Submitted:

10 July 2024

Posted:

11 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Assessment Instrument

2.3.1. For linguistic and Cultural Adaptation, the Validity Coefficient was Used

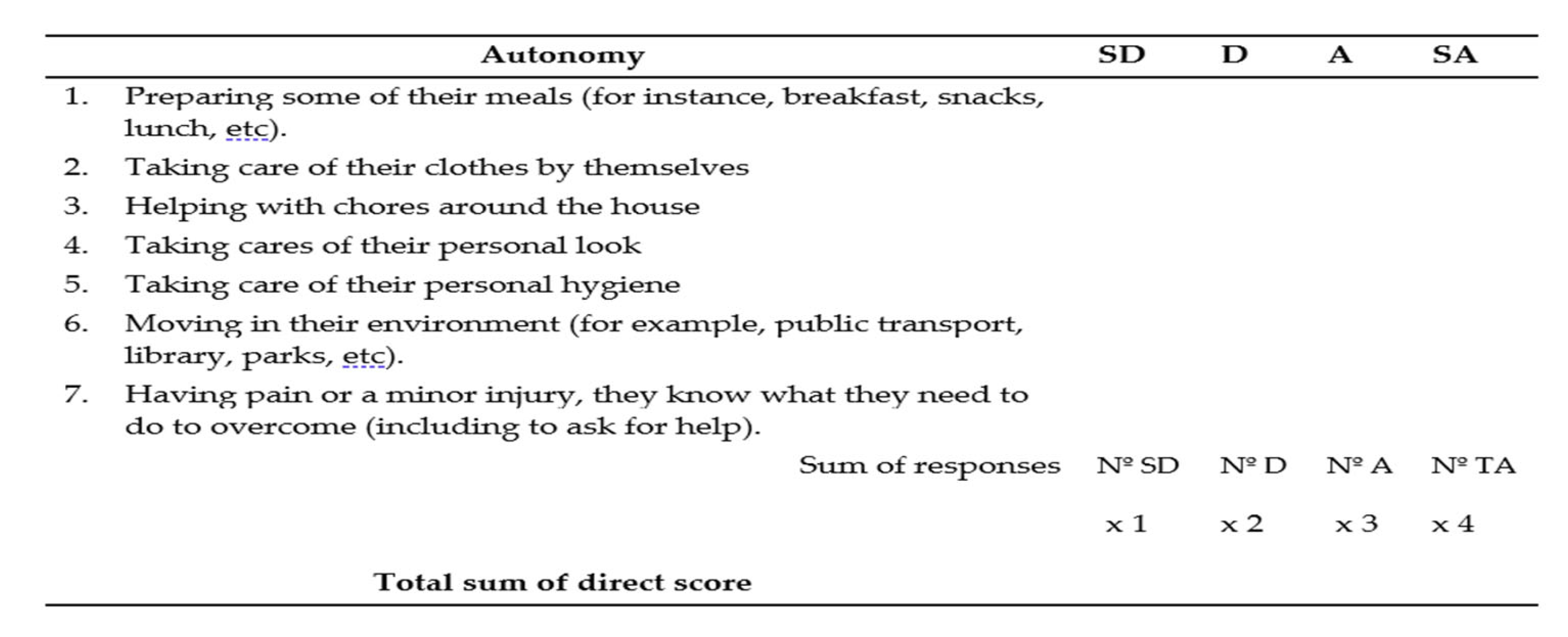

- Autonomy, composed of 7 items

- Self-initiation, composed of 6 items

- Self-direction, composed of 12 items

- Self-regulation, composed of 3 items

- Self-realization composed of 6 items, and

- Empowerment composed of 12 items.

2.4. Sociodemographic Data

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Results of Linguistic and Cultural Adaptation of the Scale AUTODDIS

- In the informant’s data section, changing the word Speech Therapist for Speech Pathologist and Health Services for Healthcare Services.

- In the data of the person assessment, the recommended changes were the following: autonomous community by region, primary education for elementary education, secondary education for high school education, funded for subsidized, ordinary classroom for regular classroom, vocational center for employment center, and assisted living facility for apartment.

