1. Introduction

HZ jujube (

Ziziphus

jujuba Mill. ‘Huizao’) belongs to the Rhamnaceae family originated in Xinzheng, Henan province, China [

1]. It is a high-quality dry jujube type with obovate shape, small and thick stones, firm texture, delicate flesh, elastic and sweet, and high nutrient content [

2]. It contains numerous bioactive components, including ascorbic acid, flavonoids, phenols, nucleosides, triterpene acids, and polysaccharides [

3,

4,

5,

6]. As a result, HZ fruits have enhanced immunity, anti-aging, anti-cancer, and anti-inflammatory properties [

7]. HZ is primarily found in Xinjiang, Shaaxi, Hebei, and Shanxi provinces in China (

https://www.huaon.com/channel/trend/869706.html). Along with people’s interest in functional foods, planting area and yield in China are increasing, with a 2021 production of 7.73 million tons, 49.3% of which will come from Xinjiang [

8]. Thus, quality assessment is critical for the jujube industry’s long-term and healthy development.

HZ outperforms other dried jujube types due to its distinct flavor and beneficial components. So far, jujube research has primarily focused on fruit growth [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], extending the storage duration of fresh jujube [

14,

15,

16], studying the mechanism of ‘Zaofeng’ sickness [

17,

18], and developing functional components [

19,

20] et al. However, there have been few studies on the features of fruit texture in different production areas, as well as the evaluation of texture quality in HZ fruits [

21]. Furthermore, many studies have shown a relationship between soil nutrients, meteorological factors, and fruit intrinsic quality (sugar, acid) [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. However, few studies have focused on climate and soil changes in different production areas, which may lead to differences in jujube texture quality.

Texture is one of the three major acceptability aspects of food (appearance, flavor, and texture) [

27,

28], consisting mostly of hardness, adhesiveness, cohesiveness, springiness, gumminess, and chewiness [

29], and is often assessed using sensory or instrumental methods [

30]. Texture profile analysis (TPA), also referred to as the Double Mastication test [

31]. TPA can simulate mastication in the human oral cavity using various probes. It then obtains the relevant texture parameters via secondary compression and texture model [

32,

33]. TPA is commonly employed in the investigation of fruit texture features [

34], including apple [

35,

36], pear [

37], peach [

38,

39] and jujube [

40,

41] et al. As Xinjiang province’s largest main producing area of HZ fruits, the full evaluation of fruit texture quality has yet to be accomplished, and there are few related reports.

This study examined six texture indices of ‘Huizao’ jujube (HZ) fruits: hardness, chewiness, adhesiveness, cohesiveness, springiness, and gumminess in samples from four major HZ producing areas in Southern Xinjiang (Aksu, Kashi, Hotan, and Bazhou). This study has three main objectives: 1) to learn about the texture quality of HZ and how it differs from other main producing areas; 2) to find out how various texture quality indices work together and to screen the core indices for a thorough assessment of HZ fruit texture quality; and 3) to set up a model for evaluating quality and scoring HZ fruit in Xinjiang. This study gives theoretical direction for screening the superior producing locations and regional production of HZ in southern Xinjiang.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Fruit Samples

The sampling stations included 109 jujube orchards from 31 production areas spread throughout four major producing areas: Aksu (28 orchards), Kashi (25 orchards), Hotan (29 orchards), and Bazhou (27 orchards). The orchards were chosen based on the planting area of the native jujube. At the crisp maturity stage, 50 HZ fruits with good shape and smooth surfaces, without diseases, pests, and mechanical damage, were collected at random from each orchard in a different direction. The fruits were kept at low temperatures and sent to Tarim University’s laboratory in Alar, China. The samples were kept in a refrigerator at 4°C after being removed from the field. For the texture test, 30 fruits were chosen at random from each orchard’s sample, for a total of 3,270.

2.2. Determination of Texture Indices

TMS-PRO (FTC, USA) was used to assess the texture of jujube fruit. The texture analyzer parameters were established in accordance with Zhao et al [

32] and Ma et al [

42]. The force induction element had a range of 400 N, a recovery height of 40 mm, a 25% deformation, a detection speed of 50 mm/min, a starting force of 0.5 N, and 10 fruits were tested in each group.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

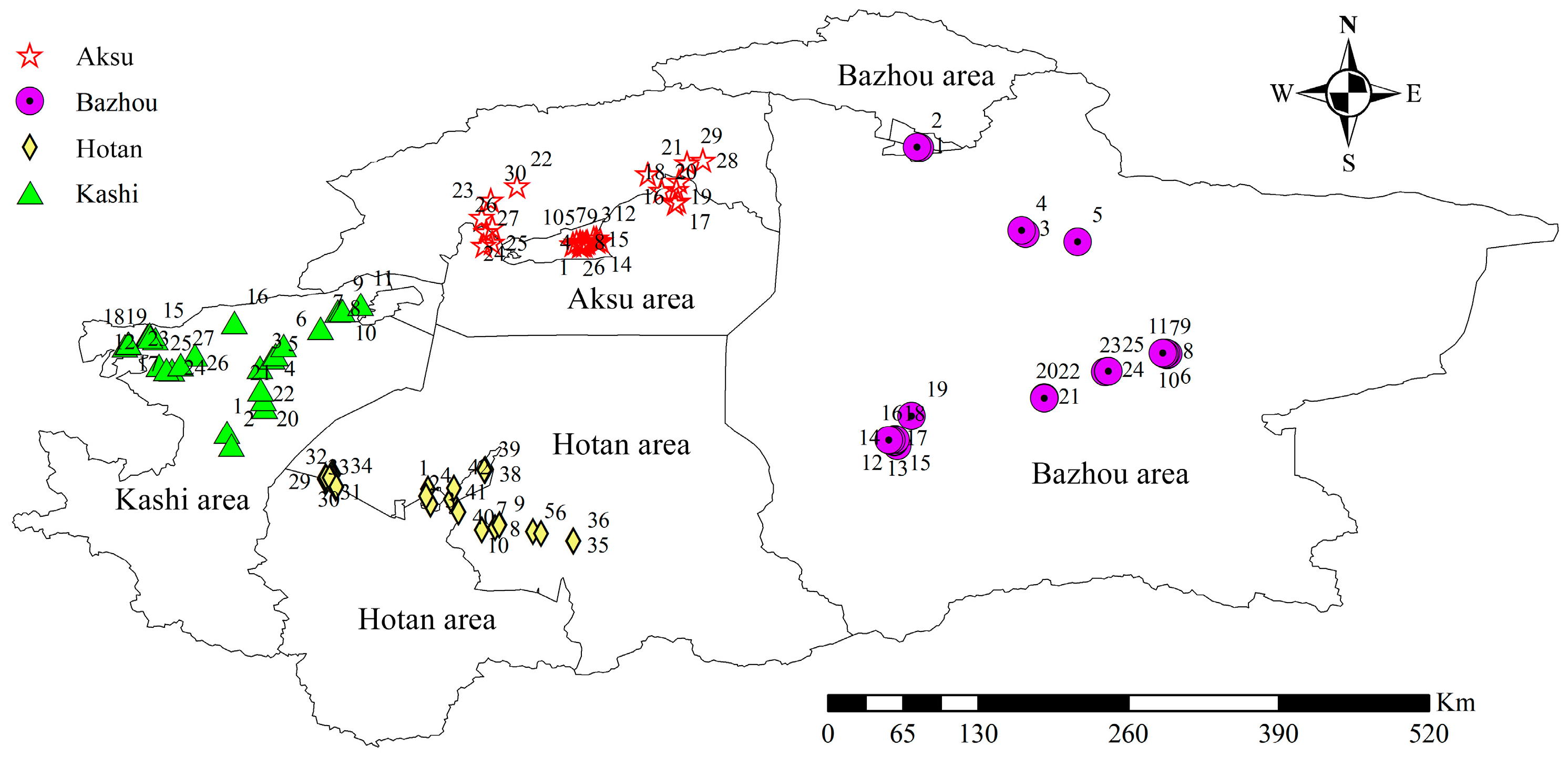

Using GPS to precisely locate the longitude and latitude of the sample points and establish records (Table S1), the sample point distribution map is drawn in ArcGIS 10.8, as shown in

Figure 1. Results were presented as mean ± SD (

P < 0.05). Excel 2019 and SPSS 29.0 (IBM, USA) were used to perform data statistics and variance analysis. Pearson correlation analysis, clustering analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) were performed using Originpro. The Z-score approach is used to normalize texture index data. The publication formula is Z = (x - µ)/ σ; Z is the Z-score value, x is the individual observation, σ is the standard deviation of the population data and μ is the mean of the population mean [

43]. Redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed to investigate the association between HZ fruit texture quality and environmental parameters in CANOCO 5.0 zones [

44,

45]. Table S2 shows meteorological data obtained from the National Geographic Information Cloud Platform (

https://www.tianditu.gov.cn).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Comparison of Texture Quality Indices of HZ Fruits from Different Main Producing Areas

Texture quality has a direct impact on the flavor of fruit [

46], and it is a prerequisite for quality classification to clarify characteristic distribution.

