1. Introduction

Prosthetic joint infections (PJIs) are a major cause of failure and revision surgery after joint arthroplasties, and the incidence appears to be increasing: the annual PJI incidence rate in the United States increased from 1.99 % in 2001 to 2.18 % in 2009 [

1]. The goals of treating patients with PJI include eradication of the infection, avoidance of medical and surgical complications, improvement in function and quality of life [

2].

The incidence of PJI following total shoulder replacement is 0.61% over 1-year follow-up [

3]. Three main causative pathogens are recognized:

Cutebacterium acnes as the most common (38.9%), followed by

Staphylococcus epidermidis (14.8%), and

Staphylococcus aureus (14.5% )[

4].This species causes PJI primarily through their ability to adhere to prosthetic materials and produce biofilm, although other virulence factors have been identified [

1].

Oritavancin, a semi-synthetic, long acting lipoglycopeptide (LGP) with potent activity against Gram-positive pathogens, has shown favorable PK/PD, wide distribution volume, good bone penetration, in vitro bactericidal activity against gram positive bacteria, and potential sterilization of biofilm. [

5] Oritavancin is not currently approved for the treatment of PJIs, but thanks to the above-mentioned characteristics, it could represent a particularly appealing molecule for treating these infections, especially in patients with limited therapeutic options, including those not eligible for prosthetic replacement.[

6]

Oritavancin has been approved in recent years by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) as a single 1200 mg intravenous (IV) infusion over 3 hours, but there are studies[

7,

8,

9] and case reports [

10,

11] describing its off-label use in bone and prosthetic-associated infections [

5]. The single-dose and prolonged half-life, offer an alternative to multi-dose daily therapies, allowing earlier hospital discharge [

5] or avoiding hospitalization, since it can be administered in the outpatient setting. Moreover, accumulating evidence, primarily from case reports and observational studies, has demonstrated that continued dosing regimens have been well tolerated and have resulted in clinical cure for many patients with complicated or invasive infections, including PJIs. [

12]

In this report, we describe a case of a late shoulder PJI caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) treated with multiple doses of oritavancin, in which the correct timing of administration of the doses has been guided by therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM).

2. Case Report

The patient is a Caucasian male in his eighties with multiple comorbidities: hypertension, obesity, chronic ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease (stage 3b according to KDIGO classification), and peripheral vascular disease. After a right humeral fracture in 2021, he underwent a reverse total shoulder prosthetic surgery stabilized by metal hoop.

Two years later, he developed an extremely painful swelling and functional impairment of the right shoulder. Radiography revealed irregularity of the prosthetic/bone interface, with a lytic area of the cortex on the medial side of the distal half of the prosthetic stem, an extensive detachment of the periprosthetic bone at the proximal half and increased density and thickness of the soft tissues of the arm.A computed tomography (CT) scan of the right shoulder requested thereafter, showed widespread signs of periprosthetic bone reabsorption and a medium-density pseudo nodular thickening in the subcutaneous tissues of the middle third of the arm.

To confirm the diagnosis of shoulder PJI, a radiolabeled white blood cell scintigraphy (WBCS) was performed, which showed increased uptake of radiolabelled WBC in periprosthetic tissues up to the humeral stem of the prothesis, confirming the diagnosis of PJI.

The patient was then referred to our centre to establish an antibiotic treatment and to evaluate potential surgical options. Given patient's comorbidities and his advanced age, prosthetic replacement was contraindicated, and the only possible surgical option was shoulder arthrodesis which would have implicated a complete loss of joint mobility. This option was declined by the patient. Therefore, the only therapeutic option left was long-term suppressive antibiotic therapy.

On the first visit, the patient was in good clinical condition, reporting pain and impaired mobility of the right shoulder. Physical examination showed the presence of a soft, warm and tender swelling, about 4 cm in diameter, at the middle-third of the right arm, near the surgical wound, with purulent discharge from fistula. He had a slightly increased C-reactive protein (CRP) (1.56 mg/dl) and a white blood cell count (WBC) of 7270 cells/mm3 with 56.3% neutrophils.

An ultra sound guided drainage of the periprosthetic fluid collection was performed, collecting 5 ml of purulent fluid which culture yielded methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) (

Table 1).

