1. Introduction

1.1. Leveraging Bacterial Omics Data for Pathogenicity Insights and Public Health

In microbiology research, the vast availability of bacterial omics data is a crucial asset for exploring the diverse aspects of bacterial human pathogens. This wealth of information is instrumental in developing large-scale, in-depth research aimed at expanding our knowledge on omics pathogenicity determinants, critically enhancing public health surveillance and facilitating the development of novel therapeutic strategies. Utilization of bioinformatics to analyze these data has been key in uncovering mechanisms of infection and resistance in established pathogens [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Complete genome data is particularly advantageous for these studies due to the need for high accuracy and completeness in genome assembly [

7,

8,

9]. By integrating this molecular data with epidemiological and clinical information, we can develop a more complete picture of bacterial pathogenesis. Data-driven insights may also contribute to the development of important predictive models to uncover the pathogenic potential of newly identified bacterial strains [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

1.2. Current Challenges

Despite the advances in omics technologies, significant challenges remain in the annotation of bacterial pathogenicity. A primary challenge is managing the vast volumes of data generated, requiring robust analytical methods for accurate classification and interpretation. Indeed, there is currently no publicly accessible and curated database that categorizes bacterial strains based on their human pathogen potential. To construct their training sets, past studies that developed pathogenicity prediction tools classified their selected genomes in pathogenic to humans (HP) and non-pathogenic to humans (NHP) using predominantly two methods.

The first one involved retrieving the information from databases, such as the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [

17], Genomes Online Database [

18] and the Integrated Microbial Genomes [

19]. However, most of these annotations are no longer available. While the exact reasons for this are not explicitly stated in the available literature, concerns about the accuracy of pathogenicity labels and the difficulty in keeping up with the influx of new genomic data are plausible explanations. Other related databases which integrate comprehensive genomic data include BacDive [

20] and gcPathogen [

21]. Although these provide an extensive and high-quality genomic resource, they lack annotation on bacterial pathogenicity at the strain level and for complete genomes. In addition, BacDive provides a limited number of genomes with pathogenicity annotations with unclear criteria. Similarly, gcPathogen primarily relies on species-level classifications derived from government health organizations. As emphasized in [

22], pathogenicity is more accurately assessed at the subspecies level and can vary significantly even within serovars. Incorporating these pathogenicity assessments could then improve the utility of pathogen inventories for research and public health efforts.

The second and most recently used method is the application of an annotation-based pathogenicity labeling, by applying a set of rule-based criteria on genome metadata [

13,

14,

15]. This method is inherently adaptable, and the transparency afforded by the explicit criteria ensures that the process is verifiable. Moreover, its capacity to leverage available metadata broadens its analytical scope, enabling a more comprehensive exploration of bacterial genomes and thereby enriching pathogenicity research. By considering various types of information — such as isolation source, associated disease, sample type and known interactions with hosts — the method can provide a more nuanced understanding of which bacterial strains are HP or NHP. However, the guiding principle which was generally used in these works to establish the rule-based criteria was that any bacterium isolated from a diseased individual should be considered as HP, while those from healthy individuals or probiotic supplements should be considered NHP. Yet, isolating a bacterium from a diseased individual doesn't confirm it as the causative agent of the illness [

23]. For instance, a bacterium isolated from someone with a non-infectious condition, such as Crohn's disease, would be wrongly labeled as HP, despite not causing an infectious disease. Similarly, isolating a bacterium from a healthy individual does not automatically indicate that it is NHP. Erroneous assumptions in pathogenicity classification risk introducing bias, potentially leading to the oversight of genes or proteins that are critical for understanding bacterial pathogenicity or for developing prediction tools. Indeed, an automatic method based on keywords was used in the context of these works which, while useful, may lead to incorrect classifications due to lack of context interpretation. A commonly used database to retrieve genomic and related data in the field of infectious diseases from previously described studies was PAThosystems Resource Integration Center (PATRIC), currently BV-BRC [

24]. While this database includes clinical samples from diseased individuals, many samples are collected outside of clinical settings. Therefore, it is crucial to thoroughly inspect this data when drawing inferences from it.

