Submitted:

08 July 2024

Posted:

10 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Motivation

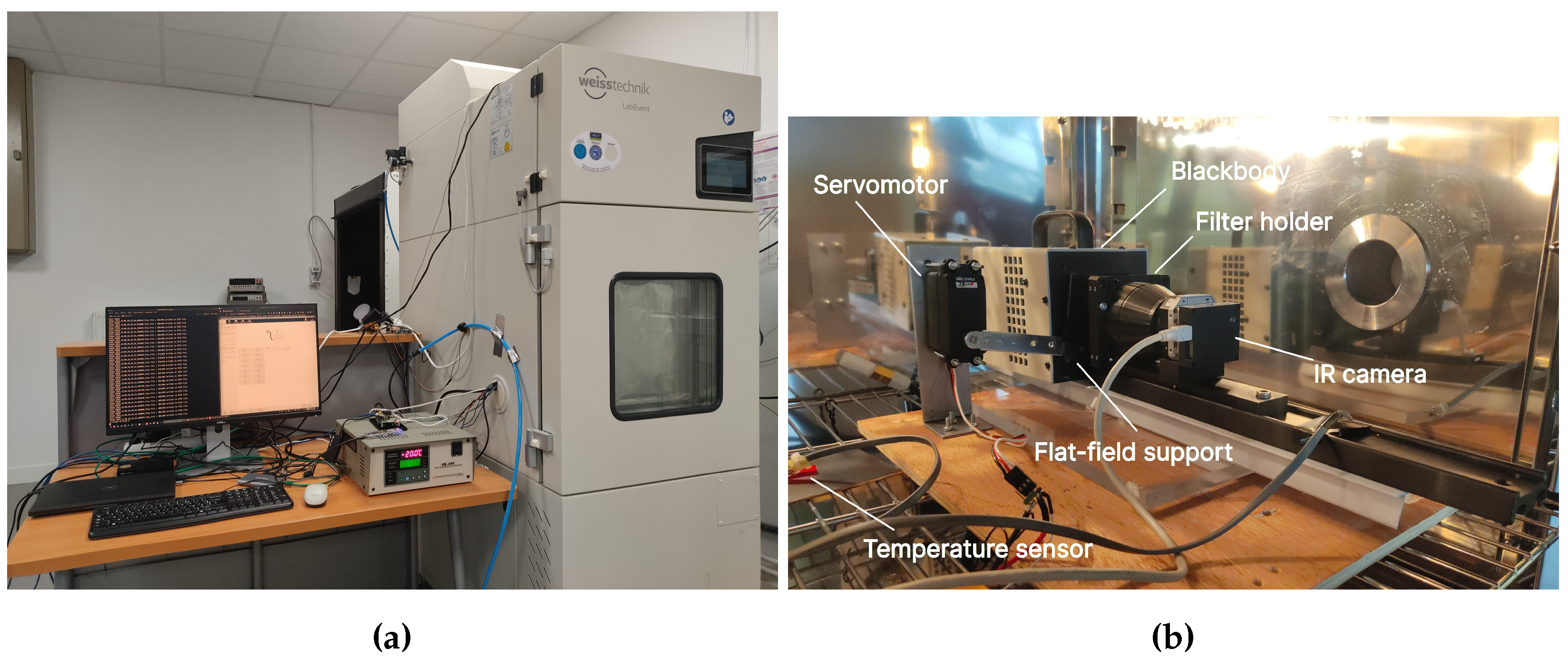

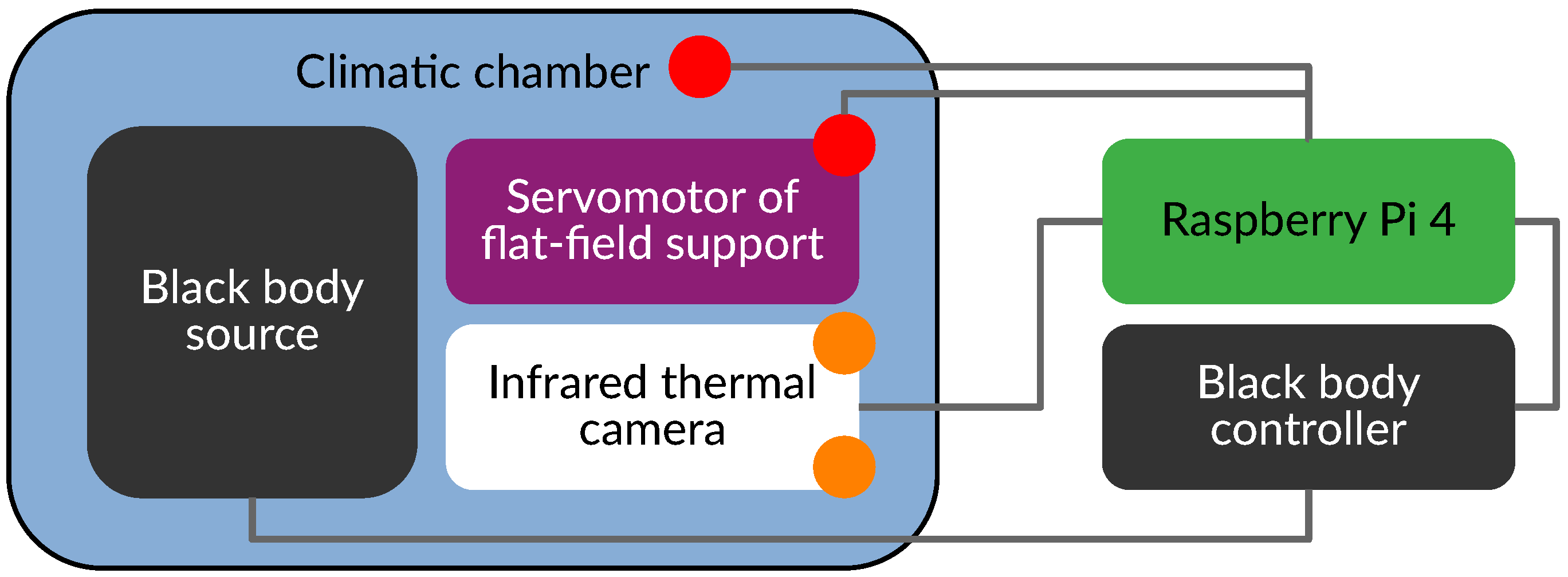

2.2. Experimental Setup

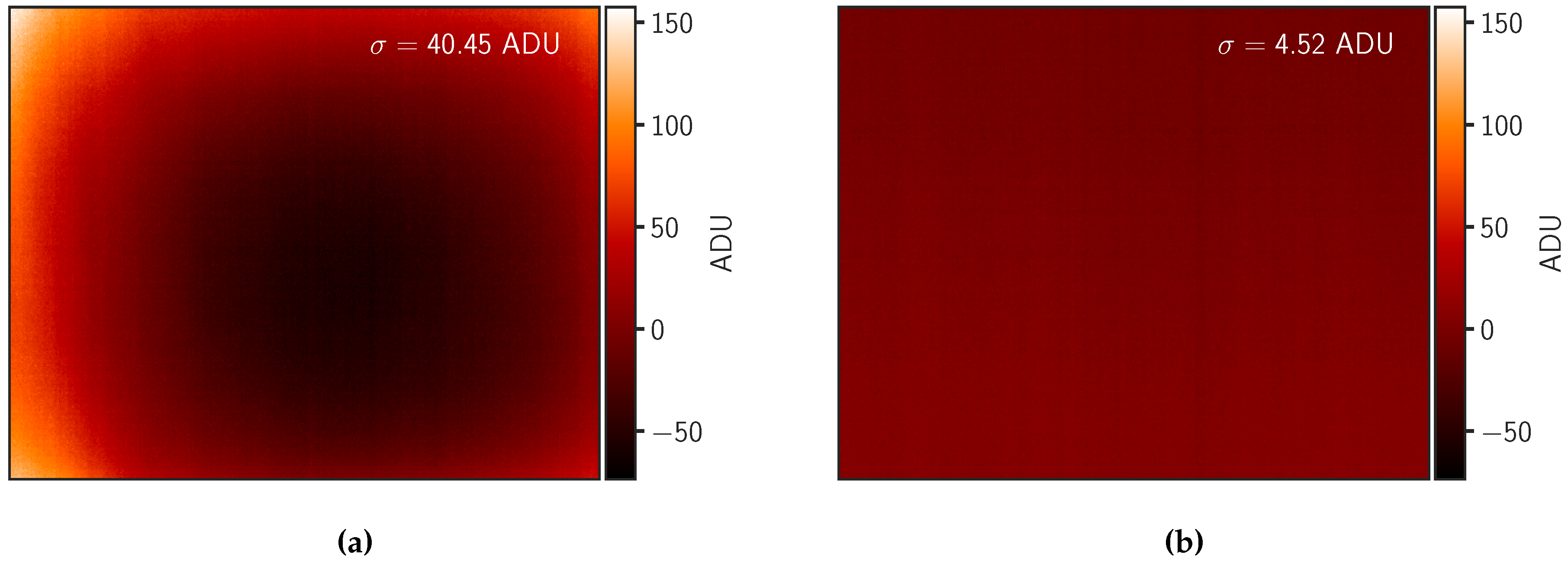

2.3. Improved In-Situ Non-Uniformity Correction

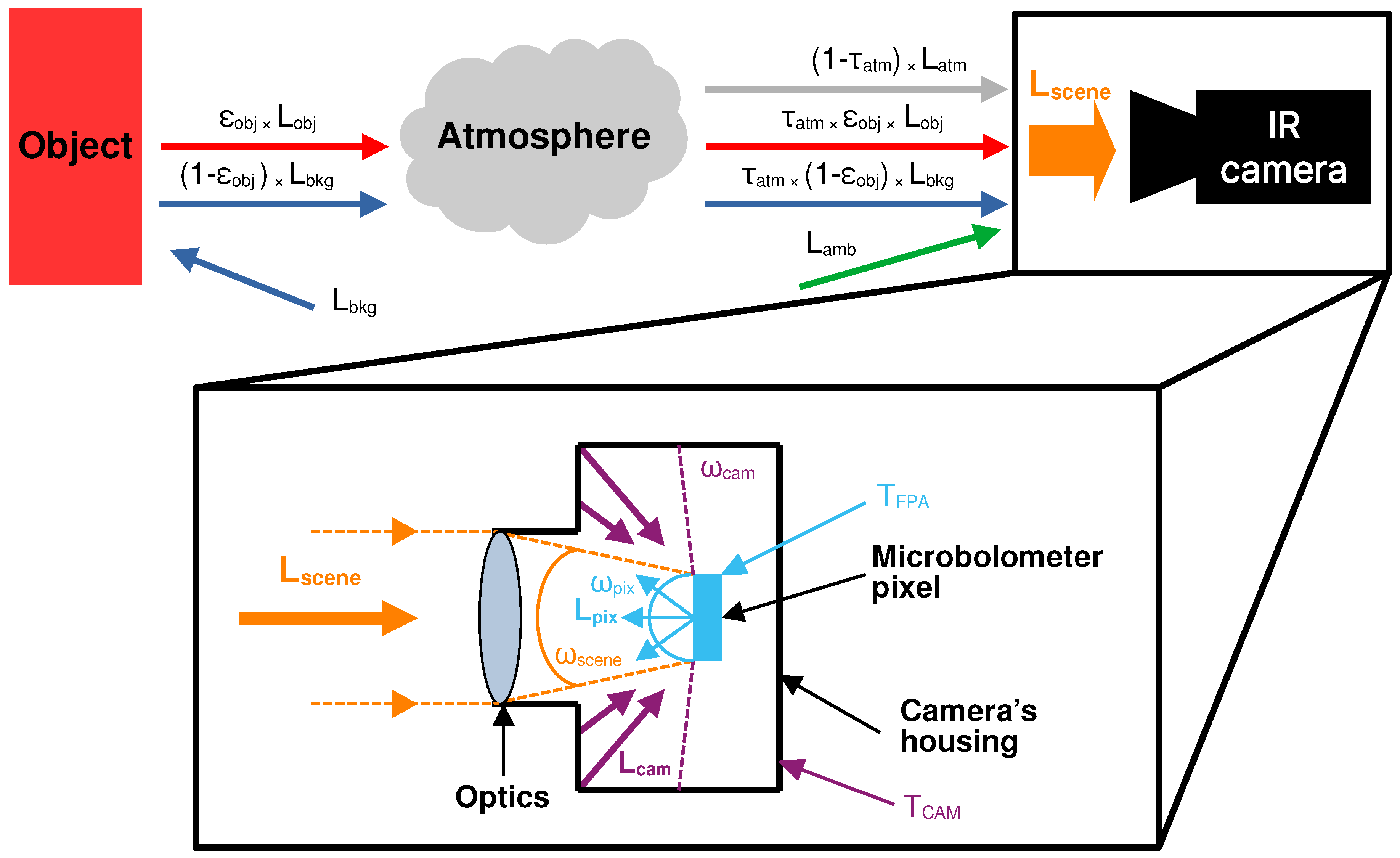

