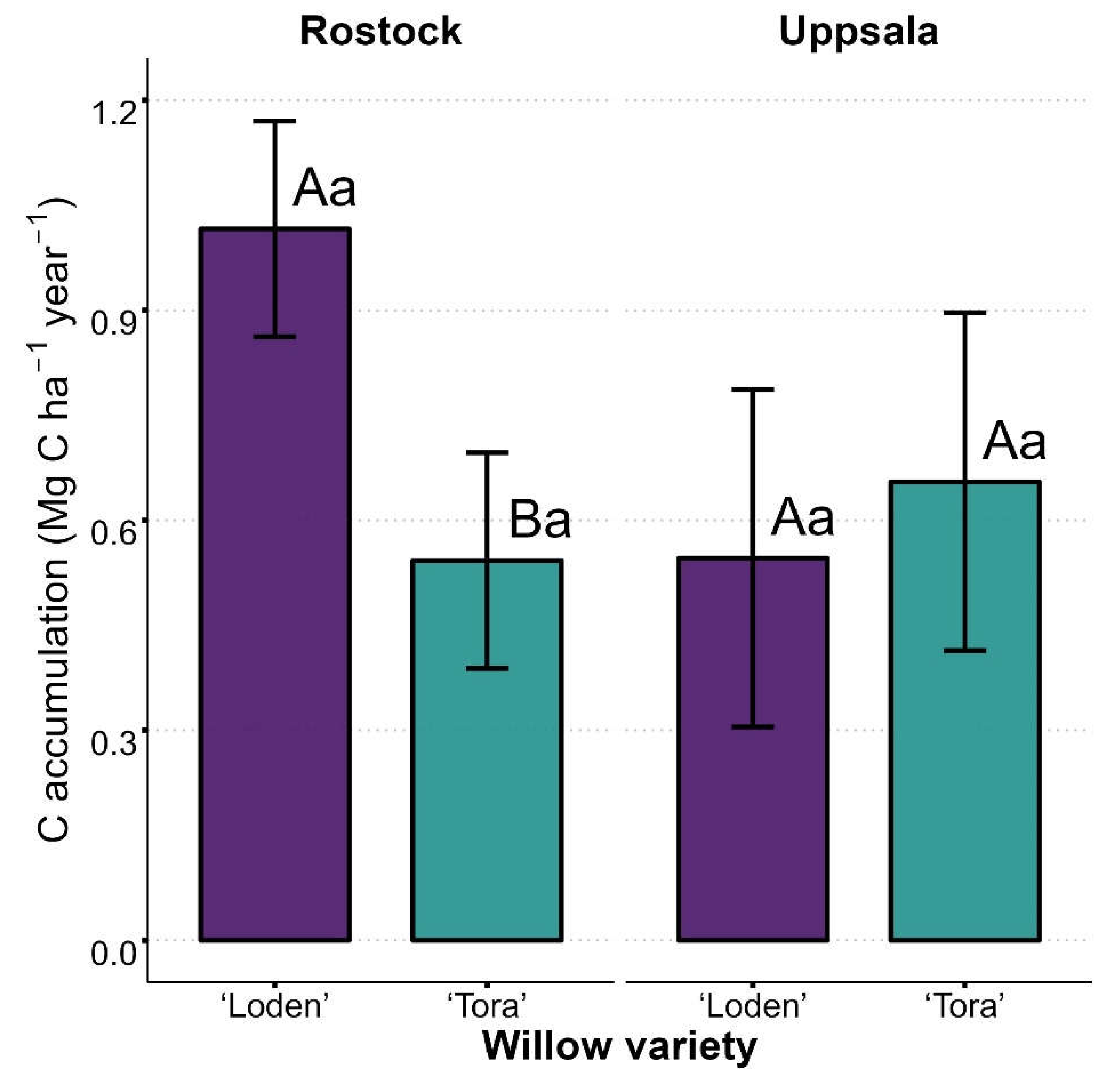

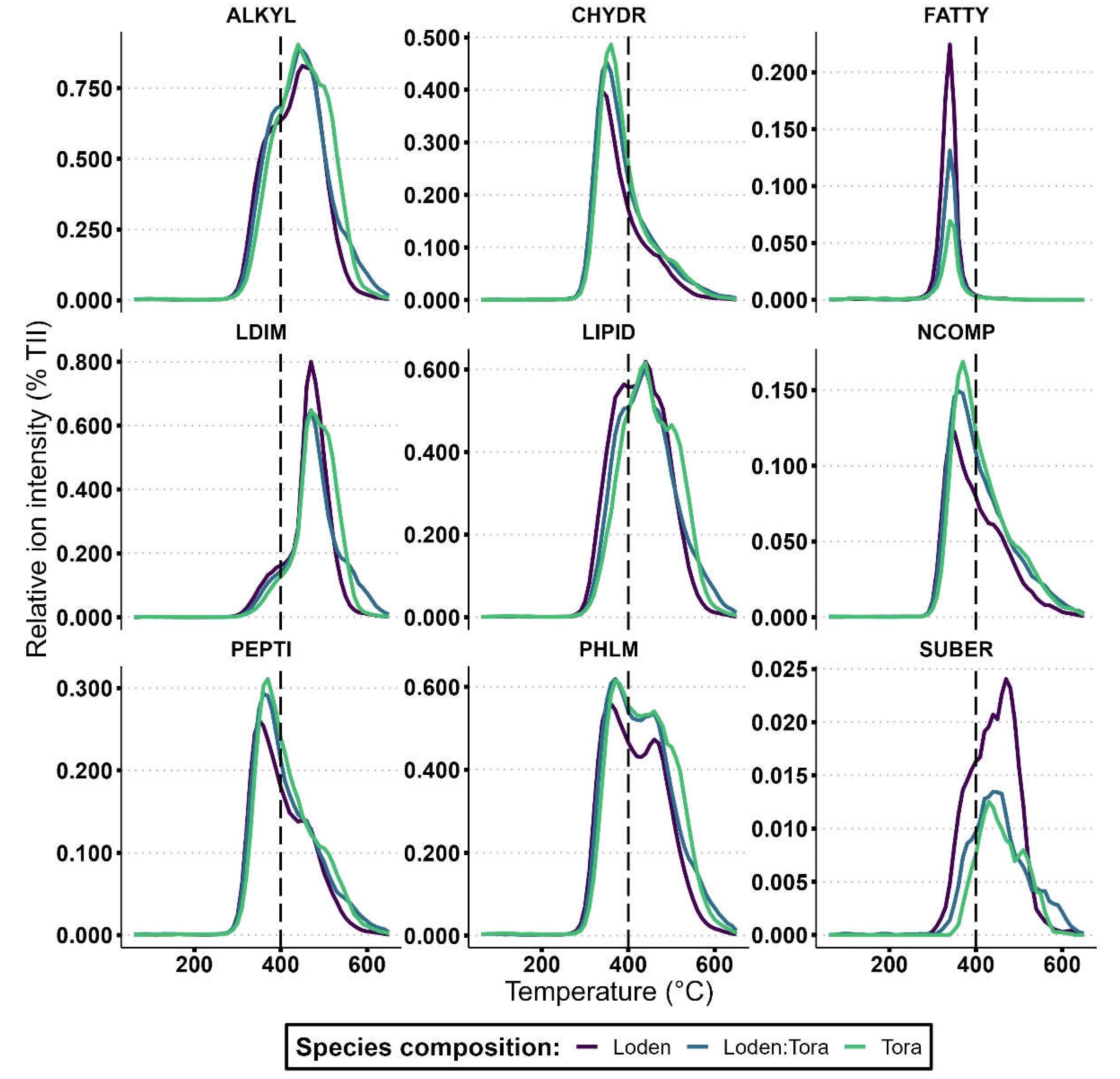

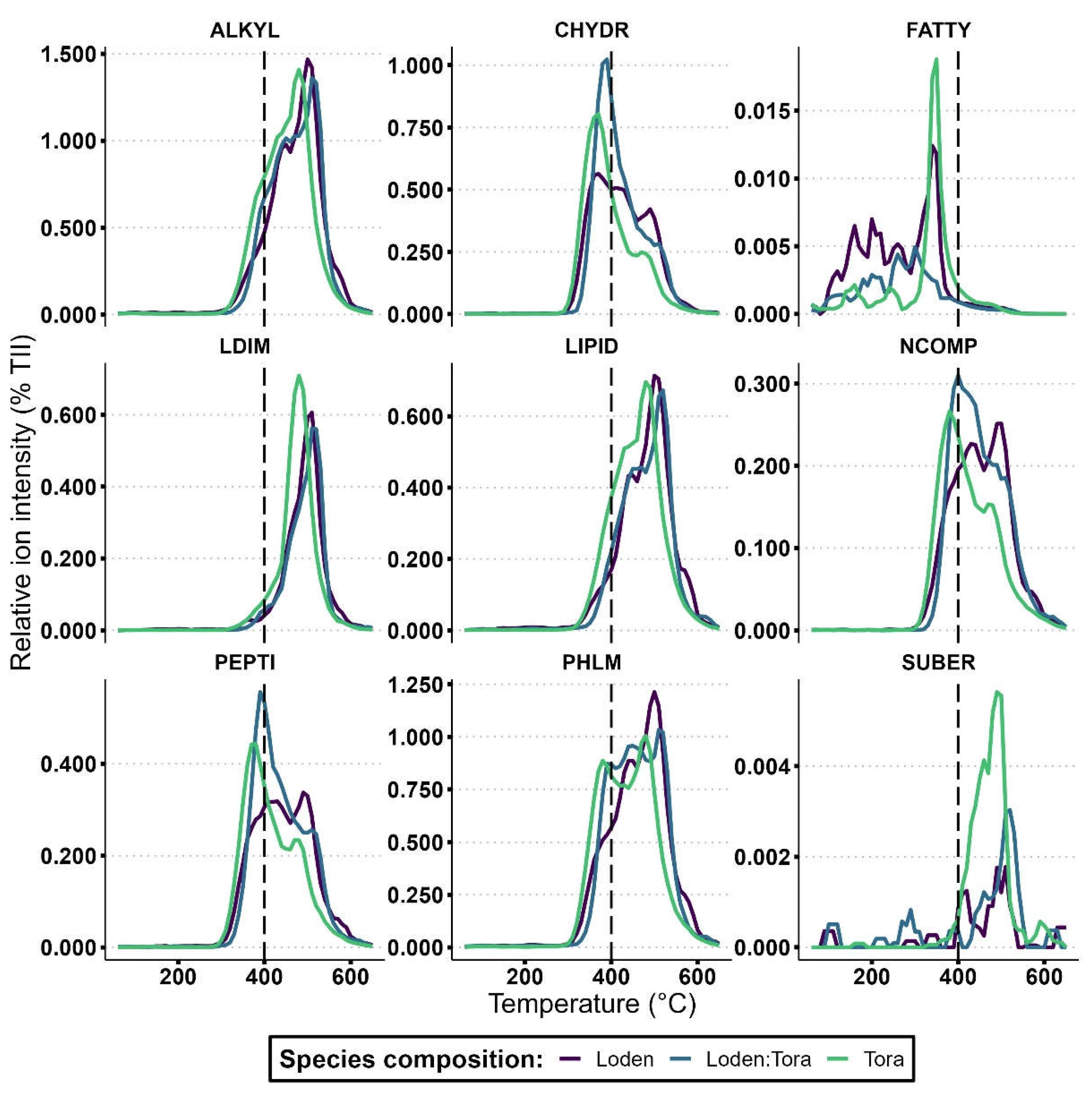

3.2. Effects of Willow Variety

3.3. Effects of Variety Mixing

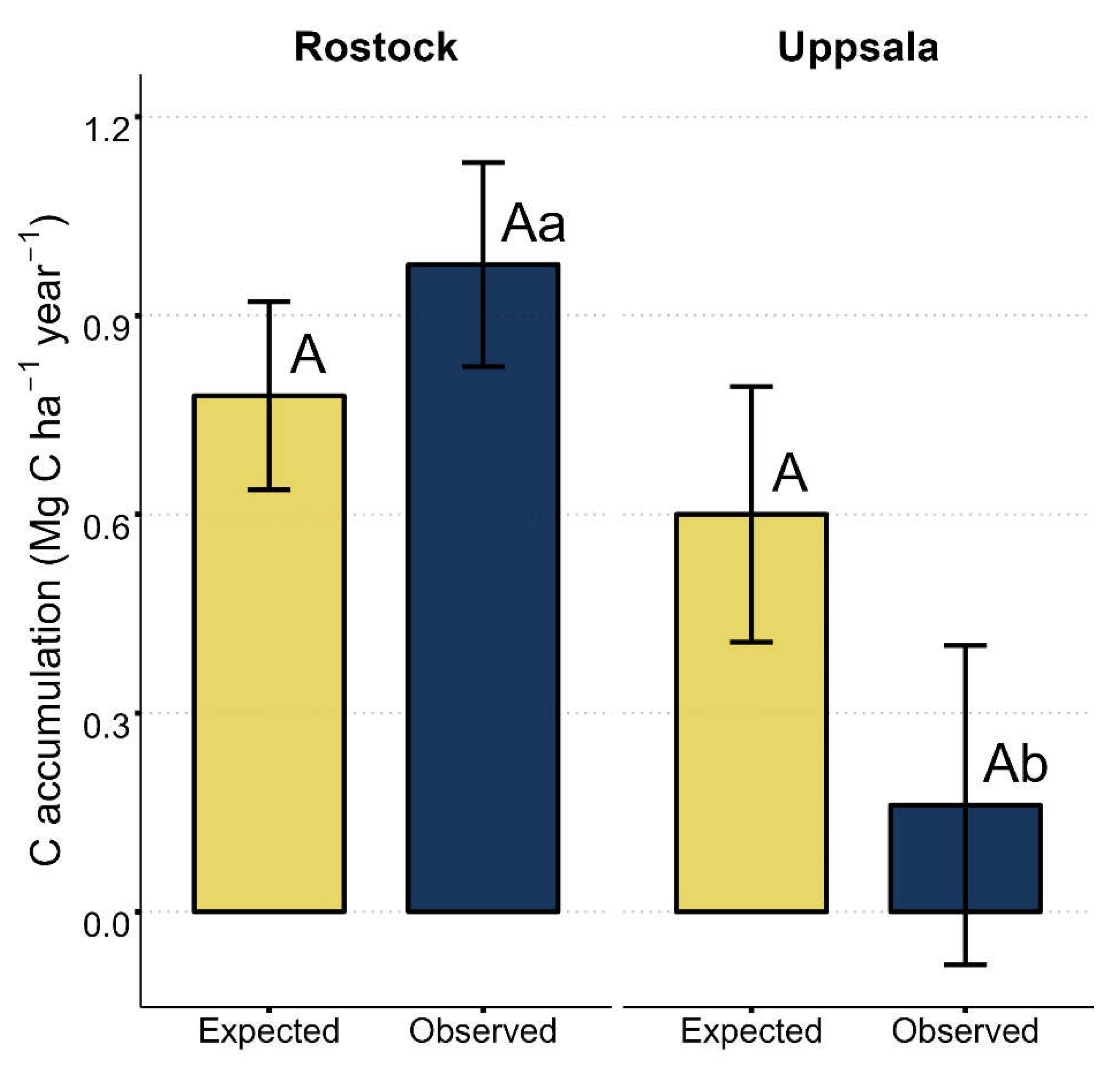

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Site-Specific Environmental Conditions

4.2. Effects of Willow Variety

4.3. Effects of Variety Mixing

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carvalhais, N.; Forkel, M.; Khomik, M.; Bellarby, J.; Jung, M.; Migliavacca, M.; Saatchi, S.; Santoro, M.; Thurner, M.; Weber, U. Global Covariation of Carbon Turnover Times with Climate in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Nature 2014, 514, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, A.A.; Exbrayat, J.-F.; van der Velde, I.R.; Feng, L.; Williams, M. The Decadal State of the Terrestrial Carbon Cycle: Global Retrievals of Terrestrial Carbon Allocation, Pools, and Residence Times. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, P.H.; Loveland, P.J.; Bradley, R.I.; Lark, R.M.; Kirk, G.J. Carbon Losses from All Soils across England and Wales 1978–2003. Nature 2005, 437, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.; Hansel, C.M.; Kaiser, C.; Kleber, M.; Maher, K.; Manzoni, S.; Nunan, N.; Reichstein, M.; Schimel, J.P.; Torn, M.S.; et al. Persistence of Soil Organic Carbon Caused by Functional Complexity. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguenin-Elie, O.; Delaby, L.; Klumpp, K.; Lemauviel-Lavenant, S. The Role of Grasslands in Biogeochemical Cycles and Biodiversity Conservation. In Improving grassland and pasture management in temperate agriculture; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, 2019; pp. 23–50 ISBN 1-351-11456-5.

- Lal, R. Soil Carbon Sequestration to Mitigate Climate Change. Geoderma 2004, 123, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, R.M.; Cambardella, C.A.; Stott, D.E.; Acosta-Martinez, V.; Manter, D.K.; Buyer, J.S.; Maul, J.E.; Smith, J.L.; Collins, H.P.; Halvorson, J.J.; et al. Understanding and Enhancing Soil Biological Health: The Solution for Reversing Soil Degradation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 988–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T.; Bolan, N.S.; Kirkham, M.B.; Wijesekara, H.; Kanchikerimath, M.; Srinivasa Rao, C.; Sandeep, S.; Rinklebe, J.; Ok, Y.S.; Choudhury, B.U.; et al. Chapter One - Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics: Impact of Land Use Changes and Management Practices: A Review. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press, 2019; Vol. 156, pp. 1–107.

