1. Introduction

HIV is still one of the major public health problems worldwide, especially among children and adolescents, with 3.7 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) in 2020 [

1,

2]. Of these PLHIV, 1.8 (1.2-2.3) million were adolescents (AVVIH), and around 88% of them were in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [

3]. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2019 recognised that the reduction of new HIV infections among children, adolescents and young people is slower when compared to adults. For young people aged 20-24, there are about 6000 new infections every day worldwide, [

3] and this age group contains the majority of new HIV infections in SSA. Despite the efforts to limit the spread and effects of the disease, approximately 50% of children worldwide are not on antiretroviral treatment (ART). In Cameroon, the rate of HIV vertical transmission was 15% with suboptimal linkage to ART among people under 25 years of age (44.2%). For adolescents, this rate was respectively 39.7% and 45.1% respectively for 10-14 years and 15-19 years; while for young adults aged 20-24 years, a rate of up to 62% was reported [

4]. For children under 10 years, linkage to ART was even worst (33%) [

4]. In addition, in Cameroon, of the HIV-related deaths recorded in 2020, about 25% occurred among children under 15 years of age [

4]. This is due in part to the high levels of virological failure observed in the paediatric populations.

In the past years, first-line paediatric regimens were based on first generation non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), which have a low genetic barrier to resistance, and second line on protease inhibitors-based regimen (PI/r). Previous studies in Cameroon showed that the virological failure among children and adolescents was about 24% and 47% respectively, with declining performance among those on NNRTIs [

5]. In fact, optimal response to treatment in the paediatric population and among people living with HIV is still a major issue, this is due to the high risk of poor adherence and resistance to antiretrovirals [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Scientific evidence has shown that in Cameroon, around a third of infected children are poorly adherent to treatment, with a difference between urban and rural areas [

12]. Several other factors have been demonstrated to be associated with virological response [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Also, the suboptimal coverage in viral load results in the late detection of treatment failure with accumulation of drug resistance mutations at rates of up to 80% [

12]. This situation might limit the treatment option as children grow up, calling for effective public health strategies for optimal sequencing of treatment regimens to maximise long-term treatment success and reduce AIDS-related deaths.

The armamentarium of HIV drugs has considerably increased in the recent years and the introduction of integrase inhibitors (INIs) into this arsenal has played a key role in viral control. Dolutegravir (DTG), which is a second-generation integrase inhibitor, approved since 2013, is a potent drug with high genetic barrier. Today, DTG-based regimens are recommended by WHO as the preferred regimen for PLWHA starting or switching to an optimal regimen [

16]. Several clinical trials have investigated the safety and efficacy of DTG in adults, adolescents and children living with HIV/AIDS. For example, the ODYSSEY and IMPAACT P1093 clinical trials demonstrated that DTG-based regimens are effective in this population [

9,

17,

18,

19]. These regimens have been investigated in adults and adolescents for first-line and second-line treatment in several clinical trials [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

Currently, Cameroon is transitioning to DTG-based regimen among children and adolescents, but challenges exist in the scaling up of DTG-based regimen, especially among children. In this context, recent studies in Cameroon showed that the virological control is between 74.4% to 88.2% in adolescents [

25,

26] and 64.8% in children. However, these studies have limited sample size and were geographically limited. Therefore, a study with a representative sample size, covering a much larger area in the country is required. Moreover, data on young adult who also generally represent a fragile population are lacking. Studies have shown that viral suppression and undetectable viremia are low compared to adult age [

27,

28]. Mortality is also high among young adults, especially those who were transitioned from the paediatric care [

29]. These observations might be due to gaps in care and adherence issues among this population [

28,

30]. Therefore, the objective of this study is to evaluate virological response and associated factors among children, adolescents, and young adults in the DTG-era, using a large, multicentre, and nationally representative sample.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Inclusion Criteria

Following a nationally representative design, a retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted using the national database on viral load (VL) performed between 2022 and 2023 among children (<10 years), adolescents (10-19 years) and young-adults (20-24 years) within the framework of the Cameroon ART programme. The required information was collected from the database from December 2022 to March 2023. This was a multicentre study performed on a large scale with an exhaustive sampling of all eligible samples at country-level. The inclusion criteria were as follow: (1) age less than 25 years; (2) available information on sex and ART regimens; and (3) available results for HIV-RNA load measurement.

2.2. Study Population and Data Collection

The study population was stratified into five groups: (1) children < 5years; (2) children 5-9 years; (3) adolescents 10-14 years; (4) adolescents 15-19 years; and (5) young adults 20-24 years. Data were collected from all the ten regions of Cameroon through nine HIV reference laboratories, which receive samples from all the follow up units for HIV VL testing in the country. Following the inclusion criteria, the socio-demographic, treatment, and viral load data were collected in an anonymized form to ensure patient confidentiality. Given that the data were not initially collected for research purposes, the database was carefully screened and all the patients with missing or conflicting information were eliminated at the level of data collectors at the sites. All the data were then centralized at the National AIDS Control Committee; to ensure the quality of data, an additional screening was performed.

2.3. Viral Load Measurement

The viral load was measured with a RealTime PCR technique. Currently, in Cameroon, VL is performed using either point-of-care technologies or conventional platforms. The samples are collected, centrifuged and aliquoted at various collection sites, and then transported to the reference laboratory for analysis. Testing is performed using a plasma sample. The detection limit is <40 copies/mL for the laboratories using the Abbott platform (m2000 system), and <390 copies/mL for those using open platforms (Biocentric).

