1. Introduction

Ranking as the fourth most crucial nutrient for plants, sulfur plays a pivotal role in their nutrition. The existence of sulfur, which ranges from 0.2% to 0.5% of the dry mass depending on the species, is crucial for several biological processes such as photosynthesis, respiration, and the formation of cell membranes [

1]. Prosthetic groups such as Fe-S centers, glutathione, glucosinolates, and chloroplasts, as well as coenzymes like biotin, thiamine pyrophosphate, coenzyme A, and

S-adenosylmethionine, all possess sulfur [

2]. Furthermore, sulfur significantly contributes to heavy metal detoxification through phytochelatins and glutathione, thereby enhancing plant stress resistance and ultimately impacting crop yields and quality [

2,

3,

4]. A lack of sulfur can considerably impact crop growth, development, disease resistance, and nutritional quality due to its involvement in various biochemical processes [

5].

Although leaves possess the ability to absorb sulfur dioxide (SO

2) and hydrogen sulfide (H

2S), plants predominantly obtain sulfur from inorganic sulfate present in the soil [

2]. Upon absorption, ATP sulfurylase activates sulfate to produce adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (APS), which can undergo phosphorylation to 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) via a secondary pathway. PAPS then serves as a sulfate group donor for synthesizing specialized metabolites [

3,

5,

6]. Plants transform sulfate into L-cysteine and other compounds through the sulfur assimilation pathway. The initial step in the process is the conversion of adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (APS) to sulfite and adenosine monophosphate (AMP) by adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate reductase. This is followed by the conversion of sulfite to sulfide by sulfite reductase, which occurs exclusively within plastids [

2]. In contrast to sulfate reduction, L-cysteine production can occur in the cytoplasm, mitochondria, and plastids.

O-Acetylserine(thiol) lyase (OAS-TL, EC 4.2.99.8) forms the first sulfur-containing organic molecule by combining sulfide with

O-acetylserine (OAS) [

7]. A pyridoxal 5′-phosphate cofactor is present in the two identical subunits forming the homodimeric enzyme OAS-TL. During L-cysteine production, sulfide replaces the acetoxy group of OAS [

7]. In this process, serine

O-acetyltransferase (SAT) produces OAS by transferring the acetate group from acetyl-CoA to L-serine [

8].

Weeds are the foremost challenge in modern agriculture, threatening crop growth and productivity. With 23 distinct modes of action, synthetic herbicides have been devised to counteract weed growth. However, their overuse has resulted in environmental damage, human health hazards, and the emergence of herbicide-resistant weed species. There are 272 resistant weed species and over 500 reported cases (species × site of action) worldwide [

9]. Our research team focuses on identifying and evaluating new herbicides with innovative modes of action. We employ

in silico,

in vitro, and in vivo approaches to gauge the effectiveness of enzyme inhibitors with herbicidal potential.

Specific OAS-TL inhibitors, such as alanine β-substituted compounds and anionic inhibitors, can disrupt sulfur assimilation and act as selective herbicides. In vitro assays with OAS-TL from spinach (

Spinacea oleracea) demonstrated that these inhibitors bind to both the E and F forms of OAS-TL in a ping-pong kinetic model [

10]. Leveraging the crucial role of enzymes in plant sulfur metabolism and employing homology modeling and virtual screening of maize OAS-TL, we have identified

S-benzyl-L-cysteine (SBC) as an enzyme inhibitor. Our studies with three-day-old maize and

Ipomoea grandifolia seedlings exposed to SBC for 96 h revealed that SBC non-competitively inhibits OAS-TL, impairing L-cysteine production and inhibiting seedling growth. In addition, maize plants exposed to SBC for 14 days exhibited reduced growth due to diminished photosynthetic CO

2 assimilation [

11].

I. grandifolia (Dammer) O’Donell, a member of the Convolvulaceae family and a type of eudicot with C3 photosynthesis, is commonly found in tropical and subtropical regions. It poses a significant threat to the yield and quality of crops, especially soybean [

12]. As a weed,

I. grandifolia exhibits resistance to glyphosate, possibly due to limited herbicide mobility within the plant. Moreover, glyphosate has increased plant tolerance levels, suggesting a natural evolution of resistance [

13].

Since sulfur is an essential constituent of Fe-S centers, the cytochrome

b6f complex, ferredoxin, and redox metabolism [

14], it can significantly affect the photosynthetic capacity of plants. Thus, our current work has three-fold objectives. First, we assess the effect of SBC on the growth of

I. grandifolia plants. Secondly, we evaluate the effect of SBC on photosynthesis by monitoring gas exchange parameters and chlorophyll

a fluorescence. Finally, we measure the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), markers of lipid peroxidation (conjugated dienes and malondialdehyde), and the activities of antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase—SOD, catalase—CAT, and peroxidase—POD).

