Submitted:

09 July 2024

Posted:

10 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Components of the Runoff Agricultural System

1.1.1. Dammed Wadis

1.1.2. Slope Systems (Tuleilat el-‘Anab)

1.1.3. Agricultural Installations

Square Field Towers

Industrial Winepresses

Industrial Oil Presses

Livestock Pens

1.2. The Head of the System and the Identity of the Population

2. A Selection of Data from the Field

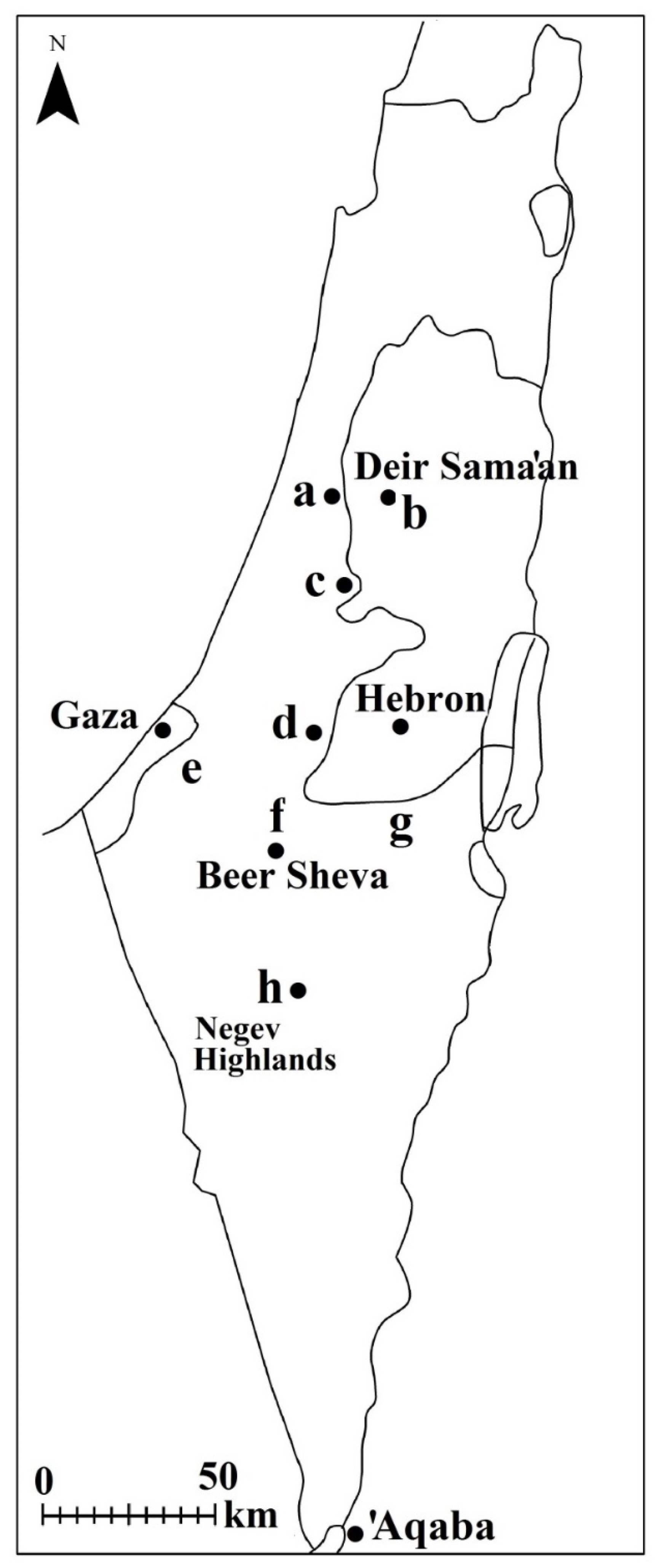

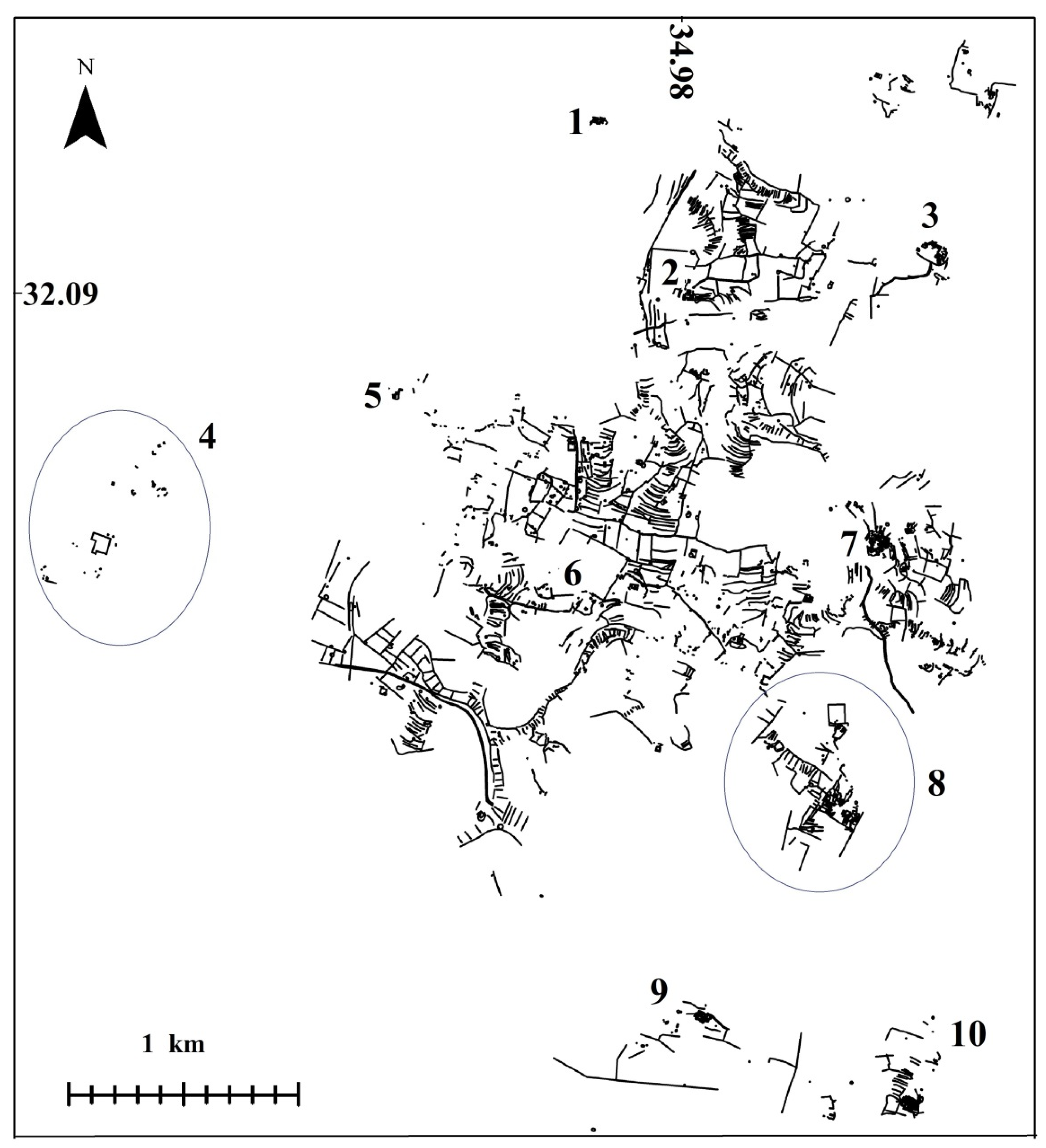

2.1. The Western Samarian Hills (Figures 1.a; 2)

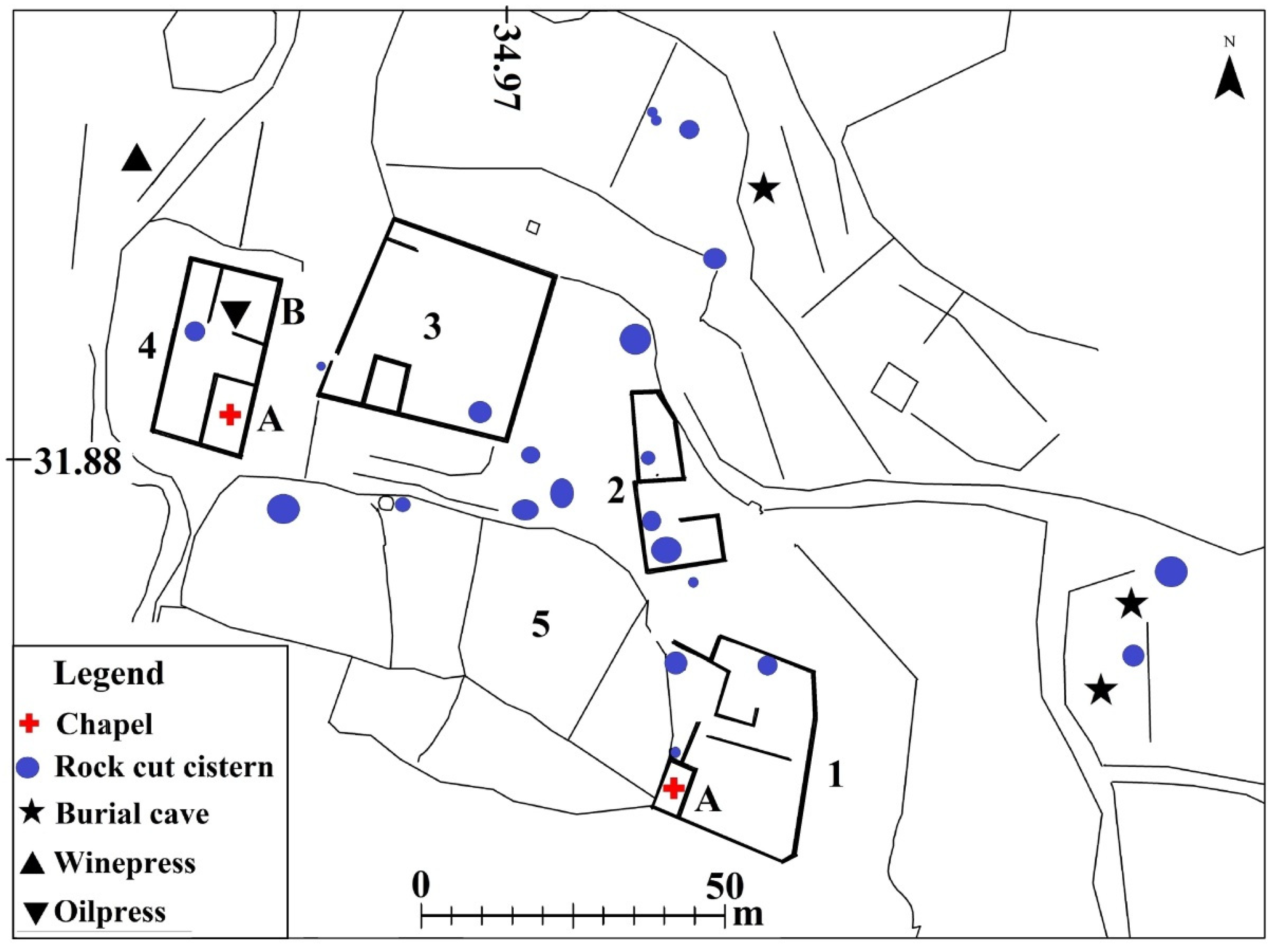

2.1.1. Ḥorvat Dayyar (Figure 2.1)

2.1.2. Ḥorvat Barid (Figure 2.2)

2.1.3. Ḥorvat Kaspah (Figure 2.3)

2.1.4. Migdal Tsedek (Figures 2.4; 3)

2.1.5. Kasr es-Sett (Figure 2.5)

2.1.6. Ḥorvat Teena (Figure 2.6)

2.1.7. Ḥorvat Ḥammam (Figure 2.7)