Tables S3 (Bazhou),

Tables S4 (Hotan),

Tables S5 (Kashi), and

Tables S6 (Aksu) indicate the textural qualities of HZ fruits from the four producing areas.

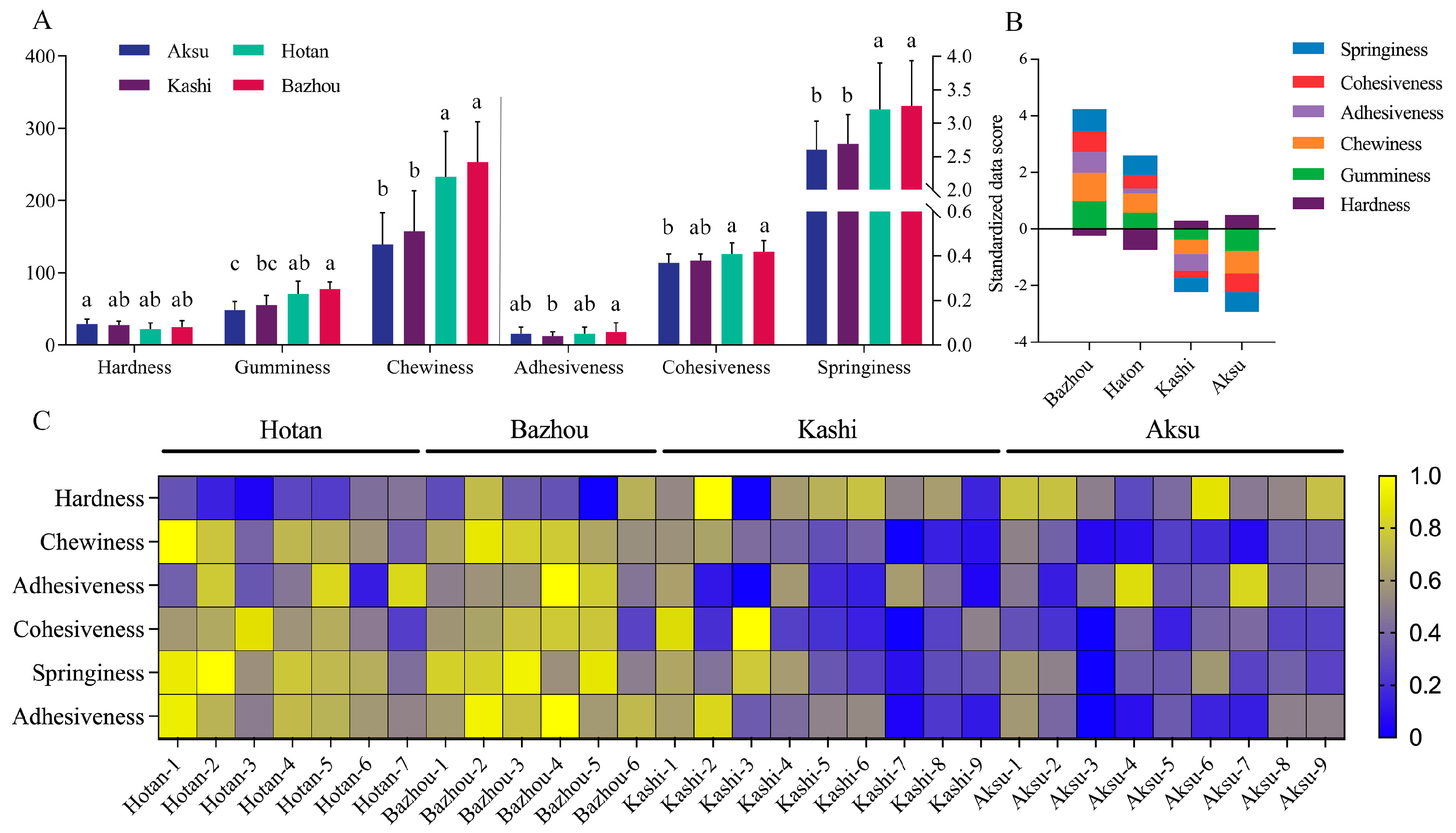

Figure 2A shows the differences in hardness, gumminess, chewiness, adhesiveness, cohesiveness, and springiness among HZ fruits from various production sites. There were no significant differences in hardness and adhesiveness between the four places, and the gumminess of the fruits in Bazhou and Hotan was much greater than that of Aksu. Bazhou and Hotan had much higher fruit chewiness and elasticity than Aksu and Kashi, as well as fruit cohesiveness, but there was no significant difference between Bazhou and Kashi. The findings indicated that Bazhou HZ fruit samples may have much superior texture quality than samples from the other three producing zones. Huang investigated the texture of HZ fruits in several producing sites in Xinjiang and found that, other from springiness, other indicators showed no variance [

21], which could be attributed to differences between years and samples.

The data for six texture indexes from four production sites were normalized and a cumulative score graph was generated (

Figure 2B). Interestingly, the fruit from Hotan and Bazhou was positive except for hardness, but the fruit from Kashi and Aksu was negative save for hardness. Grinding fruits becomes more difficult as their hardness increases [

47]. As a result, Hotan and Bazhou produce higher-quality fruit textures than Aksu and Kashi do. The interactive heat map shows the association between 31 producing areas and six texture indexes (

Figure 2C). HZ fruits from Hotan and Bazhou have less hardness than those from Kashi and Aksu, but more gumminess, chewiness, adhesiveness, cohesiveness, and springiness. The texture quality of jujube fruit is determined by a variety of elements, including geographical locations, climate conditions, orchard cultivation, and management models [

48], and differences in these parameters may influence texture quality.

3.2. Coefficient Variations of Texture Quality Indices of HZ Fruits from Different Main Producing Areas

The coefficients variation (CV) of fruit quality indices in four producing areas (

