1. Introduction

The importance of contact with nature for human health was the subject of numerous research. Numerous studies confirmed that exposure to natural environments, and urban green and blues spaces can reduce stress [

1,

2,

3,

4], improve attention recovery [

4,

5], promote mental restoration, and increase happiness [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Nevertheless, rapid urbanization leads to a decrease in open green space accessibility within urbanized areas. The results are severe, especially for the frail, poor, elderly and children. Morbidity is related to access to urban green spaces [

11]. The prevalence of asthma episodes is lower in places with abundant tree cover [

12]. There are attempts to promote urban planning and design for health, both in physical, mental, and spiritual areas [

13,

14,

15]. The spiritual needs are as important as physical demands [

13,

14,

15].

Hospitals provide care for the frail and ailing. We know that it is important to give contact with greenery to all: patients, staff members, and visitors. There is a vast literature about the design of healing and therapeutic gardens based on Evidence-Based Design [

16,

17,

18,

19]. There is research evidence confirming the need for “naturalness” [

4,

5,

6,

10,

20,

21] The importance of a view through a hospital window for patient recovery was proven by Roger Ulrich [

22]. Maggie Keswick Jencks wrote about the longing the patients have for beautiful, uplifting environments [

23]. The study conducted in The Leichtag Family Healing Garden at Children’s Hospital and Health Center, San Diego concluded with recommendations for including more trees and greenery, and more interactive ‘things for kids to do’ [

24]. There is still not much information about the preferred design of hospital grounds. Thus, the interesting question is what are the patients' preferences of patients when it comes to specific landscape architecture solutions and individual design? This study aims to fill the gap in knowledge and understanding. The objective is to provide designers with information about the preferences of prospective patients.

Study Aims

This study focuses on the perception and preferences of prospective patients regarding the landscape design of hospitals.

This study aims to fill the research gaps and achieve the following objectives:

Investigate what patients want when it comes to hospital settings

Analyze what people expect of the hospital landscape.

Evaluate the preferences for various types of landscape design on hospital grounds.

2. Materials and Methods

The method of online survey was employed.

The distributed questionnaires contained a clear statement emphasizing the confidentiality and privacy of all collected information and data. No personal identifiers, such as names, were recorded in the questionnaires. The responders could abandon the questionnaire filling at any time. The survey included 38 questions and was designed to require less than 15 minutes to fill. The questions included only basic demographic information about sex and age.

The questionnaire was divided into basic questions regarding attitude towards contact with nature, and the importance of the design of the healthcare environment. The second part of the survey included questions regarding aesthetic preferences for landscape design. It was based on photographs of various gardens (

Figure 1). Firstly, the individual gardens' suitability for the hospital site was assessed and then the respondents chose their favorite one (

Figure 1A-F)(

Figure 2A-F).

Then, the respondents choose their favorite path design (

Figure 3A-H).

The following questions concerned preferences for various types of landscape – natural or designed (

Figure 4).