- In the section of autonomy subscale in the section items, they recommended replacing the word snack for light meal. There are few changes as specified the Table 1.

| Category | Qualification | Indicator | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sufficiency Items that belong to one dimension are sufficient to have the measurement of it. |

1. It does not meet the criterion | Items are not enough to measure the dimension | |

| 2. Low level | Items measure few aspects of the dimension, but they do not correspond to the total dimension | ||

| 3. Moderate level | Some items must be aggregate to measure the dimension completely | ||

| 4. High level | Items are enough | ||

| Coherence The item has a logic relationship with the dimension or indicator which is measuring |

1. It does not meet the criterion | The item has not not logical relationship with the dimension | |

| 2. Low level | The item has a tangential relationship with the dimension | ||

| 3. Moderate level | The item has a moderate relationship with the dimension that is measuring | ||

| 4. High Level | The item is completely related to the dimension to measure. | ||

| Relevance The item is essential or fundamental, that is, it must be included |

1. It does not meet the criterion | The item, it can be eliminated without affecting the dimension measurement | |

| 2. Low level | The item it has some relevance, but another item is including what is measure | ||

| 3. Moderate level | The item is important | ||

| 4. High Level | It is a relevant item, and it should be included | ||

| Clarity The item can be easily understood. Its syntactic and semantic are adequate |

1. It does not meet the criterion | The item is not clear at all | |

| 2. Low level | The item requires quite a few modifications or a large modification in the use of the words according to their meaning or by the order of the same | ||

| 3. Moderate level | It is necessary a specific item modification or some of the item’s terms modification | ||

| 4. High Level | The item is clear in semantic and syntax |

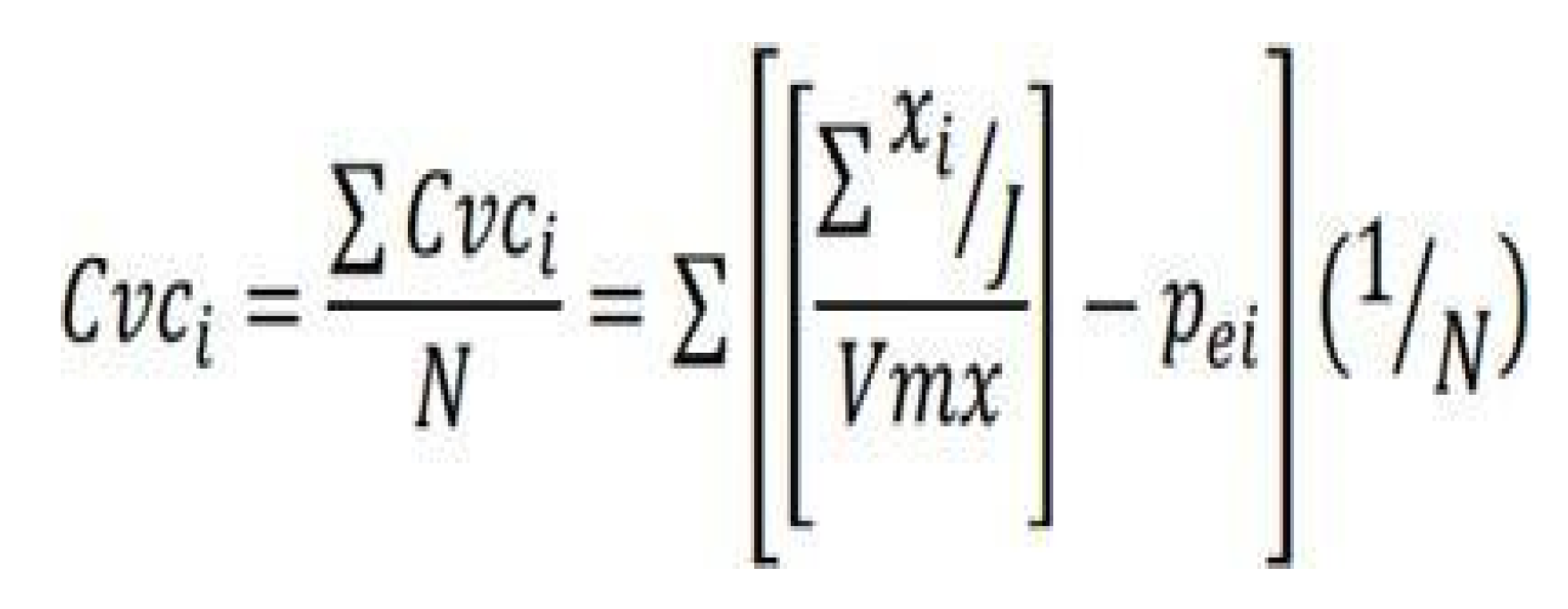

3.1.2. Content Validity Coefficient

| CVC | Assessment |

| <.60 | Unacceptable |

| ≥.60 | Deficient |

| >.71 y < .80 | Acceptable |

| > .80 y < .90 | Good |

| > .90 | Excellent |

3.2. Reliability, Internal Consistency Analysis

3.3. Descriptive Statistical Results of the General Scale

3.4. Descriptive Statistical Results for Each Subscale

3.5. Results Coefficient of Each Subscale

4. Discussion

Limitations, Strengths, and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nations U. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol. 2006. Disponible en línea: file:///C:/Users/Lenovo/Downloads/tccconvs.pdf (consultado el 28 de Mayo de 2024).

