1. Introduction

One of the main challenges facing students is the unpredictability and globalization of information and knowledge [

1]. This problem is worsened by other factors, like the speed at which science and technology are developing and climate change, which suggests that millions of people’s physical and mental well-being is declining [

2]. The research on society’s problems in the twenty-first century is unequivocal: citizens need instruments to create more equitable, resilient, and sustainable societies. One significant document that underscores the importance of an adequate educational response to the numerous challenges confronting humanity is the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Consequently, it emphasizes the need to ensure sufficient educational resources to address the various issues facing society in this context [

3]. The 2015 year will be remembered as the beginning of the 2030 Agenda, which includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These 17 SDGs emphasize that no one should be left behind as they seek to meet the needs of people in both developed and developing nations by 2030. This study highlights Goal 4, “Quality Education: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” [

4].

When examining the school environment, we identify various dynamics influencing students’ academic performance. Among these, academic time management planning, the tendency to procrastinate, gender, and study hours emerge as critical variables. The ability to plan and organize time is fundamental to academic success, but not all students master it equally [

5] nor approach it with the same responsibility and conscientiousness [

6]. Academic procrastination (PR) can have a variety of complex causes and is frequently viewed as a crippling behavior. However, focusing on the conditions under which PR manifests is crucial, especially in educational practices that influence students’ standardized behaviors. These practices can either inhibit or facilitate PR development in studies [

7]. For sustainability in education, practices and approaches must ensure the continuity, equity, and quality of the educational process over time, focusing on the holistic development of students, the preservation of resources, and the promotion of a fair and informed learning environment [

8].

Thus, analyzing the variables under study raises pertinent questions: How do students manage their academic time? What leads some to diligently dedicate themselves to school tasks while others delay them until the last moment or leave them incomplete? Are there differences between boys and girls in this approach? Or is time management more closely linked to the hours they dedicate to study? How does PR evolve over study time regarding how students organize their academic time?

Oliveira et al. [

9] highlight that the preparation and organization of studies are essential pillars of the learning process. By planning their study times, students develop the ability to set goals, create strategies, and manage their time efficiently. Additionally, the organization ensures that students maintain concentration and focus during study sessions. The authors further emphasize that planning and organization are fundamental to academic performance.

Therefore, the teachers’ mission is to create deep, dynamic, and engaging learning environments that enhance students’ learning approach [

10]. Their teaching practices must be constantly renewed, recognizing that, in various educational contexts, there are no students with identical attitudes, behaviors, goals, feelings, or preparations. Instead, there is a diversity of individuals with different interests, skills, and motivations, which introduces new and complex challenges to teaching and learning [

11].

Nowadays, teachers must encourage active and constructive student engagement in learning, aiming for academic excellence [

12,

13]. This approach requires continuous adaptation to each student’s specificities, using innovative pedagogical strategies that meet their individual needs. Thus, education becomes a more inclusive and effective experience, capable of addressing the vast diversity in contemporary classrooms. Araújo (2023) [

14] highlights the usual neglect with which students approach school, their study habits, and the crucial motivation to self-regulate the time dedicated to school activities. This scenario concerns teachers and generates significant personal, social, and professional consequences for all involved in the educational process, from guardians to policymakers.

Lourenço and Paiva [

15] refer to implementing metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral strategies as key to combating school failure. These strategies allow students to experiment and evaluate the effectiveness of their study methods and learning strategies stimulated during the learning process. They also mention that students must acquire transferable knowledge, skills, and attitudes between different learning contexts, enabling them to structure their learning process more effectively. Thus, the knowledge acquired in various educational environments can be applied in various work situations. These practices promote students’ autonomy and responsibility and create a solid foundation for a successful and sustainable academic path.

Considering the active role of students, as suggested by recent research [

16,

17,

18], the questions raised about the constructs under analysis are justified, highlighting the need to examine them in their complexity. Students’ academic time management planning and PR are not merely isolated factors of concern in the school environment. These elements are part of a broader concept that encompasses multiple factors, such as the responsibility and motivation of the participants, the characteristics and composition of the class group, the psychosociological climate of the school, the personality and pedagogical action of the involved teachers, the curriculum and school practices, the very nature of school life, and family support [

19].

In each situation, it is possible to recognize that certain factors may weigh more on educational success than others, depending on their relevance and sustainability in the school context [

8]. Considering their psychological, sociological, and pedagogical functions, interpretations of the phenomenon can be varied and rich in nuances. Each case highlights the complexity and interaction of these multiple elements, which together shape students’ educational experiences.

Thus, understanding how academic time management planning and PR develop in students’ studies, including gender differences and the hours spent studying, became the first aim of this study, aiming for as broad and diverse an investigation as possible. The second aim was to develop some guidelines that would be useful for educational practice, highlighting the importance of these constructs in the students’ study process and promoting meaningful learning.

2. Review of the Literature and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Academic Time Management Planning

Research on study skills identifies academic time management planning as one of the essential pillars of learning strategies [

20,

21]. This time management, described by Casiraghi et al. [

22] as a planning behaviour, is closely linked to the perception of the effort required to tackle various learning challenges and is enhanced by motivation and goal setting.

