1. Introduction

Worldwide, the utilization of complementary medicines varies significantly, with usage rates ranging from 24% to 71.3% [

1]. Complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) encompass various products, such as vitamins, minerals, herbal preparations, and nutritional supplements. A recent cross-sectional study conducted in Australia reported that 50.3% of the study participants (n=2019) used CAM products with majority of the population using vitamin/mineral supplements (47.8%) [

2]. Females are more likely to use CAMs than males. In Australia, patients with a chronic disease diagnosis are also more likely to use CAMs compared to the general population [

2].

Community pharmacies play a substantial role in offering a wide array of CAM to consumers [

3]. Community pharmacists are strategically positioned within the community which allows them to be involved in a broad range of health promotion campaigns and services in addition to promoting safe and effective CAMs use [

3,

4]. While there is evidence for an increased role for pharmacists in the realm of CAMs utilization, the specific levels, and types of pharmaceutical care that community pharmacists should offer concerning these products remain unclear [

5]. This ambiguity is particularly concerning given that many CAMs lack rigorous research to support their use and may cause harm if not used appropriately [

6].

The utilization of certain CAM in disease treatment and prevention has raised concerns. The widespread use of CAM often stems from the perception that these products are inherently safe [

5]. Nonetheless, this belief lacks robust scientific evidence which shows significant prevalence of adverse reactions and drug interactions associated with the use of CAMs [

5]. Literature consistently underscored the potential for serious toxicities and adverse reactions linked to the use of CAMs products [

7]. However, research on CAM-related adverse events in Australia is limited.

A study by the National Prescribing Service found that consumers often perceive complementary medicines as safer alternatives to conventional medications, yet they may not be fully informed about the potential risks associated with them, including side effects, toxicity, the possibility of allergic reactions, and interactions with conventional medication [

8].

Another study conducted in the United States of America emphasized the importance of sharing research findings and safety concerns regarding CAMs with both HCPs and the public [

9]. The research underscores a prevalent misconception among consumers who believe CAMs are inherently safe due to their natural ingredients, cautioning that they can pose both direct and indirect harm [

9].

Moreover, a Malaysian study reported that 26% of CAM users experienced adverse events [

10], whereas a study conducted in the United Kingdom identified 45.8% of consumers reporting adverse events related to CAMs use [

11]. Underreporting of CAM-related adverse events is common. Braun et al. found that only 19% of participants reported adverse events [

12], and Barnes et al. highlighted differences in reporting adverse events between CAMs and non-CAMs [

13]. Factors contributing to this variation in adverse events across different parts of the world, include perceptions of CAMs safety, unsupervised usage, and limited awareness of reporting requirements [

14].

In Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) oversees the monitoring of the safety of medicines and relies on the reporting of adverse events to improve patient safety. While it is mandatory for pharmaceutical companies to report all serious adverse reactions suspected of being related to their medicines, reporting by health professionals has traditionally been voluntary. Health professionals and consumers can report adverse events of medicines to the TGA via email, fax, mail, or online forms [

15]. The Expert Committee on Complementary Medicine in Australia raised several concerns regarding the safe, appropriate, and effective use of CAMs. Among these concerns was the necessity for both consumers and health professionals to access accurate, reliable, and independent information about CAMs. Additionally, there was a call for individuals to develop appropriate skills to interpret available information and discern between reliable and unreliable sources to allow HCPs to make informed decisions about the use of CAMs [

8].

Labels provide crucial information about these medicines, including the strength of the active ingredients, excipient details, dosage, potential side effects, and safety warnings [

16]. Evaluating the list of ingredients is essential in clinical decision-making and in considering the risks and benefits. Previous studies have primarily focused on the popularity, efficacy, adverse events, and consumer perspectives of CAM [

17,

18]. However, there is limited literature on consumer perception or the use of CAM labels. The specific attention given to labels as conduits for providing information and guiding consumers’ choices remains relatively understudied. This gap in the literature leaves unanswered questions about how effectively labels convey essential information about CAMs for consumers, including details about ingredients, potential interactions, and adverse events, as well as the subsequent reactions of consumers to this information.