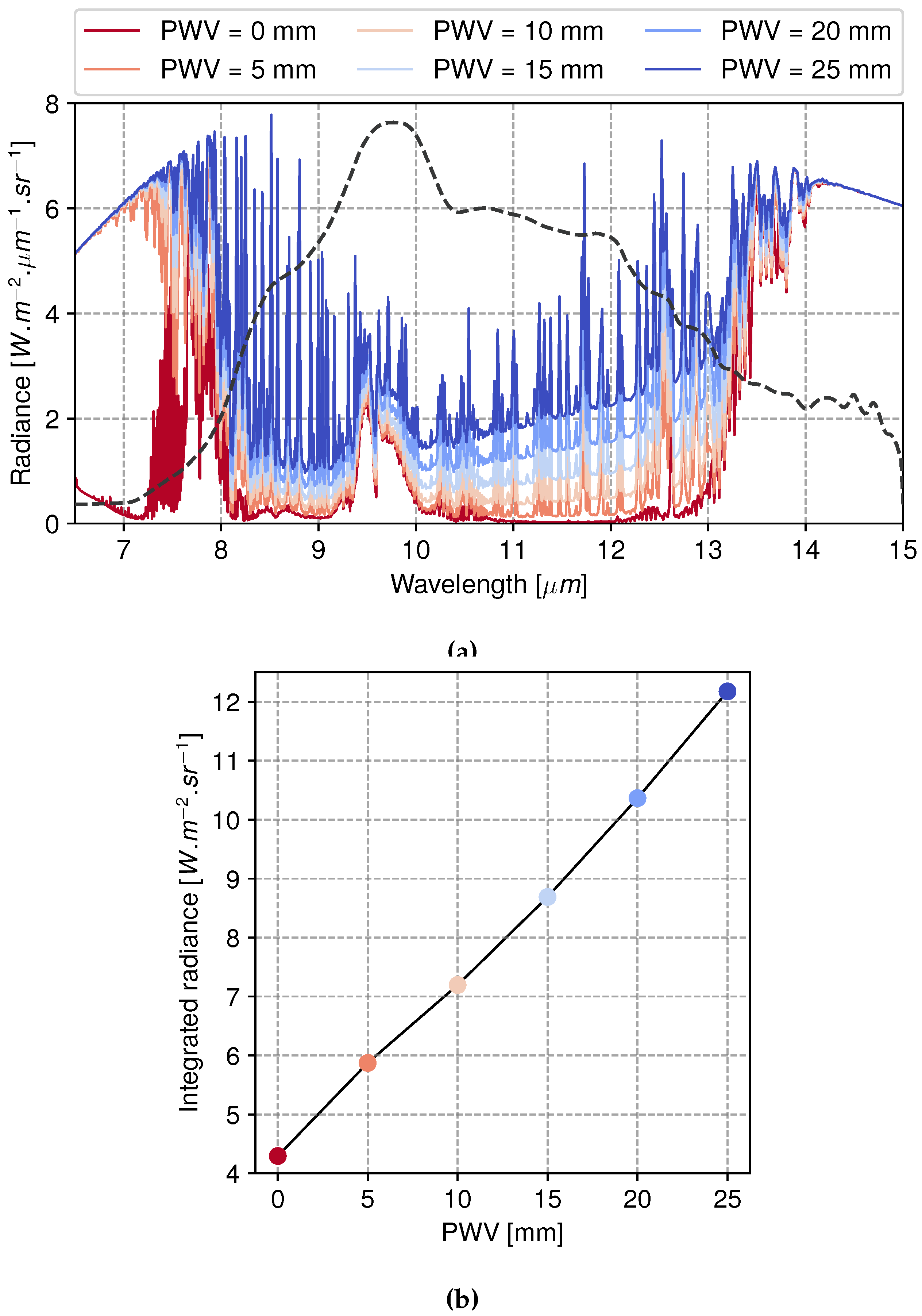

2.4. Generic Scene Radiance Model

2.5. Close-Up Views Radiance Model

2.6. Thermal Interactions Inside the Camera

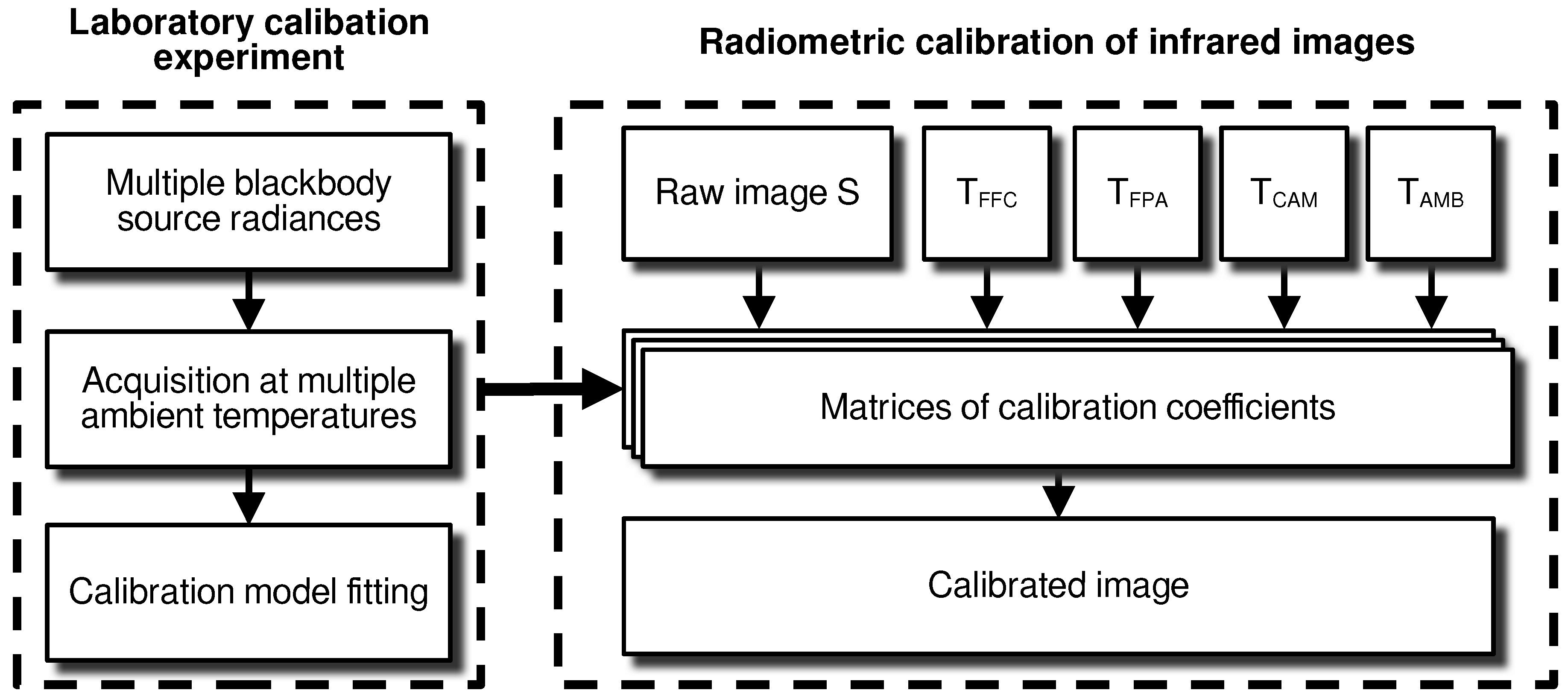

2.7. Calibration Model

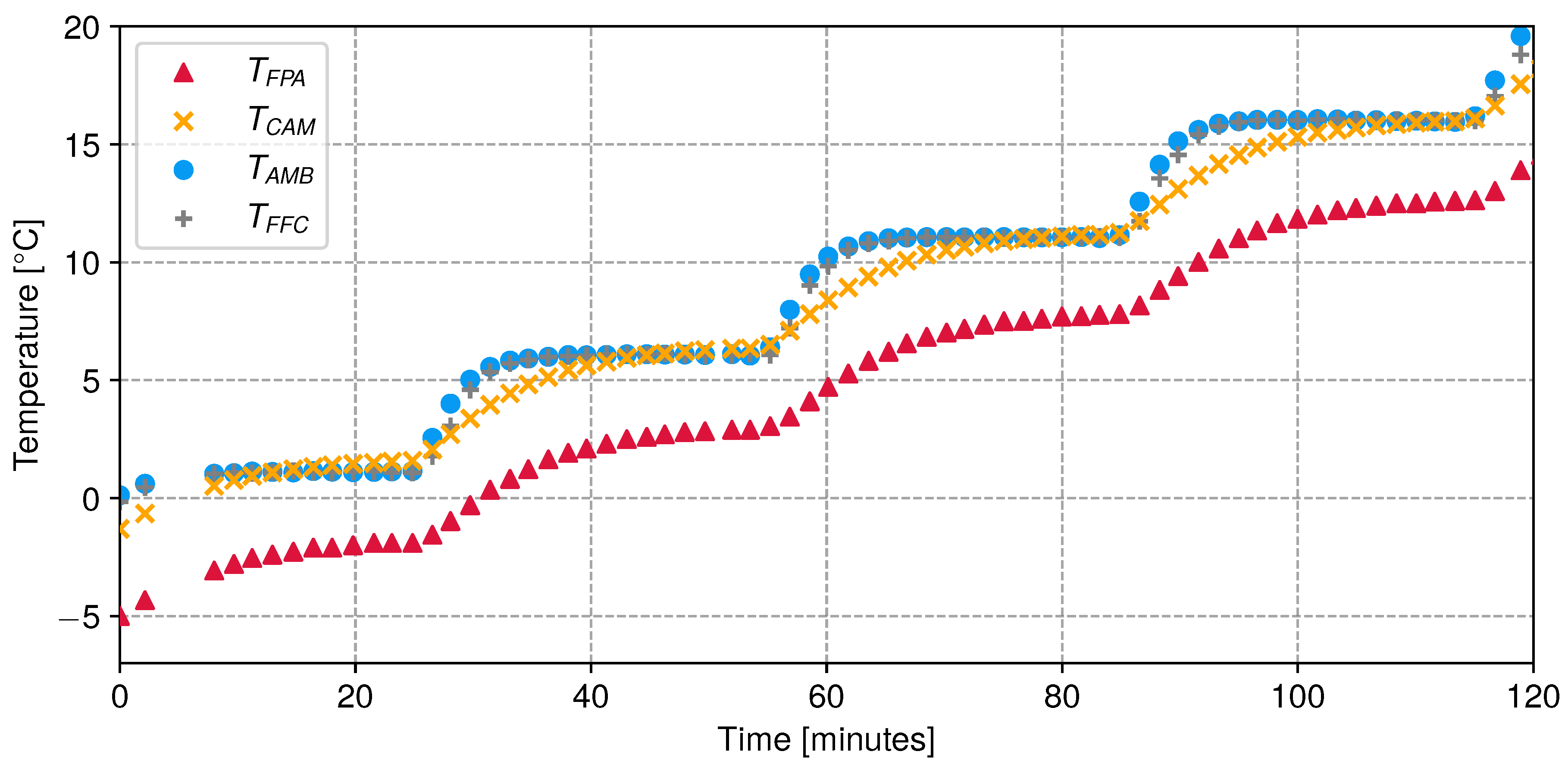

2.8. Acquisition Procedure and Dataset

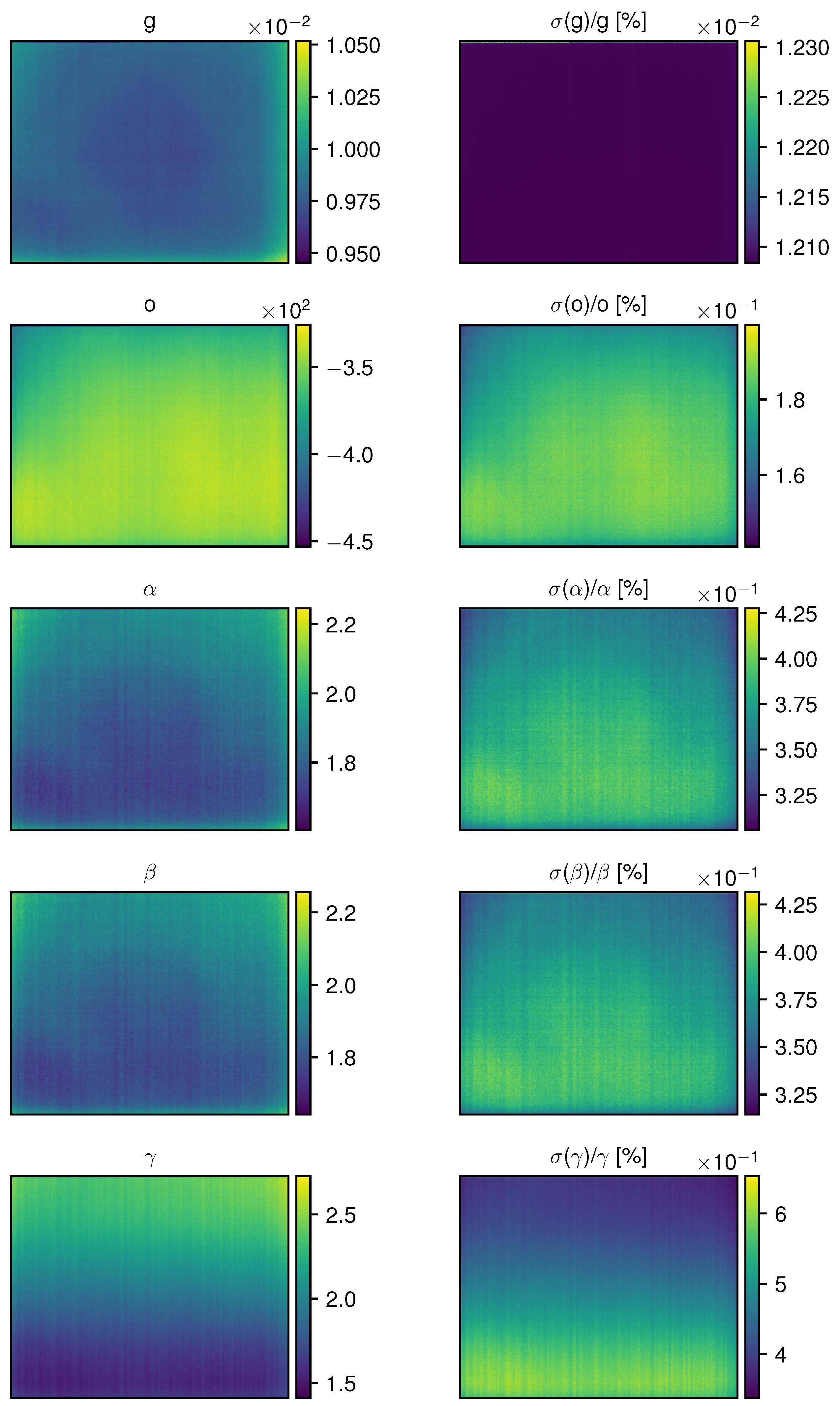

2.9. Data Fitting

