1. Introduction

The consumption of milk has long been recognized as an essential component of a balanced diet, providing vital nutrients such as calcium, protein, and vitamins [

1,

2]. However, recent trends indicate a decline in milk consumption [

3]. Specifically, data reveals a 2% reduction in milk consumption within the EU between 2013 and 2018, with projections indicating a continued decline [

4]. This trend is particularly pronounced in Italy. In the past half-decade, Italian households have experienced a 7% reduction in milk purchases, primarily impacting fresh milk, followed by long-life milk (Ultra High Temperature - UHT treated milk) [

5,

6]. Despite initial signs of UHT milk consumption rebounding during the Covid-19 pandemic, consumption resumed its downward trajectory in 2020/2021 [

7]. This data, gathered from nationwide surveys, indicates a notable shift in consumer preferences away from traditional dairy products. Furthermore, market research conducted by Euromonitor International (2022) [

8] supports this observation, indicating a steady decrease in the sales of conventional milk products across various retail channels in Italy. The data suggests a growing consumer inclination towards plant-based milk alternatives, such as almond milk, soy milk, and oat milk, raising concerns about its implications for public health and dairy industry sustainability.

One of the factors contributing to this decline is the changed perception of milk quality by citizen-consumers, which has determined a significant cultural and communication gap between them, dairy producers and processors [

4]. A recent systematic literature review highlighted how consumer, farmers and processors have different representation related to milk quality, leading to a disconnect between citizen-consumer expectations and industry practices [

9]. Indeed, while farmers and processors demonstrated a comparable understanding of milk quality by emphasizing technical criteria, citizen-consumers, on the contrary, tended to have simpler and more subjective opinions that were difficult to measure quantitatively. Dairy experts, including farmers and processing specialists, emphasized that milk quality is ensured through careful attention to animal welfare, which involves practices such as disease monitoring, pathogen detection through milk testing, appropriate treatment methods, and effective mastitis management strategies. Conversely, citizen-consumers argued that milk quality is primarily linked to the well-being of animals, emphasizing their natural behaviors such as grazing and consuming grass. Moreover, while experts focused on the nutritional value of milk, considering factors like energy, protein, and calcium content, citizen-consumers prioritized the absence of additives and the naturalness of the product when defining milk quality. These findings align with prior research indicating that citizen-consumers are placing a growing emphasis on scrutinizing nutritional content, preferring products without harmful additives, and assessing the overall health and environmental implications of their consumption choices [

10]. Recent studies have underscored the impact of health and animal welfare concerns on citizen-consumer attitudes toward milk, affecting consumption behaviors [

11]. Moreover, sustainability and ethical considerations have become increasingly influential in shaping perceptions of food quality, with citizen-consumers prioritizing environmentally sustainable production methods, fair trade principles, and animal welfare standards [

12].

However, these studies were conducted using secondary data or cross-sectional survey. While valuable, these approaches may overlook nuanced insights that can be gleaned from more spontaneous and direct forms of communication, such as social media platforms [

13]. The utilization of social media platforms for generating and sharing information and opinions represents a valuable asset for understanding people’s perceptions and sentiments across various sectors of society [

14,

15]. Increasingly, people are turning to the internet for diverse activities, ranging from information retrieval to online transactions. Social media platforms, in particular, serve as virtual hubs for exchanging opinions and information, making them rich sources of citizen-consumer insights [

16] and emotions [

17]. Moreover, social media provide opportunities to gain valuable insights into people perceptions of product attributes [

18]. Additionally, people are often more inclined to express their opinions about products on social media platforms rather than through traditional surveys [

19]. By analyzing the content of social media, it is possible to glean insights into people attitudes toward specific issues or products. Social media marketing operates on the premise that social media content is a dialogue initiated by citizen-consumers, audiences, or businesses [

20]. The interactive nature of communication on social media enables companies and citizen-consumers to learn from each other about the practical use of products [

21]. Social media platforms serve as arenas for information exchange, communication, and engagement [

22]. Overall, leveraging social media as a research tool offers a dynamic and comprehensive approach to understanding the multifaceted dimensions of product attributes, comparing different points of view. Although this methodology has been used to investigate people perceptions of different food products [

13,

23], to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies conducted on social media that investigate the prospectives that citizen-consumers, processors, and farmers have regarding the concept of milk quality.

Based on these premises, it is crucial for the dairy industry to understand and explore the societal perspective on milk quality, as emphasized by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) [

24]. In particular, it is essential to examine the new perceptions and quality characteristics of citizen-consumers regarding milk quality and determine if they align with those of experts such as farmers and processors, utilizing diverse research methods including social media analysis. This understanding is vital for product development and the creation of marketing strategies that address the constantly evolving preferences and demands of citizen-consumers [

25,

26].