1.3. Objectives of BacSPaD

BacSPaD (Bacterial Strains’ Pathogenicity Database) was developed to address these challenges by providing a rigorously curated database focused on the pathogenicity of bacterial strains. The integration of high-quality genomic data with detailed metadata from two reputable sources is supplemented by manual curation and scientific literature review to ensure the accuracy of pathogenicity annotations. By classifying bacterial genomes as HP or NHP based on consistent criteria, BacSPaD provides a valuable resource for researchers studying bacterial pathogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition

The data utilized in this work was primarily extracted from the BV-BRC database and supplemented with BioSample metadata from NCBI [

24], which provides comprehensive insights into specimen origins and phenotypic traits. We selectively sourced genomes from BV-BRC associated with a human host, marked as ‘good’ quality, fully sequenced (‘complete’) and added to the database (‘insertion date’) after January 1, 2017, in order to balance data quality and volume. Then, the corresponding metadata from NCBI’s BioSample was retrieved via the Entrez system.

2.2. Data Pre-Processing and Integration

During preprocessing and integration, we meticulously identified and curated relevant fields from both databases. The final set of combined fields and their corresponding description are shown in Supplementary Information:

Table S1. This step involved a detailed examination of metadata content, aligning common fields, and addressing discrepancies. For example, we resolved 8 instances where multiple NCBI BioSample entries corresponded to a single BV-BRC genome entry, possibly due to the submission of biological replicates or updated sample details. We assessed the metadata content to ensure each genomic record was unique and removed the redundant entries. A total of 11,368 genomes to be annotated according to pathogenicity were retrieved after these preprocessing steps. The resulting enriched dataset laid the groundwork for our ensuing analysis and systematic annotation. A summary of the steps applied for the preprocessing and labeling phase, including the number of filtered and resulting genomes after each step is detailed in Supplementary Information:

Figure S1. We also assigned the taxonomy information for each genome from species to phylum based on NCBI taxonomy [

26].

2.3. Quality Control

Following the annotation phase, a final high-quality selection step was performed. Labeled genomes were only kept if they showed over 90% completeness and less than 5% contamination, as confirmed using CheckM version v1.1.6 [

26]. Furthermore, we focused on primary pathogens, excluding entries associated with immunocompromised individuals. Exceptions were made if the species was listed in the FDA-ARGOS Database Wanted Organism List [

28]. A list of the identified immunocompromised keywords used to guide this selection is shown in Supplementary Information: List S1. To further ensure sequence quality, 4 entries were removed as their genomes contained more than 20 contigs. Genomes associated with genetic modifications were also excluded.

3. Results

3.1. Pathogenicity Annotation

Using a rule-based workflow, we systematically categorized bacterial strains as either HP or NHP, based on their association to infectious processes, or lack thereof. The categorization began with the extraction of metadata using keywords suggested by Naor-Hoffman et al. [

13], which facilitated the initial sorting.

However, a significant number of genomes were misclassified, necessitating an iterative process of keyword inclusion and exclusion to improve accuracy. This refinement process led to the development of more comprehensive and reliable keywords lists that guided subsequent manual reviews. These final lists are detailed in Supplementary Information: List S2, S3, S4 and S5.

