4.1. Anthropogenic Activities in the Navotas River

A survey questionnaire was administered along with consent interviews to 782 respondents. The results indicated that most respondents were male, comprising 78.6% of the population, while female respondents made up 21.4%. Among the respondents, 71.4% were high school graduates. The marital status was evenly split, with 50% being single and 50% married. The age distribution was as follows: 14.3% were aged 18-27, 21.4% were aged 28-37, 50% were aged 38-47, and 14.3% were aged 48 and above. Respondents belonged to families with 2-4 members (42.9%), 5-7 members (50%), and 8-10 members (7.1%). In terms of occupation, the respondents included fish net weavers (11.51%), fishermen (78.6%), sari-sari store owners (6.39%), and vendors (3.45%).

Table 1 below presents the survey results of anthropogenic activities in the Navotas River.

Table 1 illustrates the anthropogenic activities occurring in the Navotas River. It shows that fishing and boating were common activities in the river. However, respondents claimed that due to the poor water quality at the time, their fish catch had decreased significantly. The survey indicated that activities such as washing clothes, discharging wastewater from laundry, and disposing of untreated household wastewater occurred infrequently. In contrast, activities like irrigating plants with river water, excreting domestic waste, throwing garbage into the river, and practicing aquaculture were never practiced in the river. Respondents mentioned that they used to practice aquaculture, but urban development of industries and commercial sectors led to the purchase of a large area of the river, halting their ability to farm fish and shrimp.

Additionally, they reported having a dumping site located in Barangay Tanza, with garbage collected weekly by waste collectors. However, although the mean score for throwing garbage into the Navotas River is low (x̄ = 1.07) based on the observations during the survey, most of the visible waste in the river was non-biodegradable. This included PET bottles, single-use plastics, plastic food wrappers, Styrofoam, and medical wastes, which are harmful to various species inhabiting the river. These wastes and floating debris came from upstream sources, including the Taliptip River, Sta. Maria River, and Meycauayan River, flowing through the Tanza River (Malabon, Navotas Spared Due to Flood Mitigation Measures: Ang, 2020). Furthermore, these rivers transport waste from commercial establishments, manufacturing industries, households, hospitals, and other facilities that find their way into the Navotas River before it flows out to the Manila Bay.

Based on the interviews, residents admitted having inadequate sanitation. They lacked proper pipelines, such as sewers, drainage pipes, and wastewater pipes. In some cases, the wastewater from their households was directly discharged into the river, as reported by 71.40% of the respondents. Furthermore, during the survey at Navotas River, researchers observed various pollutants. The water had a distinct color and unpleasant odor, ranging from murky brown to greenish hues. Floating debris, including plastic bottles, bags, and other garbage coming from nearby industries, was abundant and created clusters of waste along the river. Industrial runoff was also observed in the river, characterized by an oil sheen on the surface of the water, particularly near the discharge points. Sewage contamination was visible from raw sewage outlets and the presence of fecal matter in some parts of the river.

These field observations justify that the Navotas River is heavily polluted and heavily impacted by different anthropogenic activities.

4.2. Water Quality of Navotas River during the Four-Month Period

The Navotas River, shaped by the high tides and strong currents from Manila Bay, is an essential aquatic habitat in northern Navotas City, providing breeding grounds for various ichthyofaunal species. However, the aquatic resources in the river, particularly fish, are under severe fishing pressure and suffer from deteriorating water quality.

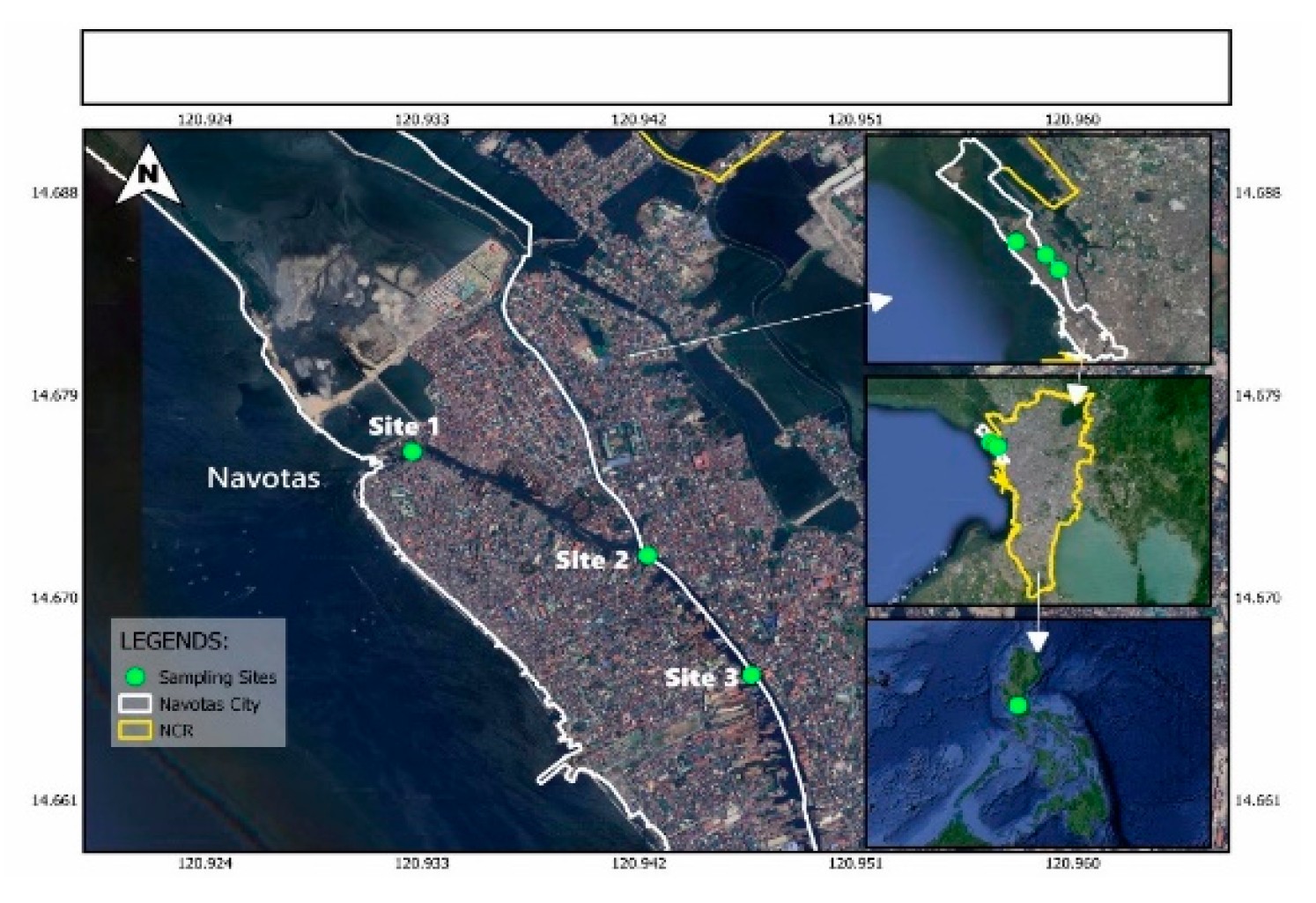

Table 2 presents the physicochemical and microbiological properties of water samples collected from three distinct sites in the Navotas River from January to April 2024. Water quality parameters were compared to the standards set by DENR Administrative Order No. 2016-08 for Class C waters, with fecal coliform and phosphate concentrations compared to the amendment order DENR Administrative Order No. 2021-19.