4. Discussion

Treatment with SBC resulted in a significant reduction in the growth of

I. grandifolia at all concentrations tested. Our previous study has shown that SBC inhibits OAS-TL, consequently disrupting the biosynthesis of L-cysteine and related sulfur-containing compounds [

28]. By hindering the biosynthesis of L-cysteine, the assimilation of sulfur is compromised. A lack of assimilated sulfur in plants can lead to severe damage, such as stunted growth and leaf chlorosis, particularly pronounced in young plants [

2]. This has been noted in rice [

29], maize, and

I. grandifolia [

28]. Compared to the control group,

I. grandifolia plants treated with 1.0 mM SBC showed reduced leaf, stem, and root lengths, and decreased fresh and dry mass. At higher concentrations (2.5 and 5.0 mM), the plants stopped growing. Additionally, internerval chlorosis was visible in the fully expanded first leaves.

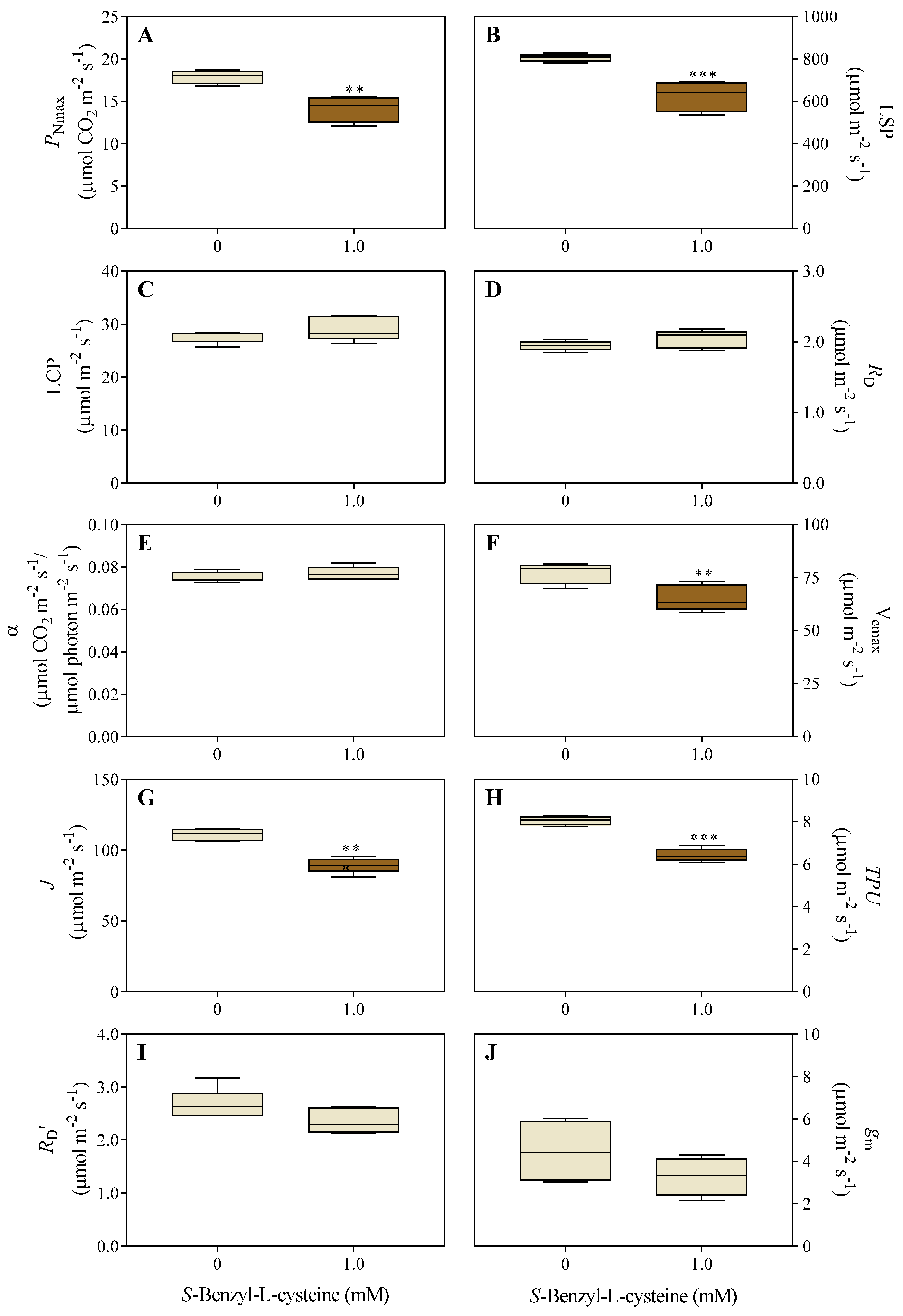

Measurements of gas exchange and chlorophyll

a fluorescence are valuable tools for understanding photosynthesis and stress responses [