The patient received a first dose of 1200 mg intravenously (i.v.) of oritavancin on the 1

st of September (Day 0), a second dose of 1200 mg 20 days later (Day 20) and a third dose 15 days later (Day 35). On Day 35, a blood sample for oritavancin TDM was collected before the third dose (T0) and 3 hours after the end of the infusion (T6h). Oritavancin TDM was performed in plasma, on total drug concentration, using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry-based KIT (CoQua Lab, Turin, Italy). Starting from TDM measurements, area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) for the last dose was calculated using Phoenix WinNonLin software and a non-compartmental model was applied. A pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) target of AUC/minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) (AUC/MIC) higher than 17,568 (for MIC up to 0.5 mg/l) was chosen, according to data reported in literature [

13,

14].

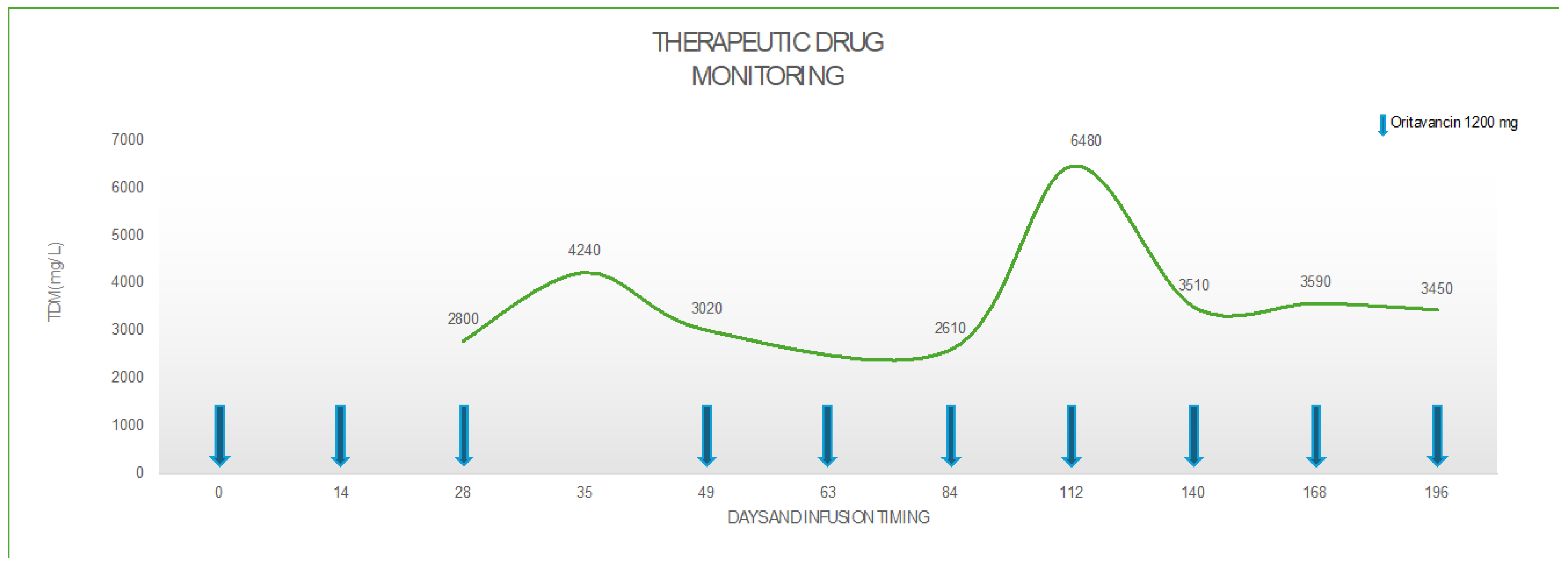

Guided by PK/PD determinations, the following 4

th and 5

th dose were administered each at an interval of 14 days from the previous; the 6

th dose 21 days later and the following doses with and interval of 28 days from the previous ones, once the patient achieved the target trough concentration of oritavancin > 3 mg/L and an AUC/MIC=37,587 at 12 weeks after treatment, as detailed in

Table 2 and

Figure 1.

