Submitted:

09 July 2024

Posted:

10 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. SDI Readiness Approach

∗ ((At∗Aw ∗(1 − ((1 − As)∗(1 − Ad ) ∗ (1 − Ao)) (1/3))) (1/3)) (1/2)

3.2. Organizational Approach

3.4. Data Collection

- Each survey/interview response was assigned a weight based on the measures specified in Table 2;

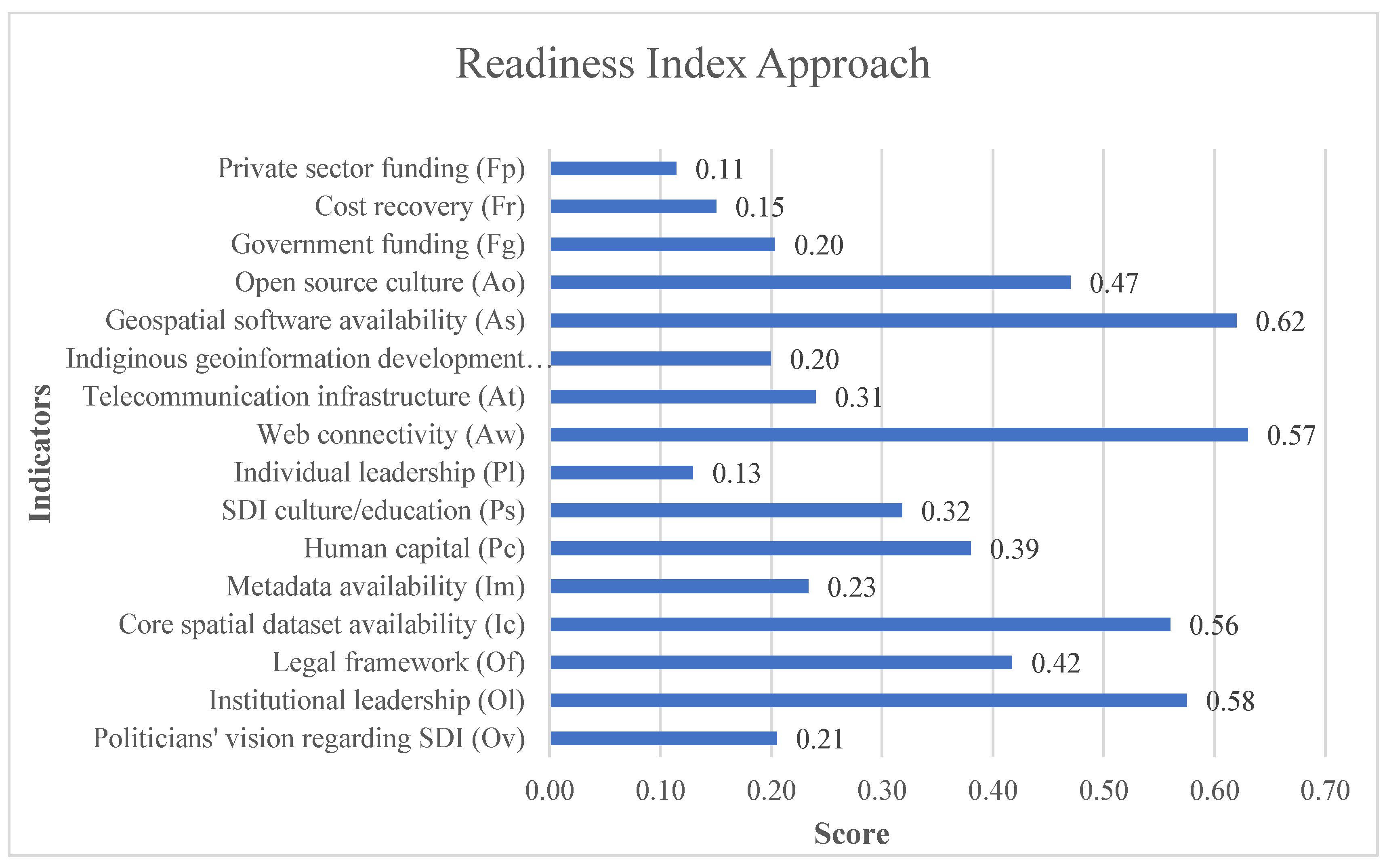

- Values for different SDI readiness factors—such as information infrastructure, technology infrastructure, financial resources, organizational infrastructure, and human resources—were estimated using formulas from the SDI readiness model. The calculated values for these factors represent the geometric mean of scores derived from each factor's specific formula. For instance, the information factor's value was estimated using the formula (Ic ∗I Im) (1/2), where Ic and Im denote criteria scores relating to core spatial dataset availability and metadata availability, respectively.