30,

31]. In our study, 1.0 mM SBC decreased photosynthetic parameters (

PNmax, LSP, V

cmax,

J,

TPU,

gs, ϕ

PSII, ETR, q

P, F

m, and F

v) and increased ROS and oxidative stress markers (conjugated dienes and malondialdehyde) in

I. grandifolia. The lack of assimilated sulfur inhibits the biosynthesis of essential components in the photosynthetic electron transport chain and enzymes involved in carbon metabolism, thereby reducing photosynthesis and producing ROS [

2]. Our evaluation of

I. grandifolia plants further revealed a decrease in

PNmax and LSP, likely due to reductions in

gs and/or interference with CO

2 assimilation reactions. To achieve maximum photosynthetic capacity (

PNmax), it is essential to align biophysical processes that transport CO

2 through the leaves and stomata with biochemical processes occurring in the thylakoids, stroma, mitochondria, and cytoplasm of the cell [

18].

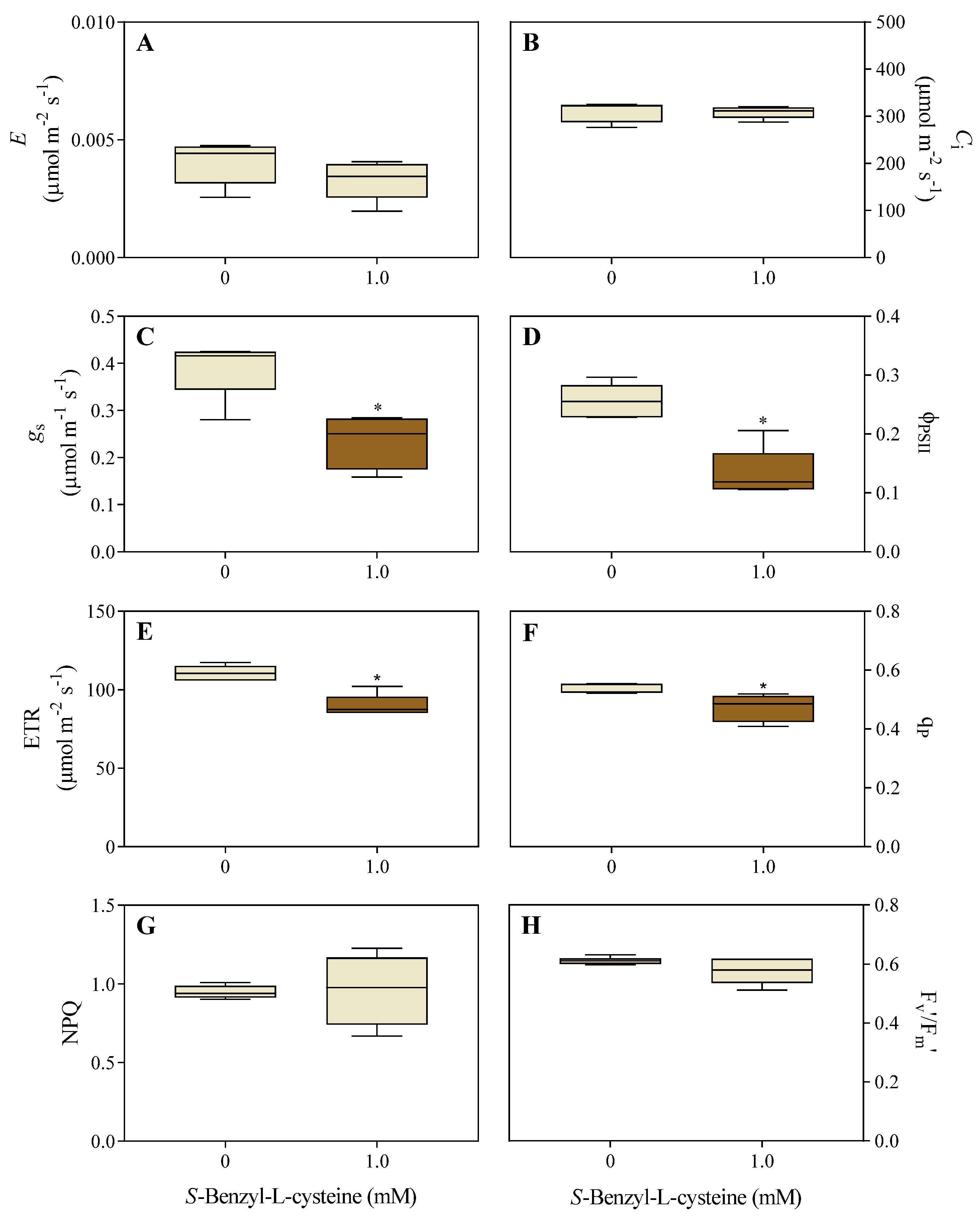

Analysis of punctual gas exchange measurements in

I. grandifolia plants revealed no significant alteration in

E and

Ci but a reduction in

gs. Soybean plants treated with benzoxazolinone [

32], allelochemical L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) or an aqueous extract of

Mucuna pruriens [

33] also showed decreases in

PNmax and

gs. Stomatal limitation of photosynthesis reduces

gs and

Ci [

34,

35]; the latter was not observed in our data. Despite the reduction in

gs,

Ci may remain unchanged due to a decrease in V

cmax, as explained later.