4.2.1. pH

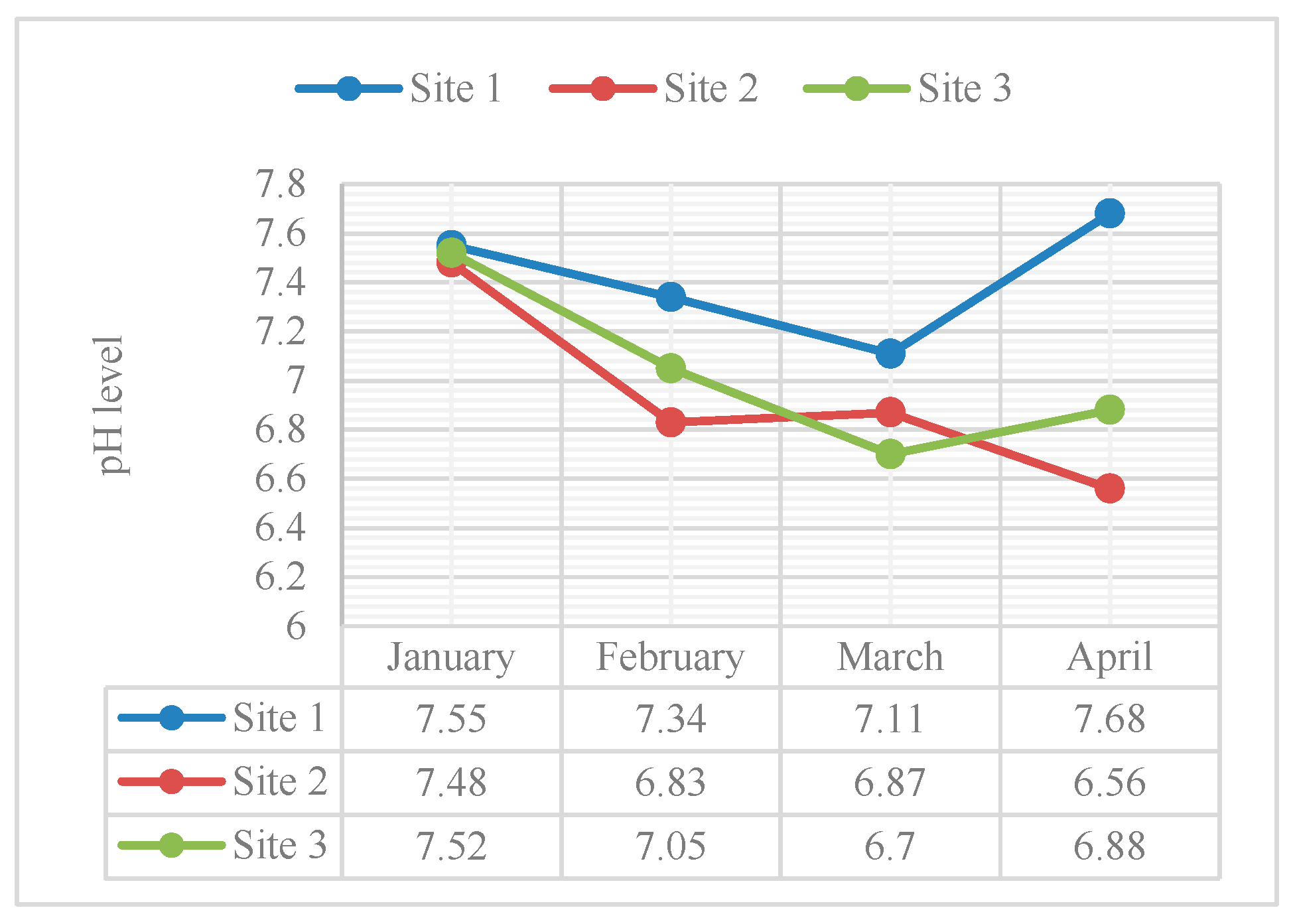

The pH levels of the water in the Navotas River were found to be compliant with the DENR standard value for Class C water at all sites across the four-month sampling period, as measured using a Digital pH Pen Meter.

Figure 3 illustrates the pH levels of the water in three sampling sites during the sampling periods from January to April 2024.

The average pH levels of the water from January to April 2024 were 7.52, 7.07, 6.89, and 7.04, respectively. The pH values acquired from the January, February, and April sampling were slightly basic, while the pH value from the March sampling was slightly acidic. The presence of impurities such as sodium carbonate, potassium bicarbonate, or potassium carbonate influenced the basicity or alkalinity of the water. In contrast, the acidity of the water was attributed to the presence of acidic compounds such as nitrogen compounds. Additionally, the decomposition of dead fish and plants emitted ammonia and other carbon dioxide, lowering the pH of the water and making it more acidic.

The pH levels recorded among the three sampling sites during monthly water sampling from January to April 2024 showed notable variations. Site 1, located at the estuary of Tangos River, consistently exhibited the highest pH level across all sampling months. In contrast, Site 2 recorded the lowest pH level for January, February, and April, but surprisingly exhibited the second-highest pH level in March. Site 3 showed the second-highest pH levels for January, February, and April, but notably had the lowest pH level in March.

The decline in pH level during March may have been attributed to the increasing heat island effect, which caused an increase in biological activity within the river, such as the growth of algae and bacteria (Vergara & Blanco, 2023). Construction projects near the river could have contributed to the decline in the pH level of the water in Navotas River during March 2024. Moreover, human activities, such as the discharge of heated effluents from industrial processes, could have contributed to thermal pollution in rivers. The elevated water temperatures from thermal pollution can directly influence pH levels by affecting chemical equilibria and biological processes.