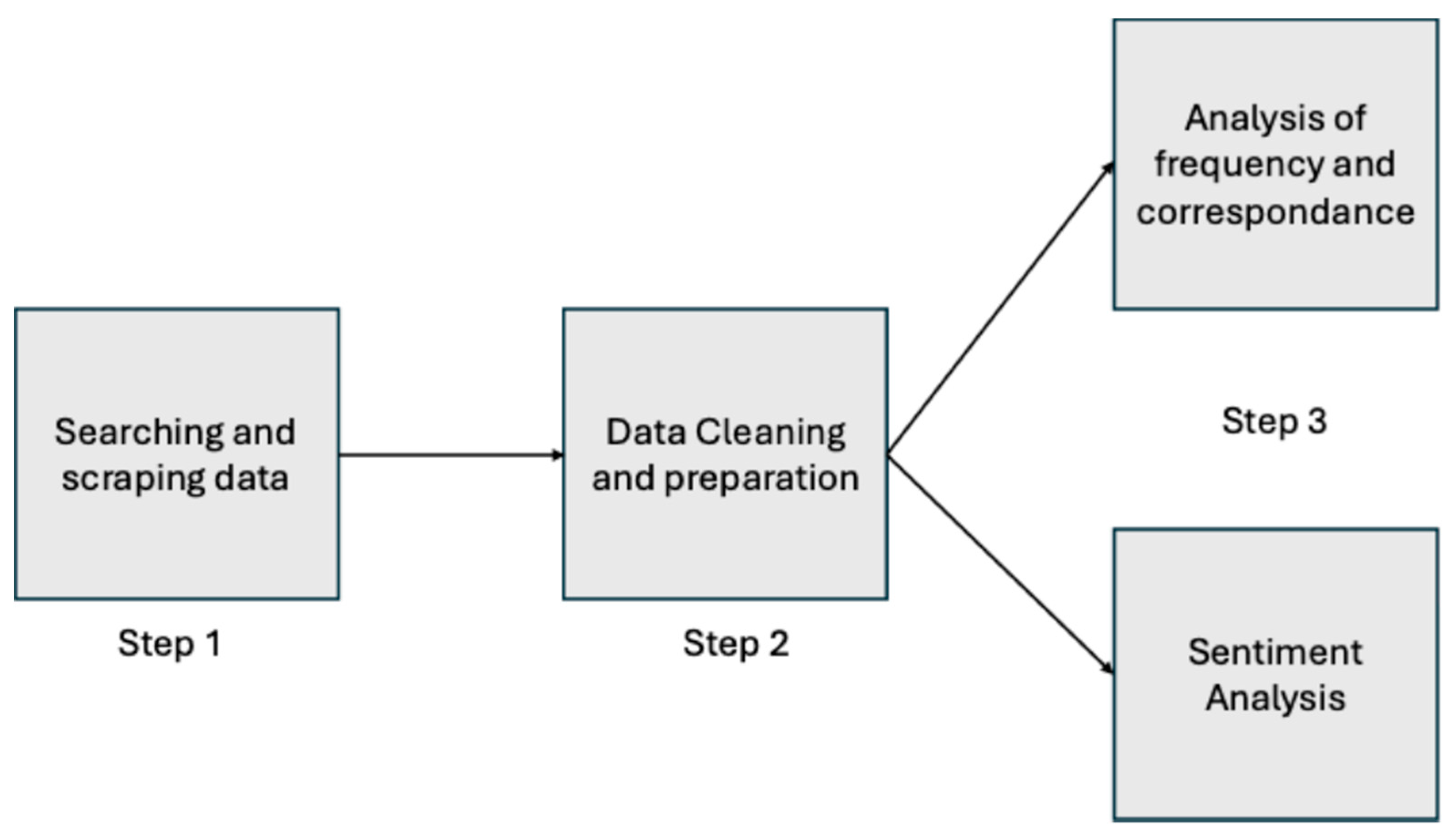

To bridge these knowledge gaps, the objectives of this study are: (a) To shed light on how citizen-consumers , farmers, and processors perceive and discuss milk quality through the analysis of spontaneous comments and discussions on Social Media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube; (b) To investigate the disparities and parallels in how milk quality is perceived among these actors.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Text Units

The scraping procedure resulted in a total of 19906 text units composed of comments and posts. After the cleaning procedure, the total number of text units dropped to 15508. Most comments were written by consumers (n=13410, 87%) followed by processors (n=1218, 8%) and farmers (n=850, 5%). Farmers posted their discussions on milk quality mainly on Facebook, specifically on pages dedicated to industry magazines and within farmer groups. Processors’ comments on milk quality were found on their company pages on Facebook. Consumers’ comments appeared on Facebook within consumer association pages, pages of large dairy companies, and in response to news from major news outlets. Additionally, consumer discussions on milk quality were also identified on YouTube in the form of videos or comments on videos.

