Introduction

Due to the widespread use of various types of air engines globally, thermodynamic and exergy analysis has become a critical issue[

1]. Developing these engines based on diverse needs and applications, designing more efficient engines, and optimizing existing engines are all methods rooted in thermodynamic and exergy analysis. In the new century, air transport plays a fundamental role in the transportation of passengers and goods[

2]. With more than two and a half billion people traveling safely around the world each year, there are an average of 22,000 commercial airliners in operation[

3].

Passenger numbers worldwide are projected to grow by an average of 2.9% annually. However, this growth in air transport also exacerbates environmental pollution problems. Jet engines, as significant polluters, emit gaseous pollutants such as CO2, NOx, and other known greenhouse gases, which contribute to the formation of contrails. According to a comprehensive assessment by ICAO [

4] published in 2019, the total CO2 emissions from aviation account for approximately 3% of the world's greenhouse gas emissions[

5]. While air transportation has a significant environmental impact, it is not inherently detrimental. The environmental effects can be significantly mitigated by improving the efficiency of engine components[

6]. More effective and efficient energy use reduces pollutant emissions, making energy consumption a crucial factor in balancing economic and social development with environmental protection. To achieve sustainable development, more efficient and optimal energy systems must be developed. Engineering companies often use energy analysis to evaluate and study energy systems, and exergy analysis is increasingly recognized for its effectiveness in assessing system efficiency, sometimes proving more informative than energy analysis[

7].

Exergy analysis is a method that employs the principles of conservation of mass, conservation of energy, and the second law of thermodynamics to analyze, design, and improve systems. This powerful tool enables more efficient and optimal use of energy resources by identifying the locations, types, and amounts of exergy production and losses[

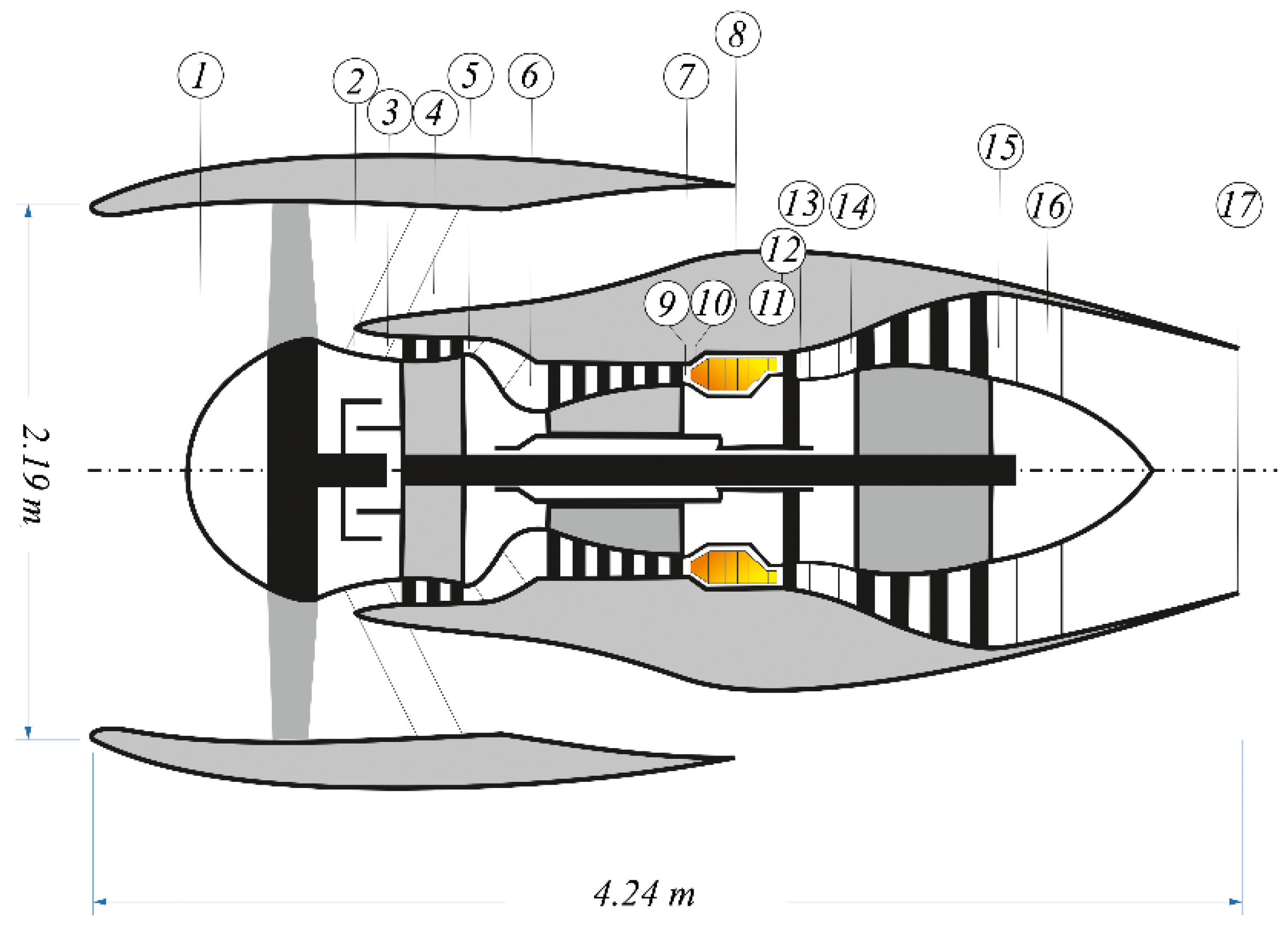

8]. The primary aim of this paper is to conduct a thermodynamic and exergy analysis of a turbofan engine, which is the most commonly used engine in commercial aviation. Utilizing the exergy approach allows for a deeper understanding of exergy destruction and inefficiencies within various engine components. The exergy evaluation of the engine is performed for a specific operating condition in the cruise phase. Due to product confidentiality, engine manufacturers typically do not disclose detailed operational information beyond basic specifications. Consequently, a mathematical model of the engine is developed to simulate cruise operational data for use in the exergy analysis[

9]. In recent years, researchers and engineers have increasingly employed exergy analysis to assess system performance.

Ebrahim Lalias[

10] presented an exergy analysis of a turbofan engine with a low bypass ratio during the take-off phase. The JT8D engine, a low bypass ratio turbofan, is installed on aircraft such as the 737-100, DC9, and MD80. His analysis identified the combustion chamber and turbine as the components with the highest irreversibility and exergy loss. Tatiana and colleagues[

11] conducted an exergy analysis on a gas turbine system, highlighting the importance of evaluating the thermodynamic performance of system components to determine which ones cause the most exergy destruction. Ahmad al-Khalid Altai[

12] performed an exergy analysis and parametric study of a gas power plant in response to high energy demand in Saudi Arabia. The results of his evaluation are as follows:

Increasing energy efficiency leads to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in a lower environmental impact.

The combustion chamber exhibits the highest exergy destruction, followed by the turbine. Additionally, increasing exergy efficiency reduces greenhouse gas emissions and environmental impacts.

Yasin et al. [

13] performed an exergy analysis of a turbofan engine for an aircraft during a mission. Their study focused on the Rolls-Royce AE3007H engine; a high bypass ratio turbofan engine developed for the Cessna Citation X. The results indicated that the combustion chamber and afterburner exhibit the most significant exergy destruction within the engine. While the study was thorough, there are potential inconsistencies in the engine modeling data, as the modeling approach by Yasin et al. is not fully detailed. The only reference provided compares a real code with modeling software. Additionally, some critical thermodynamic parameters used in the exergy analysis, such as specific heat at constant pressure and enthalpy, may have been calculated using different formulas than those used in engine modeling.

In this paper, the exergy destruction and efficiency of the CF6-80A and CFM56 engines are analyzed and investigated. The study aims to improve the parameters affecting the engines' exergy analysis using fuzzy logic and optimize these parameters with meta-heuristic optimizers such as the artificial bee colony (ABC) and particle swarm optimization (PSO) to achieve optimal values.

Thermodynamic Governing Equations

For the thermodynamic analysis of these engines, previously established equations are utilized. The exergy analysis employs equations of energy conservation, exergy conservation, and mass conservation for each component of the turbofan engines[

16,

17].

Inlet

At the inlet, the pressure (P1) and temperature (T1) increase, and the mass flow rate (ṁ) is derived from the engine specifications provided by the manufacturer.

In Equation (1) and (2), () and () are the static temperature and pressure respectively, which are determined and related to the flight altitude. is the flight Mach number which is determined according to the technical specifications of the engine in the cruise phase.

Fan

After the engine inlet, the air flow encounters the fan stage. Upon passing through the fan, the flow is divided into two parts: one part enters the engine core, while the other part bypasses the core. bypass mass flow rate denotes as

.Given the high bypass ratio of this engine, it is evident that the mass flow rate entering the engine core is significantly less than the mass flow rate passing through the bypass. The values of

and

are calculated using Equation (4) and (5).

Since the fan increases the air pressure, the pressure values at the motor core inlet () and the bypass inlet pressure () are determined using Equations (6) and (7).

Equations (6) and (7) involve the fan pressure ratio, and , each with a value of 2.6. The isentropic efficiency of the fan () and ()is calculated using Equations (8) and (9) in this section of the engine.

In the next step, Equations (10) and (11) are used to calculate the temperature at the fan inlet () and the engine bypass temperature ().

Bypass

In this part of the engine, the temperature of the flow is assumed to be nearly constant, with only a slight drop in pressure due to the existing expansion. The temperature (

) and pressure (

) in this section are derived from the following equations.

In Equation (13), the bypass expansion ratio, denoted as , is assumed to be 0.91.

Low Pressure Compressor:

In this segment of the engine, the second stage of compression takes place. It should be noted that variations in temperature (), pressure (), or airflow rate in the duct connecting the fan outlet to the low-pressure compressor inlet are disregarded. Consequently, the following is observed:

At the outlet of the low-pressure compressor, the outlet pressure (), outlet temperature (), and mass flow rate () can be calculated using equations (18) to (20):

In Equation (20),

, the pressure ratio of the low-pressure compressor, is 5.56, as specified by the manufacturer. The work produced by the low-pressure compressor (

) will be calculated using Equation (21).

High Pressure Compressor

In this section of the engine, the third and final stage of compression takes place before the flow enters the combustion chamber. The temperature and pressure between the output of the low-pressure compressor and the input of the high-pressure compressor undergo minimal changes, which are considered constant. At the input of the compressor, the pressure (

), temperature (

), and mass flow rate

) can be obtained from Equations (22) to (24):

At the output of the high-pressure compressor, the output pressure (

), output temperature (

), and mass flow rate

can be calculated using equations (25) to (27):

In Equation (27),

, the pressure ratio of the high-pressure compressor, is set at 11, as specified by the manufacturer. The work produced by the high-pressure compressor

is calculated using Equation (28).

Combustion Chamber

The temperature, pressure, and mass flow rate of the flow between the high-pressure compressor and the inlet of the combustion chamber undergo slight changes, which can be considered negligible. Consequently, the inlet pressure (

), inlet temperature (

), and inlet mass flow rate

of the combustion chamber are calculated using equations (29) to (31):

In this section of the engine, the combustion process involves the injection of fuel into the combustion chamber. The fuel flow mass rate

and the total flow mass rate

are calculated using equations (32) and (33):

In Equation (32),

represents the ratio of fuel to air, which can be calculated using Equation (34).

The output pressure (

) and the output temperature (

) in the combustion chamber can be calculated using Equations (35) and (36), with the output temperature of the combustion chamber determined based on information provided by the engine manufacturer.

In Equation (35), represents the design efficiency of the combustion chamber, typically assumed to be 90% for most turbofan engines.