From a clinical point of view, fourteen days after the first dose of oritavancin, local signs of infection improved, and CRP decreased to 0.94 mg/dl. Fifteen days after the second infusion, i.e. after 35 days of treatment, the fistula at the middle third of the arm resolved, and laboratory tests showed a further decrease of inflammatory markers (CRP 0.64 mg/dl).

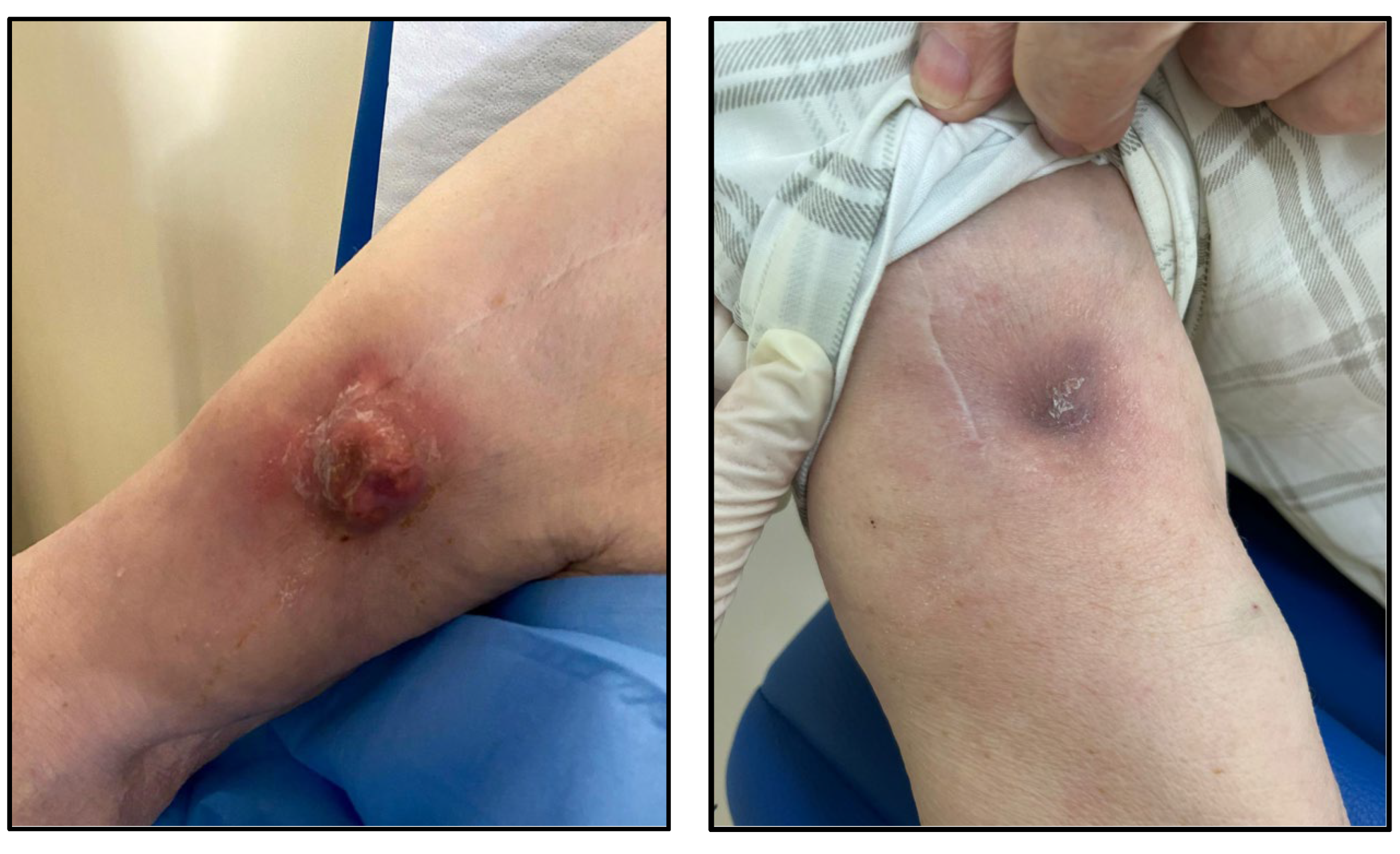

From the third administration, the patient reported a gradual and progressive improvement in pain and mobility. After the sixth dose, i.e. 12 weeks after starting the treatment with oritavancin, the pain disappeared, and the patient completely recovered joint mobility. Physical and US-guided examination showed a complete healing of the fistula and the disappearance of the underlying abscess.

