1. Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a genetic X-linked neurodevelopment disorder associated with the single monogenic mutation in methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) in up to 95% of cases [

1], more rarely by mutations in cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 (CDKL5) [

2], and forkhead box protein G1 (FOXG1) gene [

3]. The typical RTT clinical symptoms include early neurological regression in 80% of patients, afterward loss of acquired cognitive, social, and motor skills in a typical four-stage neurological regression. Since many of the core symptoms and neurological features can be shared with other neurodevelopmental pathologies, it is likely that the disorders share some critical molecular underpinnings [

4]. The coexistence of a perturbation of the immune system in RTT patients has been previously hypothesized [

5]. Moreover, the growing number of genome-wide association studies and incomplete concordance for autoimmune diseases in monozygotic twins concur to support the role of the environmental factors (including infectious agents and chemicals) in the breakdown of tolerance leading to autoimmunity through different mechanisms [

17]. In particular, a derangement of microglia immune responsiveness might be likely to occur in these patients, as neuroinflammation is a powerful modulator of the CNS immune system [

6]. Actually, the nexus between MeCP2 and autoimmunity has been reported in the literature [

5,

7,

8], and in particular autoantibodies to brain proteins i.e. nerve growth factor [

9,

10] and folate receptor [

11].

In pathological conditions of the central nervous system, such as RTT and other neurological diseases (e.g., multiple sclerosis, MS) in which antibodies and/or antigens involved in the disease are unknown, specific antibody detection in biological fluids is a challenge. In this context, we previously demonstrated that anti-N-glucosylated peptide CSF114(Glc) antibodies in a multiple sclerosis (MS) patient subpopulation [

12,

13,

14], preferentially recognize the hyperglucosylated adhesin protein of non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) and in particular the C-terminal portion HMW1(1205-1526), termed HMW1ct(Glc) [

15]. To the best of our knowledge, it was the first example of an N-glucosylated bacterial antigen that can be considered a relevant candidate for triggering pathogenic antibodies in MS [

15]. To be note that, after the introduction of the H. influenzae vaccine conjugate, the majority of invasive infections is now caused by NTHi in all age groups in the US [

16]. Since the NTHi cell-surface adhesins are heavily glucosylated on a relevant number of sequons exposed on beta-turns, the N-glucosylated residues are likely to be exposed conceptually in vivo in a multivalent shape, thus potentially generating an immunological response [

14,

17]. Translating these considerations to RTT syndrome, since MeCP2 acts intrinsically upon immune activation affecting neuroimmune homeostasis by regulating the pro-inflammatory/anti-inflammatory balance [

8], the hypothesis that environmental factors like bacterial infections could be involved in RTT is gaining interest.

With all these considerations in mind, we have previously used chemically modified β-turn peptide structures bearing an N-glucosylation to expose on the solid surface of the ELISA, to characterize specific antibodies in RTT patients' serum [

18]. In particular, RTT patients presented high antibody levels against N-glucopeptide CSF114(Glc), thus suggesting an alteration of protein N-glucosylation rate and the possible activation of autoimmunity processes in the syndrome [

19]. A dysregulated N glycosylation pattern in RTT pathogenesis was confirmed by a study on MeCP2-null mice, in which a reduced N-glycosylation in the protein involved in neuronal cell communication brain nucleotide pyrophosphatase-5, was characterized in both pre-symptomatic and symptomatic mice. Importantly, these N-glycosylation modifications were rescued by MeCP2 reactivation [

20]. The underlying principle for this chemical modification stems in N-glucosylation recognition can be a pervasive feature of biomolecules occurring in the central nervous system (CNS) pathologies characterized by neuronal disruption.

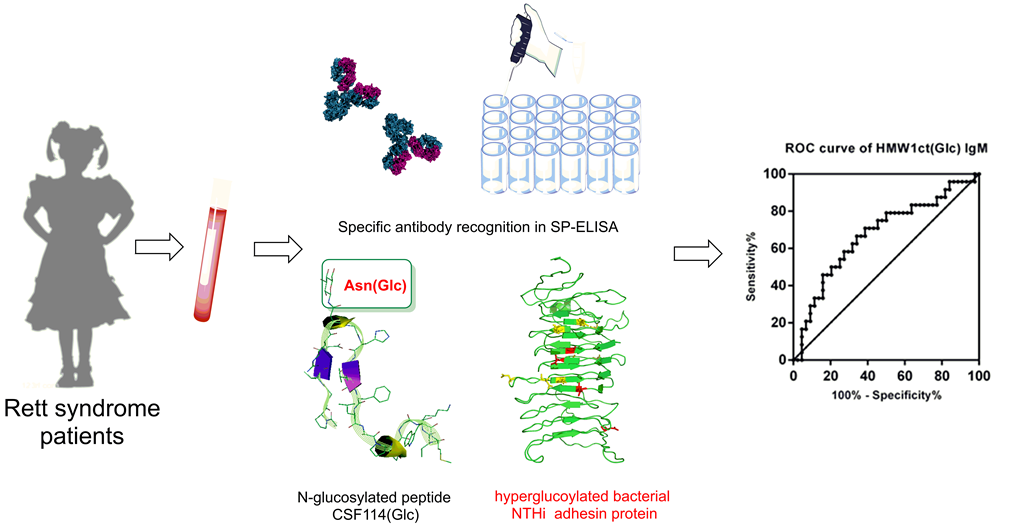

Consequently, we report herein the hypothesis that an autoimmune component derived from environmental bacterial infection may coexist in RTT. At this purpose we screened RTT syndrome patients’ sera in comparison with control sera from non-RTT pervasive developmental disorders (non-RTT PDD) patients and healthy subjects, with the hyperglucosylated adhesin protein HMW1ct(Glc) used as a precise antigen in ELISA in order to identify specific antibodies to N-glucosylation sites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein Expression