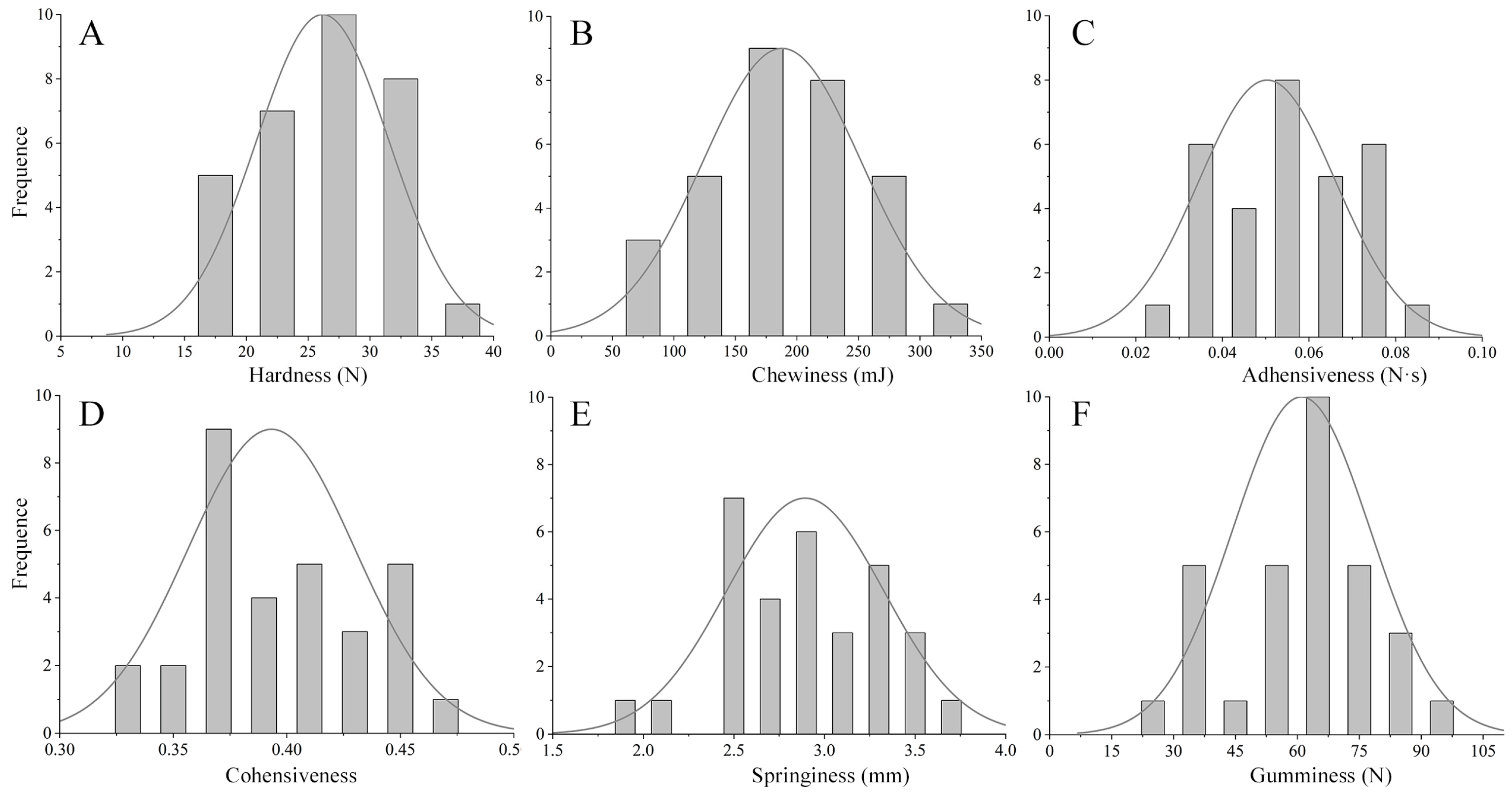

Table 1) show the degree of index variation for each texture. Fruit hardness varied slightly (13.69% in Hotan and 14.42% in Aksu), fruit chewiness, adhesiveness, and springiness varied the least (22.89%, 20.57%, and 9.69% in Bazhou, respectively), fruit cohesiveness varied the most (13.64% in Kashi), and fruit gumminess changed little (13.36% in Bazhou and 13.67% in Hotan). The Origin software was used to modify the data distribution for each texture index and plot the frequency distribution. The results are summarized in

Figure 3. All of the indicators followed a normal distribution, and the standard deviations were 5.37 (hardness), 64.35 (chewiness), 0.016 (adhesiveness), 0.037 (cohesiveness), springiness (0.43), and 16.66 (gumminess). Quality grading criteria can be constructed based on each index’s distribution function.

3.3. Probability Grading of Texture Quality Indices of HZ Fruits from Different Main Producing Areas

In this study, the sample size for index grading was 3,270, drawn from 109 HZ orchards in four major HZ producing locations, which can adequately represent the textural features of HZ fruits in Xinjiang. Each texture index of HZ fruits was classified into five grades (lower, low, medium, high, and higher) based on the normal distribution, with the 10th, 30th, 70th, and 90th percentiles. The results are presented in

Table 2. In terms of distribution proportion, middle grade samples (41.94%) had the highest proportion, while samples from lower and higher grades (9.68%) had the lowest proportion. The distribution frequency approaches theoretical probability, implying that the categorization standard is scientific and effective.

3.4. Classification of 31 HZ Producing Regions from Different Main Areas

A comprehensive evaluation cannot be conducted directly using texture quality indices for ‘HZ fruits’ due to the presence of correlations among them and the differences in index values. The data is therefore standardized. In this instance, the correlation was utilized to autonomously select the six texture quality indices that were most representative.

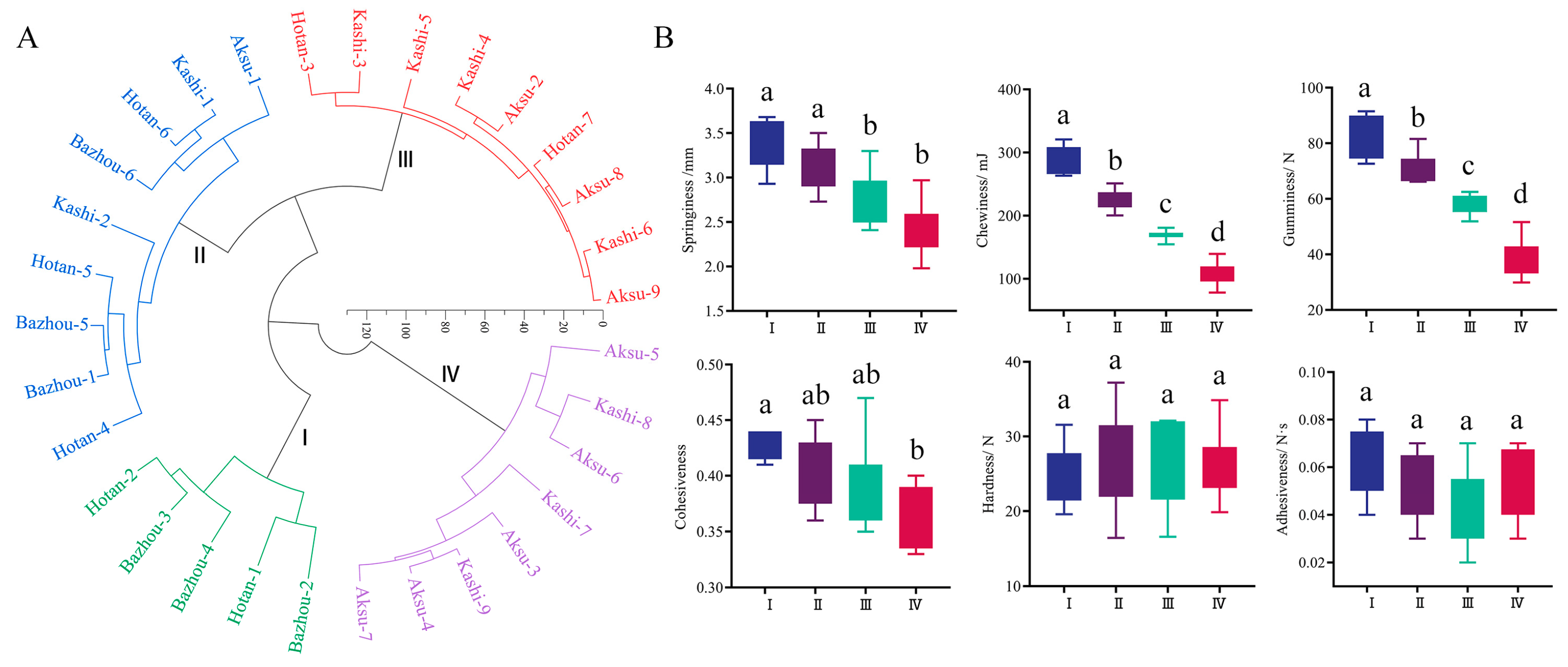

Figure 4A shows that there are 31 HZ fruit producing locations clustered into 4 categories, with each hue representing a separate category and a distance of 60. The texture quality categorizes the 31 producing areas into four groups: the first group includes the Hotan-1 and Hotan-2 areas, the Bazhou area of Bazhou-2, Bazhou-3, and Bazhou-4; the second group comprises nine areas, mostly in Hotan and Bazhou; and the third and fourth groups, with seventeen areas each, are located in Kashi and Aksu, respectively. Hotan and Bazhou were primarily classified as first and second, respectively, whilst Kashi and Aksu were classified as third and fourth. From group 1 to group 4, the four texture indexes of fruit springiness, chewiness, gumminess, and cohesiveness declined in turn, with a substantial difference, while the difference in hardness and adhesiveness was not visible (

Figure 4B).