At the time this paper was written, the patient has received ten doses of oritavancin 1200 mg, for a total of 28 weeks of treatment: he has no symptoms and sings of infection and the mobility of the shoulder joint is completely restored (

Figure 2). Suppressive antibiotic treatment with oritavancin is still ongoing with scheduled administration of 1200 mg of oritavancin every 28 days, guided by TDM through concentration. Our aim is to perform a PET-CT scan after 48 weeks of treatment in order to plan an advisable end of the antimicrobial treatment.

3. Discussion

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) of the shoulder can be a devastating complication. Although it may occur less frequently than after lower extremity arthroplasty, PJI of the shoulder can lead to poor functional outcomes, disability and death [

15]. Risk factors for shoulder PJI include previous surgery, increased age, male gender, increased body mass index, and diabetes mellitus [

16].

The management of PJIs depends on the timing of the infection, microbial etiology, the condition of the joint and implant, the quality of the soft tissue, and individual patient circumstances. The three most common surgical techniques include a one-stage exchange procedure (OSE), a two-stage procedure (TSP), a combined approach known as debridement, antibiotics and implant retention (DAIR) [

17], which is only suitable in early infections, within 30 days from surgery [

18]. The goal of each surgical strategy is to remove all infected tissue and hardware or to decrease the burden of biofilm if any prosthetic material is retained, so that postoperative antimicrobial therapy can eradicate the remaining infection [

1].

The ability to grow and persist on the implant surface and on necrotic tissue in the form of a biofilm represents a basic survival mechanism by which microorganisms resist to environmental factors [

19]. After the first contact with the implant, microorganisms immediately adhere to its surface. Mature biofilms take four weeks to develop and represent complex 3D-communities where microorganisms of one or several species live clustered together in a highly hydrated, self-produced extracellular matrix (slime). Depletion of metabolic substances and waste product accumulation cause micro-organisms to enter a slow- or non-growing (stationary) state. Planktonic bacteria can detach at any time, activating the host immune system, causing inflammation, oedema, pain and early implant loosening. Biofilm micro-organisms are up to 1000 times more resistant to growth-dependent antimicrobial agents than their planktonic counterparts [

19,

20].

From a microbiology point of view, Yan et al. evaluated antibiofilm activity of oritavancin in combination with rifampin, gentamicin, or linezolid against 10 prosthetic joint infection (PJI) by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates by time-kill assays: oritavancin combined with rifampin demonstrated statistically significant bacterial reductions compared with those of either antimicrobial alone for all 10 isolates (p≤0.001), with synergy being observed for 80% of the isolates [

28].

Staphylococcus epidermidis causes PJI primarily through its ability to adhere to prosthetic materials and produce biofilm, although other more typical virulence factors have involved as well1 .In recent years, there has been a worrisome increase in the number of surgical site infections caused by methicillin-resistant (MR) organisms and consequently the number of PJIs caused by MR organisms has also risen, accounting for more than one half of cases of PJIs. The management of PJI caused by MR organisms is associated with increased treatment failure, longer hospitalizations, and poor clinical outcomes [

22].

Moreover, in the United States, a study compared the costs of treating infections due to methicillin-resistant germs versus those due to sensitive strains. Significantly higher cost of care for treatment of infections due to methicillin-resistant organisms have been demonstrated (

$107.264 versus

$68.053, p < 0.0001) [

23]. In the setting of MR

Staphylococcus infection, therapeutic options are unfortunately limited with glycopeptides and daptomycin that are considered first line option. However, the development of biofilm should also be considered, and the treatment should include active drugs or a combination of drugs able to penetrate biofilm. [

23,

24]

Given our patient's comorbidities and his advanced age, prosthetic replacement was contraindicated, and the only possible surgical option was shoulder arthrodesis, i.e. fusion of the humeral head to the glenoid, mostly used as an end-stage, salvage procedure. The patient refused arthrodesis since this would have resulted in a complete loss of joint mobility, therefore the only therapeutic option remained a long-term suppressive antibiotic therapy without further surgical interventions.