2.1.1. General Procedure for Protein Expression

Protein HMW1ct and the enzyme HMW1C were expressed similarly to a described protocol [

15], using E. coli BL21 cells previously engineered with plasmid pET-45b (+) (Merck, Milano, Italy), encoding for the fragment HMW1ct and equipped with the gene for carbenicillin resistance, and plasmid pET-24a (+), encoding for the glucosyltransferase enzyme ApHMW1C and equipped with the gene for kanamycin resistance. Cell cultures were prepared using Luria-Bertani (LB) culture soils. Stock solutions of antibiotics were prepared in H

2O Milli-Q and stored at -20°C. Working concentration in cell media is 50 μg/mL for kanamycin (only for hyperglucosylated HMW1ct(Glc) and 100 μg/mL for carbenicillin. Lysis buffer (pH 7.5) was composed of 5.96 g of HEPES (50 mM), 2.92 g of NaCl (100 mM) and 50 ml of glycerol (10%) dissolved in 0.5 L of H

2O Milli-Q. The HMW1Act-Glc and/or HMW1Act E. coli glycerol stocks were incubated overnight at 37°C in a 5-mL culture containing the carbenicillin or kanamycin antibiotic(s) under shaking. Subsequently, the bacteria were grown in 1 L of the same LB medium (SOC) liquid soil. The solution was incubated under shaking at 37 °C. Cell growth was monitored measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD

600) with an UV instrument (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK). The same LB medium (SOC) liquid soil was used as blank. When the OD value reached 0.6-0.8, the induction of the expression was performed adding 1mM solution of isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cell suspension was incubated overnight at 16°C under shaking. Cells were recovered through centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and the final pellet is washed 3x with PBS buffer, recentrifuged and stored at -20°C.

2.1.2. General Procedure for Protein Purification

The pellet was suspended in 30 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol) adding 10 μL/g of cells of protease inhibitor (cocktail Set III EDTA-free, Merk, Milano, Italy). Mechanical lysis of the cell membrane was obtained by using an ultrasonic processor. The lysis solution was then centrifuged for 110 min at 35000 rpm and the supernatant containing the product(s) was recovered. The purification was performed using an Äkta FPLC system (Amersham Biosciences, Cytiva Italy Srl, Milano, Italy). During the first purification step a Hi Trap-His column (HisTrap HP 5 mL) was used with the binding buffer A1 for Hi Trap-His (30 mM imidazole, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, (pH 7.5, 5% glycerol) and the elution buffer B1 for Hi Trap-His (300 mM imidazole,50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol).

The conditioning of the column was performed using buffer A1 for 10 min. The supernatant containing the products was then injected and eluted with a gradient from 0% to 100% of buffer B1. The UV detector was set to 280 nm and 215 nm. All the fractions obtained were analyzed through Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate - PolyAcrylamide Gel Electrophoresis technique (SDS-PAGE).

The separation of HMW1ct(Glc) from ApHMW1C was obtained in the second purification step through the ion exchange technique. A Hi Trap Q-FF (5 mL, GE Healthcare) column was used. A buffer exchange in order to substitute buffer B1 with binding buffer A2 (20 mM Tris buffer, 20 mM NaCl, pH 8) for Hi Trap Q-FF was performed using Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filters (MWCO = 10 kDa). The Hi Trap Q-FF column was then conditioned with buffer A2 for 10 minutes. The sample was injected and eluted using a linear gradient from 0% to 100% of elution buffer B2 (20 mM Tris buffer, 1 M NaCl, pH 8) for Hi Trap Q-FF. The UV detector was set to 280 nm and 215 nm. All the fraction obtained were analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Both HMW1ct and HMW1ct(Glc) were stocked in PBS buffer (8 g of NaCl, 0.2 g of KCl, 1.44 g of Na2HPO4 and 0.24 g of KH2PO4 dissolved in 1 L of H2O Milli-Q) at -20 °C. Their concentration was calculated using the Lambert-Beer law after an absorption measure performed using an UV spectrometer (Varian Cary 4000, Agilent, Santa Clara, California, USA) set to a range from 320 and 240 nm.

2.1.3. General Procedure for SDS-PAGE

The SDS-PAGE gel was prepared by depositing between two glasses the running 16% gel solution, composed of 1.6 mL H2O Milli-Q, 4.27 ml 30% acrylamide, 2 ml 1.5M tris buffer pH 8.8, 80 μl 10% SDS, 80 μl 10% ammonium persulfate (APS), 10 μl tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED). After the polymerization, the 4% stacking gel solution (1.8 ml H2O Milli-Q, 0.4 ml 30% acrylamide, 0.750 ml 0.5M TRIS buffer pH 6.8, 30 μl 10% SDS, 30 μl 10% APS, 6 μl TEMED) was deposited above the previous one inserting the comb for the formation of the wells. After polymerization, the gel was positioned inside the SDS-PAGE apparatus (Biorad, Segrate, Milano, Italy) and the tank buffer 1x (100 mL of Tris buffer/Glycine/SDS (10x) in 1 L) was added. 10 μL of each sample were combined with 5 μL of loading buffer 5x (200 mM of Tris-Cl (pH 6,8), 400 mM of DTT, 8% of SDS, 0,4% of bromophenol blue and 40% of glycerol), treated at 100 °C for a few minutes and centrifuged. Each sample was then loaded in the dedicate well. The commercial marker PageRuler Plus Prestained Protein Ladder, 10 to 250 kDa, was used as reference. The electrophoresis was performed for 90 min at 140 mV and subsequently the gel subjected to stain using a Comassie solution (25 ml H2O Milli-Q, 20 ml MeOH, 5 ml AcOH, 0.05 g Comassie blue dye) for 30 min. In order to remove the excess dye, the stained gel was treated overnight with a destaining solution (700 ml H2O Milli-Q, 200 mL MeOH, 100 mL AcOH) under gentle shaking.