- For each answer, the overall SDI readiness index was calculated, by computing the geometric mean of the factors.

- Finally, the overall score of Pakistan’s NSDI was the geometrical mean of the indices obtained for response to each question. To make the calculation easy, fast, and accurate, all the involved steps in the calculation were executed using built-in functions of the Microsoft Excel software.

4. Results

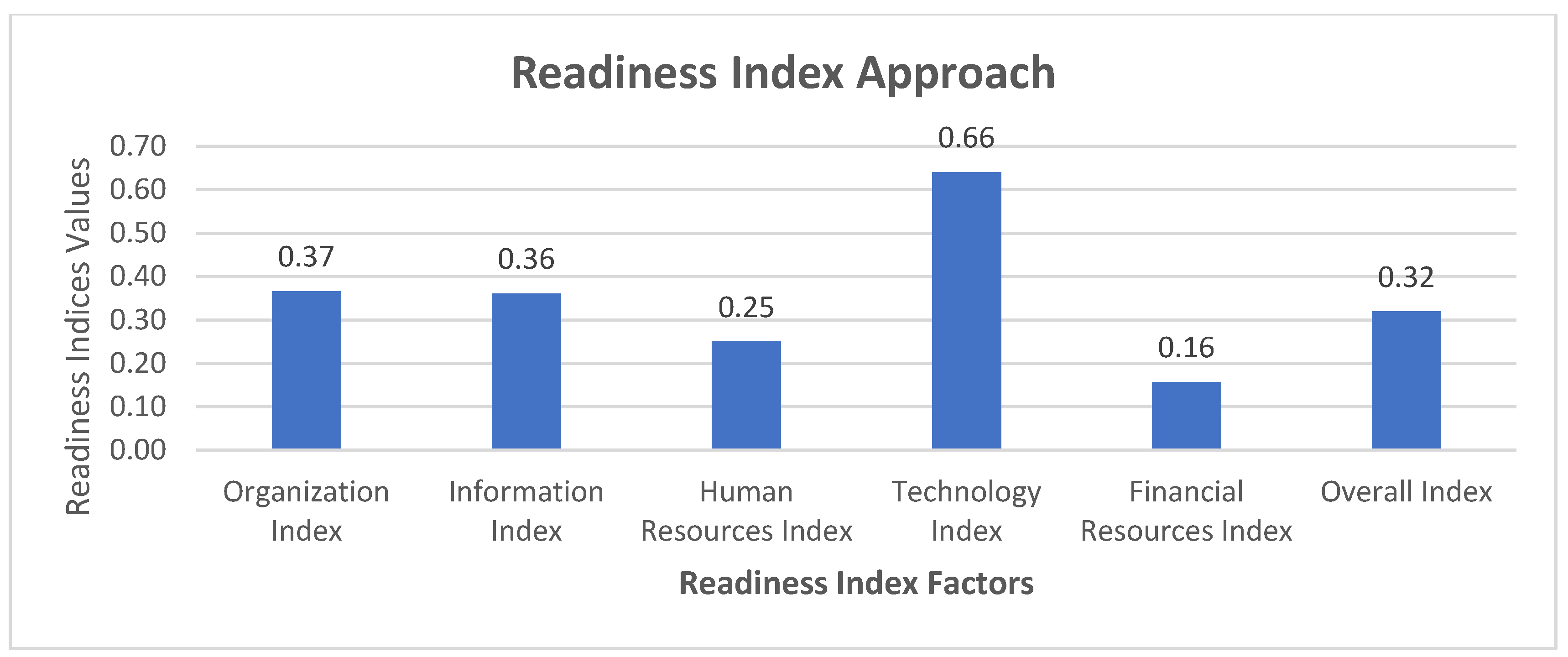

4.1. SDI Readiness Approach

4.1.1. Organization Index

4.1.2. Information Index

4.1.3. Human Resources Index

4.1.4. Technology Index

4.1.5. Financial Index