4.2.2. Temperature

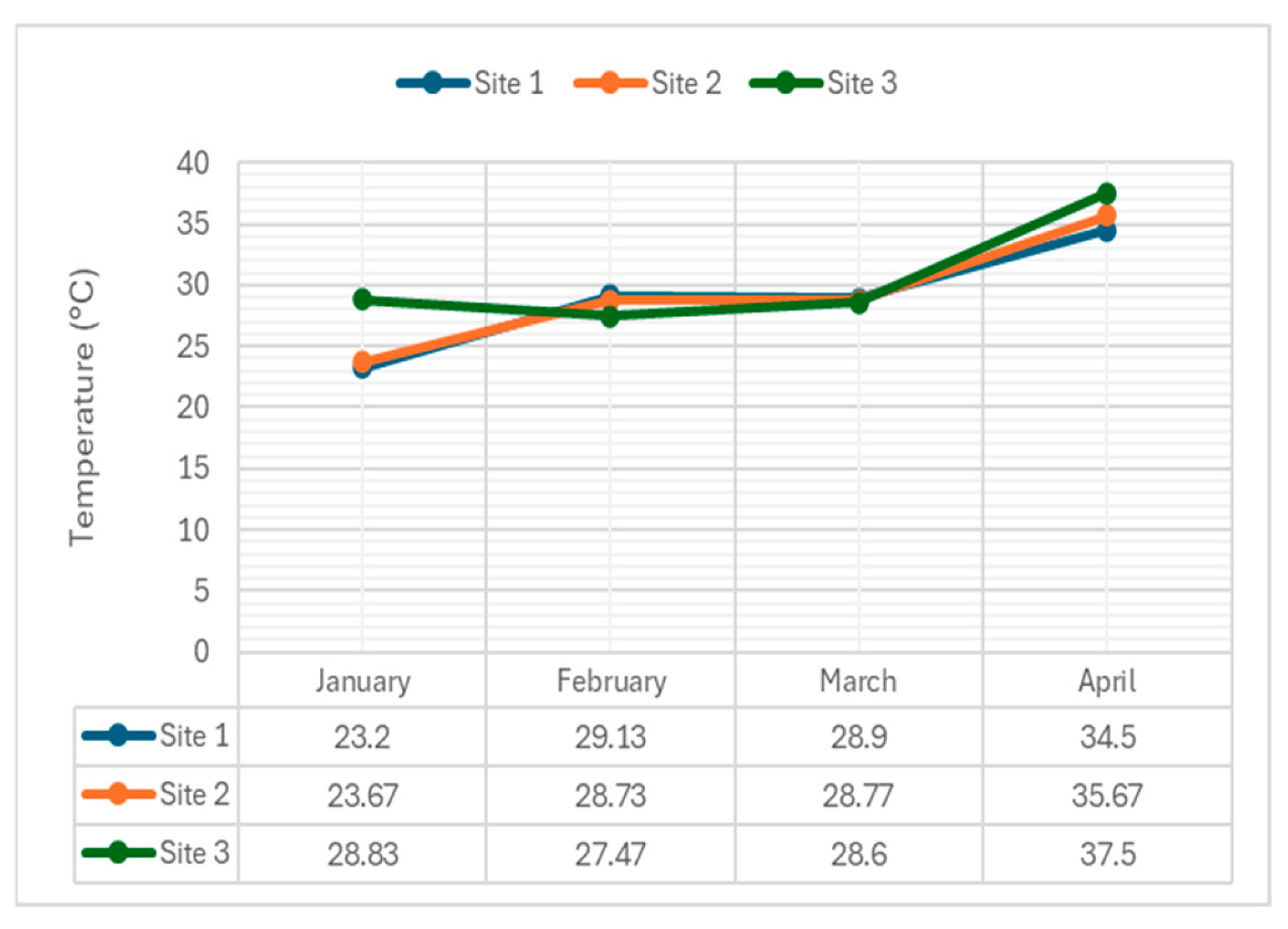

Water temperature plays a crucial role in influencing various physical and chemical properties.

Figure 4 depicts temperature variations at three sampling sites over the four-month period.

The average temperature of the water from January to April 2024 were 25.23 °C, 28.44 °C, 28.76 °C, 35.89 °C respectively. Given the data presented above, it can be clearly seen that the values exceed even the highest limit for Class C water according to DENR DAO 2016-08 particularly in the month of April. All sampling sites exhibited high temperature in April.

4.2.3. Total Dissolved Solids

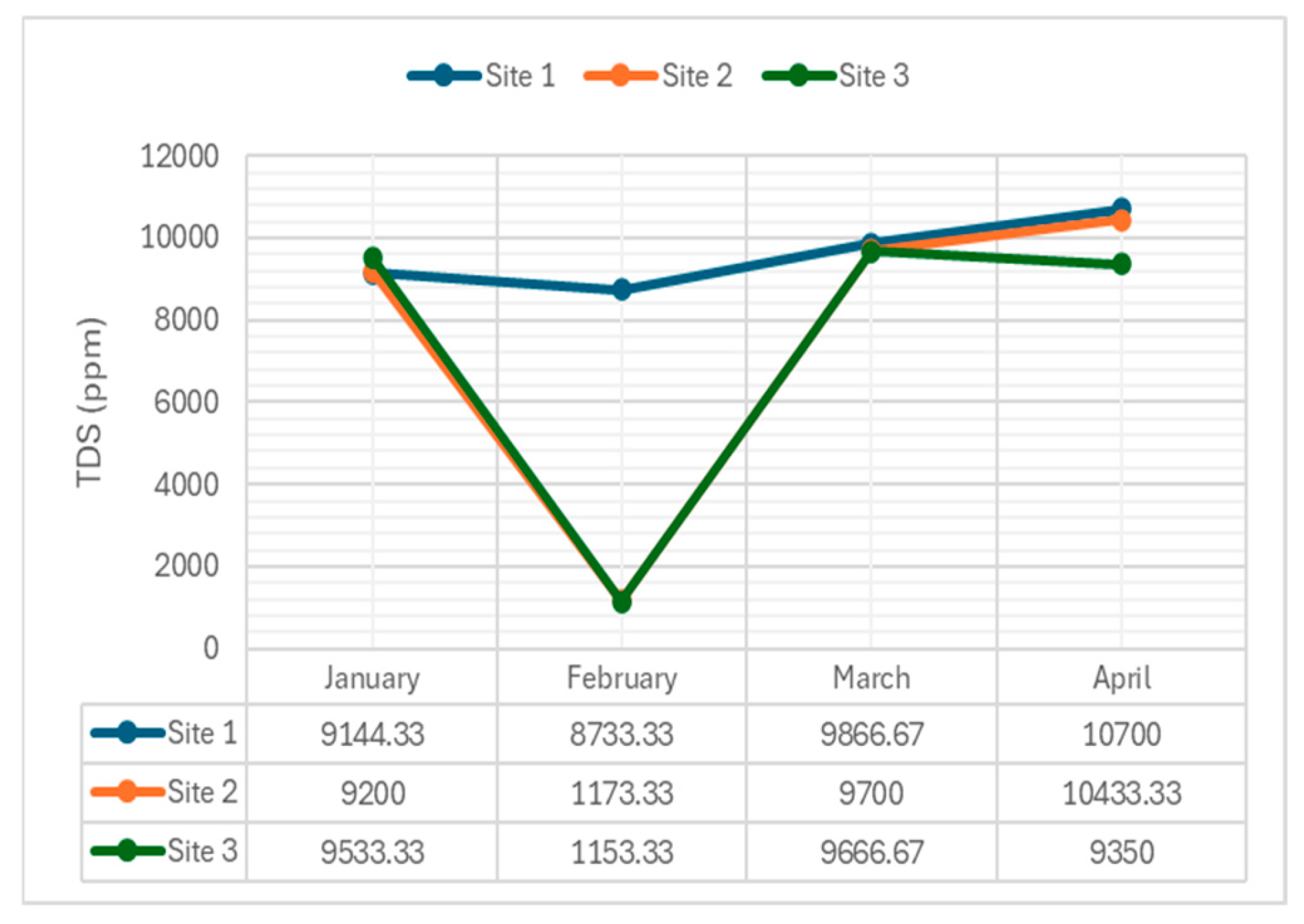

TDS levels, indicative of dissolved mineral content, were measured across the river.