2.2. Solid-Phase Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

All ELISA parameters, including plates, coating conditions, reagent dilutions, buffers and incubation times were previously optimized. Samples were tested in triplicates and blanks were tested using FBS buffer instead of sample sera at identical conditions. The absorbance value for each serum was calculated as (mean Abs of serum triplicate) − (mean Abs of blank triplicate). One positive and one negative serum, as references, were included in each plate for further normalization.

2.2.1. Sample Collection

In this study, a total of 60 samples including patients and healthy controls were enrolled. The RTT group consisted of 24 patients (mean age 19.13 ± 8.99 years) subdivided into n = 15 (63%) with classical clinical presentation with proven MeCP2 gene mutation and n = 9 (37%) atypical presentation. All the patients were anonymous and recruited in the Child Neuropsychiatric Unit, University Hospital “Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese”, Siena (Italy), during the study. Criteria for inclusion in the study were clinical diagnosis of RTT syndrome coupled with positive identification for the presence/absence of mutated MeCP2, CDKL5, or FOXG1 genes. A group of non-RTT PDD group consisted of 20 patients (mean age 8.8 ± 8.4 years) diagnosed based on well-established criteria. Patients were recruited from those attending the unit for routine clinical follow-up. Blood samplings in the patients’ group were performed during the routine follow-up study at hospital admission, while the samples from the control group were carried out during routine health checks, sports, or blood donations, obtained during the periodic clinical checks. The healthy control subjects were 24 samples (mean age 11.62 ± 4.63 years) age-matched. After collection, blood was immediately centrifuged at 4 °C, 1700 g for 20 min then the sample was frozen to ‒20 °C until analysis.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of “Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese” Study ID number 11615 code OMEGA3 SIENA title “Supplementazione con acidi grassi polinsaturi omega-3 in pazienti con syndrome di Rett” principal investigator Joussef Hayek. Parents, tutors, or guardians of all the participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

2.2.2. Solid-Phase ELISA

ELISA conditions were previously optimized employing antigens for the detection of antibodies in MS sera [

15,

21].

Briefly, 96-Well activated Polystyrene ELISA plates (NUNC Maxisorp, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) were coated with 1 µg/100 µL/well of antigen in coating buffer and incubated at 4 °C overnight. After 3 washes with saline tween, non-specific binding sites were blocked with blocking buffer at room temperature (r.t.) for 60 min. Sera diluted 1:100 in blocking buffer (100 µL/well) were added and incubated at 4 °C for 16 h. After 3 washes, 100 µL/well of secondary antibody solution [alkaline phosphatase conjugated anti human IgM or IgG Fab2-specific affinity purified antibodies (Merck, Milano, Italy) diluted in blocking buffer] were added. After 3 h incubation at r.t., plates were washed 3 times and then 100 µL/well of substrate solution (p-nitrophenylphosphate 0.1% w/v in carbonate buffer and MgCl2 10 mM) were added. After 15 min (IgG plates) or 40 min (IgM plates), the reaction was blocked with 50 µL of 1 M NaOH and the absorbance read in a plate reader (SUNRISE, TECAN, Cernusco Sul Naviglio, Italy) at 405 nm. Mean absorbance values at 405 nm subtracting the blank are reported.

2.2.3. Competitive ELISA

Stock solution of the coating antigen (1 mg/mL) was diluted 1:100 in PBS pH 7.2 (HMW1 and HMW1ct(Glc). 100 µL of coating antigen solution were added to each well (1 µg antigen/well) in a 96-well ELISA plate (NUNC Maxisorp, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), and incubate overnight at 4 °C. The plate was washed three times with 0.9% w/w saline solution containing 0.05% v/v tween 20 (saline tween). 100 µL of Fetal Bovine Serum solution (FBS 10% in saline tween) well were added and the plate was incubated 2 h at temperature.t.. Then the plate was emptied and a mixture of sera and competing antigen was added in each well. Serum concentration was constant (dilution 1:200) while competing antigen concentrations were between 10-11 and 10-5M.

The plate was incubated 1h at r.t., washed three times, and then 100 µL of secondary antibody solution (alkaline phosphatase conjugated anti human IgM or IgG Fab2-specific affinity purified antibodies)/well were added and incubated 3 h at r.t. Plates were washed three times. 100 µL/well of substrate solution (p-nitrophenylphosphate 1mg/mL in carbonate buffer and MgCl2 10 mM) were added. After 30-60 min, the reaction was blocked by adding 50 µL NaOH 1M/well and the final absorbance value was measured with a plate reader at 405 nm (Tecan-Sunrise spectrophotometer, Cernusco Sul Naviglio, Italy).