- Dinerstein RD. Implementing Legal Capacity Under Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: The Difficult Road From Guardianship to Supported Decision-Making. Human Rights Brief. 2012,19 (2), 8-12.

- Schalock RL, Luckasson RA, Tassé MJ. Defining, diagnosing, classifying, and planning supports for people with intellectual disability: an emerging consensus. Siglo Cero Revista Española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual. 2021, 52(3),29-36. [CrossRef]

- Van Loon J. Autodeterminación para todos. La autodeterminación en Arduin. Revista española sobre discapacidad intelectual. 2012,37,35 – 46.

- Wehmeyer ML. The Arc's Self-Determination Scale. Procedural Guidelines. United States, 1995, 1-129.

- Walker HM, Calkins C, Wehmeyer ML, Walker L, Bacon A, Palmer SB, et al. A Social-Ecological Approach to Promote Self-Determination. Exceptionality. 2011,19(1), 6-18. [CrossRef]

- Arellano AA; Peralta F. Autodeterminación de las personas con discapacidad intelectual como objetivo educativo y derecho básico: estado de la cuestión. Revista Española de Discapacidad. 2013,1 (1), 97-117. [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer ML. Self-Determination and Individuals with Severe Disabilities: Re-examining Meanings and Misinterpretations. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2005, 30, 113-20. [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer ML. The Importance of Self-Determination to the Quality of Life of People with Intellectual Disability: A Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17(19). [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer ML. Self-Determination and Mental Retardation. Revista internacional de investigaciones sobre retraso mental. 2001,24, 1-48.

- Wehmeyer L; Kelchner K; Richards S. Essential Characteristics of Self Determined Behavior of Individuals With Mental Retardation. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1996, 100, 6, 632-642.

- Verdugo MA; Sánchez, E; Gómez, M; Fernández, R; Wehmeyer, ML; Badia Corbella, M; González GF; Calvo Álvarez, MI. Escala ARC-INICO de Evaluación de la Autodeterminación. Manual de aplicación y corrección. Instituto Universitario e Integración a la comunidad: Salamanca, España,2014.

- Shogren KA; Wehmeyer, ML; Palmer, SB; Forber-Pratt, AJ; Little, TJ; Lopez, S. Causal Agency Theory: Reconceptualizing a Functional Model of Self-Determination. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 2015, 50, 3, 251-63.

- Shogren KR; Raley SK. Self-Determination and Causal Agency Theory. Integrating Research into Practice. Positive Psychology and Disability Series. Springer Nature Switzerland: Laurence Kansas, 2022 pág. 1-149.

- Vicente E; Mumbardó-Adam C; Guillén VM; Coma-Rosello T; Bravo-Alvarez MA; Sánchez S. Self-Determination in People with Intellectual Disability: The Mediating Role of Opportunities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17(17).

- Mumbardó AC; Sánchez E; Giné C; Guardia J; Raley SK; Verdugo MA. Promoviendo la autodeterminación en el aula: el modelo de enseñanza y aprendizaje de la autodeterminación. Siglo Cero Revista Española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual. 2018, 48(2).

- Palmer SB; Wehmeyer ML; Shogren KA. The Development of Self-Determination During Childhood. In: Wehmeyer ML, Shogren KA, Little TD, Lopez SJ, editors. Development of Self-Determination Through the Life-Course. Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. págs. 71-88.

- Raley SK; Shogren KA; Rifenbark GG; Anderson MH; Shaw LA. Comparing the Impact of Online and Paper-and-Pencil Administration of the Self-Determination Inventory: Student Report. Journal of Special Education Technology. 2019, 35(3), 133-44.

- Pérez MP. Aportes de la educación musical a las personas con discapacidad visual en la promoción de la autodeterminación. Ricercare. 2020, 13, 3-25.

- Álvarez-Aguado I; Vega V; González SH; González-Carrasco F; Jarpa M; Campaña K. Autodeterminación en personas con discapacidad intelectual que envejecen y algunas variables que inciden en su desarrollo. Interdisciplinaria Revista de Psicología y Ciencias Afines. 2021, 38(3),139-54.