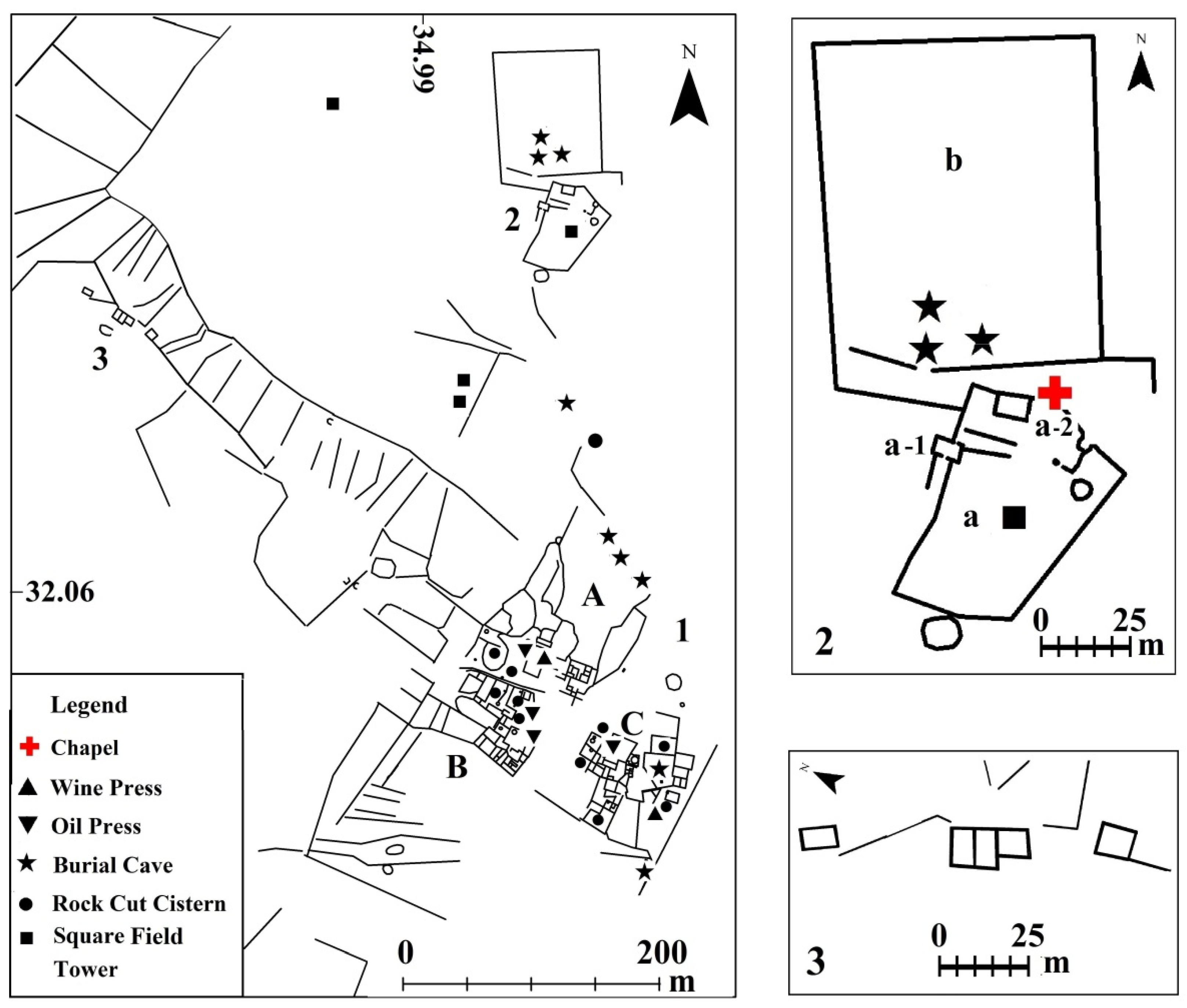

2.1.8. Ḥorvat Yeqavim (Figures 2.8; 4)