3.5. Pearson Correlation Analysis and Clustering Analysis of Texture Quality Indices

Correlations have been identified between the fruit quality indexes [

21,

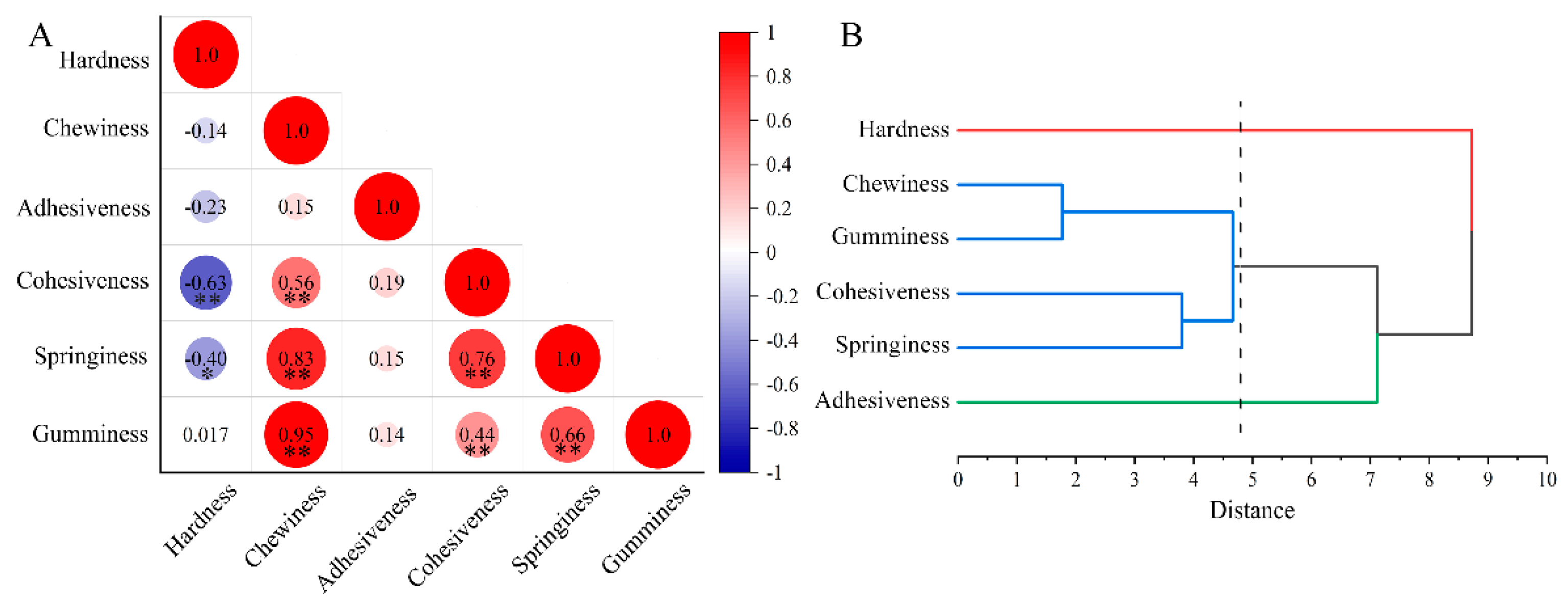

49]. A Pearson correlation study was conducted on six parameters of HZ fruits from 109 orchards. In

Figure 5A, red and blue indicate positive and negative correlations, respectively. Chewiness correlated positively (

P < 0.01) with cohesiveness, springiness, and gumminess (correlation coefficients of 0.56, 0.83, and 0.95), springiness and gumminess (correlation coefficients of 0.76 and 0.44), and gumminess (correlation coefficient of 0.66). This indicates that as chewiness increases, so do cohesiveness, springiness, and gumminess. However, hardness was significantly and negatively correlated with (

P < 0.01) and cohesiveness (

P < 0.05), with correlation coefficients of up to -0.65 and -0.40, respectively, demonstrating that the cohesiveness and springiness value decrease with increasing hardness during the fruit development of HZ fruits. There was no significant relationship between adhesiveness and other indices, indicating that they have less ability to interact with each other. The correlation analysis revealed a highly substantial positive link between chewiness, cohesiveness, springiness, and gumminess.

The data from six indices were standardized, and the correlation coefficient distance was utilized to do a Euclidean-type hierarchical clustering analysis of each index using the average approach.

Figure 5B shows a gap of 1.80 between chewiness and gumminess and 3.80 between cohesiveness and springiness. The six indices could be divided into three groups at a distance of 4.70 (indicated by the dotted line in

Figure 5B), with hardness in the first group, chewiness, gumminess, cohesiveness, and springiness in the second group and adhesiveness in the third group, which was consistent with the result of correlation analysis results.

3.6. Stepwise Repression Analysis of Texture Quality Indices

Stepwise repression was used to minimize numerous linear properties such as hardness (x

1), chewiness (x

2), cohesiveness (x

3), springiness (x

4), gumminess (x

5) and adhesiveness (x

6). All of the regression equations (y

1, y

2, y

3, y

4, and y

5) for chewiness, cohesiveness, springiness, and gumminess had R

2 values of more than 0.55, indicating that the regression model is more reliable. The

P values for the five regression equations shown above were all below 0.001, showing that they can accurately predict the hardness, chewiness, cohesiveness, springiness, and gumminess of HZ fruit texture, respectively. The y

6 has a poor R

2 and

P > 0.05, indicating that it cannot accurately predict the adhesiveness (

Table 3). This shows that the relationship between the texture indexes and measured data may overlap [

50]. As a result, screening the major texture index is more accurate for determining the quality of HZ fruits.

3.7. Principal Component Analysis of Texture Quality Indices

Based on the criteria of cumulative variance percentage greater than 85%, three principal components were chosen, which actually accounted for 92.563% of all variances, as shown in

Table 4, with the stronger the eigenvalue value, the greater the influence of the principal component [

51]. The variance contribution of principal component 1 (PC1) was 55.242%, and its representative indices were chewiness, cohesiveness, springiness, and gumminess. All of the eigenvalues were greater than 0.80, with springiness having the highest eigenvalue (0.926). Springiness may represent the chewing qualities of the flesh, as chewiness, cohesiveness, and gumminess were all extremely substantially connected (correlation values of 0.83, 0.76, and 0.66, respectively). PC2 accounted for 22.202% of the overall variance, and its representative index was hardness, with an eigenvalue of 0.802 that reflected the hardness qualities of the flesh. The variance contribution of PC3 was 15.119%, with adhesiveness serving as the typical index; the eigenvalue was 0.885, reflecting the adhesiveness features of the flesh. It has been found that springiness, hardness, and adhesiveness are major indications of the textural quality of HZ fruits. The coefficient of each texture index was produced by adding the score of the principal component of each quality index to the square root of the corresponding eigenvalue, and the expression for the scores of the three principal components was constructed as follows:

y1=-0.255x1+0.499x2+0.154x3+0.454x4+0.509x5+0.444x6;

y2=0.695x1+0.330x2-0.318x3-0.321x4+0.014x5+0.451x6;

y3=0.213x1+0.054x2+0.929x3-0.227x4-0.140x5+0.131x6;

Given that each principal component may have various variance contributions, the weight for establishing a comprehensive evaluation model was the ratio of each principal component’s variance contribution to the cumulative variance contribution. The full scoring model for HZ fruit texture quality has been established as follows: Y=0.597y

1+0.240y

2+0.163y

3.

Table 5 shows that the comprehensive scores of HZ jujube texture quality could be divided into five levels (poor, somewhat poor, medium, good, and excellent) based on the 10th, 30th, 70th, and 90th percentiles. According to a comprehensive review of HZ jujube texture quality indexes, medium grade, rather poor, good grade, excellent grade, and low grade made up 41.935%, 19.355%, 19.355%, 9.677%, and 9.677% of the total, respectively. These distribution results correspond to the theoretical likelihood, suggesting that the grading system is both practical and effective [

52].

3.8. Comprehensive Ranking of Texture Quality of 31 Producing Areas

Based on the comprehensive scoring methodology, 31 HZ fruit samples from four major producing areas were assessed separately (

Table 6). The higher the score, the superior the fruit quality [

53]. The top five producers are Bazhou-2, Hotan-1, Bahzou-4, Bazhou-3, and Hotan-2, which corresponds to the cluster analysis results. Bazhou (16.1%) and Hotan (12.9%) received good or exceptional ratings out of the 31 areas. Furthermore, the average comprehensive score of samples from the four producing areas fell in descending order: Bazhou (1.24) > Hotan (0.773) > Kashi (-0.577) > Aksu (-0.852). Overall, the texture quality of HZ fruits from the four primary production areas may be evaluated as Bazhou > Hotan > Kashi > Aksu.