The survey included questions examining preferences for garden composition (

Figure 5), interior type (

Figure 6), preferred parterre – lawn or flowers (

Figure 7), size of garden interiors (

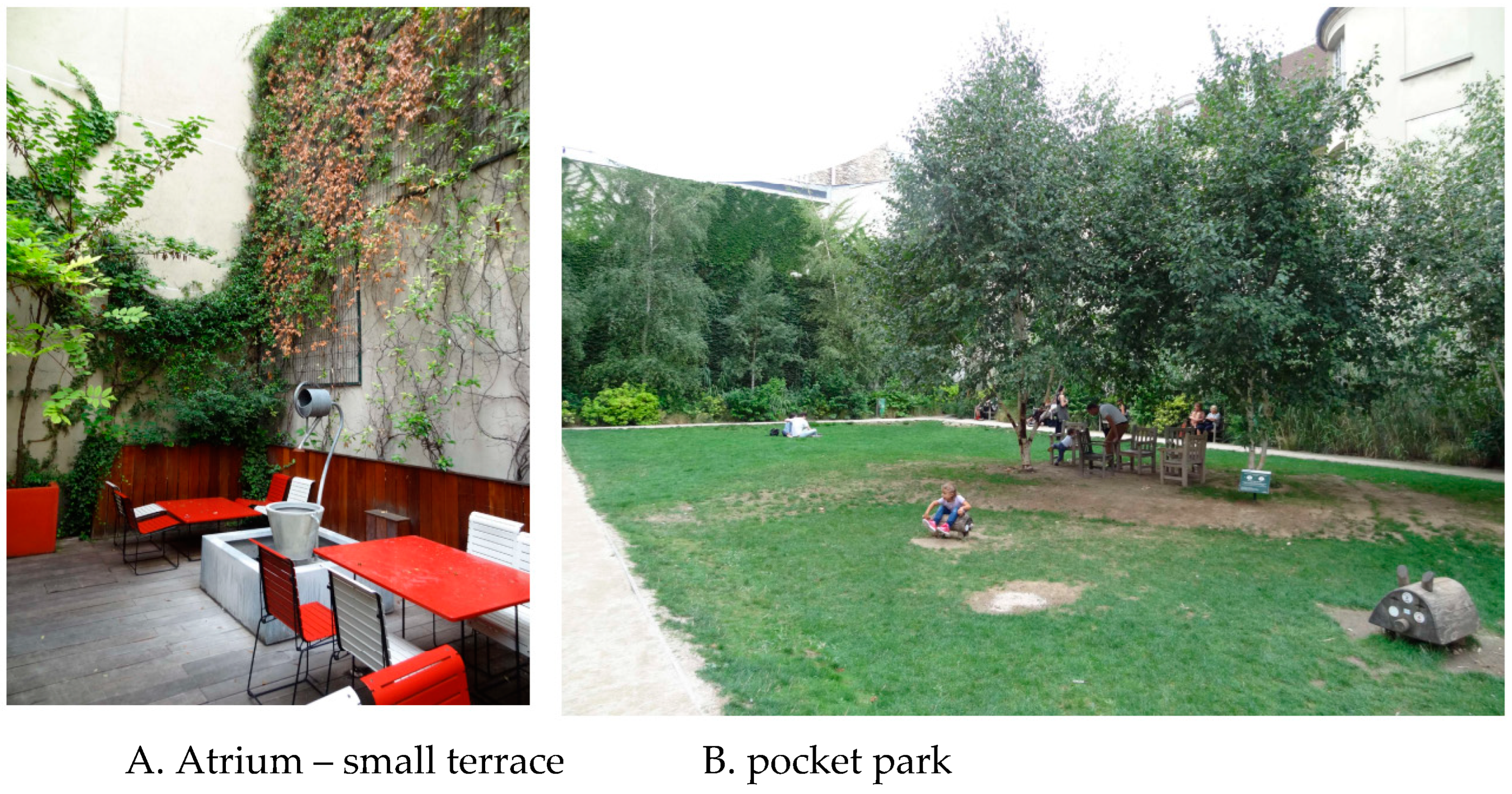

Figure 8), atrium type (

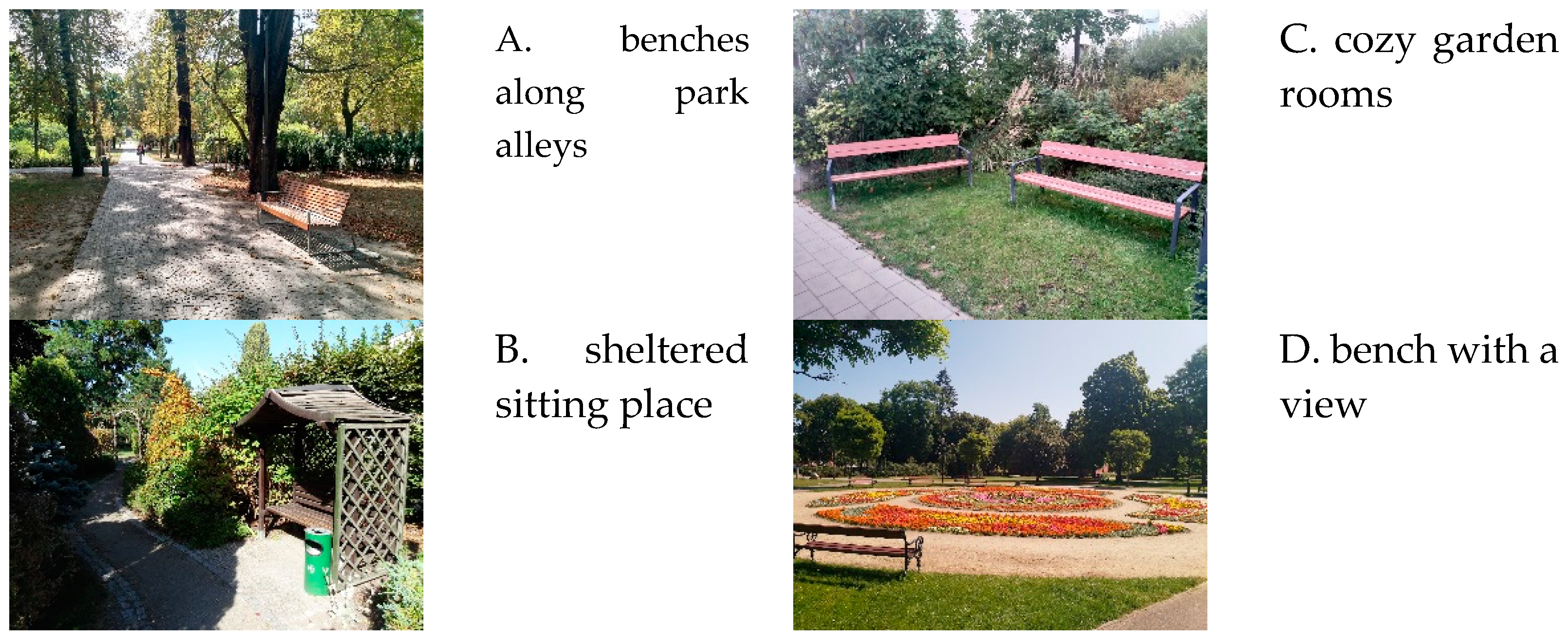

Figure 9), and sitting arrangements (

Figure 10).

The savannah hypothesis links human preferences to savanna-like settings - the grasslands of East Africa [

6,

26]. The survival advantages of the savannah landscape lead to the desire for reproduction in other parts of the world. Therefore the question for preferred parterre was added (

Figure 6).

There is a preference among human beings toward landscapes with water [

25]. Therefore one of the questions concerned the presence of water (

Figure 7).

One of the questions concerned the size of garden interiors (

Figure 8) and atriums (

Figure 9).

One of the questions concerned the preferred location and setting for benches and sitting places (

Figure 10).

The rest of the questionnaire included questions regarding the relationship between self-assessed well-being and hospital site design. It included the list of adjectives describing the feelings associated with hospital environments, as they are and as they should be according to respondents. The questionnaire used in the study is inspired by the ACL Adjective List and refers to opinions about the external space of healthcare facilities. However, unlike the original test by H. G. Gough and A. B. Heilbrun, it is neither such a comprehensive tool nor does it have separate scales used to distinguish individual human properties (self-image, needs, originality, intelligence, etc.)[

27].