Hence, this study aimed to investigate CAMs utilization in Melbourne, Australia, as well as consumers’ views on their effectiveness and adverse events. Moreover, it seeks to assess how labels influence CAMs usage, especially in terms of consumer comprehension, seeking more information, and consulting with HCPs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

The study received ethics approval from RMIT University Ethics Committee under project number 25543.

2.2. Study Design and Setting

A cross-sectional design was employed to gather data on participants’ attitudes and practices towards CAMs. To ensure an adequate sample size, recruitment was initiated through a multi-faceted approach. Participants were recruited over a two-week period from September 4th to 18th, 2022. Initially, recruitment efforts were launched on social media platforms, including on RMIT pharmacy Twitter group. Subsequently, project flyers were distributed, featuring a QR code and an online survey link. A $20 voucher incentive for one in five participants was prominently displayed on the flyers to encourage participation. These flyers were disseminated at various community pharmacies across Melbourne, Australia. Furthermore, a direct survey link was shared within personal and professional networks to enhance the diversity of the sample. Participants received an invitation letter that provided detailed information about the survey’s objectives, estimated completion time, and the advisory committee overseeing the project.

2.3. Study Participants

Inclusion criteria for participation required individuals to be at least 18 years old and current users of CAMs. Potential participants under the age of 18 or those who hadn’t used CAMs within the past 6 months were automatically excluded from the survey to ensure relevancy. All participants were from Melbourne, Australia.

2.4. Development of Questionnaire

An anonymous self-administered questionnaire was developed to collect data from pharmacy customers, utilizing both professional networks and the snowballing technique. The 29-item questionnaire comprises five primary sections: demographics; consumer perceptions regarding the safety and effectiveness of CAMs, as well as the reasons for using CAMs; experience with label warnings; adverse reactions associated with CAMs; as well as the reporting of such reactions. Before commencing the survey, a pilot study was conducted to assess the clarity and relevance of the questionnaire items. The primary objectives included evaluating the duration required to complete the survey and identifying potential sources of response bias. Six actively practicing pharmacists participated in this preliminary assessment by engaging with the survey instrument. To ensure diverse response types and efficient completion, a variety of question formats were employed, such as multiple choice, open-ended free text, and Likert-scale responses. For queries related to perceptions of CAMs’ efficacy, quality, side effects, and safety, respondents used a Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, where a score of 5 represented strongly agree and 1 denoted strongly disagree. Specifically, participants were presented with a series of statements and were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement using a Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. These statements included “complementary and alternative medicines are safer than prescription medications,” “complementary and alternative medicines are more effective than prescription medications,” “in general, complementary and alternative medicines are of good quality,” “complementary and alternative medicines generally do not have side effects,” “doctors, nurses, and pharmacists should recommend complementary and alternative medicines more often,” “for chronic medical conditions, I would prefer to take CAMs rather than a prescription medication,” and “for minor ailments, I would prefer to take CAMs than a prescription medication.” Please refer to the supplementary file for the full questionnaire.