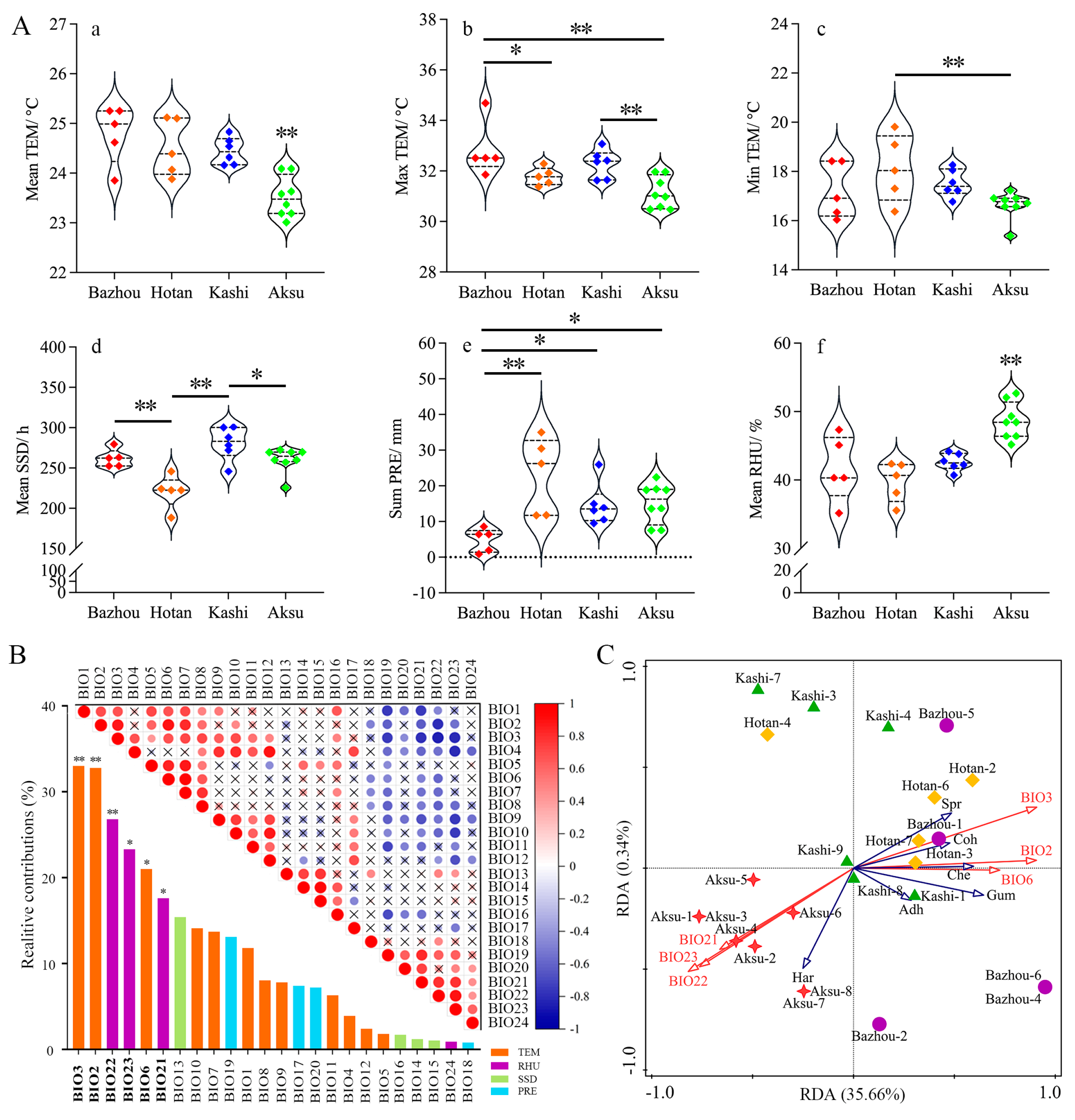

3.9. Adaptation of the Textural Quality of HZ Fruits to the Environment

Plants can undergo genetic diversification and local adaptation in response to environmental variations [

54]. There were a total of 24 meteorological data points recorded (Table S2), including the following: mean temperature (6-9 months TEM), maximum temperature (Max TEM) and minimum temperature (Min TEM), number of sunny days (6-9 months SSD), total precipitation (6-9 months PRE), relative humidity (Mean RHU), and peak fruit expansion (June to July) and pre-ripening (August to September), both of which are crucial for fruit quality formation [

13]. Climate characteristics are consistent throughout different producing areas (

Figure 6A). HZ fruits from Bazhou and Hotan had higher texture quality, with Mean TEM, Max TEM, and Min TEM temperature data grouped in the upper part of the fiddle diagram (

Figure 6Aa-c), but PRE and RHU were in the lower half of the fiddle diagram (

Figure 6Ae-f). The texture quality of HZ fruits in the Aksu producing area falls into the fourth category, while climatic data show low temperatures and high humidity. At the same time, the SSD change rule for the four production sites does not correspond to the changing trend of fruit texture quality (

Figure 6Ad). The foregoing results show that production areas with good texture quality of HZ fruits must have high temperatures, whereas too high RHU in production areas with poor texture quality is detrimental to fruit texture quality improvement.

A redundancy analysis (RDA) method was used to identify climate parameters related to texture quality metrics in HZ fruits. The variables were selected based on their prioritized contributions from RDA analysis and Pearson’s correlation

P < 0.05 (

Figure 6B). The first of the three RDA axes was statistically significant, accounting for roughly 35.66% of the variance covered by the RDA model (

Figure 6C). In various HZ fruit production zones, TEM had a considerable favorable effect on the five texture indices of gumminess, chewiness, adhesiveness, cohesiveness, and springiness, but a detrimental effect on the hardness of the fruits. Relative humidity increased the hardness of HZ apples while decreasing the other five texture indices (

Figure 6C). The revolution results can be used to determine the ideal HZ planting area and as a theoretical reference for regional HZ production.

4. Discussion

Xinjiang is a large territory, and the climate and soil conditions vary widely, resulting in the same diversity in fruit quality in different regions [

26]. Currently, evaluating fruits based on personal experience is the prevalent strategy [

55]. However, this strategy lacks an objective basis and scientific theoretical guidance [

56]. Accordingly, grading results are typically unstable and do not adequately reflect the eigenvalue’s distribution properties. As a result, researchers have developed a probability grading method that provides the advantages of objectivity, consistent criteria, and comparable outcomes [

57]. A prerequisite for quality grading is the clarification of feature distribution [

58], The variation coefficient is a measure of the degree of dispersion of the characteristics [

59], and a higher variation coefficient facilitates indexing grading [

60]. The variation coefficients of six texture indices were high in the current investigation, ranging from 5.25% to 38.02%. The six indices were ranked according to their probability. The texture indexes of Bazhou and Hotan were significantly different from those of Kashi and Aksu, as evidenced by the comparison of the texture quality of HZ produce in four producing areas. Meanwhile, the primary determinants of fruit texture quality among the four production areas are disparities in springiness, chewiness, gumminess, and cohesiveness, which are classified according to the texture quality of the 31 producing areas. This is consistent with the results of prior investigations on the textural properties of gray jujube winter [

25] and winter jujube [

52].

Because of the texture index relationship, the measured data may overlap [

50]. As a result, screening the major texture index is a more accurate way to measure HZ quality. The comprehensive score showed that Bazhou samples outperformed samples from all other major producing areas. Climate conditions and orchard management level are the main factors determining the quality of ‘winter’ jujube [

48]. As a result, we looked into the relationship between climate characteristics and texture quality across multiple production areas. It was found that the differences in texture indices of HZ fruits in four major production areas were connected to TEM and RHU, which is consistent with the findings of the study on the association between the texture quality of ‘Junzao’ jujube and climate parameters [

61]. This could be owing to the fact that the four primary producing sites are located on the fringe of the Taklamakan Desert, where precipitation changes are not immediately apparent. The revaluation results can be utilized to determine the ideal huizao planting area and serve as a theoretical reference for regional HZ production.

Overall, the texture quality characteristics of HZ fruits from various producing locations were revealed, which is extremely important for selecting high-quality HZ fruit producing areas. In the HZ industry, the established assessment model of HZ fruits may be used to completely analyze the texture quality of HZ fruits, as well as to pick more suitable sites for HZ growth based on the climatic conditions. As a result, the findings of this study contribute to the assessment of the textural quality of HZ fruits and the premium region selection of HZ in various producing areas. However, additional study is required for the future development of the HZ business.

5. Conclusions

This study assessed the six texture indicators of HZ fruits from 109 orchards in four major HZ producing locations in Southern Xinjiang. The relationship inquiry revealed that HZ fruits from Bazhou have a better texture quality than those from the other three producing sites. Furthermore, using principal component analysis, springiness hardness and adhesiveness are essential indices for assessing the texture quality of HZ fruits. Higher temperature and lower relative humidity were more successful at improving the texture of HZ fruits. According to the comprehensive score, the texture quality of HZ fruits from the four major production areas is in the following order: Bazhou > Hotan > Kashi > Aksu.