4.1.6. Overall Index

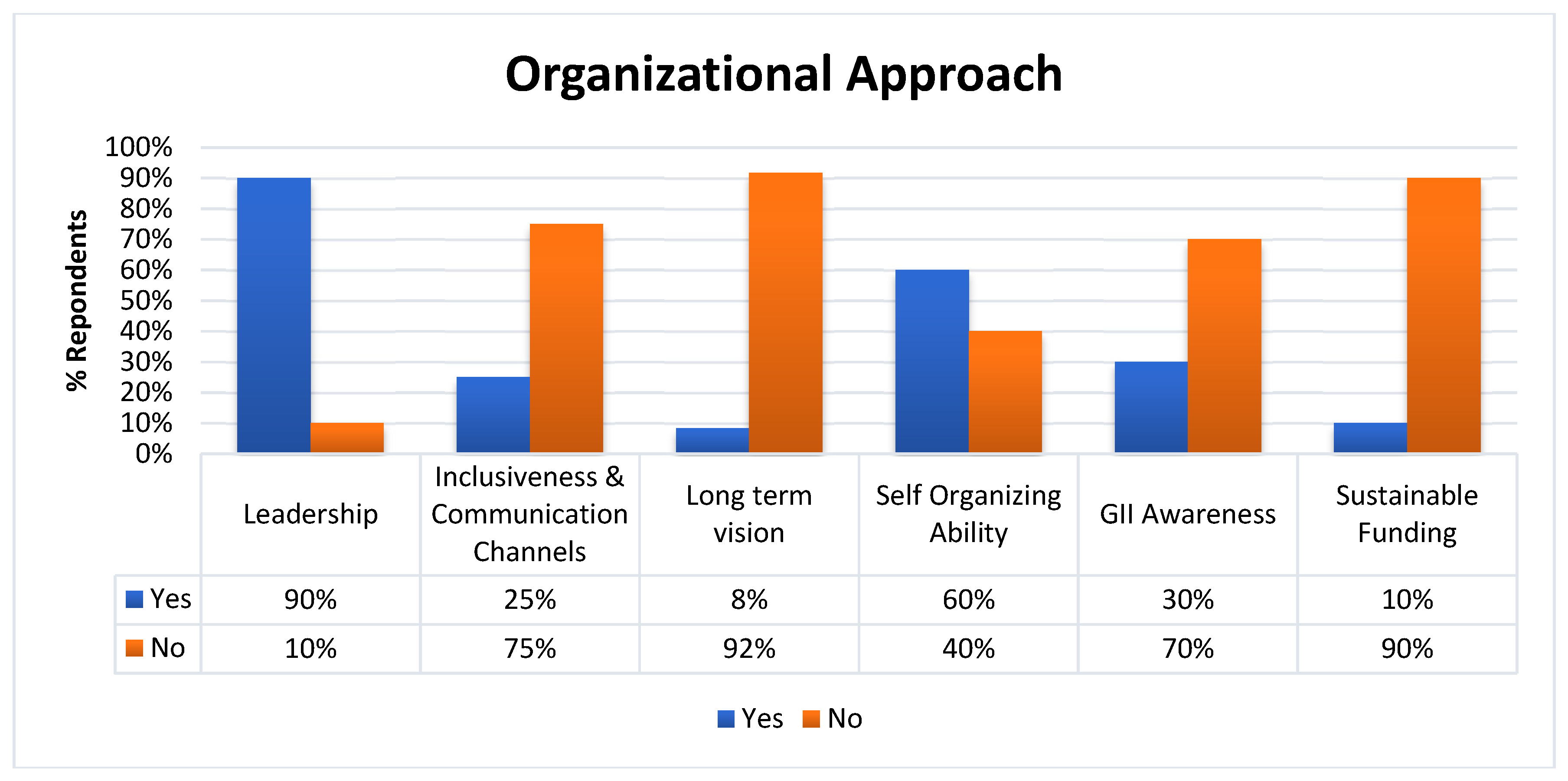

Organizational Approach

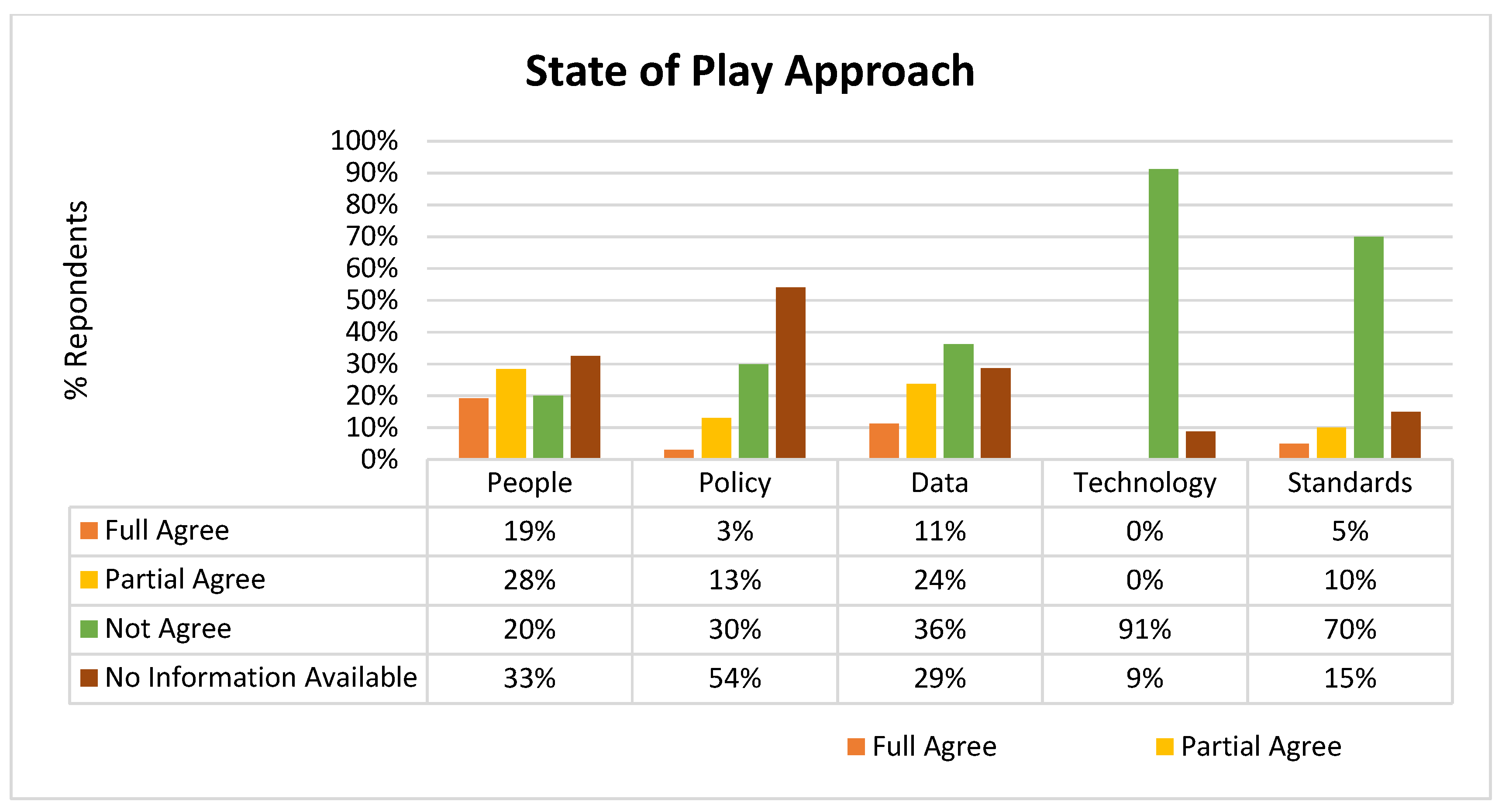

State of Play Approach

5. Discussion

5.1. SDI Readiness Approach

5.2. Organizational Approach

5.3. State of Play Approach

6. Conclusions

- A strong coordination and administrative body be formed for SDI in conjunction with key players in the private and public sectors as is stated in articles 15 of the Surveying and Mapping Act 2014 [43]. This body shall create links with concerned public and private sector bodies and seek changes to the regulatory procedure having crucial considerations for the national spatial development.

- Promotion of awareness programs about the benefits of NSDI among politicians, the government, and the private sector for the sake of creating supporters and ensuring suitable comprehension of NSDI.

- Establish common guidelines, standards, and techniques to make the deployment of NSDI effective, thus the systems and devices in different platforms will be consistent and interoperable.

- Promotion of private-sector involvement such as public-private partnerships (PPP) [44] or other suitable instruments, which can employ private-sector problem-solving abilities and resources to speed up progress.

