1. Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide [

1,

2]. It refers to a group of diseases characterized by uncontrolled and abnormal cell division and growth due to gene mutations. These cells can form tumors that may be benign or malignant, with the potential to spread to other parts of the body [

3]. In 2020, 19.3 million new cases were recorded globally, with colorectal cancer (CRC) being the third most common cancer in both men and women, accounting for 10% of cancer incidence and 9.4% of cancer mortality [

4,

5]

CRC encompasses cancers located in the large intestine, from the cecum to the rectum. Despite advancements in treatment, which have improved survival rates, CRC patients often face significant psychological challenges [

6,

7]. In this sense, it is common for people with CRC to experience pain that can have a significant impact on their quality of life, as well as their mental health [

8,

9]. The prevalence rate of pain in people with CRC is estimated to be more than 70 %, depending on the stage of the disease [

10]. Pain may be related to the treatment or to the tumor itself and, in fact, it has been seen that after the diagnosis of CRC, 51% of those affected showed pain or fatigue symptoms [

11]. Chronic cancer-related pain affects daily activities, relationships, mood, sleep, and overall health, often more severely than the cancer itself [

12,

13]

Beyond the physical symptoms associated with cancer, psychological problems are also commonly observed [

14]. The stress associated with diagnosis, fear of death, treatment, and prognosis can lead to mental health issues such as anxiety and depression [

6,

7]. Clinically significant depressive and anxiety symptoms are prevalent among CRC population, with anxiety rates ranging from 1.0% to 47.2% of patients, and depression rates ranging from 1.6% to 57.0% [

15]. And, compared to physically healthy individuals, colorectal cancer patients exhibit a roughly 10% higher prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms [

16]. Anxiety is particularly prevalent while awaiting diagnostic results, and sustained anxiety can lead to depressive symptoms and increased suicide risk, especially in advanced disease stages where physical and mental health decline [

17,

18]

Suicide is a complex; multifactorial phenomenon often linked to mental health problems and poses a significant public health issue. Globally, more than 700,000 people die by suicide each year [

19]. Cancer has been identified as a factor associated with suicide risk among affected individuals, citing poor prognosis, disease progression, symptoms of depression, feelings of helplessness, disturbed interpersonal relationships and uncontrolled pain as contributing factors [

20]. People with cancer are at double the risk of dying by suicide compared to the general population [

21]. Specifically, regarding CRC, numerous studies based on national registries have underscored the risk of suicide within this population [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Despite the above, the perception of threat from the disease is crucial for adaptive responses, influencing emotional distress and coping mechanisms [

27]. The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation suggests that individuals create mental representations of their illness based on available information to manage their condition effectively [

28]. These representations are influenced by cultural and social factors, information from significant others, and personal experiences, shaping their perception of the disease and its threat [

27,

29]. A higher perception of threat is associated with an increased distress symptoms and risk of suicide, regardless of the actual threat level of the diagnosis [

27].

Person-centered care from a holistic perspective is crucial in reducing the risk of suicide among individuals with cancer [

30]. The role of nursing in cancer patients care is increasingly recognized, enhancing the likelihood of improving treatment and reducing anxiety [

31]. Recently, the role of the Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) has expanded as an advanced nursing practice [

32]. In the context of oncology care, it has been observed to significantly enhance cancer patient outcomes by providing psychological support, offering information, assisting in symptom management, and improving service delivery, thereby increasing overall satisfaction [

33]. Nurses fulfill a bridging role between the patient, family, and other healthcare professionals such as physicians; thus, the development of effective communication skills and multidisciplinary collaboration are essential key components [

34].

Given the global impact and increasing incidence of CRC and suicide, it is essential to understand the interplay between pain, threat perception, and emotional distress in this population to enhance person-centered cancer care through nursing practices. The objective of this study is to identify the predictors of suicide risk in individuals with CRC. It is expected: (H1) Higher levels of pain will be associated with an increased emotional distress and risk of suicide in individuals with CRC; (H2) Greater perception of illness threat will be associated with an increased emotional distress and risk of suicide in individuals with CRC; (H3) Higher levels of emotional distress will be associated with an increased risk of suicide in individuals with CRC; (H4) Combined, pain, threat perception, and emotional distress will significantly predict suicide risk in individuals with CRC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study included 71 individuals with GI cancer from the Oncology Unit of the Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia (CHGUV). Participants were aged between 27 and 88 years (M = 65.18, SD = 12.02), with 76.06% men and 23.94% women. Diagnoses included colon cancer (52.11%), rectal cancer (23.94%), and sigmoid cancer (23.94%). Regarding the cancer stage, 1.54% are in stage 0, 18.46% in stage 1, 44.62% in stage 2, 32.3% in stage 3, and 3.08% in a stage 4.