- Vicente E; Pérez-Curiel P; Mumbardó AC; Guillén VM; Bravo-Alvarez MA. Personal Factors, Living Environments, and Specialized Supports: Their Role in the Self-Determination of People with Intellectual Disability. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023, 13(7).

- Wehmeyer ML; Metzler, CA. How Self -Determined Are People With Mental Retardation? The National Consumer Survey. Mental Retardation. 1995, 33, 111-9.

- Schalock R; Verdugo, MA; Jenaro, C; Wang, M; Wehmeyer, M; Jiancheng, X; Lachapelle, Y. Cross-Cultural Study of Quality of Life Indicators. American Journal On Mental Retardation. 2005,110, 4, 298–311.

- Lachapelle Y; Wehmeyer ML; Haelewyck MC; Courbois Y; Keith KD; Schalock R; et al. The relationship between quality of life and self-determination: an international study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2005, 49(Pt 10):740-4.

- Santamaría M; Verdugo MA; Orgaz, B; Gómez, LE; De Urríes, FDB. Calidad de vida percibida por trabajadores con discapacidad intelectual en empleo ordinario. Siglo Cero: Revista Española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual.2012, 43(242),46-61.

- Castro L; Cerda G; Vallejos V; Zúñiga D; Cano R. Calidad de vida de personas con discapacidad intelectual en centros de formación laboral. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana. 2016, 34(1), 175-86.

- Gómez M; Verdugo MA. El cuestionario de evaluación de la calidad de vida de alumnos de educación secundaria obligatoria: descripción, validación inicial y resultados obtenidos tras su aplicación en una muestra de adolescentes con discapacidad y sin ella. Siglo Cero: Revista Española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual.2004,35(212), 5-17.

- Vega V; ÁLvarez-Aguado I; González H; González F. Avanzando en autodeterminación: estudio sobre las autopercepciones de personas adultas con discapacidad intelectual desde una perspectiva de investigación inclusiva. Siglo Cero Revista Española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual. 2020, 51(1).

- Muñoz-Cantero JM & Losada-Puente L. Validación del constructo de autodeterminación a través de la escala ARC-INICO para adolescentes. Revista Española de Pedagogía. 2019, 77(272), 43-62.

- Verdugo MA; Sánchez, E; Guillén, VM; Sánchez, S; Ibáñez, A; Fernández, R; Vived, E. Escala AUTODDIS: Evaluación de la autodeterminación de jóvenes y adultos con discapacidad intelectual. Manual de aplicación y corrección. Instituto Universitario e Integración a la comunidad: Salamanca, España, 2021; pág 1-86.

- Vicente E; Verdugo MA; Guillén VM; Martinez-Molina A; Gómez LE; Ibañez A. Advances in the assessment of self-determination: internal structure of a scale for people with intellectual disabilities aged 11 to 40. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2020,64(9),700-12.

- Verdugo MA; Vicente E; Guillen VM; Sanchez S; Ibanez A; Gomez LE. A measurement of self-determination for people with intellectual disability: description of the AUTODDIS scale and evidences of reliability and external validity. Int J Dev Disabil. 2023,69(2),317-26.

- Vicente E.; Guillén VM; Fernández-Pulido R; Bravo MA; Vived E. Avanzando en la evaluación de la Autodeterminación: diseño de la Escala AUTODDIS. Aula Abierta. 2019,48(3),301-10.

- Vicente E; Guillén VM; Gomez LE; Ibañez A; Sánchez S. What do stakeholders understand by self-determination? Consensus for its evaluation. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019,32(1),206-18.

- Galicia LA; Balderrama JA; Edel R. Content validity by experts judgment: Proposal for a virtual tool. Apertura 2017,9(2),42-53.

- Hernández-Nieto RA. Contributions to Statistical Analysis: The Coefficients of Proportional Variance, Content Validity and Kappa; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2002; págs 100-228.

- Frías-Navarro, D. Apuntes de estimación de la fiabilidad de consistencia interna de los ítems de un instrumento de medida. Universidad de Valencia. Valencia, España, 2022. https://www.uv.es/friasnav/AlfaCronbach.pdf (revisado 6 de junio 2024).

- Hernández R; Fernández, C; Baptista, P. Metodología de la investigación, cuarta ed.; McGraw-Hill: México, México, 2014; pág.102-256.

- Chiner E. Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, España. Materiales docentes de la asignatura Métodos, Diseños y Técnicas de Investigación Psicológica, 2011.

- Escobar J; Cuervo Á. Validez de contenido y juicio de expertos: una aproximación a su utilización. Avances en medición. 2008,6,27-36.

