“Yet mark’d I where the bolt of Cupid fell:It fell upon a little western flower,Before milk-white, now purple with love’s wound,And maidens call it love-in-idleness.” William Shakespeare, A midsummer night’s dream (Act II, Scene 1)

The search for a love potion has long been appealing to human imagination. Throughout history folk recipes prescribed the use of herbs, roots, animals body parts or products, and human excretes as common ingredients of formulations allegedly capable of influencing someone else’s love feelings and/or erotic interests (Leonti and Casu, 2018). One example is the mandrake root, used as an anesthetic, aphrodisiac and fertility drug, and magic until the 17th century. Casanova, the Italian unrepentant seducer, reputedly ate fifty oysters each morning (and as many before each gallant meeting) and the Aztec emperor Montezuma drank an equal number of chocolate cups a day to sustain his sexual performances (Flight, 2021). The rationale behind the choice of ingredients is not always comprehensible to the modern mind while scientific investigation is now beginning to discriminate between facts and myths. Indeed, oysters have been found to contain exceptional high levels of zinc whose deficiency in humans has been related to reduced serum testosterone concentrations and seminal volume (Hunt et al., 1992). More recently, perfumes and lotions containing putative human sexual pheromones are being advertised promoting to help “to attract the woman of your dreams” and “be the most desired man in the room”. However, to date and despite the miraculous claims no molecule has been identified that meets the criteria of the definition of pheromone for the human species (Wyatt, 2015).

Literary works and, in the last two centuries, comics, cartoons and movies have often take up the trope of love potions or powder. In many cases, the concoction will cast a spell on the unsuspecting victim making her fall for the next person she sees, like the juice of the wild pansy in Shakespeare’s comedy that turns Lysander’s and Demetrius’s love towards Helena. One of its latest depictions is found in the 2015 Lucasfilm animation picture Strange Magic, where the main ingredient of the potion is the innocuous Primula flowers which grows all along the border between the bright Fairy Kingdom and the gloomy Dark Forest; like love, as they say, hanging in the balance between passion and hate.

Given these premises, the idea that there could be a “love molecule” out there (or in here) certainly appeals to the more scientifically inclined popular imagination of today. Our principal candidate for about forty years now has been the organic compound β-phenylethylamine (PEA) (Otherwise named phenethylamine and 2-phenylethylamine, which is its proper chemical name (Irsfeld et al., 2013).), a molecule naturally found in food and member of the monoamine family endogenous to the human body. PEA belongs to the group of the trace amines together with tryptamine, octopamine, and other metabolically related compounds present in the brain at low concentrations (Branchek and Blackburn, 2003).