3.2. Trend Over Time

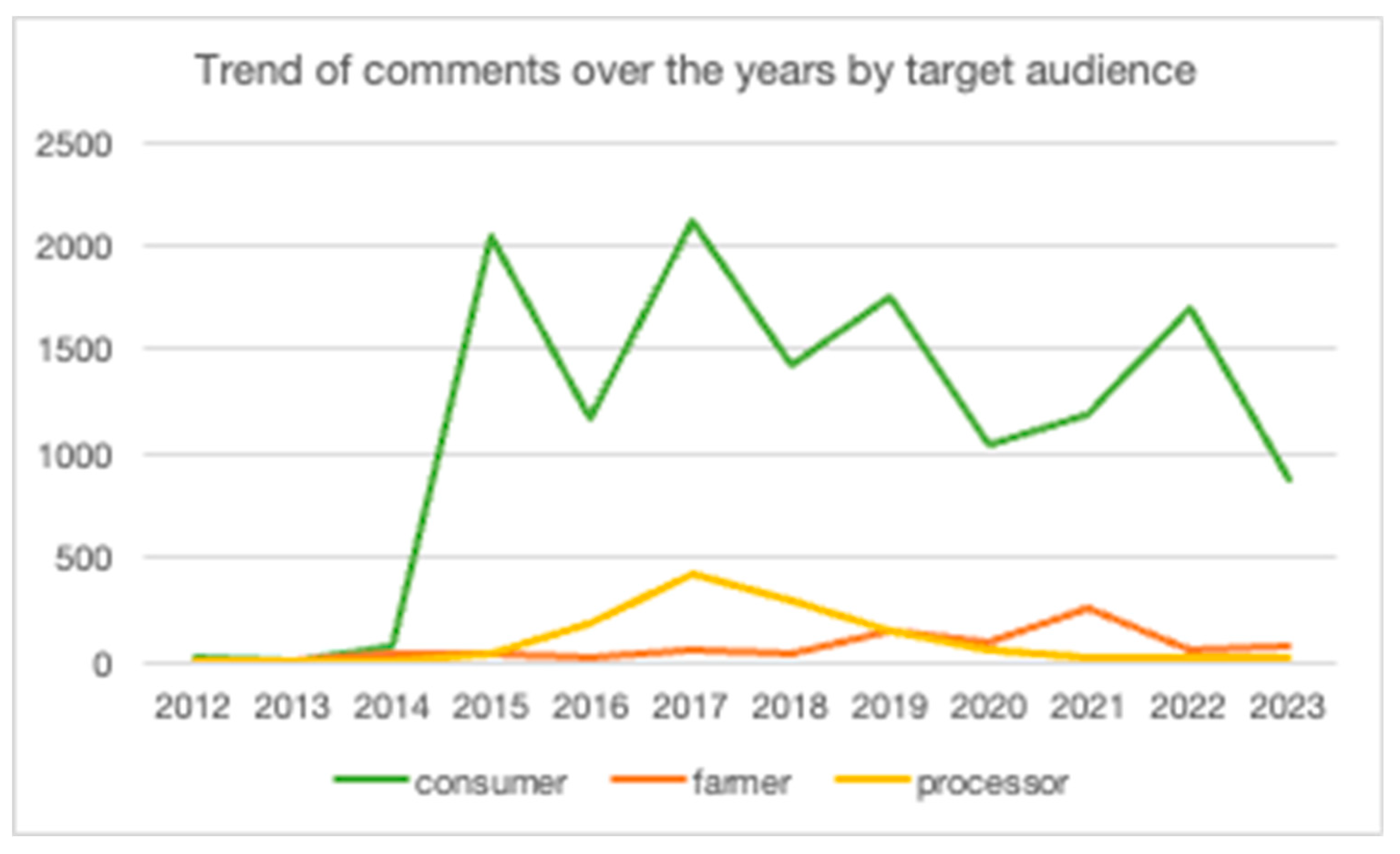

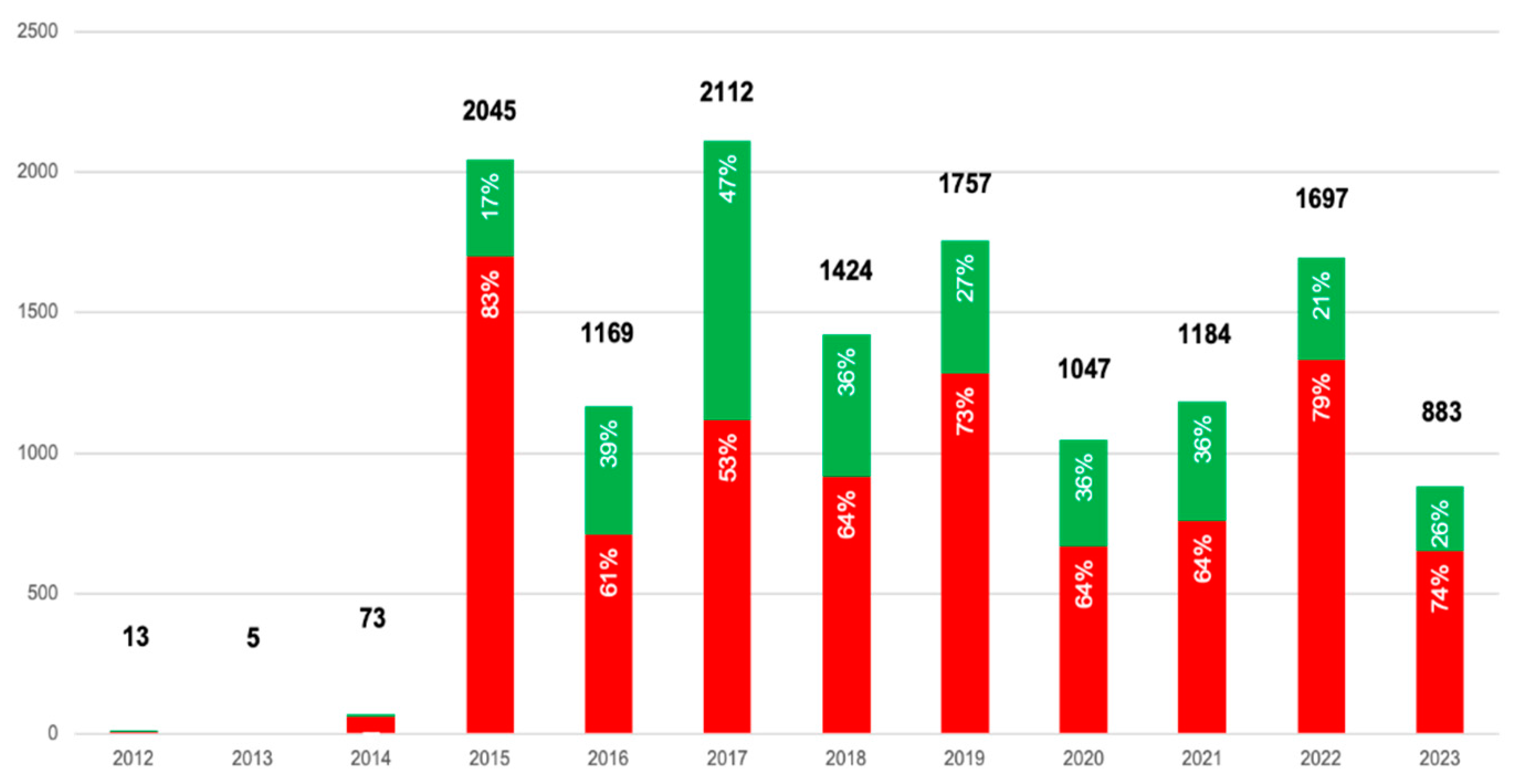

The comments retrieved have a time range from 2012 to 2023, but less than 1% of the comments from all three types of actors were made before 2014.

2017 saw the highest peak of total comments (2592) followed by 2019 (2062) as can be seen in

Figure 2. It is also interesting to note that the 2017 peak is evident for consumers and processors but not for farmers, whose main peak is in 2021 when almost 30% of the comments are found (251).