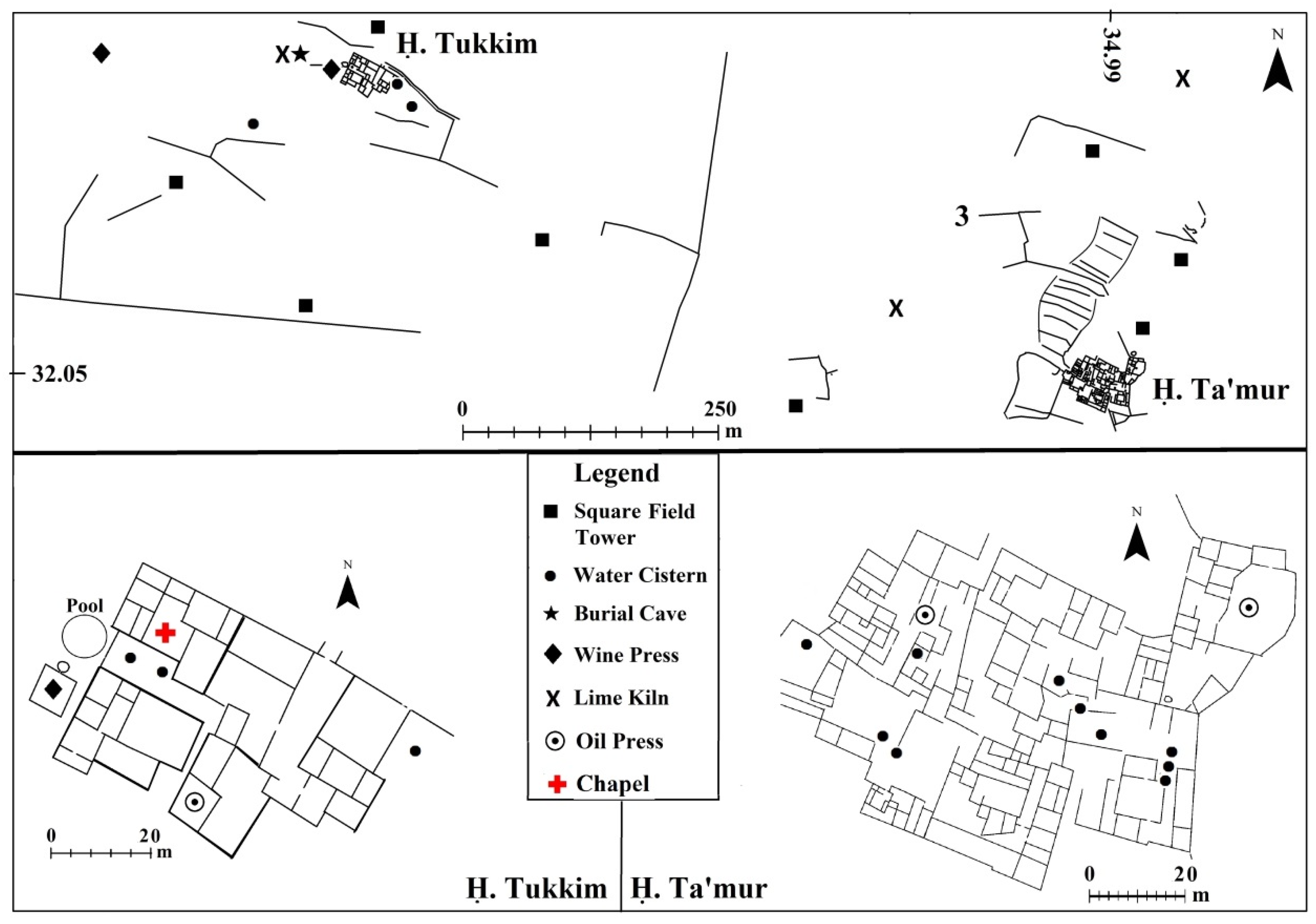

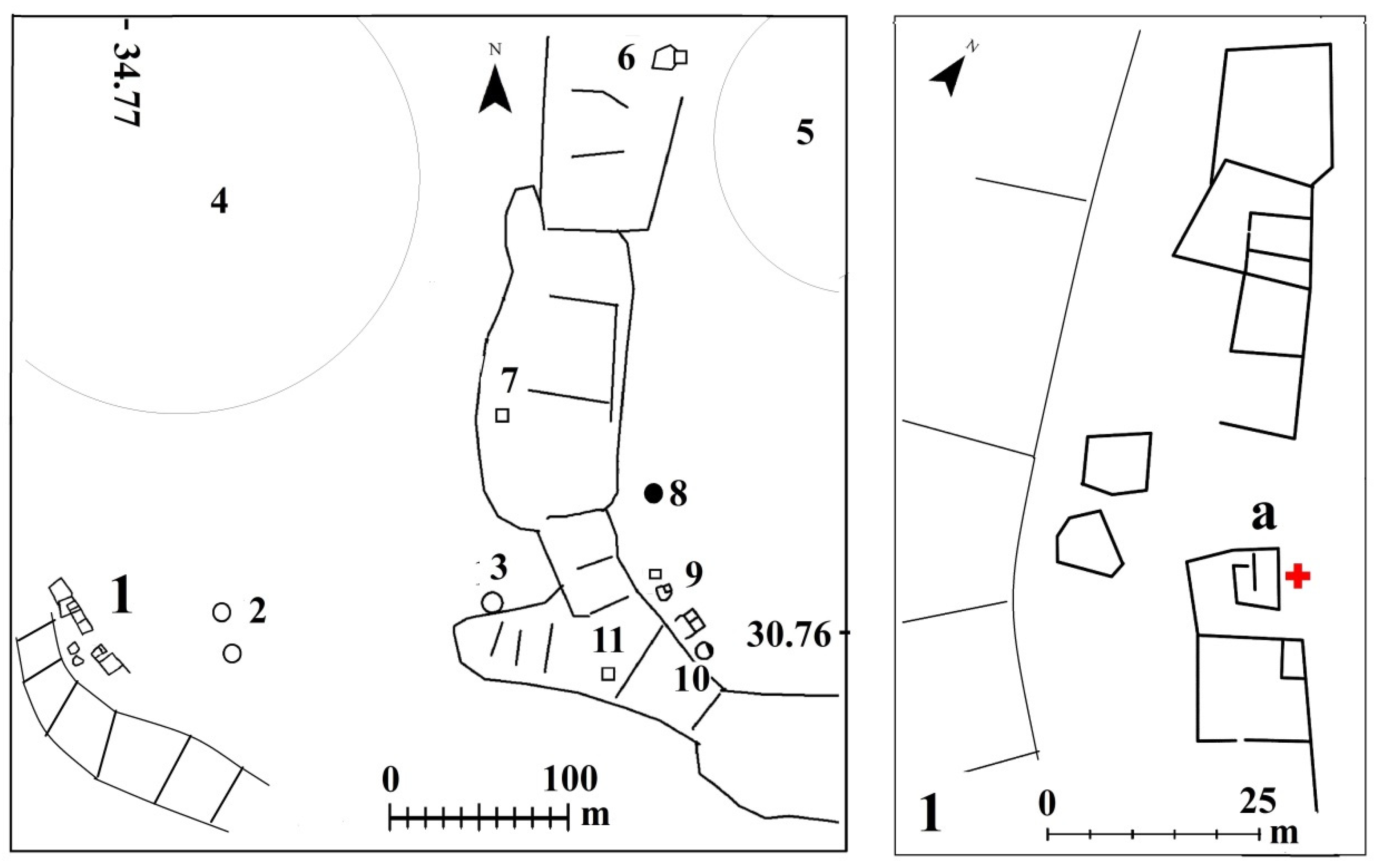

2.1.9. Ḥorvat Tukkim (Figures 2.9; 5)

2.1.10. Ḥorvat Ta‘amur (Figures 2.10; 5)