High-Pressure Turbine

In the high-pressure turbine section, negligible variations occur in the temperature (

), pressure (

), and mass flow rate (

) of the fluid stream between the exit of the combustion chamber and the inlet of the high-pressure turbine. Thus, for practical purposes, these alterations can be disregarded, leading to the following assumption:

In this segment of the engine, the first stage of gas expansion occurs. As conventionally understood, the compressor performs work on the fluid. However, in contrast, the turbine operates inversely, extracting work from the fluid to drive both the fan and the compressor. The initial task entails computing the power generated by the high-pressure compressor (

). Thus, following Equation (40), the power produced by the high-pressure compressor is determined.

In Equation (40),

representing the efficiency of the high-pressure compressor, assumed to be 95%. This value is deemed reasonable and acceptable within the scope of this analysis. Additionally, the output temperature of the high-pressure turbine (

) can be derived from Equation (41).

To compute the pressure, initially, an acceptable value for the high-pressure turbine expansion ratio (

) is assumed, set at 5. Subsequently, the pressure value at the outlet of the high-pressure turbine (

) can be determined. Moreover, the mass flow rate (

) of the flow remains constant, yielding:

In the low-pressure turbine segment, minor variations occur in the temperature (

), pressure (

), and mass flow rate (

) of the fluid stream between the exit of the combustion chamber and the inlet of the low-pressure turbine. These variations are negligible and can be disregarded, resulting in:

In this section of the engine, the second stage of gas expansion occurs. By extracting work from the fluid and driving this segment of the engine, it facilitates the rotation of the low-pressure section of the engine and the N1 shaft. The initial step involves computing the power generated by the low-pressure turbine (

), akin to the previous section. Thus, in accordance with Equation (47), the following expression is obtained:

In Equation (47), (

) representing the efficiency of the low-pressure compressor, is assumed to be 95%, a value deemed reasonable and acceptable. The values for the output pressure (

) and output temperature (

) of the low-pressure turbine can be calculated utilizing Equation (49) and (50), respectively. Additionally, the mass flow rate (

) of the flow remains constant, yielding:

In relation (49), representing the low-pressure turbine expansion ratio, is assumed to be 4, a value considered promising for the analysis.

Nozzle

In this section of the engine, where the final stage of expansion occurs, the mass flow rate (

), pressure (

), and temperature (

) of the flow are determined using relations (51) to (53).

In relation (53), denoting the nozzle efficiency, is specified as 92% according to the manufacturer's information for this engine.

specific Fuel Consumption and Thrust

To compute these values, it is imperative to ascertain both the hot thrust of the nozzle (

) and the cold thrust of the nozzle (

). This can be achieved through the following calculations:

In Equation (54),

represents the output Mach number from the engine core.

In Equation (55),

denotes the output temperature from the engine core.

In Equation (56),

represents the output pressure from the engine core.

In Equation (57),

denotes the speed of sound in the engine core.

In Equation (58),

represents the outlet speed in the engine core.

Equations (54) to (59) can be utilized for calculating the hot thrust. For the cold thrust, a similar methodology will be applied, resulting in:

In Equation (60),

represents the Mach number in the exit from the bypass.

In Equation (61),

denotes the exit temperature of the bypass.

In Equation (62),

represents the output pressure from the bypass.

In Equation (63), a8 denotes the speed of sound of the bypass.

In Equation (64),

represents the exit velocity of the bypass.

To calculate the net thrust (

) and specific thrust fuel consumption (

), the following formulas are utilized:

The thrust magnitude and specific thrust fuel consumption are determined as follows:

Exergy Governing Equations

Utilizing the principles of conservation of mass, energy, and exergy, equations (68) to (70) governing exergy equations for each component of the engine can be derived and are as follows[

18]:

Subscripts in input, output, and Dest. represent input, output, and destruction, respectively. To conduct an exergetic assessment, performance parameters must be considered to evaluate an energy system and its components. Exergy efficiency encompasses the following factors: recovery potential, relative rate of exergy destruction, fuel reduction rate, and productivity deficit.

Exergy efficiency (

) is defined as the ratio between the exergy rate of the product (

) and the fuel (

). The exergy of the product signifies the desired outcome produced, while the exergy of the fuel represents the resources utilized to generate the product. Their relationship is expressed as follows:

The subsequent parameter is the improvement potential

, defined as the quantity of exergy destruction within the system. It quantifies the scope available for enhancement and reduction of irreversibility, and it is derived from Equation (72):

The subsequent parameter is the relative exergy destruction

, defined as the ratio of the exergy destruction rate of a component to the total exergy destruction rate of a system. This parameter illustrates the percentage of exergy destruction within the system, and it is derived from Equation (73):

Another critical parameter is the fuel depletion rate (

), defined as the ratio of the exergy destruction rate to the total exergy rate of the fuel entering the system. It is derived from equation (74):

Another parameter worth noting is the productivity lack rate (

), defined as the ratio of the exergy destruction rate to the total exergetic product rate in the system. This parameter quantifies the loss of exergy potential in the product resulting from exergy destruction. It is obtained from Equation (75):

In the subsequent sections, we will delve into the exergy relations for each component of the engine, which have been deduced utilizing the stability Equation (72) to (74), and employed for the purpose of this analysis and scrutiny:

Fan

Figure 2.

Exergy Flows in the Fan.

Figure 2.

Exergy Flows in the Fan.

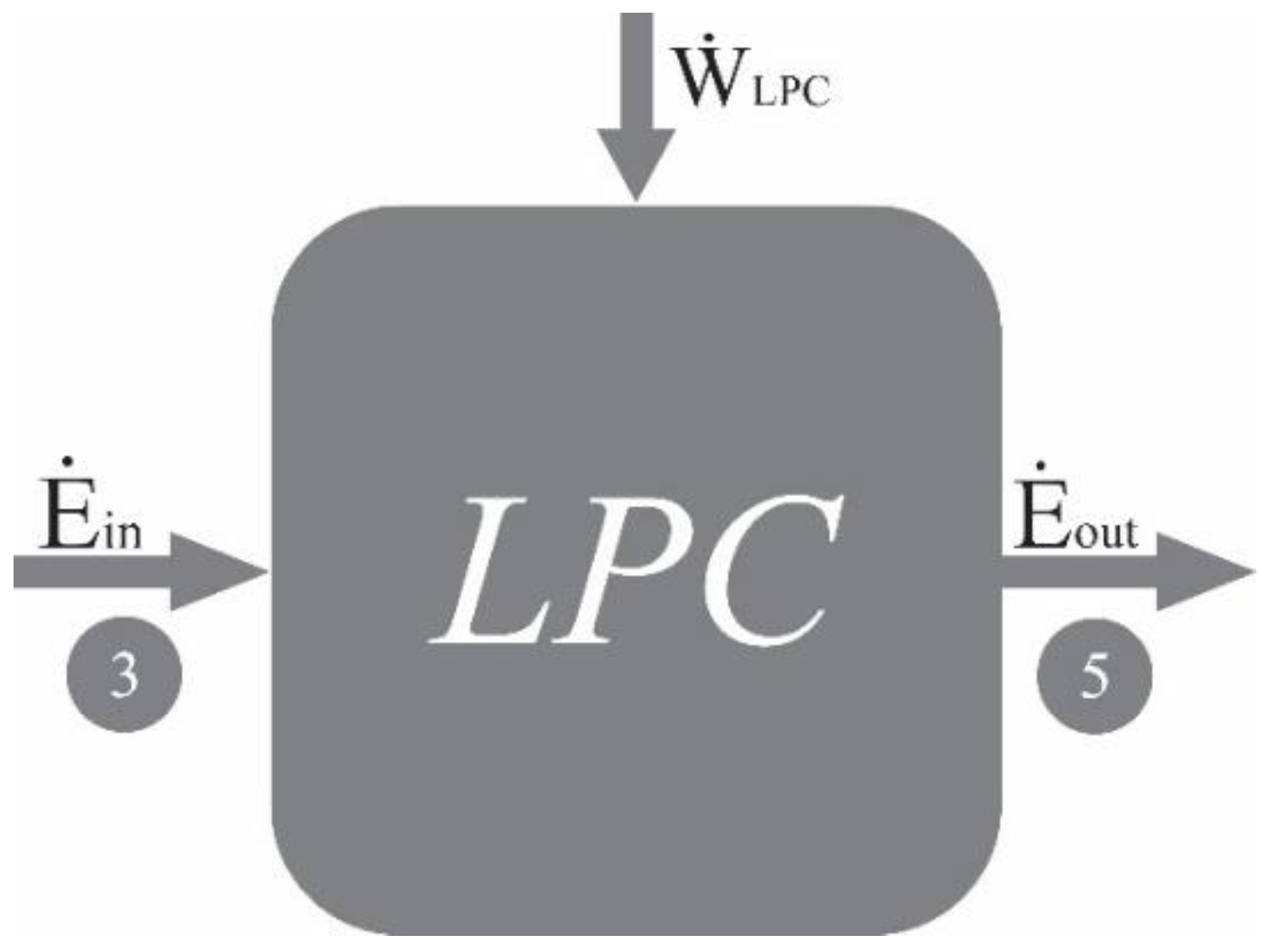

Low Pressure Compressor (LPC)

Figure 3.

Exergy flows in the low-pressure compressor.

Figure 3.

Exergy flows in the low-pressure compressor.

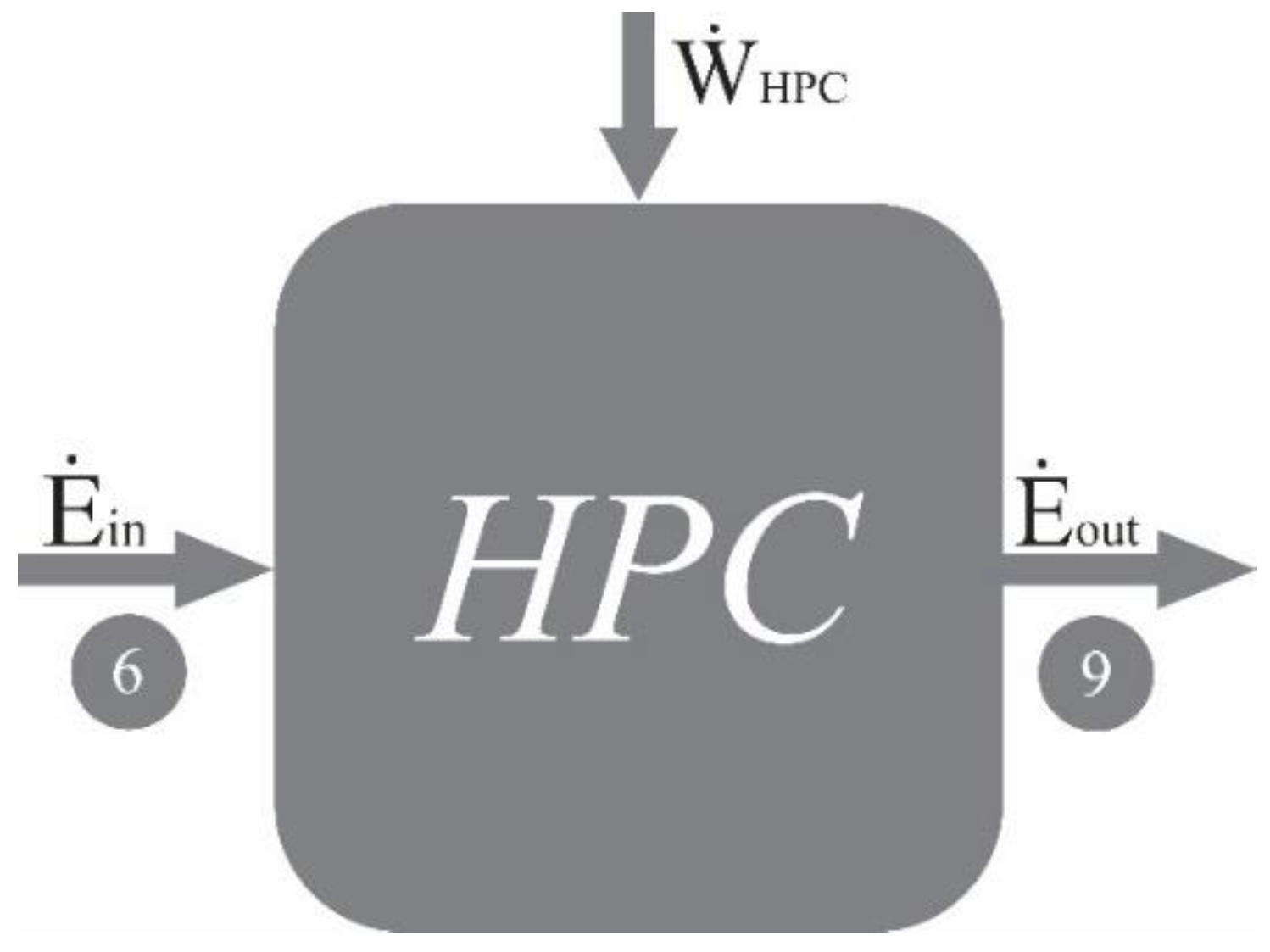

High Pressure Compressor (HPC)

Figure 4.

