Submitted:

09 July 2024

Posted:

10 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

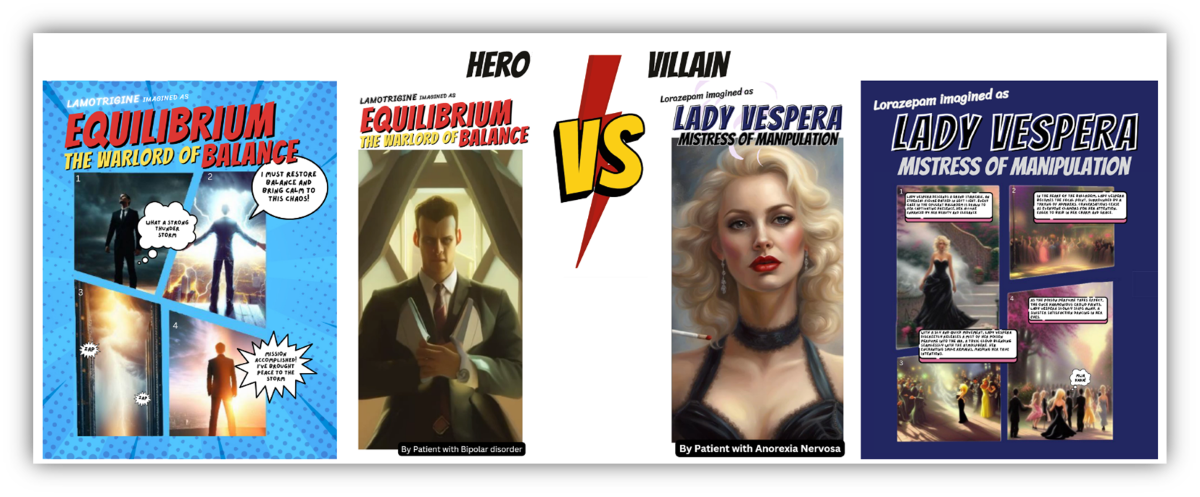

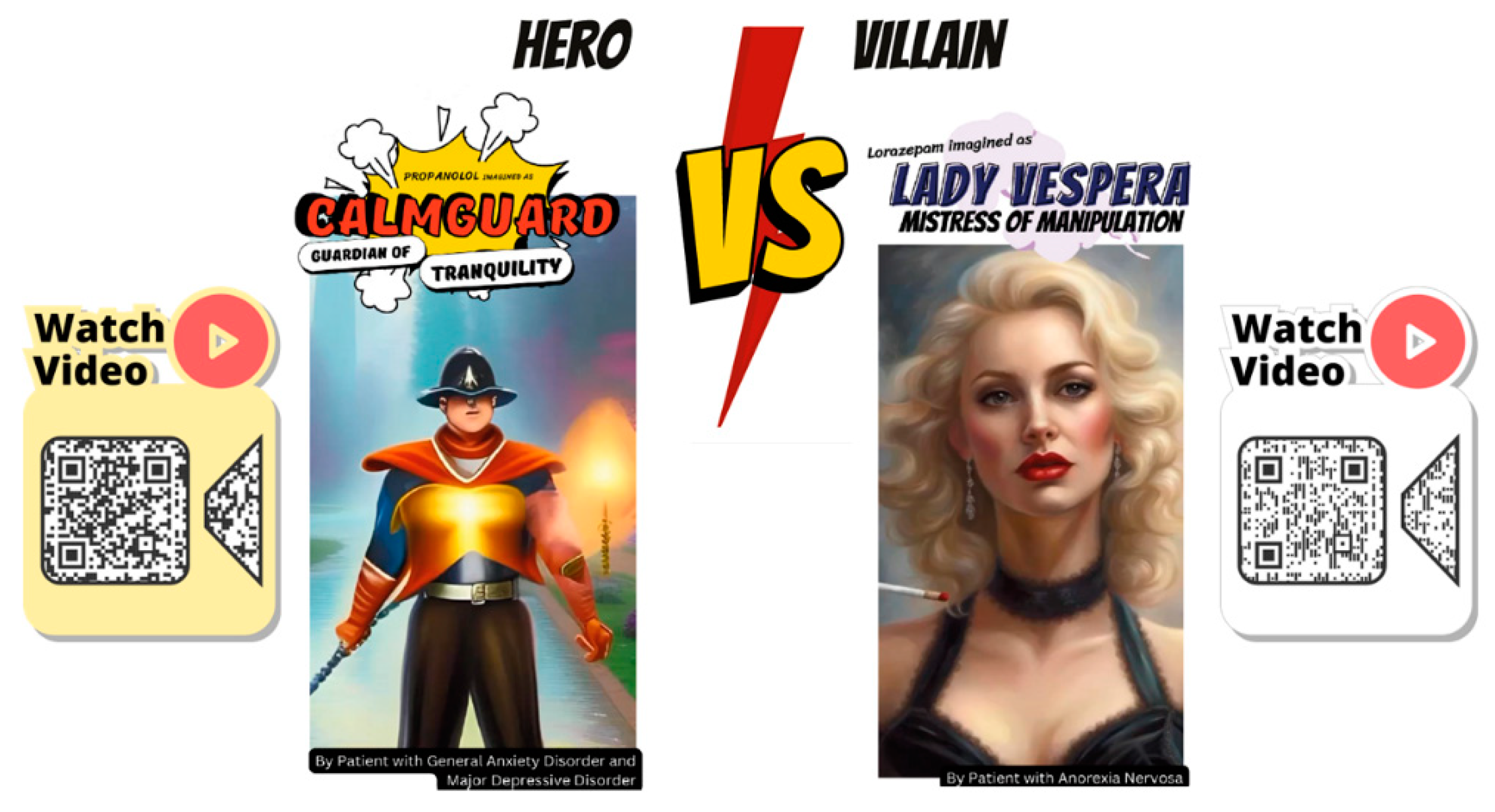

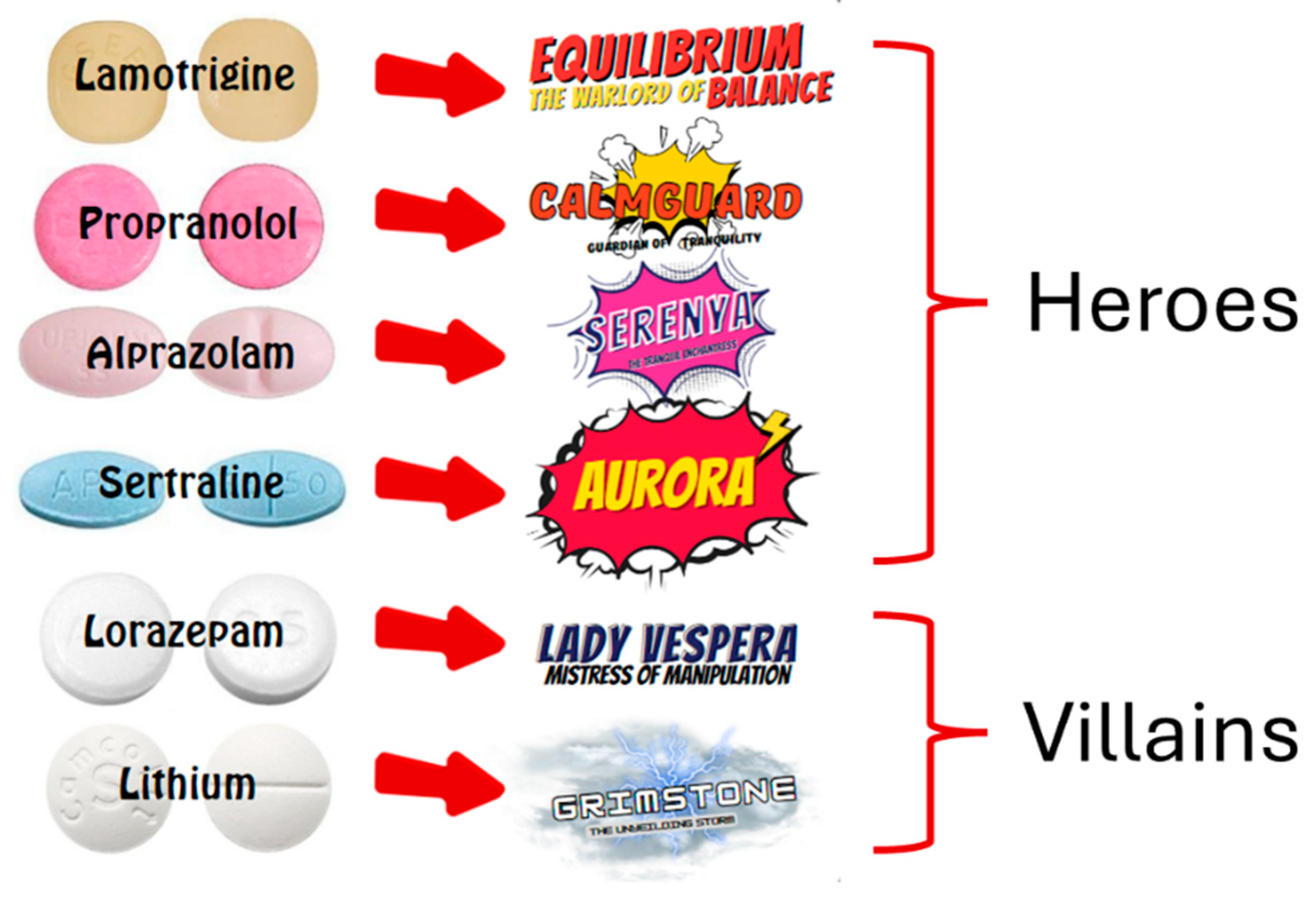

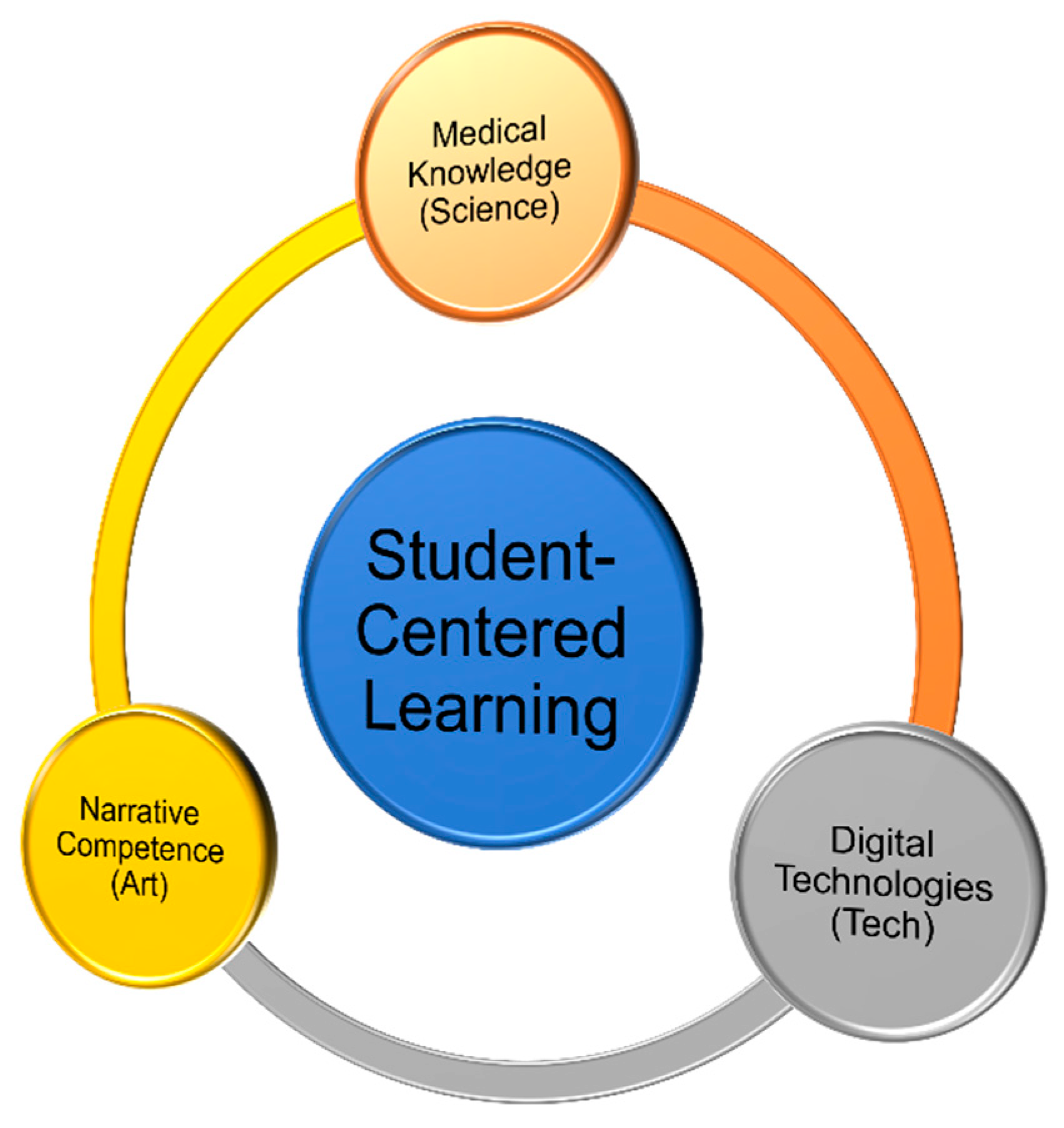