Authors contribution

Tianfa Guo: Sampling, Investigation, Analysising data, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review and editing. Qianqian Qiu: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review and editing. Chuanjiang Zhang: Investigation, Data Analysis. Xiangyu Li: Investigation, Data Analysis. Cuiyun Wu: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing - review and editing. Zhenlei Wang: Investigation, Formal analysis. Minjuan Lin: Investigation. Shuangquan Jing: Financial support. Xingang Li: Modification. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Special Fund Project of Xinjiang Jujube Industry Technology System (No. XJCYTX-01), Agricultural Sciences Research Institute of Kunyu “Establishment of Standardized Garden and Standard System for Jujube” (No. 2021011), and the Demonstration Base for Cultivating Innovative Talents in Horticulture Industry (No. 2019CB001). The authors would like to express their gratitude to EditSprings (

https://www.editsprings.cn) for the expert linguistic services provided.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Li, D.; Niu, X.; Tian, J. Chinese jujube variety resource map: Beijing: China Agricultural Press; 2013.

- Qu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Peng, S.; Guo, Y. Chinese Fruit Trees. Jujube: Chinese Forestry Press; 1993.

- Agrawal, P.; Singh, T.; Pathak, D.; Chopra, H. An updated review of Ziziphus jujube: major focus on its phytochemicals and pharmacological properties. Pharmacological Research-Modern Chinese Medicine 2023, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Maaiden, E.; El Kharrassi, Y.; Qarah, N.A.; Essamadi, A.K.; Moustaid, K.; Nasser, B. Genus Ziziphus: A comprehensive review on ethnopharmacological, phytochemical and pharmacological properties. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2020, 259, 112950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Duan, J.-A.; Qian, D.; Tang, Y.; Wu, D.; Su, S.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y. Content variations of triterpenic acid, nucleoside, nucleobase, and sugar in jujube (Ziziphus jujuba) fruit during ripening. Food Chemistry 2015, 167, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, T.; Ruan, K.; Xu, H.; Liu, H.; Tang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Duan, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, M.; Song, Z. Effect of different drying methods on the drying characteristics, chemical properties and antioxidant capacity of Ziziphus jujuba var. Spinosa fruit. LWT 2024, 196, 115873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Wu, C.; Wang, M. The jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) fruit: a review of current knowledge of fruit composition and health benefits. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2013, 61, 3351–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.; Sun, W.; Wang, T. Overview of Geographical Indication of Chinese Jujube and Development of Ancient Jujube Tree Resources in Yellow River Basin. Journal of Fruit Tree Resources 2023, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Li, X. Transcript analyses of ethylene pathway genes during ripening of Chinese jujube fruit. Journal of Plant Physiology 2018, 224-225, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Lian, Q.; Fu, P.; He, Y.; Qiao, J.; Xu, K.; Liu, L.; Wu, M.; et al. Genomic analyses of diverse wild and cultivated accessions provide insights into the evolutionary history of jujube. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2021, 19, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Li, S.; Shao, P.; Yu, Q.; Wang, J.; Xu, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Comparative population genomics dissects the genetic basis of seven domestication traits in jujube. Horticulture Research 2020, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Du, J.; Zhu, D.; Li, X.; Li, X. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses of anthocyanin biosynthesis mechanisms in the color mutant Ziziphus jujuba cv. Tailihong. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2020, 68, 15186–15198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhao, H.; Hou, L.; Zhang, C.; Bo, W.; Pang, X.; Li, Y. HPLC-MS/MS-based and transcriptome analysis reveal the effects of ABA and MeJA on jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) cracking. Food Chemistry 2023, 421, 136155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Wu, C.; Kou, X.; Xue, Z. Glycine betaine inhibits postharvest softening and quality decline of winter jujube fruit by regulating energy and antioxidant metabolism. Food Chemistry 2023, 410, 135445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Xu, Y.; Han, X.; Bao, N.; Sheng, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Luo, Z. Elevated O2 alleviated anaerobic metabolism in postharvest winter jujube fruit by regulating pyruvic acid and energy metabolism. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2023, 203, 112397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Kou, X.; Wu, C.; Fan, G.; Li, T.; Li, X.; Zhou, D.; Yan, Z.; Zhu, J. Recent advances and development of postharvest management research for fresh jujube fruit: A review. Scientia Horticulturae 2023, 310, 111769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Gu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tan, B.; Zheng, X.; Ye, X.; Cheng, J.; Wang, W.; Bi, S. Jujube witches’ broom (‘Zaofeng’) disease: bacteria that drive the plants crazy. Fruit Research 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Chen, L.; Ye, X.; Tan, B.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, J.; Wang, W.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Phytoplasma effector Zaofeng6 induces shoot proliferation by decreasing the expression of ZjTCP7 in Ziziphus jujuba. Horticulture Research 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, R.; Fu, C.; Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Han, G.; Zhang, J. Combining bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity profiling provide insights into assessment of geographical features of Chinese jujube. Food Bioscience 2022, 46, 101573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Guo, S.; Ren, X.; Du, J.; Bai, L.; Cui, X.; Ho, C.-T.; Bai, N. Simultaneous quantification of 18 bioactive constituents in Ziziphus jujuba fruits by HPLC coupled with a chemometric method. Food Science and Human Wellness 2022, 11, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhao, W.; Sun, J.; Wan, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Yang, Z.; Ma, L.; Lu, C.; et al. Texture analysis of Hui jujube and Jun jujube in different production areas of Xinjiang. Non-wood Forest Research 2022, 40, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, S.; Sun, J.; Wang, L.; Huguo, Z.; Yu, T.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, J. Jujube fruit quality and its response to environment factors in Xinjiang different plantation areas. Non-wood Forest Research 2023, 41, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; Huang, J.; Loiu, C.; Zan, Y. Effects of climate factors on the quality of gray jujube. Hubei Agricultural Sciences 2022, 61, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, W.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, M.; Wei, X.; Yang, Z.; Ma, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; et al. Canonical correlation analysis of soil nutrients and fruit quality in Junzao orchard. Non-wood Forest Research 2021, 39, 104–114+122. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, W.; Wang, C.; Li, X. Superior production region of Chinese jujube in Xinjiang. Journal of Fruit Science 2015, 32, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Huang, J.; Gao, W. A study on high-quality production regions of dry Chinese jujube in China. Journal of Fruit Science 2005, 22, 620–625. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, M. Relation between texture and mastication. Journal of Texture Studies 2004, 35, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z. Quality Analysis of Horticultural Products: China Agricultural Press; 2011.

- Pham, Q.T.; Liou, N.-S. Investigating texture and mechanical properties of Asian pear flesh by compression tests. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology 2017, 31, 3671–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, T.; Guerrero, L.; Gratacós-Cubarsí, M.; Claret, A.; Argyris, J.; Garcia-Mas, J.; Hortós, M. Textural properties of different melon (Cucumis melo L.) fruit types: Sensory and physical-chemical evaluation. Scientia Horticulturae 2016, 201, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chen, Y.; Jin, B. Detection of texture properties of kiwi fruits by texture profile analysis and simulation of manual chewing. Science and Technology of Food Industry 2010, 31, 146–148,152. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, A.; Xue, X.; Wang, Y.; Ren, H.; Gong, G.; Jiao, J.; Sui, C.; Li, D. Measuring texture quality of fresh jujube fruit using texture analyser. Journal of Fruit Science 2018, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Opara, U.L. Approaches to analysis and modeling texture in fresh and processed foods – A review. Journal of Food Engineering 2013, 119, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contador, L.; Shinya, P.; Infante, R. Texture phenotyping in fresh fleshy fruit. Scientia Horticulturae 2015, 193, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Guan, Y. Prediction of Storage Quality of ‘Hanfu’ Apple Based on Texture Properties. Food Science 2012, 33, 335–338+335. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Xiao, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Cong, P.; Tian, Y. Study on texture properties of apple flesh by using texture profile analysis. Journal of Fruit Science 2014, 31, 977–985. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Jia, Y.; Wei, J.; Ran, X.; Le, W. Studies on the post-harvested fruit texture changes of ‘Yali’and ‘Jingbaili’pears by using texture analyzer. Acta Horticulturae Sinica 2012, 39, 1359. [Google Scholar]