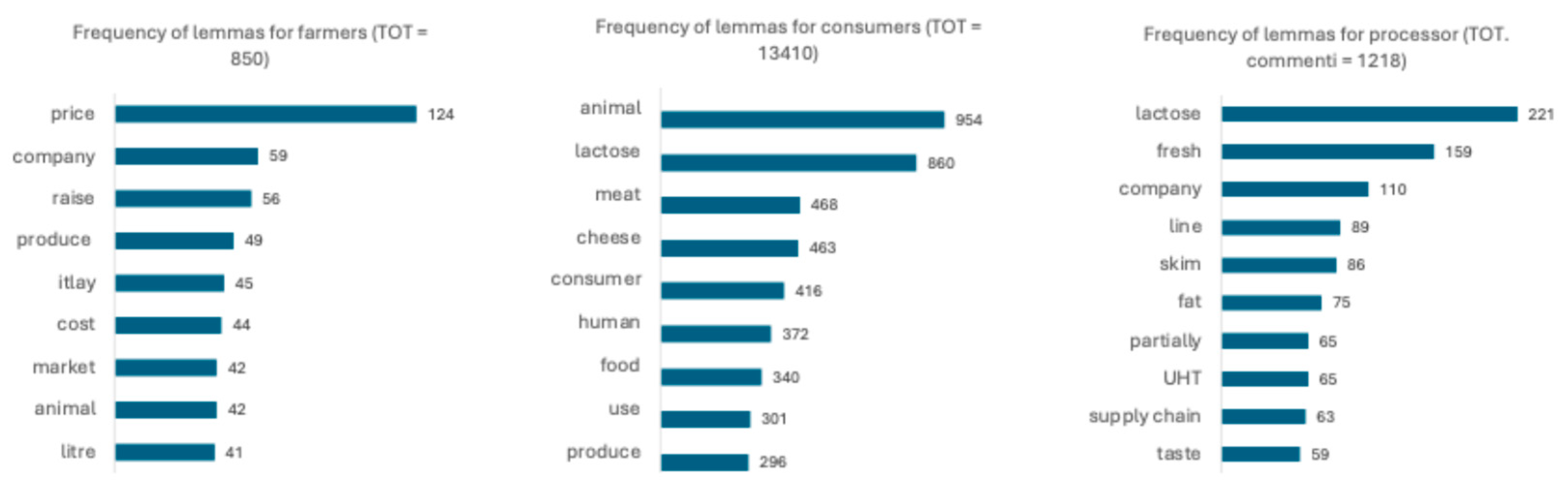

3.3. Analysis of Frequency

The analysis of the frequencies of the lemmas per type of actor included in this study shows clear differences that can be traced back to different discourses. In fact, as shown in

Figure 3, in the case of farmers the three most used words were price, company and raise, while in the case of consumers the most used words were animal, milk and meat, finally, the processors most used the words lactose, fresh and company.

In the case of farmers, the lemmas prices, costs, increase, company and production are to be found in controversies over rising costs and the economic unsustainability of production, in a logic whereby the dichotomy between quality and quantity production is often created. Furthermore, the Italian character of production emerges as a synonym for quality.

«as long as the product you make is priced by others, it will always be a miserable business»

«if you start doing the accounts with the pen tomorrow morning you close the company»

«But are we sure that our milk is better, ‘more quality’? Do we have proof of what we have been repeating for years like a mantra or is it the usual way of saying it?»

In the case of consumers, on the other hand, the issue of animal welfare is often prevalent, which with different logic is also linked to the issue of environmental sustainability. Furthermore, lactose, often defined as harmful to health, is a prevalent theme.

«I hope it is true that you use Italian milk. We have the best and most excellent stuff and quality in the world and we go and get it from abroad, rotting our good stuff.»

«For almost a year now, I have given up cow’s milk in favour of lighter rice milk - it’s a different world. I feel more energetic and full of energy right from the morning, whereas before I always had a feeling of drowsiness that accompanied me in the first few hours after waking up.»

«poor animals in whose hands...»

Finally, in the case of processors, a mirroring effect can be observed whereby the topic of lactose is strongly re-emphasised by promoting their lactose-free products through social communication, mentioning it even more often than the freshness of milk. Just as the Italian character of the milk is emphasised to define its quality.

«Have you ever tried #xxx milk? It is particularly

suitable for people like you who are intolerant and want an easy-to-digest milk that contains less than 0.1% lactose. This way, you won’t have to give up the rich nutritional properties and taste of real milk!»

«xxx has never imported milk from China, nor does it intend to do so. In fact, our mission is to offer our consumers a high quality product. For the sake of correct information, we also tell you that China produces a very low quantity of milk, not even enough for its own needs, so it is absolutely unthinkable to believe the false news that has been circulating these days. »