2.2. Fortified Monasteries in Samaria (Figure 1.b)

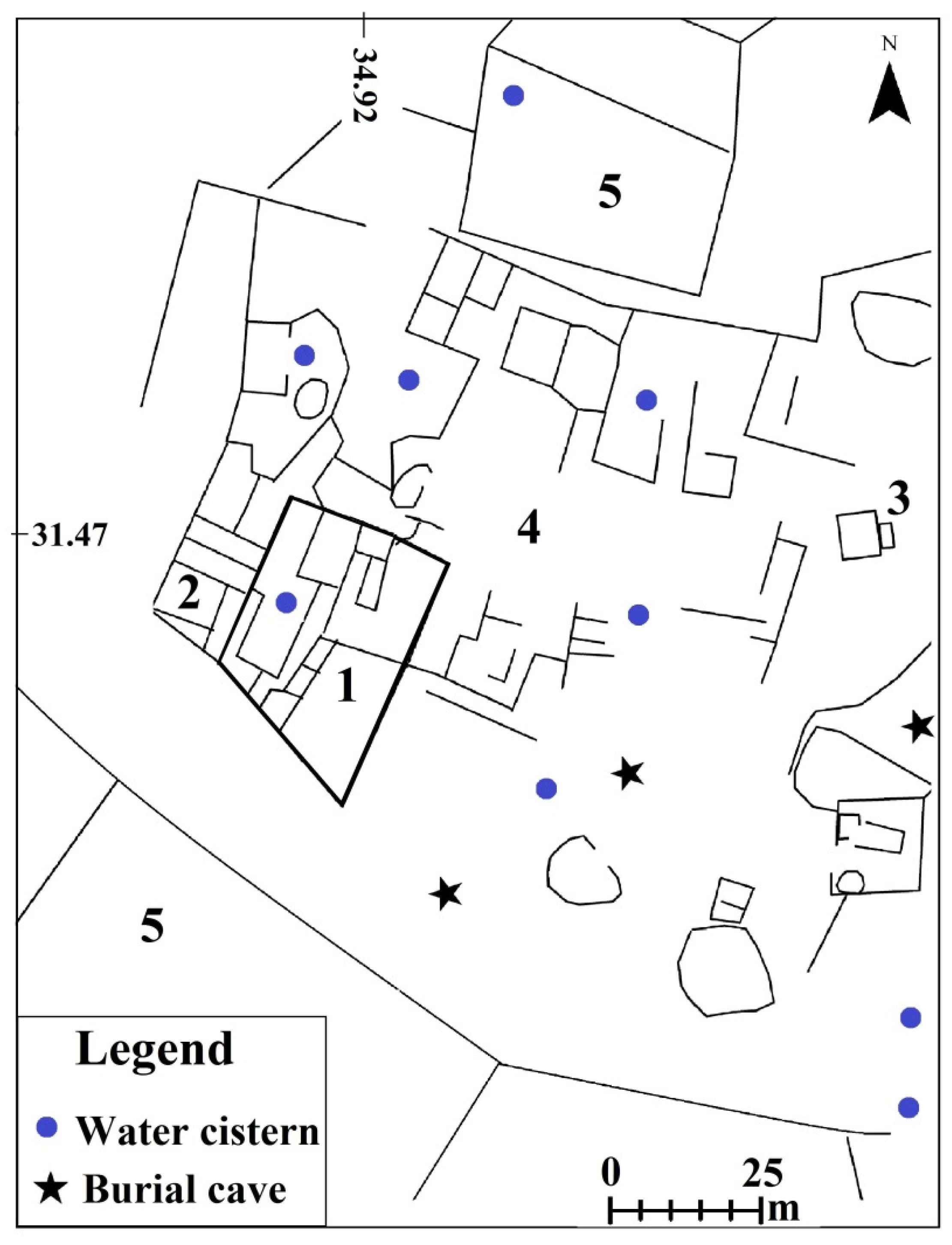

2.3. The Modi‘in Region (Figures 1.c.; 6)

2.4. The Western Hebron Hills (Figures 1.d.; 7)

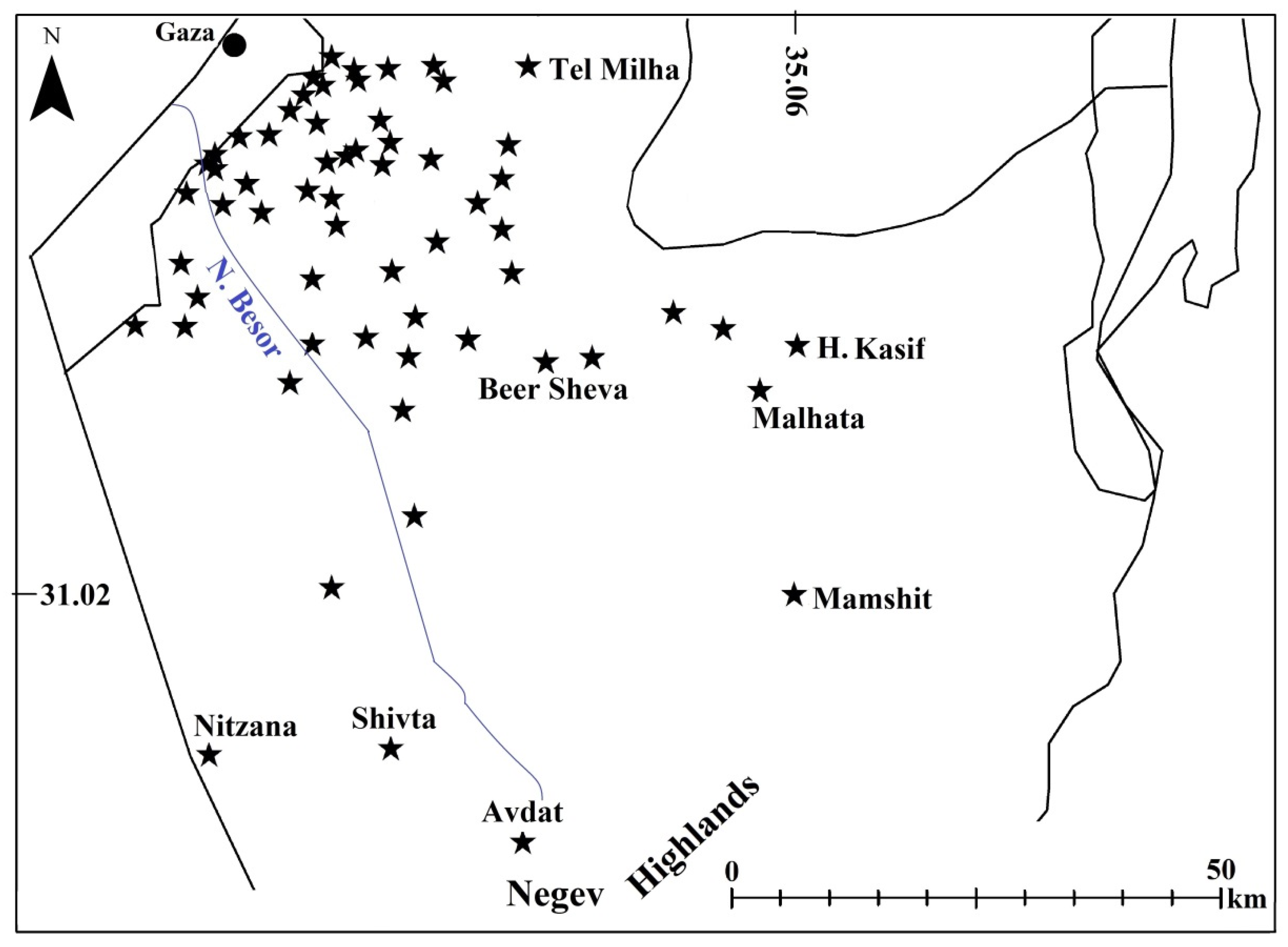

2.5. The Besor Region (Figures 1.e.; 8)

2.6. The Beer Sheva Valley (Figure 1.f.)

2.7. The southern Hebron Hills (Figures 1.g.; 9)

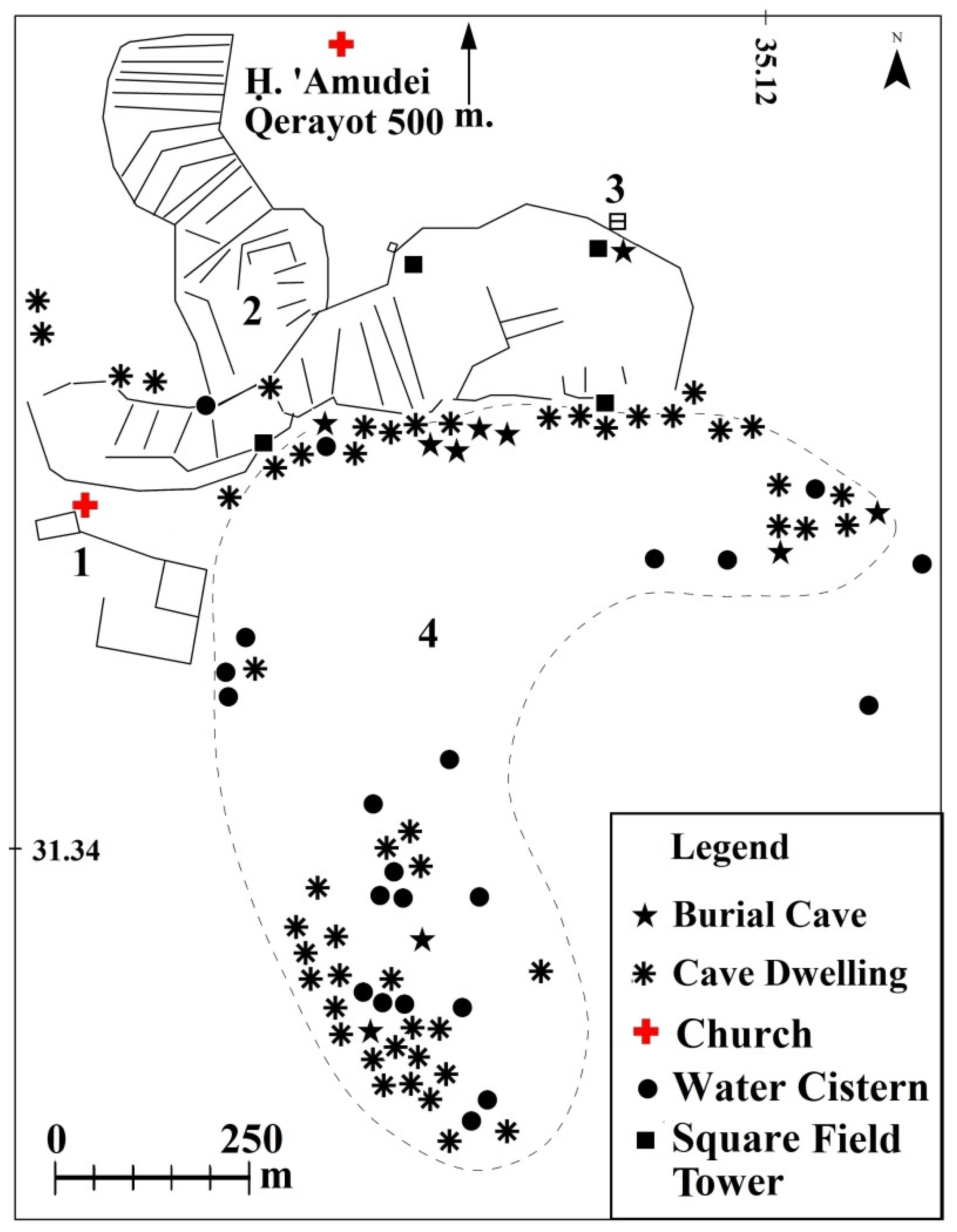

2.8. Outskirts of Avdat (Figures 1.h.; 10)

3. Discussion

3.1. Chronology

The Agricultural Periphery

3.2. Management of the Agricultural Systems

3.3. Focuses of Economic Activity

3.4. Flexible Compatibility to the Surroundings

3.4.1. Compatibility with Local Precipitation

3.4.2. Thickness of the Dam Walls

3.4.3. Runoff Drainage Area

3.4.4. The Effect of the Rain Shadow

3.4.5. Suitability to the Geological-Geomorphological Structure

3.4.6. Suitability of the Location of the Autochthonous Villages

3.4.7. Geopolitical Suitability

4. Conclusions

4.1. The Relevance of the Question of Climate Change in the Levant.

4.2. Global Crises and the Increase in Food Production in the Levant.

4.3. The Effects of Imperial Administration.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ACKERMANN, O., SVORAY, T. and HAIMAN, M. 2008: Nari (Calcrete) outcrop contribution to ancient agricultural terraces in the Southern Shephelah, Israel: insights from digital terrain analysis and a geoarchaeological field survey. Journal of Archaeological Science 35, 930–41.

- ARJAVA, A. 2005: The mystery cloud of 536 CE in the Mediterranean sources, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 59, 73–94.

- ASHKENAZI, E., CHEN, Y., AVNI, Y. and LAVEE, S. 2015: Fruit trees’ survival ability in an arid desert environment without irrigation in the Negev Highlands of southern Israel, Israel Journal of Plant Sciences 62.1–2, 5–16.

- ASHKENAZI, J. and AVIAM, M. 2014: Small monasteries in Galilee in late antiquity: the test case of Karmiel. In BOTTINI, G.C., CHRUPCALA, L.D. and PATRICH, J. (eds.), Knowledge and Wisdom, Archaeological and Historical Essays in Honour of Leah Di Segni (Milano), 161–78.

- AVNI, G. 2014: The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine (Oxford).

- AVNI, G., PORAT, N. and AVNI, Y. 2013: Byzantine-Early Islamic Agricultural systems in the Negev Highlands: stages of development as interpreted through OSL dating. Journal of Field Archaeology 38.4, 332–46.

- AVSHALOM-GORNI, D., FRANKEL, R. and GETZOV, N. 2008: A Complex Winepress from Mishmar ha-ʻEmeq: Evidence for the Peak in the Development of the Wine Industry in Eretz Israel in Antiquity. 'Atiqot 58, 47–66 (Hebrew with English summary).

- AYALON, E. 1997: The end of the ancient wine production in the central coastal Plain. In FRIEDMAN, Y., SAFRAI, Z. and SCHWARTZ, J. (eds.), Hikrei Eretz – Studies in the History of the Land of Israel Dedicated to Prof. Yehuda Feliks (Tel Aviv), 149–66 (Hebrew).

- BARKER, G. (ed.). 1996: Farming the Desert: The UNESCO Libyan Valleys Archaeological Survey, Vol. I (London).