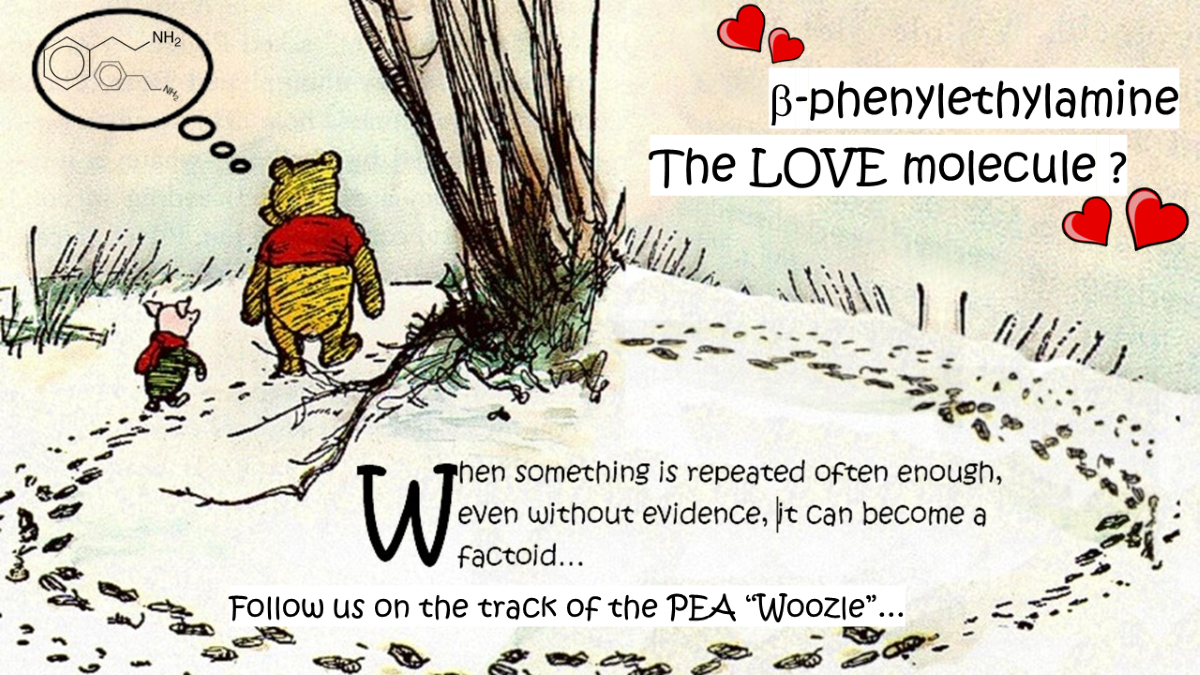

Surfing the web, one can find dozens of newspapers, articles and blog entries written by scientific journalists and physicians indicating PEA as the chimerical “love drug” that assists the human species igniting the spark of infatuation. Indeed, behavioral neuropharmacology studies has found attraction in mammals and birds to be associated with increased or decreased levels of one or more of the monoamine neurotransmitters circulating in the brain (Fisher, 1998). However, a Pubmed advanced search with “phenylethylamine” and “love” as items in the Title/Abstract fields retrieved no results. So, at least as a catch phrase, the association of the two terms appears to have never been used in the medical literature. Reviewing the literature, we will learn that this attribution is purely speculative but one of those that easily go viral among the general public. What can happen is that when a source is being widely cited for a claim it does not adequately support it could give rise to a false credence in the claim coming from multiple independent sources, affecting further research. This amount to the Woozle effect, after the imaginary character of which Winnie-the-Pooh and Piglet start following the tracks that later reveal to be their own (Wikimedia contributors, 2023).

The Stages of Romantic Love

A theory proposed by the American biological anthropologist Helen Fisher maintains that there exists three stages of falling in love, namely lust, attraction, and attachment (Fisher, 1998). In her view, each stage is associated with a different set of hormones and neurotransmitters that accounts for emotional and motivational distinct features. While sex hormones like testosterone and estrogens are long known to drive the research of a sexual partner in the first stage (Sherwin, 1994), serotonin and cathecolamines like noradrenaline and dopamine are suggested to be involved in the second stage (attraction). This is the moment in which almost nothing could distract us from thinking about our desired partner. Dopamine is the chemical that triggers our motivation and anticipates the reward of sexual coupling (Takahashi et al., 2015). Also, it is believed to increase our energy and reduce the need for sleep and food in analogy with the effects of drugs that enhances dopamine release (Koob et al., 2020). The obsessive aspect of love of which a distorted judgment about the beloved one is a prominent feature would instead be driven by the alteration of serotonin metabolism, possibly showing gender differences (Langeslag et al., 2012; Marazziti et al., 1999). The early phases of romantic love does shares many psychological aspects with obsessive-compulsive disorder although this relation is only limitedly substantiated by neurochemical investigation (McLauchlan et al., 2022; Feygin et al., 2006).