2.1. Design and Development of the Metaverse Art Gallery of Image Chronicles (MAGIC)

2.2. Alpha Testing of MAGIC

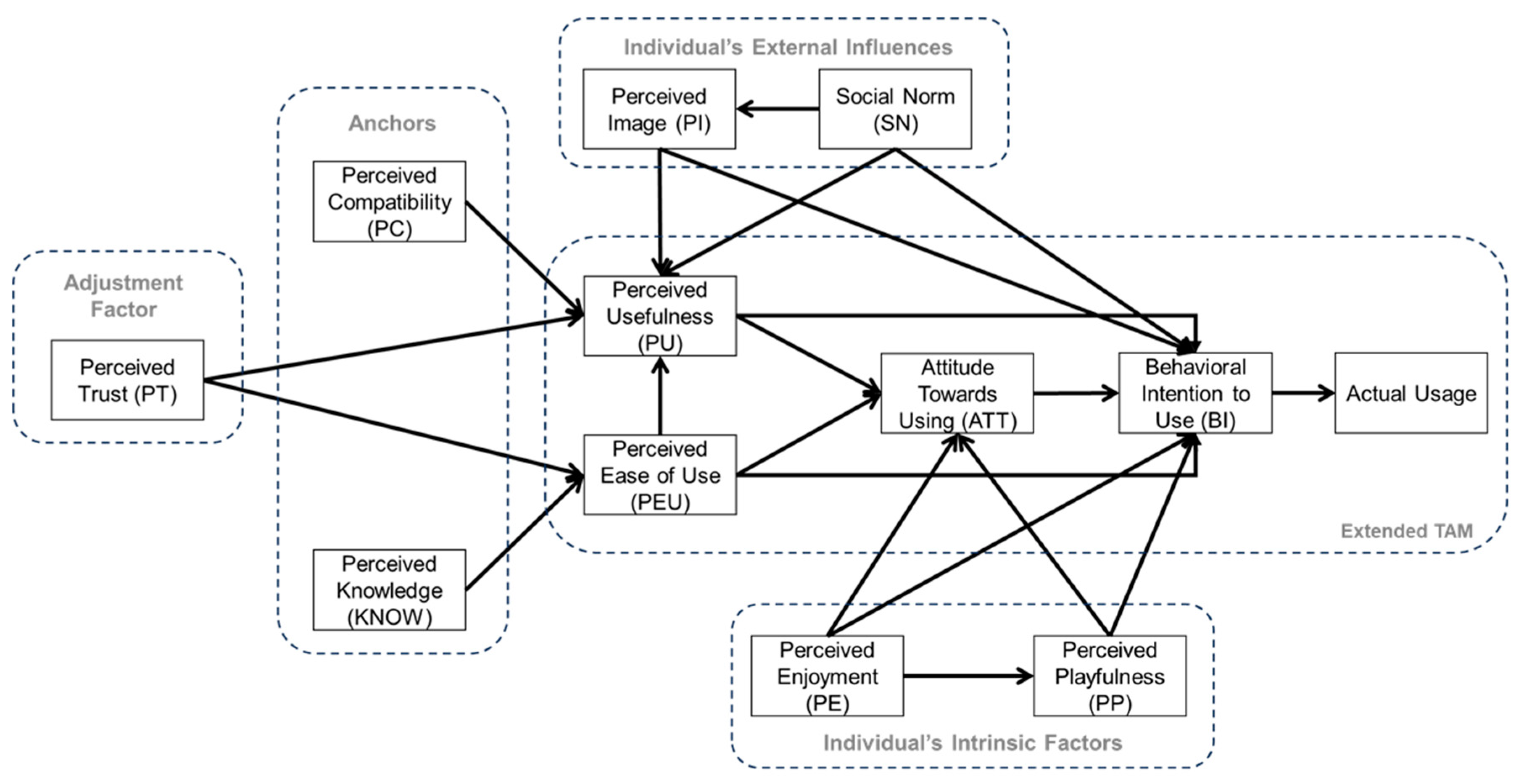

2.2.1. Research Model

2.2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Three MAGIC Realms