- Álvarez-Aguado I; Vega-Córdova V; Campaña-Vilo K; González-Carrasco F; Spencer-González H; Arriagada-Chinchón R. Habilidades de autodeterminación en estudiantes chilenos con discapacidad intelectual: avanzando hacia una inclusión exitosa. Revista Colombiana de Educación. 2020,79,369-94.

- Peralta F; Alquegui, B; Arteta, R; Landa, M; Santesteban, I. Intervención para el desarrollo de la autoconsciencia en alumnos con retraso mental: propuesta de actividades. Revista Española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual. 2004,35(3),18-30.

- Tamarit J; Espejo, L. Experiencias de empoderamiento de personas con discapacidad intelectual o del desarrollo. Siglo Cero: Revista Española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual. 2013,44(246):26-39.

- Vicente E; Mumbardó-Adam, C; Coma, T; Gine, C; Alonso, V. Autodeterminación en personas con discapacidad intelectual y del desarrollo: revisión del concepto, su importancia y retos emergentes. Revista Española de Discapacidad. 2018, 6(2),7-25.

- Arellano A; Peralta F. Self-determination of young children with intellectual disability: understanding parents' perspectives. British Journal of Special Education.2013, 40(4),175-81.

- Losada-Puente L.; Muñoz JM. Validación del constructo de autodeterminación a través de la escala ARC-INICO para adolescentes. Revista Española de Pedagogía. 2019, 272, 143-162.

- Mithaug DE. Equal Opportunity Theory; SAGE PublicationsThousand Oaks. EEUU, 1996; pág.

- Murte PA. Diseño de un programa de formación para la transición a la vida adulta en personas con discapacidad intelectual: uso del dinero a través de la autorregulación. Nivel Master, Universidad de Almaría, España, 5 de marzo,2012.

- Cruz-Velandia I. ; Hernandez J. Exclusión social y discapacidad; Editorial Universidad del Rosario: Bogota, Colombia, 2006; págs. 210.

- Rozo Reyes CM; Monsalve AM. Discapacidad y justicia distributiva: una mirada desde la bioética. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría. 2011, 40(2):336-51.

| Cronbach’s Alpha | N° elements |

| .978 | 46 |

| Subscale | Cronbach’s Alpha | Nº of elements |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | .941 | 7 |

| Self-initiation | .925 | 6 |

| Self-direction | .970 | 12 |

| Auto-regulation/Adjustment | .804 | 3 |

| Self-concept | .935 | 6 |

| Empowerment | .958 | 12 |

| Descriptive | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical | Standard error | |||

|

Standard score total scale |

Mean | 49.07 | 3.367 | |

| 95% confidence interval for the mean |

Lower limit | 42.16 | ||

| Upper limit | 55.98 | |||

| Mean cut to 5% | 48.77 | |||

| Median | 49.50 | |||

| Variance | 317.402 | |||

| Standard deviation | 17.816 | |||

| Minimum | 23 | |||

| Maximum | 82 | |||

| Range | 59 | |||

| Direct score autonomy subscale |

Direct score Self-initiation subscale |

Direct score self-direction subscale |

Direct score self-regulation subscale |

Direct score self-concept subscale |

Direct score empowerment subscale |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Valid | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| Lost | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean | 17.18 | 14.75 | 17.82 | 5.00 | 13.54 | 24.36 |

| Median | 18.50 | 15.00 | 12.00 | 5.00 | 13.50 | 23.50 |

| Modal | 20* | 15 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 12* |

| Standard dev. | 6.360 | 5.434 | 7.444 | 2.055 | 5.594 | 10.275 |

| Variance | 40.448 | 29.528 | 55.411 | 4.222 | 31.295 | 105.571 |

| Minimum | 7 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

| Maximum | 28 | 24 | 35 | 10 | 24 | 46 |

| Autonomy subscale coefficient | Self-initiation subscale coefficient | Self-direction subscale coefficient | Self-regulation subscale coefficient |

Self-concept subscale coefficient |

Empowerment subscale coefficient |

|

| N Valid | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| Lost | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean | .61 | .61 | .37 | .42 | .56 | .51 |

| Median | .66 | .63 | .25 | .42 | .56 | .51 |

| Modal | .71 | .63 | .25 | .25 | .25 | .25 |

| Standard dev. | .23 | .23 | .16 | .17 | .23 | .21 |

| Minimum | .25 | .25 | .25 | .25 | .25 | .25 |

| Maximum | 1.00 | 1.00 | .73 | .83 | 1.00 | .96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).