- BITTON-ASHKELONY, B. and KOFSKY, A. 2000: The Monasticism of Gaza in the Byzantine period Cathedra 96, 69–110 (Hebrew with English summary).

- BRUINS, H.J., VAN DER PLICHT, J. and HAIMAN, M. 2012: Desert habitation history by C14 dating of soil layers in rural building structures (Negev, Israel): preliminary results from Horvat Haluqim. In BOARETTO, E. and REBOLLO FRANCO N. R. (eds.), Proceedings of the 6th International Radiocarbon and Archaeology Symposium. Radiocarbon 54.3–4, 391–406.

- COLT, H.D. (ed.) 1962: Excavations at Nessana (Auja Hafir, Palestine), Vol. 1 (London).

- DAR, S. 1986: Landscape and pattern: an Archaeological survey of Samaria, 800 BCE–636 CE (Oxford, BAR IS 308), vols. I–II.

- DAYAN, A. 2015: Monasteries in the Northern Judean Shephelah and the Samaria Western Slopes During the Byzantine and the Early Islamic Periods (Ph.D. thesis, Bar Ilan University) (Hebrew with English summary).

- Di SEGNI, L. 2001: Monk and society: the case of Palestine. In PATRICH, J. (ed.). The Sabaite Heritage in the Orthodox Church from the Fifth Century to the Present (Leuven, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 98) 31–36.

- Di SEGNI, L. 2004: The territory of Gaza: notes of historical geography. In KOFSKY, A. and BITTON-SHKELONY, B. (eds.), Christian Gaza in Late Antiquity (Leiden-Boston, Brill), 41–59.

- EISENBERG-DEGEN, D. and KOBRIN, F. 2016: Be’er Sheba‘, Nahal ‘Ashan, Newe Menahem B. Hadashot Arkheologiyot 128.

- ESHEL, H., MAGNESS, J. and SHENHAV, E. 2000: Khirbet Yattir, 1995–1999: Preliminary Report. Israel Exploration Journal 50, 153–68.

- EVENARI, M., AHARONI, Y., SHANAN, L. and TADMOR, N. 1958: The Ancient Desert Agriculture of the Negev III: Early Beginnings. Israel Exploration Journal 8, 231–68.

- EVENARI, M., SHANAN, L. and TADMOR, N. 1971: The Negev, The Challenge of the Desert (Cambridge, MA).

- FABIAN, P. and GOLDFUS, H. 2004: A Byzantine Farmhouse, Terraces and Agricultural Installations at the Goral Hills near Beʻer Shevaʾ, ʾAtiqot 47, 1*–14*.

- FIEMA, Z.T. 2002: Petra and its Hinterland during the Byzantine Period, New Research and Interpretations. In HUMPHREY, J. (ed.), Roman and Byzantine Near East Volume 3 (Portsmouth, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 49), 191–252.

- FIEMA, Z.T. 2007. The Byzantine Military in the Petra Papyri – a Summary. In LEWIN, A.S. and PELLEGRINI, P. (eds), The Late Roman Army in the Near East from Diocletian to the Arab Conquest (Oxford, BAR IS 1717), 313–19.

- FUKS, D., WEISS, E., TEPPER, Y. and BAR-OZ, G. 2016: Seeds of collapse? Reconstructing the ancient agriculture economy at Shivta in the Negev. Antiquity 90(353), 1–5.

- FUKS, D., BAR-OZ, G., TEPPER, Y., ERICKSON-GINI, T., LANGGUT, D., WEISSBORD, L. and WEISS, E. 2020: The Rise and fall of viticulture in the late antique Negev Highlands reconstructed from Archaeobotanical and ceramic data, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(33), 19780–19791.