3. Statistical Analysis

After data cleaning process in Microsoft Excel 2019, the file was imported into SPSS version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were summarized as proportions using tables and figures. The proportions among the various categories of the variables of interest were compared using the Chi-square test, Chi-square for trend or Fisher’s Exact test as appropriate. Binary logistic regression model was used to identify factors independently associated with VS. The independent variables that were considered in the model were: sex. age groups, ART duration, ART treatment line, and specific ART regimens. Only the variables with significant p-values in the univariate analysis were fitted and adjusted for in the final multivariate analysis. The statistical significance was set at p<0.05 for all the analyses.

Given the lack of a system to track all the follow-up viral load measurements, in these analyses, we considered only the last available viral load measurement. VS was defined as an HIV-RNA measurement of <1000 copies/mL (according to the WHO guidelines), after at least six months of treatment-start. Because several platforms with varying detection threshold (including point-of-care technologies) were used, we have arbitrary defined low-level viremia in this study as a VL between 400-999 copies/mL. Concerning high-level viremia, it was defined as having a VL measurement of ≥100 000 copies/mL.

4. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and national regulations. This study received all the required administrative authorisations as per the national regulations. This study presents the results for the baseline assessment of Collaborative Initiative for Paediatric HIV Education and Research (CIPHER)-ADOLA study, which aims to accelerate an evidence-informed, human rights-based and integrated HIV response for infants, children, adolescents, and young people living with and affected by HIV. This study received an ethical clearance (CE No 0056 CRERSHC/2023) from the ethics committee of the regional delegation of public health for the Centre region. Anonymity was ensured through the entire study process and investigators had no access to information that could identify individual participants during or after data collection.

5. Results

5.1. Population and Treatment Characteristics

Overall, 7558 individuals (children [11.8%]), adolescents [31.7%], young adults [56.5%]) were analysed. Of note, up to 326 (about 5%) of the patients had less than 5 years. Most of the patients were mainly females (73.2%). The proportion of females significantly increased with increasing age, with up to 82.2% in the age group 20-24 years (

Table 1).

Regarding ART-regimen, all the participants were treatment experienced, with about 44% being on ART for more than 3 years. According to ART regimen line, 89.9%, 10.0%, 0.1% were on 1st line, second line and third line respectively. About 67% of patients on second line have <10 years (

Table 1). Regarding the specific regimens at the time of testing, the most frequent was TDF/3TC/DTG (70.8%), followed by TDF/3TC/EFV or -NVP (12.9%). Some patients were in second line treatment with protease inhibitors-based regimen; notably ABC/3TC/ATV/r or -LPV/r (7.0%). A proportion of about 88% of children <10 years on ABC/3TC/ATV/r or LPV/r.

Regarding the NRTI backbone, as expected, most of the patients received TDF/3TC (86.1%), followed by ABC/3TC (12.7%). Finally, concerning the anchor drug, about 17% of children and about 80% of adolescents received DTG; while for young-adults 20-24 years, 82.9% received DTG. Those receiving DTG-based regimen significantly increased with an increasing age; while LPV/r- or ATV/r-based regimens significantly decreased with increasing age (

Table 1).

5.2. Viral Suppression Among Children, Adolescents and Young Adults According to Sex and Age

The overall VS (defined as a viral load measurement <1000 copies/mL) was 82.3% (95% CI: 81.5-83.2). According to sex, a significantly higher VS was observed in females (83.8% [82.8-84.9]), when compared to males (78.2% [76.4-80.0]), p<0.001.