In our clinical case, the patient has few available oral therapeutic options for suppressive treatment, as long-term administration of oxazolidinones is contraindicated and the prolonged use of clindamycin is associated with high risk of

Clostridioides difficile infections [

24,

25]. Therefore, only intravenous administration of daptomycin or glycopeptides could have been considered as suitable therapeutic options for a long-term treatment, but both would have required a long-term hospitalization, with relevant consequences on healthcare associated infections and costs together with terrible impact on patient's quality of life. To avoid all these unfavorable scenarios, our clinical decision was to prescribe oritavancin 1200 mg i.v. in multiple sequential doses.

Our decision was supported by a few clinical observations that showed safety and efficacy of a multiple-dose regimens for the treatment of complicated and deep-seated Gram-positive infections, such as PJIs [

26]. In fact, a clinical success in 30 of 32 patients (93.8%), including 10 of 11 (90.9%) patients with bone and joint infections has been reported in a cohort of 32 patients who received at least two doses of oritavancin in the CHROME study a multicenter, retrospective, observational study [

27].

Despite several studies reporting the safety and the efficacy of a multi-dose oritavancin regimen for difficult-to-treat infections, there are very few data regarding pharmacokinetics of this dose schedule. In our case, the first two doses of oritavancin 1200 mg have been administered every two weeks. After the second dose, we started TDM of oritavancin to define the correct timing of the following administration. We firstly postpone to 21 days next dose, then, since drug concentrations were still above the target, we extended the interval between doses to 28 days. Thanks to the use of TDM, we noticed that even if administered every 28 days, the oritavancin concentration ranged above the chosen target trough (3.5 mg/L). Therefore, starting from the fourth dose, we established a monthly administration schedule. From the clinical point of view, the efficacy was preserved, and the patient could then make hospital access only once a month, with a great impact on his quality of life. Our case confirms what the SOLO I and II studies have assessed, that a target plasma trough cut-off of 3 mg/L appeared to be associated with therapeutics effectiveness [

29]. Nevertheless, there is an important lack of information for oritavancin TDM, associated with a scant of works describing oritavancin determination in liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC -MS/MS) [

30].

4. Conclusions

Oritavancin could represent an excellent solution for treating prosthetic joint infections, especially for those who need a long-term suppressive therapy as you may both reduce the number of days of hospitalization and ensure better compliance.

Further clinical studies are needed to better understand the pharmacokinetics of this regimen in order to figure out the correct concentration target and therefore the optimal schedule of administration in this setting.

References

- Tande, A. J. & Patel, R. Prosthetic joint infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 27, 302–345 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Ledezma, C., Higuera, C. A. & Parvizi, J. Success after treatment of periprosthetic joint infection: A delphi-based international multidisciplinary consensus infection. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research vol. 471 2374–2382 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Setor K. Kunutsor Matthew C. Barrett Michael R. Whitehouse Richard S. Craig Erik Lenguerrand Andrew D. Beswick Ashley W. Blom. Incidence, temporal trends and potential risk factors for prosthetic joint infection after primary total shoulder and elbow replacement: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Infection 80, 426–436 (2020).

- Faria, G. et al. Prosthetic joint infections of the shoulder: A review of the recent literature. J Orthop 36, 106–113 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lupia, T. et al. Role of Oritavancin in the Treatment of Infective Endocarditis, Catheter- or Device-Related Infections, Bloodstream Infections, and Bone and Prosthetic Joint Infections in Humans: Narrative Review and Possible Developments. Life vol. 13 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Osmon, D. R. et al. Diagnosis and Management of Prosthetic Joint Infection: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of Americaa. Clinical Infectious Diseases 56, e1–e25 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Van Hise, N. W. et al. Treatment of Acute Osteomyelitis with Once-Weekly Oritavancin: A Two-Year, Multicenter, Retrospective Study. Drugs Real World Outcomes 7, 41–45 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Co, D. ; R. L. ; V. J. Evaluation of Oritavancin Use at a Community Hospital. . Hosp. Pharm 272–276 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Schulz, L. T. ; D. E. ; D.-P. J. ; R. W. E. Multiple-Dose Oritavancin Evaluation in a Retrospective Cohort of Patients with Complicated Infections. Pharmacotherapy (2018).