Inclusion criteria from the GRAMGEA protocol [

35] were: a) undergoing major abdominal surgery not suitable for ambulatory major surgery; b) aged between 18 and 85 years; c) adequate cognitive state (able to understand and collaborate); d) anesthesia risk ≤ II according to the ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) scale. Exclusion criteria were a) requiring urgent surgery or b) being a pediatric patient.

Additional inclusion criteria were a) having completed the entire battery of questionnaires; b) being informed about the study procedure and having signed the informed consent; c) being diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancer.

2.2. Variables and Instruments

Sociodemographic and clinical variables (marital status, living situation, children, occupation, diagnosis, stage, hospitalization) were assessed using a custom scale. In addition, the following variables were assessed with questionnaires validated for the study sample:

Pain: evaluated using the Bodily Pain subscale of the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) [36]. The SF-36 measures various aspects of health-related quality of life, including pain intensity and its limitations. The Bodily Pain subscale is scored from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate less pain and fewer limitations due to pain. The Cronbach's alpha for the SF-36 ranges from 0.71 to 0.94 across subscales [37]. In a review with a Spanish population, including cancer patients, the scales exceeded the proposed reliability standard (α ≥ 0.70) [38]. In this study, the observed internal consistency of the bodily pain subescale was α = .87.

Perception of Threat: Measured using the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ) [

39,

40]. This questionnaire comprises 9 items that evaluate cognitive and emotional perceptions of illness threat. The first 8 items correspond to factors such as consequences, duration, personal control, treatment control, identity, concern, emotional response, and understanding. These are rated on a Likert scale from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating a greater perception of threat. The final item is an open question about the perceived main causes of the illness. Overall scores are calculated by reversing items 3, 4, and 7, and summing them with items 1, 2, 5, 6, and 8. Higher total scores indicate a greater perceived threat of illness [

41,

42]. The B-IPQ has shown adequate psychometric properties, with internal consistency indices ranging from α = 0.67 to 0.98 [

42,

43,

44,

45]. In this study, Cronbach's alpha was α = .67.

Emotional Distress: Assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[

46]. This scale measures anxiety and depression symptoms without considering somatic symptoms, making it suitable for individuals with medical diagnoses. The HADS comprises 14 items forming two subscales: anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D). Each item is rated on a Likert scale from 0 (minimum) to 3 (maximum presence of symptoms). Items 1, 3, 6, 8, 10, 11, and 13 are reversed. Total scores for each subscale indicate levels of anxiety and depression. Additionally, a total Emotional Distress score can be obtained by summing both subscales. The interpretation of HADS scores is as follows: 0-7 indicates normal anxiety and depression symptoms, 8-10 probable case of anxiety or depression, and >10 clinical problem. Regarding emotional distress ≥ 20 scores indicated a clinical problem [

47]. For this study, Cronbach’s alpha was α = .90.

Suicide Risk: Assessed using the Plutchik Suicide Risk Scale [

48,

49]. This instrument measures the level of suicide risk and feelings related to depression and hopelessness. It consists of 15 dichotomous items (yes/no), with one point awarded for each affirmative answer, resulting in a maximum score of 15. Higher scores indicate a higher risk of suicide, with scores of six or more indicating significant risk [

50]. The Spanish version demonstrated adequate psychometric properties, with an internal consistency of α = 0.90 [

49,

51]. In this study, Cronbach's alpha was α = 0.71.

2.3. Procedure

Participants were informed about the study and completed the consent form before the administration of the questionnaire battery. Assessments were conducted in the Health Psychology Unit of CHGUV between 2019 and 2024. Participants were referred by the General and Digestive Surgery Service under the GRAMGEA protocol (Grupo de Rehabilitación Multimodal del hospital General). GRAMGEA is a multidisciplinary team that includes personnel from surgery, anesthesiology, endocrinology-nutrition, rehabilitation, psychology, nursing, auxiliary services, and administrative staff. The main objective of GRAMGEA is to ensure that patients are in optimal functional and nutritional condition for surgery.