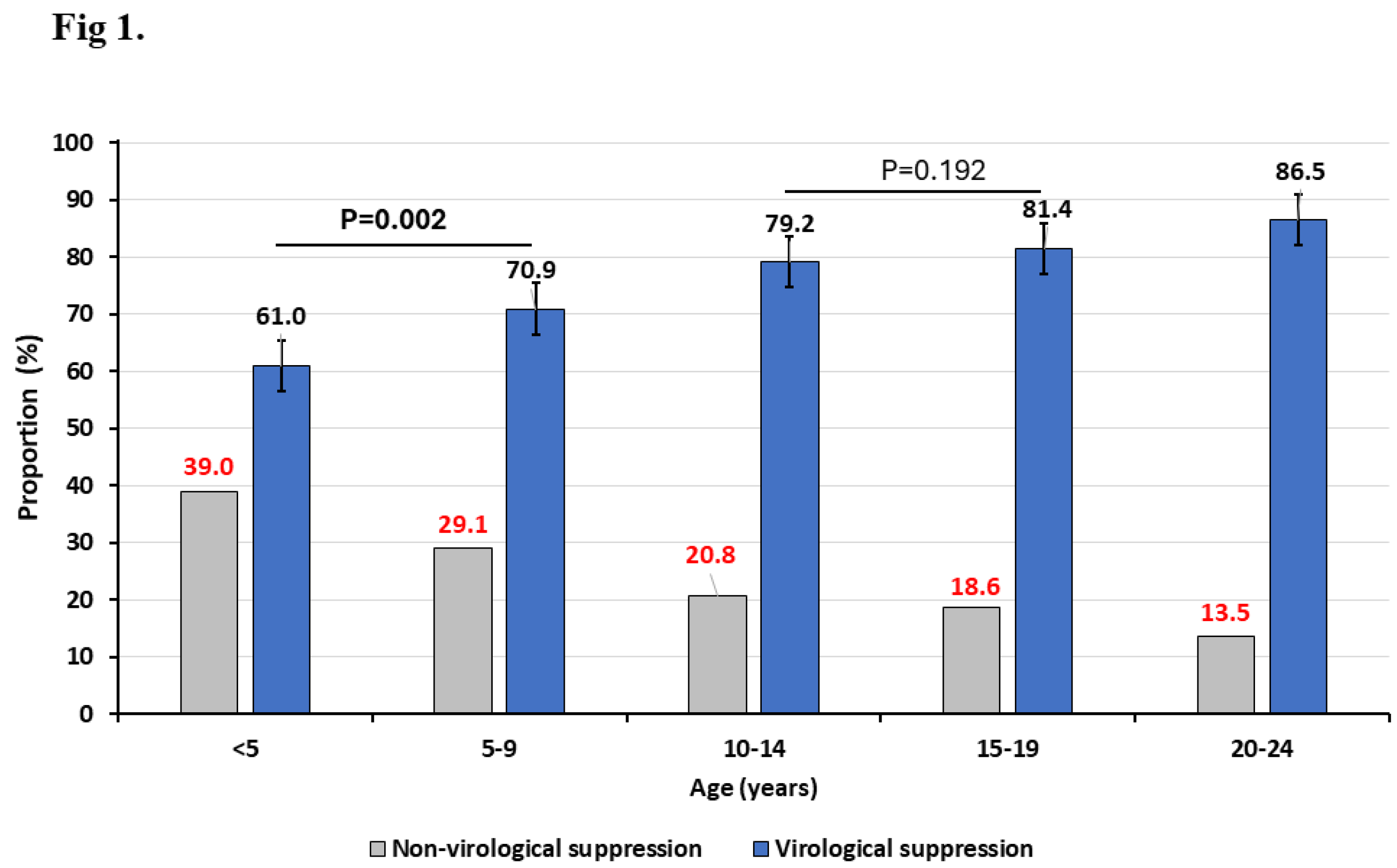

According to ages groups, we have found that the VS (95% CI) among children (<10 years), adolescents (10-19 years) and young adults (20-24 years) was 67.4% (64.3-70.5), 80.7% (79.0-82.2) and 86.2% (85.2-87.2), respectively, p<0.001 (

Figure 1). When further stratifying the age group <10 years into <5 years and 5-9 years, we found that those <5 years showed a significantly lower VS (61.0% [95% CI: 55.7-66.2], when compared to 5-9 years (70.9% [95% CI: 67.1-74.6]), p=0.002. However, when stratifying the adolescent group, a similar VS was observed between those aged 10-14 (79.2% [76.6-81.6]) and those aged 15-19 years (81.4% [79.3-83.3]), p=0.192.

Figure 1 shows that the rate of non-virological suppression significantly decrease with increasing age of the patients.

5.3. Viral Suppression According to Treatment Parameters

Our analysis showed that, at about 6 months after treatment initiation, VS was 81.7% in this population. At 12 and 24 months, VS rate remained stable around 85%, but significantly dropped to about 80% at 36 months after ART initiation. According to ART line, VS was significantly higher in 1st line (84.2%), compared to second line (66.2%) and third line (45.5%) regimens, p<0.001.

The VS according to ART regimen is presented in

Table 2. The regimen with the highest VS level was TDF/3TC/DTG (85.5% [84.5-86.4]), followed by TDF/3TC/EFV (82.8% [80.3-85.1]). PI-based regimen such as ABC/3TC/ATV/r or LPV/r had a high non suppression rate of 36.0%. Children that were treated with ABC/3TC/EFV had a non-suppression rate of up to 33.2%.

When considering the NRTI backbone, TDF/3TC had the highest VS rate (84.8% [83.9-85.6]), compared to ABC/3TC (67.2% [64.2-70.1]) and AZT/3TC (67.4 [57.2-76-5]), p<0.001. Finally, according to anchor drug, DTG showed the highest VS rate (85.1 [84.1-86]), followed by EFV or NVP (80.0% [77.6-82.1]). ATV or LPV showed the highest non suppression rate (34.4%).