Beyond stomatal limitations, non-stomatal factors can also impede photosynthesis, including diminished activity of photosystem II (PSII) or inhibition of electron transport [

36]. Chlorophyll

a fluorescence is a non-invasive measure of ϕ

PSII activity, providing insights into the structure and function of the photosynthetic apparatus. These fluorescence parameters, which primarily reflect the photochemical phase of photosynthesis, precisely delineate the efficiency of PSII in capturing light energy and converting it into chemical energy [

20,

37]. Our data showed a significant decrease in ϕ

PSII, indicating a decline in the ability of chlorophyll to absorb light for photochemical reactions [

38]. Similar changes in PSII activity have been reported in sulfur-deprived plants [

29] and in soybean plants subjected to benzoxazolinone [

32], L-DOPA [

33], and

t-aconitic acid [

35].

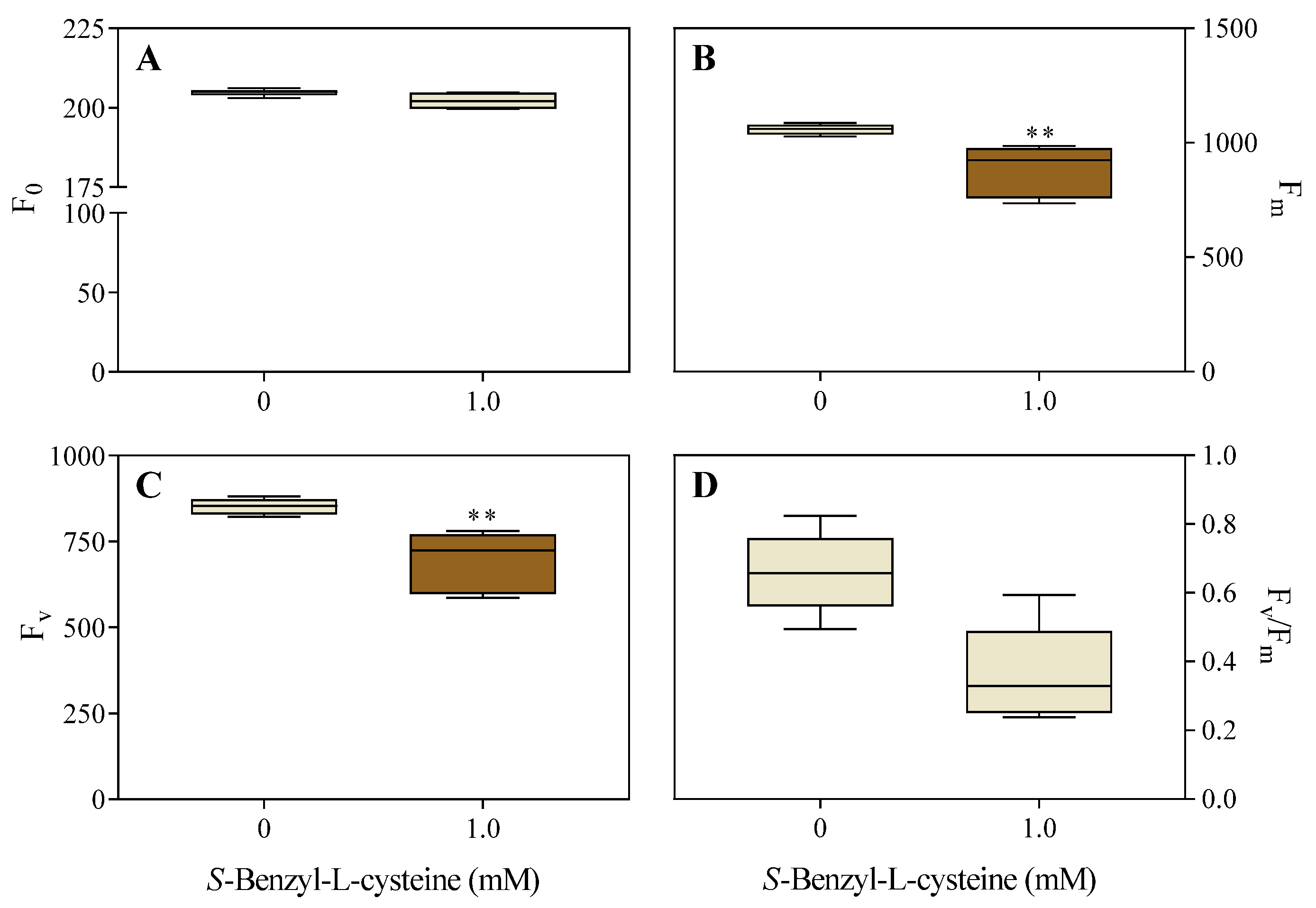

As demonstrated herein, the diminished efficiency of the PSII reaction center, as indicated by a decrease in ϕ