2.4. Design

The study used a non-experimental, cross-sectional design, collecting data at a single time point for exploratory and descriptive purposes.

2.5. Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 28.0. Descriptive analyses described the sample based on sociodemographic and clinical variables. Pearson correlations were conducted to examine relationships between suicide risk, pain, threat perception, and emotional distress. We conducted linear regressions to predict suicide risk in people with CRC cancer through perceived threat of illness, pain and emotional distress.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

According to the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample, the majority (50.09 %) were married, 24.24 % were widowed, 15.15 % were divorced and 1.52 % were single. Of the total sample, 15.38% live alone and the remaining 84.62% lived with someone, and 78.33 % had children. Regarding employment status, the majority were retired (50.77 %), a smaller percentage were on temporary leave (12,31 %) and the rest were employed (9.23 %), dedicated to housework duties (9.23 %), unemployed (7.69 %) or on permanent disability (4.62 %). According to their diagnosis, 52.11 % of the sample suffered from colon cancer, 23.94 % rectal cancer and the other 23 .94 % sigmoid cancer. Regarding the cancer stage, the majority were in stage 2 (44.62 %) or 3 (32.30 %), a smaller percentage in satge 1 (18.4 %) and the remaining participants in stage 4 (3.08 %) or 0 (1.54 %). Of the total sample, 20.75% had been hospitalized, while the remainder had not (

Table 1).

In relation to pain, moderate to high levels were observed (M = 31.56, SD = 33.51), considering that lower scores indicate greater pain and more limitations. 63.60 % of the sample demonstrated impairment with an impact below 50%.

About threat perception, most of the obtained values were low to moderate (M = 33.30; SD = 13.28). It was observed that the following factors were particularly relevant: low personal control over the disease, as well as low understanding, the associated concerns, and emotional impact. Conversely, participants reported perceiving an improvement in the disease due to treatment.