2.5. Data Analysis

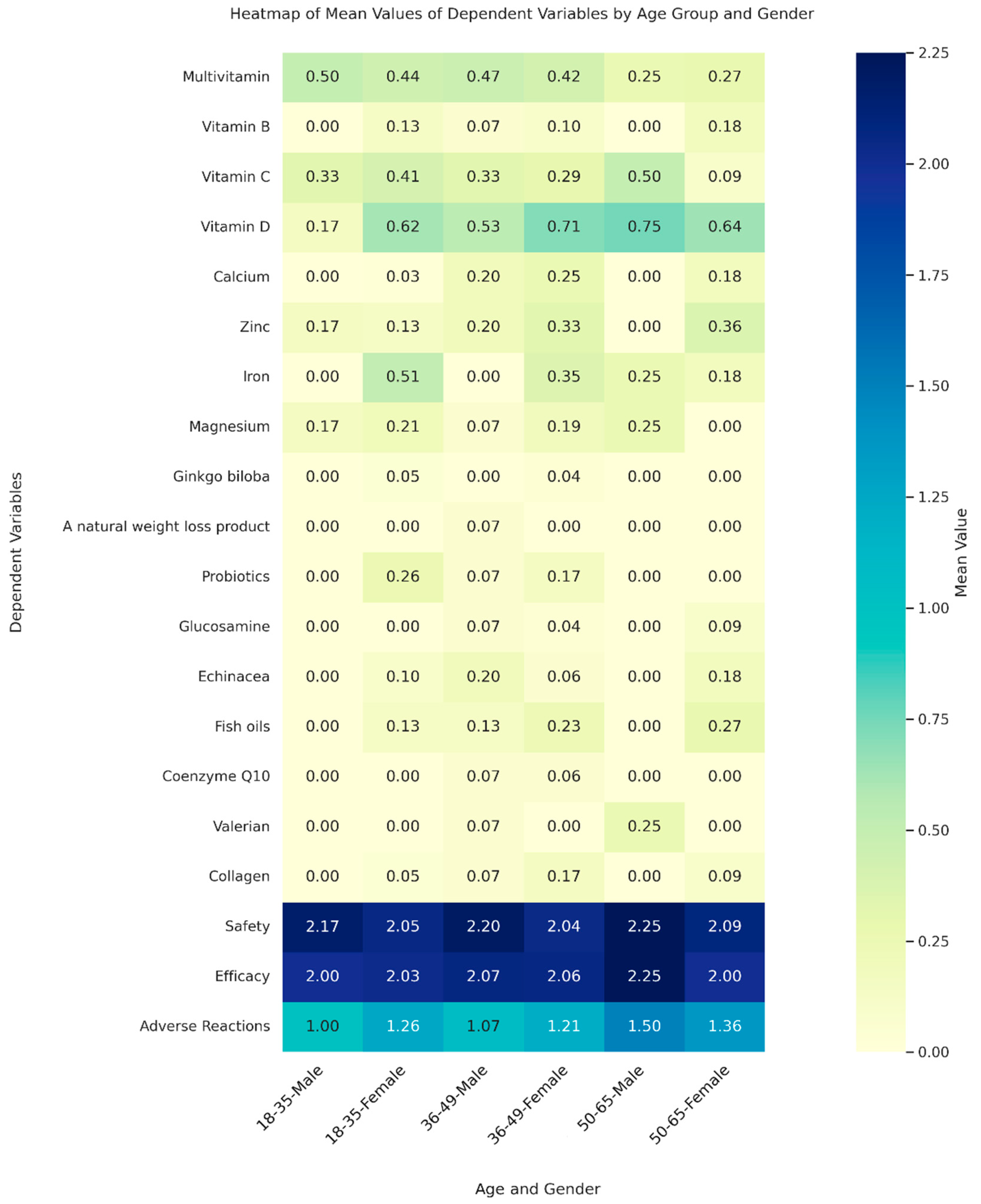

The collected data was analysed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Software (SPSS, Ver. 28). Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, were employed to analyse demographic characteristics and variables. Bivariate associations between dependent variables were examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. This comprehensive analysis allowed us to derive valuable insights into the relationships among the variables studied. Ordinal logistic regression was utilized to evaluate the influence of individual and grouped CAMs on age categories. For the purpose of this analysis, CAMs were categorized into three distinct groups: vitamins, which included multivitamins, Vitamin B, Vitamin C, and Vitamin D; minerals, comprising calcium, zinc, iron, and magnesium; and other CAMs, which encompassed a range of products such as Ginkgo biloba, natural weight loss products, probiotics, glucosamine, echinacea, fish oils, coenzyme Q10, St John’s Wort, valerian, and collagen. Additionally, binary logistic regression was employed to examine gender-based differences in CAMs usage. In addition, we used a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) to investigate how the joint effects of age and gender influence a range of dependent variables including different types of CAMs, and perceptions related to their safety, efficacy, and adverse reactions. The independent variables in MANOVA were age groups, divided into three categories: 18-35, 36-49, and 50-65 years, and gender, categorized into male and female. MANOVA was performed using the statsmodels library in Python, and the core visualization library matplotlib was utilized to create the heatmap illustrated in