According to Marcílio et al. [

18], academic time management planning is conceived as a goal-oriented process that involves evaluating time use, setting goals, planning, monitoring, and prioritizing tasks to achieve predefined objectives. These authors outline several phases to facilitate academic time management planning, including diagnosing time use, developing strategies to overcome difficulties, setting goals and objectives, and implementing and evaluating changes. As a result of these efforts, students become more competent and achieve better academic results [

23]. This analytical framework underscores the importance of effective time management as a catalyst for educational success, promoting an environment where strategic planning and continuous monitoring of academic activities are fundamental for academic excellence.

In the current educational landscape, as highlighted by Vega and Beyebach [

7], it is essential to understand students and implement diverse approaches and strategies that meet their specific needs, guiding them in organizing their studies and effectively managing their time for all school activities. An effective approach to overcoming these challenges is to avoid the “snowball” phenomenon, where initial responses to difficulties and well-intentioned efforts to resolve them intensify the problem, turning it into a chronic issue. The authors emphasize that the difference between academic success and failure is closely associated with factors such as the organization of time dedicated to academic activities, the study methods used, and the correlation between performance and effort invested. This understanding underscores the importance of careful monitoring and pedagogical strategies that enhance students’ abilities, promoting a more balanced and successful academic journey.

Thus, it can be said that the greater a student’s perception of control over the time invested in their school activities, the less stress they will experience. Various studies highlight the beneficial influence of time management competence on learning and academic outcomes [

5,

19,

22], providing students with the necessary tools to effectively structure and manage their tasks. This refined control mitigates anxiety and stress, allowing students to achieve a harmonious balance between study and leisure, and fosters a more productive and balanced learning environment. In this way, students are empowered to achieve better academic results. Proper planning prevents PR and task accumulation, promoting effective time management and school activities.

According to Matta [

24], students who successfully adapt to academic demands develop robust study habits, demonstrate efficient time management and meticulous content organization, and strategically use available learning resources. The author emphasizes that academic performance is closely linked to a student’s ability to actively engage in activities, plan effectively, meet deadlines, and maintain good study habits. This combination of factors facilitates adaptation to the school environment and promotes a more fruitful and balanced academic journey.

In a study conducted by Noro and Moya [

25], the results highlighted the significant influence of study hours on academic performance, revealing that students who dedicated more weekly study time achieved better exam results. Additionally, Lourenço and Nogueira [

26] demonstrated that female students exhibit more effective time management in school and tend to procrastinate less on their school tasks. Casiraghi et al. [

22] reinforce this idea by emphasizing that students must adopt learning strategies to achieve academic excellence and efficient time management. These strategies include self-assessment, content organization and transformation, goal setting and planning, effective information retrieval and recording, self-monitoring, study environment organization, seeking help, and continuous review.

Some studies highlight factors that can compromise effective study time management, such as inadequate study organization, poor test preparation, and inappropriate choice of study location [

5,

19,

22,

27]. Difficulty in concentration, often resulting from the absence of a suitable home environment that fosters attention dispersion and a lack of planning and preparation for activities necessary to achieve learning goals, are also significant [

28]. According to Júnior et al. [

10], of using appropriate resources enables students to develop satisfactory study habits, which are strongly linked to effective organization and planning of learning.

In the context of the intervention under study, Thibodeaux et al. [

29] suggest that students with exemplary academic performance tend to set clear goals, estimate the time required for task completion, and follow a meticulous study routine. These students habitually assess their progress systematically in the learning process, enabling them to minimize the effects of PR on their school activities. They implement effective strategies to adjust their behavior and adapt to the academic environment, thereby managing their time more efficiently. As a result of these efforts, they achieve a higher level of proficiency and consequently attain better academic outcomes [

30].

2.2. Procrastination

According to Costa Júnior et al. [

31], PR can be understood as the intentional decision to postpone an unappealing task despite being aware of the potential negative consequences of this choice. The authors suggest that when academic PR behaviour occurs, there is a clear failure in the student’s self-regulation process, hindering them from effectively managing their performance and meeting school demands. This recurring phenomenon is characterized by a tendency to delay or postpone tasks [

32]. Therefore, PR emerges not merely as a distraction but as a significant obstacle on the path to academic success.

According to Silva et al. [

5], PR manifests in various forms in daily tasks and across different contexts, with particular emphasis on academic PR, which is frequently observed despite its potential drawbacks for students. They further note that in this scenario, students exhibit behaviors such as delays in preparing and submitting assignments, neglecting activities, and intensive studying only on the eve of exams. This deliberate postponement of tasks can negatively impact the student’s academic performance [

33].

Procrastinators reveal themselves behaviorally through task avoidance, action delay, and postponement of activity completion, and cognitively or decisively, manifesting in indecision and deliberate delay in decision-making [

34]. These two types of PR are positively associated with affective responses and time perception while negatively related to internal stimulation [

35].