- Setting up stable financial resources for NSDI because of providing geospatial data necessary for the continuity of important projects including NSDI initiatives. Projects like the formation of a new geodetic datum by the country and a couple of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) projects can be attached to supplement the progress of NSDI development in Pakistan.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN-GGIM Virtual Regional Seminar on Operationalizing the Integrated Geospatial Information Framework in Asia and the Pacific 2020, 1–6.

- Williamson, I. National SDI Initiatives. In Developing Spatial Data Infrastructures; 2003.

- Diaz, L.; Remke, A.; Kauppinen, T.; Degbelo, A.; Foerster, T.; Stasch, C.; Rieke, M.; Schaeffer, B.; Baranski, B.; Bröring, A.; et al. Future SDI - Impulses from Geoinformatics Research and IT Trends. International Journal of Spatial Data Infrastructures Research 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetl, V.; Ivić, S.M.; Tomić, H. Improvement of National Spatial Data Infrastructure as a Public Project of Permanent Character. Kartografija i Geoinformacije 2009, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Piyasena, N.M.P.M.; Vithanage, P.A.D.V.; Witharana, S.L. A Review of Sri Lanka’s National Spatial Data Infrastructure (SL-NSDI) with the Aim of Enhancing Its Functionalities. In Geospatial Science for Smart Land Management: An Asian Context; 2023.

- Ngereja, Z.R. The Need for Spatial Data Infrastructure for Sustainable Development in Tanzania. African Journal of Land Policy and Geospatial Sciences 2021, 4, 718–729. [Google Scholar]

- Efendyan, P.; Petrosyan, M. Legal Aspects of National Spatial Data Infrastructure of Republic of Armenia. Modern Achievements of Geodesic Science and Industry 2023, 1, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izdebski, W.; Zwirowicz-Rutkowska, A.; Nowak da Costa, J. Open Data in Spatial Data Infrastructure: The Practices and Experiences of Poland. Int J Digit Earth 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitis, M.; Kopsachilis, V.; Tataris, G.; Michalakis, V.I.; Pavlogeorgatos, G. The Development of a Spatial Data Infrastructure to Support Marine Spatial Planning in Greece. Ocean Coast Manag 2022, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C. V.; Rifai, H.S. Development and Assessment of a Web-Based National Spatial Data Infrastructure for Nature-Based Solutions and Their Social, Hydrological, Ecological, and Environmental Co-Benefits. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmal Ali and Munir Ahmad Geospatial Data Sharing in Pakistan: Possibilities and Problems. In Proceedings of the GSDI 14 world conference; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2013.

- Ali, A. Assessing Readiness for National Geospatial Data Clearinghouse-A Milestone for Sdi Development in Pakistan. In Proceedings of the ICAST 2008: Proceedings of 2nd International Conference on Advances in Space Technologies - Space in the Service of Mankind; 2008; pp. 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Imran, M.; Jabeen, M.; Ali, Z.; Mahmood, S.A. Factors Influencing Integrated Information Management: Spatial Data Infrastructure in Pakistan. Information Development 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Khayal, M.S.H.; Tahir, A. Analysis of Factors Affecting Adoption of Volunteered Geographic Information in the Context of National Spatial Data Infrastructure. ISPRS Int J Geoinf 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Ali, A.; Mobo, F.D.; Hussain, H. Spatial Data Infrastructure for Information Governance: The Case Study From Pakistan. In Creating and Sustaining an Information Governance Program; Helge, K., Rookey, C.A., Eds.; IGI Global, 2024; pp. 203–216 ISBN 9798369304747.

- Ahmad, M.; Ali, A. A Review of Governance Frameworks for National Spatial Data Infrastructure. In Innovation, Strategy, and Transformation Frameworks for the Modern Enterprise; Correia, A., B. Agua, P., Eds.; IGI Global, 2023; pp. 186–207 ISBN 9798369304594.

- Ali, A.; Imran, M. National Spatial Data Infrastructure vs. Cadastre System for Economic Development: Evidence from Pakistan. Land (Basel) 2021, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Ahmad, M.; Nawaz, M.; Sattar, F. Spatial Data Infrastructure as the Means to Assemble Geographic Information Necessary for Effective Agricultural Policies in Pakistan. Information Development 2024, 02666669241244503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giff, G.; Jackson, J. Towards An Online Self-Assessment Methodology for SDIs. In Spatial Enablement in Support of Economic Development and Poverty Reduction; 2013.