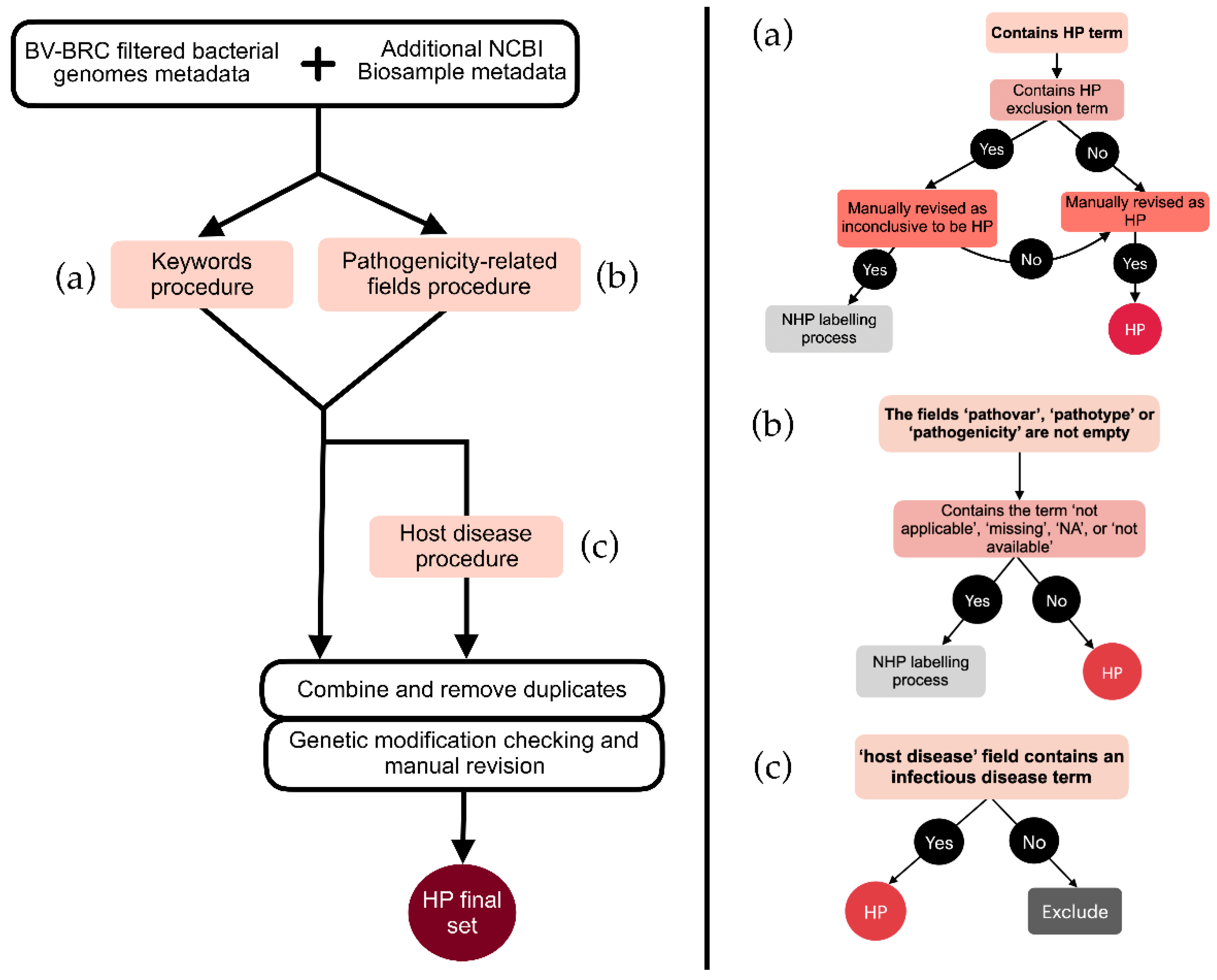

3.1.1. HP Labeling Workflow

An initial selection was performed based on keywords related to virulence, disease manifestations, and distinctive HP features (

Figure 1a). The final list of selected keywords was designated as ‘HP keywords’ (detailed in Supplementary Information: List S2). Conversely, keywords that usually correctly classified genomes as inconclusive were designated as ‘HP exclusion keywords’ (detailed in Supplementary Information: List S3). Genomes containing both an HP keyword and an HP exclusion keyword underwent a thorough review. If ambiguities remained, they were excluded from the HP category and reassessed under the NHP criteria. Ultimately, this process led to 4,343 genomes being labeled as HP.

Additional genomes were labeled as HP based on metadata fields directly suggesting pathogenicity, such as ‘pathovar’, ‘pathotype’, or ‘pathogenicity’ unless these fields were empty or marked with ‘not applicable,’ ‘missing,’ or ‘not available’ (

Figure 1b). In case they did, they would also be re-assessed under the NHP criteria. This process resulted in a total of 201 genomes labeled as HP.

In order to further assess and incorporate genomes of HP strains that were not labeled with the previous processes, we took advantage of the ‘host disease’ metadata field, which specifies the disease affecting the host from which the sample was obtained. Manual inspection was facilitated by the smaller number of unlabeled genomes (

Figure 1c). A total of 428 keywords related to documented infectious diseases were manually identified in this category (Supplementary Information:

Table S2). Genomes associated with any of these keywords were added to the HP set after removal of modified strains. This process resulted in a total of 1,046 genomes categorized as HP.

After combining the result of each of these steps, along with manual revision and filtering of mutant strains, a final set of 5,502 HP genomes was retrieved.