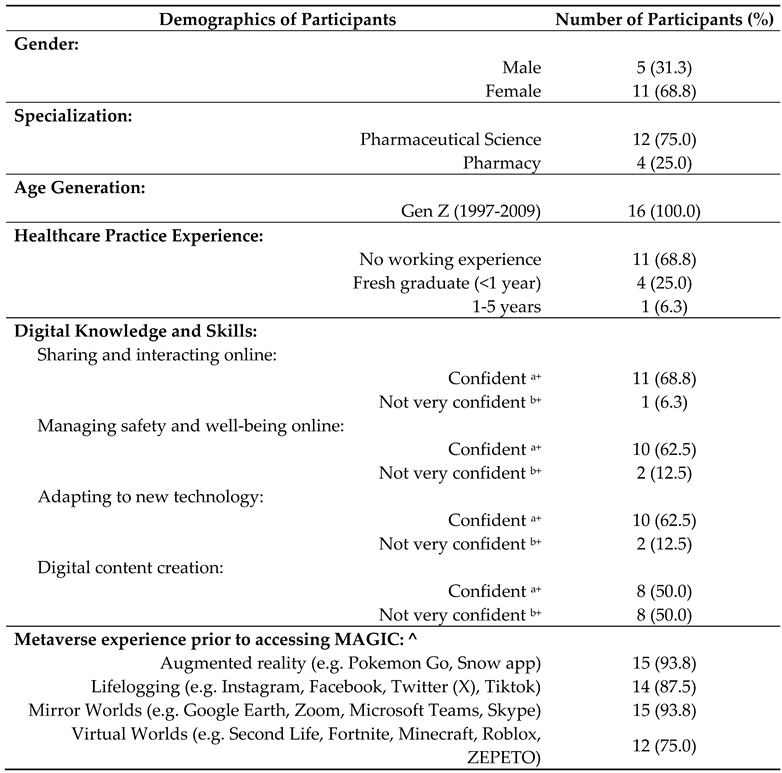

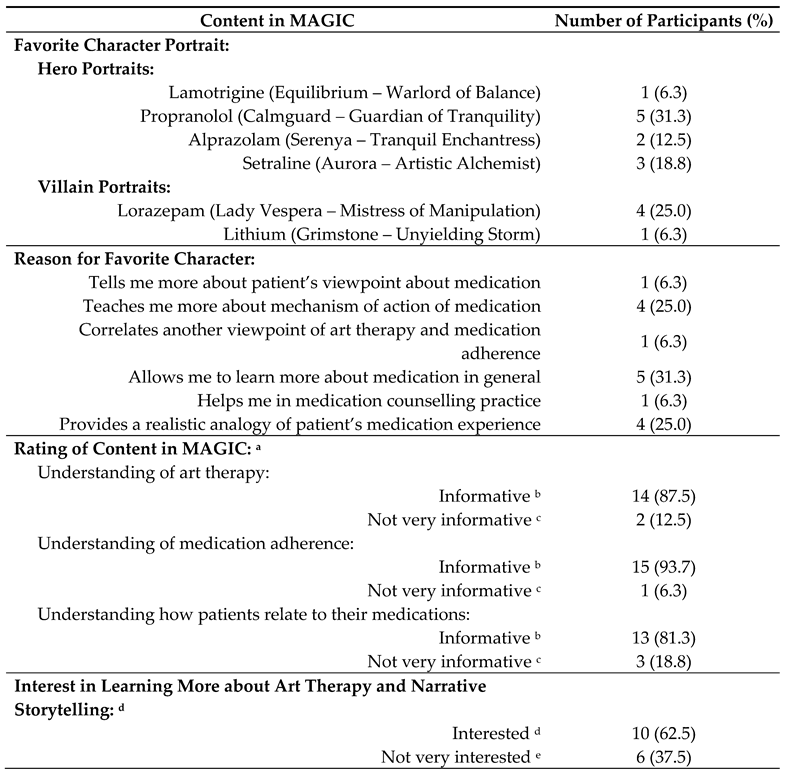

3.2. Learners’ Demographics and Perceptions of MAGIC

3.3. TAM Scale Reliability

3.4. Learners’ Perceptions of MAGIC

3.5. Correlation of TAM Measures with Participants’ Behavioral Intention to Use MAGIC

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- British Association of Art Therapists. Art therapy. British Association of Art Therapists, 2023. Available online: https://baat.org/art-therapy/ (accessed on 19 Apr 2023).

- American Art Therapy Association. About art therapy. American Art Therapy Association, 2022. Available online: https://arttherapy.org/about-art-therapy/ (accessed on 19 Apr 2023).