However, according to the possibilities of using ACL, the subject of the study may be not only personality traits, but also objects, such as cities, their parts, or specific buildings. The actual tool was originally designed to assess personality from an observer's perspective. It was then extended to include self-report regarding the real self and the ideal self, also indicating applications such as relating aspects from the past to the present [

28,

29]. Such research properties - enabling the comparison of actual (present) and expected (future) features, served as a source of inspiration to develop a simplified list of terms referring to the current and desired state of the space surrounding medical facilities.

The terms provided to the respondents concerned two situations. In the first case, the respondents were asked to indicate terms referring to the space surrounding the facility where they receive treatment - as they currently perceive it (real image). In the second step, they should choose the properties of this space as they would like it to be (expected image). In each situation, the subjects selected the corresponding terms from the same range of 36 adjectives. This list contained 12 pairs of features (24 items) selected based on the opposition (e.g., soothing - causing anxiety, eye-catching - not attracting attention, orderly - chaotic, monotonous - varied, sad - joyful, etc.) and 11 terms referring to to the function of the space and meeting the needs of its users. The adjectives were identified by the authors of the article as important and worth measuring because they refer to the emotional sphere of the users of the analyzed spaces and are therefore an aspect that is difficult to measure in a way other than the self-report method. In addition, they indicate whether or not needs are met, such as a sense of security, relief, comfort, or promoting regeneration.