3.1.2. NHP Labeling Workflow

The NHP labeling process was initiated by excluding genomes already identified as HP (

Figure 2). Keywords associated with a NHP phenotype, designated as ‘NHP keywords

’, were also derived from extensive metadata review to ensure no association with disease (Supplementary Information: List S4). Then, a verification of keywords that were found to help detect inconclusive genomes was also followed and were designated as ‘NHP exclusion keywords’ (Supplementary Information: List S5). Lastly, a similar scrutiny for strains associated with genetic modification was applied to these NHP genomes, but in this case no such strain was found in this condition. This process led to a final set of 490 genomes being definitively categorized as NHP.

3.1.3. Manual Curation

The manual review involved a detailed examination of each genome’s classification, considering both the metadata and the latest scientific literature when necessary. Genomes with conflicting information—where metadata suggested a potentially NHP phenotype but was inconclusive, and literature indicated HP outcomes, or vice versa—were marked as inconclusive and were excluded from the dataset. This rigorous manual curation process ensured the reliability of our automated methods and the integrity of the final database.

3.2. Case Studies of HP and Inconclusive Genomes

Table 1 provides detailed examples of genomes categorized either as HP or inconclusive. For each genome, the table lists the most relevant metadata influencing their classification. The first two examples highlight scenarios where metadata contained both HP and exclusion keywords, necessitating a nuanced manual review to confirm their classification. For

Streptococcus pyogenes strain M75, although healthy volunteers are mentioned, researchers successfully caused them an infection using this strain [

29]. Similarly, for

Neisseria meningitidis strain S4, despite its species being described primarily as an obligate commensal, the metadata also states its “ability to cause septicemic disease and meningitis”, and that this strain in particular is an invasive strain.

3.3. Database Overview and Analysis

3.3.1. General Statistics and Distribution

We could annotate 5,992 complete and high-quality genomes according to their pathogenicity – 5,502 as HP (92%), and 490 as NHP (8%). This database encompasses a broad spectrum of bacterial taxa, including 532 species across 193 genera, 96 families, 53 orders, 26 classes, and 12 phyla. The main taxa and their proportions are illustrated in

Figure 3a. An interactive visualization of this figure may also be found in the web interface, enabling the visualization of all taxa.

Figure 3b illustrates the distribution of the 10 most prevalent families, highlighting Enterobacteriaceae as the most frequent family with 1,799 HP and 118 NHP genomes. Accordingly, this family predominantly consists of clinically significant organisms such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter. The second most frequent family is Alcaligenaceae (559 HP, 0 NHP), primarily due to the high prevalence of pathogenic strains of Bordetella pertussis, the agent responsible for whooping cough.

Other notable families include Mycobacteriaceae, Staphylococcaceae and Streptococcaceae, underscoring their clinical significance with a significant representation of HP genomes.

We also validated the comprehensive nature of our database against the FDA-ARGOS Database Wanted Organism List, and verified that there were at least two genomes per species for the priority pathogens.

Figure 3c displays the distribution of labeled genomes across all species featured in the list, with a minimum of 118 genomes for the top 10 species classified as HP. Specifically, the database includes 116 NHP genomes for this priority pathogens list: 83

Escherichia coli, 10

Klebsiella pneumoniae, 22

Staphylococcus aureus, and 1

Neisseria meningitidis.

Figure 3d presents a preview of the global map depicting the distribution of bacterial strains in the database based on their country of isolation. The color gradients represent the number of isolated strains, with darker shades indicating higher number. Countries with extensive public health surveillance and research infrastructure show higher numbers of isolated strains.

3.3.2. Virulence Factor Analysis

The analysis of virulence factors plays a pivotal role in identifying potential targets for drug development and assessing the risk of disease outbreaks. Although NHP strains can also harbor virulence genes, HP genomes are expected to contain a higher number of these factors. For a focused analysis, we selected a representative subset of 1,484 genomes from clinically relevant species, maintaining an HP to NHP ratio of approximately 11:1, consistent with the overall database distribution. The selected genomes were aligned against experimentally verified virulence factors from the Virulence Factor Database [

30] using Abricate v1.0.1 [

31] which uses BLAST and a subject coverage threshold of 80%. A total of 2,257 virulence factors were retrieved. Then, a chi-squared test with Yates' correction was conducted to evaluate the association between the presence of virulence factors and HP classification. The analysis confirmed a statistically significant association (X-squared = 5.523, df = 1, p-value = 0.019), with an odds ratio of 1.26, suggesting a moderate positive correlation between the presence of virulence factors and HP classification.