- Hu, J.; Zhang, J.; Hu, L.; Yu, H.; Xu, J. Art therapy: A complementary treatment for mental disorders. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 686005. [CrossRef]

- American Art Therapy Association. Ethical principles for art therapists; American Art Therapy Association, 2013, pp. 1-16.

- Malchiodi, C.A. Who owns the art? An ethical question for art therapists and clinicians. In Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) Facility Report, US Department of Education; Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) Facility, US Department of Education: Salt Lake City, UT, 1995, pp. 1-7.

- Miller, G.; McDonald, A. Online art therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Art Therapy 2020, 25, 159-160. [CrossRef]

- Hacmun, I.; Regev, D.; Salomon, R. The principles of art therapy in virtual reality. Front Psychol 2018, 9, 2082. [CrossRef]

- Hogenmiller, M. How art and technology can work together to facilitate healing. Arts Management & Technology Laboratory, Carnegie Mellon University, 2021. Available online: https://amt-lab.org/blog/2021/11/art-therapy-meets-the-metaverse-how-can-art-and-technology-work-together-to-facilitate-healing (accessed on 19 Apr 2023).

- Korp, A. What the brain shows: The benefits of virtual reality in creative arts therapies. In Drexel News; Drexel University: Philadelphia, PA, 2021.

- McKinsey & Company. What is generative AI?, 2023. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-generative-ai (accessed on 27 Apr 2023).

- Edwards, R.M.; I’Anson, J. An innovative method of data analysis: Using art as a lens through which to view pharmacy undergraduate students’ learning and assessment practices. Res Social Adm Pharm 2022, 18, 2213-2221. [CrossRef]

- Kear, J. Pierre Bonnard Coffee 1915, 2016. Available online: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/bonnard-coffee-n05414 (accessed on 27 Apr 2023).

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The bioecological model of human development. In Handbook of Child Psychology. Volume I. Theoretical Models of Human Development; John Wiley & Sons, 2007; Volume I, pp. 793-828.

- Charon, R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA 2001, 286, 1897-1902. [CrossRef]

- Velazco, C. Mark Zuckerberg just laid out his vision for the metaverse. These are the five things you should know. The Washington Post, 2021. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/10/28/facebook-meta-metaverse-explained/ (accessed on 29 Jun 2024).

- Wiles, J. What is a metaverse? And should you be buying it? Gartner, 2022. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/articles/what-is-a-metaverse (accessed on 16 Jan 2023).

- Mesko, B. The promise of the metaverse in cardiovascular health. Eur Heart J 2022, 43, 2647-2649. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. What is a Metaverse? Gartner Inc., 2022. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/articles/what-is-a-metaverse (accessed on Sep 14 2022).

- Kustiawan, P. Metaverse and its benefits for education. Global Millennial Group, 2022. Available online: https://gmillennial.com/metaverse-and-its-benefits-for-education/ (accessed on Sep 14 2022).

- Kye, B.; Han, N.; Kim, E.; Park, Y.; Jo, S. Educational applications of metaverse: Possibilities and limitations. J Educ Eval Health Prof 2021, 18, 32. [CrossRef]

- Koo, H. Training in lung cancer surgery through the metaverse, including extended reality, in the smart operating room of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Korea. J Educ Eval Health Prof 2021, 18, 33. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Tan, S.; Yap, K. The Saltomachy War - A metaverse escape room on the War Against Salt. Stud Health Technol Inform 2024, 310, 1251-1255.

- Yap, K. Developing a digital health metacademy for continuing professional education. Stud Health Technol Inform 2024, 310, 1536-1537.

- Chamola, V.; Bansal, G.; Das, T.K.; Hassija, V.; Reddy, N.S.S.; Wang, J.; Zeadally, S.; Hussain, A.; Yu, F.R.; Guizani, M.; Niyato, D. Beyond reality: The pivotal role of generative AI in the metaverse. Cornell University, 2023. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2308.06272 (accessed on 2 Oct 2023).

- Shahriar, S. GAN computers generate arts? A survey on visual arts, music, and literary text generation using generative adversarial network. Displays 2022, 73, 102237.

- Cao, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Dai, Y.; Yu, P.S.; Sun, L. A comprehensive survey of AI-generated content (AIGC): A history of generative AI from GAN to ChatGPT. ArXiv 2023, abs/2303.04226.

- Lathan, C. Generative AI in the metaverse. Psychology Today, 2023. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/inventing-the-future/202306/generative-ai-in-the-metaverse (accessed on 4 Oct 2023).