Exergy Flows in the High-Pressure Compressor.

Figure 4.

Exergy Flows in the High-Pressure Compressor.

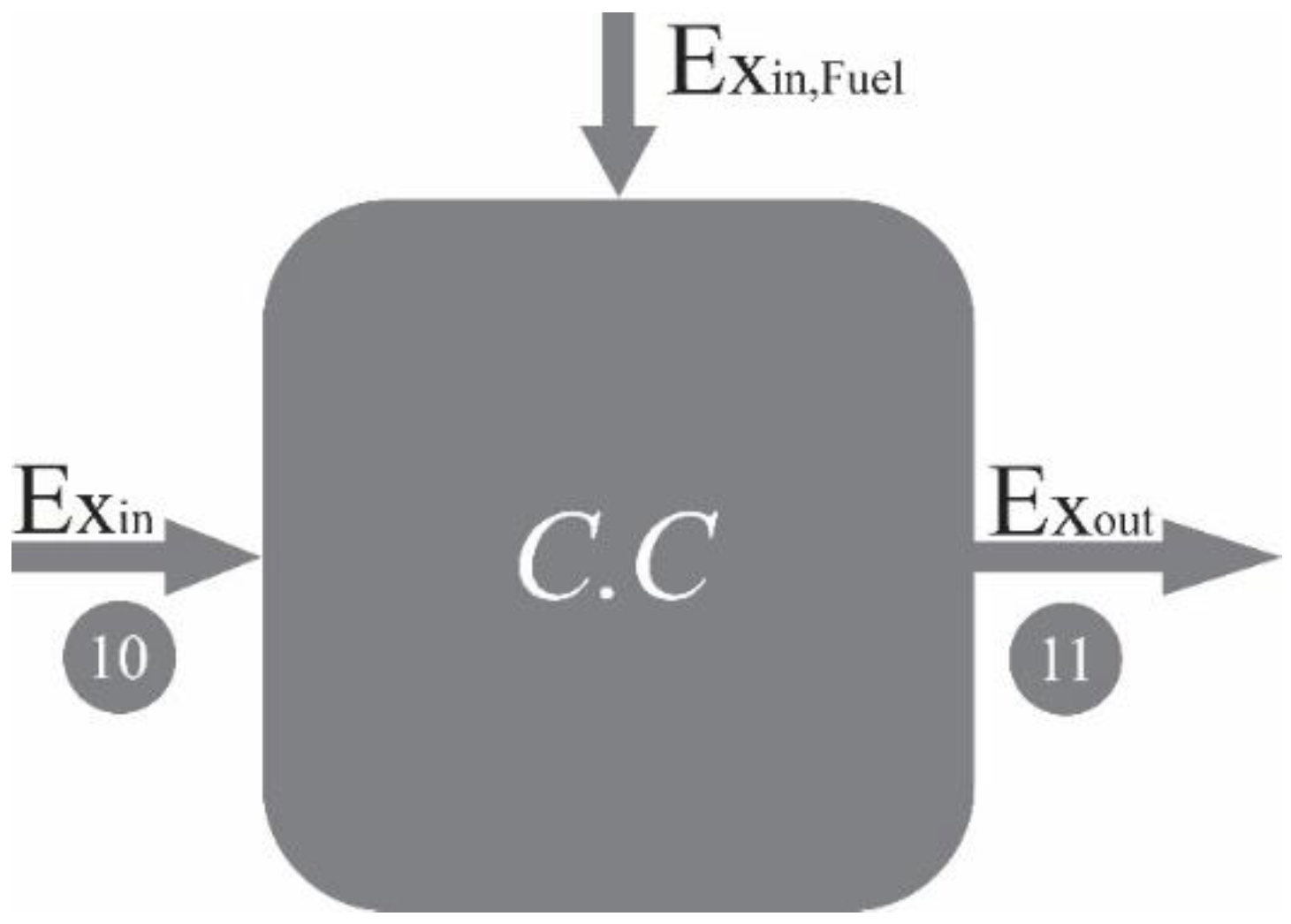

Combustion Chamber (CC)

Figure 5.

Exergy Flows in the Combustion Chamber.

Figure 5.

Exergy Flows in the Combustion Chamber.

In Equation (108),

represents the exergy value of the fuel, which can be computed using the following relation. In Equation (112),

denotes the ratio of the exergy of the fuel to the low heating value of the fuel, obtained through Equation (109).

The low heating value () represents the low heating value of the fuel. For most liquid and gaseous fuels with compositions such as Cα Hβ Nγ Oδ, the value of is typically close to 1. The fuel utilized in this engine has the chemical formula C12 H23 and a low calorific value of 42800 kJ/kg.

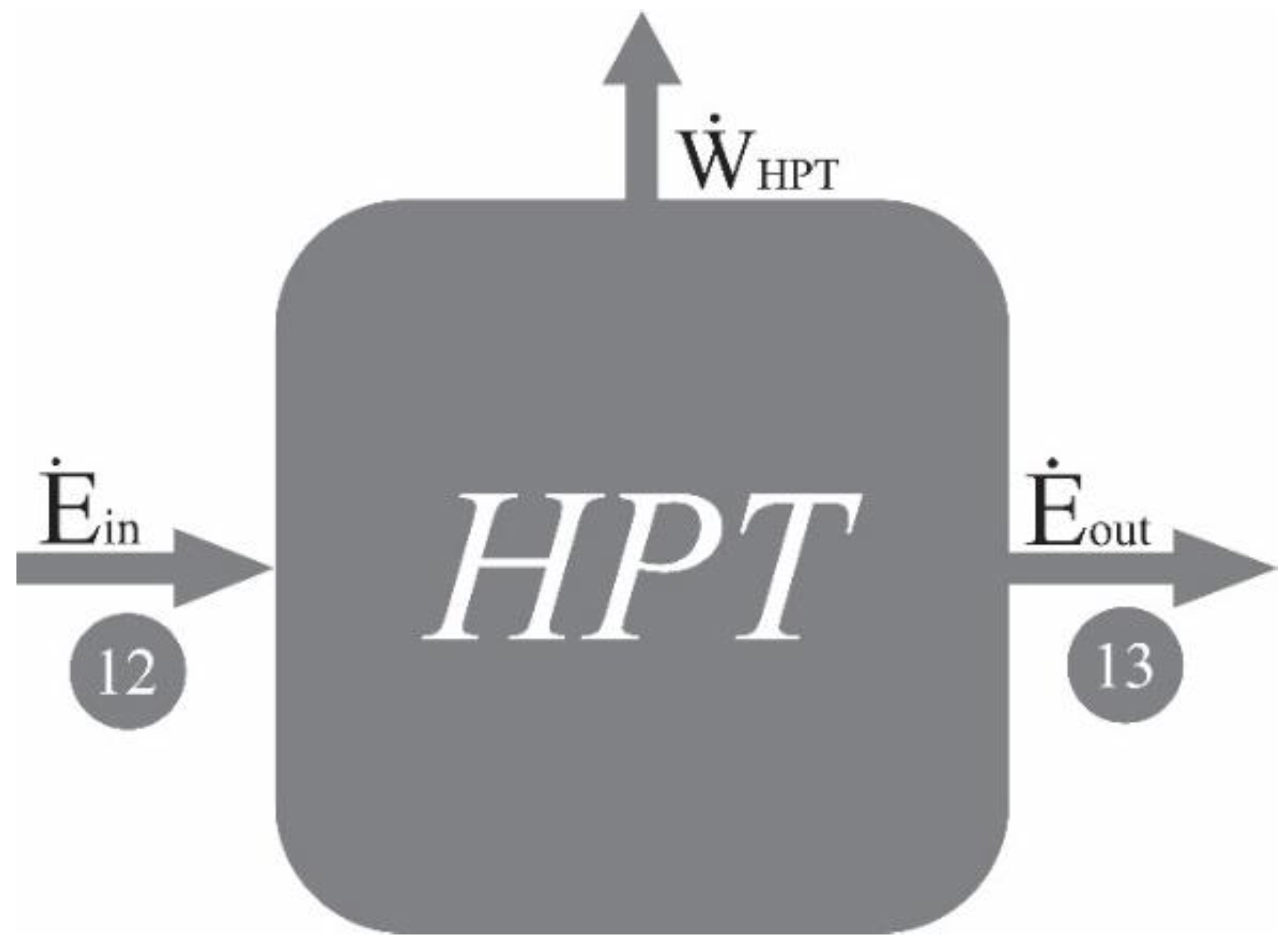

High Pressure Turbine (HPT)

Figure 6.

Exergy Flows in the High-Pressure Turbine.

Figure 6.

Exergy Flows in the High-Pressure Turbine.

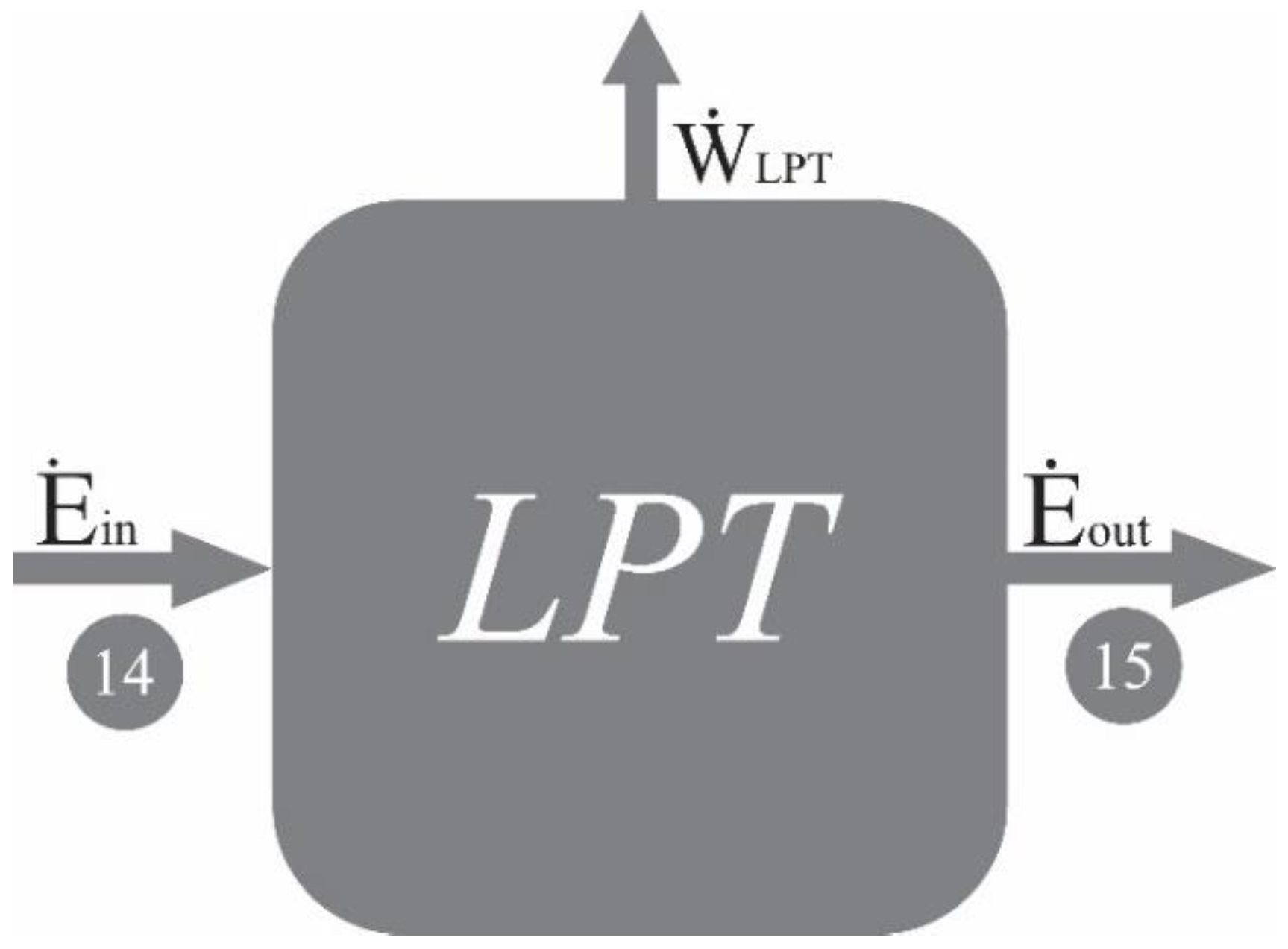

Low Pressure Turbine (LPT)

Figure 7.