Generally, PR tends to be more frequent in scenarios where the volume and complexity of demands increase [

36]. Consequently, Fior et al. [

37] highlight that the causes of PR can be multiple: ineffective time management dedicated to school tasks, unfavorable environment, difficulty in concentration, anxiety about assessment, dysfunctional beliefs and thoughts, difficulty in facing obstacles, fear of failure, low frustration tolerance, and task execution difficulties. The authors emphasize that among the crucial variables associated with academic PR behavior are self-efficacy, autonomous learning regulation, and perfectionism.

According to Furlan and Martínez- Santos [

38], PR often reflects how an individual responds in evaluation situations, involving adaptive behaviors, such as maintaining focus during a test, and maladaptive behaviors, such as avoiding or delaying important tasks. For individuals with maladaptive perfectionistic traits, the tendency to use avoidance strategies is notable, often evidenced through PR [

39]. This pattern emerges when excessive fear of criticism or failure prevents the student from initiating or completing a task [

38].

In this context, Silva et al. [

28] emphasizes that research has identified PR as a maladaptive behaviour in academic contexts characterized by a lack of self-regulation that manifests in an active state of dysregulation. In this pattern, students tend to postpone or avoid unpleasant academic tasks, seeking immediate relief. These anxious behaviors ultimately delay academic progress, accumulate workload, and potentially result in academic failures, which can lead to dissatisfaction and academic performance below expectations [

40].

Therefore, PR, characterized by task postponement, is associated with ineffective time management in academics and students’ self-regulatory processes. This behaviour, prevalent in academic environments, is influenced by factors such as anxiety, perfectionism, and fear of failure. It leads to delays in the preparation and submission of assignments, compromises performance, and causes academic dissatisfaction.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

From the literature review, it is deduced that how students plan and manage the time dedicated to their school activities, both in the short and long term, has a predictive effect on their attitudes and behaviors towards PR in daily study or test preparation. Additionally, it is observed that gender and the hours students spend studying influence this management of school time. This association can reveal significant differences in study patterns between boys and girls, providing a deeper understanding of how each group organizes and dedicates themselves to studying. Accordingly, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1. Female students show a stronger tendency to plan their study time management in the short term compared to male students;

H2. Girls demonstrate a greater predisposition to plan their study time management in the long term than boys;

H3. Students who dedicate more hours to study exhibit a greater tendency to plan their study time management in the short term;

H4. Students who invest more time in studying are also more likely to plan their study time management in the long term;

H5. Students who engage in short-term planning of study time management also tend to do so in the long term;

H6. Students who pay attention to short-term planning of study time management tend to procrastinate more in daily study;

H7. Students who focus on short-term planning of study time management show a greater tendency to procrastinate in test preparation;

H8. Students who are more diligent in long-term planning of study time management tend to procrastinate less in daily study;

H9. Students who plan their study time management in the long term are less likely to procrastinate in test preparation; and

H10. Students who procrastinate in daily study also tend to procrastinate in test preparation.

Therefore, the absence of explanatory models drives the development of a proposal that investigates all aspects of the variables under study in greater depth. This is the main challenge that this research aims to address, seeking to uncover more about the complex architecture of the processes involved.

4. Results

Table 1 presents precise numerical data on the descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis) of the variables included in the SEM analysis. In this sample, none of the variables approach extreme criteria, thereby confirming the adequacy of the estimation and the fit of the proposed model.