- Ursachi, G.; Horodnic, I.A.; Zait, A. How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Economics and Finance 2015, 20, 679-686. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly 1989, 13, 319-340.

- Davis, F.D.; Granić, A. The Technology Acceptance Model - 30 Years of TAM; Springer Cham: Switzerland AG, 2024; pp. 1-117.

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decision Sci 2008, 39, 273-315. [CrossRef]

- Aburbeian, A.M.; Owda, A.Y.; Owda, M. A Technology Acceptance Model survey of the metaverse prospects. AI 2022, 3, 285-302. [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.P.; Orruno, E.; Asua, J.; Abdeljelil, A.B.; Emparanza, J. Using a modified technology acceptance model to evaluate healthcare professionals’ adoption of a new telemonitoring system. Telemed J E Health 2012, 18, 54-59. [CrossRef]

- Toraman, Y.; Gecit, B.B. User acceptance of metaverse: An analysis for e-commerce in the framework of Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Sosyoekonomi 2023, 31, 85-104. [CrossRef]

- Alsharhan, A.; Salloum, S.A.; Aburayya, A. Technology acceptance drivers for AR smart glasses in the middle east: A quantitative study. Int J Data Netw Sci 2022, 6, 193-208. [CrossRef]

- Suh, W.; Ahn, S. Utilizing the Metaverse for Learner-Centered Constructivist Education in the Post-Pandemic Era: An Analysis of Elementary School Students. J Intell 2022, 10.

- Mostafa, l. Measuring Technology Acceptance Model to use metaverse technology in Egypt. JSST 2022, 23, 118-142. [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr., J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson College Div: USA, 2009; pp. 785.

- N.A. Three-body problem. Wikipedia, 2024. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three-body_problem (accessed on 5 Apr 2024).

- Devine, S. Therapeutic impact of public art exhibits during COVID-19. Art Therapy 2022, 40, 50-54. [CrossRef]

- Vick, R.M. Ethics on exhibit. Art Therapy 2011, 28, 152-158.

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Li, N.; Al-Adwan, A.; Abbasi, G.A.; Albelbisi, N.A.; Habibi, A. “Extending the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to predict university students’ intentions to use metaverse-based learning platforms”. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr) 2023, 1-33.

- Kalinkara, Y.; Ozdemir, O. Anatomy in the metaverse: Exploring student technology acceptance through the UTAUT2 model. Anat Sci Educ 2024, 17, 319-336. [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Yang, F.; Gu, C.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. A study of factors influencing Chinese college students’ intention of using metaverse technology for basketball learning: Extending the technology acceptance model. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 1049972. [CrossRef]

- Ostherr, K. Digital Health Humanities. In Research Methods in Health Humanities; Klugman, C.M., Lamb, E.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019, pp. 182-198.

| TAM Measures | Number of Items/Statements | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Enjoyment (PE) | 2 | 0.639 |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 3 | 0.670 |

| Perceived Playfulness (PP) | 4 | 0.760 |

| Perceived Trust (PT) | 3 | 0.857 |

| Perceived Knowledge (KNOW) | 2 | 0.414 |

| Social Norm (SN) | 3 | 0.746 |

| Perceived Compatibility (PC) | 3 | 0.787 |

| Perceived Image (PI) | 3 | 0.936 |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) | 4 | 0.633 |

| Attitude Towards Use (ATT) | 3 | 0.910 |

| Behavioral Intention (BI) | 3 | 0.735 |

| Overall Total | 33 | 0.943 |

| TAM Measures | TAM Parameters/Statements | Scores for TAM Statements a (Average ± SD) |

Average Score for TAM Measures a (Average ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Enjoyment (PE) | • I find the eduverse enjoyable. | 6.31 ± 0.70 | 6.13 ± 0.67 |

| • The metaverse will enhance learning experiences of learners & make it more fun. | 5.94 ± 0.85 | ||

