Submitted:

06 July 2024

Posted:

09 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Case I) with independent random sample size. The basic risks and sample size index are supposed to be independent and converges weakly to a non-degenerate distribution function [9];

- Case II) with non-independent random sample size. There exists a positive-valued variable V such that converges to V in probability, allowing the interrelation of the basic risk and sample size index [19].

2. Main Results

2.1. Limit theorem for Case I) with independent sample size

- (i).

- If condition (11) holds with two positive constants α and β, then

- (ii).

-

The following limit distribution holdsprovided that one of the following four conditions is satisfied (notation: , the right endpoint of )

- a).

- When is one of the same p-types of , and is one of the same p-types of .

- b).

- When is one of the same p-types of , and is one of the same p-types of for . In addition, Eq.(11) holds with and .

- c).

- When is one of the same p-types of , and is the same type of for . In addition, Eq.(11) holds with and or and .

- d).

- When both and are one of the same p-types of . In addition, Eq.(11) holds with and or and .

2.2. Limit theorem for Case II) with non-independent sample size

3. Discussion

3.1. Extreme Limit Theory for Competing Minima Risks

- (i).

- If condition (11) holds with two positive constants α and β, then

- (ii).

-

The following limit distribution holdsprovided that one of the conditions a)∼ d) in Theorem 2 holds.