| B-IPQ Factors |

M |

SD |

| Consequences |

4.51 |

3.27 |

| Timeline |

4.17 |

2.48 |

| Personal control |

6.49 |

3.50 |

| Treatment control |

1.71 |

1.98 |

| Indentity |

3.35 |

3.38 |

| Concern |

5.71 |

3.17 |

| Understanding |

2.30 |

2.84 |

| Emotional response |

4.84 |

3.30 |

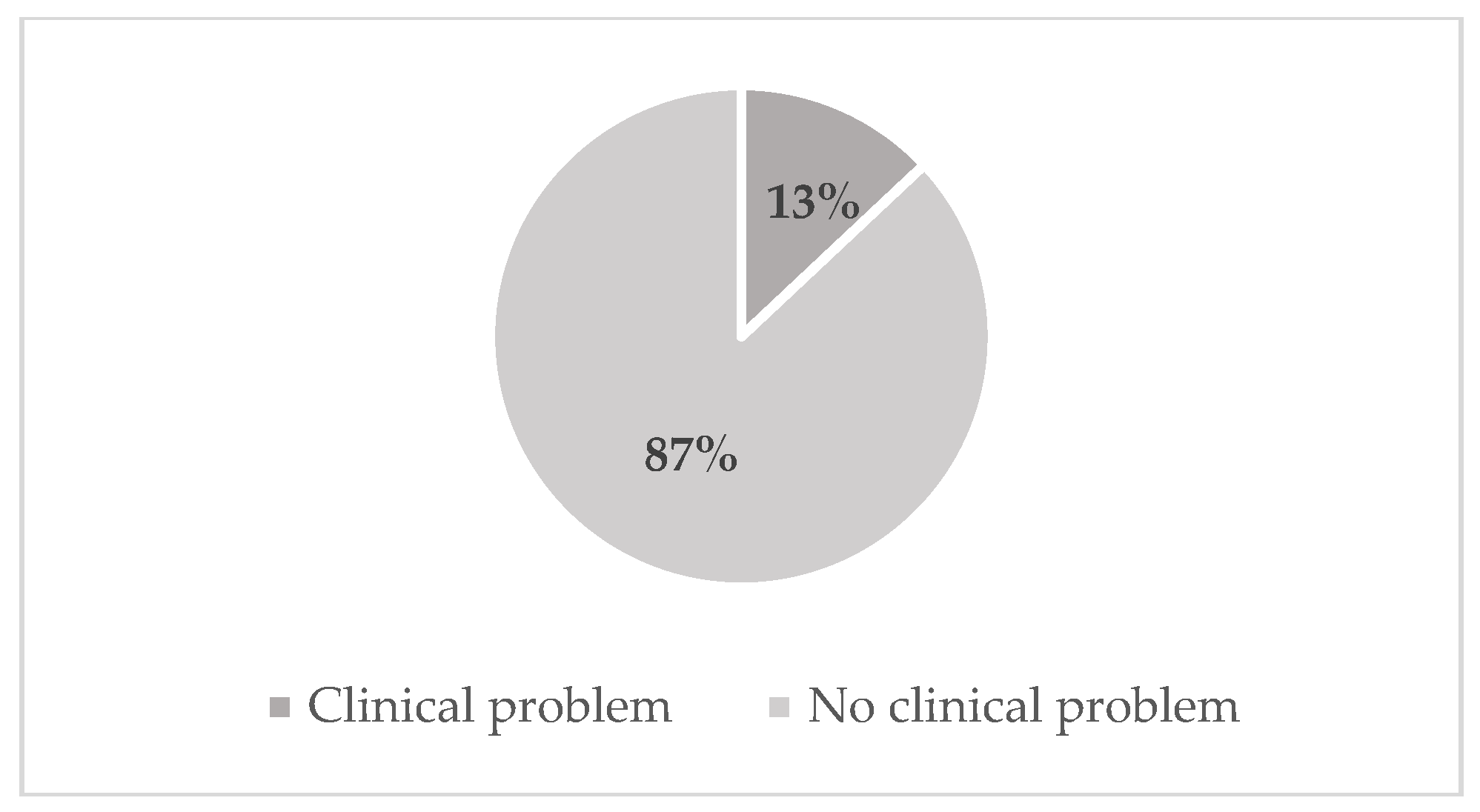

Regarding emotional distress, moderate levels were observed within the participants (M = 10.77;

SD = 7.37). 13.04 % of the sample showed clinically significant emotional distress (

Figure 1).

In terms of suicide risk, participants generally showed low scores (M = 2.63; SD = 2.45). However, 16.50 % exhibited a total score above 6, indicating a high suicide risk (Figure 3).

3.2. Correlational Analysis

Pearson correlations were conducted to examine relationships between suicide risk, pain, threat perception and emotional distress. Significant and positive correlations were found between suicide risk and all variables evaluated: pain (rx = .51; p ≤ .01), threat perception (rx = .45; p ≤ .01), and emotional distress (rx = .60; p ≤ .01). Positive significant correlations were also shown between pain and threat perception (rx = .46; p ≤ .01), pain and emotional distress (rx = .40; p ≤ .01), and threat perception and emotional distress (rx = .49; p ≤ .01).

Table 3.

Correlations between pain, threat perception, emotional distress and suicide risk.

Table 3.

Correlations between pain, threat perception, emotional distress and suicide risk.

| |

Pain |

Threat perception |

Emotional distress |

Suicide risk |

| Pain |

1 |

|

|

|

| Threat perception |

.46** |

1 |

|

|

| Emotional distress |

.40** |

.49** |

1 |

|

| Suicide risk |

.51** |

.45** |

.60** |

1 |

3.3. Predictive Analysis

A stepwise linear regression was conducted to predict suicide risk based on pain, illness threat perception, and emotional distress. The analysis was performed in two steps.

In the first step, pain and illness threat perception were entered as predictors. The results showed that these two variables together accounted for 28.80 % of the variance in suicide risk, the inclusion of these variables was significant (p < .001). In the second step, emotional distress was added as a predictor. This addition improved the model significantly, explaining 39.40 % of the variance in suicide risk. This final model was also significant (p < .001). These results suggest that pain, illness threat perception, and emotional distress are significant predictors of suicide risk in individuals with CRC, highlighting the importance of comprehensive emotional and psychological support for this population.

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression model.