- Delaportas, D. J., Estrada, S. J. & Darmelio, M. Successful Treatment of Methicillin Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus Osteomyelitis with Oritavancin. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy 37, (2017).

- Dahesh, S. et al. Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium Hardware-Associated Vertebral Osteomyelitis with Oritavancin plus Ampicillin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Barnett, S. Continued Dosing of Oritavancin for Complicated Gram-Positive Infections. Federal Practitioner (2020) . [CrossRef]

- Rose, W. E. & Hutson, P. R. A Two-Dose Oritavancin Regimen Using Pharmacokinetic Estimation Analysis. Drugs Real World Outcomes 7, 36–40 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lodise, T. P., Redell, M., Armstrong, S. O., Sulham, K. A. & Corey, G. R. Efficacy and safety of oritavancin relative to vancomycin for patients with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) in the outpatient setting: Results from the solo clinical trials. Open Forum Infect Dis 4, (2017).

- Patel, V. V. et al. Validation of new shoulder periprosthetic joint infection criteria. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 30, S71–S76 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Seok, H.-G., Park, J.-J. & Park, S. Risk Factors for Periprosthetic Joint Infection after Shoulder Arthroplasty: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 11, 4245 (2022).

- Nguyen, J. P. et al. Successful treatment of a prosthetic hip infection due to Enterococcus faecalis with sequential dosing of oritavancin and prosthesis preservation without prosthetic joint surgical manipulation. IDCases 22, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, J., Adeli, B., Zmistowski, B., Restrepo, C. & Greenwald, A. S. Management of Periprosthetic Joint Infection: The Current Knowledge. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 94, e104 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Izakovicova, P., Borens, O. & Trampuz, A. Periprosthetic joint infection: current concepts and outlook. EFORT Open Rev 4, 482–494 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J. W., Stewart, P. S. & Greenberg, E. P. Bacterial Biofilms: A Common Cause of Persistent Infections. Science (1979) 284, 1318–1322 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Abboud, J. A. & Cronin, K. J. Shoulder Arthrodesis. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 30, e1066–e1075 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S., Ong, K., Lau, E., Mowat, F. & Halpern, M. Projections of Primary and Revision Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg 89, 780–785 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, J. et al. Periprosthetic Joint Infection. J Arthroplasty 25, 103–107 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Duffy, C. R. et al. Clindamycin, Gentamicin, and Risk of Clostridium difficile Infection and Acute Kidney Injury During Delivery Hospitalizations. Obstetrics & Gynecology 135, 59–67 (2020).

- Roger, C., Roberts, J. A. & Muller, L. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Oxazolidinones. Clin Pharmacokinet 57, 559–575 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C. L., Turner, M. S., Frens, J. J., Snider, C. B. & Smith, J. R. Real-World Experience with Oritavancin Therapy in Invasive Gram-Positive Infections. Infect Dis Ther 6, 277–289 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Redell, M. et al. The CHROME Study, a Real-world Experience of Single- and Multiple-Dose Oritavancin for Treatment of Gram-Positive Infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 6, (2019).

- Yan, Q., Karau, M. J., Raval, Y. S. & Patel, R. Evaluation of Oritavancin Combinations with Rifampin, Gentamicin, or Linezolid against Prosthetic Joint Infection-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms by Time-Kill Assays. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62, (2018).

- Corey GR, Loutit J, Moeck G, Wikler M, Dudley MN, O'Riordan W; SOLO I and SOLO II investigators. Single Intravenous Dose of Oritavancin for Treatment of Acute Skin and Skin Structure Infections Caused by Gram-Positive Bacteria: Summary of Safety Analysis from the Phase 3 SOLO Studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018 Mar 27;62(4):e01919-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mattox J, Belliveau P, Durand C. Oritavancin: A Novel Lipoglycopeptide. Consult Pharm. 2016 Feb;31(2):86-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qun Yan, M. J. K. Y. S. R. R. P. In vitro activity of oritavancin in combination with rifampin or gentamicin against prosthetic joint infection-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents 52, 608–615 (2018).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).