Figure 5 illustrates TDS variations during the sampling period.

The average TDS concentrations recorded during sampling periods were 9611.08 mg/L (Site 1), 7626.67 mg/L (Site 2), and 7425.83 mg/L (Site 3). The results indicated that Site 1 had the highest mean TDS value of 9611.08 mg/L, suggesting significant sources of dissolved minerals and salts at this site. Site 2, with an average of 7626.67 mg/L, had a moderate level of dissolved solids. Site 3 recorded the lowest TDS concentration at 7425.83 mg/L, suggesting less anthropogenic influence in the area.

The consistently high TDS concentrations at Site 1 indicate possible pollution sources affecting the water quality in the Navotas River. Both excessively high and low concentrations of TDS can inhibit the growth and potentially lead to the death of many aquatic organisms. Elevated TDS levels can reduce water clarity and raise water temperatures, impacting the overall health of the aquatic ecosystem.

4.2.4. Electrical Conductivity

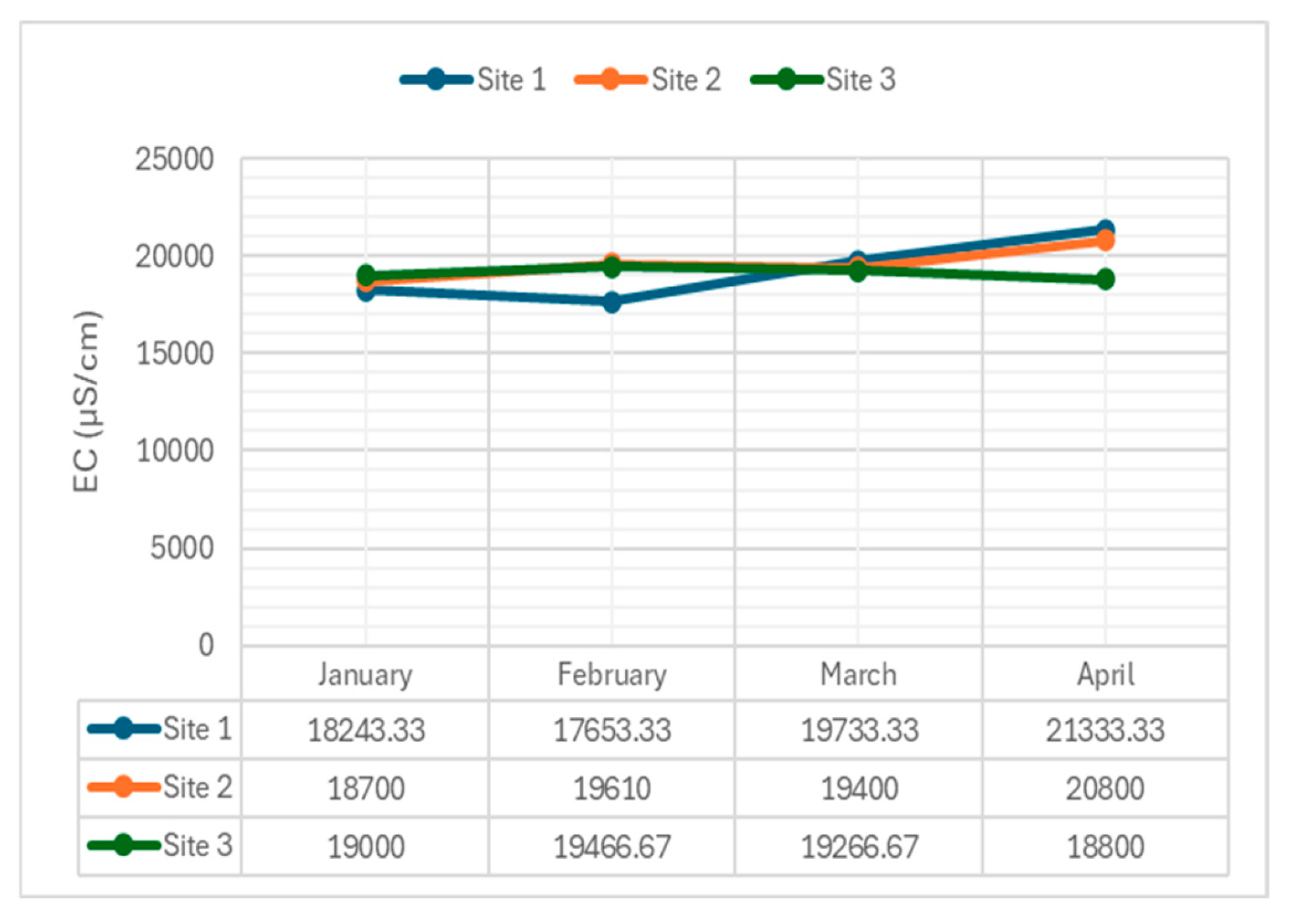

EC measurements reflect water's ability to conduct electricity, influenced by dissolved ions.

Figure 6 presents EC levels across the sampling sites.

The average conductivity of the water from January to April 2024 were 18647.78 µS/cm, 18910.00 µS/cm, 19466.67 µS/cm, and 20311.11 µS/cm respectively. For Site 1, the electrical conductivity (EC) levels exhibited a moderate decrease in February, followed by a constant increase in March and April. This trend indicates an increased concentration of dissolved ions in the water over time. At Site 2, there was a subtle increase in EC levels from January to February, a moderate decrease in March, and an increase in April. This pattern suggests that ion concentrations are generally rising. At Site 3, EC levels were substantial with minor changes, peaking in February and moderately decreasing towards April, indicating that ion concentration is relatively stable with minor fluctuations.

The increased EC levels at Site 1, particularly in April, suggest an inflow of dissolved ions, likely due to increased runoff. This implies that water quality at this site is unfavorable concerning salinity.