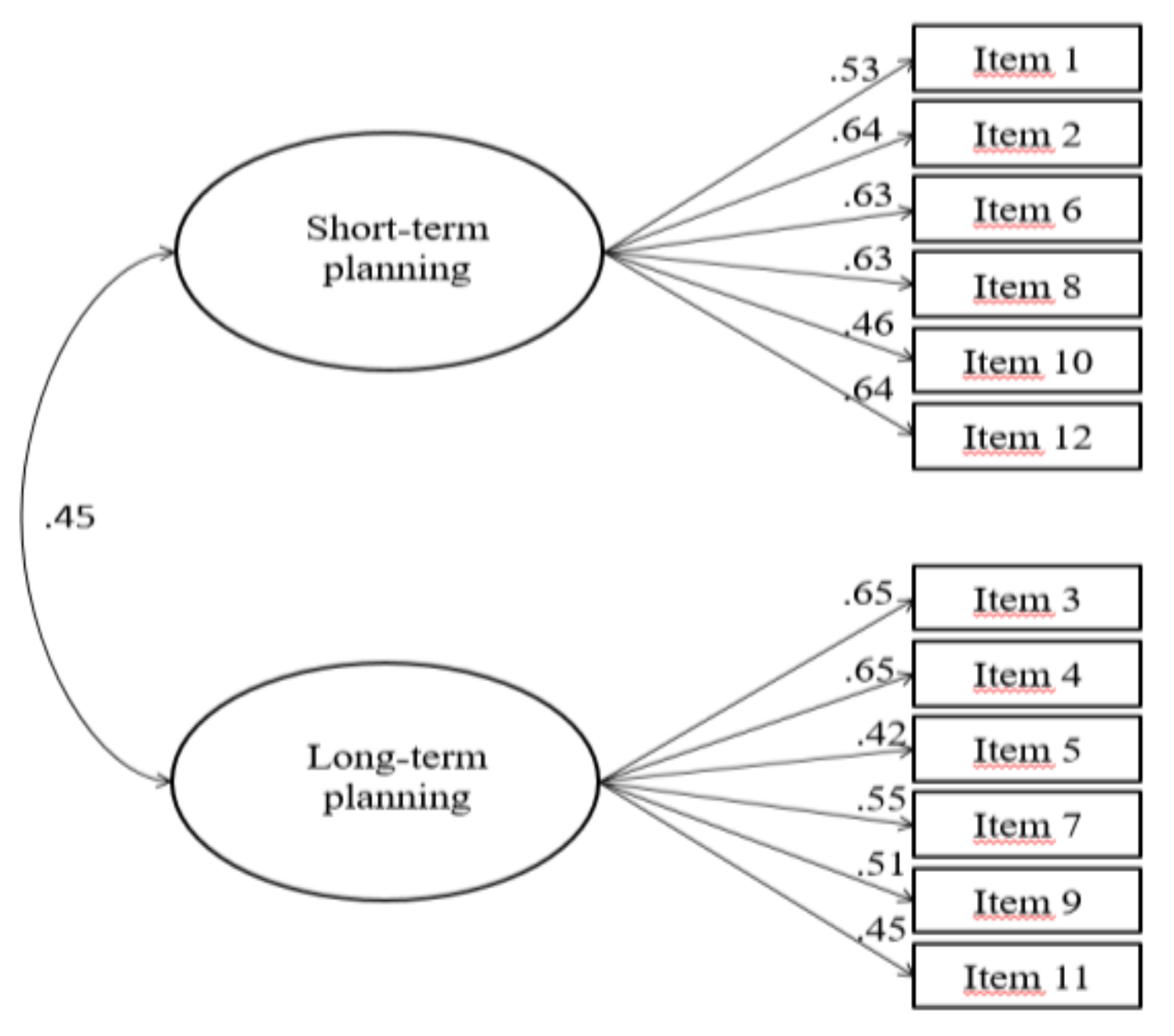

Regarding CFA, the TMPI exhibited optimal fit (GFI = .963; AGFI = .945; TLI = .942; Critical N = 342; CFI = .954; RMSEA = .044, 90% CI [.032, .056]) and acceptable factor loadings (see