Bertrand Russell wrote that love “is a state of illusion, serving the ends of Nature” (Russell, 1916): the last phase (attachment) is the bet evolution won to aid in the preservation of the human species. It is thought to be dependent on two other neurohormones, oxytocin and vasopressin, released during and after intercourse and responsible to bond the lovers together (Bernaerts et al., 2017; Carter, 2017). This would help building a lasting monogamous pair for rearing vulnerable offspring but in this final stage the exhilaration of the precedent two phases can be long lost. Popular culture says romance can’t last forever, but “real love” do. As a matter of fact, there are few fortunate couples for whom it seems the romantic attraction persists over time due do the sustained activity of the so-called dopaminergic reward system. In these individuals, viewing facial images of their partner still induces a strong activation of the ventral tegmental area, one of the two largest dopaminergic regions of the brain (Acevedo et al., 2012).

PEA PEA on the Wall…

Keeping the partly speculative Fisher’s account in mind, where does PEA comes in? PEA is one of the bodily monoamine supposedly involved in the second stage of attraction. Marazziti and Canale (2004) plainly wrote:

“One of the first biological hypotheses with regard to falling in love associates this state to increased levels of phenylethylamine, on the basis of the similarities between the chemical structure of this neurotransmitter and that of amphetamines which provoke mood changes resembling those typical of the initial stage of a romance; however, no empirical data have been gathered to support this theory [emphasis added].”

The two researchers cite Michael Liebowitz, psychiatrist and author of the book The Chemistry of Love (1984), as the first proposer of the idea that PEA could be involved in the chemistry of romantic feeling. In his book, Liebowitz seemed to appreciate the intoxication metaphor of love. Indeed, the intense pleasure and euphoria associated with falling in love resemble those of a cocaine or amphetamine trip (Tinklenberg et al., 1978). In both cases, the same ventral dopaminergic areas are consistently activated (Burkett and Young, 2012). Conversely, drug withdrawal as well as emotional rejection cause people to feel depressed. However, the same Dr. Liebowitz acknowledged the fact that, at the time of his writing,

“[…] PEA’s role in our emotional life is at this point only a speculation. What we do have is the observation that drugs that raise PEA levels [i.e., monoamine oxidase inhibitors] are helpful for treating people who habitually become depressed after a romantic disappointment.”

(p. 100)

Thus, it is somehow ironic that he himself ended up starting the track of the Woozle. But this is one common consequence of the way scientific knowledge is received by the general public, which is frequently not at ease with conditionals or hypothetical thinking. Liebowitz is also credited to have popularized the so-called chocolate theory of love, being the ancient Mayan “food of the gods” high in PEA, they say (Emsley, 1999). In reality, PEA levels in chocolate is varying as a function of the processing of cocoa beans, and cheese also contains PEA but nobody associated it with romantic allure, did they? Hypothetically, even a relatively low concentration of 0.02 mg/kg as it was measured in some samples (Ziegleder et al., 1992) could produce an effect on the brain; but even Liebowitz acknowledged in his book that ingested PEA undergoes rapid enzymatic breakdown, preventing significant concentrations from reaching the brain (Wu and Boulton, 1975). It is more likely that supply of its direct precursor, the amino acid l-phenylalanine, could boost PEA concentration in the brain if that should ever be the scope (Sabelli et al., 1986).

Another supporter of the nature of the PEA-love correlation is sex therapist Theresa Crenshaw’s The Alchemy of Love and Lust: How Our Sex Hormones Influence Our Relationships (1996). In her book, published ten years after Liebowitz’s, she explicitly referred to PEA as the “molecule of love”, reinforcing the myth.

“Not surprisingly, high PEA levels have been found in the bloodstream of lovers, probably accounting for the limerance that consumes them both. Chocolate also contains high levels of phenylethylamine.”

(p. 55)

The author didn’t bother to provide any reference for the first statement and seemed to take for granted the chocolate theory of love. The fact that the second statement also originated from word of mouth doesn’t add much to its credibility. Crenshaw went on to highlight the wonderful effects of PEA, ranging from appetite suppressant to “love at first sight” passing from orgasm enhancer.