4.2.5. Turbidity

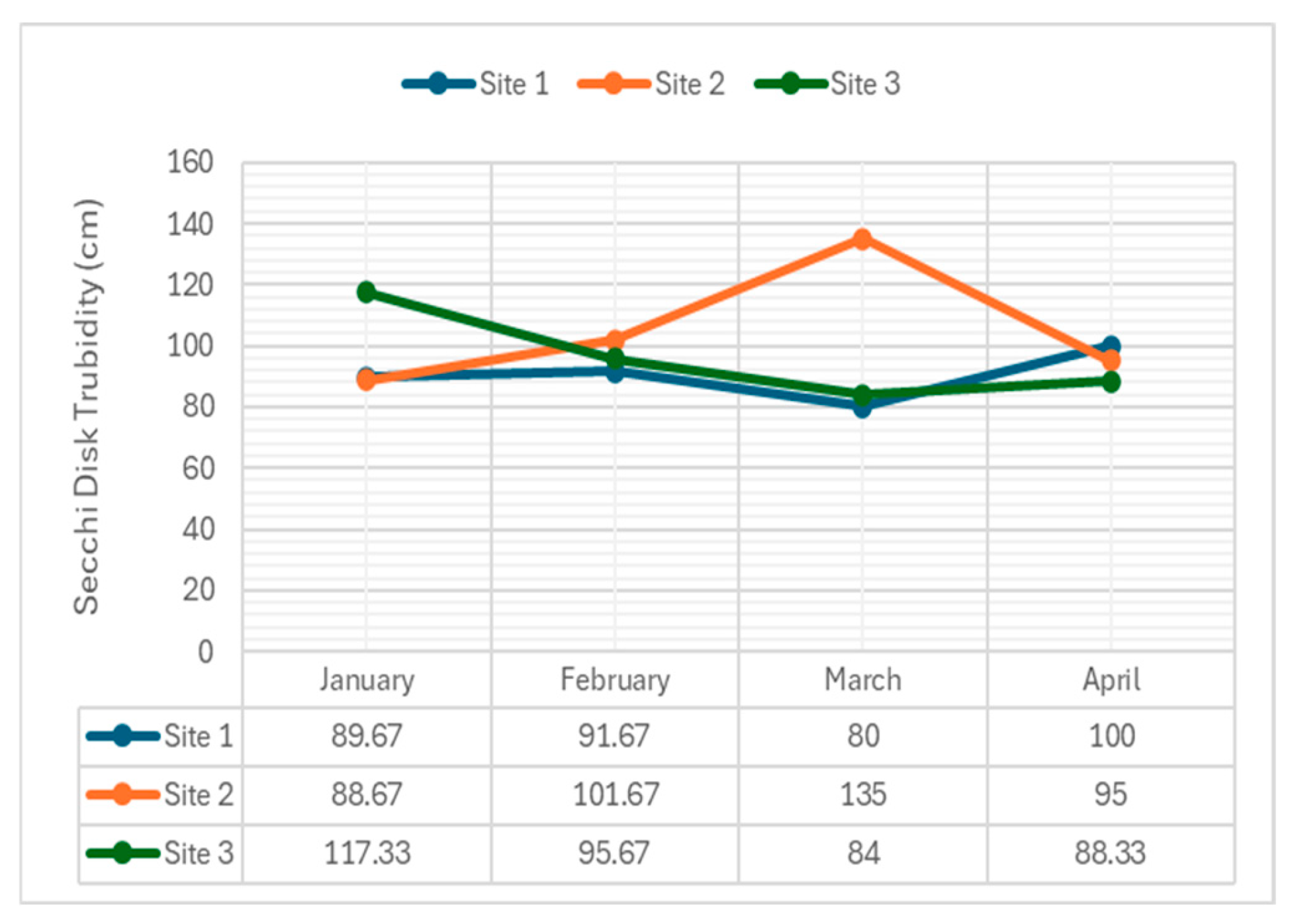

Turbidity, caused by suspended particles, affects water clarity and light penetration.

Figure 7 displays turbidity levels recorded during the study period.

The observed data from Navotas River at three sampling sites over four months presented interesting variations. In January, the values were 89.67 cm at Site 1, 88.67 cm at Site 2, and the highest at 117.33 cm at Site 3, indicating better conditions or higher fish activity at Site 3 compared to Sites 1 and 2. In February, Site 2 recorded the highest value at 101.67 cm, suggesting peak conditions at this site, with Site 1 and Site 3 showing slightly lower values at 91.67 cm and 95.67 cm, respectively. March showed a significant peak at Site 2 with 135 cm, while Sites 1 and 3 had lower values of 80 cm and 84 cm, respectively, indicating a possible seasonal effect or specific event contributing to the high activity at Site 2. In April, Site 1 had the highest observed value at 100 cm, followed by Site 2 at 95 cm and Site 3 at 88.33 cm, suggesting a shift in favorable conditions towards Site 1.

The average observed values per site across all months were 90.34 cm for Site 1, 105.34 cm for Site 2, 96.83 cm for Site 3. This indicates that Site 2 generally had the highest observed values, followed by Site 3 and Site 1. On a monthly basis, the average observed values were 98.56 cm in January, 96.33 cm in February, 99.67 cm in March, and 94.44 cm for April. These averages show relatively consistent levels of activity or conditions throughout the months, with March having the highest average and April the lowest.