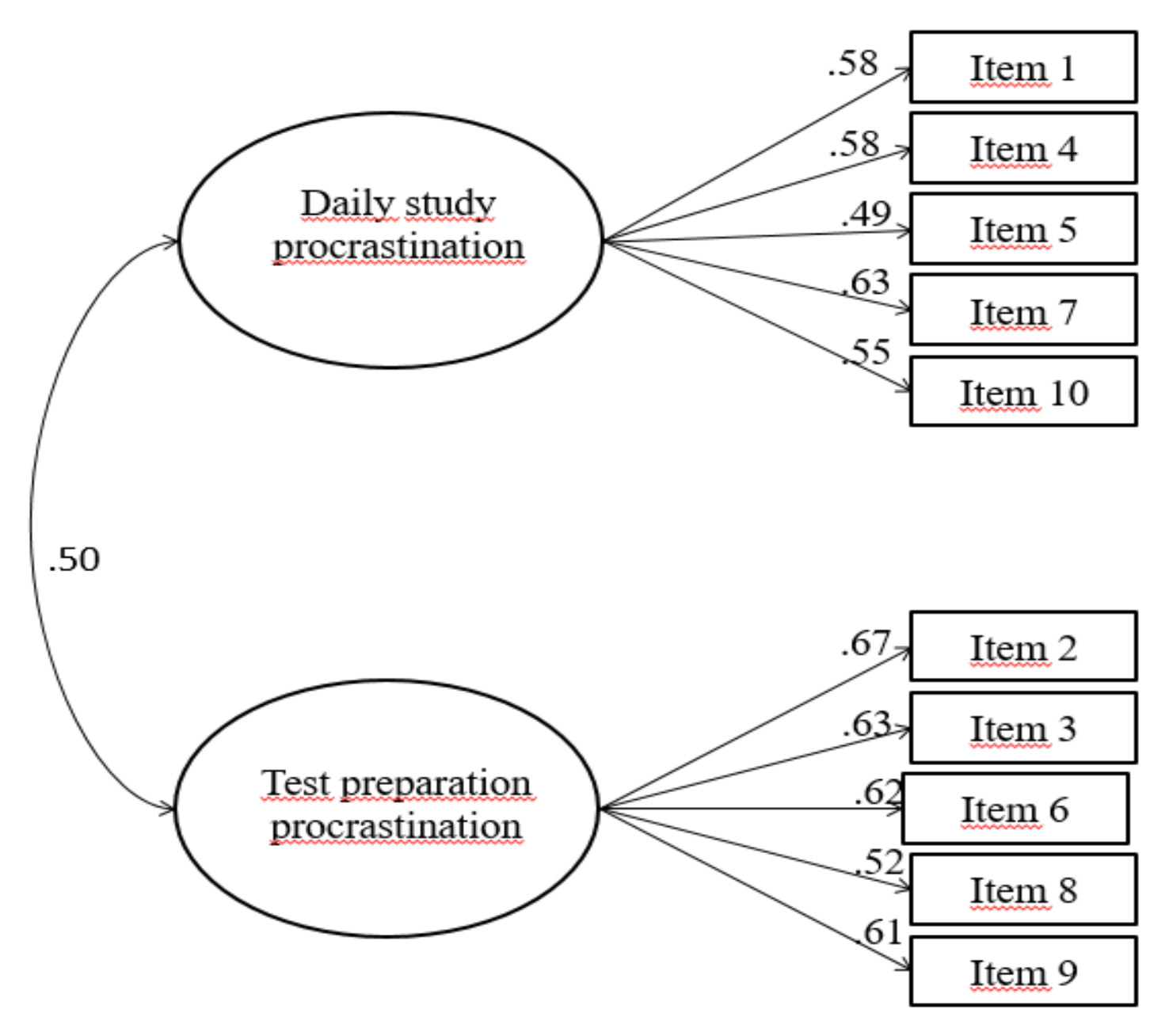

Figure 1). Additionally, reliability was acceptable for STP (α = .78; ω = .62) and LTP (α = .71; ω = .712). On the other hand, regarding SPQ, it demonstrated excellent fit (GFI = .985; AGFI = .975; TLI = .992; Critical N = 623; CFI = .994; RMSEA = .018, 90% CI [.000, .038]), higher than expected factor loadings (see

Figure 2), and acceptable reliability for both DSP (α = .71; ω = .703) and TPP (α = .74; ω = .748).

As a final step before SRA, an analysis was conducted to assess the strength and direction of linear relationships between quantitative variables (

Table 2). The interconnection between two variables manifests when a change in one results in a change in the other, measurable through Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient (r). Thus, considering the variables included in the model, it was found that all exhibit significant associations, except for the association between short-term planning and procrastination in the study for tests (r = -.049). Most associations range from very weak (|r| < .200) to weak (|r| = .200 to .399), with a notable moderate negative association between long-term planning and daily study procrastination (r = -.449). The results indicate a certain coherence among the analyzed variables.

Regarding the overall fit indices of the proposed SRA, the obtained values demonstrate robustness [χ²(243) = 429.557; p = .000; χ²/df = 1.768; GFI = 0.931; AGFI = 0.914; TLI = 0.916; CFI = 0.926; RMSEA = 0.039 (90% CI: 0.039-0.045); CN (.05/330; .01/350)]. These results confirm the hypothesis that the proposed model adequately represents the relationships between variables in the empirical matrix, thus validating its theoretical framework.