- Grus, L.; Crompvoets, J.; Bregt, A.; van Loenen, B.; Fernandez, T.D. Applying the Multi-View Spatial Data Infrastructure Assessment Framework in Several American Countries and The Netherlands. In A Multi-View Framework to Assess SDIs; 2008 ISBN 978-0-7325-1623-9.

- Grus, Ł. Assessing Spatial Data Infrastructures, Delft, the Netherlands: NCG, 2010.

- Coleman, D.J.; Nebert, D.D. Building a North American Spatial Data Infrastructure. Cartogr Geogr Inf Sci 1998, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, J.; Nichols, S. Developing a National Spatial Data Infrastructure. Journal of Surveying Engineering 1994, 120, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Fernández, T.; Fernández, M.D.; Andrade, R.E. The Spatial Data Infrastructure Readiness Model and Its Worldwide Application. A Multi-View Framework to Assess SDIs, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, T.D.; Crompvoets, J. Evaluating Spatial Data Infrastructures in the Caribbean for Sustainable Development. GSDI-10 Conference, Small Island Perspectives on Global Challenges: The role of Spatial data in supporting a sustainable future, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke, D.; Zambon, M.; Crompvoets, J.; Dufourmont, H. INSPIRE Directive: Specific Requirements to Monitor Its Implementation. In A Multi-view Framework to Assess Spatial Data Infrastructures; 2008 ISBN 978-0-7325-1623-9.

- Crompvoets, J. National Spatial Data Clearinghouses, Worldwide Development and Impact, Wageningen University, the Netherlands., 2006.

- Nushi, B.; Loenen, B. van; Besemer, J.; Crompvoets, J. Multi-View SDI Assessment of Kosovo (2007-2010) - Developing a Solid Base to Support SDI Strategy Development. In Spatially Enabling Government, Industry and Citizens - Research and Development Perspectives; 2012.

- Kok, B.; van Loenen, B. How to Assess the Success of National Spatial Data Infrastructures? Comput Environ Urban Syst 2005, 29, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeda, D. Assessing the Development of Ethiopian National Spatial Data Infrastructure, Wageningen University, 2012.

- Pinsonnault, R. Toward a User-Centric Peru Spatial Data Infrastructure Based on Free and Open Source Software, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, the Netherlands., 2013.

- Okuku, J.; Grus, L. Assessing the Development of Kenya National Spatial Data Infrastructure (KNSDI). South African Journal of Geomatics 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mwange, C.; Mulaku, G.C.; Siriba, D.N. Reviewing the Status of National Spatial Data Infrastructures in Africa. Survey Review 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari Oskouei, A.; Modiri, M.; Alesheikh, A.; Hosnavi, R.; Nekooie, M.A. An Analysis of the National Spatial Data Infrastructure of Iran. Survey Review 2019, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbiyi, J. Reviewing the Status of National Spatial Data Infrastructure: A Case Study in Southern African Countries, Wien, 2021.

- Rahman, Md.M.; Szabó, G. Assessing the Status of National Spatial Data Infrastructure (NSDI) of Bangladesh. ISPRS Int J Geoinf 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eelderink, L.; Crompvoets, J.; de Man, E. Towards Key Variables to Assess National Spatial Data Infrastructures (NSDIs) in Developing Countries. A Multi-View Framework to Assess SDIs, 2008, 307–325.

- Delgado-Fernández, T.; Lance, K.; Buck, M.; Onsrud, H. Assessing an SDI Readiness Index. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week and GSDI-8; 2005; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Grus, L.; Crompvoets, J.; Bregt, A.; van Loenen, B.; Fernandez, T.D. Applying the Multi-View Spatial Data Infrastructure Assessment Framework in Several American Countries and The Netherlands. In A Multi-View Framework to Assess SDIs; 2008 ISBN 978-0-7325-1623-9.

- Mohammadi, H.; Associate Professor, A.R. The Integration of Multi-Source Spatial Datasets in the Context of SDI Initiatives. Department of Geomatics, School of Engineering, Centre for SDI and Land Administration, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, K.; Professor Iams Williamson and Dr, A.R. A Local-State Government Spatial Data Sharing Partnership Model to Facilitate SDI Development. Department of Geomatics, School of Engineering, Centre for SDI and Land Administration, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- de Man, E. Spatial Data Infrastructuring: Praxis between Dilemmas. International Journal of Spatial Data Infrastructures Research 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GoP Surveying and Mapping Act; National Assembly of Pakistan: Islamabad, 2014.