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression model.

| |

|

|

|

Suicide risk in CRC |

|

| Predictors |

∆R2

|

∆F |

β |

t |

| |

Step 1 |

.31***

|

12.73***

|

|

|

| |

Pain |

|

|

.30 |

2.61*

|

| Illness threat perception |

|

|

.27 |

2.30*

|

| |

Step 2 |

.11***

|

10.77**

|

|

|

| |

Emotional distress |

|

|

.34 |

3.28**

|

| |

Durbin-Watson |

2.46 |

|

|

|

| |

R2ajd

|

.39***

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to identify the predictors of suicide risk in individuals with CRC, focusing on the roles of pain, illness threat perception, and emotional distress. The findings largely align with our hypotheses, highlighting the significant impact of these factors on suicide risk among CRC patients. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, the results indicate that higher levels of pain are significantly associated with increased emotional distress and, consequently, an elevated risk of suicide. This finding underscores the debilitating effect of pain on the psychological well-being of cancer patients. Chronic pain, can severely impair daily functioning and quality of life, contributing to feelings of hopelessness and despair that heighten suicide risk. These results support previous research emphasizing the need for effective pain management as a critical component of comprehensive cancer care [

8,

9]

Supporting Hypothesis 2, the study found that a greater perception of illness threat is associated with increased emotional distress and a higher risk of suicide. The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation suggests that individuals' mental representations of their illness, shaped by personal experiences and social influences, significantly impact their emotional responses [

28,

29]. In the context of CRC, people who perceive their illness as highly threatening are more likely to experience severe emotional distress, which can exacerbate suicidal ideation and behaviors. This finding highlights the importance of addressing patients' perceptions and fears through targeted psychological interventions. Interventions that aim to reshape illness perceptions and provide coping strategies can help reduce emotional distress and suicide risk in these patients.

Hypothesis 3 posited that higher levels of emotional distress would be directly associated with an increased risk of suicide. The results confirmed this hypothesis, indicating that emotional distress is a significant predictor of suicide risk in CRC patients. This aligns with existing literature that identifies anxiety and depression as prevalent issues among cancer patients, particularly those with a poor prognosis or advanced disease stages [

6,

52]. The strong association between emotional distress and suicide risk underscores the necessity for routine psychological screening and support for CRC patients throughout their treatment journey. Implementing regular mental health assessments and providing access to mental health professionals should be a standard part of oncological care.

As anticipated in Hypothesis 4, the combined model of pain, illness threat perception, and emotional distress significantly predicted suicide risk in individuals with CRC. Notably, emotional distress emerged as the strongest predictor within the model, indicating its central role in mediating the effects of pain and threat perception on suicide risk. These findings suggest that while pain and threat perception are critical factors, their impact on suicide risk is largely mediated through emotional distress. This integrated understanding calls for a holistic approach to patient care that simultaneously addresses physical symptoms, cognitive perceptions, and emotional well-being.

Despite the valuable insights gained, this study has several limitations. In the first place, the study had a cross-sectional design, which limited the possibility of establising causal relationships. Therefore, future longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the predictive relationships and explore potential mediators and moderators. Additionally, the sample size was relatively small, and all participants belonged to the same hospital center (monocentric study), which may not be representative of the broader CRC population. Nevertheless, we acknowledge the complexity of accessing individuals with CRC in hospital settings. Hence, further research with larger, multicenter and diverse samples, employing probabilistic sampling is warranted to enhance the generalizability of the findings.

In conclusion, this study underscores the critical role of pain, illness threat perception, and emotional distress in predicting suicide risk among CRC patients. Addressing these factors through integrated, multidisciplinary care approaches is essential to improve the mental health and overall well-being of individuals battling colorectal cancer. Within this framework nurses play a central role in person-centered care. On one hand, they are directly engaged with individuals suffering from cancer, providing essential emotional support and delivering necessary care and information. And on the other hand, they act as intermediaries between cancer patients and other healthcare practitioners, such as physicians and psychologists, thereby fostering collaboration and facilitating multidisciplinary teamwork.

The findings of this study have important clinical implications. First, they highlight the necessity of comprehensive pain management strategies to alleviate physical suffering and reduce associated emotional distress. Second, they emphasize the importance of psychological interventions aimed at modifying illness perceptions and providing emotional support. Counseling, third-generation therapies, as well as cognitive-behavioral therapy, could help individuals with CRC manage the situations they face due to the illness, adjust their expectations and perceptions, and emotionally process the situation. Lastly, the results advocate for regular psychological assessments to identify patients at high risk of suicide and implement timely interventions. Due to the significant role nurses play in the care of individuals with cancer, it is advisable to consider these recommendations. Management of pain, perception of threat, and emotional distress can be alleviated through a multidisciplinary and person-centered nursing approach, with particular emphasis on clinical symptom management, information provision, and emotional support. Therefore, future research focusing on nursing practices aimed at enhancing high-quality care is recommended, in order to assess their impact on the quality of life and well-being of individuals with cancer.