The survey asked for recommendations on what types of recreational infrastructure should be available on the hospital site, and whether it should be open to all visitors. An open question for suggestions was included. The respondents could also share their opinions about the importance of viewing a tree through hospital windows and the availability of interior winter gardens.

Study Organisation

This study received formal consent from the University of Gdańsk Ethical Commission in April 2024. The survey was conducted from 4th May to 8th July 2024. The online questionnaire was distributed using e-mails and social media with electronic links and QR codes. E-mails were sent to the university Students, Teachers, and administrative staff from the University of Gdańsk, and Lodz University of Technology, as well as other Universities in Poland. Moreover, social media – Facebook and LinkedIn were also used to distribute the questionnaire among other internet users, not only Academia. The questionnaire was in Polish language. The objective was to include all age groups of adults, except for minors under 18 years of age.

Participants

The final research sample consisted of 103 respondents who filled out the anonymous questionnaire. The majority of respondents were women 85 (82,5%), 18 were male (17,5 %).

The survey was addressed to adults, therefore there were no respondents younger than 18 years old. As shown in

Table 1, 85 respondents were female (82,5%), and 18 were male (17,5 %). 46 respondents were 18 to 25 years old, 19 were 26 to 40 years old, 33 were 41 to 60 years old, and 4 were 60 years and older. Hence, most of the respondents were women in the age range of 18 to 25 years and presumably students.

3. Results

The results confirmed the importance of contact with nature for the patients (92 out of 103 = 89,3%). Only 11 persons were undecided (10,7 %). No one answered that contact with nature has no importance to them.

35,3% of respondents seek restoration in contact with nature every day, 44,1% once a week, 18,6% once a month, and 2% once a year.

The vast majority 96,1% declared that the surroundings of the healthcare building influence the health and well-being of patients. 3 persons were undecided, and 1 person marked no. The majority 85,4% understand that the hospital environment influences the quality of work of health personnel. 12,6% declared having no opinion, and 1,9% (2 people) thought it does not influence at all. When it comes to visitors -members of the patient’s family, 89,3% marked that the hospital site design influences visitors' health and well-being, 4,9% had no opinion and 5,8% (6 respondents) declared it has no influence.

The results of the survey with photographic experimental images are presented in

Table 2. The selection of experimental images - Various garden types, selection 1.

(

Figure 1) proved preference for B Ordered composition with formed topiary(53,5%)., C. modern garden with grasses (47,5%), and D. Modern colorful garden (39,4%). The selection of experimental images - Various garden types, selection 2.

(

Figure 2) demonstrated an inclination towards B. The paths in the park, as it was marked as the most preferred option by 73 respondents (72,3%). A. Flower parterres were the second most popular option marked by over half of respondents 58 (57,4%).

Among the options for various alleys, the favorites were (Figure - H. The wooden platforms (45,1%), B. sandy alleys (44,1%), and F. paths with elastic, shock-absorbing surfaces (44,1%). They were preferred over other solutions.

Preferred landscape (

Figure 4). The preferences for natural and designed landscapes were almost half to half -51% and 49%.

Preferred garden composition (

Figure 5). The majority of respondents preferred A. calm garden composition 68,6 %. B. Multi-colored composition, kitchen garden was chosen by 43, 42,2% of respondents, D. Flower parterre by 34, 33,3% and C. Spontaneous community garden only by 8,8%, 9 responders.

Preferred parterre (

Figure 6). Flower parterre was preferred over lawn – 78 to 24.

Preferred interior type (

Figure 7) Water pond was preferred over lawn – 76 to 25.

Preferred size of interiors (

Figure 8) The responders demonstrated a preference for B. smaller interiors (46,5%) than A. large ones (13,9%), C. small garden rooms (32,7%) or D. Small walled garden rooms (6,9%).

When it comes to atrium type (

Figure 9) the pocket park (78,2%) was preferred over a small terrace (21,8%).

The preferred location for sitting benches (

Figure 10) was B. Sheltered sitting place (63,4%), followed by A. Benches along park alleys (51,5%) and D. Benches with a view (48,5%) over C. Cozy garden rooms (32,7%).