- Asmat, A. Potential of Public-Private Partnership for NSDI Implementation in Pakistan, MSc Thesis, ITC: Enschede, Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Crompvoets, J.; Rajabifard, A.; van Loenen, B.; Delgado Fernández, T. A Multi-View Framework to Assess SDIs, 2008.

| Factors | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Organizational Infrastructure | A vision of politicians about SDI (Ov) |

| Institutional leadership (Ol) | |

| Legal framework (Of) | |

| Information Infrastructure | Availability of core spatial datasets (Ic) |

| Availability of metadata (Im) | |

| Human Resources | Human capital (Pc) |

| Culture/education regarding SDI (Ps) | |

| Individual leadership (Pl) | |

| Technology Infrastructure | Web connectivity (Aw) |

| Telecommunication infrastructure (At) | |

| Indigenous development of geospatial software (Ad) | |

| Availability of commercial geospatial software (As) | |

| Culture regarding the use of open-source GI software (Ao) | |

| Government-level funding (Fg) | |

| Financial Resources | Mechanism of cost recovery (Fr) |

| Funding from private sector (Fp) |

| Options | Weights |

|---|---|

| Extremely high | 0.99 |

| Very high | 0.80 |

| High | 0.65 |

| Medium | 0.50 |

| Low | 0.35 |

| Very low | 0.20 |

| Extremely low | 0.01 |

| Indicators | Sub-Indicators |

|---|---|

| Leadership | ∙ Does the Government of Pakistan establish Pakistan’s NSDI leadership? ∙ Do need to establish Pakistan’s NSDI is formally supported by the relevant laws or acts or regulations. |

| Inclusiveness & Communication Channels |

∙ Are participants actively participating in the process of establishing SDI at the national or local level? ∙ Does there exist a commitment platform to support and facilitate the journey of establishing Pakistan’s NSDI? |

| Long Term Vision | ∙ Presence of a strategic plan to establish NSDI for is acceptable to all stakeholders? ∙ Are private sector organizations aligned with the development plan of Pakistan’s NSDI? ∙ Most of the organizations are aligned with the strategic plan of Pakistan’s NSDI. |

| Self-Organizing Ability | ∙ SDI community addresses problems in society that may need the availability of relevant geospatial data. Does Pakistan’s NSDI do the same? ∙ Do the level of capacity building and awareness campaigns of Pakistan’s NSDI can influence the societal dynamics? |

| GI Awareness | ∙ Does Pakistan’s NSDI initiative launch an awareness campaign among the citizens to raise the importance of NSDI? ∙ Does Pakistan’s NSDI initiative have an awareness campaign among the private sector and academia? |

| Sustainable Funding | Does Pakistan’s NSDI initiative have sustainable funding? |

| Indicators | Sub-Indicators |

|---|---|

| People | ∙ SDI initiatives being executed in the country are truly national. ∙ One or more components of the SDI architecture have gained a certain level of maturity at the operational level. ∙ The national-level GI association is part of the process of coordination for the establishment of the NSDI initiative. ∙ Only public sector organizations are engaged in the NSDI development. ∙ Enough qualified manpower is available to implement SDI initiatives in the country. ∙ Involvement of spatial data producers & users in the process of the establishment of NSDI. |

| Policy | ∙ True Public-Private Partnerships are available to support and facilitate the initialization, development & commissioning of NSDI-related projects. ∙ There is a "Right of Access to Information Act" which covers legislation about the protection of Geo-Information. ∙ Privacy laws are actively in place by the stakeholders of NSDI. ∙ There is a pricing policy that exists for GI trading. ∙ Existence of relevant framework, guideline, act, law, rules, or policy for spatial data sharing. |

| Data | ∙ All the applicable geodetic reference systems and projection systems are standardized, organized, documented, and interoperable. ∙ Spatial datasets are available for most of the domain areas. ∙ Metadata of reference data & core thematic data is produced at a significant level. ∙ Data quality control procedures and guidelines applicable to NSDI are available in organized and documented form. |

| Technology | ∙ Online access services for metadata are available for one or more organizations. |

| ∙ Online service to download core spatial datasets is available at the national level. | |

| ∙ An online web mapping service is available for the core spatial set at the national level. | |

| ∙ One or more standardized metadata catalogues are available for one or more organizations. | |

| Standards | ∙ All the SDI initiatives paid special attention to issues regarding standards. ∙ The process of data collection is properly standardized for all data collection drives. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).