“That is probably why those intoxicated by romance often comment that they have lost their appetite for everything but each other. PEA’s churning in their bloodstreams. Chemistry at work and at play.”

(p. 55)

These affirmations also lack any bibliography. There are indeed references to food intake suppression by PEA on rats (Dourish and Boulton, 1981; Gilbert and Cooper, 1985) but the loss of appetite in lovers is more likely to result from the interplay of the various substances involved in the above mentioned second stage of romantic love. Crenshaw also gave us a list of more or less accessible tools to “influence PEA” that includes, in addition to chocolate, diet soft drinks (which contains aspartame (PEA is one of the metabolites of artificial sweetener aspartame (Matalon et al., 1987). Actually, Crenshaw did not recommend getting “high” on diet drinks.)), marijuana, (p. 56) and reading romance novels (p. 60). Another unsupported claim linked “abnormally high” PEA levels with ovulation in women.

What PEA Really Does

This is not to say that PEA cannot have a role in the physical and emotional “highs” experienced by lovers. In the brain, PEA is found primarily in the hypothalamus and striatum at low nanomolar concentrations thanks to the high affinity of monoamine oxidase type B (MAOB) that rapidly degrades it combined with the fact that, unlike catecholamines, PEA is not stored in vescicles (Durden and Philips, 1980). It is located in nerve terminals but does not appear to have a role as a primary neurotransmitter (Miller, 2011).

PEA acts in the brain as a neuromodulator at catecholaminergic synapses enhancing dopamine and norepinephrine release (Sabelli and Javaid, 1995). It increases dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (Murata et al., 2009) and dorsal striatum (Ryu et al., 2021) of rats suggesting both rewarding and reinforcing effects that one can easily associate with the “addictive” features of romantic love (Burkett and Young, 2012). Indeed, PEA is self-administered intravenously in the dog as happens with other psychostimulants (e.g., amphetamine) (Risner and Jones, 1977) and it has been shown by Gilbert and Cooper (1983) to induce place preference conditioning in adult rats. At high doses PEA acts as a psychomotor stimulant increasing locomotion and stereotypic behaviours in rodents and monkeys (Ryu et al., 2021). Binding of PEA to the monoamine transporter leads to inhibition of the re-uptake of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine (Irsfeld et al., 2013; Zsilla et al., 2018). Like other trace amines, PEA is reported to increase vascular resistance as a consequence of enhancing norepinephrine activity, in particular by blocking autoinhibitory α2-adrenoceptors (Narang et al., 2014) and via activation of specific receptors belonging to the family of trace amine-associated receptors (Broadley, 2010). The resulting cerebral blood flow reduction is suggested to cause migraine in some individuals (McCulloch and Harper, 1977). There are even reports of hemorrhagic stroke associated with PEA supplements use (Nacca et al., 2020).

Crenshaw (1997) claimed that PEA has been found in abundance in the bloodstream of lovers but, as with some of the other affirmations regarding PEA in her book, no evidence exists supporting the claim to my knowledge. The relatively simple test has never been done, that is comparing PEA levels between lovers and non-lovers or otherwise PEA levels in lovers at baseline and after some love induction. However, measuring PEA/PAA in biological fluids is exactly what a series of studies have done to relate higher PEA metabolism with a range of psychiatric symptoms, founding positive correlations with hypomania and paranoia (Sabelli and Javaid, 1995) that suggests a parallel with the initial euphoria of lovers. These symptoms have been proposed to result from up-regulation of the enzyme that convert phenylalanine to PEA (Buckland et al., 1997). Conversely, PEA levels seems to be reduced in depressed patients. Szabo et al. (2001) conducted a preliminary study comparing urinary concentration of the PEA metabolite phenylacetic acid (PAA) before and after exercise, founding a noteworthy increase of PAA. The authors concluded that the antidepressant effects of exercise could be linked to increased PEA synthesis. Administration of PEA or L-phenylalanine improved mood in depressed patients treated with a selective monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). Indeed, well known antidepressant drugs, from MAOIs to tetrahydrocannabinol, increase brain PEA synthesis and stimulating effect (Sabelli and Javaid, 1995). Interestingly, PEA happens to be one of the main MAOI phenelzine metabolites (Baker et al., 2000).