3.2. Examples

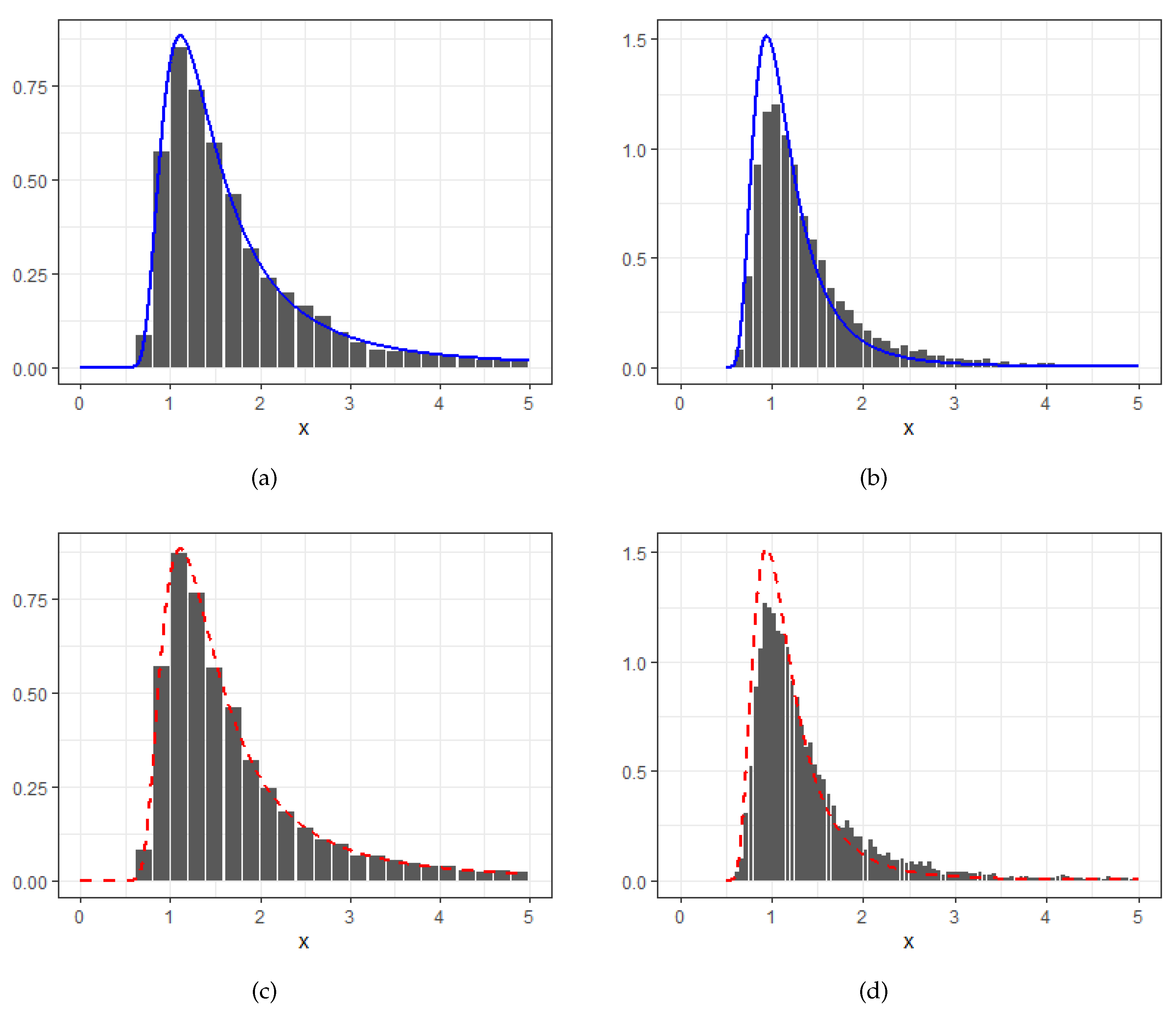

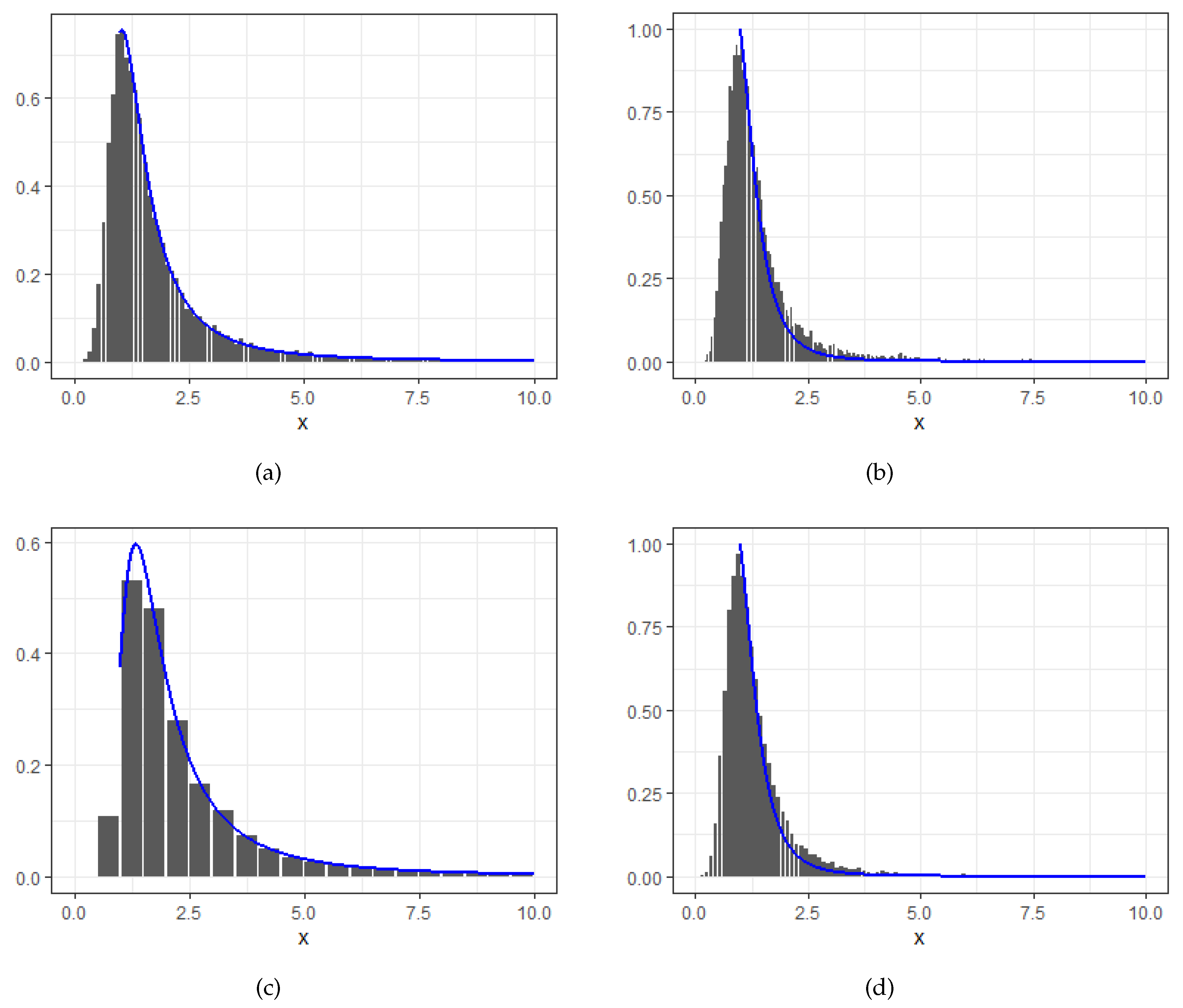

4. Numerical Studies

- (1)