- Contador, L.; Díaz, M.; Hernández, E.; Shinya, P.; Infante Espiñeira, R. The relationship between instrumental tests and sensory determinations of peach and nectarine texture. European Journal of Horticultural Science 2016, 81, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofi, M.; Mourtzinos, I.; Lazaridou, A.; Drogoudi, P.; Tsitlakidou, P.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Manganaris, G.A. Elaboration of novel and comprehensive protocols toward determination of textural properties and other sensorial attributes of canning peach fruit. Journal of Texture Studies 2021, 52, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Z. Evaluation and cluster analysis of Jujube fruit texture based on TPA method. Xinjiang Agricultural Sciences 2019, 56, 1860–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Shi, Q. Optimization of determining the textural properties of winter jujube in south Xinjiang by TPA. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences 2014, 42, 5947–5949. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.; Wang, G.; Liang, L. Establishment of the Detecting Method on the Fruit Texture of Dongzao by Puncture Test. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 2011, 44, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, D.; Liu, B.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, H. Stacking Ensemble Learning Modeling and Forecasting of Maize Yield Based on Meteorological Factors. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 2024, 57, 679–697. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Liu Xa Peng, P.; Ma, Z.; Guo, H. Relationship Between Folicles and Seeds Traits of Paeonia decomposita and Environment Factors. Journal of Northeast Forestry University 2018, 46, 41–45+58. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Döring, T.F.; Zhao, X.; Weiner, J.; Dang, P.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Schmid, B.; Qin, X. Cultivar mixtures increase crop yields and temporal yield stability globally. A meta-analysis. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2024, 44, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Li, R.; Peng, S.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Y.; Li, J. Comparison and Evaluation of Fruit Quality of Five Pineapple Cultivars. Food Research and Development 2022, 43, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zuo, T.; Yi, H.; Yu, B.; Wei, Z.; Pan, H. Qantitative evaluation of Valencia orange mastication degree using texture properties detected by instrument. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 2014, 30, 265–271. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Q.; Han, G.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Jia, Y.; Li, X. Nutrient composition and quality traits of dried jujube fruits in seven producing areas based on metabolomics analysis. Food Chemistry 2022, 385, 132627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Du, J.; Wang, C.; Shi, X.; Wang, B. Analysis of physicochemical characteristics, antioxidant activity, and key aroma compounds of five flat peach cultivars grown in Xinjiang. LWT 2023, 176, 114550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Liu, D.; Shao, Q.; Gao, G.; Qi, H. Analysis and comprehensive evaluation of textural quality of ripe fruits from different varieties of oriental melon (Cucumis melo var. makuwa Makino). Shipin Kexue/Food Science 2019, 40, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, J.; Song, K.; Jiang, X.; Gao, W.; Zhang, C.; Feng, G. Evaluation and selection of main characters of oil peony ‘Feng Dan’ based on principal component analysis. Journal of Tianjin Agricultural University 2021, 28, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Xu, M.; Wan, H.; Han, L.; Liu, X.; Li, Q.; Hao, B.; Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Development of a texture evaluation system for winter jujube (Ziziphus jujuba ‘Dongzao’). Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2022, 21, 3658–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Fan, J.; Li, D.; Zhon, Y.; Guo, Y.; Biting, J.; Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Guoming, F. Evaluation of processing qualities of different mulberry varieties. Food and Fermentation Industries 2020, 46, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muellner-Riehl, A.N. Mountains as Evolutionary Arenas: Patterns, Emerging Approaches, Paradigm Shifts, and Their Implications for Plant Phylogeographic Research in the Tibeto-Himalayan Region. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Tong, H.; Du, S. Sensory evaluation of food: China Forestry Press; 2016.

- Zhu, D.; Li, H.; Cao, X.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Meng, X. Research Progress in Quality Evaluation of Fresh Foods by Texture Analyzers. Food Science 2014, 35, 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. Studies on the variations and grading standards of several economid characters of peach. Journal of Beijing Agricultural College 1992, 7, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Xu, M.; Wang, K.; Chen, Q.; Han, L.; Li, Q.; Guo, Q.; Wan, H.; Nie, J. Development of a comprehensive evaluation system for the sensory and nutritional quality of winter jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill. cv. Dongzao). LWT 2024, 194, 115777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, G.; Fang, W. The evaluating criteria of some fruit quantitative characters of peach (Prunus persica L.) genetic resources. Acta Horticulturae Sinica 2005, 32, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Nie, J.; Li, M.; Kang, Y.; Kuang, L.; Ye, M. Study on screening of taste evaluation indexes for apple. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 2015, 48, 2796–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; He, B.; Ma, S.; Zhang, M.; Wei, X.; Song, J.; Liu, W.; Li, J. Texture quality of Ziziphus jujuba cv. junzao of Tarim Basin and its relationship with meteorological factors. Journal of Northwest A & F University(Natural Science Edition) 2021, 49, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Distribution map of sample points in the main producing areas of HZ fruits. (☆, ⊙, ◇ and △ represents Aksu, Bazhou, Hotan and Kashi, respectively.).

Figure 1.

Distribution map of sample points in the main producing areas of HZ fruits. (☆, ⊙, ◇ and △ represents Aksu, Bazhou, Hotan and Kashi, respectively.).

Figure 2.

The difference in textural quality of HZ fruits throughout four production areas. (A) Significant differences in six indices (P < 0.05); (B) Standardized texture score; (C) Interactive heatmap of 31 producing areas and texture quality indicators.

Figure 2.

The difference in textural quality of HZ fruits throughout four production areas. (A) Significant differences in six indices (P < 0.05); (B) Standardized texture score; (C) Interactive heatmap of 31 producing areas and texture quality indicators.

Figure 3.

Six textural indicators of HZ fruits were distributed normally throughout four production areas. (A) hardness; (B) chewiness; (C) adhesiveness; (D) cohesiveness; (E) springiness; and (F) gumminess.

Figure 3.

Six textural indicators of HZ fruits were distributed normally throughout four production areas. (A) hardness; (B) chewiness; (C) adhesiveness; (D) cohesiveness; (E) springiness; and (F) gumminess.

Figure 4.

31 producing areas were clustered. (A) Cluster analysis was used to examine texture quality in 31 producing regions (Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, Ⅳ indicate four groups). (B) Four groups of HZ fruits were analyzed for texture quality (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

31 producing areas were clustered. (A) Cluster analysis was used to examine texture quality in 31 producing regions (Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, Ⅳ indicate four groups). (B) Four groups of HZ fruits were analyzed for texture quality (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Relationship analysis of six texture indexes of HZ fruits. (A) Pearson correlation heatmap of six indices (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01); (B) Dendrogram of six texture indices.

Figure 5.

Relationship analysis of six texture indexes of HZ fruits. (A) Pearson correlation heatmap of six indices (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01); (B) Dendrogram of six texture indices.

Figure 6.

An overview of meteorological data from different regions. (A) Comparison of meteorological parameters of 6-9 months in four HZ producing locations (a: mean temperature (TEM); b: maximum temperature (TEM); c: minimum temperature (TEM); d: sun shine day (SSD); e: precipitation (PRE); f: relative humidity (RHU)). (B) Pearson’s correlation (above the diagonal) and contribution ranking (below the diagonal; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01) for 24 climate variables. The bold variables identify the six climate variables selected for RDA analysis; (C) PCA figure using RDA axes 1 and 2.

Figure 6.

An overview of meteorological data from different regions. (A) Comparison of meteorological parameters of 6-9 months in four HZ producing locations (a: mean temperature (TEM); b: maximum temperature (TEM); c: minimum temperature (TEM); d: sun shine day (SSD); e: precipitation (PRE); f: relative humidity (RHU)). (B) Pearson’s correlation (above the diagonal) and contribution ranking (below the diagonal; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01) for 24 climate variables. The bold variables identify the six climate variables selected for RDA analysis; (C) PCA figure using RDA axes 1 and 2.

Table 1.

The variations degree of six texture indices in four producing areas.

Table 1.

The variations degree of six texture indices in four producing areas.

| Area |

Statistic |

Hardness /N |

Chewiness/ mJ |

Adhesiveness/ N·s |

Cohesiveness |

Springiness /mm |

Gumminess /N |

| Hotan |

Max value |

22.15 |

233.21 |

0.05 |

0.41 |

3.21 |

70.61 |

| Min value |

25.79 |

320.85 |

0.07 |

0.45 |

3.68 |

87.46 |

| Mean value |

17.29 |

168.31 |

0.03 |

0.37 |

2.71 |

59.65 |

| SD |

3.03 |

53.39 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

0.33 |

9.43 |

| CV /% |

13.69 |

22.89 |

31.17 |

6.49 |

10.36 |

13.36 |

| Bazhou |

Max value |

24.78 |

253.30 |

0.06 |

0.42 |

3.26 |

77.34 |

| Min value |

31.56 |

296.27 |

0.08 |

0.44 |

3.59 |

91.49 |

| Mean value |

16.45 |

211.80 |

0.05 |

0.37 |

2.81 |

66.53 |

| SD |

5.62 |

31.50 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

0.32 |

10.57 |

| CV /% |

22.69 |

12.43 |

20.57 |

6.53 |

9.69 |

13.67 |

| Kashi |

Max value |

27.65 |

157.44 |

0.04 |

0.38 |

2.69 |

55.00 |

| Min value |

37.22 |

173.40 |

0.06 |

0.40 |

3.00 |

62.52 |

| Mean value |

19.85 |

78.08 |

0.03 |

0.33 |

2.14 |

32.41 |

| SD |

6.21 |

51.32 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

0.37 |

15.49 |

| CV /% |

22.46 |

32.60 |

38.02 |

12.41 |

13.64 |

28.16 |

| Aksu |

Max value |

28.76 |

139.53 |

0.05 |

0.37 |

2.60 |

48.55 |

| Min value |

34.86 |

167.83 |

0.07 |

0.39 |

2.97 |

60.82 |

| Mean value |

25.10 |

95.47 |

0.04 |

0.35 |

2.44 |

38.26 |

| SD |

4.15 |

38.13 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.31 |

12.99 |

| Coefficient of variation /% |

14.42 |

27.33 |

27.32 |

5.25 |

12.00 |

26.76 |

Table 2.

