1. Introduction

Acrylonitrile-butadiene copolymer (NBR) is a special-purpose rubber whose main advantage is high resistance to chemicals such as oils, fuels and fats. NBR products are also characterized by very good vibration damping properties. Therefore, products made of NBR are components of tires, inner tubes, bumpers, and are used to produce various types of seals and hoses for liquid fuels and oils [

1].

Industrially, NBR is used in combination with various fillers that provide an appropriate mechanical strength. In the literature, there are mainly research works on the use of silica [

2], carbon black [

3], layered minerals, e.g., montmorillonite [

4] or hydrotalcite [

5], as NBR fillers. The application of waste biofillers, e.g. keratin [

6] or eggshells [

7], as potential fillers of this elastomer has also been tested. However, these studies often did not consider the impact of the fillers used on flammability and resistance of NBR vulcanizates to aging or chemicals. Moreover, silica usually resulted in an increase in the stiffness of the material and a significant reduction in elasticity, carbon black determined the black color of the vulcanizates, whereas in the case of layered minerals, it was necessary to use special methods of preparing rubber compounds, e.g. in situ polymerization or solvent intercalation, to obtain composites with an exfoliated structure, characterized by satisfactory performance properties. Therefore, it is still justified to search for new NBR fillers that will not have a negative impact on its main advantage, i.e. oil and fuel resistance, and at the same time will allow obtaining composites with improved properties, e.g. anti-aging resistance or reduced flammability.

Hydroxyapatite (HAP) is a naturally occurring mineral composed of calcium hydroxyphosphate with the chemical formula 3Ca

3(PO

4)

2·Ca(OH)

2. Generally, HAP is the main inorganic component of bones and teeth. It constitutes a mineral scaffold of connective tissue responsible for the mechanical strength of bones. Thus, it plays a crucial role in living organisms. HAP is commercially available either from a natural source or as synthetic powder, hence, in recent years it has found more and more technological applications. Due to its biocompatibility, bioactivity and resistance to degradation, HAP is commonly used in medical applications, such as bone tissue engineering, implants and drug delivery systems [

8]. On the other hand, owing to its high thermal stability, non-toxicity, environmentally friendly nature and commercial availability, HAP can be successfully used in polymers, including elastomer composites [

9,

10].

Regarding elastomer composites, there are some literature reports on the applications of HAP mainly in natural rubber latex [

11], silicone rubber [

12] or carboxylated acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber [

13]. Most of them concerns rubber composites for biomedical applications. Regarding applications of HAP in NBR composites, Nihmath et al. [

14] studied the effect of HAP nanoparticles on the thermal stability and electrical properties of vulcanizates. Incorporation of HAP increased the thermal decomposition temperature and electrical conductivity of the composites. However, the effect of HAP on other functional properties of NBR has not been investigated. Bureewong et al. [

15] examined NBR composites filled with HAP obtained from fish scales. The positive influence of the HAP incorporation on the vulcanization, tensile properties and chemical resistance of NBR was reported. Nevertheless, only the effect of HAP on the toluene resistance of NBR was investigated, not including oils and fuels, which are important for industrial applications of this rubber. Nihmath et al. [

16,

17,

18,

19] performed a series of studies on the use of HAP as a filler for chlorinated NBR and its blends with chlorinated ethylene-propylene-diene terpolymer, which confirmed the positive effect of HAP also on the functional properties of chlorinated rubbers.

In this work, we studied the possibility of using HAP to develop NBR composites with improved cure characteristics, i.e., reduced time and temperature of vulcanization, enhanced functional properties, mainly thermal stability, resistance to thermo-oxidative aging and resistance to oils and fuels. No less important was the reduction of flammability, since NBR is commonly used for rubber products working in contact with flammable liquids. To improve the dispersibility of HAP particles in the polar NBR matrix, dispersants of different characteristics were employed such as silane (APTES), imidazolium ionic liquid (DmiBr) and ammonium surfactant (CTAB), which are commonly used as coupling agents of fillers (silane) or templates for synthesis of HAP particles (DmiBr, CTAB). To our knowledge, such composites have not yet been the subject of research described in the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber (SKN3365E type) was purchased from Konimpex Chemicals (Konin, Poland). It contained of 31–35 wt.% of acrylonitrile and was characterized by the Mooney viscosity of ML1+4 (100°C):62-68. The standard sulfur curing system was used to produce vulcanizates. It contained sulfur (Siarkopol, Tarnobrzeg, Poland) as a curing agent, 2-mercaptobenzothiazole (MBT, Sigma-Aldrich, Poznań, Poland) as a vulcanization accelerator and zinc oxide (ZnO) (Huta Będzin, Będzin, Poland) along with stearic acid (St.A.) (Sigma-Aldrich, Poznań, Poland) as activators. Synthetic hydroxyapatite (HAP), i.e., calcium phosphate hydroxide with a formula of 3Ca3(PO4)2·Ca(OH)2 purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Poznań, Poland), was used as a filler. To improve the dispersibility of HAP particles in the elastomer matrix, and thus their activity, the following dispersants were used: (3-aminopropyl)-triethoxysilane (APTES, Sigma-Aldrich, Poznań, Poland), 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide (DmiBr, IoLiTec, Heilbronn, Germany), and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, Sigma-Aldrich, Poznań, Poland).