Figure 1.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants Included in the Study

A total of 180 participants completed the online questionnaire, of which 125 participants responded to have been using CAMs. Demographic characteristics are described in

Table 1A.

The majority of participants 18 to 50 years of age (84.8%), with the highest percentage (48.8%) belonging to the 31–50-year age group. Females constituted a majority of the participants (79.2%). Education levels were varied, with 76.8% of participants having a university degree, 16% a diploma or certificate, and 7.2% having completed only high school education. A total of 44.8% of participants reported being in very good health, 31.2% indicated they were in good health, 17.6% rated their health as excellent, and 6.4% reported their health as poor. Additionally, 33.6% of participants reported currently taking prescription medicines. Participants used a diverse range of CAM products. Vitamin D was the most commonly used CAM, with 62.4% of participants reporting its use, followed by multivitamins at 40.8%, and both vitamin C and iron at 32% each. The consumers predominantly purchased CAM from pharmacies (88%) and supermarkets (24%).

Table 2B shows the primary sources through which respondents accessed information regarding CAMs. Notably, the internet/media emerged as the predominant source, with 37.1% (47) of the total respondents relying on this platform. Doctors were consulted by 30% (37) respondents, while pharmacists were consulted by 24% (31) respondents. Nineteen percent (24) of respondents sought advice from family and friends. In contrast, herbalists, the CAM labels, and other sources constituted smaller proportions, each representing less than 15% of respondents.

3.2. Insights into Participants’ Attitudes and Practices Related to CAMs

The survey revealed a variety of reasons why people use complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs). More than half of the respondents (54.8%) said they turn to CAMs to maintain their overall health and well-being. About one third (32.3%) use them as a preventive measure against disease, while 26.6% use CAMs to treat specific illnesses or symptoms. Nearly 30% (29.8%) mentioned that their choice to use CAMs was influenced by recommendations from healthcare professionals, friends, or family members. Smaller groups of participants feel that CAMs help them take control of their health (12.9%) or fit well into their lifestyle (10.5%). A very small number (3.2%) believe that CAMs work as well as, or even better than, regular medicines.

In response to whether label warning statements affected participants’ decision to take a product or prompted them to seek additional information, participants provided the following responses: 7 participants (5.7%) indicated that these warnings stopped them from taking the product. A larger group of 61 participants (48.8%) stated that the warnings led them to seek further information before using the product. On the other hand, 38 participants (30.4%) reported that, despite reading labels, they were not concerned by any warning. Interestingly, 13 participants (10.4%) admitted to not reading labels at all, and 3 participants (2.4%) acknowledged reading labels but facing difficulties in understanding them. The majority of participants (n=97, 77.6%) expressed they believed CAMs were safe, while 98 participants (78%) believed in their efficacy.

3.3. Adverse Reactions and Responses to CAMs

Among the study participants, 18.5% of participants reported encountering adverse reactions. The majority of those who experienced side effects identified the reactions as mild (66.7%), followed by moderate (25%), and a smaller portion as severe (8.3%). Interestingly, most of participants did not seek help from HCP and self-managed these adverse reactions. Notably, 33.3% ceased the use of the CAMs, while 25% decreased their dosage. Only 16.7% of participants sought advice from a HCPs after experiencing side effects. Interestingly, communication regarding adverse reactions were more likely to occur with doctors and family/friends (29.2% and 41.7%, respectively), while engagement with pharmacists (4.2%) was less frequent. Participants were prompted with an open-ended question to report any side effects they experienced, if applicable. Several participants mentioned experiencing diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and stomach-ache.