Peptide concentration-absorbance relationship was represented graphically as signal inhibition percentage, and half-maximal response concentration values (IC50) were calculated with GraphPad Prism software version 6.01.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Solid-Phase ELISA

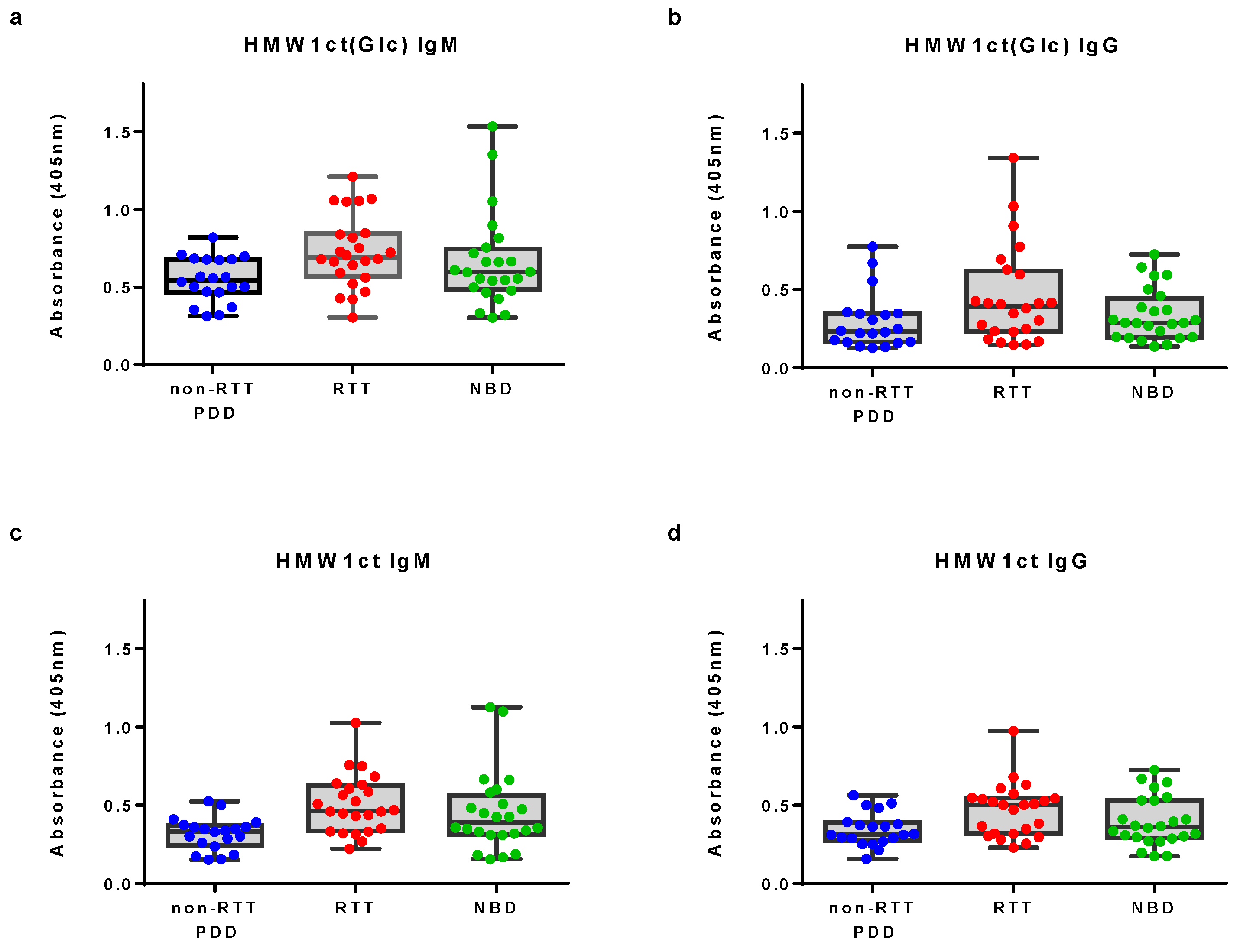

Sera from 24 Rett syndrome (RTT) patients, 20 non-RTT pervasive developmental disorders (non-RTT PDD) patients and 24 healthy subjects have been screened in solid phase ELISA using the hyperglucosylated protein HMW1(Glc) and the corresponding unglucosylated protein HMW1ct as antigens. Clinical characteristics of the selected patients are summarized in the experimental section.

Antigens have been coated in 96-well microplates to identify antibodies in sera. The protocol employed was previously described [

15] with minor modifications. Data distribution of IgM and IgG antibody reactivity to proteins HMW1ct(Glc) and HMW1ct in solid-phase ELISA are summarized in

Figure 1.

Antibody titers to hyperglucosylated HMW1ct(Glc) appeared sightly increased in the RTT group particularly in the case of IgM antibody titers (Kruskal-Wallis test statistic 6.624 and 4.801, P value = 0.0364 and 0.0907 for IgM and IgG, respectively). This result is particularly interesting and supports the hypothesis that the immune system developed specific IgM to the N-glucosylated HMW1ct(Glc) after a possible non-typeable (NTHi)

H. influenzae infection, also confirmed by the lower absorbance signals detected with the unglucosylated protein HMW1ct. This result is in agreement with the diagnostic value of IgM antibodies to an N-glucosylated synthetic type I’ β-turn peptide probe was previously described both in MS and RTT [

12,

18,

19].