5. Conclusions

Our findings indicate that higher levels of pain and greater perception of illness threat are associated with increased emotional distress, which in turn significantly elevates the risk of suicide in this population. Importantly, emotional distress emerged as the strongest predictor of suicide risk, underscoring the need for comprehensive psychological support alongside effective pain management and interventions targeting illness perceptions.

The integration of physical, cognitive, and emotional aspects into patient care is essential for mitigating suicide risk among individuals with CRC. Health professionals, such as nurses, should prioritize routine psychological assessments and adopt multidisciplinary approaches that address both physical symptoms and psychological well-being. By addressing these multifaceted factors, we can enhance the quality of life and mental health outcomes for individuals with CRC, ultimately reducing the incidence of suicide in this vulnerable population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C.-Á. and L.L.-T.; methodology, E.C.-Á. and L.L.-T.; software, L.L.-T.; validation, L.L.-T., A.E., and M.P.-V.; formal analysis, L.L.-T., A.E., and M.P.-V; investigation, E.C.-Á. and L.L.-T.; resources, E.C.-Á.; data curation, L.L.-T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.-T., A.E.-A. and M.P.-V.; writing—review and editing, L.L.-T.; visualization, L.L.-T.; supervision, E.C.-Á.; project administration, E.C.-Á. and L.L.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Alba Espuig is a beneficiary of the Aid for Collaboration in Research from the University of Valencia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the study can be made available upon reasoned request to the corresponding author.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research beyond the role of study participants who completed the surveys.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted against the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for observational research [Von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLOS Medicine, 4(10), e296].

Use of Artificial Intelligence

In the present work, artificial intelligence has been used to revise and refine the English of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the manuscript would like to thank all the participants in the study for their collaboration. Their altruistic participation can help healthcare systems prevent emotional distress and decrease suicide rates in people with colorectal cancer.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Organización Mundial de La Salud (OMS). Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Tambo-Lizalde, E.; Aréjula-Tarongi, C.; Ramos-Jiménez, N. Prevención Del Cáncer y Factores de Riesgo. Available online: https://revistasanitariadeinvestigacion.com/prevencion-del-cancer-y-factores-de-riesgo/ (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- National Cancer Institute (NCI). Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/espanol/cancer/naturaleza/que-es (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Xu, P. Global Colorectal Cancer Burden in 2020 and Projections to 2040. Transl Oncol 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero Alcedo, J.M.; Prepo Serrano, A.R.; Loyo Álvarez, J.G. Autotrascendencia, Ansiedad y Depresión En Pacientes Con Cáncer En Tratamiento. Revista Habanera de Ciencias Médicas 2016, 15, 297–309. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Silva, M.A.; Ruíz Martínez, A.O.; González Escobar, S.; González-Celis Rangel, A.L.M. Ansiedad, Depresión y Estrés Asociados a La Calidad de Vida de Mujeres Con Cáncer de Mama. Acta Investig Psicol 2020, 10, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, S.; Bannister, K.; Dickenson, A.H. Cancer Pain Physiology. Br J Pain 2014, 8, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.I.; Kaasa, S.; Barke, A.; Korwisi, B.; Rief, W.; Treede, R.D. The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for ICD-11: Chronic Cancer-Related Pain. Pain 2019, 160, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, A.; Włodarczyk, M.; Makaro, A.; Sałaga, M.; Fichna, J. Management of Pain in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2021, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, A.M.; Weeks, J.C.; Kahn, K.L.; Tisnado, D.; Keating, N.L.; Dy, S.M.; Arora, N.K.; Mack, J.W.; Pantoja, P.M.; Malin, J.L. Symptom Prevalence in Lung and Colorectal Cancer Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015, 49, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.R.D.; Ramirez, J.D.; Farquhar-Smith, P. Pain in Cancer Survivors. Br J Pain 2014, 8, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paice, J.A.; Portenoy, R.; Lacchetti, C.; Campbell, T.; Cheville, A.; Citron, M.; Constine, L.S.; Cooper, A.; Glare, P.; Keefe, F.; et al. Management of Chronic Pain in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2016, 34, 3325–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.; Oveisi, N.; McTaggart-Cowan, H.; Loree, J.M.; Murphy, R.A.; De Vera, M.A. Colorectal Cancer and Onset of Anxiety and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr Oncol 2022, 29, 8751–8766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.N.; Huang, M.L.; Kao, C.H. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mols, F.; Schoormans, D.; de Hingh, I.; Oerlemans, S.; Husson, O. Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression among Colorectal Cancer Survivors from the Population-Based, Longitudinal PROFILES Registry: Prevalence, Predictors, and Impact on Quality of Life. Cancer 2018, 124, 2621–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloch, A.; Sandín, B.; Ramos, F. Manual de Psicopatología, Volumen II.; McGraw Hill: Madrid, España, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal García, P.; Muñoz Algar, M.J. Tratamiento Farmacológico de La Depresión En Cáncer. Psicooncologia (Pozuelo de Alarcon) 2016, 13, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates; Geneva, 2021.