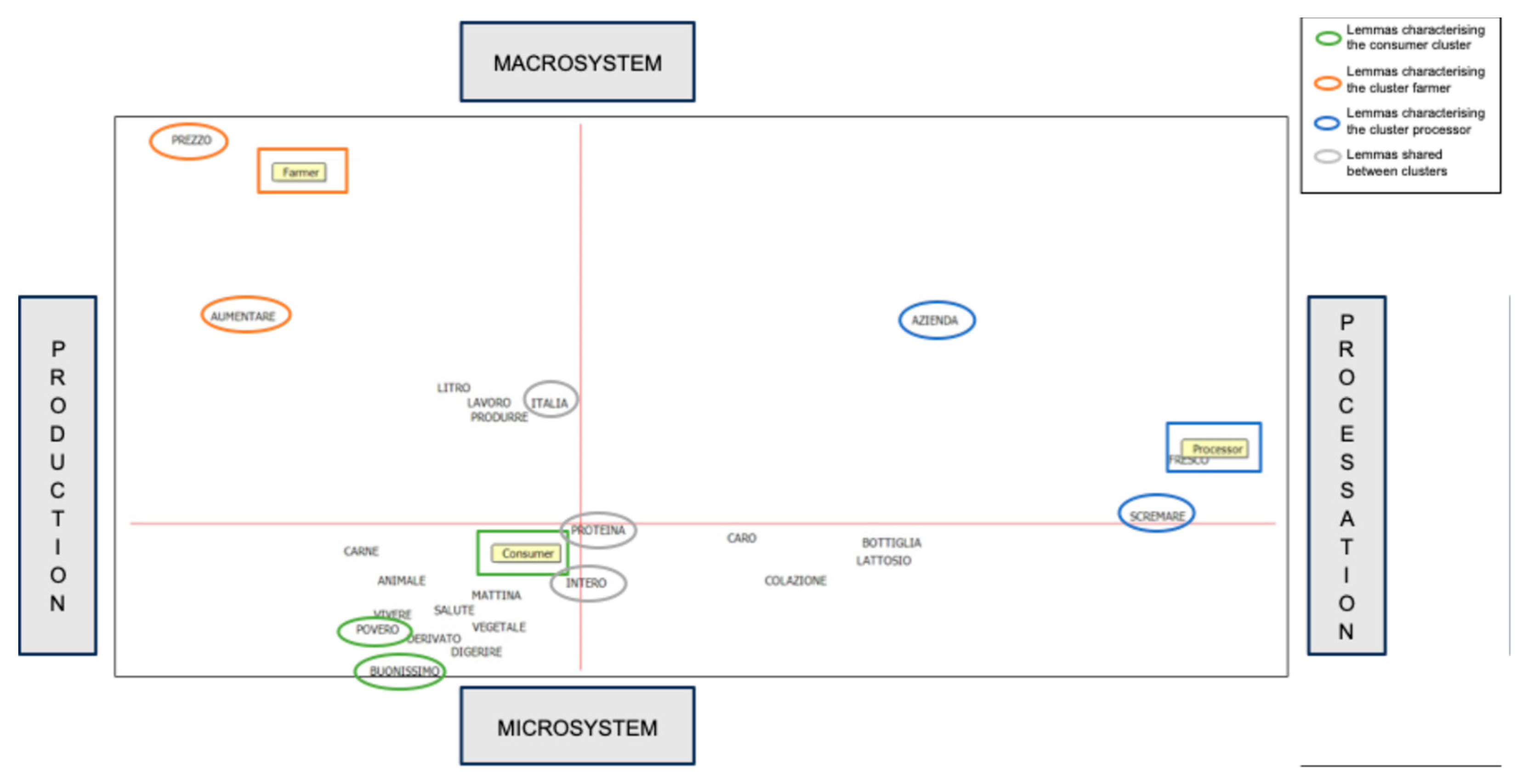

3.4. Correspondence Analysis

The correspondence analysis enabled the creation of a Cartesian plane to position the lemmas that most distinctly characterize the different roles, circled in

Figure 4. In this plane, the x-axis can be considered a continuum ranging from production (on the left), which involves livestock farming and the actual production of milk, to processing (on the right), encompassing the transformation phases before consumption. The y-axis, on the other hand, can be viewed as a continuum from the macrosystem (at the top) to the microsystem (at the bottom). The macrosystem refers to large-scale, overarching factors and entities, such as industry-wide practices and regulations, whereas the microsystem pertains to smaller-scale, localized elements, and particularly the product. On this level, it can be observed that farmers are in the macrosystem- and production-oriented quadrant, as their discourses are very much centered on price (“prezzo”) and increasing costs (“aumentare”). While consumers are in the micro-system and production-oriented quadrant, in fact, differentiating this group are words referring to the product as poor (“povero”) and good (“buonissimo”). Finally, on the opposite side emerge the processors, particularly process-oriented but not too polarised towards the macrosystem or micro-system and characterised by the words company (“azienda”) and skim (“scremare”).