On the other hand, it is noteworthy that the moderately high titers observed for both antigens HMW1ct(Glc) and HMW1ct in NBD sera is not surprising since NTHi is a rather ubiquitous human pathogen to which most people have been exposed. In fact, the presence of antibodies against unglucosylated epitopes shared by both proteins has been previously reported and unequivocally demonstrated in the case of MS. In any case, patient sera revealed to be highly populated with antibodies against the hyperglucosylated protein HMW1ct(Glc), suggesting the recognition of an epitope specifically displayed on the glucosylated HMW1ct(Glc) protein as in the previously described case in MS [

15].

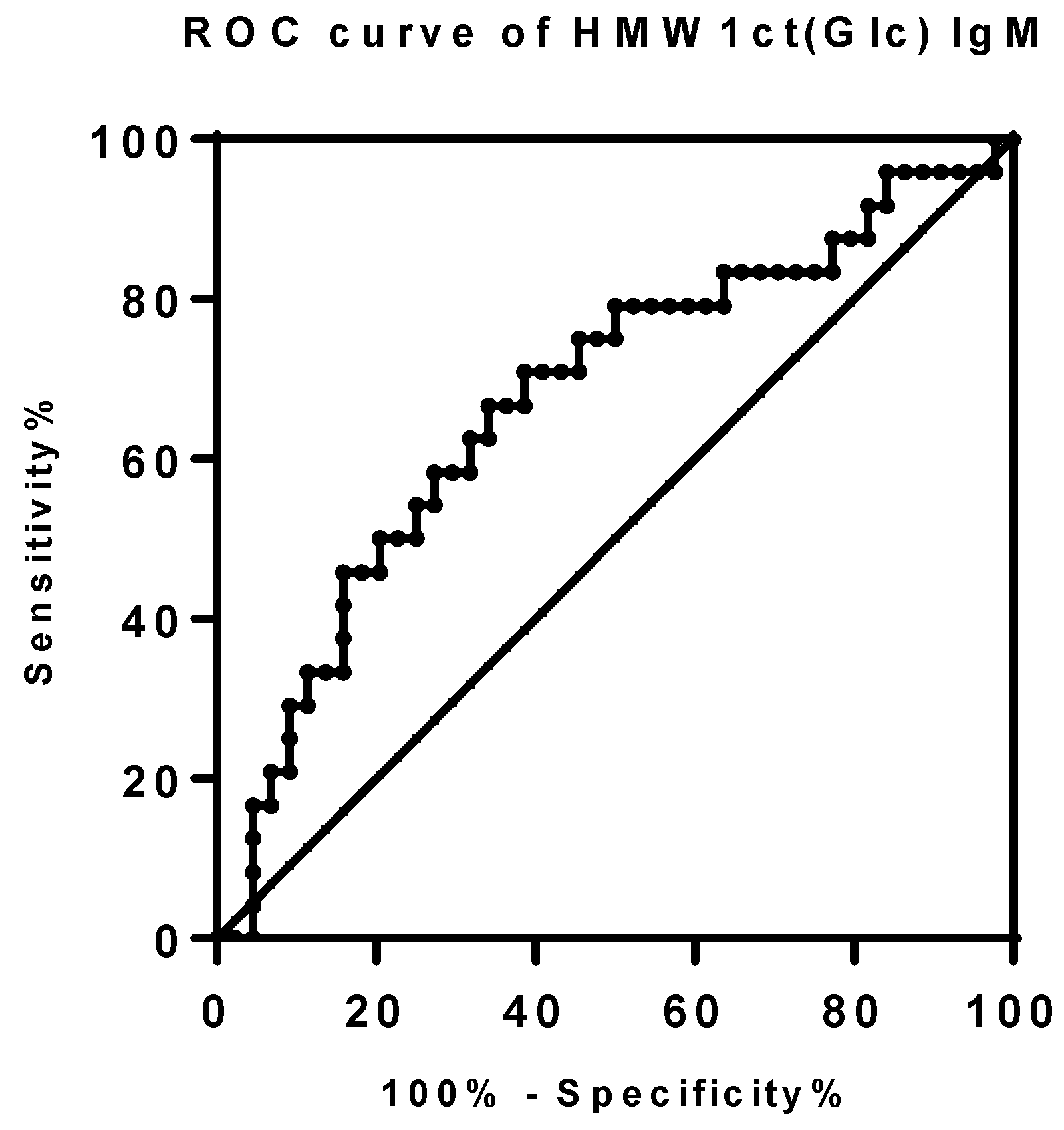

The power of IgM antibody binding levels to HMW1ct(Glc) was also investigated by the Receiver Operator Curve (ROC) analysis comparing different values as sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios [

22]. ROC-curve for IgM antibody activity was calculated based on the 24 RTT cases versus both the non-RTT PDD and the healthy samples for a total of 44 controls (

Figure 2). The area under the curve was 0.6752 (0.5377 to 0.8127, 95% confidence interval, P value < 0.01763). The optimal cut-off absorbance value was set-up at 0.7202 with 45.83% (25.55% to 67.18%, 95% CI) sensitivity, 84.09% (69.93% to 93.36%, 95% CI) specificity with a likelihood ratio of 2.881. Applying the selected cut-off, the presence of specific IgM to HMW1ct(Glc) was quantified in 11 out of 24 (46%) RTT patient sera. Then, protein antigen HMW1ct(Glc) was able to recognize both specific IgM antibodies in RTT patients suggesting the involvement of a bacterial infection in the immune response.