PSII, can significantly impact ETR. Given that ϕ

PSII can estimate the ETR, it provides valuable insights into both photosynthetic efficiency and carbon fixation [

38]. Furthermore, when analyzing ϕ

PSII, it is imperative to consider two key parameters: q

P and F

v’/F

m’ [

37]. The q

P value elucidates the proportion of open PSII reaction centers. In

I. grandifolia plants submitted to SBC, we observed a 12% decrease in q

P, signifying a higher proportion of closed reaction centers. This closure renders plants susceptible to photoinhibition due to reduced excitation energy utilized for photochemistry and an accumulation of the reduced Q

A fraction [

39]. Despite these alterations, F

v’/F

m’, which gauges the effective photochemical quantum efficiency under light, as well as NPQ and the PSII structural integrity parameter (F

v/F

m), remained unchanged in response to SBC exposure. However,

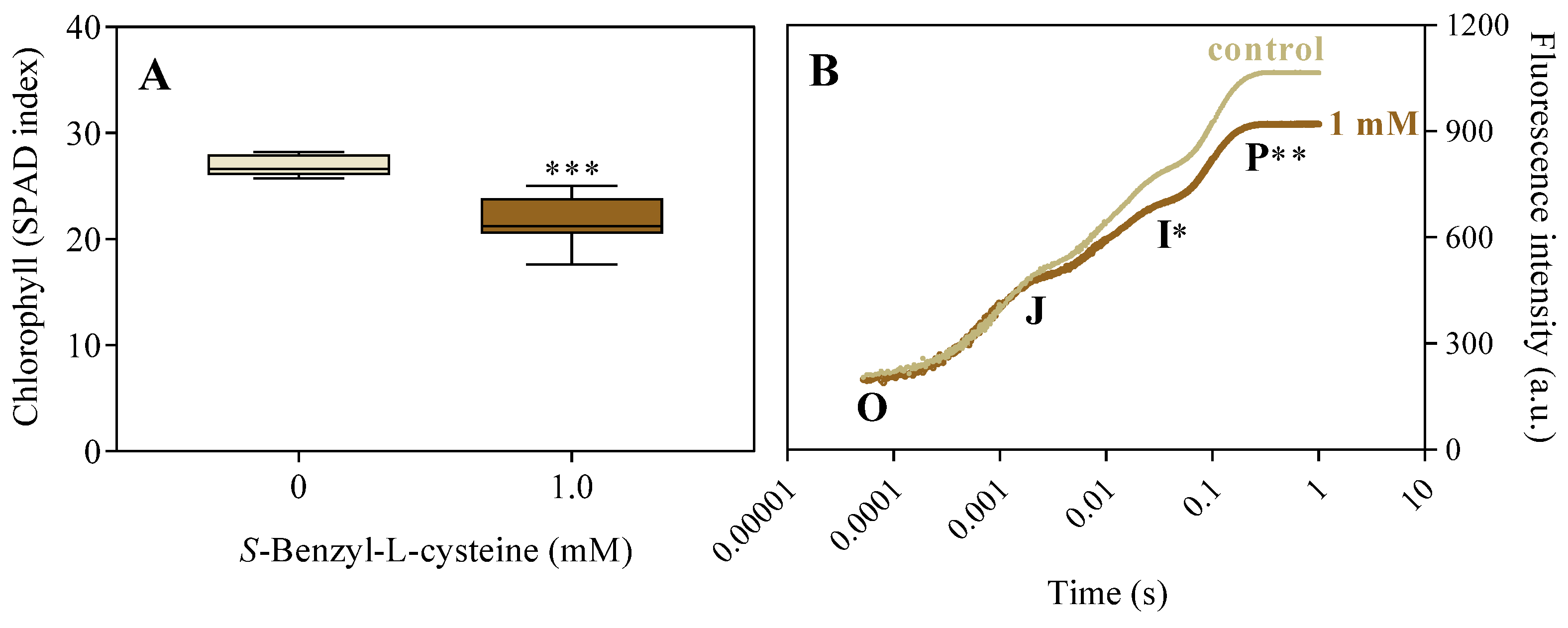

I. grandifolia plants submitted to SBC exhibited decreased chlorophyll levels, like those observed in sulfur-deficient rice plants [

29]. In a nutshell, this finding underscores the broader impact of SBC on the photosynthetic apparatus.