3.5. Sentiment Analysis

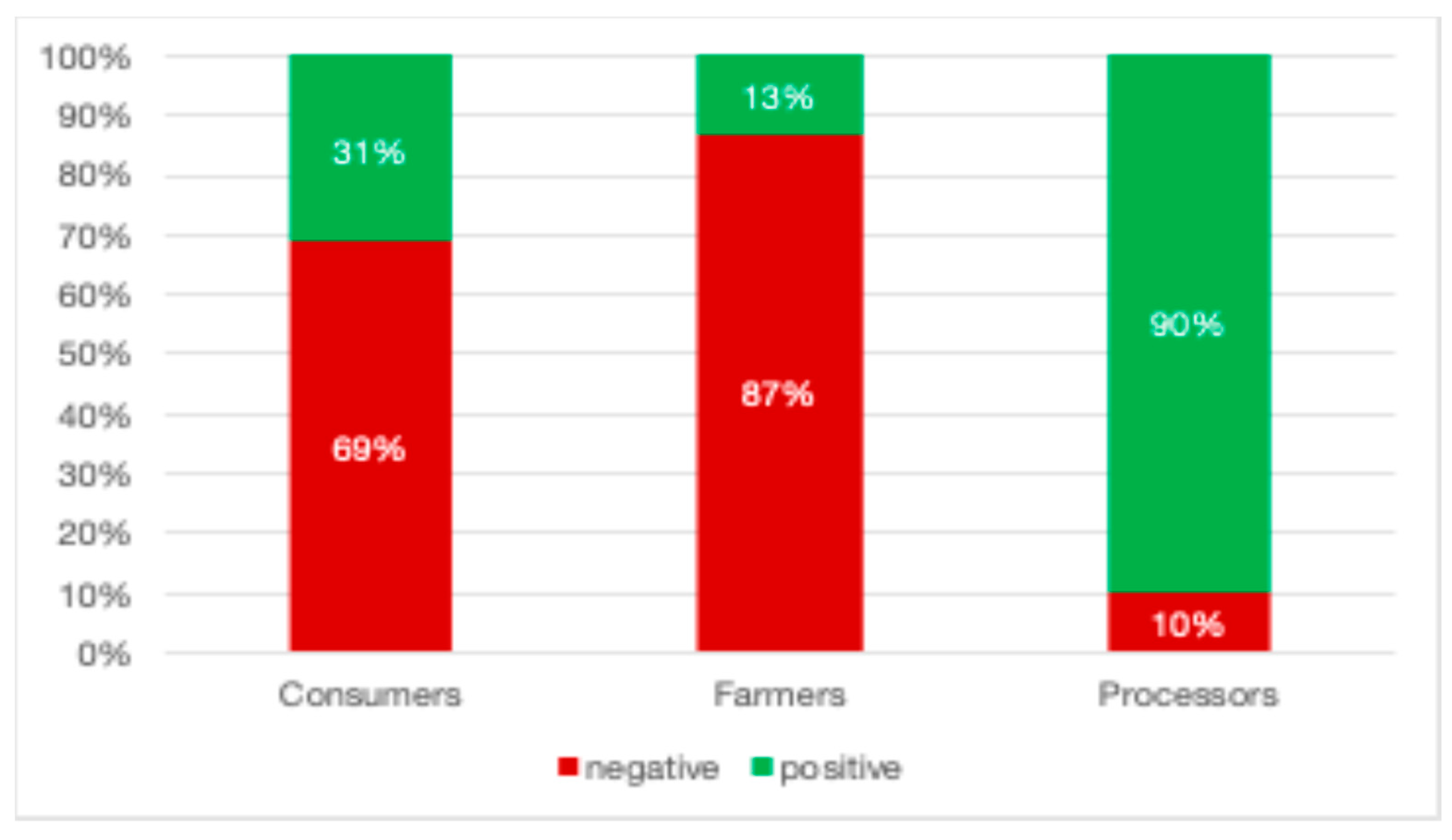

The sentiment analysis revealed significant differences among the three groups (

Figure 5).

For the farmers, almost all comments were negative (87%), while for the processors, the opposite was true, with nearly all comments being positive (90%). In contrast, the consumers presented a more mixed picture, with 69% of comments being negative and 31% positive. It is noteworthy, moreover, that if this proportion remain quite stable for processors and farmers, while for consumers it changed during the years (

Figure 6). In particular, if looking at the three main peaks of comments, there’s a evident difference of positive sentiment among them, whereby in the 2015 only 17% of the comments resulted with a positive sentiment, while in the 2017 almost half (47%) and in 2019 about a third (27%).

4. Discussion

This research has provided a comprehensive and ecological snapshot of the actual spontaneous social discourses surrounding milk quality taking place online, shedding light on the underlying reasons behind the declining milk consumption observed in Italy in recent years [

30]. By analyzing spontaneous comments on social media, we have gained valuable insights into the perspectives of consumers, farmers, and processors regarding milk quality.

The differentiation in platform usage among stakeholders aligns with findings from previous studies that emphasize how social media platforms serve as distinct communication channels for various food actors [

31]. Farmers often utilize industry-specific groups and pages to discuss production-related issues, reflecting a need for targeted communication within their professional community [

32]. Processors’ preference for company pages to promote their products and engage with customers echoes findings by Kao et al. 2016 [

33], which suggest that processors use social media primarily for marketing and customer relations. Consumers’ widespread engagement on consumer association pages and major news outlets parallels the observations by Samoggia et al. (2020) [

34], indicating that these platforms are pivotal for raising awareness and discussing quality and ethical issues.

The peaks in discussion, notably in 2017 for consumers and processors, and 2021 for farmers, can be contextualized with industry events or crises that typically drive online discourse. In those years, in fact, several articles were published in the most important Italian newspapers about the heavy accusations levelled at some Italian dairy companies involved in false certifications that tried to cover up the presence of aflatoxins in milk [

35] above the legal limits. These temporal spikes underscore the reactive nature of online discussions, where significant industry events prompt increased dialogue.