- Lehmann, J.; Kleber, M. The Contentious Nature of Soil Organic Matter. Nature 2015, 528, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M. Thermal Adaptation of Decomposer Communities in Warming Soils. Frontiers in Microbiology 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leinweber, P.; Jandl, G.; Baum, C.; Eckhardt, K.-U.; Kandeler, E. Stability and Composition of Soil Organic Matter Control Respiration and Soil Enzyme Activities. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2008, 40, 1496–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleixner, G. Soil Organic Matter Dynamics: A Biological Perspective Derived from the Use of Compound-Specific Isotopes Studies. Ecol Res 2013, 28, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Lützow, M.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Ludwig, B.; Matzner, E.; Flessa, H.; Ekschmitt, K.; Guggenberger, G.; Marschner, B.; Kalbitz, K. Stabilization Mechanisms of Organic Matter in Four Temperate Soils: Development and Application of a Conceptual Model. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 2008, 171, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandl, G.; Leinweber, P.; Schulten, H.-R.; Ekschmitt, K. Contribution of Primary Organic Matter to the Fatty Acid Pool in Agricultural Soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2005, 37, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulten, H.-R.; Leinweber, P. Thermal Stability and Composition of Mineral-Bound Organic Matter in Density Fractions of Soil. European Journal of Soil Science 1999, 50, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensgens, G.; Lechtenfeld, O.J.; Guillemette, F.; Laudon, H.; Berggren, M. Impacts of Litter Decay on Organic Leachate Composition and Reactivity. Biogeochemistry 2021, 154, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarrón-Galeote, M.A.; Trigalet, S.; Wesemael, B. van Soil Organic Carbon Evolution after Land Abandonment along a Precipitation Gradient in Southern Spain. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2015, 199, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Domínguez, B.; Niklaus, P.A.; Studer, M.S.; Hagedorn, F.; Wacker, L.; Haghipour, N.; Zimmermann, S.; Walthert, L.; McIntyre, C.; Abiven, S. Temperature and Moisture Are Minor Drivers of Regional-Scale Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Roux, X.; Schmid, B.; Poly, F.; Barnard, R.L.; Niklaus, P.A.; Guillaumaud, N.; Habekost, M.; Oelmann, Y.; Philippot, L.; Salles, J.F. Soil Environmental Conditions and Microbial Build-up Mediate the Effect of Plant Diversity on Soil Nitrifying and Denitrifying Enzyme Activities in Temperate Grasslands. PLoS One 2013, 8, e61069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frimmel, F.H.; Abbt-Braun, G.; Heumann, K.G.; Hock, B.; Lüdemann, H.-D.; Spiteller, M. Refractory Organic Substances in the Environment; John Wiley & Sons, 2008; ISBN 978-3-527-61444-8.

- Leinweber, P.; Jandl, G.; Eckhardt, K.-U.; Schulten, H.-R.; Schlichting, A.; HofMann, D. Analytical Pyrolysis and Soft-Ionization Mass Spectrometry. In BIOPHYSICO-CHEMICAL PROCESSES INVOLVING NATURAL NONLIVING ORGANIC MATTER IN ENVIRONMENTAL SYSTEMS.; Senesi, N., Xing, B., Huang, P.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, 2009; pp. 539–588.

- Schmidt, L.; Warnstorff, K.; Dörfel, H.; Leinweber, P.; Lange, H.; Merbach, W. The Influence of Fertilization and Rotation on Soil Organic Matter and Plant Yields in the Long-Term Eternal Rye Trial in Halle (Saale), Germany. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 2000, 163, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.; McClaugherty, C. Plant Litter: Decomposition, Humus Formation, Carbon Sequestration; Springer Nature, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-59631-6.

- Warembourg, F.R.; Roumet, C.; Lafont, F. Differences in Rhizosphere Carbon-Partitioning among Plant Species of Different Families. Plant and Soil 2003, 256, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto, L.; Boča, A. Tree Functional Traits, Forest Biomass, and Tree Species Diversity Interact with Site Properties to Drive Forest Soil Carbon. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, W.; Xu, W.; Wang, Y.; Wan, H.; Chen, D.; Tang, Z.; Tang, X.; Zhou, G.; Xie, Z.; et al. Plant Diversity Enhances Productivity and Soil Carbon Storage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 4027–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawud, S.M.; Raulund-Rasmussen, K.; Domisch, T.; Finér, L.; Jaroszewicz, B.; Vesterdal, L. Is Tree Species Diversity or Species Identity the More Important Driver of Soil Carbon Stocks, C/N Ratio, and pH? Ecosystems 2016, 19, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Crowther, T.W.; Picard, N.; Wiser, S.; Zhou, M.; Alberti, G.; Schulze, E.-D.; McGuire, A.D.; Bozzato, F.; Pretzsch, H.; et al. Positive Biodiversity-Productivity Relationship Predominant in Global Forests. Science 2016, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Schulze, E.-D.; Don, A.; Schumacher, J.; Weller, E. Exploring the Functional Significance of Forest Diversity: A New Long-Term Experiment with Temperate Tree Species (BIOTREE). Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 2007, 9, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucker, T.; Avăcăriței, D.; Bărnoaiea, I.; Duduman, G.; Bouriaud, O.; Coomes, D.A. Climate Modulates the Effects of Tree Diversity on Forest Productivity. Journal of Ecology 2016, 104, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, S.; Wirth, C.; Jucker, T.; van der Plas, F.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Verheyen, K.; Allan, E.; Benavides, R.; Bruelheide, H.; Ohse, B.; et al. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning Relations in European Forests Depend on Environmental Context. Ecology Letters 2017, 20, 1414–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrow, J.D.; Amonette, J.E.; Bailey, V.L. Mechanisms Controlling Soil Carbon Turnover and Their Potential Application for Enhancing Carbon Sequestration. Climatic Change 2007, 80, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moujahid, L.E.; Roux, X.L.; Michalet, S.; Bellvert, F.; Weigelt, A.; Poly, F. Effect of Plant Diversity on the Diversity of Soil Organic Compounds. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0170494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Freedman, Z.B.; Liu, P.; Cong, W.; Wang, J.; Zang, R.; Liu, S. Evenness of Soil Organic Carbon Chemical Components Changes with Tree Species Richness, Composition and Functional Diversity across Forests in China. Global Change Biology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Song, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; You, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Z.; Nong, Y.; Ming, A.; et al. Introducing Nitrogen-Fixing Tree Species and Mixing with Pinus Massoniana Alters and Evenly Distributes Various Chemical Compositions of Soil Organic Carbon in a Planted Forest in Southern China. Forest Ecology and Management 2019, 449, 117477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugnon, R.; Eisenhauer, N.; Bruelheide, H.; Davrinche, A.; Du, J.; Haider, S.; Hähn, G.; Saadani, M.; Singavarapu, B.; Sünnemann, M. Tree Diversity Effects on Litter Decomposition Are Mediated by Litterfall and Microbial Processes. Oikos 2023, e09751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, D.A.; Nicholson, K.S. Synergistic Effects of Grassland Plant Spcies on Soil Microbial Biomass and Activity: Implications for Ecosystem-Level Effects of Enriched Plant Diversity. Functional Ecology 1996, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubsch, M.; Roscher, C.; Gleixner, G.; Habekost, M.; Lipowsky, A.; Schmid, B.; SCHULZE, E.; Steinbeiss, S.; Buchmann, N. Foliar and Soil δ15N Values Reveal Increased Nitrogen Partitioning among Species in Diverse Grassland Communities. Plant, Cell & Environment 2011, 34, 895–908. [Google Scholar]