The majority of responders find the environments of the place where they stay important, e.g., concerning the view through a window. It is of utmost importance for 48,5%, very important for 36,6%, and important for 9,9%.

The responders declared that the view through the window of the healthcare facility on greenery influences their well-being. On a scale of 1-5, 62% declared 5 (utmost importance), 32% declared 4 (very important) and 5% declared 3 (important).

When it comes to a room with a window overlooking the activity of other people the opinions were more nuanced. On a scale of 1-5, 36,1% declared it was of utmost importance to see the activity of other people, 36,1% marked it was very important, and 24,7% marked it important.

The open question about the functions of the terrain adjacent to the hospital brought 71 answers. The majority of respondents wrote about the need for calm and tranquil open green spaces and healing gardens away from the hustle and bustle of everyday life and buffered from traffic. One of the respondents draws attention to missing sheltered benches in case of bad weather. Another wrote about the need for recreation and sports equipment or hobbies. Mini playgrounds for children were also mentioned along with small ponds, fountains, or other water features. Small café and brine graduation towers were also mentioned by various respondents. Uplifting, colorful gardens accessible on wheelchairs and trolleys were mentioned repetitively by many respondents. The hospital grounds were mentioned as a space to sit in quiet, relax, and spend quality time with visiting relatives and friends.

The adjectival method used provides information on the perception of the actual and expected appearance of the immediate surroundings of medical facilities based on responses collected from 103 study participants. The results provided in the text have been rounded to whole numbers.

The answers regarding the current development of space constituting the immediate surroundings of healthcare facilities are varied but indicate that they are perceived by the respondents primarily as neutral (40% of responses) monotonous (41%), and then as sad (36%), and not paying attention (34%). Users also indicated that these places were not conducive to regeneration (29%), or even generated a feeling of depression (27%). The fewest respondents described the current development of spaces surrounding healthcare facilities as fascinating and eye-catching (7%) or as hiding the sentimental aspect of places with a fascinating history (2%). For the people participating in the study, these zones are not very diverse - with a small richness of species and poorly contrasted, therefore they do not function as a positive distractor that allows you to break away from problems for a while. The results obtained, however, do not indicate a complete lack of positive implementations in this area, because some respondents perceive the environment of medical facilities as clearly positive - providing relief (12%) and hope (9%), optimistic (10%), joyful (8%), giving a sense of security (11%) or promoting regeneration (8%).

The answers regarding the expected development of the space constituting the immediate surroundings of healthcare facilities are highly dispersed. However, based on the answers provided by over half of the respondents, it is possible to indicate the properties of places with this function preferred by users. These include: spaces that provide relief (79% of study participants), promote regeneration (65%), are joyful (63%), give hope (58%), allow you to feel comfortable (60%), and at the same time allow you to break away from problems (55%) and generating optimism (51%). The respondents expect well-ordered places (50%) which are peaceful (48%).

4. Discussion

The majority of respondents were young women under 25, but other age groups were also represented. Male respondents constituted a minority, with only 18 respondents. The respondents know the importance and benefits of contact with nature for their health and well-being. They seek refuge and respite in contact with nature on a daily or weekly basis (79,4%).

The majority of respondents confirm that the surroundings and site design influence the health and well-being of people using a building (97%). Thus, they are well aware of the influence the hospital ground design has on patients, staff members, and visitors (85,4% to 96,1%).

The results of this study with experimental images confirm the preference for a calm, colorful garden with various plants. The permeable alleys, comfortable for strolling regardless of mobility, were chosen over concrete paving. The respondents preferred flowers and water features over plain lawns. The smaller interiors were preferred over larger or tiny ones. The pocket park was chosen as a favorite type of interior by the majority of respondents.