4.2.6. Dissolved Oxygen

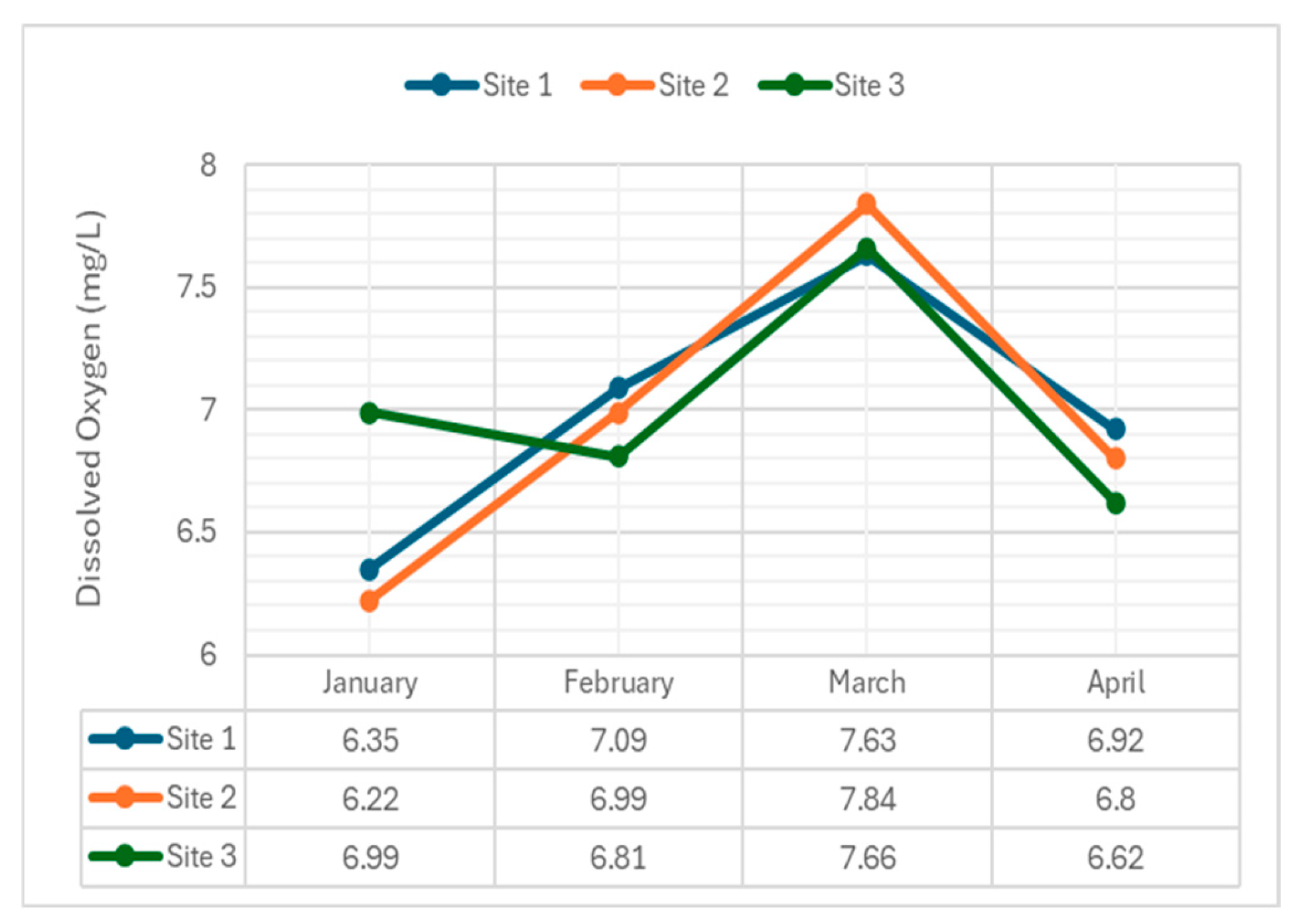

DO levels, crucial for aquatic life, were monitored throughout the river.

Figure 8 illustrates DO variations across the sampling sites.

The concentration of dissolved oxygen (DO) in the Navotas River was measured using the digital DO Meter. The concentration of DO in the river ranged from 6.22 to 7.84 mg/L. The average DO level of water recorded from January to April were 6.52 mg/L, 6.96 mg/L, 7.71 mg/L, and 6.78 mg/L respectively. The DO level in March did not meet the acceptable standards set by the DENR for Class C waters. This can be attributed to the high level of organic waste in the river due to the improper sewage system in the area. Organic materials found in sewage from homes and industries are broken down by microbes, which need oxygen in the process. The variation of DO concentrations among sampling months can be attributed to the changing weather conditions, salinity, total coliform, and other factors.

4.2.7. Nitrates

Nitrates, essential nutrients but indicators of pollution, were measured.

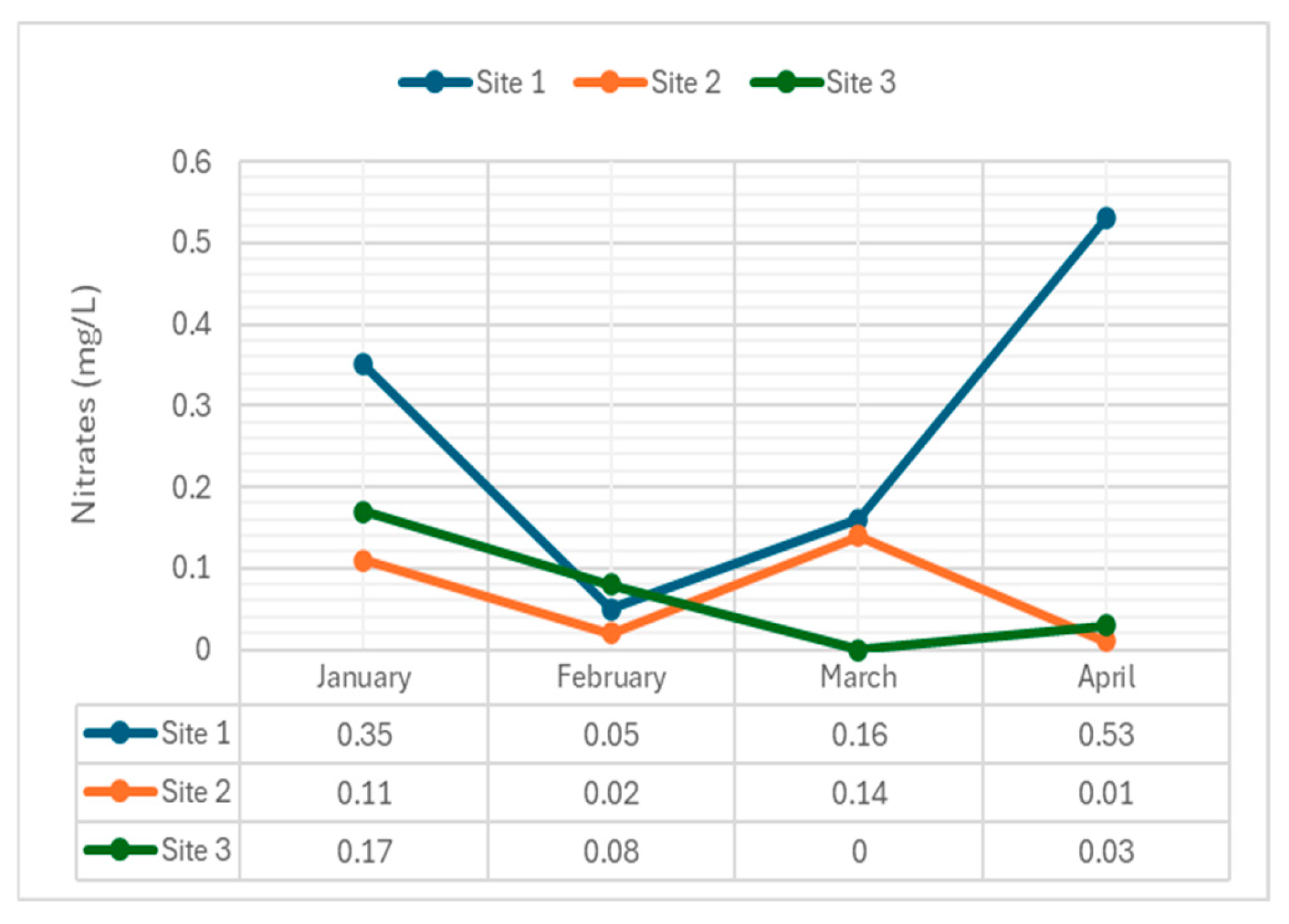

Figure 9 shows nitrate concentrations across the sites.

The average nitrate levels for each site were 0.27 mg/L (Site 1), 0.28 mg/L (Site 2), 0.28 mg/L (Site 3) respectively. These concentrations were within the standard set by DENR for Class C waters. For Site 1, January and April had the highest level of nitrates among all the months and sites. Site 2 and 3 both showed generally lower nitrate concentrations with the lowest result in the month of April. Site 1 consistently showed higher concentrations compared to site 2 and 3. This suggests that the surveyed areas of the Navotas Riverine Ecosystem are affected by anthropogenic activities which can be the cause of presence of nitrates in each of the sites. While the nitrate concentration is typically low in Navotas River, it can possibly become elevated due to industrial waste, refuse dump runoff, or human and animal waste contamination.

4.2.8. Phosphates

Phosphate concentrations, indicative of nutrient pollution, were assessed.