- GADOT, Y. and TEPPER, Y. 2003: A Late Byzantine Pottery Workshop at Khirbet Baraqa. Tel Aviv 30, 143–48.

- GAZIT, D. 1986: ῌevel ha-Bésor. Tel Aviv (Hebrew).

- GHEITH, H.M. and SULTAN, M.I. 2001: Assessment of the renewable ground water resources of Wadi el Arish, Egypt: modelling, remote sensing and GIS applications. In OWE, M., BRUBAKER, K., RITHCIE, J. and RANGS, A. (eds.), Remote Sensing and Hydrology 2000 (Oxfordshire, Association of Hydrological Sciences Publications 267), 451–54.

- GIBSON, S. 2015: The Archaeology of Agricultural Terraces in the Mediterranean Zone of the Southern Levant and the use of the Optically Stimulated Luminescence Dating Method. In LUCKE, B., BÄUMLER, R., and SCHMIDT, M. (eds.), Soils and Sediments as Archives of Environmental Change. Geoarchaeology and Landscape Change in the Subtropics and Tropics (Erlangen, Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten 42), 295–314.

- GOVRIN, Y. 2007: ῌorvat Qerayot – An early Christian settlement at the desert fringe. In ESHEL, Y. (ed.), The Frontier Desert of Eretz-Israel, Proceedings of the 2nd Annual Meeting, 59–76 (Hebrew).

- GROSSMAN, D. 1994: Expansion and Desertion, the Arab Village and its Offshoots in Ottoman Palestine (Jerusalem) (Hebrew).

- HADDAD, E. and ZWIEBEL, E. 2021: Khirbat Ibreika: archaeological evidence for the retaliation of the Byzantine regime following the Samaritan revolts. Judea and Samaria Studies 30.2(1), 153–88.

- HAIMAN, M. 1995: Agriculture and Nomad-State Relations in the Negev Desert in the Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 279, 5–29.

- HAIMAN, M. 2012: Dating the agricultural terraces in the southern Levantine deserts, the spatial-contextual argument. Journal of Arid Environments 86, 43–49.

- HAIMAN, M. 2018a: The Challenge of Digitized Survey Data. In LEVY, T.E. and JONES, I.W.N. (eds.), Cyber-Archaeology and Grand Narrative (New York), 111–22.

- HAIMAN, M. 2018b: From Palmer to GIS: Two Survey Methods on Trial in the Negev Desert. In GUREVICH, D. and KIDRON, A., Exploring the Holy Land, 150 Years of the Palestine Exploration Fund (Sheffield), 179–98.

- HAIMAN, M. 2020: Between Nessana and Ashkelon: mapping agricultural systems of the 6th–8th Centuries CE. In KLINE, E., SASSON, A. and LEVY-REIFER, A. (eds.), Ashkelon and Its Environs, Studies of the Southern Coastal Plain and the Judean Foothills in Honor of Dr. Nahum Sagiv (Tel Aviv), 229–64. (Hebrew with English summary).

- HAIMAN, M. 2022: Integrating Archaeological Data in Multidisciplinary Environmental Studies – Methodological Notes from High-Resolution Mapping of Ancient Features in Southern Israel. Heritage 2022(5), 1141–1159.

- HAIMAN M., ARGAMAN, E. and STAVI, I. 2020: Ancient runoff harvesting agriculture in the arid Beer Sheva Valley, Israel: an interdisciplinary study, The Holocene 30(8), 196–204.

- HIRSCHFELD, Y. 1989: Horvat ʻAmudei Qerayot. Excavations and Survey in Israel.

- HIRSCHFELD, Y. 2002a: The Desert of the Holy City, The Judean Desert Monasteries in the Byzantine Period (Jerusalem) (Hebrew).

- HIRSCHFELD, Y. 2002b: Deir Qal‘a and the monasteries of western Samaria. In HUMPHREY, J.H. (ed.), The Roman and Byzantine Near East 3 (Portsmouth, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 49, 155–89.

- HIRSCHFELD, Y. 2004: The monasteries of Gaza: an archaeological review. In KOFSKY, A. and BITTON-ASHKELONY, B. (eds.), Christian Gaza in Late Antiquity (Leiden-Boston), 61–88.

- HULL, D. 2008: A Spatial and Morphological Analysis of Monastic Sites in the Northern Limestone Massif. Levant 40, 89–113.

- HUSTER, Y. 2015: Ashkelon 5, The Land Behind Ashkelon (Winona Lake).

- ILAN, Z. 1980: Traces of early agriculture in the region of Katef Beer-Sheva, Nofim 13–14, 27–40 (Hebrew).

- ISRAEL, Y. 1993: Survey of pottery workshops, Naḥal Lakhish - Naḥal Besor, Hadashot Arkheologiyot 100, 91–93.

- ISRAEL, Y. and ERICKSON-GINI, T. 2013: Remains from the Hellenistic through the Byzantine Periods at the 'Third Mile Estate', Ashqelon. 'Atiqot 74, 167–222.

- ISRAEL. Y., SERIY, G. and FEDER, O. 2013: Remains of a Byzantine and Early Islamic Rural Settlement at the Be’er Sheva‘ North Train Station. ‘Atiqot 73, 51*–76* (Hebrew with English summary).

- IZDEBSKI, A., PICKETT, J., ROBERTS, N. and WALISZEWSKI, T. 2016: The environmental, archaeological and historical evidence for Regional climatic changes and their societal impacts in the Eastern Mediterranean in Late Antiquity. Quaternary Science Reviews 136, 189–208.

- KEDAR, Y. 1967: The Ancient Agriculture in the Negev Mountains (Jerusalem) (Hebrew).

- KRAEMER, C.J. 1958: Excavations at Nessana, Vol. III: Non-Literary Papyri (Princeton).

- LENDER, Y. 1990: Archaeological Survey of Israel, Map of Har Nafḥa (196) (Jerusalem).

- MAGEN, Y. 2008a: Oil production in the Land of Israel in the Early Islamic period. In MAGEN, Y. (ed.) (Jerusalem, Judea and Samaria Publications 6), 275–78.

- MAGEN, Y. 2008b: The Samaritans and the Good Samaritans. (Jerusalem, Judea and Samaria Publications 7).

- MAGEN, Y. and AIZIK, N. 2012: A Late Roman Fortress and Byzantine Monastery at Deir Qal'a. In CARMIN, N. (ed.), Christians and Christianity III – Churches and Monasteries in Samaria and Northern Judea (Jerusalem), 107–56.

- MAJCHEREK, G. 1995: Gazan Amphorae: Typology Reconsidered. In MEYZA, H. and MLYNARCZYK, J. (eds.), Hellenistic and Roman Pottery in the Eastern Mediterranean-Advances in Scientific Studies (Warsaw), 163–78.

- MATTINGLY, D. (ed.) 1996: Farming the Desert: The UNESCO Libyan Valleys Archaeological Survey: Volume II: Site Gazetteer and Pottery (London).