The study shows that the immediate surroundings of medical facilities should exclude the impression of fear, depression, sadness, pessimism, or anxiety. At the same time, the fewest people used terms to describe the unfavorable appearance of such places, such as: chaotic (2%), monotonous (2%), not attracting attention (4%), one-colored (3%), or uniform (4%). Half of the respondents would expect these places to be arranged in an orderly manner (50%), which is consistent with the results of aesthetic preferences for the surroundings of healthcare facilities (indicating a community garden and a kitchen garden as one of the least appropriate, among others, due to their strong diverse character, susceptible to constant modifications or for fear of neglect, and the dominant preference for a classic composition with formed plants). In their preferences, respondents indicated multicolor (46%) and variety of species (32%), a sunnier space (42%) than a shaded one (24%), with a clear separation of the garden zone (44%), and a meeting place (41%). The feature defined as "wildness of nature unchanged by humans" was indicated by 22% of the surveyed people, which, combined with the dominant visual feature of "order" (50%) and a slight predominance of preferences for natural landscape over the composed landscape (study on aesthetic preferences, with experimental photographic images) may suggest the priority of forms giving the impression of nature devoid of human interference, but with a composed intentional arrangement. The answers to open questions confirmed the results of the adjectival method research.

The respondents confirmed that they regard the view of trees through a hospital window as the most important (76,5%), more than natural landscape (72,5%), peaceful garden (59,8%), or popular public park (23,5%). 6,9% of respondents declared preference for the view of the playground or sports field, and 7,8% would like to see public space. Only 2 respondents (2%) would like to see the busy road through the hospital window.

The importance of a view of trees was declared on a scale from 1 (unimportant) to 5 (utmost importance) – 58,8% declared 5 (utmost importance), 30,4% marked 4 (very important), and 7,8% responded 3 (important).

The respondents confirmed the need for a winter garden with controlled microclimate.

85% of respondents think that the strolling paths are a necessary feature of a hospital site. 62% would like a place to sit and rest in peace. Around half of the respondents would like to see on a terrain belonging to healthcare building the following features: a roofed shelter, flower meadow, natural forest, water feature, a place to sit in the sunshine, and a feeder for birds. 42% declared preferences for flower beds. 35% chose a sensory garden and 26% - a sensory path. The spiritual needs are also important. 32% of respondents would like a chapel next to the hospital or healthcare units. 15% would like a memorial garden, 9% a Biblical garden, and 6% a Rosary path. The hospital room should overlook a peaceful healing garden with numerous sheltered benches and strolling paths.

Limitations

This study was limited to a relatively small research sample from Poland. The majority of respondents were young women under 25. Relatively few males took part in the survey. Whether females are more sensitive to the qualities of surroundings and contact with nature requires further study.

5. Conclusions

The study confirmed that patients know the importance of contact with nature and expect the hospital site to provide a place of refuge and respite with calm garden compositions, stimulating physical and mental recovery. Trees, flowers, and water features are as important as accessible paths for strolling and numerous sheltered benches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T. and J.M.; methodology, M.T. and J.M; validation, M.T. and J.M; formal analysis, M.T. and J.M; investigation, M.T. and J.M; writing—original draft preparation, M.T. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, M.T. and J.M; visualization, M.T. and J.M; supervision, M.T. and J.M.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Opinion of the Research Ethics Committee

12/2024/WNS, 25 April 2024, University of Gdansk.

References

- Beil, K.; Hanes, D. The influence of urban natural and built environments on physiological and psychological measures of stress—A pilot study. International journal of environmental research and public health 2013, 10, 1250–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Chang, C.-Y.; Sullivan, W.C. A dose of nature: Tree cover, stress reduction, and gender differences. Landscape and 867 Urban Planning 2014, 132, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H. Beyond toxicity: Human health and the natural environment. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2001, 20, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The experience of nature: A psychological perspective; Cambridge university press: 1989. 893 19. Sullivan, W.C.; Kaplan, R. Nature! Small steps that can make a big difference. 2016, 9, 6–10 894 20. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.L. , Foley R., Houghton F. et al. “From therapeutic landscapes to healthy spaces, places and practices: A scoping review” Social Science & Medicine. Dec2018, Vol. 196, pp.123-130. 8p. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Biophilia, B. Natural Landscapes. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Kellert, SE, Wilson, E., Eds 1993, 73-137. 895 21.

- Van Herzele, A.; De Vries, S.J.P. ; Linking green space to health: A comparative study of two urban neighbourhoods in Ghent, Belgium. 2012, 34, 171–193.