5.4. Levels of Viral Loads Among Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults

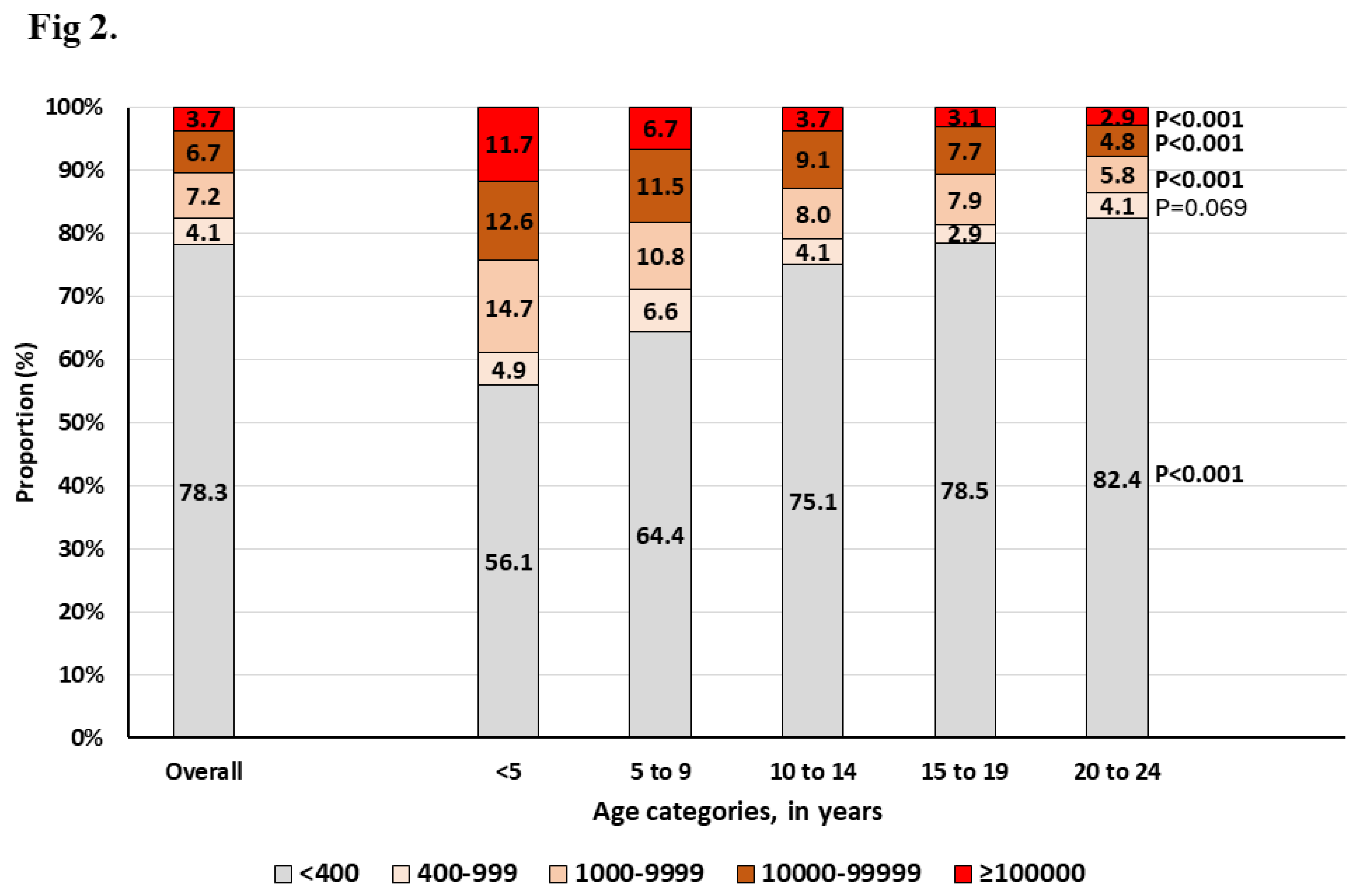

According to viral load levels and age,

Figure 2 shows an increasing proportion of those with VL<400 copies/mL (including those that are undetectable) with increasing age; the lowest being observed in those <5 years (56.1%) and the highest in those aged 20-24 years (82.4%), p<0.001. When looking at the proportion of those with low-level viremia (LLV, defined here as HIV-RNA between 400-999 copies/mL), children, adolescents and young adults showed a proportion of 5.9%, 3.5% and 4.1%, respectively, p<0.001.

Looking at LLV according to anchor drug, we found that it was highest among those receiving PI-based regimen (5.5%), followed by NNRTI-based regimen (4.8%); DTG-based regimen being the lowest (3.7%), p=0.030. Interestingly, the overall proportion of those failing (HIV-RNA >1000 copies/mL) with very high-level viremia (HLV, >100 000 HIV-RNA copies/mL) was 21.1%. Of these, 20.4%, 16.9%, 27.5% was observed among those receiving DTG, EFV or NVP, and ATV or LPV, p= 0.010. Furthermore, our analysis evidenced that the proportion of patients with very HLV at failure was significantly higher among those <5 years (11.7%), and this proportion significantly decreased with increasing age (

Figure 2).

5.5. Factors Associated with Viral Suppression Among Children, Adolescents and Young Adults

The regression model was built using all the variables in

Table 1. At the univariate level, we found that sex, age, ART duration, ART line and ART regimens were confounders After adjusting for all these variables, only age, ART duration and ART regimen were found to be independently associated with viral suppression. In particular, for age, when compared to those 20-24 years, age groups <5 years (aOR [95% CI]: 0.469 [0.331-0.665]), 5-9 years (aOR [95% CI]: 0.702 [0.511-0.965]), 10-14 years (aOR [95% CI]: 0.685 [0.564-0.833]) and 15-19 years (aOR [95% CI]: 0.722 [0.612-0.851]) were all negatively associated with VS. Regarding ART duration, compared to those on ART for >36 months, those on ART for 24 months showed a higher odds of VS (aOR [95% CI]: 1.271 [1.037-1.557]). Concerning ART regimen, compared to TDF/3TC/DTG, apart from TDF/3TC/EFV, all the other regimen showed a significantly lower odd of VS. In particular, TDF/3TC/DTG had about 2.3 and 1.5 odds of VS when compared to ABC/3TC/ATT/r or LPV/r and ABC/3TC/DTG, respectively.

6. Discussion

According to the new global alliance, a key pillar for ending AIDS in children by 2030 is the access of children and adolescents to optimized treatment. Limited evidence from SSA calls for large-scale investigation on viral suppression in children, adolescents and young adults in Cameroon considering sociodemographic and therapeutic features. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that reports VS in a nationally representative sample of children and adolescents (more than 3200 patients), collected over the Cameroon’s national territory. It should be noted that Cameroon is currently in the transition phase to DTG-based regimens, also among children and adolescents. The result of our study shows that the viral suppression among children, adolescents and young adults in Cameroon is suboptimal (about 82%), which is below the global UNAIDS target of 95% by 2025. A recent study in Cameroon by Fokam et al. [

25] showed that the overall (including adults) viral suppression was 89.8%; which is higher compared to the rate observed in our study. The prevalence observed among young adults in our population is close to the VS rate observed in this study. This may be partly explained by the fact that, even though some young adults still struggle with problems such ART adherence and stigma, most of them have already transitioned to optimal ART regimen, notably, TDF/3TC/DTG (TLD). The proportion of young adults on TLD in our study was more than 80% (Table.1).