- Niklaus, P.A.; Le Roux, X.; Poly, F.; Buchmann, N.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Weigelt, A.; Barnard, R.L. Plant Species Diversity Affects Soil–Atmosphere Fluxes of Methane and Nitrous Oxide. Oecologia 2016, 181, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Amelung, W.; Lehmann, J.; Kästner, M. Quantitative Assessment of Microbial Necromass Contribution to Soil Organic Matter. Global Change Biology 2019, 25, 3578–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Soil Microbiomes and One Health. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, D.U.; Chapin, F.S.; Ewel, J.J.; Hector, A.; Inchausti, P.; Lavorel, S.; Lawton, J.H.; Lodge, D.M.; Loreau, M.; Naeem, S.; et al. Effects of Biodiversity on Ecosystem Functioning: A Consensus of Current Knowledge. Ecological Monographs 2005, 75, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, F.; Calcagno, V.; Hector, A.; Connolly, J.; Harpole, W.S.; Reich, P.B.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Schmid, B.; Tilman, D.; van Ruijven, J.; et al. High Plant Diversity Is Needed to Maintain Ecosystem Services. Nature 2011, 477, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souto, X.C.; Chiapusio, G.; Pellissier, F. Relationships Between Phenolics and Soil Microorganisms in Spruce Forests: Significance for Natural Regeneration. J Chem Ecol 2000, 26, 2025–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, A.; Shield, I. Bioenergy from Plants and the Sustainable Yield Challenge. New Phytologist 2008, 179, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weih, M.; Hansson, P.-A.; Ohlsson, J.; Sandgren, M.; Schnürer, A.; Rönnberg-Wästljung, A.-C. Sustainable Production of Willow for Biofuel Use. In Achieving carbon negative bioenergy systems from plant materials; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, 2020; pp. 305–340.

- Weih, M. Willow. In Biofuel crops: production, physiology and genetics; CABI, 2013; pp. 415-426 ISBN 978-1- 84593-885-7.