- MATTINGLY, D. and DORE, J. 1996: Romano-Libyan Settlement: Typology and Chronology. In BARKER, G. (ed.), Farming the Desert: The UNESCO Libyan Valleys Archaeological Survey: Volume One: Synthesis (London), 111–58.

- MAYERSON, P. 1962: The Ancient Agricultural Regime of Nessana and the Central Negev. In COLT, H.D. (ed.), Excavations at Nessana (Auja Hafir, Palestine), Vol. 1 (London), 224–69.

- MAYERSON, P. 1963: The Desert of Southern Palestine according to Byzantine Sources. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 107: 160–72.

- MAYERSON, P. 1985: The Wine and Vineyards of Gaza in the Byzantine Period. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 257, 75–80.

- MAYERSON, P. 1988: Justinian's Novel 103 and the Reorganization of Palestine, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 269, 65–71.

- MAZOR, G. 1981: The Wine-presses of the Negev. Qadmoniot 53/54, 51–60 (Hebrew).

- NEVO, Y.D. 1991: Pagans and Herders, a Re-examination of the Negev Runoff Cultivation systems in the Byzantine and Early Arab Periods (Sde Boker, Israel).

- NIKOLSKY, V. 2014. Be’er Sheva‘, Railroad Station, Excavations and Surveys in Israel 126. http://hadashot-esi.org.il/Report_Detail_Eng.aspx?id=13667&mag_id=121.

- OKED, S.H. 2001. “Gaza Jar”: A Chronicle, and Economic Overview. In A. Sasson, Z. Safrai and N. Sagiv (eds.), Ashkelon: A City on the Seashore. Ashqelon, 227–250. (Hebrew with English summary).

- PATRICH, J. 1995: The Judean Desert Monasticism in the Byzantine Period: The Institution of Sabas and his Disciples (Jerusalem) (Hebrew).

- ROSEN, A.M. 2007: Civilizing Climate: Social Response to Climate Change in the Ancient Near East (Lanham, MD).

- ROSKIN, J., KATRA I. and BLUMBERG, D.G. 2013: Late Holocene dune mobilizations in the northwestern Negev dunefield, Israel: A response to combined anthropogenic activity and short-term intensified windiness, Quaternary International 303, 10–23.

- RUBIN, R. 1990: The Negev as a Settled Land: Urbanization and Settlement in the Desert in the Byzantine Period. (Jerusalem) (Hebrew).

- SAFRAI, Z. 1997: Settlements in the Shomron Shephela in the Byzantine Period. Judea and Samaria Research Studies 6, 217–34 (Hebrew).

- SHADMAN, A. 2016: The Settlement Pattern of the Rural Landscape between Nahal Rabbah and Nahal Shiloh during the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods (Ph.D. thesis, Bar-Ilan University) (Hebrew with English summary).

- SHADMAN, A. 2019: Rosh Ha-ʻAyin (South and East), Hadashot Arkheologiyot, Excavations and Surveys in Israel 131, 1–31. (Hebrew with English summary). http://hadashot-esi.org.il/Report_Detail_Eng.aspx?id=25525&mag_id=127.

- SHARON, M. 1985: Appendix: Arabic inscriptions from Sede-Boqer – Map 167. In COHEN, R. Archaeological Survey of Israel, Map of Sede-Boqer – West (167), Archaeological Survey of Israel (Jerusalem). 31*–35*.

- SIDI, N., AMIT, D. and AD, U. 2000: Two winepresses from Kefar Sirkin and Mazor, 'Atiqot 44, 254–66.

- SIGL, M., WINSTRUP, M., MCCONNELL, J. R., WELTEN, K. C., PLUNKETT, G., LUDLOW F., BÜNTGEN, U., CAFFEE, M., CHELLMAN, N., DAHL-JENSEN, D., FISCHER, H., KIPFSTUHL, S., KOSTICK, C., MASELLI, O. J., MEKHALDI, F., MULVANEY, R., MUSCHELER, R., PASTERIS, D. R., PILCHER, J. R., SALZER, M., SCHÜPBACH, S., STEFFENSEN, J., P.,. VINTHER, M B., M & WOODRUFF, T. E. 2015: Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years. Nature 523, 543–49.

- SION, O., ASHKENAZI, E. and ERICKSON-GINI, T. 2022: Byzantine 'Avdat and its agricultural hinterland. In GOLANI, A., VARGA, D., TCHEKHANOVETS Y. and BIRKENFELD, M. (eds.), Archaeological Excavations and Research Studies in Southern Israel, 18th Annual Southern Conference, Ben Gurion University and Israel Antiquities Authority (Beer Sheva) (Hebrew).

- SONTAG, F. 2000: Beer Sheva, Ramot. Hadashot Arkheologiyot 111, 91–92.

- SONTAG, F. 2012: Be’er Sheva‘, Hadashot Arkheologiyot 124. http://hadashot-esi.org.il/Report_Detail_Eng.aspx?id=2000&mag_id=119.

- STAVI, I., RAGOLSKY, G., HAIMAN, M. and PORAT, N. 2021: Ancient to recent-past runoff harvesting agriculture in the hyper-arid Arava Valley: dating and insights, The Holocene 31.6, 1047–1054.

- STROUMSA, R. 2008: People and Identities in Nessana (Ph.D. thesis, Duke University).

- TAXEL, I. 2008: Rural monasticism at the foothills of southern Samaria and Judaea in the Byzantine period asceticism, agriculture and pilgrimage. Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 26, 57–73.

- TAXEL, I. 2013: From prosperity to survival: rural monasteries in Palestine in the transition from Byzantine to Muslim rule (seventh century AD). In PRESTON, P.R. (ed.), Mobility, Transition and Change in Prehistory and Classical Antiquity (BAR IS 2534), 145–54.

- TEALL, J.L. 1959: The Grain Supply of the Byzantine Empire, 330–1025. Dumbarton Oaks Papers Vol. 13, 87–139.

- TEPPER, Y., PORAT, N. and BAR-OZ, G. 2020: Sustainable farming in the Roman- Byzantine period: dating an advanced agriculture system near the site of Shivta, Negev desert, Israel, Journal of Arid Environments 177, 1–20.

- URMAN, D. 2004 (ed.): Nessana: Excavations and Studies, Vol. 1 (Beer Sheva, Beer Sheva 17).

- VAN DER VEEN, M., GRANT, A. and BARKER, G. 1996: Romano-Libyan agriculture: crops and animals. In BARKER, G. (ed.), Farming the Desert: The UNESCO Libyan Valleys Archaeological Survey, Vol. 1: Synthesis (London), 227–63.

- YAIR, A. 1987: Environmental effects of loess penetration into the northern Negev desert, Journal of Arid Environments 13, 9–24.

- YAIR, A. 1994: The ambiguous impact of climate change at a desert fringe: northern Negev, Israel. In MILLINGTON, A.C. and PYE, K. (eds.), Environmental.

- Change in Drylands: Biogeographical and Geomorphological Perspectives, (Hoboken, NJ), 199–227.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).