- Amiri, S.; Behnezhad, S. Cancer Diagnosis and Suicide Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Archives of Suicide Research 2020, 24, S94–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Hofmann, L.; Baurecht, H.; Kreuzer, P.M.; Knüttel, H.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Seliger, C. Suicide Risk and Mortality among Patients with Cancer. Nat Med 2022, 28, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innos, K.; Rahu, K.; Rahu, M.; Baburin, A. Suicides among Cancer Patients in Estonia: A Population-Based Study. Eur J Cancer 2003, 39, 2223–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkenstam, C.; Edberg, A.; Ayoubi, S.; Rosén, M. Are Cancer Patients at Higher Suicide Risk than the General Population? A Nationwide Register Study in Sweden from 1965 to 1999. Scand J Public Health 2005, 33, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Mittleman, M.A.; Sparén, P.; Ye, W.; Adami, H.-O.; Valdimarsdóttir, U. Suicide and Cardiovascular Death after a Cancer Diagnosis. N Engl J Med 2012, 366, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Shi, H.Y.; Yu, H.R.; Liu, X.M.; Jin, X.H.; Yan-Qian; Fu, X. L.; Song, Y.P.; Cai, J.Y.; Chen, H.L. Incidence of Suicide Death in Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Affect Disord 2020, 276, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, C.; de la Croix, H.; Grönkvist, R.; Park, J.; Rosenberg, J.; Tasselius, V.; Angenete, E.; Haglind, E. Suicide after Colorectal Cancer—a National Population-Based Study. Colorectal Disease 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacomba-Trejo, L. Factores Psicosociales y de Adaptación En Adolescentes Con Enfermedad Crónica y Sus Familias, Universitat de València: Valencia, 2022.

- Cameron, L.; Leventhal, E.A.; Leventhal, H. Symptom Representations and Affect as Determinants of Care Seeking in a Community-Dwelling, Adult Sample Population. Health Psychology 1993, 12, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach, M.A.; Leventhal, H. The Common-Sense Model of Illness Representation: Theoretical and Practical Considerations. J Soc Distress Homeless 1996, 5, 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage-Bouchard, E.A.; Pailler, M.; Devine, K.A.; Flores, T. Optimizing Patient-Centered Psychosocial Care to Reduce Suicide Risk and Enhance Survivorship Outcomes Among Cancer Patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021, 113, 1129–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet Oncology The Importance of Nurses in Cancer Care. Lancet Oncol 2015, 16, 737. [CrossRef]

- East, L.; Knowles, K.; Pettman, M.; Fisher, L. Advanced Level Nursing in England: Organisational Challenges and Opportunities. J Nurs Manag 2015, 23, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, H.; Donovan, M.; McSorley, O. Evaluation of the Role of the Clinical Nurse Specialist in Cancer Care: An Integrative Literature Review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2021, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.M.; Charalambous, A.; Owen, R.I.; Njodzeka, B.; Oldenmenger, W.H.; Alqudimat, M.R.; So, W.K.W. Essential Oncology Nursing Care along the Cancer Continuum. Lancet Oncol 2020, 21, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañ Navarro, I.; Castañ Navarro, A.M. Análisis de La Aplicación de Gramgea En La Práctica Diaria y Su Evolución En Los 2017 al 2022. Ocronos 2023, 6, 318. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual Framework and Item Selection. Med Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, J.; Prieto, L.; Jm, A. La Versión Española Del SF-36 Health Survey (Cuestionario de Salud SF-36): Un Instrumento Para La Medida de Los Resultados Clínicos. Med Clin 1995, 104, 771–776. [Google Scholar]