- Weih, M.; Glynn, C.; Baum, C. Willow Short-Rotation Coppice as Model System for Exploring Ecological Theory on Biodiversity–Ecosystem Function. Diversity 2019, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindh, M.; Hoeber, S.; Weih, M.; Manzoni, S. Interactions of Nutrient and Water Availability Control Growth and Diversity Effects in a Salix Two-Species Mixture. Ecohydrology 2022, 15, e2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weih, M.; Nordh, N.-E.; Manzoni, S.; Hoeber, S. Functional Traits of Individual Varieties as Determinants of Growth and Nitrogen Use Patterns in Mixed Stands of Willow (Salix Spp.). Forest Ecology and Management 2021, 479, 118605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, C.; Amm, T.; Kahle, P.; Weih, M. Fertilization Effects on Soil Ecology Strongly Depend on the Genotype in a Willow (Salix Spp.) Plantation. Forest Ecol Manag 2020, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, C.; Leinweber, P.; Weih, M.; Lamersdorf, N.; Dimitriou, I. Effects of Short Rotation Coppice with Willows and Poplar on Soil Ecology. Agriculture and Forestry Research 2009, 3, 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kalita, S.; Potter, H.K.; Weih, M.; Baum, C.; Nordberg, Å.; Hansson, P.-A. Soil Carbon Modelling in Salix Biomass Plantations: Variety Determines Carbon Sequestration and Climate Impacts. Forests 2021, 12, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeber, S.; Fransson, P.; Prieto-Ruiz, I.; Manzoni, S.; Weih, M. Two Salix Genotypes Differ in Productivity and Nitrogen Economy When Grown in Monoculture and Mixture. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verheyen, K.; Vanhellemont, M.; Auge, H.; Baeten, L.; Baraloto, C.; Barsoum, N.; Bilodeau-Gauthier, S.; Bruelheide, H.; Castagneyrol, B.; Godbold, D.; et al. Contributions of a Global Network of Tree Diversity Experiments to Sustainable Forest Plantations. Ambio 2016, 45, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISRIC, F. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. World soil resources reports 1998, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, C.; Hrynkiewicz, K.; Szymańska, S.; Vitow, N.; Hoeber, S.; Fransson, P.M.A.; Weih, M. Mixture of Salix Genotypes Promotes Root Colonization With Dark Septate Endophytes and Changes P Cycling in the Mycorrhizosphere. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weih, M.; Nordh, N.-E. Characterising Willows for Biomass and Phytoremediation: Growth, Nitrogen and Water Use of 14 Willow Clones under Different Irrigation and Fertilisation Regimes. Biomass and Bioenergy 2002, 23, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågren, G.I.; Weih, M. Plant Stoichiometry at Different Scales: Element Concentration Patterns Reflect Environment More than Genotype. New Phytologist 2012, 194, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeber, S.; Fransson, P.; Weih, M.; Manzoni, S. Leaf Litter Quality Coupled to Salix Variety Drives Litter Decomposition More than Stand Diversity or Climate. Plant Soil 2020, 453, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Huang, Q.; Yuan, S.; Yang, X.; Dong, J. Characterization of Cadmium-Resistant Endophytic Fungi from Salix Variegata Franch. in Three Gorges Reservoir Region, China. Microbiological Research 2015, 176, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrynkiewicz, K.; Ciesielska, A.; Haug, I.; Baum, C. Ectomycorrhiza Formation and Willow Growth Promotion as Affected by Associated Bacteria: Role of Microbial Metabolites and Use of C Sources. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2010, 46, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Püttsepp, Ü.; Rosling, A.; Taylor, A.F.S. Ectomycorrhizal Fungal Communities Associated with Salix Viminalis L. and S. Dasyclados Wimm. Clones in a Short-Rotation Forestry Plantation. Forest Ecology and Management 2004, 196, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeber, S.; Arranz, C.; Nordh, N.E.; Baum, C.; Low, M.; Nock, C.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Weih, M. Genotype Identity Has a More Important Influence than Genotype Diversity on Shoot Biomass Productivity in Willow Short-Rotation Coppices. Gcb Bioenergy 2018, 10, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunniff, J.; Purdy, S.J.; Barraclough, T.J.P.; Castle, M.; Maddison, A.L.; Jones, L.E.; Shield, I.F.; Gregory, A.S.; Karp, A. High Yielding Biomass Genotypes of Willow (Salix Spp.) Show Differences in below Ground Biomass Allocation. Biomass and Bioenergy 2015, 80, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rytter, R.-M.; Hansson, A.-C. Seasonal Amount, Growth and Depth Distribution of Fine Roots in an Irrigated and Fertilized Salix Viminalis L. Plantation. Biomass and Bioenergy 1996, 11, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VDLUFA Methode A 6.2.1.2 - Bestimmung von Phosphor Und Kalium Im Doppellactat (DL)-Auszug. In VDLUFA-Methodenbuch, Band I, Die Untersuchung von Boden; Verband Deutscher Landwirtschaftlicher Untersuchungs- und, Forschungsanstalten, Ed.; VDLUFA-Verlag: Darmstadt, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hylander, L.D.; Svensson, H.; Simán, G. Different Methods for Determination of Plant Available Soil Phosphorus. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 1996, 27, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, T.C.; Clemmensen, K.E.; Friggens, N.L.; Hartley, I.P.; Johnson, D.; Lindahl, B.D.; Olofsson, J.; Siewert, M.B.; Street, L.E.; Subke, J.-A.; et al. Rhizosphere Allocation by Canopy-Forming Species Dominates Soil CO2 Efflux in a Subarctic Landscape. New Phytologist 2020, 227, 1818–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oades, J.M. Soil Organic Matter and Structural Stability: Mechanisms and Implications for Management. Plant Soil 1984, 76, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempfling, R.; Zech, W.; Schulten, H.-R. CHEMICAL COMPOSITION OF THE ORGANIC MATTER IN FOREST SOILS: 2. MODER PROFILE. Soil Science 1988, 146, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinweber, P.; Kruse, J.; Baum, C.; Arcand, M.; Knight, J.D.; Farrell, R.; Eckhardt, K.-U.; Kiersch, K.; Jandl, G. Chapter Two - Advances in Understanding Organic Nitrogen Chemistry in Soils Using State-of-the-Art Analytical Techniques. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Advances in Agronomy; Academic Press, 2013; Vol. 119, pp. 83–151.

- Leinweber, P.; Blumenstein, O.; Schulten, H.-R. Organic Matter Composition in Sewage Farm Soils: Investigations by 13C-NMR and Pyrolysis-Field Ionization Mass Spectrometry. European Journal of Soil Science 1996, 47, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzer, M.; Schulten, H.R. The Analysis of Soil Organic Matter by Pyrolysis-Field Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Soil Science Society of America Journal 1992, 56, 1811–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core, R. TEAM, 2017. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Online: https://www. r-project. org, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’hara, R.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Wagner, H. Package ‘Vegan. ’ Community ecology package, version 2013, 2, 1–295. [Google Scholar]