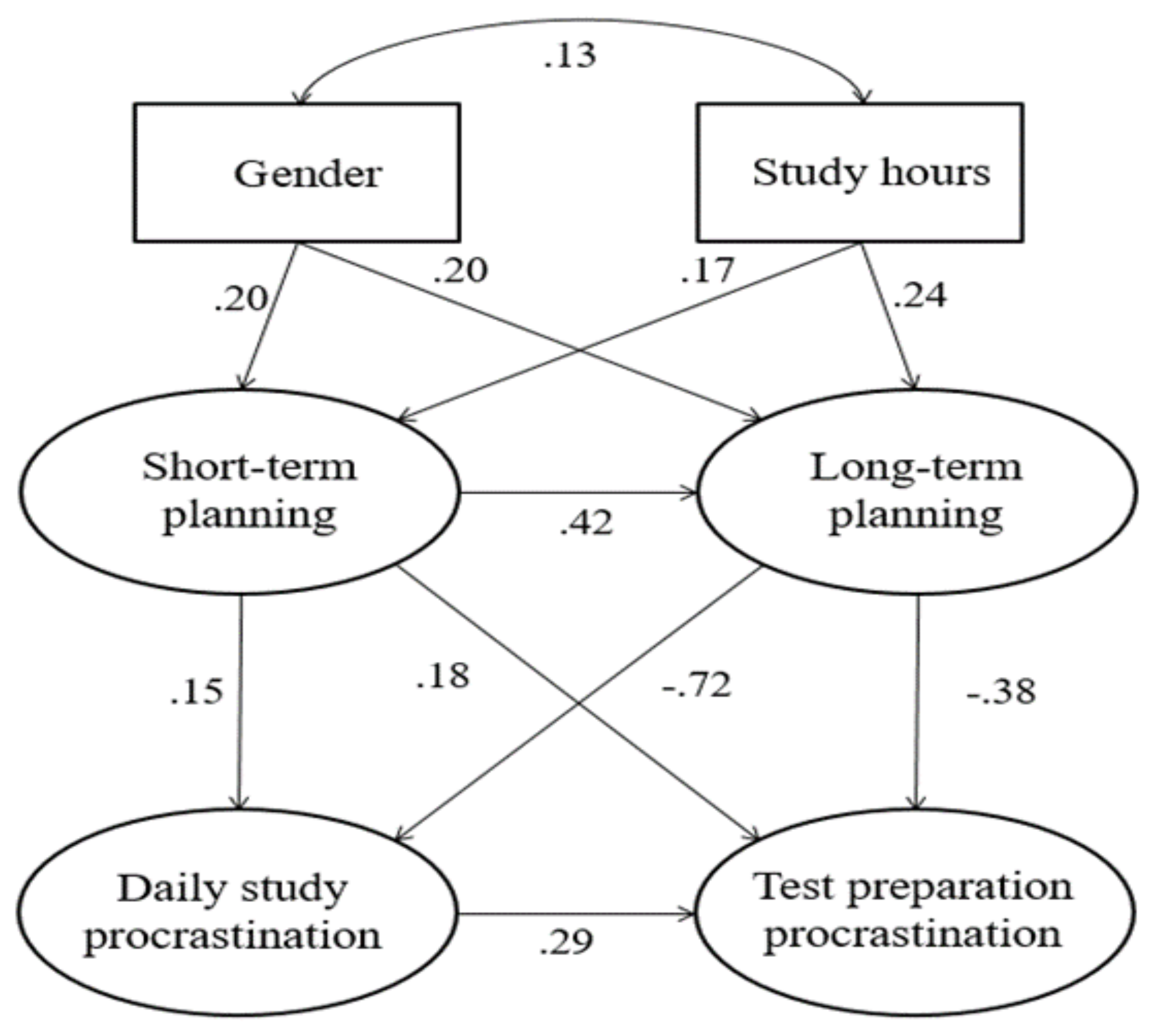

Based on the detailed analysis of

Figure 3, we can infer that the formulated hypotheses were validated, all demonstrating statistical significance. It is observed that girls exhibit a stronger tendency to plan their study time management in the short term (

β = .20;

p < .001) and in the long term (

β = .20;

p < .001) compared to boys. Regarding study hours, students who dedicate more time to studying show a greater tendency to plan their study time management in the short term (

β = .17;

p < .001) and in the long term (

β = .24;

p < .001).

In the domain of study time management planning, students who engage in short-term planning also tend to do so in the long term (β = .42; p < .001). However, those who focus their efforts on short-term study time planning tend to procrastinate more in daily study (β = .15; p < .05) and test preparation (β = .18; p < .05). In contrast, students who excel in long-term study time planning tend to procrastinate less in daily study (β = -.72; p < .001) and are also less likely to procrastinate in test preparation (β = -.38; p < .001). Finally, it is observed that students who procrastinate in daily study also show a tendency to procrastinate in test preparation (β = .29; p < .01). The analysis of covariance further suggests that female students have a greater number of study hours compared to male students (β = .13; p < .01).

Regarding the explained variances of the constructs, the squared multiple correlations (η²) reveal that short-term planning is explained by gender and study hours by about 8% (η² = 0.076), and long-term planning is explained by gender, study hours, and short-term planning by approximately 37% (η² = 0.366). Daily study procrastination is explained by gender, study hours, and short-term and long-term planning by about 43% (η² = 0.431). Long-term procrastination is explained by approximately 31% (η² = 0.307) by gender, study hours, short-term and long-term planning, and daily study procrastination. It is noteworthy that the proposed model demonstrates a fairly acceptable explanatory capacity.

5. Discussion

It is widely recognized that time management and the planning of study hours are essential pillars for sustainability in education, promoting a more effective, healthy, and balanced learning environment. The main objective of this study was to evaluate how the planning of time management, short-term and long-term, for students’ school activities impacts their PR behaviors in daily study and test preparation. Additionally, the study aimed to analyze how gender and the number of study hours spent by students over a seven-day week influence their organization of time management for school activities in the short and long term. The existing literature reveals significant gaps in attempts to relate these constructs, and research using SEM methodology is still scarce. Therefore, this study aims to expand the analysis of relationships between the study variables by using this analytical method, which simultaneously considers all direct and indirect effects. In this context, the study data corroborate the hypotheses proposed in the model when observing the relationships between the variables in question.

Thus, it is found that girls demonstrate greater time management planning for studying compared to boys, in the short and long term, presenting similar values, which confirms hypotheses H1 and H2. These findings are consistent with results obtained in previous studies [

15,

26], indicating that females exhibit more effective school time management. Some studies suggest that female students tend to have higher levels of intrinsic motivation and self-discipline [

13], as well as greater academic responsibility and conscientiousness [

6], compared to male students. These factors significantly influence how female students plan and manage their study time. Additionally, girls often use more structured and efficient study strategies, more inclined to employ study techniques that involve planning and review, enhancing time management and study effectiveness [

20].