Exergy Flows in the Low-Pressure Turbine.

Figure 7.

Exergy Flows in the Low-Pressure Turbine.

Exergy Analysis Results

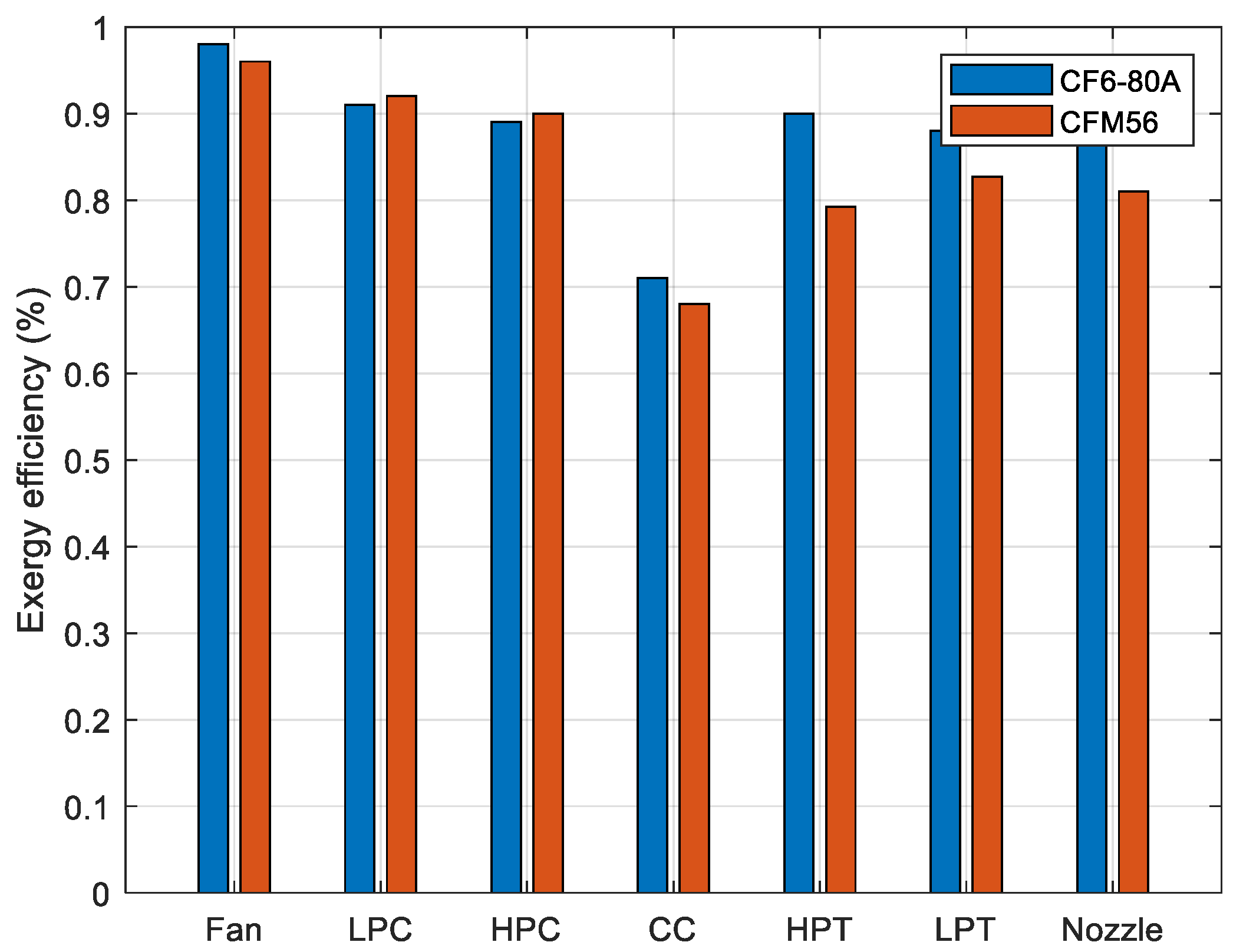

Exergy efficiency results are depicted in

Figure 8 for each component of the engines. The combustion chamber exhibits the lowest exergy efficiency, while other components demonstrate relatively high exergy efficiency, exceeding 90%, for both engines. Specifically, for the CF6-80A engine, the exergy efficiencies are as follows: fan 95.11%, low-pressure compressor 90.92%, high-pressure compressor 89.42%, combustor 71.75%, high-pressure turbine 90.75%, low-pressure turbine 88.22%, and nozzle 93.12%. For the CFM56 engine, the corresponding exergy efficiencies are: fan 92.10%, low-pressure compressor 91.52%, high-pressure compressor 90.01%, combustor 68.01%, high-pressure turbine 79.71%, low-pressure turbine 82.12%, and nozzle 81.02%. These results clearly indicate that the CF6-80A engine exhibits superior exergy efficiency compared to the CFM56.

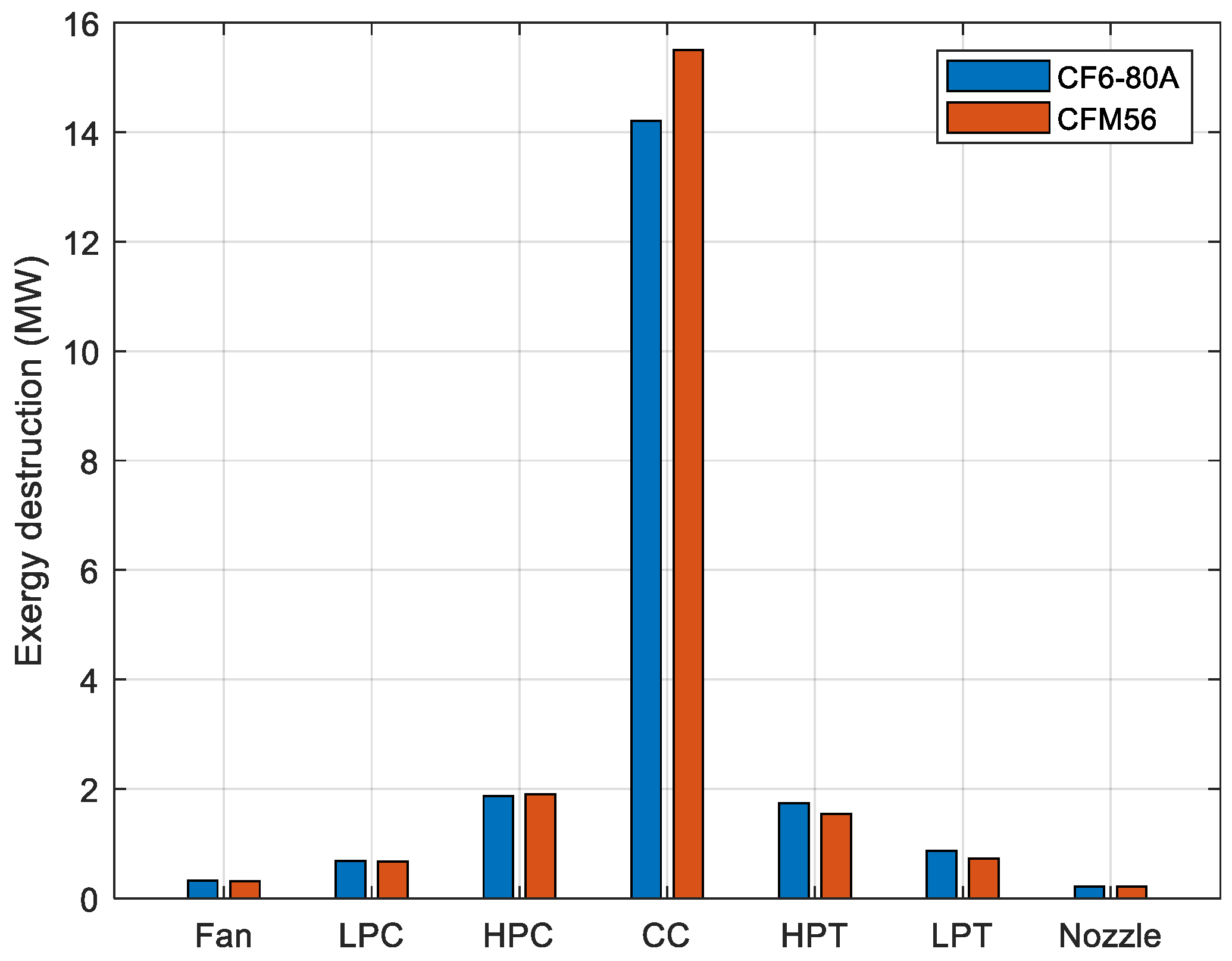

Figure 9 illustrates the exergy destruction in each component of the engine. As anticipated, the combustion chamber exhibits the highest exergy destruction due to the presence of irreversibility’s. For the CF6-80A engine, the exergy destruction values are as follows: fan 0.24 MW, low-pressure compressor 0.57 MW, high-pressure compressor 1.92 MW, combustor 14.21 MW, high-pressure turbine 1.86 MW, low-pressure turbine 0.53 MW, and nozzle 0.152 MW. Conversely, for the CFM56 engine, the corresponding exergy destruction values are: fan 0.238 MW, low-pressure compressor 0.565 MW, high-pressure compressor 1.912 MW, combustor 15.02 MW, high-pressure turbine 1.78 MW, low-pressure turbine 0.481 MW, and nozzle 0.151 MW. These results clearly indicate that the CF6-80A engine experiences lower exergy destruction compared to the CFM56.