- For or with , we have

- (2)

- For with , we have

- (1)

- For or with , we have

- (2)

- For with , we have

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A Proofs of Theorems 1 ∼ 4

References

- Abd Elgawad, M., Barakat, H., Qin, H., and Yan, T. (2017). Limit theory of bivariate dual generalized order statistics with random index. Statistics, 51(3):572–590. [CrossRef]

- Barakat, H. and Nigm, E. (2002). Extreme order statistics under power normalization and random sample size. Kuwait Journal of Science & Engineering, 29(1):27–41.

- Beirlant, J. and Teugels, J. L. (1992). Limit distributions for compounded sums of extreme order statistics. Journal of Applied Probability, 29(3):557–574. [CrossRef]

- Berman, S. M. (1962). Limiting distribution of the maximum term in sequences of dependent random variables. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 33(3):894–908.

- Cao, W. and Zhang, Z. (2021). New extreme value theory for maxima of maxima. Statistical Theory and Related Fields, 5(3):232–252. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q., Xu, Y., Zhang, Z., and Chan, V. (2021). Max-linear regression models with regularization. Journal of Econometrics, 222(1, Part B):579–600. [CrossRef]

- Dorea, C. C. and GonÇalves, C. R. (1999). Asymptotic distribution of extremes of randomly indexed random variables. Extremes, 2(1):95–109.

- Embrechts, P., Kluppelberg, C., and Mikosch, T. (1997). Modelling Extremal Events. Stochastic Modelling and Applied Probability. Springer, Heidelberg.

- Galambos, J. (1978). The Asymptotic Theory of Extreme Order Statistics. Wiley series in probability and mathematical statistics. Wiley, New York.

- Grigelionis, B. (2004). On the extreme-value theory for stationary diffusions under power normalization. Lithuanian Mathematical Journal, 44:36–46. [CrossRef]

- Hashorva, E., Padoan, S. A., and Rizzelli, S. (2021). Multivariate extremes over a random number of observations. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 48(3):845–880.

- Hu, K., Wang, K., Constantinescu, C., Zhang, Z., and Ling, C. (2023). Extreme limit theory of competing risks under power normalization. arXiv: 2305.02742.

- Korolev, V. and Gorshenin, A. (2020). Probability models and statistical tests for extreme precipitation based on generalized negative binomial distributions. Mathematics, 8(4):604. [CrossRef]

- Leadbetter, M. R., Lindgren, G., and Rootzén, H. (1983). Extremes and related properties of random sequences and processes. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Nasri-Roudsari, D. (1999). Limit distributions of generalized order statistics under power normalization. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods, 28(6):1379–1389.

- Pantcheva, E. (1985). Limit theorems for extreme order statistics under nonlinear normalization. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Peng, Z., Jiang, Q., and Nadarajah, S. (2012). Limiting distributions of extreme order statistics under power normalization and random index. Stochastics, 84(4):553–560. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z., Shuai, Y., and Nadarajah, S. (2013). On convergence of extremes under power normalization. Extremes, 16(3):285–301. [CrossRef]

- Ribereau, P., Masiello, E., and Naveau, P. (2016). Skew generalized extreme value distribution: Probability-weighted moments estimation and application to block maxima procedure. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods, 45(17):5037–5052. [CrossRef]

- Shi, P. and Valdez, E. A. (2014). Multivariate negative binomial models for insurance claim counts. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 55:18–29. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A. A. (2000). Bayes prediction in a Pareto lifetime model with random sample size. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series D, 49(1):51–62. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z. and Wu, C. (2014). Limit laws for the maxima of stationary chi-processes under random index. Test, 23(4):769–786. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z. Q. (2014). The limit theorems for maxima of stationary Gaussian processes with random index. Acta Mathematica Sinica, 30(6):1021–1032. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. (2021). Five critical genes related to seven COVID-19 subtypes: A data science discovery. Journal of Data Science, 19(1):142–150. [CrossRef]

| 1 | The cdf of Pareto is given as . |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).