3. Results

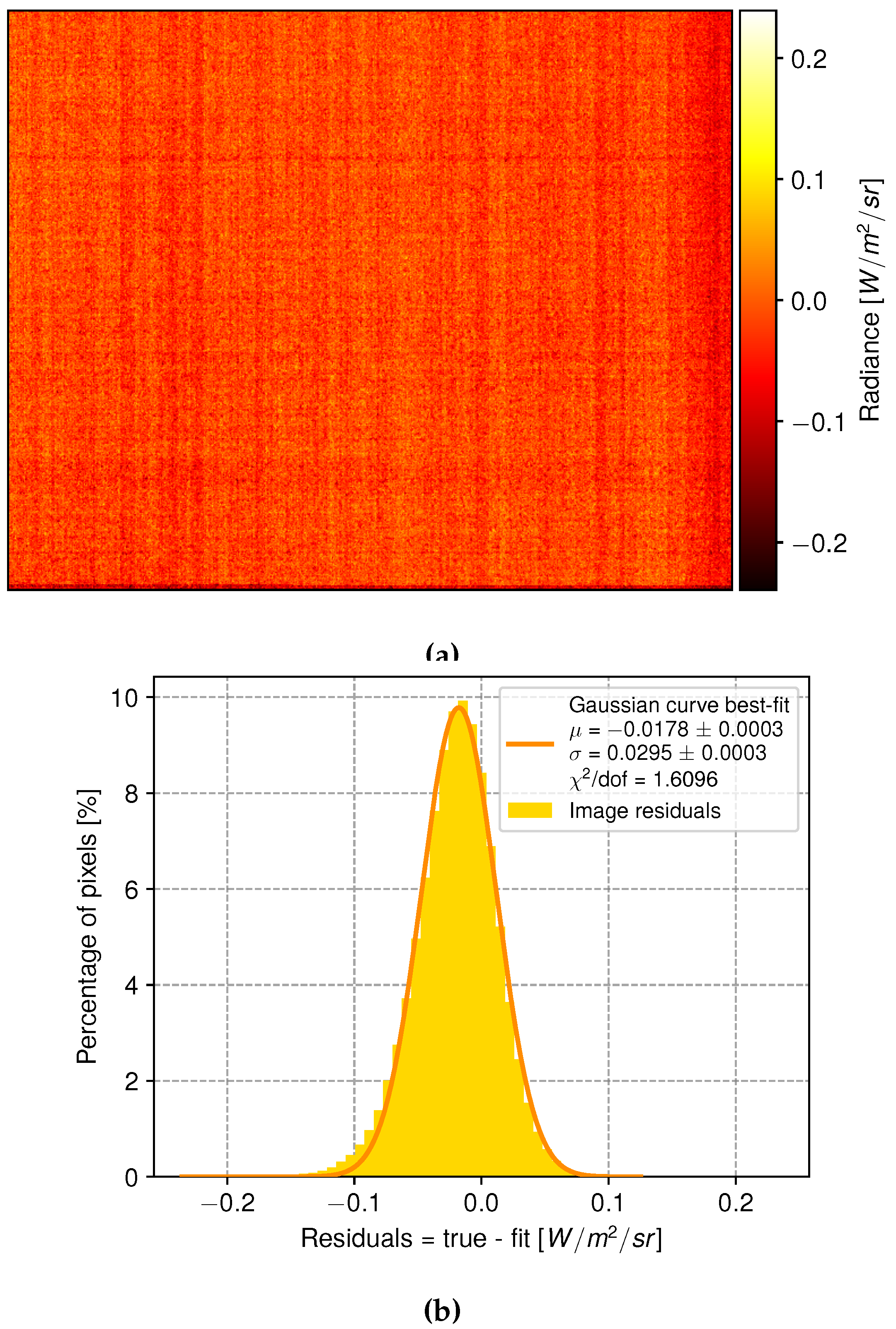

3.1. Flat-Field Correction

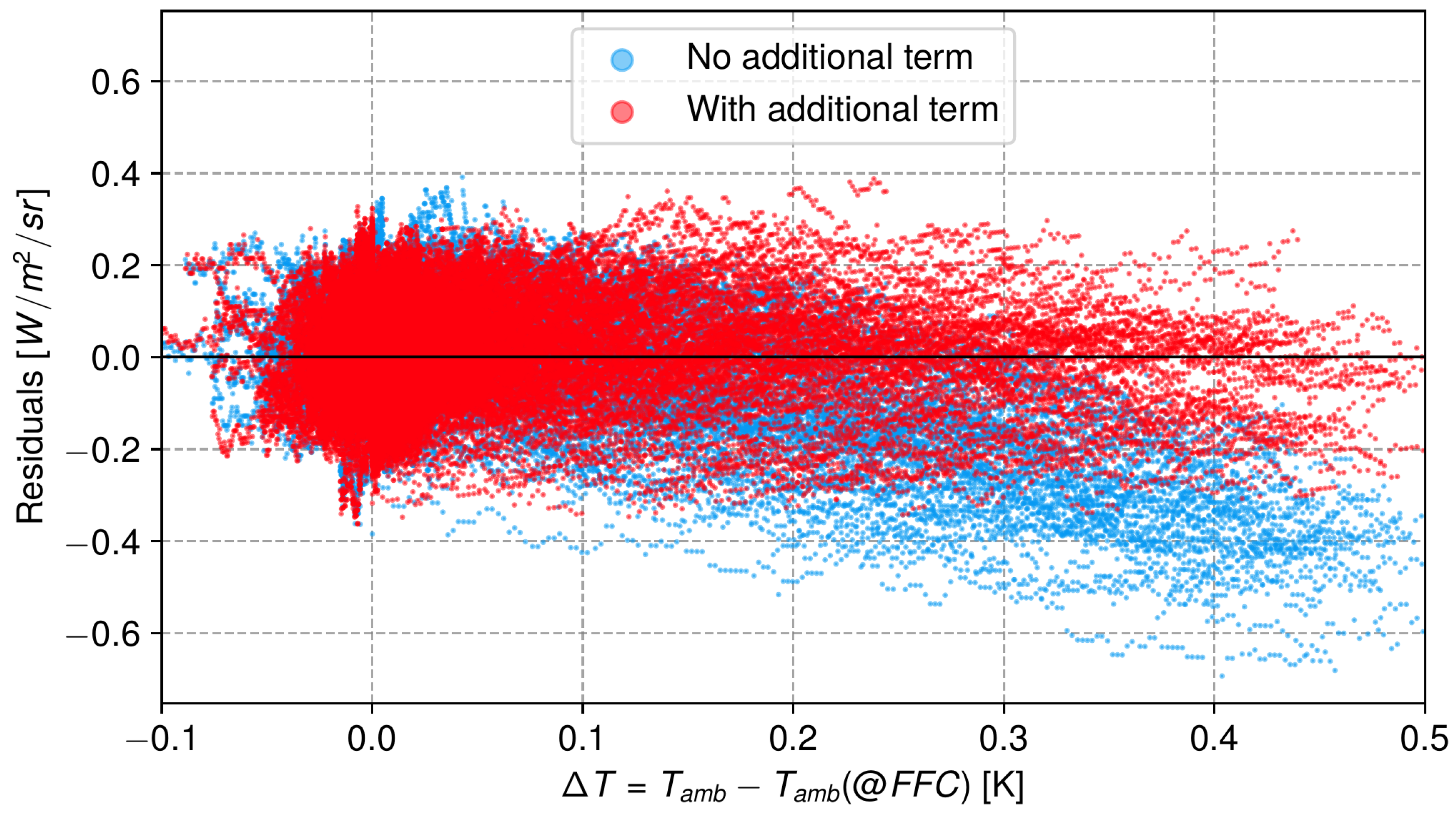

3.2. Calibration Fit

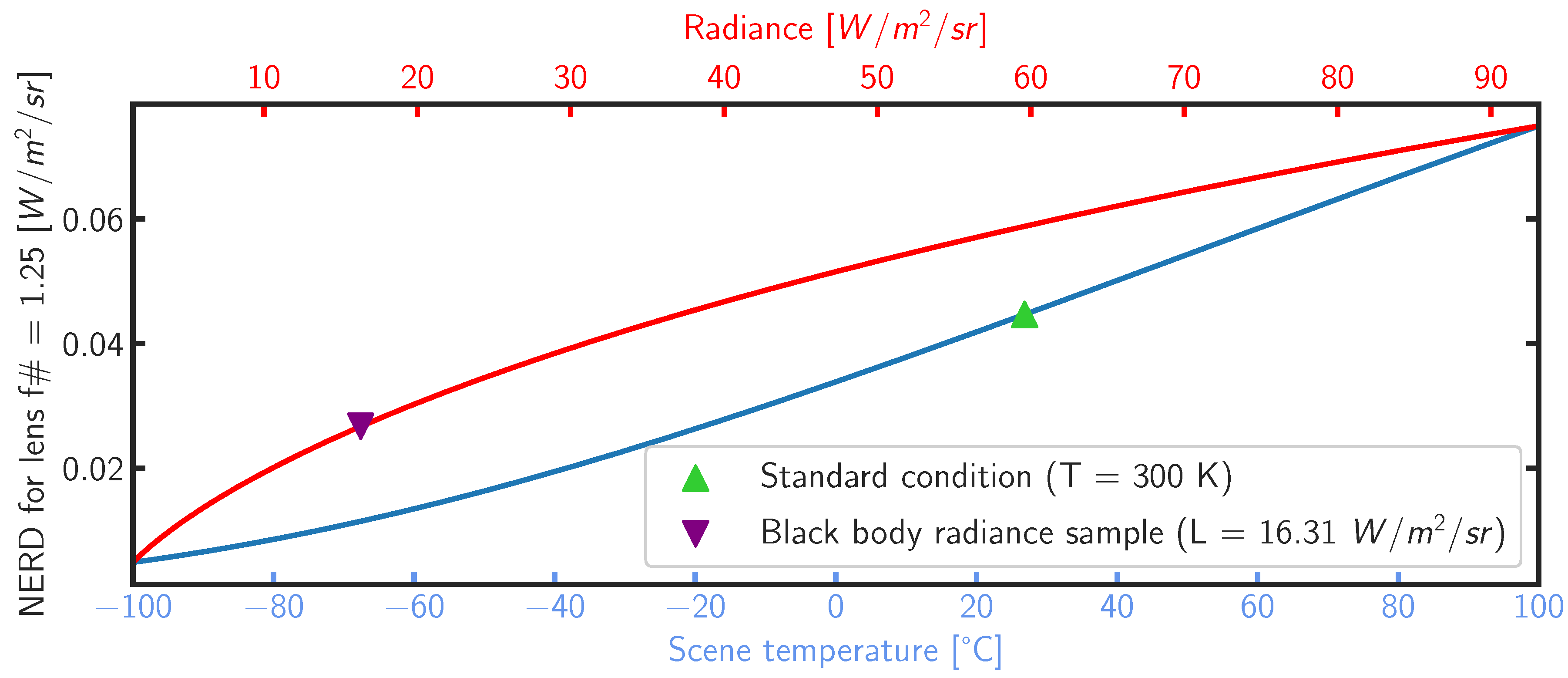

3.3. Spatial Noise

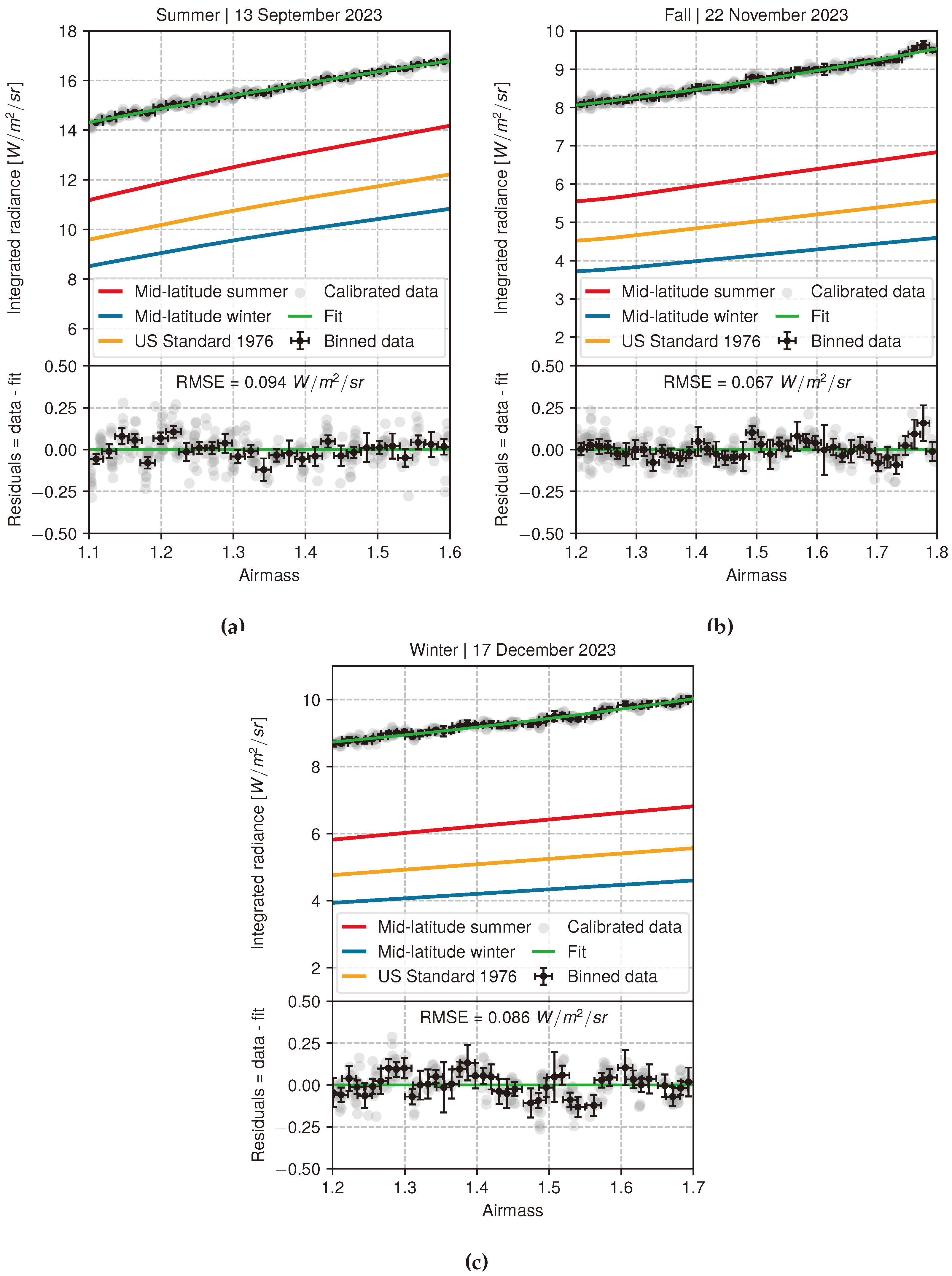

3.4. Application to Sky Radiance Images

4. Discussion

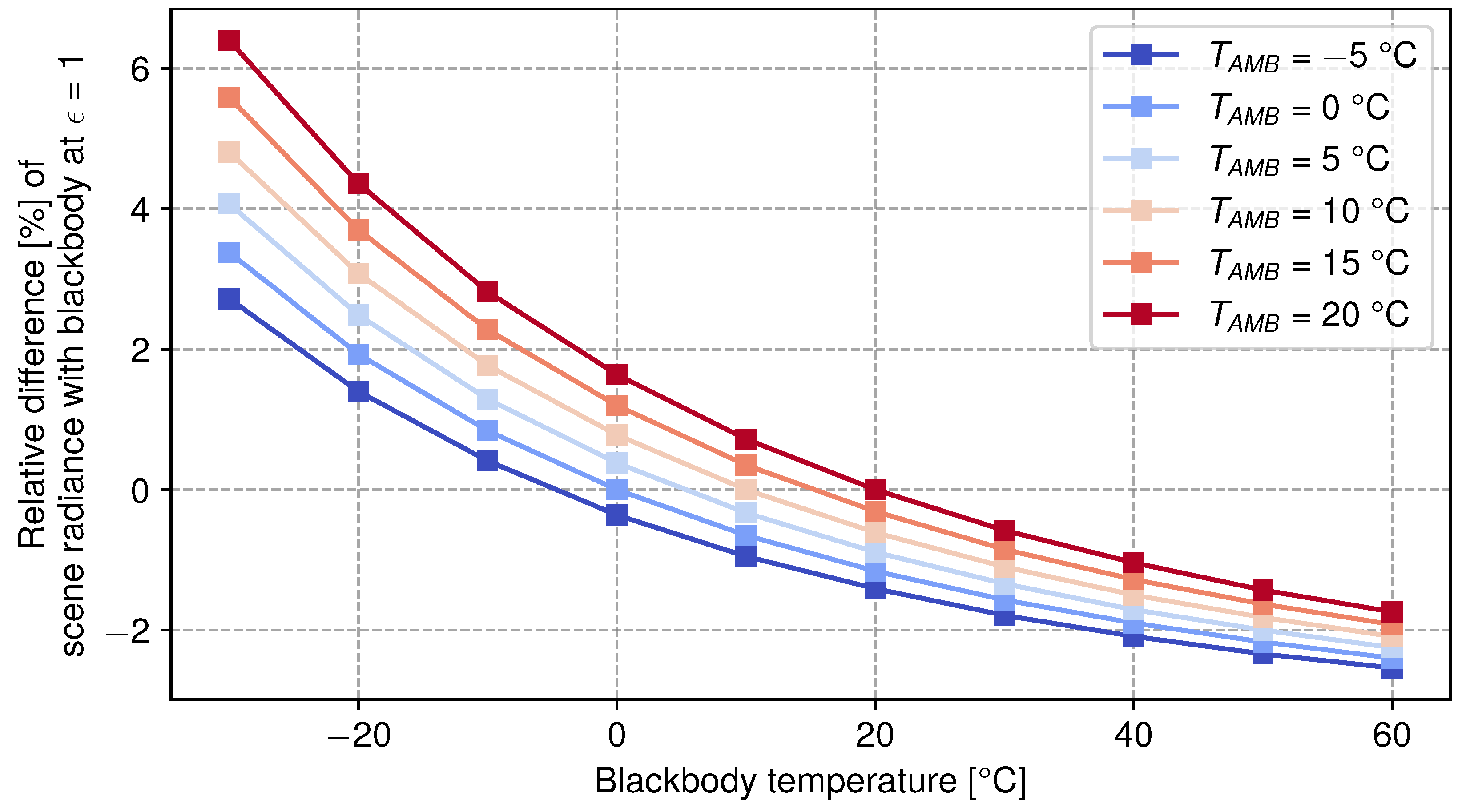

4.1. Bias in Scene Radiance Estimation

4.2. Remaining Fixed Pattern Noise in Calibrated Images

4.3. Non-Linearity Correction in Pixel Response

4.4. Correlation between Scene Radiance and Camera Temperature

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Analog-to-Digital Converter |

| ADU | Analog-to-Digital Units |

| BD | Bit-depth |

| CMOS | Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor |

| DSNU | Dark Signal Non-Uniformity |

| FFC | Flat-Field Correction |

| FOV | Field-of-View |

| FPA | Focal Plane Array |

| FPGA | Field-Programmable Gate Array |

| FPN | Fixed Pattern Noise |

| IR | Infrared |

| LWIR | Long-Wave Infrared |

| NETD | Noise Equivalent Temperature Difference |

| NERD | Noise Equivalent Radiance Difference |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| NUC | Non-uniformity Correction |

| PRNU | Pixel Response Non-Uniformity |

| PWV | Precipitable Water Vapor |

| RMSE | Root-Mean Square Error |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| UIRTC | Uncooled Infrared Thermal Camera |