3.4. Correlations between Key Variables and CAMs Consumption

Table 3 presents correlations between key variables and CAMs consumption. There was a positive correlation between overall health status and the perceived effectiveness of CAMs (r = 0.43, p < 0.01). Additionally, participants’ perceptions of CAMs’ efficacy showed a positive correlation with their perceived effectiveness after usage (r = 0.48, p < 0.01). There was also a positive relationship between perceptions in CAMs’ quality and their perceived effectiveness (r = 0.41, p < 0.01). Furthermore, participants who held the view that CAMs were more effective than prescription medications demonstrated a moderate positive correlation with the perceived efficacy of CAMs (r = 0.36, p < 0.01). Additionally, people who used CAMs for minor health issues tended to believe that these products were of higher quality (r = 0.19, p < 0.05).

3.5. Demographic Trends in CAMs Usage and Perceptions

The MANOVA indicated that age and gender do not generally have a significant impact on the dependent variables (

p > 0.05), according to most test statistics. However, Roy’s greatest root test indicated potential effects of age and gender that might be worth further investigation, yielding significant p-value for age (

p = 0.01) and marginally significant for gender (

p = 0.06,

Figure 1). The ordinal logistic regression analysis showed a significant association between calcium consumption and higher age groups (coefficient = 1.658,

p = 0.006), indicating a higher tendency for older adults to use calcium supplements. In the binary logistic regression analysis, a significant gender-based pattern was observed in iron consumption, with females showing higher consumption (coefficient = 2.177,

p = 0.007).

4. Discussion

The findings from this study collectively underscore the multifaceted nature of factors influencing the utilization of CAMs, presenting a better understanding of consumer attitudes and practices.

Majority of CAMs users (48.8%) who participated in this study reported being attentive to product labels, and label warnings in most cases prompted them to seek further information or advice before using the products. This reflects a heightened awareness among consumers of potential safety concerns associated with CAMs. Interestingly, while a third of consumers (30.4%) indicated that they read the product label information, label warnings did not lead them to discontinue use or seek additional information from HCPs. A smaller fraction of consumers (10.4%) did not read or comprehend the labels (2.4%). The diverse responses received from the study participants highlighted the importance of enhancing consumer education and label clarity to foster safer CAMs use practices. It should be noted that majority of participants in this study held a university degree and that these data may been not representative of general population. Therefore, a large-scale study across different educational and socioeconomic levels is warranted to further explore the impact of label warning and label content on CAMs usage.

Another noteworthy finding is the limited involvement of HCPs, particularly pharmacists, in offering advice about CAMs. Although most CAMs users purchase their products from pharmacies, only a fraction of participants sought consultation with pharmacists regarding CAMs-related information and adverse effects. It has been noted in this study that nearly 30% of patients do not heed advice despite label warnings or fail to read the label warnings (10%).

Furthermore, Roy’s greatest root test [

19], which is used to assess the maximum canonical correlation between groups, brings attention to specific demographic nuances that might be overlooked in the general analysis. This test highlights that age significantly influences the outcomes (p = 0.01) and suggests a near-significant impact of gender (p = 0.06). These results indicate that these factors could play a critical role in specific conditions or among particular subgroups. This emphasizes the importance of further study on how these demographic characteristics influence perceptions and use of CAMs. Understanding these nuances could help us develop more focused health communication and intervention strategies.