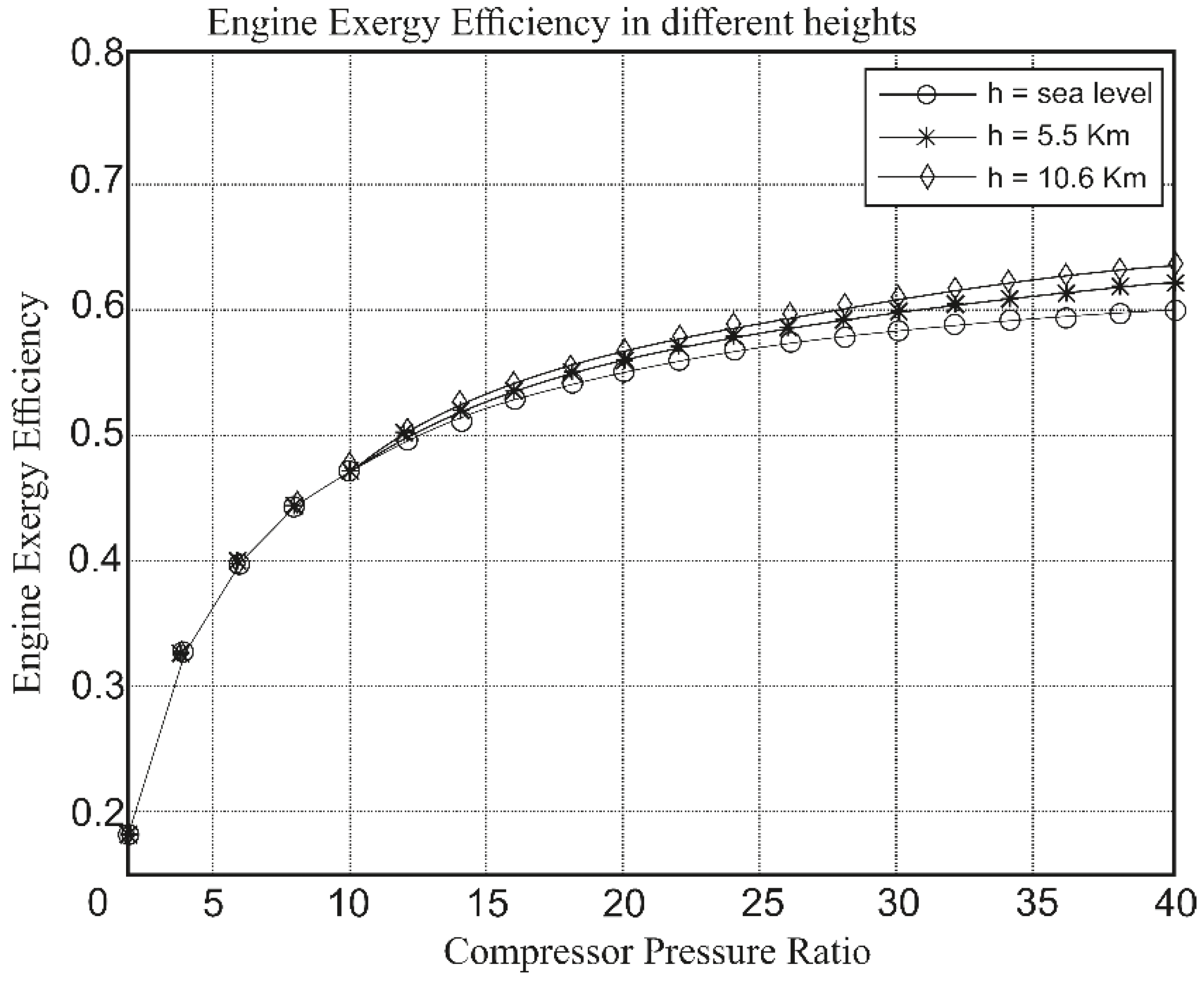

Figure 10 illustrates the changes in exergy efficiency for this analysis concerning variations in flight altitude and the working pressure ratio of the compressors. It is evident that the engine's exergy efficiency increases with an increase in flight altitude. The optimal condition depicted in this diagram is flight at an altitude of 10.6 kilometers with a compressor pressure ratio of 40.

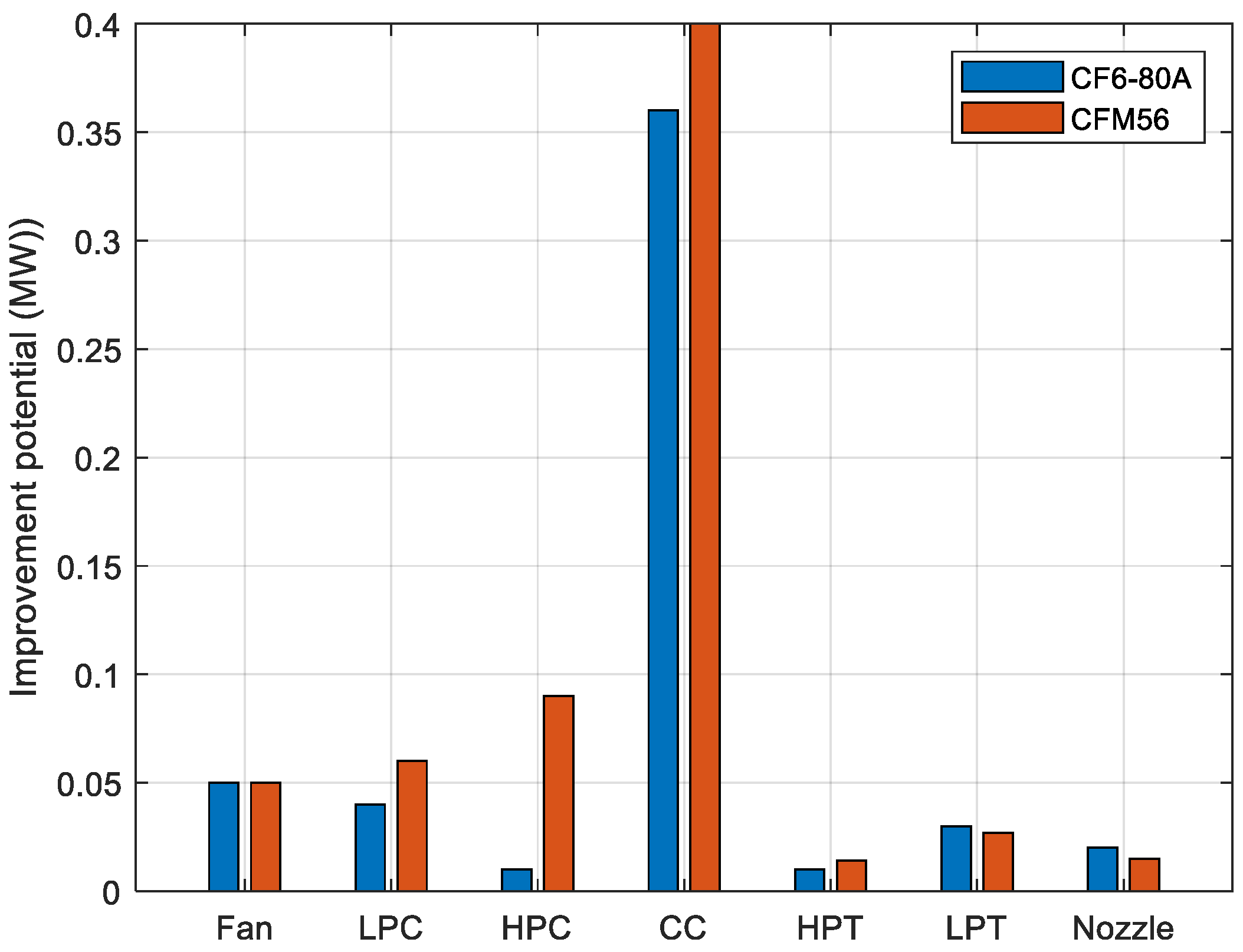

Figure 11 presents the improvement potential in each component of the engine. The combustion chamber emerges as the most critical component for improvement. The improvement potential for the CF6-80A engine is as follows: fan 0.0512 MW, low-pressure compressor 0.0481 MW, high-pressure compressor 0.0235 MW, combustor 0.368 MW, high-pressure turbine 0.0289 MW, low-pressure turbine 0.0389 MW, and nozzle 0.298 MW. For the CFM56 engine, the corresponding improvement potential values are: fan 0.0512 MW, low-pressure compressor 0.0612 MW, high-pressure compressor 0.911 MW, combustor 0.40 MW, high-pressure turbine 0.0258 MW, low-pressure turbine 0.03521 MW, and nozzle 0.0257 MW. These results indicate that the CF6-80A engine exhibits better improvement potential compared to the CFM56.

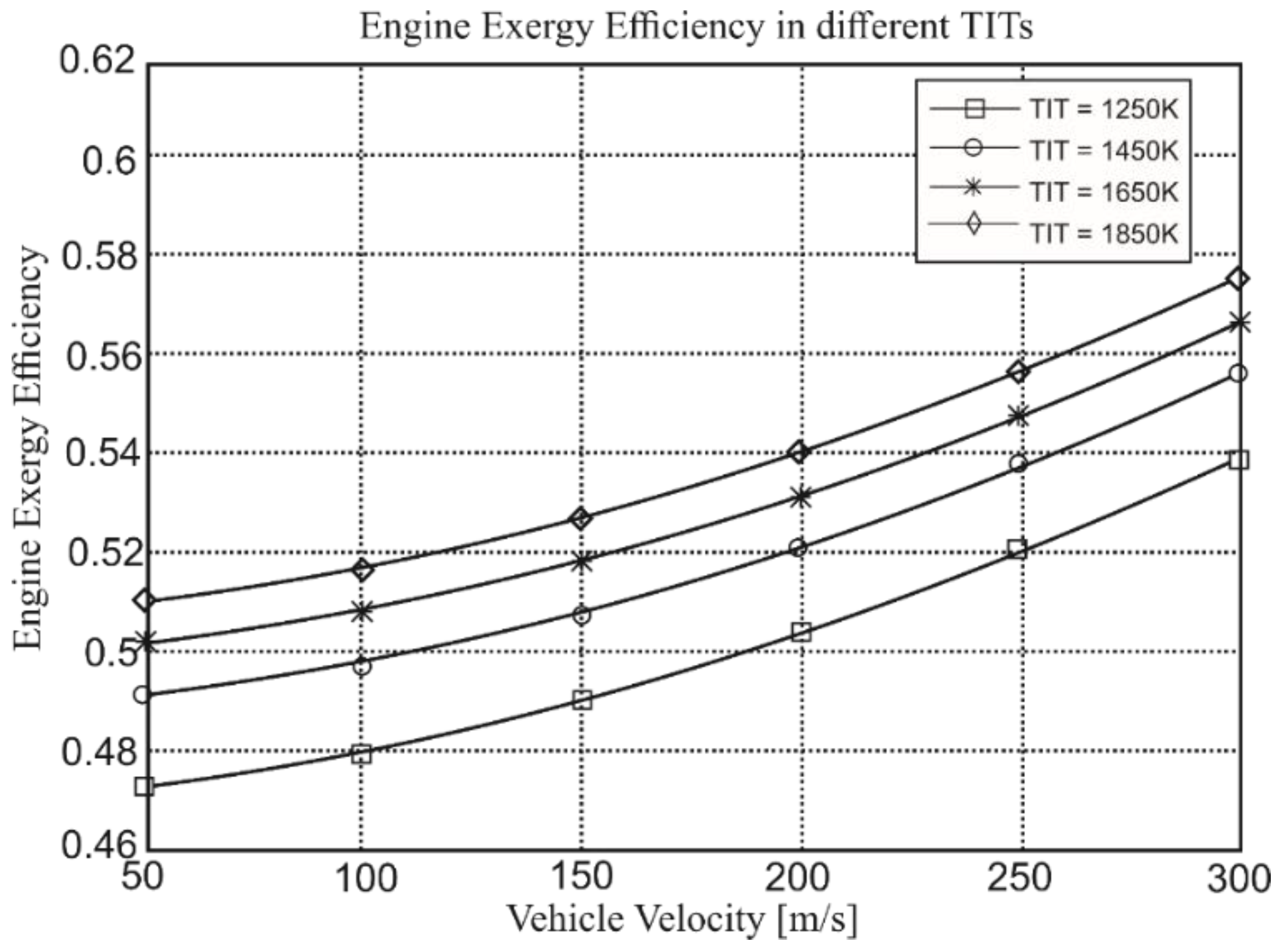

Figure 12 depicts the changes in the exergy efficiency of the engine concerning variations in the temperature entering the turbine and its flight speed. It is observed that as the temperature of the gases entering the turbine and the flight speed of the aircraft increase, the exergy efficiency of the engine is expected to rise. The optimal condition depicted in this diagram is flight at a combustion temperature of 1550 Kelvin and a flight speed of 100 meters per second.