- Vilagut, G.; Ferrer, M.; Rajmil, L.; Rebollo, P.; Permanyer-Miralda, G.; Quintana, J.M.; Santed, R.; Valderas, J.M.; Ribera, A.; Domingo-Salvany, A.; et al. El Cuestionario de Salud SF-36 Español: Una Década de Experiencia y Nuevos Desarrollos. Gac Sanit 2005, 19, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinman, J.; Petrie, K.J.; Moss-Morris, R.; Horne, R. The Illness Perception Questionnaire: A New Method for Assessing the Cognitive Representation of Illness. Psychol Health 1996, 11, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Huergo, V.; Viladrich, C.; Pujol-Ribera, E.; Cabezas-Peña, C.; Núñez, M.; Roura-Olmeda, P.; Amado-Guirado, E.; Núñez, E.; Del Val, J.L. Percepción En Enfermedades Crónicas: Validación Lingüística Del Illness Perception Questionnaire Revised y Del Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire Para La Población Española. Aten Primaria 2012, 44, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacomba-Trejo, L.; Mateu-Mollà, J.; Álvarez, E.C.; Benavent, A.M.O.; Serrano, A.G. Threat Perception of Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Its Association with Anxious and Depressive Symptomatology. Revista de Psicologia de la Salud 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Moreno, S.; Lacomba-Trejo, L.; Casaña-Granell, S.; Prado-Gascó, V.J.; Montoya-Castilla, I.; Pérez-Marín, M. Psychometric Properties of the Questionnaire on Threat Perception of Chronic Illnesses in Pediatric Patients. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Fielding, R.; Soong, I.; Chan, K.K.K.; Lee, C.; Ng, A.; Sze, W.K.; Tsang, J.; Lee, V.; Lam, W.W.T. Psychometric Assessment of the Chinese Version of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire in Breast Cancer Survivors. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, B.H.; Vos, R.C.; Heijmans, M.; Shariff-Ghazali, S.; Fernandez, A.; Rutten, G.E.H.M. Validity and Reliability of a Malay Version of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leysen, M.; Nijs, J.; Meeus, M.; Paul van Wilgen, C.; Struyf, F.; Vermandel, A.; Kuppens, K.; Roussel, N.A. Clinimetric Properties of Illness Perception Questionnaire Revised (IPQ-R) and Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (Brief IPQ) in Patients with Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review. Man Ther 2015, 20, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta psychiatr. scand 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacomba-Trejo, L.; Casaña-Granell, S.; Pérez-Marín, M.; Montoya-Castilla, I. Estrés, Ansiedad y Depresión En Cuidadores Principales de Pacientes Con Diabetes Mellitus Tipo 1. Calidad de vida y salud 2017, 10, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Plutchik, R.; van Praag, H.M.; Conte, H.R.; Picard, S. Correlates of Suicide and Violence Risk 1: The Suicide Risk Measure. Compr Psychiatry 1989, 30, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, G.; Montero, J.; Jáuregui, J.; Villanueva, R.; Casado, M.A.; Marin, J.J.; Santo-Domingo, J. Validación de La Escala de Riesgo Suicida de Plutchik En Población Española. Arch Neurobiol (Madr) 1998, 61, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lacomba-Trejo, L.; Valero-Moreno, S.; Mateu-Mollá, J.; Sanz-Cruces, J.M.; García-Cuena, I. Relación Entre Riesgo Suicida, Síntomas Depresivos y Limitaciones Sociales En El Trastorno Adaptativo. Revista de Investigación en Psicología Social 2016, 4, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Tabares, A.S.; Núñez, C.; Caballo, V.E.; Paula Agudelo Osorio, M.P.; Grisales Aguirre, A.M. Predictores Psicológicos Del Riesgo Suicida En Estudiantes Universitarios. Behavioral Psychology / Psicología Conductual 2019, 27, 391–413. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ma, C. Anxiety and Depression during 3-Year Follow-up Period in Postoperative Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients: Prevalence, Vertical Change, Risk Factors, and Prognostic Value. Ir J Med Sci 2023, 192, 2621–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).