The OJIP curve provides a detailed analysis of chlorophyll

a fluorescence kinetics, describing the oxidation-reduction processes and electron transport dynamics from chlorophyll excitation to the reduction of final acceptors [

40]. Thus, the OJIP curve can be used to describe the photochemical quantum yield of PSII and the transport of electrons within the photosynthetic machinery [

20]. The OJIP curve comprises three distinct phases. The initial phase (O to J) involves the reduction of Q

A, the primary electron acceptor of the PSII, accompanied by an increase in fluorescence depending on the absorbed photons [

20]. Subsequently, the second phase (J to I) reveals a decline in the plastoquinone (PQ) pool, indicating a complete reduction of the secondary electron acceptor (Q

fr), followed by PQ

BH

2 reoxidation facilitated by the cytochrome

b6f complex. The final phase (I to P) involves the reduction of the final electron acceptors on the acceptor side of PSI, including NADP

+ and ferredoxin. In essence, the shape of the OJIP transients is a valuable indicator of the structural stability of PSII and provides insights into energy fluxes between its components. Herein, the OJIP curve revealed that exposure to SBC reduced the J to I and I to P phases in

I. grandifolia plants, indicating reduced PQ

BH

2 reoxidation and final acceptor reduction processes mediated by the cytochrome

b6f complex, PSI, and ferredoxin. When plants are treated with SBC, the inhibition of OAS-TL impairs the synthesis of L-cysteine, causing expected changes in related steps. This primary effect confers sulfur groups necessary for forming essential photosynthetic complexes. For instance, the cytochrome

b6f complex has a 2Fe-2S center and a Rieske protein, while PSI has three Fe-S centers (Fx, Fa, and Fb), and ferredoxin has a 4Fe-4S center. In simple terms, sulfur metabolism and photosynthesis are closely related, and changes in physiology induced by SBC may be explained by this interaction.

An alternative approach to understanding how C3 photosynthesis adapts to diverse conditions, such as SBC treatment, is the method developed by Farquhar et al. [

41]. This method categorizes photosynthesis into three distinct states: Rubisco-limited, 1.5-biphosphate ribulose (RuBP)-limited, and

TPU-limited. In the initial state, enzyme limitation is predominantly attributed to the low concentration of CO

2 rather than its V

max, assuming a saturating supply of RuBP. In the second state, photosynthesis is limited by the regeneration of RuBP. Under elevated CO

2 conditions, the rate at which Rubisco utilizes RuBP surpasses the regenerative capacity of other enzymes in the Calvin cycle. Finally, the

TPU-limited state occurs when the chloroplast reactions generate products more rapidly than the leaf’s capacity to utilize them, mainly but not exclusively phosphate triose [

42].

Steady-state photosynthetic CO

2 responses (

PN/

Ci curves) are valuable tools for accurately assessing the plant’s photosynthetic capacity, efficiency, and the upper limits of photosynthesis rates [

43]. Our thorough analysis has revealed that the application of 1.0 mM SBC resulted in a substantial decrease of V

cmax,

J, and

TPU, which represent the primary limitations of photosynthesis under conditions of light saturation [

44].

A decline in photosynthesis may occur from various factors, including decreased Rubisco activity due to stomatal closure, resulting in diminished CO

2 levels within the intercellular space [

45]. Alternatively, a decrease in Rubisco amounts, as observed in sulfur-free rice plants [

29], may decrease photosynthesis. This seems to be the case with SBC exposure.

A decreased

J value, for instance, reduces the availability of NADPH required for the regeneration reactions of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate. This is particularly relevant in the context of herbicides, many of which kill plants by obstructing electron transport. C-group herbicides such as diuron, atrazine, and metribuzin inhibit photosynthesis by binding to the D1 protein complex, disrupting electron transport from Q

A to Q

B, impeding CO

2 fixation, and inhibiting NADPH and ATP production [

9,

46].

The blockage in electron transport also hinders the activation of crucial enzymes (ribulose-5-phosphate-kinase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase) via the ferredoxin-thioredoxin system. Under light conditions, electrons from PSI reduce ferredoxin, which donates electrons to thioredoxin. In its reduced state, thioredoxin donates electrons to reduce the disulfide bonds of Calvin cycle enzymes, thereby activating them. Additionally, we observed a decrease in the

TPU value due to diminished

J values, compromised ferredoxin-thioredoxin system, and cycle enzyme function. The disulfide bonds between critical Cys residues in these enzymes are indispensable for their catalytic activities. According to the findings of Foletto-Felipe [

11], leaf proteome analysis revealed a reduction in Calvin cycle enzyme expression in maize plants exposed to SBC.

A blockage in electron transport inevitably activates chlorophyll into a high-energy state known as the triplet state. This state can generate harmful radicals in membrane unsaturated fatty acids or react with oxygen to produce singlet oxygen [

47,

48]. Elevated levels of ROS cause significant cell damage, degrading proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and DNA, ultimately culminating in cell death [

49]. Chloroplasts are the primary source of ROS within plant cells [

49]. We observed significant ROS levels concomitant with high MDA levels, a lipid peroxidation marker, and conjugated dienes in both leaves and roots.