3.3.3. Database Structure

To support ongoing and future research endeavors, we have developed a web interface which can be accessed freely at

https://bacspad.altrabio.com/.

Data: Integrated dataset with pathogenicity annotation for each strain. Users can perform queries by any keyword across any field, as well as field-specific searches. Detailed descriptions of each metadata field are available in Supplementary Information:

Table S1. Users may download selected genomes or retrieve them in batch along various other data files such as proteomes and protein families from BV-BRC FTP site (

https://www.bv-brc.org/docs/quick_references/ftp.html). To facilitate the search for strains associated with a specific disease or isolation source category/subcategory, a categorization of diseases and isolation sources was also performed and the obtained fields added to this data. These were designated, respectively, as ‘disease category’, ‘disease subcategory’ and ‘isolation source’.;

Dashboard: This section features a range of statistical visualizations, including the top 10 and 50 species, the top 12 families, a location distribution map according to the country of isolation, and interactive visualizations of taxonomy, isolation sources and disease categories with respective subcategories.;

Molecular Biology: This section includes visualizations on the distributions for plasmids and contigs counts, genome lengths in base pairs (‘bp’), GC content percentage, and protein-coding sequences (‘PATRIC CDS’);

Virulence Factors: Virulence factor information for the most prevalent clinical species, including the gene name, the frequency at which it is found in HP strains, the frequency at which it is found in NHP strains, a list of the BV-BRC genome ids in which it is found, the species names, and the corresponding number of strains, species, genera and families;

About: Summary of the utility of BacSPad for microbiology research.

4. Discussion

A critical barrier in microbial genomics has been the absence of a comprehensive, publicly accessible database that categorizes bacterial strains by their pathogenic potential in humans. The reliability of computational pathogenicity studies and models hinges significantly on the quality of the training data used. Our database, developed through meticulous integration and manual review of extensive metadata, is designed to overcome this limitation. The NHP labeling of genomes from species usually regarded as HP, such as

Escherichia coli and

Klebsiella pneumoniae, highlights the necessity for nuanced strain-level pathogenicity classification. Despite efficiently processing vast databases, automated keyword matching often overlooks the subtleties in complex biological data. Our manual review process, informed by the latest scientific literature, provides a layer of qualitative analysis essential for capturing the multifaceted nature of bacterial pathogenicity. Host interactions, genetic variations, and environmental conditions are critical in determining a strain's pathogenic potential. Our case studies in

Section 3.3 illustrate the crucial role of metadata revision in precise pathogen classification and highlight the complexity of bacterial pathogenesis. In addition, the exclusion of genomes associated with genetic modifications is a crucial step that has generally not been addressed in previous studies and current resources. This step ensures that our database reflects the natural dynamics of bacterial infections, allowing for more accurate computational studies of bacterial pathogenicity. Results are not confounded by artificial genetic changes that may alter virulence properties. Moreover, by assessing important disease keywords from the ‘host disease’ metadata field, we were able to significantly increase the number of effectively labeled genomes. The further manual categorization of this field may also be of utility, mainly for researchers examining the disease associations of microbes and their specific pathogenic potential under varying health conditions.

Importantly, while the virulence factor analysis confirmed a statistically significant correlation between the amount of virulence factors and pathogenic classification, the moderate odds ratio of 1.26 suggests that the predictive power of known virulence factors is limited. This finding underscores the need for a more integrative and comprehensive approach to understanding bacterial pathogenicity, which BacSPaD aims to facilitate.

However, our database is not without limitations. The genetic basis of pathogenicity was not assessed during the annotation process, and the inclusion of antimicrobial resistance data could enrich the database's utility. The binary classification system—labeling genomes simply as HP or NHP—may not fully reflect the nuanced spectrum of bacterial pathogenicity. Future developments should consider a more sophisticated categorization system and ensure regular updates to the database to incorporate new genomes and re-evaluate classifications based on new research findings.