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | • Learning through the eduverse has the potential to be more effective than traditional learning methods. | 5.94 ± 0.93 | 5.85 ± 0.72 |

| • I find the eduverse useful for education. | 6.13 ± 0.62 | ||

| • Using the eduverse can improve my learning performance. | 5.50 ± 1.16 | ||

| Perceived Playfulness (PP) | • Using the eduverse is an interactive & engaging experience. | 6.25 ± 0.78 | 5.80 ± 071 |

| • I do not realize that time has elapsed when in the eduverse. | 5.06 ± 1.18 | ||

| • I was actively exploring the eduverse. | 5.75 ± 1.07 | ||

| • The design of eduverse (environment, elements, characters) is appealing. | 6.13 ± 0.62 | ||

| Perceived Trust (PT) | • I trust that the metaverse platform that hosts the eduverse is secure. | 5.69 ± 0.79 | 5.77 ± 0.88 |

| • I trust that the metaverse platform that hosts the eduverse is reliable. | 5.81 ± 1.05 | ||

| • I believe that the metaverse platform that hosts the eduverse is trustworthy. | 5.81 ± 1.11 | ||

| Perceived Knowledge (KNOW) | • I have good knowledge about the metaverse. | 5.56 ± 0.81 | 5.66 ± 0.72 |

| • I know the difference between virtual reality and the metaverse. | 5.75 ± 1.00 | ||

| Social Norm (SN) | • Most of my classmates will welcome the use of metaverse for education & learning. | 5.69 ± 0.79 | 5.46 ± 0.85 |

| • Most of my lecturers will welcome the fact that I use metaverse for teaching/learning. | 5.56 ± 1.03 | ||

| • I want to try the metaverse due to its technological hype. | 5.13 ± 1.26 | ||

| Perceived Compatibility (PC) | • Using the eduverse fits well with my learning style. | 5.44 ± 1.03 | 5.44 ± 0.96 |

| • Using the eduverse fits well with my lifestyle. | 5.13 ± 1.41 | ||

| • Using the metaverse for education may imply major changes to the way in which education is carried out. | 5.75 ± 0.93 | ||

| Perceived Image (PI) | • People who have been in the metaverse are more trendy. | 5.13 ± 1.20 | 5.19 ± 1.15 |

| • I feel more tech-savvy compared to my friends after using the eduverse. | 5.31 ± 1.14 | ||

| • I am glad I am among the first in my organization to use the metaverse. | 5.13 ± 1.31 | ||

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) | • Learning how to navigate the eduverse is easy for me. | 5.81 ± 0.91 | 5.11 ± 0.42 |

| • I find it easy to do what I want to do in the eduverse. | 5.44 ± 0.89 | ||

| • Using the eduverse requires a lot of mental effort to play. b | 3.25 ± 1.73 | ||

| • The controls are intuitive & I have no trouble using the controls to perform tasks in the eduverse. | 5.94 ± 0.85 | ||

| Attitude Towards Use (ATT) c | • Using the eduverse for learning is a good / bad idea. | 5.44 ± 0.81 | 5.67 ± 0.82 |

| • I am positive / negative toward using the eduverse for learning. | 5.75 ± 0.86 | ||

| • I am satisfied / unsatisfied with my learning experience in the eduverse. | 5.81 ± 0.98 | ||

| Behavioral Intention (BI) | • I would like to explore the metaverse for my future learning. | 5.81 ± 0.91 | 5.81 ± 0.79 |

| • I would use the metaverse for learning/education on a more regular basis if I had access to it. | 5.69 ± 1.14 | ||

| • I would recommend the eduverse for learning to others for their education. | 5.94 ± 0.85 |

| TAM Measures a | Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient (rs) b | P-value | 95% Confidence Interval | Exploratory Factor Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 Loadings | Factor 2 Loadings | Extraction Communalities c | ||||

| Perceived Enjoyment (PE) | 0.608 | 0.012* | 0.114, 0.861 | 0.583 | 0.535 | 0.627 |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 0.789 | <0.001* | 0.419, 0.934 | 0.769 | 0.398 | 0.750 |

| Perceived Playfulness (PP) | 0.925 | <0.001* | 0.749, 0.979 | 0.890 | 0.291 | 0.877 |

| Perceived Trust (PT) | 0.647 | 0.007* | 0.171, 0.878 | 0.849 | –0.008 | 0.721 |

| Social Norm (SN) | 0.862 | <0.001* | 0.582, 0.959 | 0.961 | 0.106 | 0.935 |

| Perceived Compatibility (PC) | 0.890 | <0.001* | 0.652, 0.968 | 0.975 | –0.007 | 0.951 |

| Perceived Image (PI) | 0.680 | 0.004* | 0.222, 0.892 | 0.941 | –0.142 | 0.906 |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) | 0.249 | 0.352 | –0.289, 0.668 | –0.112 | 0.917 | 0.853 |

| Attitude Towards Use (ATT) | 0.451 | 0.079 | –0.084, 0.784 | 0.094 | 0.885 | 0.791 |

| Behavioral Intention (BI) | -- | -- | -- | 0.892 | 0.270 | 0.869 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).