These evidences has led some authors to postulate the “PEA hypothesis of depression”, that is the idea that PEA, perhaps together with other trace amines, is normally responsible for sustaining mood and physical energy (Branchek and Blackburn, 2003). Assuming this action is true, it should be carefully regulated; in fact, the enzyme MAOB appears to be specifically designed to break down PEA as long as inactivation of MAOB gene in mice increases levels of PEA but not those of other monoamines (Grimsby et al., 1997). After all, lovesickness and breakdown of romantic relationships are frequently the cause of temporary depressive states and anxiety. Indeed, Kosa et al. (2000) found that PEA stimulates the corticotroph axis following daily intraperitoneal administration in male rats. And urinary excretion of PEA was found to be elevated in humans following a parachute jump that was used as a model of stress generator (Paulos and Tessel, 1982). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is instead a condition associated with dopamine and PEA hypometabolism (Branchek and Blackburn, 2003); therefore it could be hypothesized that falling in love attenuates symptoms in people who suffer from ADHD. When the attraction phase is over, they would get more dissatisfied than healthy people; that could explain why adolescents with ADHD reported having more romantic partners than their peers (Rokeach and Wiener, 2018).

Conclusions

Our conclusion is that the evidence supporting the idea of PEA as a “love molecule” are week if not non-existent. The concept appears to be an extrapolation from researches that linked PEA with improving mood, which is in fact one of the consequences of falling in love, combined with the fact that it is found in chocolate, a food popularly associated with lovers and considered an aphrodisiac. It should also be remembered the structural affinity between PEA and amphetamine and the fact that many substituted phenylethylamines act as psychoactive drugs, ranging from stimulants to entactogens (Dean et al., 2013). Thus, it would seem perfectly plausible to ascribe to this endogenous molecule such a vital role in the human affairs. However, instead of keep repeating the old saying we should begin to collect some evidence for the statement.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Wikipedia anonymous contributor whose passionate and blind crusade in favor of the “love molecule” theory on the Italian PEA entry initially put me on the track of the Woozle.

References

- Acevedo, B.P.; Aron, A.; Fisher, H.E.; Brown, L.L. Neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2012, 7, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, G.B.; Coutts, R.T.; Greenshaw, A.J. Neurochemical and metabolic aspects of antidepressants: an overview. . 2000, 25, 481–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bernaerts, S.; Prinsen, J.; Berra, E.; Bosmans, G.; Steyaert, J.; Alaerts, K. Long-term oxytocin administration enhances the experience of attachment. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 78, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branchek, T.; Blackburn, T.P. Trace amine receptors as targets for novel therapeutics: legend, myth and fact. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2003, 3, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadley, K.J. The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 125, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckland, P.R.; Marshall, R.; Watkins, P.; McGuffin, P. Does phenylethylamine have a role in schizophrenia?: LSD and PCP up-regulate aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase mRNA levels. Mol. Brain Res. 1997, 49, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkett, J.P.; Young, L.J. The behavioral, anatomical and pharmacological parallels between social attachment, love and addiction. Psychopharmacology 2012, 224, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, C.S.; Ph. D.; G.Welch, M.; J.Ludwig, R. The Role of Oxytocin and Vasopressin in Attachment. Psychodyn. Psychiatry 2017, 45, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crenshaw, T. (1997). The alchemy of love and lust. Pocket Books.