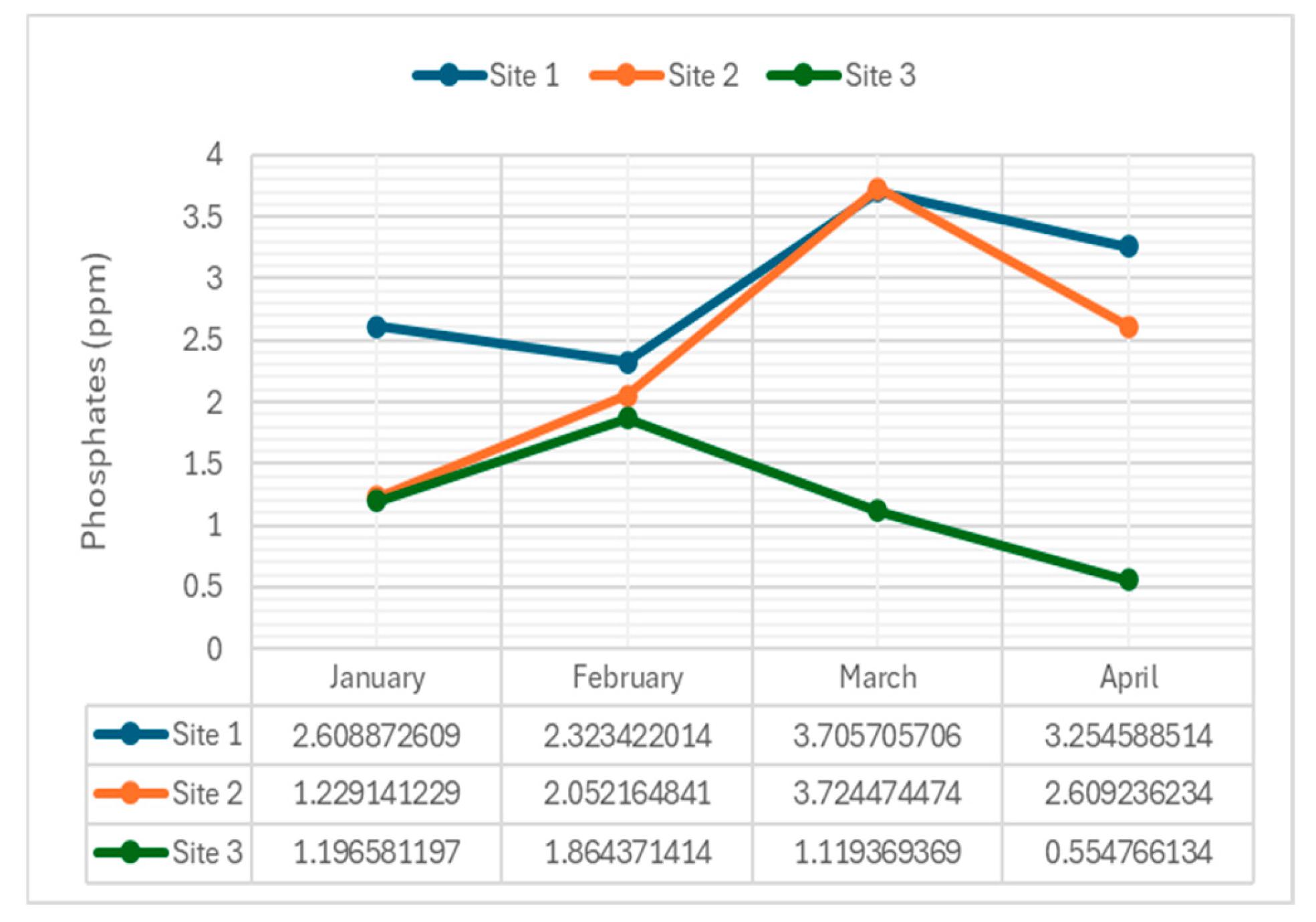

Figure 10 presents phosphate levels across the river.

The phosphate concentration observed from three sites along Navotas River reveals varying levels across different months. Site 1 consistently exhibited higher phosphate concentrations compared to Sites 2 and 3, with average values of 2.47 ppm, 2.16 ppm, and 1.74 ppm, respectively.

The elevated levels at Site 1, averaging 2.47 ppm, suggest significant anthropogenic influences, potentially due to industrial discharge, agricultural runoff, or domestic sewage inputs into the river. Site 2, with an average phosphate concentration of 2.41 ppm, displays fluctuating levels, possibly influenced by seasonal changes, weather patterns, and upstream activities such as heavy runoff or agricultural practices. Conversely, Site 3 consistently showed the lowest phosphate levels, with an average of 1.18 ppm, indicating either minimal upstream phosphate sources or effective natural or man-made processes mitigating inputs. Despite these variations, all sites underscore the importance of effective management strategies to control phosphate pollution and preserve the health of Navotas River's aquatic ecosystem, as even low levels of phosphates can contribute to eutrophication over time when combined with other nutrients like nitrogen.

Phosphates in the Navotas River originate from natural sources, including the release of phosphorus from bed sediments and the breakdown of organic phosphorus compounds by bacteria. These organic compounds are primarily generated by biological systems and are present in debris such as plant waste. Additionally, anthropogenic activities contribute to phosphate levels in the river, with organic phosphates from household food, body waste, and natural animal manure entering the water supply through sewage and wastewater systems. Common household detergents have emerged as a modern source of phosphorus in aquatic bodies, entering wastewater systems and ultimately releasing into surface waters, resulting in elevated phosphate levels.

4.2.9. Fecal Coliform

Fecal coliform levels, indicating contamination from human and animal waste, were monitored.

Figure 11 illustrates fecal coliform concentrations across sampling sites.

At Site 1, a notable increase was observed from January to February, reaching a peak of 160,000 MPN/100mL. Subsequently, in March, a decrease was noted, followed by a further decrease in April. Conversely, at Site 2, a persistent increase was seen from January to March, reaching 160,000 MPN/100mL in March. However, April showed a sudden decrease, albeit remaining at a high level, indicating continuous contamination. The sudden decrease in fecal coliform level in the Site 1 from March to April 2024 may be attributed by the increased temperature in April (34.5 °C) leading to the natural die-off coliform bacteria over time due to increased UV radiation. Site 3 exhibited a consistently high level from January to February and April, with a slight decrease in March, suggesting extreme contamination in this area.

The significant differences in terms of fecal coliform levels in the sampling months (temporal variations) across all sites may be attributed by the seasonal changes during the dry season, particularly on January and February, when the river experience low tide resulting in higher concentration of contaminants due to reduced dilution (X ̅February = 137333.33 MPN/100 mL and X ̅January = 95666.67 MPN/100 mL).

The significant differences in fecal coliform levels among the sampling sites (spatial variations) across the sampling months may be attributed by the site-specific variations whereas sites near the urban areas or industrial zones (Site 2 and Site 3) have consistently higher fecal coliform levels (X ̅Site 2 = 94750 MPN/100 mL X ̅Site 3 = 143000 MPN/100 mL). Overall, all three sites of Navotas River show contamination based on their fecal coliform levels. The frequent occurrence of high levels, particularly reaching 160,000 MPN/100mL, exceeds acceptable thresholds, posing potential health risks to locals exposed to it.