On the other hand, VS rate was much lower among children and adolescents, where the VS rates were respectively about 67% and 81%. In fact, we have seen that, children <5 years recorded the worst VS rate, with only 61%. The study by Fokam et al. reported a lower but similar VS among children [

25]. The management of ART treatment in the paediatric populations is complex, with sometimes complex formulations. This might partly justify the poor virological control among children. Compared to adult populations, children are usually receiving suboptimal regimen. In this study, the proportion of children <5 years and 5-19 years on protease inhibitors-based regimen (second line) was 68% and 44%, respectively. In many developing settings, there is a lack of optimal paediatric formulations and adequate training of health care workers in the follow up of HIV infected children. The creation of paediatric centres of excellence for HIV in Cameroon and other developing countries will hopefully reduce this gap. The transition from current regimen to more potent regimen based on paediatric DTG is slow but ongoing in Cameroon. The findings showing that DTG-based regimen was a positive predictor of VS is a call to rapidly scale up DTG-based regimen in Cameroon and similar settings.

Concerning adolescents, compared to the data of previous years which showed a VS of about 53%, [

31] the VS has significantly increased and this study indicate a performance of about 81%. Despite this progress, the improvement of viral control among children and adolescents is much slower compared to adults. A large scale study among children and adolescents showed that the viral suppression was 36% at 1 year, 30% at 2 years, and 24% at 3 years after ART initiation [

32]. This low performance could be explained by the fact that data were collected in the non-DTG era. The VS among adolescents in this study is also slightly different from the data reported in recent studies by Fokam et al. (74%) [

25] and Djiyou et al. (89%). [

26] This difference might be attributed to the difference in sample size and national representativeness of the study sample size. The improvement in VS among adolescents can be attributed to many factors, among which the transition to DTG-based regimen, the psychological support and creation of social support groups that have had a huge impact on ART adherence. In their study assessing the impact of adherence on viral suppression, Tanyi et al. showed that viral suppression was better when adherence to treatment was good [

24]. A study conducted in Cameroon also demonstrated that virologic response appears to be better in adolescents who followed therapeutic education sessions [

33]. Therefore, achieving the 95% VS target by 2025 in this group will require continuous efforts in the scale up of DTG-based regimens and providing appropriate social and psychological support strategies. The approval of long acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine among eligible adolescents represent an additional opportunity to improve VS. It is therefore important to provide some evidence on the possible introduction of long acting in this fragile population which struggles with some issues related to adolescence. In this regard, the CIPHER-ADOLA study which aims at optimizing the follow up of HIV infected adolescents will fill some gaps. Enough literature exists on the potency of DTG-based regimen [

18], even among those who were previously exposed to boosted protease inhibitors. Even though drug resistance test was not performed in this study, previous reports indicated that there is a low ART switch rate from one line to the other. Previous studies reported an alarming levels of drug resistance among the adolescent populations in Cameroon [

34]. This means that, access to viral load testing should be improved to confirm virological failure and proceed with switch to another therapeutic lines. Efforts should be also made to improve the access to resistance testing, especially in the paediatric populations.

Regarding the factors associated with VS among children, adolescents, and young adults in Cameroon, we have found that age, ART regimen and ART duration were independently associated with VS. This observation has been observed in studies conducted in a similar setting [

25,

26,

35]. However, concerning sex, unlike in other studies, it was not found to be a predictor of VS in our study population.

Beyond VS, our results evidenced that in our setting, a high proportion (>20%) of virologically non-suppressed patients failed their ART with very high-level viremia. Besides, in this population, we have seen that the proportion of those who are virologically suppressed (<1000 HIV-RNA copies/mL) but showed a low-level viremia is not negligeable. LLV is now a rising problem, and appropriate measures should be taken to reduce the extend of this phenomenon. Of note, those who failed their ART with LLV were less common in those receiving a DTG-based regimen. However, for high-level viremia, we did not see any difference in terms of anchor drug. More studies are warranted to better understand the HIV viral dynamics among the paediatric populations.

This study has some limitations that should be overcome in subsequent analysis. First, the data analysed here were not collected for research purpose, therefore there is a possibility that biases were introduced. Secondly, resistance test results and adherence data that could have help to better characterize the reasons for non-viral suppression were not available. However, appropriate statistical methods were implemented to make corrections, whenever necessary. The major strength of this study is that analyses were performed on a large sample size collected from all the ten regions of Cameroon, thus, nationally representative.