- Dean, B.V.; Stellpflug, S.J.; Burnett, A.M.; Engebretsen, K.M. 2C or Not 2C: Phenethylamine Designer Drug Review. J. Med Toxicol. 2013, 9, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourish, C.T.; Boulton, A.A. The effects of acute and chronic administration of β-phenylethylamine on food intake and body weight in rats. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology 1981, 5, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, D.A.; Philips, S.R. Kinetic Measurements of the Turnover Rates of Phenylethylamine and Tryptamine In Vivo in the Rat Brain. J. Neurochem. 1980, 34, 1725–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emsley, J. (1999a). Molecules at an exhibition: Portraits of intriguing materials in everyday life. Oxford University Press.

- Feygin, D.L.; Swain, J.E.; Leckman, J.F. The normalcy of neurosis: Evolutionary origins of obsessive–compulsive disorder and related behaviors. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 30, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, H.E. Lust, attraction, and attachment in mammalian reproduction. Hum. Nat. 1998, 9, 23–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flight, T. (2018, December 27). 20 downright bizarre details about the history of chocolate that we love to sink our teeth into. History Collection. https://historycollection.com/20-downright-bizarre-details-about-the-history-of-chocolate-that-we-love-to-sink-our-teeth-into/.

- Gilbert, D.; Cooper, S.J. β-phenylethylamine-, D-amphetamine- and L-amphetamine-induced place preference conditioning in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1983, 95, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, D. B. , & Cooper, S. J. (1985). β-Phenylethylamine and Amphetamine Compared in Tests of Anorexia and Place-Preference Conditioning. In A. A. Boulton, L. Maitre, P. R. Bieck, & P. Riederer (Eds.), Neuropsychopharmacology of the Trace Amines: Experimental and Clinical Aspects (pp. 187–193). Humana Press. [CrossRef]

- Grimsby, J.; Toth, M.; Chen, K.; Kumazawa, T.; Klaidman, L.; Adams, J.D.; Karoum, F.; Gal, J.; Shih, J.C. Increased stress response and β–phenylethylamine in MAOB–deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 1997, 17, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.D.; Johnson, P.E.; Herbel, J.; Mullen, L.K. Effects of dietary zinc depletion on seminal volume and zinc loss, serum testosterone concentrations, and sperm morphology in young men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1992, 56, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irsfeld, M. , Spadafore, M., & Prüß, B. M. (2013). Β-phenylethylamine, a small molecule with a large impact. WebmedCentral, 4(9).

- Koob, G. F. , Arends, M. A., McCracken, M. L., Le Moal, M (2020). Psychostimulants. Academic Press.

- Kosa, E.; Marcilhac-Flouriot, A.; Fache, M.-P.; Siaud, P. Effects of β-phenylethylamine on the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis in the male rat. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2000, 67, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langeslag, S.J.E.; van der Veen, F.M.; Fekkes, D. Blood Levels of Serotonin Are Differentially Affected by Romantic Love in Men and Women. J. Psychophysiol. 2012, 26, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonti, M.; Casu, L. Ethnopharmacology of Love. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebowitz, M. R. (1984). The chemistry of love. Berkley Publishing Books.