Considering the topics used by different actors to talk about milk quality, results reveal distinct discourses among the stakeholders, with farmers focused on economic issues, consumers on animal welfare and health (milk origin and lactose free product), and processors on product attributes like lactose content and freshness, mirroring the most important consumers’ topics. The results concerning consumers are corroborated by past research that showed that how animal welfare significantly influences consumers’ hedonic and emotional reactions to milk, increasing the intention to buy it [

36] Moreover, the emphasis on the product’s origin highlights consumers’ preference for locally sourced milk, perceived to be of higher quality and safer as well documented by Canavari et al. (2015) [

37].

The importance given by farmers to issues concerning the economic aspects of their farms reflects the problems that farmers are experiencing in Italy. Recent research has shown that in 3411 Italian farms (54% of the sample), the farm net income is lower than the reference income for family work, jeopardising the survival of these farms [

38].

Finally, processors take up the same consumer themes and leverage them to sponsor their products. An example of this is the increasing presence of advertisements and communications emphasising the production of lactose-free milk to foster a positive consumer behavioural intention towards these products [

39]. Communication by these actors is therefore not disinterested but, on the contrary, strategically oriented towards profit and sales.

Furthermore, these differences are emphasised by the results of the correspondence analysis. They showed that the contents of the discourses concerning quality milk expressed by the different groups belong to distinct focus areas and operational scopes of each target. Indeed, the farmers’ discourses about milk quality are more focused on production and macrosystem aspects related to economic issues, consumers’ topics are focused on production aspects related to milk emphasising microsystem aspects i.e., more related to intrinsic product qualities while processors are more focused on technical processing aspects related to milk. This highlights how each of these targets not only talks about different topics concerning milk quality but also about different subject areas and social systems. This supports the framework proposed by Bronfenbrenner (1979)[

40], where different actors operate within nested systems, influencing and being influenced by both micro and macro-level factors.

The communication gap between these three actors is particularly evident from the differing sentiment scores. While processors attempt to address consumer concerns, their overwhelmingly positive sentiment contrasts sharply with the more negative sentiments expressed by farmers and consumers. This discrepancy suggests a misalignment in the communication strategies of processors, who may not fully resonate with the critical and concerned tones of the other actors. Farmers, in particular, stand out as having the most negative sentiments, reflecting their frustrations with economic pressures and the perceived disconnect between their efforts and consumer expectations. This variation corroborates findings by Whitaker (2024) [

41], who found that economic pressures often lead to negative sentiments among farmers, whereas positive sentiment among processors can be attributed to marketing efforts that highlight positive aspects of their products [

42]. The fluctuating consumer sentiment over time is consistent with findings by Shayaa et al. (2018) [

43], who observed that consumer sentiment can be highly volatile and influenced by external events and media reports. This suggests that fostering direct communication and discussions among these three groups could enhance mutual understanding, improve attitudes, and possibly lead to more aligned and effective production practices.

Finally, it is interesting to reflect on the value of research based on spontaneous discourse from social media, highlighting aspects that cannot be fully understood using other methodologies. In fact, a recent systematic literature review conducted by Castellini et al. (2023)[

9], with the same objectives as this study, reported only partially overlapping results. In this study based on social media, topics related to the concept of milk quality seem to align more closely with the common discussions among the various stakeholders. For instance, economic concerns are almost universally present in the spontaneous social media discussions of farmers, an aspect that does not emerge in the systematic literature review. However, these issues are well-documented and genuinely exist among Italian farmers [

38]. This evidence emphasises the need for more research using social media to understand people’s real perceptions and attitudes towards certain issues, especially if they emotionally involve the participants and disguise a negative feeling that might be hidden in other research contexts.

Despite these strengths, the present study has some limitations. The study’s reliance on social media data may introduce sampling bias, as it primarily captures the opinions and sentiments of users active on these platforms, potentially excluding those not engaged online. Moreover, findings may not be fully representative of the broader population due to the selective nature of social media users and their demographics, which could skew the results. Finally, due to the breadth of data sources and topics covered, the study may not delve deeply enough into specific aspects of milk quality discourse, potentially overlooking deeper insights.

In conclusion, our study highlights significant gaps and areas of alignment in the perceptions of milk quality among consumers, farmers, and processors. The findings offer practical application, suggesting that enhancing communication and understanding among these groups could lead to more effective strategies for addressing consumer concerns, thereby potentially reversing the declining trend in milk consumption. By focusing on the real-world issues discussed online, stakeholders can develop more targeted and relevant marketing and production strategies that better meet the evolving demands of today’s consumers. Future research could benefit from longitudinal studies to track evolving consumer, farmer and processor perception about milk quality, considering the influence of external factors. Cross-cultural comparisons would provide insights into regional variations in milk quality perceptions. Finally, integrating social media analysis with traditional research methods like surveys could validate findings and offer deeper insights into stakeholder viewpoints.