In conclusion, our database presents a robust and comprehensive integrated resource of bacterial pathogenicity at the strain level. Future research will benefit from using it to assess global and specific determinants of bacterial pathogenicity, in order to further enrich our understanding of this complex field. Researchers may uncover patterns and develop prediction tools more effectively. This advancement may, in turn, significantly impact public health efforts in mitigating the problem of infectious diseases.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: BacSPaD genome metadata fields and their corresponding description; Figure S1: Summary of the steps applied for the pre-processing phase, including filtration and refinement of bacterial genomes data and respective labeling phase; List S1: Final list of keywords associated with immunocompromised hosts; List S2: Final list of HP keywords; List S3: Final list of HP exclusion keywords; Table S2: Final list of infectious disease keywords and their frequency; List S4: Final set of NHP keywords; List S5: Final set of NHP exclusion keywords.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R., K.A., J.N.; Data curation, S.R.; Formal analysis, S.R. and G.C.; Funding acquisition, I.M. and L.B.; Investigation, S.R.; Methodology, S.R.; Project administration, J.N., J.-P.L. and L.B.; Resources, S.B. and L.B.; Software, G.C.; Supervision, J.-P.L., S.B. and L.B.; Validation, S.R.and S.B.; Visualization, S.R. and G.C.; Writing – original draft, S.R.; Writing – review & editing, S.R., K.A., J.N., L.S., I.M. and S.B.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 955626 within the PEST-BIN project; I.M. acknowledges funding from the Novo Nordisk Foundation, grant number NNF20CC0035580.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. .

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in BacSPaD web interface at

https://bacspad.altrabio.com/ and can be freely downloaded in CSV format.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the BV-BRC support team for their valuable clarifications and to the PEST-BIN consortium for their pertinent insights. .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Didelot, X.; Walker, A.S.; Peto, T.E.; Crook, D.W.; Wilson, D.J. Within-Host Evolution of Bacterial Pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 150–162.

- Tagini, F.; Greub, G. Bacterial Genome Sequencing in Clinical Microbiology: A Pathogen-Oriented Review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 2007–2020.

- Boolchandani, M.; D’Souza, A.W.; Dantas, G. Sequencing-Based Methods and Resources to Study Antimicrobial Resistance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 356–370.

- Subramanian, D.; Natarajan, J. Leveraging Big Data Bioinformatics Approaches to Extract Knowledge from Staphylococcus Aureus Public Omics Data. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 49, 391–413.

- Halawa, E.M.; Fadel, M.; Al-Rabia, M.W.; Behairy, A.; Nouh, N.A.; Abdo, M.; Olga, R.; Fericean, L.; Atwa, A.M.; El-Nablaway, M.; et al. Antibiotic Action and Resistance: Updated Review of Mechanisms, Spread, Influencing Factors, and Alternative Approaches for Combating Resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1305294.

- Nalpas, N.; Kentache, T.; Dé, E.; Hardouin, J. Lysine Trimethylation in Planktonic and Pellicle Modes of Growth in Acinetobacter Baumannii. J. Proteome Res. 2023, 22, 2339–2351.

- Ben Khedher, M.; Ghedira, K.; Rolain, J.-M.; Ruimy, R.; Croce, O. Application and Challenge of 3rd Generation Sequencing for Clinical Bacterial Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Jung, A.; Metzner, M.; Ryll, M. Comparison of Pathogenic and Non-Pathogenic Enterococcus Cecorum Strains from Different Animal Species. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 33.

- Fouts, D.E.; Matthias, M.A.; Adhikarla, H.; Adler, B.; Amorim-Santos, L.; Berg, D.E.; Bulach, D.; Buschiazzo, A.; Chang, Y.-F.; Galloway, R.L.; et al. What Makes a Bacterial Species Pathogenic?:Comparative Genomic Analysis of the Genus Leptospira. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004403.

- Cosentino, S.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Lund, O. PathogenFinder - Distinguishing Friend from Foe Using Bacterial Whole Genome Sequence Data. PLoS One 2013, 8, e77302.

- Andreatta, M.; Nielsen, M.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Lund, O. In Silico Prediction of Human Pathogenicity in the γ-Proteobacteria. PLoS One 2010, 5, e13680.

- Iraola, G.; Vazquez, G.; Spangenberg, L.; Naya, H. Reduced Set of Virulence Genes Allows High Accuracy Prediction of Bacterial Pathogenicity in Humans. PLoS One 2012, 7, e42144.

- Naor-Hoffmann, S.; Svetlitsky, D.; Sal-Man, N.; Orenstein, Y.; Ziv-Ukelson, M. Predicting the Pathogenicity of Bacterial Genomes Using Widely Spread Protein Families. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, 23, 253.