- Marazziti, D.; Akiskal, H.S.; Rossi, A.; Cassano, G.B. Alteration of the platelet serotonin transporter in romantic love. Psychol. Med. 1999, 29, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marazziti, D.; Canale, D. Hormonal changes when falling in love. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004, 29, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matalon, R.; Michals, K.; Sullivan, D.; Levy, P. Aspartame intake and its effect on phenylalanine (phe) and phe metabolites. Pediatr. Res. 1987, 21, 344A–344A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCULLOCH, J.; Harper, A.M. Phenylethylamine and cerebral blood flow. Neurology 1977, 27, 817–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLauchlan, J.; Thompson, E.M.; Ferrão, Y.A.; Miguel, E.C.; Albertella, L.; Marazziti, D.; Fontenelle, L.F. The price of love: an investigation into the relationship between romantic love and the expression of obsessive–compulsive disorder. CNS Spectrums 2022, 27, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, G.M. The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity. J. Neurochem. 2011, 116, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, M.; Katagiri, N.; Ishida, K.; Abe, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Utsunomiya, I.; Hoshi, K.; Miyamoto, K.-I.; Taguchi, K. Effect of β-phenylethylamine on extracellular concentrations of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. 2009, 1269, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacca, N.; Schult, R.F.; Li, L.; Spink, D.C.; Ginsberg, G.; Navarette, K.; Marraffa, J. Kratom Adulterated with Phenylethylamine and Associated Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Linking Toxicologists and Public Health Officials to Identify Dangerous Adulterants. J. Med Toxicol. 2020, 16, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, D.; Kerr, P.M.; Lunn, S.E.; Beaudry, R.; Sigurdson, J.; Lalies, M.D.; Hudson, A.L.; Light, P.E.; Holt, A.; Plane, F. Modulation of Resistance Artery Tone by the Trace Amine β-Phenylethylamine: Dual Indirect Sympathomimetic and α1-Adrenoceptor Blocking Actions. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2014, 351, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulos, M.A.; Tessel, R.E. Excretion of β-Phenethylamine Is Elevated in Humans After Profound Stress. Science 1982, 215, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risner, M.E.; Jones, B. Characteristics of β-phenethylamine self-administration by dog. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1977, 6, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeach, A.; Wiener, J. The Romantic Relationships of Adolescents With ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2018, 22, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, B. Religion and the Churches. Unpopular Review 1916, 5, 392–409. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, I.S.; Kim, O.-H.; Kim, J.S.; Sohn, S.; Choe, E.S.; Lim, R.-N.; Kim, T.W.; Seo, J.-W.; Jang, E.Y. Effects of β-Phenylethylamine on Psychomotor, Rewarding, and Reinforcing Behaviors and Affective State: The Role of Dopamine D1 Receptors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabelli, H.; Fawcett, J.; Gusovsky, F.; Javaid, J.; Wynn, P.; Edwards, J.; Jeffriess, H.; Kravitz, H. Clinical-studies on the phenylethylamine hypothesis of affective-disorder - urine and blood phenylacetic acid and phenylalanine dietary-supplements. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1986, 47, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sabelli, H.C.; I Javaid, J. Phenylethylamine modulation of affect: therapeutic and diagnostic implications. J. Neuropsychiatry 1995, 7, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, B.B. Sex hormones and psychological functioning in postmenopausal women. Exp. Gerontol. 1994, 29, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, A.; Billett, E.; Turner, J. Phenylethylamine, a possible link to the antidepressant effects of exercise? Br. J. Sports Med. 2001, 35, 342–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Mizuno, K.; Sasaki, A.T.; Wada, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Ishii, A.; Tajima, K.; Tsuyuguchi, N.; Watanabe, K.; Zeki, S.; et al. Imaging the passionate stage of romantic love by dopamine dynamics. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 191–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinklenberg, J.R.; Gillin, J.C.; Murphy, G.M.; Staub, R.; Wyatt, R.J. The effects of phenylethylamine in rhesus monkeys. Am. J. Psychiatry 1978, 135, 576–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia contributors. (2023, January 8). Woozle effect. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Woozle_effect&oldid=1132276532.

- Wu, P.H.; Boulton, A.A. Metabolism, Distribution, and Disappearance of Infected β-Phenylethylamine in the Rat. Can. J. Biochem. 1975, 53, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, T.D. The search for human pheromones: the lost decades and the necessity of returning to first principles. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20142994–20142994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegleder, G.; Stojacic, E.; Stumpf, B. Occurrence of 2-phenylethylamine and its derivatives in cocoas and chocolates. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 1992, 195, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsilla, G.; Hegyi, D.E.; Baranyi, M.; Vizi, E.S. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine, mephedrone, and β- phenylethylamine release dopamine from the cytoplasm by means of transporters and keep the concentration high and constant by blocking reuptake. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 837, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).