The regression analysis offered valuable insights into how different demographics consume CAMs. We found that older adults are more likely to use calcium supplements, which makes sense given their need to maintain bone health as they age (coefficient = 1.658, p = 0.006). Similarly, the analysis showed that women are more likely to take iron supplements (coefficient = 2.177, p = 0.007). This aligns with the well-known fact that women, have higher iron requirements due to menstruation [

20]. Complementing these findings, the MANOVA results indicated that age and gender do not generally have a significant impact on the dependent variables, with a few exceptions noted. Specifically, Roy’s greatest root test suggested potential effects worth further investigation. This comprehensive approach helped gain a deeper understanding of how different demographic factors influence CAMs consumption patterns. It provided valuable insights into trends that could benefit from targeted interventions or further research. For instance, older adults tend to use supplements such as calcium more frequently, indicating a possible increase in CAMs usage as people age. Similarly, perceptions of safety and efficacy showed variation, although not significant, often correlating with higher usage rates. These findings highlight the need for further research to explore the differences more deeply.

A qualitative study conducted in Ontario, Canada reported that, the majority of consumers are unable to find healthcare providers who could adequately address their inquiries about CAMs [

21]. This disconnection between perceived roles and the actual utilization of pharmacist’s knowledge and skills presents an opportunity to bridge this gap by promoting pharmacists as dependable sources of CAMs information. Drawing on the knowledge of pharmacists to provide evidence-based advice on CAMs, prescription drug interactions and adverse effects, pharmacists are well-positioned to greatly improve the safe use of CAMs [

22]. However, it is important to note that pharmacists in Australia have expressed a lack of confidence in their knowledge of CAMs, which might impede their effective engagement with patients in providing comprehensive information about CAMs [

23]. Ensuring proper training and continuous education on CAMs for community pharmacists is essential to instil the confidence needed to approach patients and address their questions and concerns about CAMs. This recommendation echoed that of another study highlighting the need to have additional education and training for pharmacists to increase their knowledge and confidence [

24].

The analysis of participants’ beliefs regarding CAMs effectiveness in comparison to prescription medications is thought-provoking. Whilst a substantial proportion (15.8%) of consumers believed CAMs are more effective than prescription medications, almost half (41.6%) perceived CAMs as less effective than prescription medications. This contradicts previous findings that highlighted the importance of CAMs over prescribed medications [

3]. The difference could be attributed to the higher education levels of participants in this study, with all participants in this study having completed high school or tertiary level education, compared to 72.6% with primary education only and 11.2% with no formal education in the previous study. This finding underscores the role of consumer education level in shaping perceptions of CAMs in relation to conventional medications.

The results of this study also shed light on the CAMs related adverse reactions experienced by participants. It is notable that 18.5% of participants reported encountering adverse reactions. This finding challenges the common notion that CAMs are devoid of side effects, emphasizing the importance of acknowledging potential risks associated with these products [

25]. The majority of reported adverse reactions were categorized as mild (66.7%), with moderate reactions accounting for 25% and a smaller proportion classified as severe (8.3%). Similarly, a cross-sectional study conducted in England found that almost 50% of the study participants using CAMs reported encountering adverse events [

11]. These adverse effects were primarily of a mild to moderate nature, with only few serious or life-threatening [

11].

Interestingly, participants in this study demonstrated a trend towards self-management when faced with adverse reactions. It is noteworthy that 33.3% of participants discontinued the use of the CAMs upon encountering adverse reactions, while 25% chose to decrease their dosage. This inclination towards self-adjustment could indicate that consumers perceive themselves as the primary decision-makers in managing their health-related experiences. At the same time, it raises questions about the adequacy of information provided to consumers about potential side effects and their appropriate responses. Additionally, the study reveals that participants gather information about CAMs from various sources, with the internet and media playing a significant role. Alarmingly, 37.1% of respondents relied on the internet for information. These findings raise concerns regarding the quality of CAMs information available online. A previous review of Wikipedia entries on popular herbal supplements found significant gaps in crucial information, including details on drug interactions, effects during pregnancy, and contraindications [

26]. Moreover, the writing level of the entries exceeded the recommended comprehension level for readers [

26]. Additionally, 13 websites related to common herbal supplements lacked important safety information and failed to recommend consulting HCPs before using the products [