4.6. Ichthyofaunal Diversity of Navotas River

The present study identified fish species in Navotas River belonging to the class Actinopterygii and five families: Scatophagidae, Dorosomatidae, Terapontidae, Lutjanidae, and Cichlidae. The distribution of ichthyofauna in three sites during the sampling periods from January to April 2024 is shown in

Table 6.

A total of 269 fish were collected and identified. The species with the highest total occurrence was Scatophagus argus (18.59%), followed by Pelates quadrilineatus (18.22%).

Scatophagus argus (Linnaeus 1766), belonging to the family Scatophagidae, was the most abundant species. Known as spotted scat, it inhabits brackish estuaries and lower reaches of freshwater streams, frequently occurring among mangroves (Froese & Pauly, 2017; Randall, 2019). Scatophagus argus exhibits a wide salinity tolerance range and can survive in conditions ranging from freshwater to highly saline environments. It can tolerate elevated temperatures and low dissolved oxygen concentrations (Gupta, 2016).

Pelates quadrilineatus (Bloch 1790), locally known as babanse, was the second most abundant species (18.22%). Found in brackish waters, this species often inhabits estuaries, seagrass beds, and mangrove bays, feeding on small fishes and invertebrates (Ching, 2023).

Other species with lower abundances included Sarotherodon melanotheron (gloria tilapia) (17.10%), Terapon jarbua (bagaong) (15.61%), Lutjanus argentimaculatus (alakaak) (12.64%), Lutjanus argentimaculatus (kabang) (9.67%), and Nematalosa nasus (kabase) (8.18%). These species are commonly found in brackish waters, but their lower abundance may be due to seasonal variations, spawning environment differences, and tolerance for water quality changes.

Sarotherodon melanotheron, an introduced invasive species, had the third-highest total occurrence. Its abundance can negatively impact native species by preying on their eggs and juveniles, contributing to the decline of native fish populations (Oluwale & Ugwumba, 2022).

The ichthyofaunal diversity of Navotas River reflects the varying ecological conditions and impacts of anthropogenic activities on the aquatic ecosystem. The presence of both native and invasive species indicates the complexity of biotic interactions and the influence of environmental factors on fish communities. The study highlights the importance of continuous monitoring and management to preserve the ecological balance and biodiversity of Navotas River.

4.6.1. Species Importance Value

The Species Importance Value (SIV) index measures species dominance within a specific area, determined as the sum of relative frequency, relative dominance, and relative density (Ismail et al., 2017).

Table 7 shows the Species Importance Value of ichthyofaunal species, highlighting the most and least important species in the Navotas River.

Scatophagus argus (kitang) holds the highest importance value (53.84), followed by Pelates quadrilineatus (babanse) with an importance value of 51.02. The invasive Sarotherodon melanotheron has the third-highest importance value (50.87). Conversely, Nematalosa nasus (kabase) has the lowest importance value (26.76).

The abundance of S. argus indicates its dominance in the river, attributed to its resilience to environmental stressors like water pollution. Its omnivorous diet allows it to adapt to a degraded environment, feeding on detritus, algae, small invertebrates, and plant matter. Additionally, S. argus has a high reproductive rate and reaches maturity quickly, maintaining its population regardless of conditions.

Conversely, N. nasus, with the lowest importance value, demonstrates a preference for conditions less suitable to the polluted environment of the river, such as lower DO and high pollutant levels, which are disadvantageous compared to species like S. argus.

The distribution of fish species in the Navotas River provides insights into the river's health and species diversity. Identifying the pattern of species richness and the distribution of dominant species, such as

S. argus, serves as an effective biomarker of the river’s condition and the impact of pollution on fish. Analyzing these patterns highlights how environmental stressors influence biodiversity and sustainability of aquatic life in the Navotas River.

Table 8 shows the biodiversity status of collected fish species in Navotas River.

Among the collected species, only Pelates quadrilineatus is listed as "Not Evaluated," while the remaining six species are categorized as "Least Concern." Six species are native, while Sarotherodon melanotheron (Gloria Tilapia) is introduced.

4.6.2. Species Diversity of Ichthyofauna in Navotas River

Biodiversity indices, including the Shannon-Wiener Index, Simpson’s Diversity Index, and Margalef’s Richness Index, were used to assess the diversity and similarity of ichthyofaunal species in the Navotas River system. Presented in

Table 9 were the values obtained from computed species diversity indices.

The Shannon-Wiener Index revealed that Site 1 had the highest diversity (H’ = 1.91), followed by Site 2 (H’ = 1.87). Site 3 had the lowest diversity (H’ = 1.71). According to the "Classification Scheme of Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index" by Fernando et al. (1998), an index value ≤ 1.99 indicates low species diversity. The Simpson’s Index of Diversity (1-D) indicated that Site 1 and Site 2 had relatively high diversity values (0.85 and 0.86, respectively), compared to Site 3 (0.82). The Reciprocal (1/D) of Simpson’s Diversity Index showed that Site 2 had the highest diversity (1/D = 7.04), followed by Site 1 (1/D = 6.81), and Site 3 (1/D = 5.48). Margalef’s Richness Index revealed that Site 2 had the highest richness (dmg = 1.57), followed by Site 3 (dmg = 1.45), and Site 1 (dmg = 1.18), indicating Site 1 had the lowest species richness.

Overall, Navotas River had low diversity (SDI ≈ 0.99), likely due to anthropogenic activities such as pollution and the proliferation of invasive species like Gloria Tilapia (S. melanotheron), which compete for food sources and prey on smaller organisms.

4.6.3. Species Similarity and Species Evenness in Navotas River

Understanding fish species' biodiversity and distribution in Navotas River is crucial for conservation efforts and monitoring ecosystem health. Sorensen’s Coefficient Similarity Index quantifies the similarity between communities, and Shannon Equitability measures species abundance evenness. Presented in

Table 10 and

Table 11 were the values obtained from computed species similarity and evenness.

Site 1 and Site 3 have the highest similarity (80%), likely due to shared water conditions and environmental features. The 60% similarity between Site 1-Site 2 and Site 2-Site 3 can be attributed to distinct environmental conditions at Site 2, located at the diverting channel of Tangos and Tanza Rivers.

Table 11.

Shannon’s Equitability Index for Sampling Sites during the Four-month Sampling Periods.

Table 11.

Shannon’s Equitability Index for Sampling Sites during the Four-month Sampling Periods.

| Sampling Month |

EH

|

| Site 1 |

Site 2 |

Site 3 |

| January |

0.63 |

0.64 |

0.35 |

| February |

0.91 |

0.76 |

0.75 |

| March |

0.83 |

0.55 |

0.76 |

| April |

0.85 |

0.33 |

0 |

Shannon’s Equitability Index showed that in January, Site 2 had the highest evenness (0.64), followed by Site 1 (0.63). In February, March, and April, Site 1 had the highest evenness (0.91, 0.83, and 0.85, respectively). Site 3 recorded 0 evenness in April, likely due to high water temperatures impacting fish presence and distribution.