References

- Magnier, E.A.; Schlafly, E.F.; Finkbeiner, D.P.; Tonry, J.L.; Goldman, B.; Röser, S.; Schilbach, E.; Casertano, S.; Chambers, K.C.; Flewelling, H.A.; Huber, M.E.; Price, P.A.; Sweeney, W.E.; Waters, C.Z.; Denneau, L.; Draper, P.W.; Hodapp, K.W.; Jedicke, R.; Kaiser, N.; Kudritzki, R.P.; Metcalfe, N.; Stubbs, C.W.; Wainscoat, R.J. Pan-STARRS Photometric and Astrometric Calibration. [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/1612.05242]. 2020, 251, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykoff, E.S.; Tucker, D.L.; Burke, D.L.; Allam, S.S.; Bechtol, K.; Bernstein, G.M.; Brout, D.; Gruendl, R.A.; Lasker, J.; Smith, J.A.; Wester, W.C.; Yanny, B.; Abbott, T.M.C.; Aguena, M.; Alves, O.; Andrade-Oliveira, F.; Annis, J.; Bacon, D.; Bertin, E.; Brooks, D.; Carnero Rosell, A.; Carretero, J.; Castander, F.J.; Choi, A.; da Costa, L.N.; Pereira, M.E.S.; Davis, T.M.; De Vicente, J.; Diehl, H.T.; Doel, P.; Drlica-Wagner, A.; Everett, S.; Ferrero, I.; Frieman, J.; García-Bellido, J.; Giannini, G.; Gruen, D.; Gutierrez, G.; Hinton, S.R.; Hollowood, D.L.; James, D.J.; Kuehn, K.; Lahav, O.; Marshall, J.L.; Mena-Fernández, J.; Menanteau, F.; Myles, J.; Nord, B.D.; Ogando, R.L.C.; Palmese, A.; Pieres, A.; Plazas Malagón, A.A.; Raveri, M.; Rodgríguez-Monroy, M.; Sanchez, E.; Santiago, B.; Schubnell, M.; Sevilla-Noarbe, I.; Smith, M.; Soares-Santos, M.; Suchyta, E.; Swanson, M.E.C.; Varga, T.N.; Vincenzi, M.; Walker, A.R.; Weaverdyck, N.; Wiseman, P. The Dark Energy Survey Six-Year Calibration Star Catalog. arXiv e-prints 2023. p. arXiv:2305.01695, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/2305.01695]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivezić. ; others. LSST: From Science Drivers to Reference Design and Anticipated Data Products. 2019, arXiv:astro-ph/0805.2366]873, 111. [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, C.W.; High, F.W.; George, M.R.; DeRose, K.L.; Blondin, S.; Tonry, J.L.; Chambers, K.C.; Granett, B.R.; Burke, D.L.; Smith, R.C. Toward More Precise Survey Photometry for PanSTARRS and LSST: Measuring Directly the Optical Transmission Spectrum of the Atmosphere. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 2007, 119, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, D.E.S. The LSST Dark Energy Science Collaboration (DESC) Science Requirements Document. 2018, arXiv:1809.01669. [Google Scholar]

- Betoule, M.; Antier, S.; Bertin, E.; Blanc, P.É.; Bongard, S.; Cohen Tanugi, J.; Dagoret-Campagne, S.; Feinstein, F.; Hardin, D.; Juramy, C.; Le Guillou, L.; Le Van Suu, A.; Moniez, M.; Neveu, J.; Nuss, É.; Plez, B.; Regnault, N.; Sepulveda, E.; Sommer, K.; Souverin, T.; Wang, X.F. StarDICE. I. Sensor calibration bench and absolute photometric calibration of a Sony IMX411 sensor. [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/2211.04913]. 2023, 670, A119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlin, R.C.; Hubeny, I.; Rauch, T. New Grids of Pure-hydrogen White Dwarf NLTE Model Atmospheres and the HST/STIS Flux Calibration. The Astronomical Journal 2020, 160, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larason, T.; Houston, J. Spectroradiometric Detector Measurements: Ultraviolet, Visible, and Near Infrared Detectors for Spectral Power, 2008.

- LSST Science Collaboration. LSST Science Book, Version 2.0. arXiv e-prints p. arXiv:0912.0201, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/0912.0201]. 2009, arXiv:0912.0201.

- Hazenberg, F. Calibration photométrique des supernovae de type Ia pour la caractérisation de l’énergie noire avec l’expérience StarDICE. Theses, Sorbonne Université, 2019.

- Burke, D.L.; Saha, A.; Claver, J.; Axelrod, T.; Claver, C.; DePoy, D.; Ivezić, Ž.; Jones, L.; Smith, R.C.; Stubbs, C.W. ALL-WEATHER CALIBRATION OF WIDE-FIELD OPTICAL AND NIR SURVEYS. The Astronomical Journal 2013, 147, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, D.L.; Rykoff, E.S.; Allam, S.; Annis, J.; Bechtol, K.; Bernstein, G.M.; Drlica-Wagner, A.; Finley, D.A.; Gruendl, R.A.; James, D.J.; Kent, S.; Kessler, R.; Kuhlmann, S.; Lasker, J.; Li, T.S.; Scolnic, D.; Smith, J.; Tucker, D.L.; Wester, W.; Yanny, B.; Abbott, T.M.C.; Abdalla, F.B.; Benoit-Levy, A.; Bertin, E.; Rosell, A.C.; Kind, M.C.; Carretero, J.; Cunha, C.E.; D’Andrea, C.B.; da Costa, L.N.; Desai, S.; Diehl, H.T.; Doel, P.; Estrada, J.; Garcia-Bellido, J.; Gruen, D.; Gutierrez, G.; Honscheid, K.; Kuehn, K.; Kuropatkin, N.; Maia, M.A.G.; March, M.; Marshall, J.L.; Melchior, P.; Menanteau, F.; Miquel, R.; Plazas, A.A.; Sako, M.; Sanchez, E.; Scarpine, V.; Schindler, R.; Sevilla-Noarbe, I.; Smith, M.; Smith, R.C.; Soares-Santos, M.; Sobreira, F.; Suchyta, E.; Tarle, G.; and, A.R.W. Forward Global Photometric Calibration of the Dark Energy Survey. The Astronomical Journal 2017, 155, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szejwach, G. Determination of Semi-Transparent Cirrus Cloud Temperature from Infrared Radiances: Application to METEOSAT. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 1982, 21, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.A.; Nugent, P.W. Physics principles in radiometric infrared imaging of clouds in the atmosphere. European Journal of Physics 2013, 34, S111–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liandrat, O.; Cros, S.; Braun, A.; Saint-Antonin, L.; Decroix, J.; Schmutz, N. Cloud cover forecast from a ground-based all sky infrared thermal camera. Remote Sensing of Clouds and the Atmosphere XXII. SPIE, 2017, Vol. 10424, pp. 19–31.

- Lopez, T.; Antoine, R.; Baratoux, D.; Rabinowicz, M. Contribution of thermal infrared images on the understanding of the subsurface/atmosphere exchanges on Earth. EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, 2017, p. 11811.

- Klebe, D.I.; Blatherwick, R.D.; Morris, V.R. Ground-based all-sky mid-infrared and visible imagery for purposes of characterizing cloud properties. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2014, 7, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolenko, I.; Maslov, I. Infrared (thermal) camera for monitoring the state of the atmosphere above the sea horizon of the Simeiz Observatory INASAN. INASAN Science Reports 2021, 6, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, J.A.; others. Radiometric cloud imaging with an uncooled microbolometer thermal infrared camera. Optics Express 2005, 13, 5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocard, E.; others. Detection of Cirrus Clouds Using Infrared Radiometry. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2011, 49, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebag, J.; Andrew, J.; Klebe, D.; Blatherwick, R. LSST all-sky IR camera cloud monitoring test results. Proceedings of SPIE - The International Society for Optical Engineering 2010, 7733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.M.; Rogers, H.; Schindler, R.H. A radiometric all-sky infrared camera (RASICAM) for DES/CTIO. Ground-based and Airborne Instrumentation for Astronomy III. SPIE, 2010, Vol. 7735, pp. 1307–1318.

- Hack, E.D.; Pauliquevis, T.; Barbosa, H.M.J.; Yamasoe, M.A.; Klebe, D.; Correia, A.L. Precipitable water vapor retrievals using a ground-based infrared sky camera in subtropical South America. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2023, 16, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poissenot-Arrigoni, C.; Marcon, B.; Rossi, F.; Fromentin, G. Fast and easy radiometric calibration method integration time insensitive for infrared thermography. Infrared Physics & Technology 2023, 133, 104741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, P.W.; others. Correcting for focal-plane-array temperature dependence in microbolometer infrared cameras lacking thermal stabilization. Optical Engineering 2013, 52, 061304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Gomes, K.; Hernández-López, D.; Ortega, J.F.; Ballesteros, R.; Poblete, T.; Moreno, M.A. Uncooled Thermal Camera Calibration and Optimization of the Photogrammetry Process for UAV Applications in Agriculture. Sensors 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Chávez, O.; Cárdenas-Garcia, D.; Karaman, S.; Lizárraga, M.; Salas, J. Radiometric Calibration of Digital Counts of Infrared Thermal Cameras. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2019, 68, 4387–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benirschke, D.; Howard, S. Characterization of a low-cost, commercially available, vanadium oxide microbolometer array for spectroscopic imaging. Optical Engineering 2017, 56, 040502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdelidis, N.; Moropoulou, A. Emissivity considerations in building thermography. Energy and Buildings 2003, 35, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, L. Nguyen.; Flir Systems. Flat field correction for infrared cameras, U.S. Patent US8373757B1 2009.