- Carrus, G.; Scopelliti, M.; Lafortezza, R.; Colangelo, G.; Ferrini, F.; Salbitano, F.; Agrimi, M.; Portoghesi, L.; Semenzato, P.; Sanesi, G. Go greener, feel better? The positive effects of biodiversity on the well-being of individuals visiting urban and peri-urban green areas. Landscape and Urban Planning 2015, 134, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Hammitt, W.E.; Chen, P.-K.; Machnik, L.; Su, W.-C. Psychophysiological responses and restorative values of natural environments in Taiwan. Landscape and Urban Planning 2008, 85, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.C.; Irvine, K.N.; Bicknell, J.E.; Hayes, W.M.; Fernandes, D.; Mistry, J.; Davies, Z.G. Perceived biodiversity, sound, naturalness and safety enhance the restorative quality and wellbeing benefits of green and blue space in a neotropical city. Science 901 of The Total Environment 2021, 755, 143095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A. Morbidity is related to a Green living environment. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009, 63, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovasi, G. S.; Quinn, J. W.; Neckerman, K. M.; Perzanowski, M. S.; Rundle, A. J: Children living in areas with more street trees have lower prevalence of asthma, W, 2008; 62.

- Trojanowska, M. 2017 Parki i ogrody terapeutyczne.

- Trojanowska, M. Biblical Gardens and the Resilience of Cultural Landscapes—A Case Study of Gdańsk, Poland. Land 2023, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojanowska, M. . Assessment of sustainability and health promotion of three public parks in Poland’s Pomerania Region. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series, 21 June 2024; 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Marcus, C. , Sachs N.(2014) Therapeutic Landscapes. An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces.John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Gerlach-Springss, N. , Kaufman R.E, Warner S.B. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Winterbotton D, Wagenfeld A. 2015 Therapeutic Gardens. Design for healing spaces.

- Zhu, Liheng & Shah, Sarah. (2024). History and Evolution of the Healing Gardens: Investigating the Building-Nature Relationship in the Healthcare Setting. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health. 6. 100450. 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2024.100450.

- Ode, A.; Fry, G.; Tveit, M.S.; Messager, P.; Miller, D. Indicators of perceived naturalness as drivers of landscape preference. J 896 Environ Manage 2009, 90, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knez, I.; Sang, Å.; Gunnarsson, B.; Hedblom, M. Wellbeing in Urban Greenery: The Role of Naturalness and Place Identity. 903 Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, RS. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science. 1984 Apr 27;224(4647):420-1. [CrossRef]

- Keswick-Jencks, M. 1995 A view from the front line, available online: https://www.maggies.org/media/filer_public/59/89/5989b1c0-5ba4-4473-8c29-07a2f591f148/a-view-from-the-front-line.pdf, retrieved on 5.07. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, S. , Varni, J. W., Seid, M., Cooper-Marcus, C., Ensberg, M. J., Jacobs, J. R., & Mehlenbeck, R. S. (2001). Evaluating a children's hospital garden environment: Utilization and consumer satisfaction. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(3), 301–314. [CrossRef]

- Völker, S. , Kistemann T. “The impact of blue space on human health and well-being – Salutogenic health effects of inland surface waters: A review”. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2011 Nov;214(6):449-60. [CrossRef]

- Falk, John. (2020). Landscape Preferences. Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science (pp. 1-8). [CrossRef]

- Martowska K, Matczak A., Wrocławska-Warchala E., Możliwości interpretacji czynnikowej wyników badania Listą Przymiotnikową ACL, Przegląd Psychologiczny, t. 58, Nr 2/2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283503395_Mozliwosci_interpretacji_czynnikowej_wynikow_badania_Lista_Przymiotnikowa_ACL_The_possibilities_of_factor-based_interpretation_of_the_results_of_research_using_the_Adjective_Check_List (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- ACL Manual. Available online: https://www.practest.com.pl/sklep/test/ACL (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Martowska K, Matczak A., Wrocławska-Warchala E., Możliwości interpretacji czynnikowej wyników badania Listą Przymiotnikową ACL, Przegląd Psychologiczny, t. 58, Nr 2/2015; Available online:. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283503395_Mozliwosci_interpretacji_czynnikowej_wynikow_badania_Lista_Przymiotnikowa_ACL_The_possibilities_of_factor-based_interpretation_of_the_results_of_research_using_the_Adjective_Check_List (accessed on 7 July 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).