7. Conclusions

In this Cameroonian paediatric population with varying levels of transition to DTG (20% in children and 80% in adolescents), overall VS (82.3%) remains below the 95% UNAIDS targets, especially among children <10 years (67.4%). Interestingly, predictors of non-VS are younger age and non-DTG based regimens. Thus, efforts toward eliminating paediatric AIDS should prioritise a rapid transition to DTG-based regimen, especially for younger children who remain largely underserved in this new ART-era.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Joseph FOKAM, Yagai Bouba, Maria Mercedes Santoro, Francesca Ceccherini-Silberstein, Vittorio Colizzi, Alexis Ndjolo and Carlo Federico Perno; Data curation, Yagai Bouba, Rogers Ajeh, Rose Armelle Ada, Sabine Atsinkou, Roger Martin Onana, Alex Durand Nka, Aude Ka’e, Nadine Fainguem, Michel Carlos Tchouaket and Comfort Vuchas; Formal analysis, Yagai Bouba, Dominik Guebiapsi, Roger Martin Onana, Alex Durand Nka and Davy-Hyacinthe Gouissi; Funding acquisition, Joseph FOKAM, Yagai Bouba, Maria Mercedes Santoro, Francesca Ceccherini-Silberstein, Vittorio Colizzi, Alexis Ndjolo and Carlo Federico Perno; Investigation, Joseph FOKAM, Yagai Bouba, Dominik Guebiapsi, Suzane Essamba, Ebiama Lifanda, Yakouba Liman, Nancy Barbara Mbengono, Audrey Raissa Djomo, Suzie Tetang, Samuel Martin Sosso, Jocelyne Carmen Babodo, Olivia Francette Ambomo, Edith Michele Temgoua, Caroline Medouane, Sabine Atsinkou, Justin Leonel Mvogo, Roger Martin Onana, Jean de Dieu Anoubissi, Alex Durand Nka, Davy-Hyacinthe Gouissi, Aude Ka’e, Nadine Fainguem, Rachel Kamgaing, Désiré Augustin Takou, Michel Carlos Tchouaket, Ezechiel Semengue, Marie Amougou, Julius Nwobegahay, Comfort Vuchas, Anna Nsimen, Bertrand Eyoum, Sandra Gatchuessi, Francis Ateba and Daniel Kesseng; Methodology, Joseph FOKAM, Yagai Bouba, Rogers Ajeh, Dominik Guebiapsi, Suzane Essamba, Albert Franck Zeh Meka, Ebiama Lifanda, Rose Armelle Ada, Yakouba Liman, Nancy Barbara Mbengono, Audrey Raissa Djomo, Suzie Tetang, Samuel Martin Sosso, Jocelyne Carmen Babodo, Olivia Francette Ambomo, Edith Michele Temgoua, Caroline Medouane, Sabine Atsinkou, Justin Leonel Mvogo, Jean de Dieu Anoubissi, Alice Ketchaji, Alex Durand Nka, Davy-Hyacinthe Gouissi, Aude Ka’e, Nadine Fainguem, Rachel Kamgaing, Désiré Augustin Takou, Michel Carlos Tchouaket, Marie Amougou, Julius Nwobegahay, Comfort Vuchas, Anna Nsimen, Bertrand Eyoum, Sandra Gatchuessi, Francis Ateba, Daniel Kesseng, Serge Clotaire Billong, Daniele Armenia, Maria Mercedes Santoro, Francesca Ceccherini-Silberstein, Hadja Hamsatou, Alexis Ndjolo, Carlo Federico Perno and Anne-Cécile Zoung-Kanyi Bissek; Project administration, Joseph FOKAM, Yagai Bouba, Désiré Augustin Takou, Maria Mercedes Santoro, Francesca Ceccherini-Silberstein and Alexis Ndjolo; Supervision, Joseph FOKAM, Yagai Bouba, Suzane Essamba, Suzie Tetang, Samuel Martin Sosso, Julius Nwobegahay, Francis Ateba, Francesca Ceccherini-Silberstein, Paul Koki, Hadja Hamsatou, Alexis Ndjolo, Carlo Federico Perno and Anne-Cécile Zoung-Kanyi Bissek; Validation, Joseph FOKAM, Yagai Bouba, Albert Franck Zeh Meka, Jocelyne Carmen Babodo, Alice Ketchaji, Rachel Kamgaing, Marie Amougou, Paul Koki, Carlo Federico Perno and Anne-Cécile Zoung-Kanyi Bissek; Visualization, Yagai Bouba, Dominik Guebiapsi and Alex Durand Nka; Writing – original draft, Joseph FOKAM, Yagai Bouba, Dominik Guebiapsi, Yakouba Liman, Alex Durand Nka, Davy-Hyacinthe Gouissi, Aude Ka’e, Michel Carlos Tchouaket and Ezechiel Semengue; Writing – review & editing, Rogers Ajeh, Edith Michele Temgoua, Jean de Dieu Anoubissi, Alice Ketchaji, Serge Clotaire Billong, Daniele Armenia, Maria Mercedes Santoro, Paul Koki, Vittorio Colizzi, Alexis Ndjolo, Carlo Federico Perno and Anne-Cécile Zoung-Kanyi Bissek.

Funding

This research was funded by the International AIDS Society (IAS) through the Collaborative Initiative for Paediatric HIV Education and Research (CIPHER). The APC was covered by the CIPHER grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the regional delegation of public health for the Centre region of Cameroon (CE No 0056 CRERSHC/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was not required for this part of the study because data were obtained from a national database of viral loads. However, ethical clearance was obtained before accessing the data and anonymity was ensured through the entire study process, investigators had no access to information that could identify participants during or after data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the health care workers in the HIV Follow up units and in the references HIV laboratories that contributed to the collection of data related to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization HIV/AIDS Fact Sheet 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- UNAIDS Global HIV & AIDS Statistics — Fact Sheet 2021. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- UNICEF HIV and AIDS in Adolescents - 2021 Data. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/hiv-aids/ (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- CNLS Rapport Annuel Des Activites de Lutte Contre Le VIH/Sida; 2021.