- Barash, E.; Sal-Man, N.; Sabato, S.; Ziv-Ukelson, M. BacPaCS—Bacterial Pathogenicity Classification via Sparse-SVM. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2001–2008.

- Deneke, C.; Rentzsch, R.; Renard, B.Y. PaPrBaG: A Machine Learning Approach for the Detection of Novel Pathogens from NGS Data. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39194.

- Wang, H.; Cui, W.; Guo, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhou, Y. Machine Learning Prediction of Foodborne Disease Pathogens: Algorithm Development and Validation Study. JMIR Med Inform 2021, 9, e24924.

- Kitts, P.A.; Church, D.M.; Thibaud-Nissen, F.; Choi, J.; Hem, V.; Sapojnikov, V.; Smith, R.G.; Tatusova, T.; Xiang, C.; Zherikov, A.; et al. Assembly: A Resource for Assembled Genomes at NCBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D73–D80.

- Mukherjee, S.; Stamatis, D.; Bertsch, J.; Ovchinnikova, G.; Sundaramurthi, J.C.; Lee, J.; Kandimalla, M.; Chen, I.-M.A.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Reddy, T.B.K. Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) v.8: Overview and Updates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D723–D733.

- Markowitz, V.M.; Chen, I.-M.A.; Palaniappan, K.; Chu, K.; Szeto, E.; Grechkin, Y.; Ratner, A.; Jacob, B.; Huang, J.; Williams, P.; et al. IMG: The Integrated Microbial Genomes Database and Comparative Analysis System. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D115–D122.

- Reimer, L.C.; Sardà Carbasse, J.; Koblitz, J.; Ebeling, C.; Podstawka, A.; Overmann, J. BacDive in 2022: The Knowledge Base for Standardized Bacterial and Archaeal Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D741–D746.

- Guo, C.; Chen, Q.; Fan, G.; Sun, Y.; Nie, J.; Shen, Z.; Meng, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; et al. gcPathogen: A Comprehensive Genomic Resource of Human Pathogens for Public Health. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D714–D723.

- Bäumler, A.; Fang, F.C. Host Specificity of Bacterial Pathogens. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013, 3, a010041.

- Falkow, S. Molecular Koch’s Postulates Applied to Microbial Pathogenicity. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1988, 10, S274–S276.

- Olson, R.D.; Assaf, R.; Brettin, T.; Conrad, N.; Cucinell, C.; Davis, J.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Dickerman, A.; Dietrich, E.M.; Kenyon, R.W.; et al. Introducing the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC): A Resource Combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D678–D689.

- Barrett, T.; Clark, K.; Gevorgyan, R.; Gorelenkov, V.; Gribov, E.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I.; Kimelman, M.; Pruitt, K.D.; Resenchuk, S.; Tatusova, T.; et al. BioProject and BioSample Databases at NCBI: Facilitating Capture and Organization of Metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D57–D63.

- Schoch, C.L.; Ciufo, S.; Domrachev, M.; Hotton, C.L.; Kannan, S.; Khovanskaya, R.; Leipe, D.; Mcveigh, R.; O’Neill, K.; Robbertse, B.; et al. NCBI Taxonomy: A Comprehensive Update on Curation, Resources and Tools. Database 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the Quality of Microbial Genomes Recovered from Isolates, Single Cells, and Metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055.

- Sichtig, H.; Minogue, T.; Yan, Y.; Stefan, C.; Hall, A.; Tallon, L.; Sadzewicz, L.; Nadendla, S.; Klimke, W.; Hatcher, E.; et al. FDA-ARGOS Is a Database with Public Quality-Controlled Reference Genomes for Diagnostic Use and Regulatory Science. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3313.

- Osowicki, J.; Azzopardi, K.I.; Fabri, L.; Frost, H.R.; Rivera-Hernandez, T.; Neeland, M.R.; Whitcombe, A.L.; Grobler, A.; Gutman, S.J.; Baker, C.; et al. A Controlled Human Infection Model of Streptococcus Pyogenes Pharyngitis (CHIVAS-M75): An Observational, Dose-Finding Study. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e291–e299.

- Chen, L.; Yang, J.; Yu, J.; Yao, Z.; Sun, L.; Shen, Y.; Jin, Q. VFDB: A Reference Database for Bacterial Virulence Factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, D325–D328.

- Seemann, T. Abricate. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/abricate (accessed on 10 May, 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).