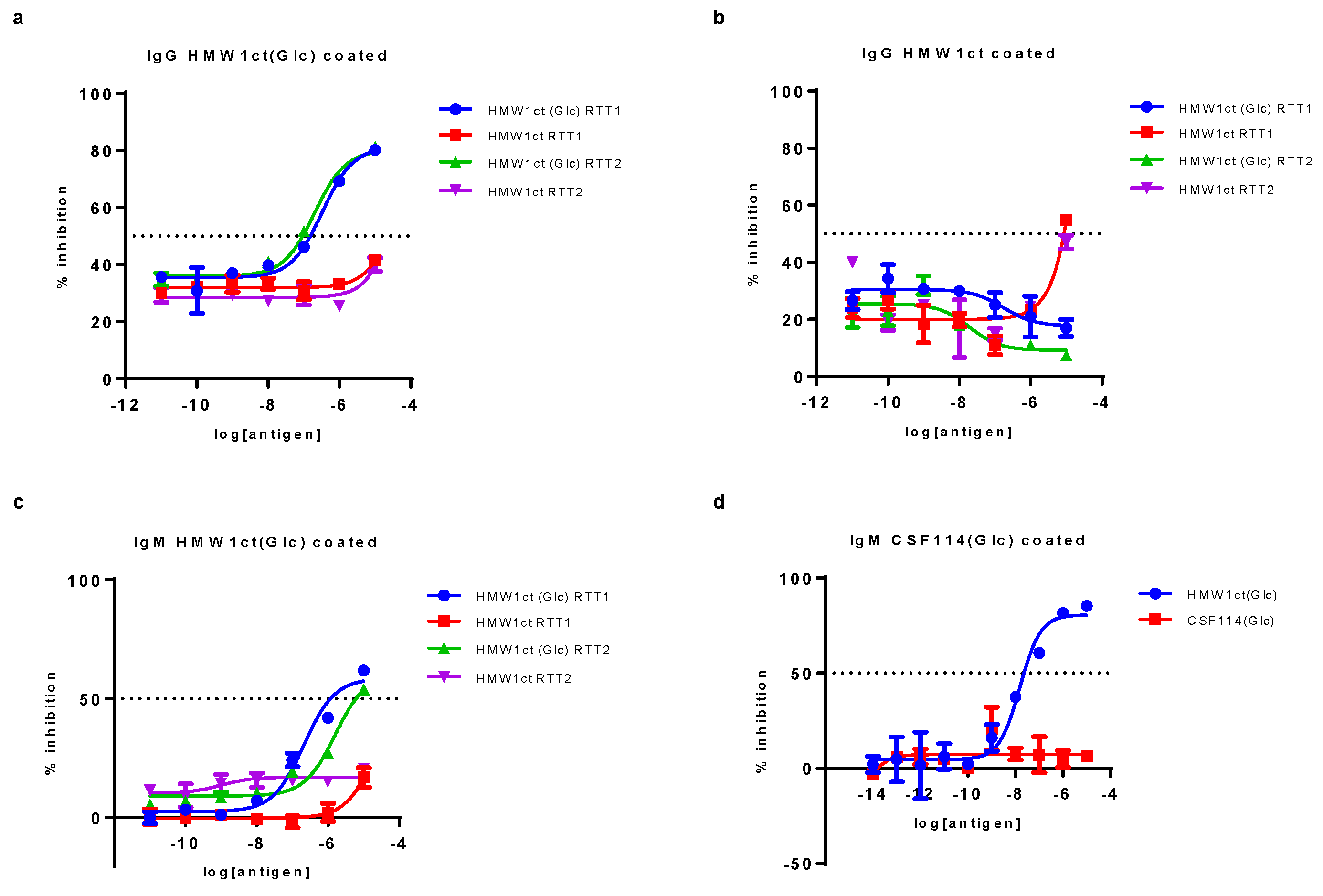

3.2. Competitive ELISA

The autoantibody recognition, using HMW1ct(Glc) and HMW1ct as antigens, was also evaluated by competitive ELISA on two representative RTT patient sera using the proteins as both inhibitors and coating agents. The selection of sera was based on a previous titration by SP-ELISA with proteins, to identify those presenting high IgG and IgM antibody titers. Competitive ELISA results are summarized in

Figure 3.

Results clearly showed that the hyper N-glucosylated HMW1ct(Glc) was able to inhibit the binding of IgG and IgM antibodies in sera from a selected population of representative RTT patients (mean IC50 = 2.64 ± 0.9 x 10

-7 M and 9.01 ± 0.9 x 10

-7 M for IgG and IgM respectively,

Figure 3 pannels a and c). In contrast, non-glucosylated protein HMW1ct did not inhibit, or only inhibited RTT1 serum binding at significantly higher concentrations (

Figure 3, pannel b), confirming the fundamental role of the N-glucosyl moieties on the adhesin protein for the interaction with anti-N-glucosyl antibodies in RTT patient sera. Moreover, results using the N-glucosylated peptide CSF114(Glc) as antigen in competitive ELISA experiments showed that HMW1ct(Glc) was able to inhibit IgM anti-CSF114(Glc) antibodies, whereas the peptide CSF114(Glc) was not able (

Figure 3, pannel d). Indeed, generally speaking in the case of anti-N(Glc) antibodies in MS, the evidence that only competition tests for IgGs, but not those for IgMs, had success when peptide sequences area studied as antigens may be due to two different reasons [

23,

24]. From a practical point of view, anti-N(Glc) IgGs, which possess higher affinity compared to IgMs, are often present in sera, therefore hampering the outcome by binding free target antigens and preventing IgM inhibition. Secondly, high-avidity, pentameric IgM, possessing ten identical antigen binding sites, may be difficult to displace without a very high affinity ligand [

23]. Then, the multivalent presence of N-glucosylations in the HMW1ct(Glc) protein was enough to inhibit anti-CSF114(Glc) IgM binding in serum RTT1, assessing the cross-reactivity between the bacterial HMW1ct(Glc) protein and the previously developed antigenic peptide CSF114(Glc).