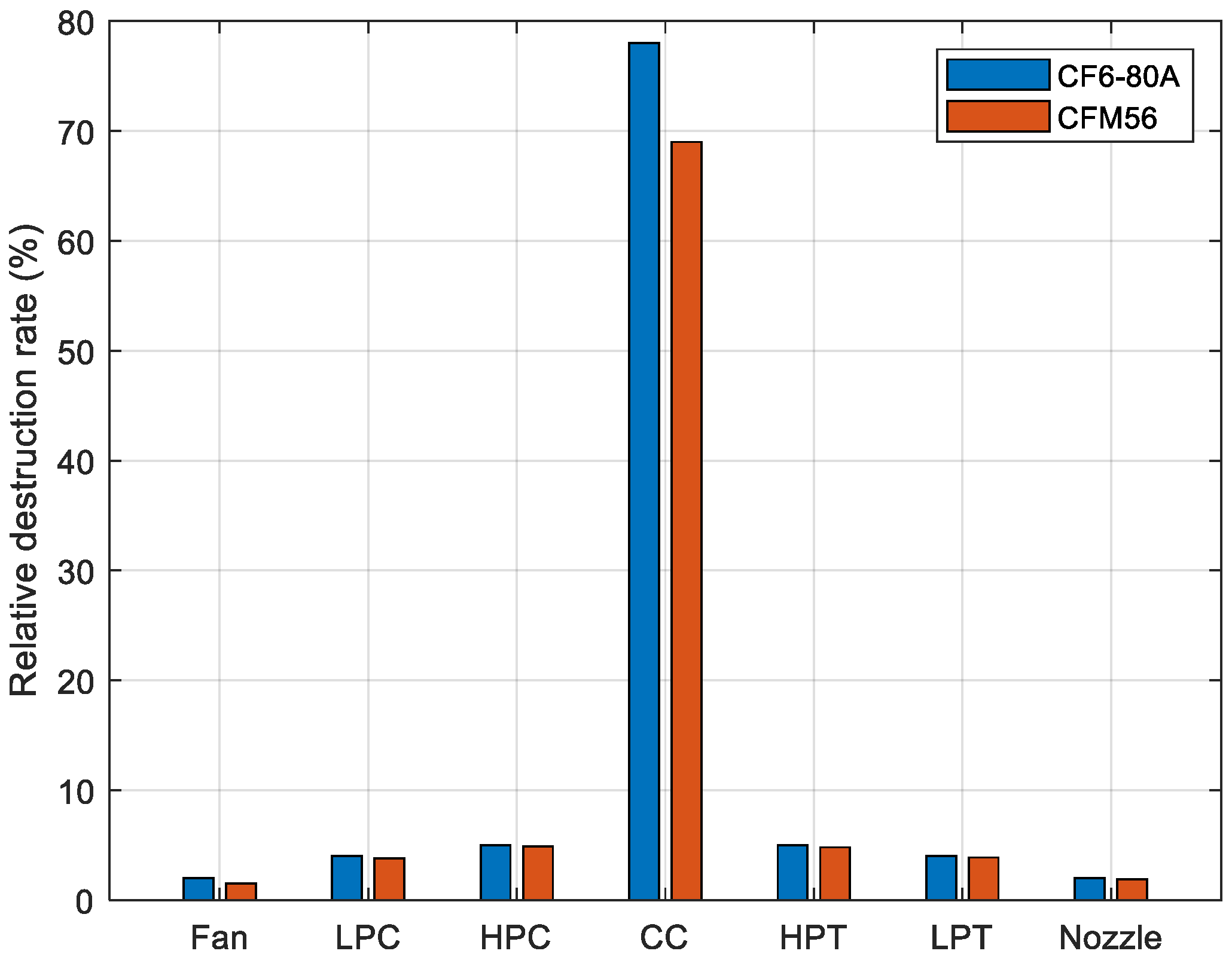

Figure 13 illustrates the relative destruction of exergy in each component of the engine. This diagram holds significant importance as it allows for the measurement of engine performance. By enhancing the relative destruction rate, a high-performance engine can be achieved, leading to reduced gas emissions, lower fuel consumption, and increased profitability. Once again, it is evident that the combustion chamber contributes the most to the destruction of exergy in the engine compared to other components. This is primarily due to irreversibility, as the nature of combustion inherently leads to irreversibility, resulting in a decrease in exergy. The relative destruction rates for the CF6-80A engine components are as follows: fan 2.12%, low-pressure compressor 3.90%, high-pressure compressor 5.21%, combustor 77.21%, high-pressure turbine 5.32%, low-pressure turbine 4.87%, and nozzle 2.11%. For the CFM56 engine, the corresponding relative destruction rates are: fan 2.01%, low-pressure compressor 3.88%, high-pressure compressor 4.98%, combustor 68.01%, high-pressure turbine 4.88%, low-pressure turbine 5.12%, and nozzle 1.98%.

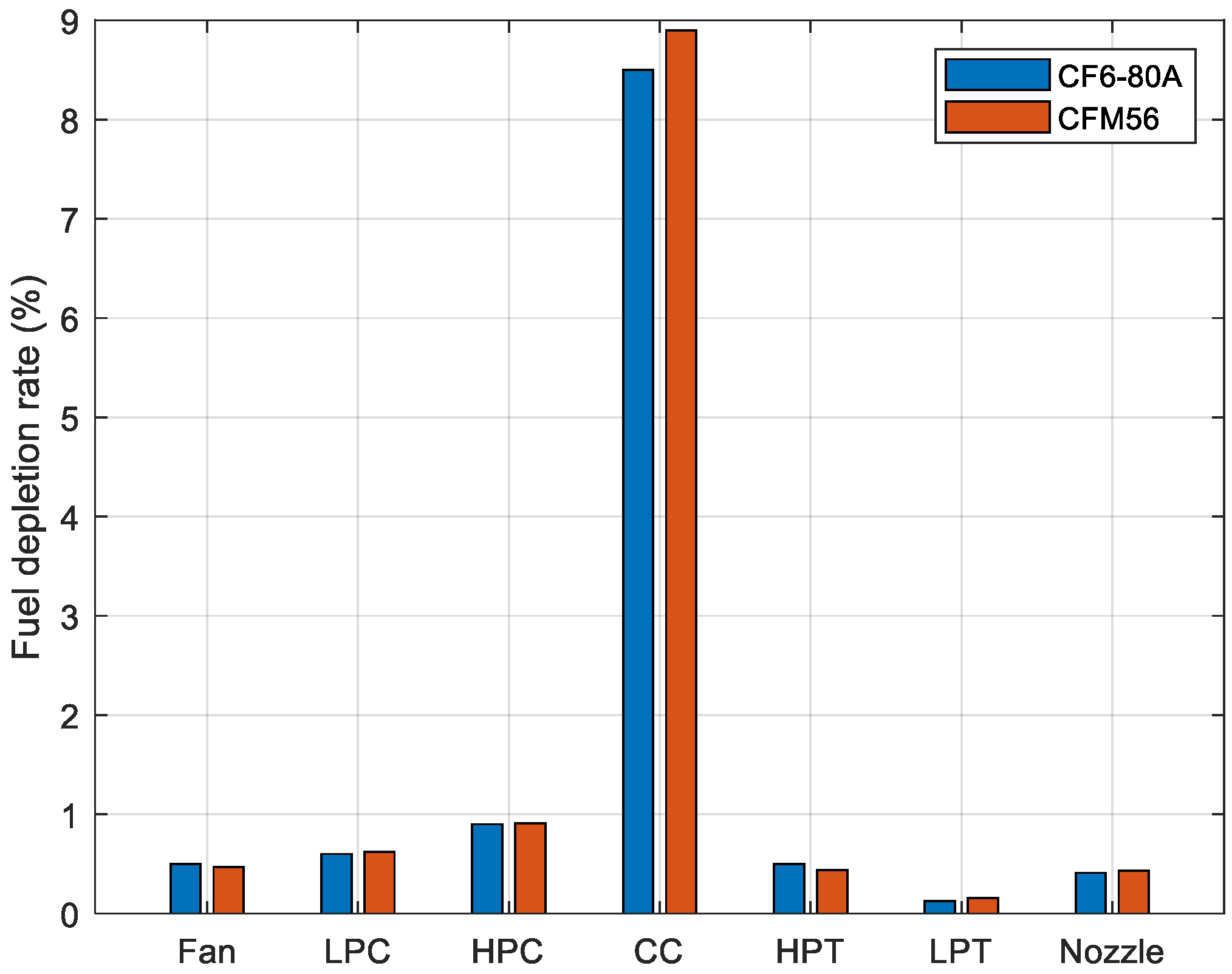

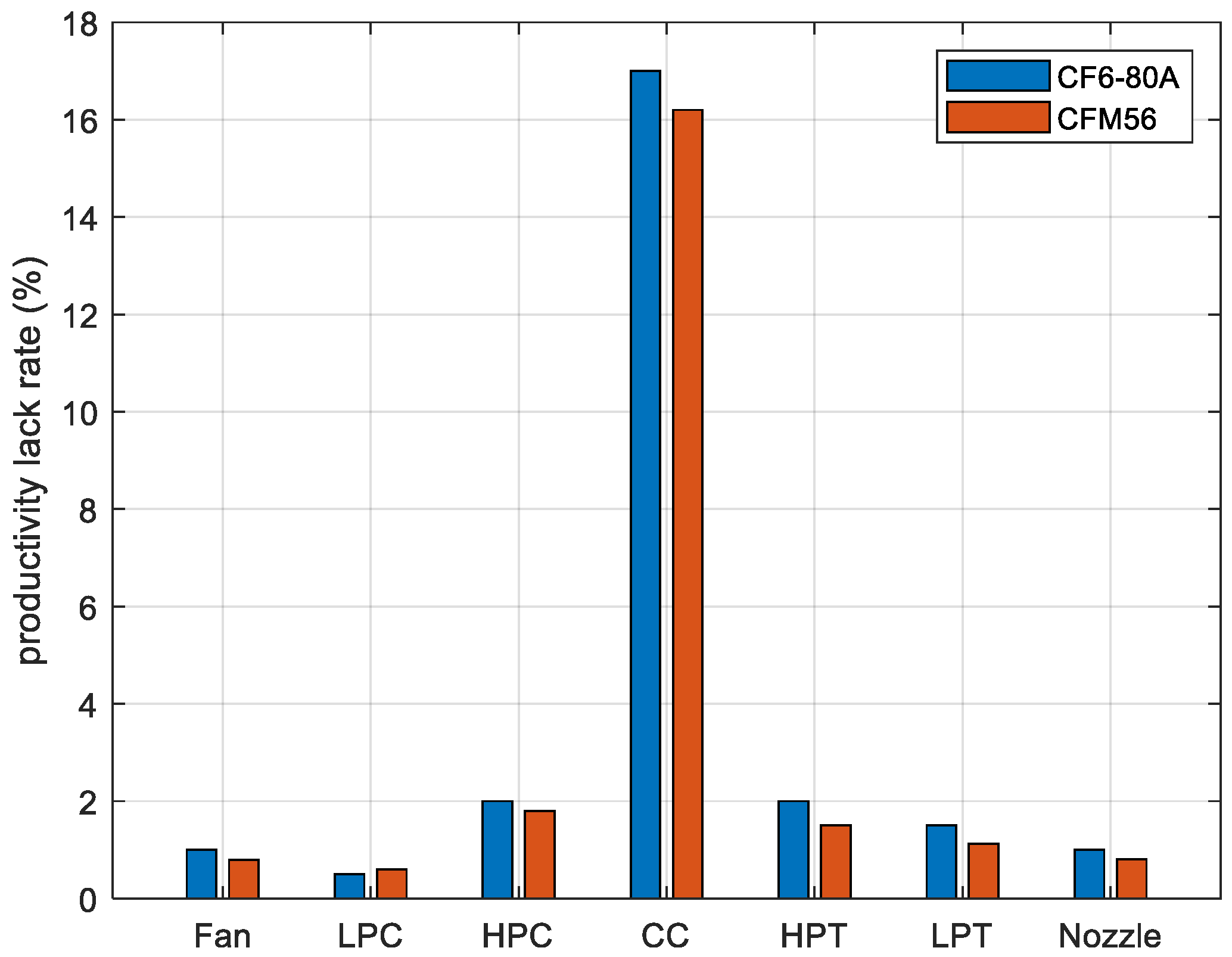

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 illustrate the amount of fuel reduction and the lack of efficiency in the engine, respectively. Once again, the combustion chamber emerges as the component with the highest fuel reduction and lack of efficiency. The fuel reduction rates for the CF6-80A engine components are as follows: low-pressure compressor 0.53%, high-pressure compressor 0.61%, combustor 0.91%, high-pressure turbine 8.51%, low-pressure turbine 0.491%, and nozzle 0.12%. For the CFM56 engine, the corresponding fuel reduction rates are: low-pressure compressor 0.529%, high-pressure compressor 0.63%, combustor 0.92%, high-pressure turbine 8.95%, low-pressure turbine 0.421%, and nozzle 0.13%.