- Joseph, L. Kostrzewa.; Vu L. Nguyen.; Theodore R. Hoelter.; Flir Systems. Flat field correction for infrared cameras, U.S. Patent US20130147966A1 2013.

- Mudau, A.E.; Willers, C.J.; Griffith, D.; le Roux, F.P. Non-uniformity correction and bad pixel replacement on LWIR and MWIR images. 2011 Saudi International Electronics, Communications and Photonics Conference (SIECPC). IEEE, 2011, pp. 1–5.

- Budzier, H.; Gerlach, G. Calibration of uncooled thermal infrared cameras. Journal of Sensors and Sensor Systems 2015, 4, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Whitenton, E. Calibration and measurement procedures for a high magnification thermal camera. Report no. NISTIR8098 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, 2015) 2015.

- Tempelhahn, A.; Budzier, H.; Krause, V.; Gerlach, G. Shutter-less calibration of uncooled infrared cameras. Journal of Sensors and Sensor Systems 2016, 5, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempelhahn, A.; Budzier, H.; Krause, V.; Gerlach, G. P3-Modeling Signal-Determining Radiation Components of Microbolometer-Based Infrared Measurement Systems. Proceedings IRS2 2013, 2013, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bhan, R.; Saxena, R.; Jalwania, C.; Lomash, S. Uncooled Infrared Microbolometer Arrays and their Characterisation Techniques. Defence Science Journal 2009, 59, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagnoli, E.; Giunti, C.; Mariani, P.; Olivieri, M.; Porta, A.; Sozzi, B.; Zatti, S. Thermal imager non-uniformity sources modeling. Infrared Imaging Systems: Design, Analysis, Modeling, and Testing XXII. SPIE, 2011, Vol. 8014, pp. 88–99.

- Efron, B. Better Bootstrap Confidence Intervals. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1987, 82, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembinski, H.; et al., P.O. scikit-hep/iminuit. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.W.; Abel, I.R. Narcissus: reflections on retroreflections in thermal imaging systems. Applied Optics 1982, 21, 3393–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emde, C.; Buras-Schnell, R.; Kylling, A.; Mayer, B.; Gasteiger, J.; Hamann, U.; Kylling, J.; Richter, B.; Pause, C.; Dowling, T.; Bugliaro, L. The libRadtran software package for radiative transfer calculations (version 2.0.1). Geoscientific Model Development 2016, 9, 1647–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.P.; Clough, S.A.; Kneizys, F.X.; Chetwynd, J.H.; Shettle, E.P. AFGL (Air Force Geophysical Laboratory) atmospheric constituent profiles (0. 120km). Environmental research papers.

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; Schepers, D.; Simmons, A.; Soci, C.; Dee, D.; Thépaut, J.N. ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), 2023. Accessed on DD-MMM-YYYY. [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, V.; Riley, S.; Minschwaner, K. Atmospheric precipitable water vapor and its correlation with clear-sky infrared temperature observations. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2022, 15, 1563–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, J.; Nishino, H.; Kusaka, A. Precipitable water vapour measurement using GNSS data in the Atacama Desert for millimetre and submillimetre astronomical observations. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2024, 528, 4582–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeij, M.F.; Theuwissen, A.J.P.; Makinwa, K.A.A.; Huijsing, J.H. A CMOS Imager With Column-Level ADC Using Dynamic Column Fixed-Pattern Noise Reduction. IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits 2006, 41, 3007–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kang, M.G. Infrared Image Deconvolution Considering Fixed Pattern Noise. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, J.; Lai, R.; Xiong, A.; Liu, Z.; Gu, L. Fixed pattern noise reduction for infrared images based on cascade residual attention CNN. Neurocomputing 2020, 377, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.; Caldwell, L. Nonuniformity correction and correctability of infrared focal plane arrays. Infrared physics & technology 1995, 36, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, S.; Lai, R.; Wang, D.; Cheng, Y. Solution for the nonuniformity correction of infrared focal plane arrays. Appl. Opt. 2005, 44, 2928–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, P.; White, D. Propagation of Uncertainty Due to Non-linearity in Radiation Thermometers. International Journal of Thermophysics 2007, 28, 2098–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, B.; Tian, P. Pixel-wise radiometric calibration approach for infrared focal plane arrays using multivariate polynomial correction. Infrared Physics & Technology 2022, 123, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, O.; Bosser, P.; Bourcy, T.; David, L.; Goutail, F.; Hoareau, C.; Keckhut, P.; Legain, D.; Pazmino, A.; Pelon, J.; Pipis, K.; Poujol, G.; Sarkissian, A.; Thom, C.; Tournois, G.; Tzanos, D. Accuracy assessment of water vapour measurements from in situ and remote sensing techniques during the DEMEVAP 2011 campaign at OHP. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2013, 6, 2777–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaykin, S.M.; Godin-Beekmann, S.; Keckhut, P.; Hauchecorne, A.; Jumelet, J.; Vernier, J.P.; Bourassa, A.; Degenstein, D.A.; Rieger, L.A.; Bingen, C.; Vanhellemont, F.; Robert, C.; DeLand, M.; Bhartia, P.K. Variability and evolution of the midlatitude stratospheric aerosol budget from 22 years of ground-based lidar and satellite observations. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2017, 17, 1829–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holben, B.; Eck, T.; Slutsker, I.; Tanré, D.; Buis, J.; Setzer, A.; Vermote, E.; Reagan, J.; Kaufman, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Lavenu, F.; Jankowiak, I.; Smirnov, A. AERONET—A Federated Instrument Network and Data Archive for Aerosol Characterization. Remote Sensing of Environment 1998, 66, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozovsky, I.; Ansmann, A.; Althausen, D.; Heese, B.; Engelmann, R.; Hofer, J.; Baars, H.; Schechner, Y.; Lyapustin, A.; Chudnovsky, A. Impact of aerosol layering, complex aerosol mixing, and cloud coverage on high-resolution MAIAC aerosol optical depth measurements: Fusion of lidar, AERONET, satellite, and ground-based measurements. Atmospheric Environment 2021, 247, 118163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, V.; Riley, S.; Minschwaner, K. Atmospheric precipitable water vapor and its correlation with clear-sky infrared temperature observations. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2022, 15, 1563–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier Valdés, E. A. .; Morris, B. M..; Demory, B.-O.. Monitoring precipitable water vapour in near real-time to correct near-infrared observations using satellite remote sensing. A&A 2021, 649, A132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, J.; Nishino, H.; Kusaka, A. Precipitable Water Vapor Measurement using GNSS Data in the Atacama Desert for Millimeter and Submillimeter Astronomical Observations, 2023, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/2308.12632].

- Thurairajah, B.; Shaw, J. Cloud statistics measured with the infrared cloud imager (ICI). IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2005, 43, 2000–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astropy Collaboration, T. Astropy: A community Python package for astronomy. AJ 2018, 156, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.K.; Pitrou, A.; Seibert, S. Numba: A llvm-based python jit compiler. Proceedings of the Second Workshop on the LLVM Compiler Infrastructure in HPC, 2015, pp. 1–6.

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; Kern, R.; Picus, M.; Hoyer, S.; van Kerkwijk, M.H.; Brett, M.; Haldane, A.; del Rio, J.F.; Wiebe, M.; Peterson, P.; Gerard-Marchant, P.; Sheppard, K.; Reddy, T.; Weckesser, W.; Abbasi, H.; Gohlke, C.; Oliphant, T.E. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Brett, M.; Wilson, J.; Millman, K.J.; Mayorov, N.; Nelson, A.R.J.; Jones, E.; Kern, R.; Larson, E.; Carey, C.J.; Polat, İ.; Feng, Y.; Moore, E.W.; VanderPlas, J.; Laxalde, D.; Perktold, J.; Cimrman, R.; Henriksen, I.; Quintero, E.A.; Harris, C.R.; Archibald, A.M.; Ribeiro, A.H.; Pedregosa, F.; van Mulbregt, P. SciPy 1.0 Contributors. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.D. CSE2007, 9, 90. [CrossRef]

| 1 | The f#-number is defined as the ratio of the focal length to the diameter of the aperture. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Code for the FLIR Tau2 camera with TeAx ThermalGrabber https://github.com/Kelian98/tau2_thermalcapture

|

| 6 | Code for the IR2101 blackbody https://github.com/Kelian98/ir2101_blackbody

|

| 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).