- Fokam, J.; Sosso, S.M.; Yagai, B.; Billong, S.C.; Djubgang Mbadie, R.E.; Kamgaing Simo, R.; Edimo, S.V.; Nka, A.D.; Tiga Ayissi, A.; Yimga, J.F.; et al. Viral Suppression in Adults, Adolescents and Children Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy in Cameroon: Adolescents at High Risk of Virological Failure in the Era of “Test and Treat. ” AIDS Res. Ther. 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koay, W.L.A.; Kose-Otieno, J.; Rakhmanina, N. HIV Drug Resistance in Children and Adolescents: Always a Challenge? Curr. Epidemiol. Reports 2021, 8, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salou, M.; Dagnra, A.Y.; Butel, C.; Vidal, N.; Serrano, L.; Takassi, E.; Konou, A.A.; Houndenou, S.; Dapam, N.; Singo-Tokofaï, A.; et al. High Rates of Virological Failure and Drug Resistance in Perinatally HIV-1-Infected Children and Adolescents Receiving Lifelong Antiretroviral Therapy in Routine Clinics in Togo. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2016, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokam, J.; Sosso, S.M.; Yagai, B.; Billong, S.C.; Djubgang Mbadie, R.E.; Kamgaing Simo, R.; Edimo, S.V.; Nka, A.D.; Tiga Ayissi, A.; Yimga, J.F.; et al. Viral Suppression in Adults, Adolescents and Children Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy in Cameroon: Adolescents at High Risk of Virological Failure in the Era of “Test and Treat. ” AIDS Res. Ther. 2019, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viani, R.M.; Ruel, T.; Alvero, C.; Fenton, T.; Acosta, E.P.; Hazra, R.; Townley, E.; Palumbo, P.; Buchanan, A.M.; Vavro, C.; et al. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Dolutegravir in Treatment-Experienced Adolescents with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection: Results of the Impaact P1093 Study. J. Pediatric Infect. Dis. Soc. 2020, 9, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dow, D.E.; Shayo, A.M.; Cunningham, C.K.; Mmbaga, B.T. HIV-1 Drug Resistance and Virologic Outcomes among Tanzanian Youth Living with HIV. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 38, 617–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, N.; Lowery, A.; Brown, L.K. Adherence to HIV Care and Associated Health Functioning among Youth Living with HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. Aids Rev. 2021, 22, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokam, J.; Takou, D.; Njume, D.; Pabo, W.; Santoro, M.M.; Njom Nlend, A.E.; Beloumou, G.; Sosso, S.; Moudourou, S.; Teto, G.; et al. Alarming Rates of Virological Failure and HIV-1 Drug Resistance amongst Adolescents Living with Perinatal HIV in Both Urban and Rural Settings: Evidence from the EDCTP READY-Study in Cameroon. HIV Med. 2021, 22, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, D.; Di Carlo, D.; Flandre, P.; Bouba, Y.; Borghi, V.; Forbici, F.; Bertoli, A.; Gori, C.; Fabeni, L.; Gennari, W.; et al. HIV MDR Is Still a Relevant Issue despite Its Dramatic Drop over the Years. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumetie, A.; Moges, N.A.; Teshome, M.; Gedif, G. Determinants of Virological Failure Among HIV-Infected Children on First-Line Antiretroviral Therapy in West Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. HIV. AIDS. (Auckl). 2021, 13, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, D.; Bouba, Y.; Gagliardini, R.; Gori, C.; Bertoli, A.; Borghi, V.; Gennari, W.; Micheli, V.; Callegaro, A.P.; Gazzola, L.; et al. Evaluation of Virological Response and Resistance Profile in HIV-1 Infected Patients Starting a First-Line Integrase Inhibitor-Based Regimen in Clinical Settings. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 130, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Testing, Treatment, Service Delivery and Monitoring : Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. 548.