26]. These findings underscore the potential risks associated with relying solely on online sources for CAMs-related information. This underscores the influence of media in shaping individuals’ perceptions and decisions related to CAMs and highlights the need for HCPs to play a more active role in guiding consumers due to the potential risks associated with inappropriate CAMs use.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

We acknowledge the limitations in generalizability due to the demographic profile of participants, which may not fully represent the wider population of CAMs users, potentially skewing the results. The reliance on self-reported data and a cross-sectional design limits the establishment of causal relationships. Additionally, the small sample size limits the statistical power and generalizability of our findings. The study has a greater proportion of users for vitamins and minerals which limits the generalizability to other CAMs. Future research should employ longitudinal studies to investigate causal relationships and changes in CAMs usage over time and should recruit more diverse populations to better understand varied consumer behaviours, experiences, and perceptions. Nevertheless, this study highlighted the need for further research to further validate these insights. Moreover, qualitative research could offer deeper understanding of participants’ motivations, barriers, and experiences related to CAMs usage, label warnings, and pharmacist consultation.

6. Impact on Policy and Practice

This study underscores the need for enhanced regulatory and educational initiatives related to the use of CAMs. Our findings point to the necessity of clearer labelling practices, which should include detailed information on potential risks and interactions associated with CAMs. Moreover, establishing a standard system for reporting adverse reactions is essential for enhancing the monitoring of CAMs safety. Additionally, pharmacists and other HCPs require specialized training to engage with consumers regarding CAMs use, bridging the current gap in consumer education and safety. This approach could significantly improve the integration of CAMs into healthcare, ensuring that their use is both safe and well-informed.

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study examined various facets of CAMs usage, including label warnings and consumer beliefs, contributes to a better understanding of CAMs consumption patterns. The findings emphasize the need for targeted efforts to improve label comprehension, promote pharmacist consultation, and enhance consumer education about CAMs. Ultimately, fostering informed decision-making in CAMs usage can contribute to safer practices and better outcomes for consumers. This study also highlights the need for larger studies to gather more information on CAMs label usage and appropriateness, while policy changes should aim for stricter labelling standards and enhance pharmacist education to fill the existing gaps in knowledge about CAMs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Pegah Niyazmand, Maryam Hasmat, Debajan Ghafari, and Tores Avraha for their dedicated efforts in recruiting participants, which were crucial for gathering the data necessary for this research. We also extend our appreciation to Ali Alaraji for his insightful review of the survey questions and significant contributions to the development of the survey. Their hard work, commitment, and expertise greatly enhanced the quality of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, E.L.; Richards, N.; Harrison, J.; Barnes, J. Prevalence of Use of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the General Population: A Systematic Review of National Studies Published from 2010 to 2019. Drug Saf. 2022, 45, 713–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, A.; McIntyre, E.; Harnett, J.; Foley, H.; Adams, J.; Sibbritt, D.; Wardle, J.; Frawley, J. Complementary medicine use in the Australian population: Results of a nationally-representative cross-sectional survey. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijazi, M.A.; Shatila, H.; Omeich, Z.; El-Lakany, A.; Ela, M.A.; Naja, F. The role of pharmacists in complementary and alternative medicine in Lebanon: users’ perspectives. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shraim, N.Y.; Shawahna, R.; Sorady, M.A.; Aiesh, B.M.; Alashqar, G.S.; Jitan, R.I.; Abu Hanieh, W.M.; Hotari, Y.B.; Sweileh, W.M.; Zyoud, S.H. Community pharmacists’ knowledge, practices and beliefs about complementary and alternative medicine in Palestine: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ung, C.O.L.; Harnett, J.; Hu, H. Community pharmacist's responsibilities with regards to traditional medicine/complementary medicine products: A systematic literature review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2017, 13, 686–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popattia, A.S.; Hattingh, L.; La Caze, A. Improving pharmacy practice in relation to complementary medicines: a qualitative study evaluating the acceptability and feasibility of a new ethical framework in Australia. BMC Med Ethic- 2021, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walji, R.; Boon, H.; Barnes, J.; Welsh, S.; Austin, Z.; Baker, G.R. Reporting natural health product related adverse drug reactions: is it the pharmacist’s responsibility? Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 19, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Information Use and Needs of Complementary Medicines Users, 2008 available from: Microsoft Word - Information Use and Needs of Complementary Medicines Users 08121001.doc (westernsydney.edu.au).