Regarding the productivity lack rate, the CF6-80A engine exhibits rates of 1.01% for the fan, 0.74% for the low-pressure compressor, 2% for the high-pressure compressor, 16.91% for the combustor, 2% for the high-pressure turbine, 1.98% for the low-pressure turbine, and 1.01% for the nozzle. Conversely, for the CFM56 engine, the productivity lack rates are: 0.87% for the fan, 0.91% for the low-pressure compressor, 1.99% for the high-pressure compressor, 16.11% for the combustor, 1.97% for the high-pressure turbine, 1.71% for the low-pressure turbine, and 0.92% for the nozzle.

Meta-Heuristic Optimizers

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) was initially introduced by Kennedy and Eberhart to model the flocking behavior of birds. In PSO, each potential solution is represented as a particle, possessing its own random velocity and position within the search space. The search space is defined as the collection of all possible solutions for the optimization problem. Each particle adjusts its position and velocity based on the best solution (fitness) encountered in the solution space[

19,

20].

Artificial Bee Colony (ABC)

The Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) algorithm was developed by Karaboga[

21], inspired by the foraging behavior of honey bees, to address multidimensional optimization problems. In the ABC algorithm, a potential solution to any problem is represented by a food source, with honeybees tasked with searching for new food sources. The colony of artificial bees in ABC is divided into three groups:

Employed bees: This group consists of bees associated with food sources near the hive.

Onlooker bees: These bees observe the waggle dance performed by the employed bees to share information about food sources with each other.

Scout bees: Responsible for randomly searching for new food sources.

Once a food source is depleted, the employed bees transition to become scout bees to search for another food source.