- Viani, R.M.; Alvero, C.; Fenton, T.; Acosta, E.P.; Hazra, R.; Townley, E.; Steimers, D.; Min, S.; Wiznia, A. Safety, Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of Dolutegravir in Treatment-Experienced HIV-1 Infected Adolescents : Forty-Eight-Week Results from IMPAACT P1093. In Proceedings of the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal; 2015; Vol. 34; pp. 1207–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Waalewijn, H.; Chan, M.K.; Bollen, P.D.J.; Mujuru, H.A.; Makumbi, S.; Kekitiinwa, A.R.; Kaudha, E.; Sarfati, T.; Musoro, G.; Nanduudu, A.; et al. Dolutegravir Dosing for Children with HIV Weighing Less than 20 Kg: Pharmacokinetic and Safety Substudies Nested in the Open-Label, Multicentre, Randomised, Non-Inferiority ODYSSEY Trial. Lancet HIV 2022, 9, e341–e352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, P.D.J.; Moore, C.L.; Mujuru, H.A.; Makumbi, S.; Kekitiinwa, A.R.; Kaudha, E.; Parker, A.; Musoro, G.; Nanduudu, A.; Lugemwa, A.; et al. Simplified Dolutegravir Dosing for Children with HIV Weighing 20 Kg or More: Pharmacokinetic and Safety Substudies of the Multicentre, Randomised ODYSSEY Trial. Lancet HIV 2020, 7, e533–e544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, S.; Berenguer, J. Efficacy of Dolutegravir in Treatment-Experienced Patients: The SAILING and VIKING Trials. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2015, 33, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, J.M.; Clotet, B.; van Lunzen, J.; Lazzarin, A.; Cavassini, M.; Henry, K.; Kulagin, V.; Givens, N.; de Oliveira, C.F.; Brennan, C. Once-Daily Dolutegravir versus Darunavir plus Ritonavir for Treatment-Naive Adults with HIV-1 Infection (FLAMINGO): 96 Week Results from a Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3b Study. Lancet HIV 2015, 2, e127–e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboud, M.; Kaplan, R.; Lombaard, J.; Zhang, F.; Hidalgo, J.A.; Mamedova, E.; Losso, M.H.; Chetchotisakd, P.; Brites, C.; Sievers, J.; et al. Dolutegravir versus Ritonavir-Boosted Lopinavir Both with Dual Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor Therapy in Adults with HIV-1 Infection in Whom First-Line Therapy Has Failed (DAWNING): An Open-Label, Non-Inferiority, Phase 3b Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffi, F.; Rachlis, A.; Stellbrink, H.J.; Hardy, W.D.; Torti, C.; Orkin, C.; Bloch, M.; Podzamczer, D.; Pokrovsky, V.; Pulido, F.; et al. Once-Daily Dolutegravir versus Raltegravir in Antiretroviral-Naive Adults with HIV-1 Infection: 48 Week Results from the Randomised, Double-Blind, Non-Inferiority SPRING-2 Study. Lancet 2013, 381, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffi, F.; Jaeger, H.; Quiros-Roldan, E.; Albrecht, H.; Belonosova, E.; Gatell, J.M.; Baril, J.-G.; Domingo, P.; Brennan, C.; Almond, S.; et al. Once-Daily Dolutegravir versus Twice-Daily Raltegravir in Antiretroviral-Naive Adults with HIV-1 Infection (SPRING-2 Study): 96 Week Results from a Randomised, Double-Blind, Non-Inferiority Trial. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokam, J.; Nka, A.D.; Mamgue Dzukam, F.Y.; Efakika Gabisa, J.; Bouba, Y.; Tommo Tchouaket, M.C.; Ka’e, A.C.; Ngoufack Jagni Semengue, E.; Takou, D.; Moudourou, S.; et al. Viral Suppression in the Era of Transition to Dolutegravir-Based Therapy in Cameroon: Children at High Risk of Virological Failure Due to the Lowly Transition in Pediatrics. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023, 102, e33737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djiyou, A.B.D.; Penda, C.I.; Madec, Y.; Ngondi, G.D.; Moukoko, A.; Varloteaux, M.; de Monteynard, L.-A.; Moins, C.; Moukoko, C.E.E.; Aghokeng, A.F. Viral Load Suppression in HIV-Infected Adolescents in Cameroon: Towards Achieving the UNAIDS 95% Viral Suppression Target. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitsky, V.; Gaolathe, T.; Mmalane, M.; Moyo, S.; Chakalisa, U.; Yankinda, E.K.; Marukutira, T.; Holme, M.P.; Sekoto, T.; Gaseitsiwe, S.; et al. Lack of Virological Suppression Among Young HIV-Positive Adults in Botswana. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2018, 78, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsondai, P.R.; Sohn, A.H.; Phiri, S.; Sikombe, K.; Sawry, S.; Chimbetete, C.; Fatti, G.; Hobbins, M.A.; Technau, K.; Rabie, H.; et al. Characterizing the Double-sided Cascade of Care for Adolescents Living with HIV Transitioning to Adulthood across Southern Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzosa Sánchez, A.; Jiménez De Ory, S.; Frick, M.A.; Menasalvas Ruiz, A.I.; Couceiro, J.A.; Mellado, M.J.; Bisbal, O.; Albendin Iglesias, H.; Montero, M.; Roca, C.; et al. Mortality in Perinatally HIV-Infected Adolescents After Transition to Adult Care in Spain. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biney, I.J.K.; Kyei, K.A.; Ganu, V.J.; Kenu, E.; Puplampu, P.; Manortey, S.; Lartey, M. Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence and Viral Suppression among HIV-Infected Adolescents and Young Adults at a Tertiary Hospital in Ghana. African J. AIDS Res. 2021, 20, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokam, J.; Sosso, S.M.; Yagai, B.; Billong, S.C.; Djubgang Mbadie, R.E.; Kamgaing Simo, R.; Edimo, S.V.; Nka, A.D.; Tiga Ayissi, A.; Yimga, J.F.; et al. Viral Suppression in Adults, Adolescents and Children Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy in Cameroon: Adolescents at High Risk of Virological Failure in the Era of “Test and Treat. ” AIDS Res. Ther. 2019, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, W.M.; Law, M.G.; Egger, M.; Wools-Kaloustian, K.; Moore, R.; McGowan, C.; Kumarasamy, N.; Desmonde, S.; Edmonds, A.; Davies, M.A.; et al. Global Estimates of Viral Suppression in Children and Adolescents and Adults on Antiretroviral Therapy Adjusted for Missing Viral Load Measurements: A Multiregional, Retrospective Cohort Study in 31 Countries. lancet. HIV 2021, 8, e766–e775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida Penda, C.; Zoung-Kanyi Bissek, A.-C.; Clotaire Bilong, S.; Boupda, L.-A.; Okala, C.; Atéba Ndongo, F.; Dallé Ngondi, G.; Moukoko Eboumbou, E.C.; Richard Njock, L.; Koki Ndombo, O. Impact of Therapeutic Education on the Viral Load of HIV Infected Children and Adolescents on Antiretroviral Therapy at the Douala Laquintinie Hospital, Cameroon. Int. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 10, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokam, J.; Takou, D.; Njume, D.; Pabo, W.; Santoro, M.M.; Njom Nlend, A.E.; Beloumou, G.; Sosso, S.; Moudourou, S.; Teto, G.; et al. Alarming Rates of Virological Failure and HIV-1 Drug Resistance amongst Adolescents Living with Perinatal HIV in Both Urban and Rural Settings: Evidence from the EDCTP READY-Study in Cameroon. HIV Med. 2021, 22, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonji, E.F.; van Wyk, B.; Mukumbang, F.C.; Hughes, G.D. Determinants of Viral Suppression among Adolescents on Antiretroviral Treatment in Ehlanzeni District, South Africa: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. AIDS Res. Ther. 2021, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).