To prevent oxidative damage caused by ROS, plants utilize a combination of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, POD, CAT, ascorbate peroxidase—APX, and glutathione reductase) and antioxidant compounds (glutathione, ascorbate, α-tocopherol, proline, and flavonoids) [

49]. We assessed the activities of SOD, POD, and CAT. SOD is the first line of defense against ROS by dismutating O

2•- to H

2O

2, while CAT and POD detoxify H

2O

2 into H

2O [

50]. Herein, we found that the activities of SOD, POD, and CAT remained unchanged in both the leaves and roots of

I. grandifolia. However, SBC increased ROS content and oxidative damage. This discrepancy could be attributed to decreased levels of L-cysteine and L-methionine, which may have prevented the activation and synthesis of antioxidant system enzymes due to the inhibitory effect of SBC on OAS-TL, potentially compromising protein structure.

Although SBC does not directly inhibit photosynthesis, it does impact electron transport efficiency and increases ROS and lipid peroxidation, akin to PSII-inhibiting herbicides [

9]. Depending on the dosage, C-group herbicides have elicited varied antioxidant enzyme responses. For example, in foxtail millet (

Setaria italica) plants treated with atrazine, a PSII-inhibiting herbicide, ROS and malondialdehyde levels increased. Conversely, the activities of POD and APX increased, while CAT and SOD activities decreased [

51]. Similarly, wheat plants exposed to prometryne, another PSII-inhibiting herbicide, exhibited elevated malondialdehyde content, indicating oxidative damage [52]. Furthermore, at low doses of this herbicide, the activities of SOD, POD, CAT, APX, and glutathione

S-transferase increased but decreased at high doses. At high doses, PSII-inhibiting herbicides can impair the transport of photosynthetic electrons and compromise the antioxidant defense system. This occurs due to the excessive production of ROS, potentially leading to protein degradation and other detrimental consequences. Our findings suggest that a similar pattern may apply to SBC.

Figure 1.

Effects of SBC on the growth of I. grandifolia plants over a 14-day experiment. The plants were watered with 50 mL of a nutrient solution at pH 6.0 every two days. The control plants were treated with the nutrient solution only. The experiment was conducted at 25 °C, with a 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod and a photon flux density of 500 μmol m–2 s–1.

Figure 1.

Effects of SBC on the growth of I. grandifolia plants over a 14-day experiment. The plants were watered with 50 mL of a nutrient solution at pH 6.0 every two days. The control plants were treated with the nutrient solution only. The experiment was conducted at 25 °C, with a 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod and a photon flux density of 500 μmol m–2 s–1.

Figure 2.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on 14-day-old I. grandifolia plants. Light-response curve parameters include A) maximum net photosynthetic rate (PNmax), B, light-saturation point (LSP), C, light-compensation point (LCP), D, day respiration rate (RD), and E, photosynthetic quantum yield (α). CO2-response curve parameters include F) maximum carboxylation rate of Rubisco (Vcmax), G, photosynthetic electron transport rate (J), H, triose phosphate utilization (TPU), I, dark respiration rate (RD’), and J, mesophilic conductance (gm). Mean values (n = 5 ± SEM for A to E; n = 6 ± SEM for F to J) significantly different from the control are marked with **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, according to the Student’s t-test.

Figure 2.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on 14-day-old I. grandifolia plants. Light-response curve parameters include A) maximum net photosynthetic rate (PNmax), B, light-saturation point (LSP), C, light-compensation point (LCP), D, day respiration rate (RD), and E, photosynthetic quantum yield (α). CO2-response curve parameters include F) maximum carboxylation rate of Rubisco (Vcmax), G, photosynthetic electron transport rate (J), H, triose phosphate utilization (TPU), I, dark respiration rate (RD’), and J, mesophilic conductance (gm). Mean values (n = 5 ± SEM for A to E; n = 6 ± SEM for F to J) significantly different from the control are marked with **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, according to the Student’s t-test.

Figure 3.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on 14-day-old I. grandifolia plants. Gas exchange measurements and chlorophyll a fluorescence include A) transpiration rate (E), B) intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), C) stomatal conductance (gs), D) quantum yield of photosystem II photochemistry (ϕPSII), E) electron transport rate through PSII (ETR), F) photochemical quenching coefficient (qP), G) nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ), and H) effective photochemical quantum efficiency (Fv’/Fm’). Mean values (n = 6 ± SEM) significantly different from the control are marked with *p ≤ 0.05, according to the Student’s t-test.

Figure 3.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on 14-day-old I. grandifolia plants. Gas exchange measurements and chlorophyll a fluorescence include A) transpiration rate (E), B) intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), C) stomatal conductance (gs), D) quantum yield of photosystem II photochemistry (ϕPSII), E) electron transport rate through PSII (ETR), F) photochemical quenching coefficient (qP), G) nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ), and H) effective photochemical quantum efficiency (Fv’/Fm’). Mean values (n = 6 ± SEM) significantly different from the control are marked with *p ≤ 0.05, according to the Student’s t-test.