- Keithley, R.B.; Mark Wightman, R.; Heien, M.L. Multivariate Concentration Determination Using Principal Component Regression with Residual Analysis. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2009, 28, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, K.; Eckhardt, K.-U.; Schöning, I.; Schrumpf, M.; Leinweber, P. Clay Fraction Properties and Grassland Management Imprint on Soil Organic Matter Composition and Stability at Molecular Level. Soil Use and Management 2022, 38, 1578–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, J.; Bates, D.; DebRoy, S.; Sarkar, D. Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Models. R package version 2012, 3, 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth, R.; Singmann, H.; Love, J.; Buerkner, P.; Herve, M. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 2018, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, M.J.; Mueller, K.E.; Olk, D.C.; Sawyer, J.E.; Six, J. Integrating Plant Litter Quality, Soil Organic Matter Stabilization, and the Carbon Saturation Concept. Global change biology 2015, 21, 3200–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, K.; Dignac, M.-F.; Rumpel, C.; Bardoux, G.; Sarr, A.; Steffens, M.; Maron, P.-A. Soil Microbial Diversity Affects Soil Organic Matter Decomposition in a Silty Grassland Soil. Biogeochemistry 2013, 114, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, K.M.; Matson, P.A. The Influence of Tropical Plant Diversity and Composition on Soil Microbial Communities. Microb Ecol 2006, 52, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, U.; Adams, M.A.; Crawford, J.W.; Field, D.J.; Henakaarchchi, N.; Jenkins, M.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B.; Courcelles, V. de R. de; Singh, K.; et al. The Knowns, Known Unknowns and Unknowns of Sequestration of Soil Organic Carbon. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2013, 164, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, M.V.; Christensen, B.T.; Sørensen, L.H. Labelled and Native Sugars in Particle-Size Fractions from Soils Incubated with 14C Straw for 6 to 18 Years. Journal of Soil Science 1990, 41, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angst, G.; Heinrich, L.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Mueller, C.W. The Fate of Cutin and Suberin of Decaying Leaves, Needles and Roots – Inferences from the Initial Decomposition of Bound Fatty Acids. Organic Geochemistry 2016, 95, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jansen, B.; Absalah, S.; Kalbitz, K.; Chunga Castro, F.O.; Cammeraat, E.L.H. Soil Organic Carbon Content and Mineralization Controlled by the Composition, Origin and Molecular Diversity of Organic Matter: A Study in Tropical Alpine Grasslands. Soil and Tillage Research 2022, 215, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgil, R.L.; Gadgil, P. Mycorrhiza and Litter Decomposition. Nature 1971, 233, 133–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, M.; Kern, N.V.; Prietzel, J. Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Stocks under Pure and Mixed Stands of European Beech, Douglas Fir and Norway Spruce. Forest Ecology and Management 2016, 367, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, B.G.; Smith, K.R.; Belluau, M.; Khlifa, R.; Messier, C.; Munson, A.; Paquette, A. Soil Carbon Pools Are Affected by Species Identity and Productivity in a Tree Common Garden Experiment. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmeier, M.; Prietzel, J.; Barthold, F.; Spörlein, P.; Geuß, U.; Hangen, E.; Reischl, A.; Schilling, B.; von Lützow, M.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Storage and Drivers of Organic Carbon in Forest Soils of Southeast Germany (Bavaria) – Implications for Carbon Sequestration. Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 295, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczorski, P.; Furtado, B.U.; Gołębiewski, M.; Hulisz, P.; Baum, C.; Weih, M.; Hrynkiewicz, K. The Effects of Host Plant Genotype and Environmental Conditions on Fungal Community Composition and Phosphorus Solubilization in Willow Short Rotation Coppice. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, K.E.; Weigelt, A.; van Ruijven, J.; de Kroon, H.; Ebeling, A.; Eisenhauer, N.; Gessler, A.; Ravenek, J.M.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Oram, N.J.; et al. Chapter Two - Above- and Belowground Overyielding Are Related at the Community and Species Level in a Grassland Biodiversity Experiment. In Advances in Ecological Research; Eisenhauer, N., Bohan, D.A., Dumbrell, A.J., Eds.; Mechanisms underlying the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem function; Academic Press, 2019; Vol. 61, pp. 55–89.

- Hall, S.J.; Huang, W.; Timokhin, V.I.; Hammel, K.E. Lignin Lags, Leads, or Limits the Decomposition of Litter and Soil Organic Carbon. Ecology 2020, 101, e03113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Site | Soil group | pH | Bulk density [g cm-3] |

Clay content [%] |

MAT [° C] |

MAP [mg g-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uppsala | Vertic Cambisol | 5.2 | 1.4 | 52 | 7.53 | 500 |

| Rostock | Stagnic Cambisol | 6.2 | 1.3 | 5 | 10.35 | 730 |

| Py-FIMS parameters | Explanations |

|---|---|

| Hexoses:pentoses | Ratio of microbial- to plant-derived sugars |

| TII | Total ion intensity (106 counts mg-1) |

| VM | Volatile matter in % (weightbefore pyrolysis/weightafter pyrolysis) |

| CHYDR | Carbohydrates with pentose and hexose subunits |

| PHLM | Phenols and lignin monomers |

| LDIM | Lignin dimers |

| LIPID | Lipids, alkanes, alkenes, bound fatty acids, and alkylmonoesters |

| ALKYL | Alkylaromatics |

| NCOMP | Mainly heterocyclic N-containing compounds |

| PEPTI | Peptides (amino acids, peptides and aminosugars) |

| SUBER | Suberin |

| FATTY | Free fatty acids C16-C34 |

| Site | Variety composition |

C:N | C [%] |

N [%] |

Kdl~~·[mg g-1] | Mgdl [mg g-1] |

Pdl [mg g-1] |

CO2 [g C m-2 h-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rostock | ‘Loden’ | 10.80 xa | 1.26 ya | 0.12 ya | 9.99 ya | 20.42 ya | 4.40 xa | - |

| ‘Loden’:‘Tora’ | 10.63 xa | 1.22 ya | 0.11 ya | 10.22 ya | 21.06 ya | 4.40 xa | - | |

| ‘Tora’ | 10.22 xa | 1.01 ya | 0.10 ya | 10.71 ya | 21.96 ya | 4.02 xa | - | |

| Uppsala | ‘Loden’ | 10.69 xa | 1.89 xa | 0.18 xa | 22.23 xa | 32.10 xa | 4.27 xa | 0.493 a |

| ‘Loden’:‘Tora’ | 10.58 xa | 1.58 xa | 0.16 xa | 23.62 xa | 27.94 xa | 5.04 xa | 0.453 a | |

| ‘Tora’ | 10.85 xa | 1.90 xa | 0.17 xa | 19.89 xa | 28.76 xa | 3.60 xa | 0.461 a |

| Site | Variety composition |

TII [106 counts mg-1] |

Total thermal stability |

Chemical diversity [H’] |

Hexoses: pentoses |

Volatile matter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rostock | ‘Loden’ | 53.3 xa | 0.68 xa | 6.71 ya | 5.79 xa | 2.83 xa |

| ‘Loden’:‘Tora’ | 39.1 xa | 0.72 xa | 6.30 ya | 5.73 xab | 2.92 xa | |

| ‘Tora’ | 34.8 xa | 0.77 xa | 5.82 ya | 5.67 xb | 2.75 xa | |

| Uppsala | ‘Loden’ | 14.8 ya | 0.84 xa | 14.66 xa | 5.47 ya | 1.89 yb |

| ‘Loden’:‘Tora’ | 14.2 ya | 0.82 xb | 9.69 xb | 5.45 ya | 1.91 yb | |

| ‘Tora’ | 24.7 ya | 0.83 xab | 13.36 xa | 5.53 ya | 2.28 ya |

| Compound classes | Rostock | Uppsala | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Loden’ | ‘Tora’ | ‘Loden’ | ‘Tora’ | ||