5. Conclusions

Rett syndrome is considered and classified as a genetic disease related exclusively to a specific mutation on the MeCP2 directly linked to the X chromosome. RTT is in any case characterized by a very complex phenotype, suggesting the involvement of several factors in its pathogenesis and development. The hypothesis that not only genetics but also dysregulation of the immune system is involved in the syndrome (allowing to stratify all variants of patient populations) is increasingly accepted. Because of the reported similarities between RTT syndrome and well-established autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, we investigated the possible role of the N-glucosylated bacterial protein HMW1ct from NTHi Haemophilus influenzae in the onset of Rett syndrome, which antigenic role in a multiple sclerosis subtype population has been previously demonstrated.

These results highlight that HMW1ct(Glc) is able to significantly detect specific antibodies in RTT sera, thus discriminating RTT patients from controls. Competitive assays on two RTT patient sera featuring higher IgG and IgM antibody titers confirmed the specific interaction between antibodies characteristic of RTT syndrome and the N-glucosylation motifs of the bacterial protein HMW1ct(Glc). These results pave the way for the final assessment that a bacterial infection of NTHi Haemophilus influenzae, for which differently from Haemophilus influenzae no vaccine is available, can trigger an aberrant immune response associated with MECP2 gene mutations that are the cause of most cases of Rett syndrome, a progressive neurologic developmental disorder and one of the most common causes of cognitive disability in females.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.P., F.R.F., and Y.H.; methodology, F.R.F., L.A., and F.N.; formal analysis, F.R.F., P.R., and A.M.P.; investigation, F.R.F., M.H., N.Q., and L.A.; resources, A.M.P., E.P., M.H., N.Q., Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, F.R.F., F.N., and A.M.P.; writing—review and editing, F.R.F., Y.H., P.R. and A.M.P.; visualization, A.M.P.; supervision, A.M.P.; project administration, A.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of “Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese” Study ID number 11615 code OMEGA3 SIENA title “Supplementazione con acidi grassi polinsaturi omega-3 in pazienti con syndrome di Rett” principal investigator Joussef Hayek.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all parents, tutors, or guardians of the subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Rita Levi Montalcini Prize for scientific cooperation between Italy (University of Florence) and Israel (Weizmann Institute of Science, Hebrew University, and Bar Ilan University) to A.M.P. (Israel Council for Higher Education grant 2018, attributed in 2019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chahrour, M.; Zoghbi, H.Y. The Story of Rett Syndrome: From Clinic to Neurobiology. Neuron 2007, 56, 422–437. [CrossRef]

- Mari, F.; Azimonti, S.; Bertani, I.; Bolognese, F.; Colombo, E.; Caselli, R.; Scala, E.; Longo, I.; Grosso, S.; Pescucci, C.; et al. CDKL5 Belongs to the Same Molecular Pathway of MeCP2 and It Is Responsible for the Early-Onset Seizure Variant of Rett Syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics 2005, 14, 1935–1946. [CrossRef]

- Ariani, F.; Hayek, G.; Rondinella, D.; Artuso, R.; Mencarelli, M.A.; Spanhol-Rosseto, A.; Pollazzon, M.; Buoni, S.; Spiga, O.; Ricciardi, S.; et al. FOXG1 Is Responsible for the Congenital Variant of Rett Syndrome. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2008, 83, 89–93. [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, S.R. Rett and Rett-Related Disorders: Common Mechanisms for Shared Symptoms? Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2023, 15353702231209419. [CrossRef]

- De Felice, C.; Leoncini, S.; Signorini, C.; Cortelazzo, A.; Rovero, P.; Durand, T.; Ciccoli, L.; Papini, A.M.; Hayek, J. Rett Syndrome: An Autoimmune Disease? Autoimmunity Reviews 2016, 15, 411–416. [CrossRef]

- Cordone, V. Biochemical and Molecular Determinants of the Subclinical Inflammatory Mechanisms in Rett Syndrome. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2024, 757, 110046. [CrossRef]

- Leoncini, S.; De Felice, C.; Signorini, C.; Zollo, G.; Cortelazzo, A.; Durand, T.; Galano, J.-M.; Guerranti, R.; Rossi, M.; Ciccoli, L.; et al. Cytokine Dysregulation in MECP2 - and CDKL5 -Related Rett Syndrome: Relationships with Aberrant Redox Homeostasis, Inflammation, and ω -3 PUFAs. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2015, 2015, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Zalosnik, M.I.; Fabio, M.C.; Bertoldi, M.L.; Castañares, C.N.; Degano, A.L. MeCP2 Deficiency Exacerbates the Neuroinflammatory Setting and Autoreactive Response during an Autoimmune Challenge. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 10997. [CrossRef]

- Klushnik, T.P.; Gratchev, V.V.; Belichenko, P.V. Brain-Directed Autoantibodies Levels in the Serum of Rett Syndrome Patients. Brain and Development 2001, 23, S113–S117. [CrossRef]

- Gratchev, V.V.; Bashina, V.M.; Klushnik, T.P.; Ulas, V.Ur.; Gorbachevskaya, N.L.; Vorsanova, S.G. Clinical, Neurophysiological and Immunological Correlations in Classical Rett Syndrome. Brain and Development 2001, 23, S108–S112. [CrossRef]