Figure 4.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on 14-day-old I. grandifolia plants after 10 h of dark adaptation. Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements include A, minimal fluorescence yield (F0), B, maximum fluorescence yield (Fm), C, variable fluorescence (Fv), and D, maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm). Mean values (n = 8 ± SEM) significantly different from the control are marked with **p ≤ 0.01, according to the Student’s t-test.

Figure 4.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on 14-day-old I. grandifolia plants after 10 h of dark adaptation. Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements include A, minimal fluorescence yield (F0), B, maximum fluorescence yield (Fm), C, variable fluorescence (Fv), and D, maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm). Mean values (n = 8 ± SEM) significantly different from the control are marked with **p ≤ 0.01, according to the Student’s t-test.

Figure 5.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on 14-day-old I. grandifolia plants. A, chlorophyll (SPAD index), and B, chlorophyll a fluorescence transient (OJIP curve). In B, the fluorescence levels F0, FJ, FI, and Fm are represented by points O, J, I, and P, respectively, at times of 50 µs, 2 ms, 30 ms, and tFm equal to 200 ms (peak at 650 nm). Mean values (n = 8 ± SEM for A; n = 10 ± SEM for B) significantly different from the control are marked with *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, and ***p ≤ 0.001, according to the Student’s t-test.

Figure 5.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on 14-day-old I. grandifolia plants. A, chlorophyll (SPAD index), and B, chlorophyll a fluorescence transient (OJIP curve). In B, the fluorescence levels F0, FJ, FI, and Fm are represented by points O, J, I, and P, respectively, at times of 50 µs, 2 ms, 30 ms, and tFm equal to 200 ms (peak at 650 nm). Mean values (n = 8 ± SEM for A; n = 10 ± SEM for B) significantly different from the control are marked with *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, and ***p ≤ 0.001, according to the Student’s t-test.

Table 1.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on length, fresh mass, and dry mass of roots, stems, and leaves of I. grandifolia plants grown for 14 days.

Table 1.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on length, fresh mass, and dry mass of roots, stems, and leaves of I. grandifolia plants grown for 14 days.

| |

SBC (mM) |

Root |

Stem |

Leaf |

| Length (cm) |

0 |

21.22 ± 0.97 |

6.02 ± 0.67 |

5.60 ± 0.16 |

| |

1.0 |

14.87 ± 1.10* |

3.42 ± 0.21* |

4.02 ± 0.19* |

| Fresh mass (g) |

0 |

0.36 ± 0.02 |

0.30 ± 0.02 |

0.79 ± 0.05 |

| |

1.0 |

0.16 ± 0.02* |

0.12 ± 0.01* |

0.34 ± 0.03* |

| Dry mass (g) |

0 |

0.02 ± 0.001 |

0.02 ± 0.002 |

0.10 ± 0.007 |

| |

1.0 |

0.01 ± 0.001* |

0.01 ± 0.001* |

0.05 ± 0.004* |

Table 2.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on the levels of reactive oxygen species, conjugated dienes, and malondialdehyde and the activities of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase of roots and leaves of I. grandifolia plants grown for 14 days.

Table 2.

Effects of 1.0 mM SBC on the levels of reactive oxygen species, conjugated dienes, and malondialdehyde and the activities of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase of roots and leaves of I. grandifolia plants grown for 14 days.

| |

SBC (mM) |

Root |

Leaf |

| Reactive oxygen species |

0 |

0.40 ± 0.068 |

4.40 ± 0.543 |

| (fluorescence μg−1) |

1.0 |

0.62 ± 0.035* |

6.61 ± 0.623* |

| Conjugated dienes |

0 |

1.79 ± 0.042 |

5.24 ± 0.414 |

| (μmol g−1) |

1.0 |

2,89 ± 0.163* |

9.27 ± 0.639* |

| Malondialdehyde |

0 |

1.90 ± 0.067 |

19.7 ± 2.041 |

| (nmol g−1) |

1.0 |

2.48 ± 0.055* |

21.9 ± 1.707 |

| Superoxide dismutase |

0 |

0.01 ± 0.001 |

0.06 ± 0.004 |

| (U mg−1) |

1.0 |

0.01 ± 0.002 |

0.05 ± 0.003 |

| Catalase |

0 |

0.02 ± 0.004 |

0.13 ± 0.006 |

| (μmol min−1 mg−1) |

1.0 |

0.03 ± 0.004 |

0.14 ± 0.006 |

| Peroxidase |

0 |

0.10 ± 0.011 |

0.12 ± 0.018 |

| (μmol min−1 g−1) |

1.0 |

0.13 ± 0.003* |

0.16 ± 0.027 |