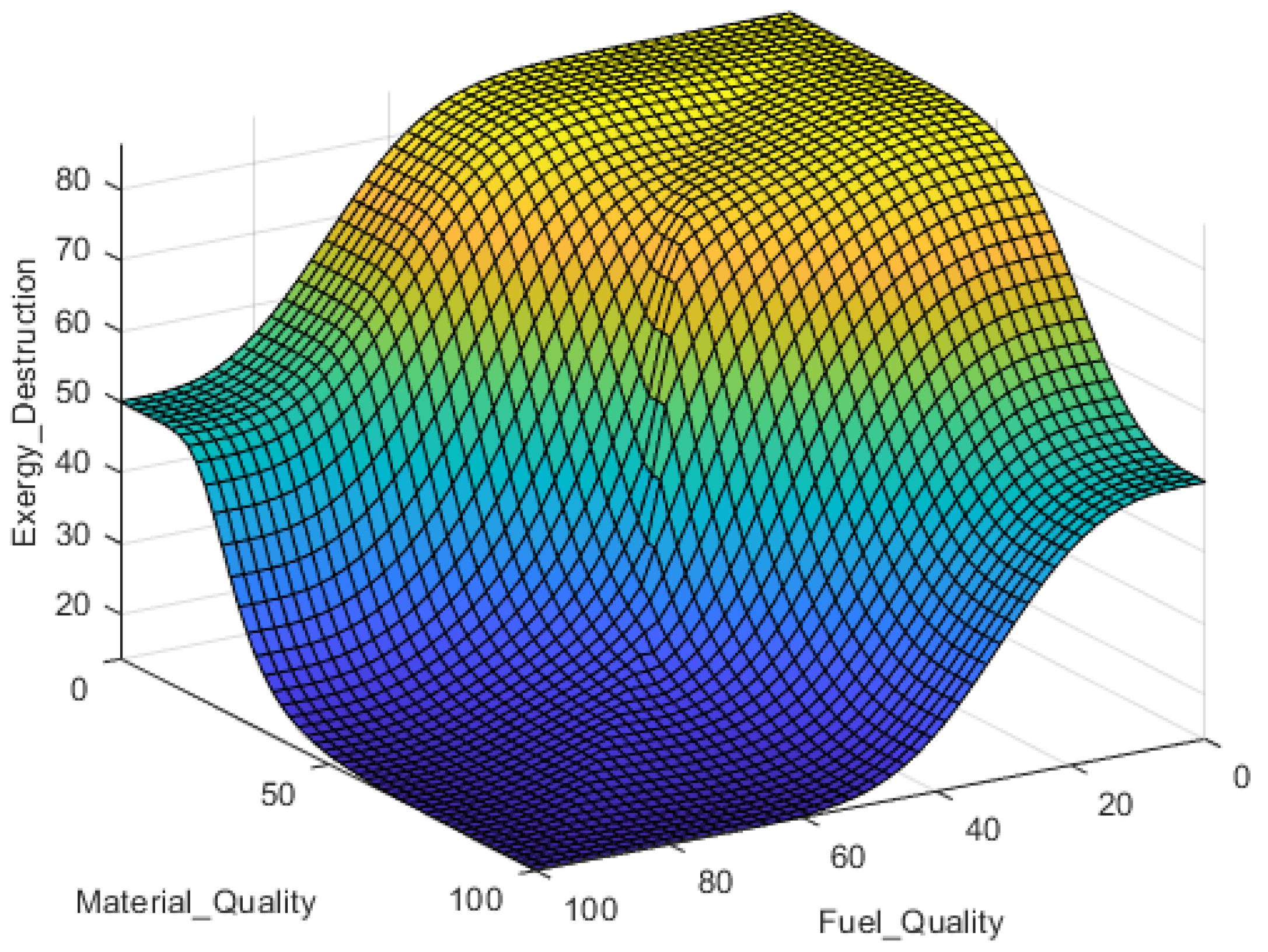

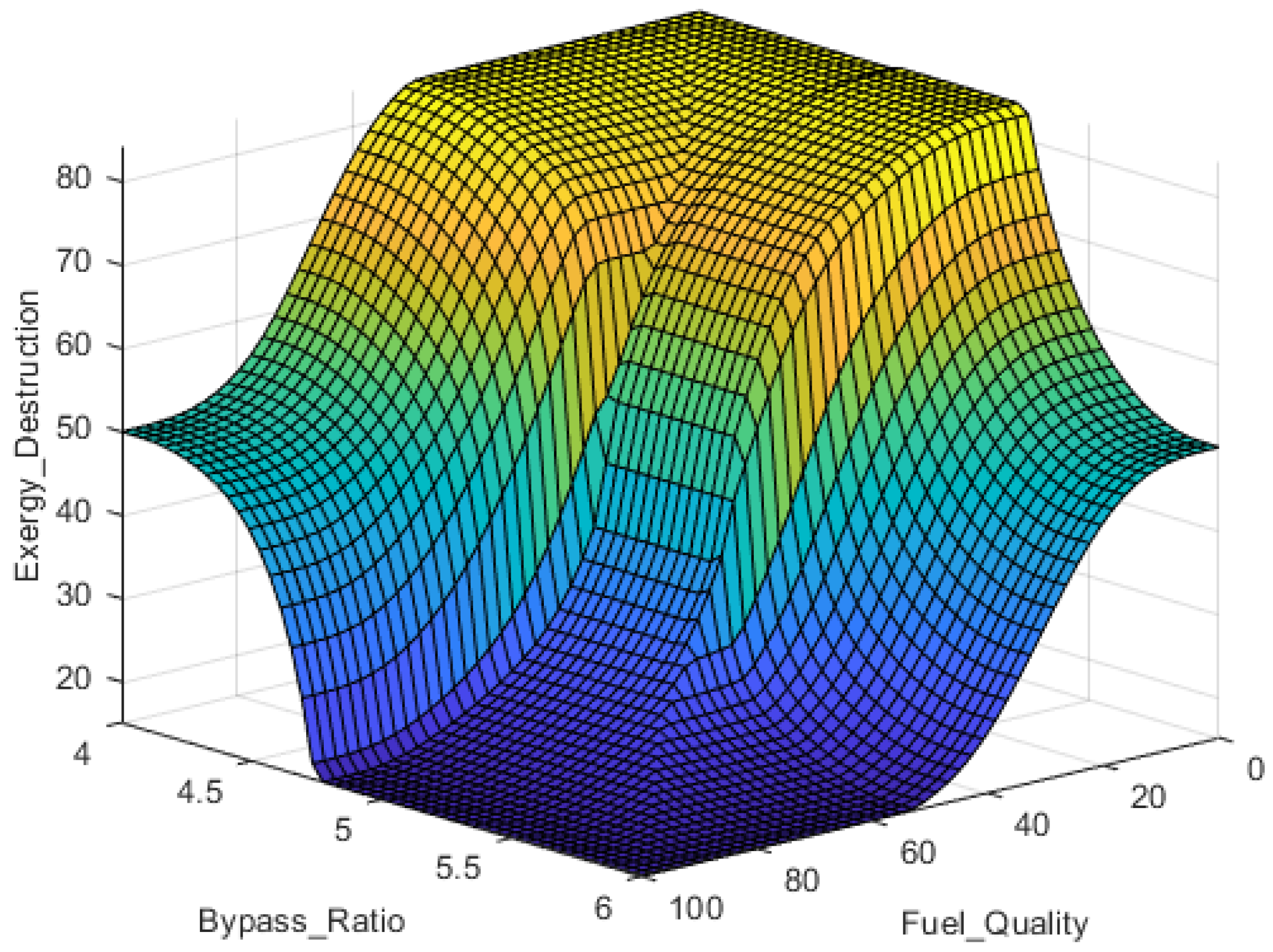

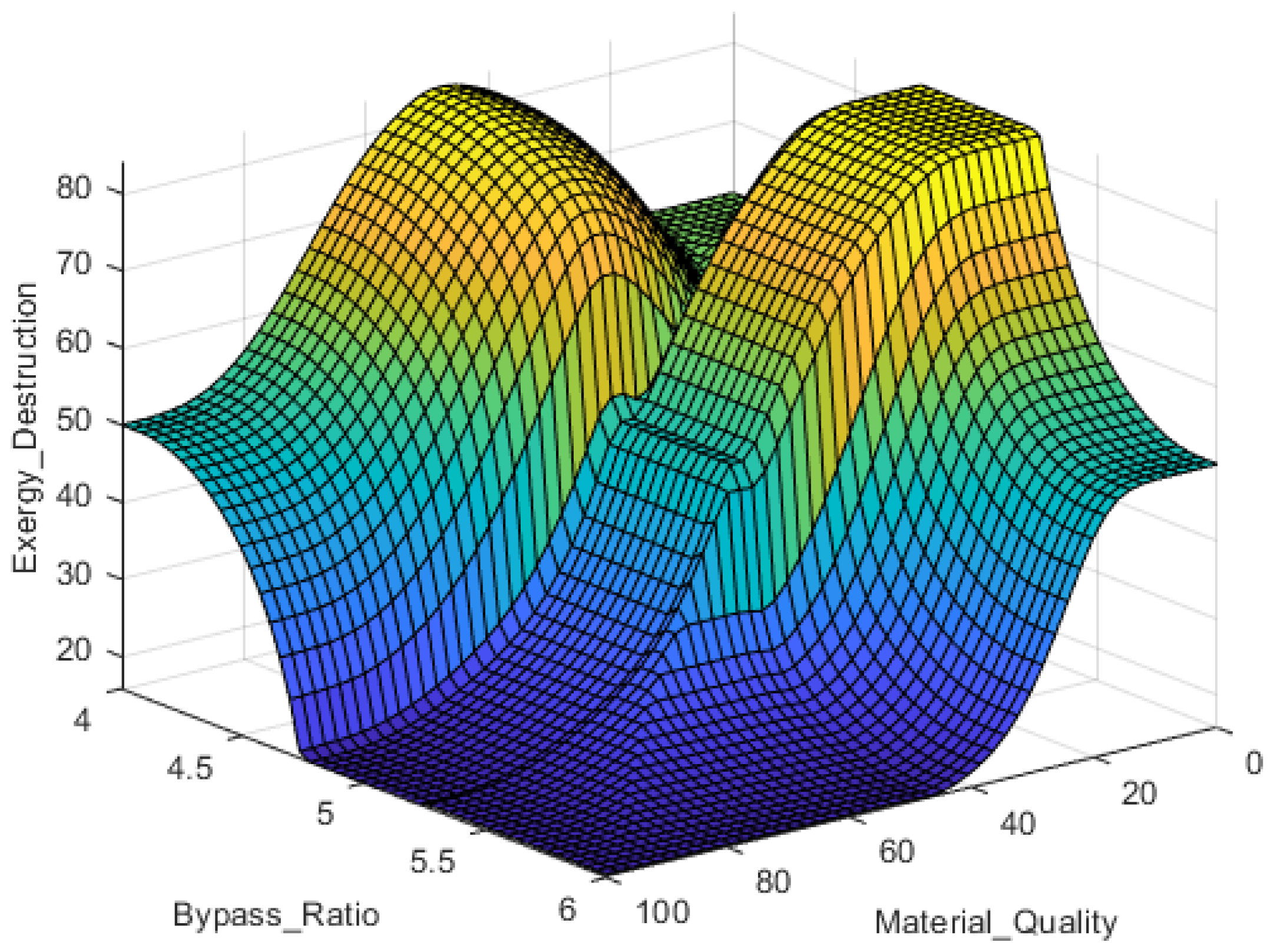

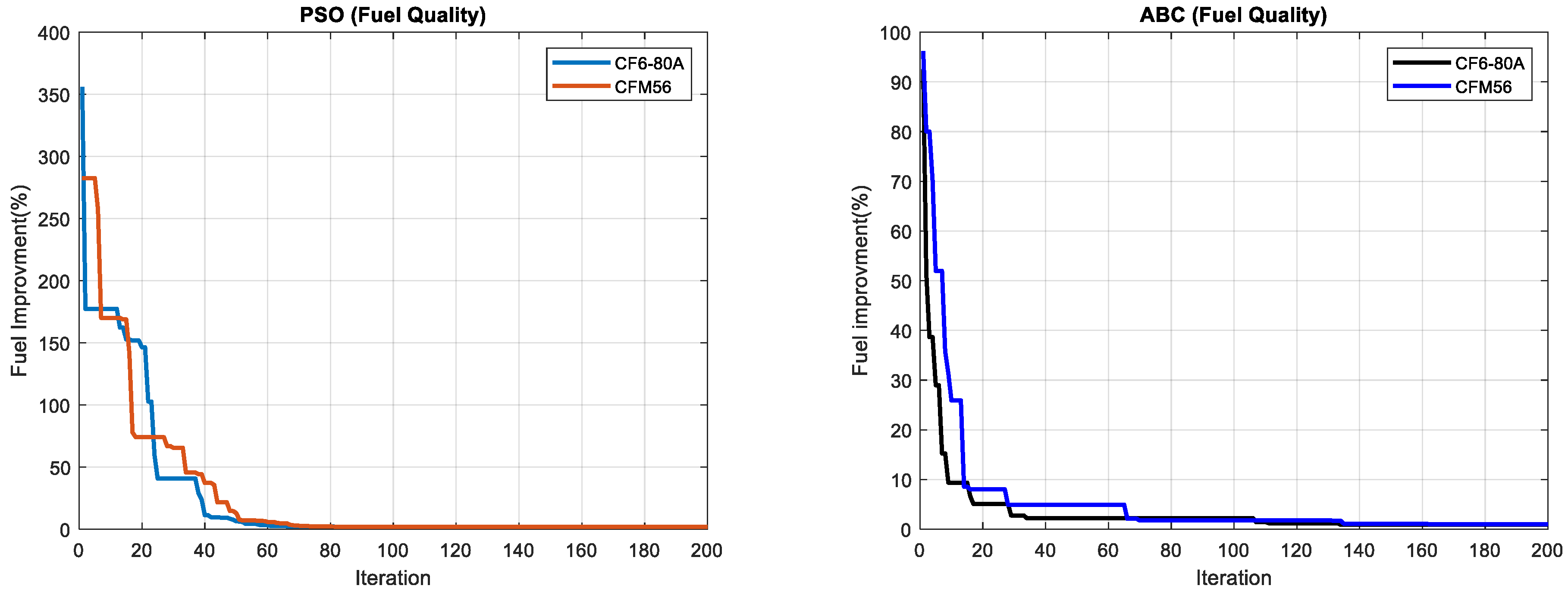

Fuel quality, Material Quality and Bypass Ratio Optimization

In this phase of the study, engine parameter optimization is conducted using meta-heuristic optimization methods. The optimizers employed in this study are Artificial Bee Colony and Particle Swarm Optimization.

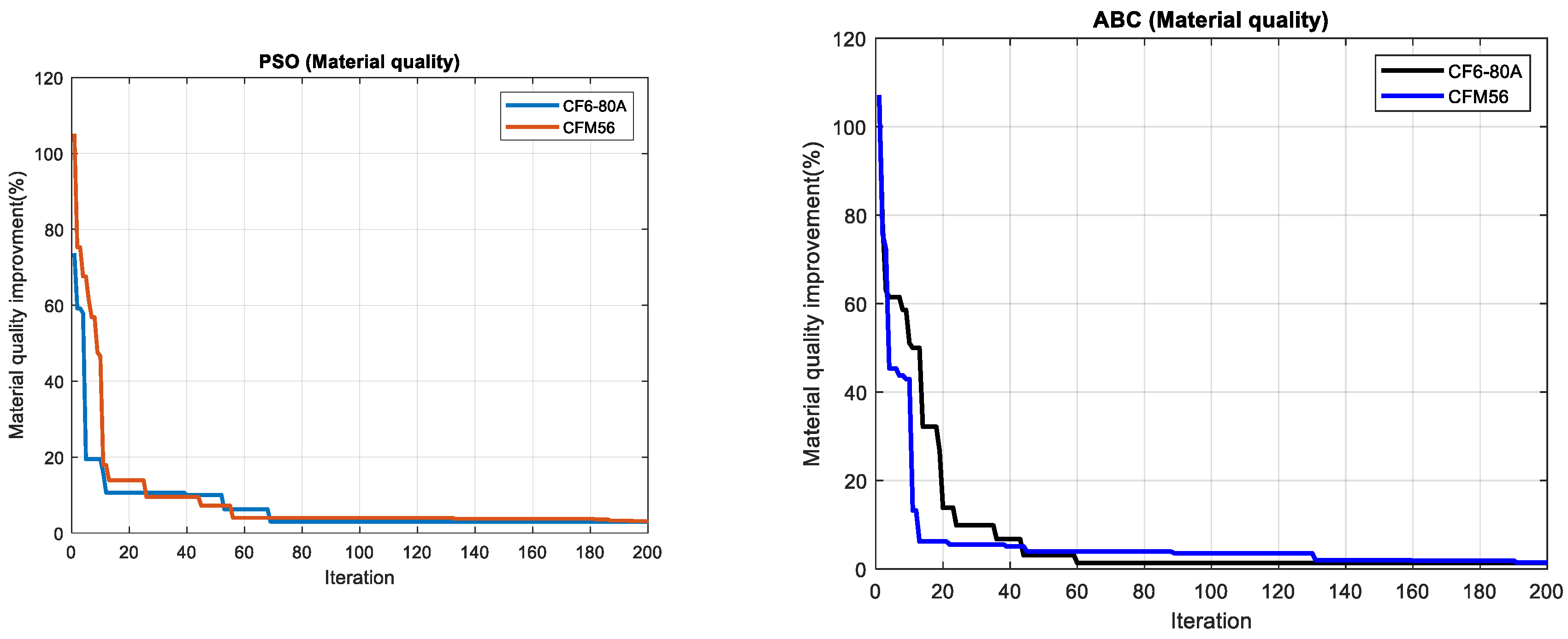

Figure 19 illustrates the optimization of fuel quality achieved by these optimizers. Similarly, the optimization of the bypass ratio is depicted in

Figure 20, and the optimization of material quality is shown in

Figure 21. Subsequently, the results obtained from these optimizers are scrutinized and discussed.

Fuel Quality Optimization

As evident from

Figure 19, the optimizers provided different solutions, indicating varying recommendations regarding the necessary changes in fuel quality to achieve minimum exergy destruction. This discrepancy highlights the influence of optimization algorithms on the final outcomes and underscores the importance of carefully analyzing and interpreting optimization results.

Table 10.

The Results of Each Optimizer.

Table 10.

The Results of Each Optimizer.

| Optimizer |

Result |

| Particle Swarm Optimizer |

0.148 % |

| Artificial Bee Colony Optimizer |

0.2457 % |

According to the results obtained from the optimizers, an increase in fuel quality of 0.148% (with PSO optimizer) or 0.2457% (with ABC optimizer) for the engines will lead to minimum exergy destruction.

Bypass Ratio Optimization

Figure 20.

Optimizers results for bypass ratio of the engines.

Figure 20.

Optimizers results for bypass ratio of the engines.

As depicted in

Figure 20, the optimizers provided differing recommendations regarding the necessary changes in the bypass ratio to achieve minimum exergy destruction. This variability underscores the importance of considering multiple optimization outcomes and conducting further analysis to make informed decisions.

Table 11.

The results of each optimizer.

Table 11.

The results of each optimizer.

| Optimizers |

Result |

| Particle Swarm Optimizer |

0.12% |

| Artificial Bee Colony Optimizer |

0.11% |

According to the results obtained from the optimizers, an increase in the bypass ratio of 0.12% (with PSO optimizer) or 0.11% (with ABC optimizer) for the engines will lead to minimum exergy destruction.

Material Quality Optimization

Figure 21.

Optimizers Results for Material Quality of the Engines.

Figure 21.

Optimizers Results for Material Quality of the Engines.

As evident from

Figure 21, the optimizers provided varying recommendations regarding the required changes in material quality to achieve minimum exergy destruction. This discrepancy highlights the influence of optimization algorithms on the suggested solutions and underscores the importance of carefully analyzing and interpreting optimization outcomes.

Table 12.

The Results of Each Optimizer and Compare.

Table 12.

The Results of Each Optimizer and Compare.

| Optimizers |

Result |

| Particle Swarm Optimizer |

1.01% |

| Artificial Bee Colony Optimizer |

0.5% |

According to the results obtained from the optimizers, increasing the material quality of the engines by 1.01% (with PSO optimizer) or 0.5% (with ABC optimizer) will lead to minimum exergy destruction.