- Ramaekers, V.; Sequeira, J.; Artuch, R.; Blau, N.; Temudo, T.; Ormazabal, A.; Pineda, M.; Aracil, A.; Roelens, F.; Laccone, F.; et al. Folate Receptor Autoantibodies and Spinal Fluid 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate Deficiency in Rett Syndrome. Neuropediatrics 2007, 38, 179–183. [CrossRef]

- Lolli, F.; Mulinacci, B.; Carotenuto, A.; Bonetti, B.; Sabatino, G.; Mazzanti, B.; D’Ursi, A.M.; Novellino, E.; Pazzagli, M.; Lovato, L.; et al. An N-Glucosylated Peptide Detecting Disease-Specific Autoantibodies, Biomarkers of Multiple Sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102, 10273–10278. [CrossRef]

- Lolli, F.; Mazzanti, B.; Pazzagli, M.; Peroni, E.; Alcaro, M.C.; Sabatino, G.; Lanzillo, R.; Brescia Morra, V.; Santoro, L.; Gasperini, C.; et al. The Glycopeptide CSF114(Glc) Detects Serum Antibodies in Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Neuroimmunology 2005, 167, 131–137. [CrossRef]

- Nuti, F.; Fernandez, F.R.; Sabatino, G.; Peroni, E.; Mulinacci, B.; Paolini, I.; Pisa, M.D.; Tiberi, C.; Lolli, F.; Petruzzo, M.; et al. A Multiple N-Glucosylated Peptide Epitope Efficiently Detecting Antibodies in Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Sciences 2020, 10, 453. [CrossRef]

- Walvoort, M.T.C.; Testa, C.; Eilam, R.; Aharoni, R.; Nuti, F.; Rossi, G.; Real-Fernandez, F.; Lanzillo, R.; Brescia Morra, V.; Lolli, F.; et al. Antibodies from Multiple Sclerosis Patients Preferentially Recognize Hyperglucosylated Adhesin of Non-Typeable Haemophilus Influenzae. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 39430. [CrossRef]

- Khattak, Z.E.; Anjum, F. Haemophilus Influenzae Infection. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Quagliata, M.; Nuti, F.; Real-Fernandez, F.; Kirilova Kirilova, K.; Santoro, F.; Carotenuto, A.; Papini, A.M.; Rovero, P. Glucopeptides Derived from Myelin-relevant Proteins and Hyperglucosylated Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae Bacterial Adhesin Cross-react with Multiple Sclerosis Specific Antibodies: A Step Forward in the Identification of Native Autoantigens in Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Peptide Science 2023, 29, e3475. [CrossRef]

- Real Fernández, F.; Di Pisa, M.; Rossi, G.; Auberger, N.; Lequin, O.; Larregola, M.; Benchohra, A.; Mansuy, C.; Chassaing, G.; Lolli, F.; et al. Antibody Recognition in Multiple Sclerosis and Rett Syndrome Using a Collection of Linear and Cyclic N -glucosylated Antigenic Probes. Biopolymers 2015, 104, 560–576. [CrossRef]

- Papini, A.M.; Nuti, F.; Real-Fernandez, F.; Rossi, G.; Tiberi, C.; Sabatino, G.; Pandey, S.; Leoncini, S.; Signorini, C.; Pecorelli, A.; et al. Immune Dysfunction in Rett Syndrome Patients Revealed by High Levels of Serum Anti-N(Glc) IgM Antibody Fraction. Journal of Immunology Research 2014, 2014, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Cortelazzo, A.; De Felice, C.; Guerranti, R.; Signorini, C.; Leoncini, S.; Pecorelli, A.; Scalabrì, F.; Madonna, M.; Filosa, S.; Della Giovampaola, C.; et al. Abnormal N-Glycosylation Pattern for Brain Nucleotide Pyrophosphatase-5 (NPP-5) in Mecp2-Mutant Murine Models of Rett Syndrome. Neuroscience Research 2016, 105, 28–34. [CrossRef]

- Mazzoleni, A.; Real-Fernandez, F.; Nuti, F.; Lanzillo, R.; Brescia Morra, V.; Dambruoso, P.; Bertoldo, M.; Rovero, P.; Mallet, J.; Papini, A.M. Selective Capture of Anti- N -glucosylated NTHi Adhesin Peptide Antibodies by a Multivalent Dextran Conjugate. ChemBioChem 2022, 23, e202100515. [CrossRef]

- Habbema, J.D.F.; Eijkemans, R.; Krijnen, P.; Knottnerus, J.A. Analysis of Data on the Accuracy of Diagnostic Tests. In The Evidence Base of Clinical Diagnosis; Knottnerus, J.A., Buntinx, F., Eds.; Wiley, 2008; pp. 118–145 ISBN 978-1-4051-5787-2.

- Mazzoleni, A.; Real-Fernandez, F.; Larregola, M.; Nuti, F.; Lequin, O.; Papini, A.M.; Mallet, J.; Rovero, P. Hyperglucosylated Adhesin-derived Peptides as Antigenic Probes in Multiple Sclerosis: Structure Optimization and Immunological Evaluation. Journal of Peptide Science 2020, 26, e3281. [CrossRef]

- Mazzoleni, A.; Mallet, J.-M.; Rovero, P.; Papini, A.M. Glycoreplica Peptides to Investigate Molecular Mechanisms of Immune-Mediated Physiological versus Pathological Conditions. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2019, 663, 44–53. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).