Marcílio et al. [

18] contribute to this perspective, highlighting how adequate time planning is positively associated with students’ self-discipline and volitional control. The ability to anticipate the temporal demands of school activities and implement strategies to avoid PR are central elements supporting regulation. Understanding how gender influences study time management can assist educators and policymakers in developing more personalized and effective educational strategies tailored to the specific needs of boys and girls.

When considering study time, it is evident that students who invest more hours in this process also meticulously organize their time management, especially from a long-term perspective, thus confirming hypotheses H3 and H4. Similarly, Lourenço and Paiva [

15] reveals that students who dedicate many hours to studying need more thorough planning to balance various subjects and extracurricular activities. This requirement can propel them towards developing advanced organizational and planning skills.

Marcílio et al. [

18] emphasize that time management extends beyond the hours dedicated to studying, encompassing the quality and depth of engagement in school activities. Conscious planning enables students to focus on meeting deadlines and achieving a deep understanding of content, promoting more meaningful learning. In this context, Zimmerman [

58] explores how time management plays a crucial role in students’ academic performance, highlighting that studying can profoundly influence how students plan and organize their academic activities. Students who invest more time in studying can develop more effective and efficient study techniques, gaining the ability to identify optimal strategies for absorbing and retaining information. Additionally, they tend to maximize concentration and minimize fatigue, thereby enhancing their academic performance.

The studies mentioned generally demonstrate that effective time management is an essential skill that can be developed through practice and discipline. The time dedicated to studying enhances students’ academic knowledge and improves their planning, organization, and self-discipline skills, contributing to superior academic performance [

32].

The results indicate that students who plan short-term time management tend to maintain this practice in the long term, confirming hypothesis H5. Short-term time management establishes consistent behaviour that, becoming second nature, facilitates time management over longer periods. This observation is supported by Matta [

24], who emphasizes that short-term planning strengthens essential organizational skills, which can be expanded over time. Academically successful students develop solid study habits, manage time effectively, organize content, and strategically use learning resources. This approach creates a strong foundation for continued success.

Academic performance depends on effective planning, meeting deadlines, and good study habits. The continuous practice of short-term planning allows students to develop essential organizational skills that are easily applicable in the long term [

23]. By following appropriate methodologies, students develop satisfactory study practices characterized by efficient organization and meticulous learning planning [

15]. In summary, practicing short-term time management planning for school activities establishes a solid foundation of skills and habits that naturally expand into long-term planning, contributing to a more organized and successful academic journey.

Regarding hypotheses H6 and H7, the results confirm them: students who engage in short-term planning tend to procrastinate both in daily study and in test preparation. However, this latter relationship, although proposed, is the only one that is not statistically significant in the presented SEM model. Students who engage in short-term time management planning may tend to procrastinate in daily study and test preparation for various reasons, including perceived abundance of time, underestimation of tasks, and lack of intrinsic motivation. Several studies and authors have explored this phenomenon, providing insights into underlying causes and potential solutions [

5,

32,

33,

35].

Simultaneously, Fior et al. [

37] explore various reasons that can foster PR, such as poor time management for school tasks, unfavorable environments, difficulty concentrating, and anxiety about assessments. These feelings of tension and anxiety can paralyze students, leading them to procrastinate when faced with tests and assignments. Students who engage in short-term planning may feel they have enough time to complete their tasks later, prompting them to postpone the start of their studies. Lack of a detailed view of long-term tasks can lead to underestimating the time and effort needed to complete them, resulting in PR. Motivation plays a crucial role: students lacking intrinsic motivation tend to procrastinate due to a lack of interest or enthusiasm. Distractions and lack of self-discipline are also contributing factors, especially without a detailed plan [

32].

Regarding hypotheses H8 and H9, the results confirm that students who dedicate time to long-term planning of their academic activities show a lower tendency to procrastinate in daily study tasks and test preparation, aligning with other studies [

15,

31,

32]. The difference observed in the values of PR relationships between daily study (

β = -0.72) and test preparation (

β = -0.38) may be explained by various factors related to time management and the nature of school tasks, including routine and consistency; perception of urgency; task fragmentation; management of anxiety; immediate feedback; and self-regulation strategies.

Silva et al. [

28] mention that PR, often fueled by difficulty concentrating and a lack of a suitable study environment at home, leads to constant interruptions and task postponement. They also argue that this cycle of attentional dispersion undermines the necessary preparation to achieve learning goals. The absence of effective short-term and long-term planning exacerbates this situation, highlighting the need for a continuous effort to create favorable conditions for studying and maintaining a disciplined routine.

Studies emphasize the importance of short-term time management in reducing PR and enhancing study effectiveness [

29,

59]. They suggest that students with higher academic performance tend to set goals, estimate the time required for task completion, and maintain a meticulous study routine in the short and long term. Moreover, they regularly assess progress in the learning process, mitigating the impact of PR on their school activities.

On the other hand, Lourenço and Paiva [

15] point out the need to address PR through adaptive strategies that promote ongoing preparation and management of large-scale tasks, such as tests. These explanations illustrate that combining a well-established routine, perceiving tasks as more manageable, and implementing self-regulatory strategies can help understand why students procrastinate less in daily studying compared to test preparation.