| CHYDR | 4.0 (0.19) Bb | 5.0 (0. 19) Ab | 9.5 (0.82) Aa | 8.8 (0.82) Aa | |

| PHLM | 9.9 (0.36) Bb | 11.7 (0.36) Ab | 17.2 (0.82) Aa | 16.2 (0.82) Aa | |

| LDIM | 6.8 (0.64) Aa | 7.1 (0.64) Aa | 4.2 (0.59) Bb | 5.9 (0.59) Aa | |

| LIPID | 10.3 (0.29) Aa | 9.9 (0.29) Aa | 8.4 (0.24) Ab | 8.8 (0.24) Ab | |

| ALKYL | 13.3 (0.49) Ab | 14.9 (0.49) Ab | 17.8 (0.38) Aa | 17.9 (0.38) Aa | |

| NCOMP | 1.6 (0. 10) Bb | 2.1 (0.10) Ab | 4.1 (0.36) Aa | 3.6 (0. 36) Aa | |

| PEPTI | 3.6 (0.24) Bb | 4.1 (0.24) Ab | 6.4 (0.21) Aa | 5.5 (0.21) Ba | |

| SUBER | 0.33 (0.03) Aa | 0.16 (0.03) Ba | 0.02 (0.01) Ab | 0.05 (0.01) Ab | |

| FATTY | 0.87 (0.13) Aa | 0.31 (0.13) Ba | 0.17 (0.07) Ab | 0.04 (0.07) Ba | |

| Compound classes | Rostock | Uppsala | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Loden’ | ‘Tora’ | ‘Loden’ | ‘Tora’ | ||

| CHYDR | 0.32 (0.08) Aa | 0.36 (0.08) Aa | 0.60 (0.08) Aa | 0.51 (0.08) Ba | |

| PHLM | 0.58 (0.06) Ab | 0.67 (0.06) Aa | 0.82 (0.05) Aa | 0.77 (0.05) Ba | |

| LDIM | 0.88 (0.02) Ba | 0.93 (0.02) Aa | 0.95 (0.02) Aa | 0.97 (0.02) Aa | |

| LIPID | 0.67 (0.04) Bb | 0.80 (0.04) Aa | 0.90 (0.03) Aa | 0.90 (0.03) Aa | |

| ALKYL | 0.70 (0.04) Bb | 0.80 (0.04) Aa | 0.88 (0.04) Aa | 0.87 (0.04) Ba | |

| NCOMP | 0.46 (0.07) Ab | 0.53 (0.07) Aa | 0.80 (0.06) Aa | 0.68 (0.06) Ba | |

| PEPTI | 0.48 (0.07) Aa | 0.54 (0.07) Aa | 0.72 (0.06) Aa | 0.64 (0.06) Ba | |

| SUBER | 0.76 (0.06) Ba | 0.90 (0.06) Aa | 0.88 (0.05) Ba | 0.97 (0.05) Aa | |

| FATTY | 0.02 (0.01) Ba | 0.07 (0.01) Aa | 0.10 (0.07) Aa | 0.12 (0.07) Aa | |

| Compound classes |

Rostock | Uppsala | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected | Observed | NDE | Expected | Observed | NDE | ||

| CHYDR | 4.6 (0.14) | 5.0 (0.19) | 9.2% n.s. | 9.0 (0.62) | 10.6 (0.82) | 17.1% n.s. | |

| PHLM | 11.0 (0.26) | 11.6 (0.36) | 5.8% n.s. | 16.5 (0.63) | 17.4 (0.82) | 5.7% n.s. | |

| LDIM | 7.0 (0.62) | 6.6 (0.64) | -5.6% n.s. | 5.4 (0.59) | 4.4 (0.59) | -18.3% *** | |

| LIPID | 10.1 (0.23) | 9.9 (0.29) | -1.9% n.s. | 8.6 (0.20) | 8.0 (0.24) | -7.2% n.s. | |

| ALKYL | 14.2 (0.35) | 14.6 (0.49) | 2.8% n.s. | 17.8 (0.29) | 17.6 (0.38) | -1.0% n.s. | |

| NCOMP | 1.9 (0.07) | 2.1 (0.25) | 10.2% n.s. | 3.8 (0.27) | 4.5 (0.23) | 20.1% n.s. | |

| PEPTI | 3.9 (0.22) | 4.1 (0.24) | 4.0% n.s. | 5.8 (0.20) | 6.8 (0.21) | 18.2% *** | |

| SUBER | 0.23 (0.03) | 0.20 (0.03) | -14.8% n.s. | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) | -18.0% n.s. | |

| FATTY | 0.55 (0.10) | 0.52 (0.13) | -6.5% n.s. | 0.08 (0.07) | 0.13 (0.07) | 59.4% n.s. | |

| Compound classes |

Rostock | Uppsala | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected | Observed | NDE | Expected | Observed | NDE | ||

| CHYDR | 0.34 (0.08) | 0.36 (0.08) | 3.3% n.s. | 0.54 (0.08) | 0.53 (0.08) | -1.0% n.s. | |

| PHLM | 0.63 (0.05) | 0.63 (0.06) | -1.0% n.s. | 0.78 (0.05) | 0.78 (0.05) | 0.3% n.s. | |

| LDIM | 0.91 (0.02) | 0.91 (0.02) | -0.6% n.s. | 0.96 (0.02) | 0.95 (0.02) | -1.5% n.s. | |

| LIPID | 0.74 (0.04) | 0.74 (0.04) | -0.7% n.s. | 0.90 (0.03) | 0.90 (0.03) | 0.4% n.s. | |

| ALKYL | 0.76 (0.04) | 0.74 (0.04) | -2.0% n.s. | 0.87 (0.04) | 0.86 (0.04) | -0.9% * | |

| NCOMP | 0.48 (0.06) | 0.50 (0.07) | -0.2% n.s. | 0.71 (0.06) | 0.74 (0.06) | 3.55% n.s. | |

| PEPTI | 0.52 (0.07) | 0.50 (0.07) | -2.5% n.s. | 0.67 (0.07) | 0.67 (0.06) | 0.4% n.s. | |

| SUBER | 0.84 (0.05) | 0.83 (0.06) | -1.8% n.s. | 0.99 (0.05) | 0.76 (0.05) | -22.7% *** | |

| FATTY | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | -19.8% n.s. | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.15 (0.07) | 30.8% n.s. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).