- Ventola CL: Current Issues Regarding Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in the United States: Part 2: Regulatory and Safety Concerns and Proposed Governmental Policy Changes with Respect to Dietary Supplements. P t 2010, 35, 514-522.

- Werneke, U.; Earl, J.; Seydel, C.; Horn, O.; Crichton, P.; Fannon, D. Potential health risks of complementary alternative medicines in cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 90, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.S.A.; Aziz, Z. Complementary and alternative medicine: Pharmacovigilance in Malaysia and predictors of serious adverse reactions. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2020, 45, 946–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, N.; Winit-Watjana, W.; Baquir, W.; McGarry, K. Disclosure and adverse effects of complementary and alternative medicine used by hospitalized patients in the North East of England. Pharm. Pr. (Internet) 2012, 10, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Braun, L.; Tiralongo, E.; Wilkinson, J.M.; Poole, S.; Spitzer, O.; Bailey, M.; Dooley, M. Adverse reactions to complementary medicines: the Australian pharmacy experience. Int. J. Pharm. Pr. 2010, 18, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, J.; Mills, S.Y.; Abbot, N.C.; Willoughby, M.; Ernst, E. Different standards for reporting ADRs to herbal remedies and conventional OTC medicines: face-to-face interviews with 515 users of herbal remedies. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1998, 45, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.J. Adverse event monitoring and multivitamin-multimineral dietary supplements. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 323S–324S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.H.; Lucas, C. Reporting adverse drug events to the Therapeutic Goods Administration. Aust. Prescr. 2021, 44, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses, G. What’s in complementary medicines? Aust Prescr 2019, 42, 82–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.P.; A Cheras, P. The other side of the coin: safety of complementary and alternative medicine. The Medical Journal of Australia 2004, 181, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, I.M.; Nadler, B. Roy’s largest root test under rank-one alternatives. Biometrika 2017, 104, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbaspour, N.; Hurrell, R.; Kelishadi, R. Review on iron and its importance for human health. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shahin, W.; Kennedy, G.A.; Cockshaw, W.; Stupans, I. The effect of acculturation and harm beliefs on medication adherence on Middle Eastern hypertensive refugees and migrants in Australia. Pharm. Weekbl. 2021, 43, 1283–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilper, A.; Müller, A.; Huber, R.; Reimers, N.; Schütz, L.; Lederer, A.-K. Complementary medicine in orthopaedic and trauma surgery: a cross-sectional survey on usage and needs. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuerger, N.; Klein, E.; Hapfelmeier, A.; Kiechle, M.; Brambs, C.; Paepke, D. Evaluating the Demand for Integrative Medicine Practices in Breast and Gynecological Cancer Patients. Breast Care 2018, 14, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, H.S.; Kachan, N. Natural health product labels: is more information always better? Patient Educ Couns 2007, 68, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semple, S.J.; Hotham, E.; Rao, D.; Martin, K.; Smith, C.A.; Bloustien, G.F. Community pharmacists in Australia: barriers to information provision on complementary and alternative medicines. Pharm. World Sci. 2006, 28, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijazi, M.A.; Shatila, H.; El-Lakany, A.; Ela, M.A.; Kharroubi, S.; Alameddine, M.; Naja, F. Beliefs, practices and knowledge of community pharmacists regarding complementary and alternative medicine: national cross-sectional study in Lebanon. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).