Regarding hypothesis H10, it is confirmed that students who procrastinate in daily studying also tend to procrastinate in test preparation. In this study, students emphasize the importance of items highlighting inconsistency in daily studying and interruptions of academic activities to engage in leisure distractions. This observation aligns with Silva et al. [

5], who emphasize that PR manifests in various daily tasks and diverse contexts, particularly emphasizing the school context. Despite its potential drawbacks, this practice is often adopted by students.

These procrastinating behaviors occur more frequently when demands intensify and become more challenging [

36,

60]. The tendency to postpone crucial tasks compromises students’ ability to set clear goals, plan effectively, and maintain focus on academic activities. Mosquera et al. [

33] emphasize that this voluntary delay can harm academic performance, often linked to dysfunctional beliefs and thoughts such as fear of failure or a belief in one’s inability to complete a task.

Júnior et al. [

60] highlight that PR brings about several problems and negative consequences, both at an individual and collective level: reduced performance, increased stress, negative impacts on physical and mental health, and wastage of resources. This reality reinforces the perception that crucial factors to understand and address PR are linked to self-efficacy, which strongly influences students’ motivation, behaviour, and habits. Research also underscores the urgent need for effective intervention strategies, emphasizing the importance of raising awareness about PR [

37], providing tools for time management, and promoting more productive work habits [

18].

Limitations and Future Research

While this study presents interesting results and offers significant contributions, it is crucial to interpret the implications cautiously, considering certain limitations. The proposed model integrates theoretically relevant variables to explain the development of students’ short-term academic time management and academic PR. However, future research needs to expand the sample size and adopt a multilevel approach for a more comprehensive and precise understanding.

Additionally, all data were obtained through self-report questionnaires, which may not adequately capture real-time responses in the contexts of teaching and learning processes. Therefore, future studies should deeply investigate the processes that lead students to procrastinate in their various school activities, using qualitative methodologies such as interviews or focus groups. This approach would allow for a more precise examination of students with histories of consistent success over time and those with repeated failures, enabling comparison of any significant differences. It would also help identify PR behaviors and trends associated with each gender, enabling the implementation of targeted interventions to assist students in improving study efficiency and reducing PR behaviors.

The results show that the model reveals unexplained variance in students’ academic PR, suggesting the possible existence of other crucial predictor variables that should be included in future research. Although this study was conducted with a substantial sample (n = 506), its findings are not intended to be generalized to the entire student population at this educational level. The aim is to contribute to a deeper understanding of the implications of the analyzed constructs across different school years and, above all, to stimulate further research on this highly relevant topic.

6. Conclusions

In attempting to address the questions posed in the introduction, it is imperative to affirm that schools have, and should continue to have, a crucial role in promoting the educational quality of their students, responding to Goal 4. Understanding in depth the elements that influence and shape the learning process is essential for achieving academic mastery. In this context, effective time management, meticulous planning of study hours, and understanding the underlying reasons for academic PR emerge as fundamental pillars. These elements are crucial for achieving Goal 4 “Quality Education: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” at all levels of education, thereby promoting quality education [

3,

8]. This approach allows building an education system that meets students’ immediate needs and prepares them holistically for future challenges.

Upon examining the theoretical rationale developed in recent years, there is an urgent need to explore the predictor variables of students’ academic PR. Students’ effectiveness in time management proves to be fundamental, and crucial in mitigating procrastinator behaviors and optimizing academic performance. Several studies underscore the vital importance of temporal planning for educational success [

18,

29,

59]. Thus, the relationship between academic time management planning and PR is evident in the referenced studies. A conscious and strategic approach to time management reduces PR and strengthens students’ ability to actively direct their learning process.

In the theoretical context of academic PR, the difference between successful students and those facing academic difficulties lies in how they plan and manage time dedicated to school activities and their propensity to postpone tasks. Due to its negative nature, some research indicates contrasting effects, often linking it to harmful practices capable of initiating a dangerous cycle with potential consequences, including low academic performance, feelings of guilt, lack of motivation, anxiety, and even depression.

Research on time management in school activities and students’ dedication to daily study and test preparation is vital for sustainability in education for multiple reasons. Firstly, it contributes to optimizing learning, allowing for more effective use of available time. Moreover, it promotes the development of time management skills, crucial not only for the academic journey but also for future life. Reducing stress and PR is another significant benefit, providing a healthier and more balanced study environment. This practice also fosters students’ autonomy and responsibility, empowering them to manage their study routines efficiently. Improved academic performance naturally follows from this planning and achieving a balance between study and leisure, which is crucial for overall student well-being. Adequate preparation for assessment situations is another central aspect, ensuring students feel confident and well-prepared.

Finally, study time and how students plan and manage that time, aiming to mitigate successive PR behaviors in school activities, are essential pillars for sustainable and quality education. The harmonious combination of time management and academic discipline promotes an environment conducive to students’ holistic development, reflecting academic success and the building of vital life skills.