Probability grading of texture indices and the sample proportion of each grade.

Table 2.

Probability grading of texture indices and the sample proportion of each grade.

| Index |

Grade |

Lower |

Low |

Medium |

high |

higher |

| hardness |

Standard (N) |

<17.76 |

17.76 ~ 23.01 |

23.02 ~ 29.75 |

29.76 ~ 32.23 |

>32.23 |

| |

Proportion (%) |

9.68 |

19.36 |

41.94 |

19.36 |

9.68 |

| chewiness |

Standard (mJ) |

<97.09 |

97.09 ~ 160.14 |

160.15 ~ 231.96 |

231.97 ~ 273.09 |

>273.10 |

| |

Proportion (%) |

9.68 |

19.36 |

41.94 |

19.36 |

9.68 |

| adhesiveness |

Standard (N·s) |

<0.029 |

0.03 ~ 0.04 |

0.05 ~ 0.06 |

0.061 ~ 0.07 |

>0.07 |

| |

Proportion (%) |

22.58 |

12.90 |

41.94 |

19.36 |

3.23 |

| cohesiveness |

Standard |

<0.36 |

0.36 ~ 0.37 |

0.38 ~ 0.41 |

0.42 ~ 0.45 |

>0.45 |

| |

Proportion (%) |

12.90 |

29.03 |

29.03 |

19.36 |

9.68 |

| springiness |

Standard (mm) |

<2.43 |

2.43 ~ 2.59 |

2.60 ~ 3.15 |

3.16 ~ 3.52 |

>3.52 |

| |

Proportion (%) |

9.68 |

19.36 |

41.94 |

19.36 |

9.68 |

| gumminess |

Standard (N) |

<35.92 |

35.92 ~ 53.53 |

53.54 ~ 69.96 |

69.97 ~ 86.28 |

>86.28 |

| |

Proportion (%) |

9.68 |

19.36 |

41.94 |

19.36 |

9.68 |

Table 3.

Results of stepwise regression among indices of HZ fruits texture quality.

Table 3.

Results of stepwise regression among indices of HZ fruits texture quality.

| Dependent variable |

Regression |

R2

|

F |

P-value |

| Hardness (x1) |

y1=54.532-109.815x3+0.385x5

|

0.556 |

6.510 |

<0.001 |

| Chewiness (x2) |

y2=58.328x4+2.837x5

|

0.973 |

177.012 |

<0.001 |

| Cohesiveness (x3) |

y3=0.267+0.075x4-0.003x1

|

0.751 |

14.465 |

<0.001 |

| Springiness (x4) |

y4=-0.026x5+0.011x2+4.491x3

|

0.890 |

38.702 |

<0.001 |

| Gumminess (x5) |

y5=0.449x1+0.32x2-15.94x4

|

0.952 |

94.507 |

<0.001 |

| Adhesiveness (x6) |

y6=0.08-0.001x1-0.028x3-0.001x4

|

0.082 |

0.430 |

0.823 |

Table 4.

Principal component analysis of HZ fruits texture quality.

Table 4.

Principal component analysis of HZ fruits texture quality.

| Index |

PC1 |

PC2 |

PC3 |

| Hardness (x1) |

-0.464 |

0.802 |

0.203 |

| Chewiness (x2) |

0.909 |

0.381 |

0.051 |

| Adhesiveness (x3) |

0.281 |

-0.367 |

0.885 |

| Cohesiveness (x4) |

0.826 |

-0.371 |

-0.216 |

| Springiness (x5) |

0.926 |

0.016 |

-0.133 |

| Gumminess (x6) |

0.808 |

0.520 |

0.125 |

| Eigenvalue |

3.315 |

1.332 |

0.907 |

| Variance contribution (%) |

55.242 |

22.202 |

15.119 |

| Percent of variance (%) |

55.242 |

77.444 |

92.563 |

Table 5.

Probability grading of comprehensive score of HZ fruits texture indices.

Table 5.

Probability grading of comprehensive score of HZ fruits texture indices.

| Grade |

Poor |

Relatively poor |

Medium |

Good |

Excellent |

| Comprehensive score |

<-1.480 |

-1.479 ~ (-0.728) |

-0.727 ~ 0.780 |

0.781 ~ 1.700 |

>1.700 |

| Sample |

3 |

6 |

13 |

6 |

3 |

| Proportion (%) |

9.677 |

19.355 |

41.935 |

19.355 |

9.677 |

Table 6.

Ranking of comprehensive score of HZ fruits core texture quality.

Table 6.

Ranking of comprehensive score of HZ fruits core texture quality.

| Regions |

y1 score |

y2 score |

y3 score |

Comprehensi-ve score |

Rank |

Regions |

y1 score |

y2 score |

y3 score |

Comprehens-ive score |

Rank |

| Bazhou-2 |

2.29 |

1.58 |

0.77 |

1.87 |

1 |

Kashi-4 |

-0.45 |

0.15 |

0.73 |

-0.11 |

17 |

| Hotan-1 |

2.73 |

1.1 |

-0.71 |

1.78 |

2 |

Hotan-7 |

-0.44 |

-0.34 |

1.33 |

-0.13 |

18 |

| Bazhou-4 |

2.49 |

-0.14 |

1.64 |

1.72 |

3 |

Aksu-8 |

-0.87 |

0.2 |

0.23 |

-0.43 |

19 |

| Bazhou-3 |

2.68 |

-0.01 |

0.16 |

1.62 |

4 |

Aksu-9 |

-1.26 |

0.84 |

0.48 |

-0.47 |

20 |

| Hotan-2 |

2.66 |

-0.75 |

0.63 |

1.51 |

5 |

Aksu-2 |

-1.27 |

1.2 |

-0.8 |

-0.6 |

21 |

| Bazhou-5 |

2.45 |

-1.66 |

0.37 |

1.13 |

6 |

Kashi-6 |

-1.67 |

1.5 |

-0.54 |

-0.72 |

22 |

| Hotan-5 |

1.81 |

-0.65 |

0.84 |

1.06 |

7 |

Kashi-5 |

-1.49 |

1.1 |

-0.73 |

-0.74 |

23 |

| Hotan-4 |

1.7 |

0.07 |

-0.24 |

0.99 |

8 |

Aksu-6 |

-1.54 |

0.45 |

-0.49 |

-0.89 |

24 |

| Kashi-1 |

1.36 |

-0.2 |

0.28 |

0.81 |

9 |

Aksu-5 |

-1.59 |

-0.07 |

-0.39 |

-1.03 |

25 |

| Bazhou-1 |

1.44 |

-0.18 |

-0.33 |

0.76 |

10 |

Aksu-4 |

-1.37 |

-2 |

0.85 |

-1.16 |

26 |

| Kashi-2 |

-0.45 |

2.9 |

-0.3 |

0.38 |

11 |

Aksu-7 |

-1.7 |

-1.47 |

1.07 |

-1.2 |

27 |

| Bazhou-6 |

-0.06 |

1.28 |

0.46 |

0.34 |

12 |

Kashi-8 |

-1.94 |

-0.27 |

0.17 |

-1.2 |

28 |

| Aksu-1 |

-0.11 |

1.12 |

0.32 |

0.26 |

13 |

Kashi-9 |

-1.52 |

-1.56 |

-1.63 |

-1.55 |

29 |

| Hotan-6 |

0.55 |

0.54 |

-1.28 |

0.25 |

14 |

Kashi-7 |

-3.22 |

-0.9 |

0.92 |

-1.99 |

30 |

| Hotan-3 |

0.91 |

-1.55 |

-1.35 |

-0.05 |

15 |

Aksu-3 |

-3.42 |

-0.72 |

0.37 |

-2.15 |

31 |

| Kashi-3 |

1.29 |

-1.57 |

-2.85 |

-0.07 |

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).