2.2. Preparation of NBR Compounds and Vulcanizates Filled with Hydroxyapatite

NBR composites with the general recipes given in

Table 1 were prepared using a laboratory two-roll mill (David Bridge & Co, Rochdale, UK, Country) equipped with rolls of the following dimensions: diameter - 200 mm, length - 450 mm, which worked with the friction of 1.0-1.2 mm, the width of the gap between rollers of 1.5-3.0 mm, and the rotational speed of the front roll of 16 min

-1. The average temperature of the rolls during compounding was approximately 30 °C. During the preparation of each of the NBR composite, the following procedure was used: first, the rubber was masticated for 5 minutes, then the components of the rubber compounds were introduced in the following order: HAP, St.A., ZnO, MBT and sulfur. In the case of rubber composites with dispersants, they were added before the sulfur was introduced. As a result, sheets of rubber compounds approximately 5 mm thick were obtained, which were stored in a refrigerator at 5 °C.

To prepare the plates of vulcanizates with a thickness of approximately 1 mm, the sheets of NBR compounds were vulcanized at 160 °C using hydraulic press with electrical heating. Vulcanization of each rubber compound was carried out using the optimal vulcanization time determined from rheometric measurements.

2.3. Characterization of NBR Compounds and Vulcanizates Filled with Hydroxyapatite

The cure characteristics of NBR composites were recorded at 160 °C according to the ISO 6502 [

20] standard procedures by using a rotorless rheometer D-RPA 3000 (MonTech, Buchen, Germany). The following parameters of rubber compounds were determined: minimum torque during vulcanization (S

min), maximum torque during vulcanization (S

max), optimal vulcanization time (t

90), and scorch time (t

02).

A differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) (DSC1, Mettler Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland) was employed to determine the temperature range and enthalpy of the NBR vulcanization. Measurements were carried out according to procedures described in ISO 11357-1 [

21] standard. NBR compounds with a mass of approximately 20 mg were heated from –100 °C to 250 °C in an argon atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C/min.

The ISO 37 [

22] standard was applied to examine the tensile properties of the vulcanizates. Analysis was performed using a universal testing machine Zwick/Roell 1435 (Ulm, Germany). Five dumb-bell-shaped specimens with a width of the measuring section of 4 mm were studied for each vulcanizate.

The Shore A hardness was measured using Zwick/Roell 3105 (Ulm, Germany) tester. Measurements for disc-shaped specimens of the vulcanizates were carried out according to the standard procedures described in ISO 868 [

23]. The average of 6 determinations was taken as the measurement result for each vulcanizate.

An equilibrium swelling procedure given in ISO 1817 [

24] standard was adopted to determine the crosslink density of the NBR vulcanizates. Measurements were performed for small pieces of vulcanizates with a mass in the range of 30-40 mg, which were swollen in toluene for 48 hours at room temperature. The crosslink density was calculated adopting the Flory-Rehner equation [

25] for the Huggins parameter of NBR-toluene interaction given by Equation (1) [

26], where V

r was the volume fraction of elastomer in swollen gel.

The resistance of NBR vulcanizates to oils and fuels was examined by swelling the vulcanized specimens in gasoline (Orlen, Płock, Poland), engine oil and hydraulic oil (Castrol, Pangbourne, UK) for 24 hours at room temperature. Then, the percentage change in the sample mass caused by the action of a solvent was calculated and expressed as the percentage of the original mass (Q, swelling percent), given by the Equation (2) [

27], where m was the mass after swelling and m

0 was the initial mass of the sample before swelling.

A DMA/SDTA861e analyzer (Mettler Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland) working in a tension mode was employed to study dynamic-mechanical properties of the vulcanizates. During measurements of the dynamic moduli, samples of the vulcanizates were heated from -100 °C to 70 °C with a heating rate of 3 °C/min. Analysis was performed using a frequency of 1 Hz, and a strain amplitude of 4 µm.

The resistance of NBR vulcanizates to thermo-oxidative aging was examined following the ISO 188 standard [

28]. To perform the aging process, plates of vulcanizates were stored in a drying chamber (Binder, Tuttlingen, Germany) at 100 °C for 7 days (168 hours). The aging coefficient (

Af), which quantifies the resistance of elastomer to prolonged thermo-oxidation, was calculated according to Equation (3) [

29], where TS was the tensile strength, and EB was the elongation at break of vulcanizates.

A TGA/DSC1 (Mettler Toledo) thermogravimeter was employed to investigate the thermal stability of NBR composites. Two-step procedure was adopted to perform TG measurements. First, small pieces of vulcanizates with a mass of approximately 10 mg were heated from 25 °C to 600 °C in an argon atmosphere (gas flow 50 ml/min) at a heating rate of 20 °C/min. Next, gas was changed into air (gas flow 50 ml/min) and heating was continued up to 800 °C with the same heating rate.

The flammability of NBR composites was examined by employing a cone calorimeter (Fire Testing Technology Ltd., East Grinstead, UK). Measurements were carried out for squared specimens of vulcanizates with dimensions of 100 × 100 × 2 mm. During the analysis samples were irradiated horizontally using a 35 kW/m2 heat flux density.

A scanning electron microscope LEO 1450 (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) was adopted to establish the degree of dispersion of HAP particles and other ingredients in the NBR elastomer matrix. SEM images were taken for vulcanizate fractures in liquid nitrogen. Prior to the measurements, fractures of the vulcanizates were covered with a thick layer of carbon.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Influence of Dispersants on the Hydroxyapatite Dispersibility in the NBR Composites

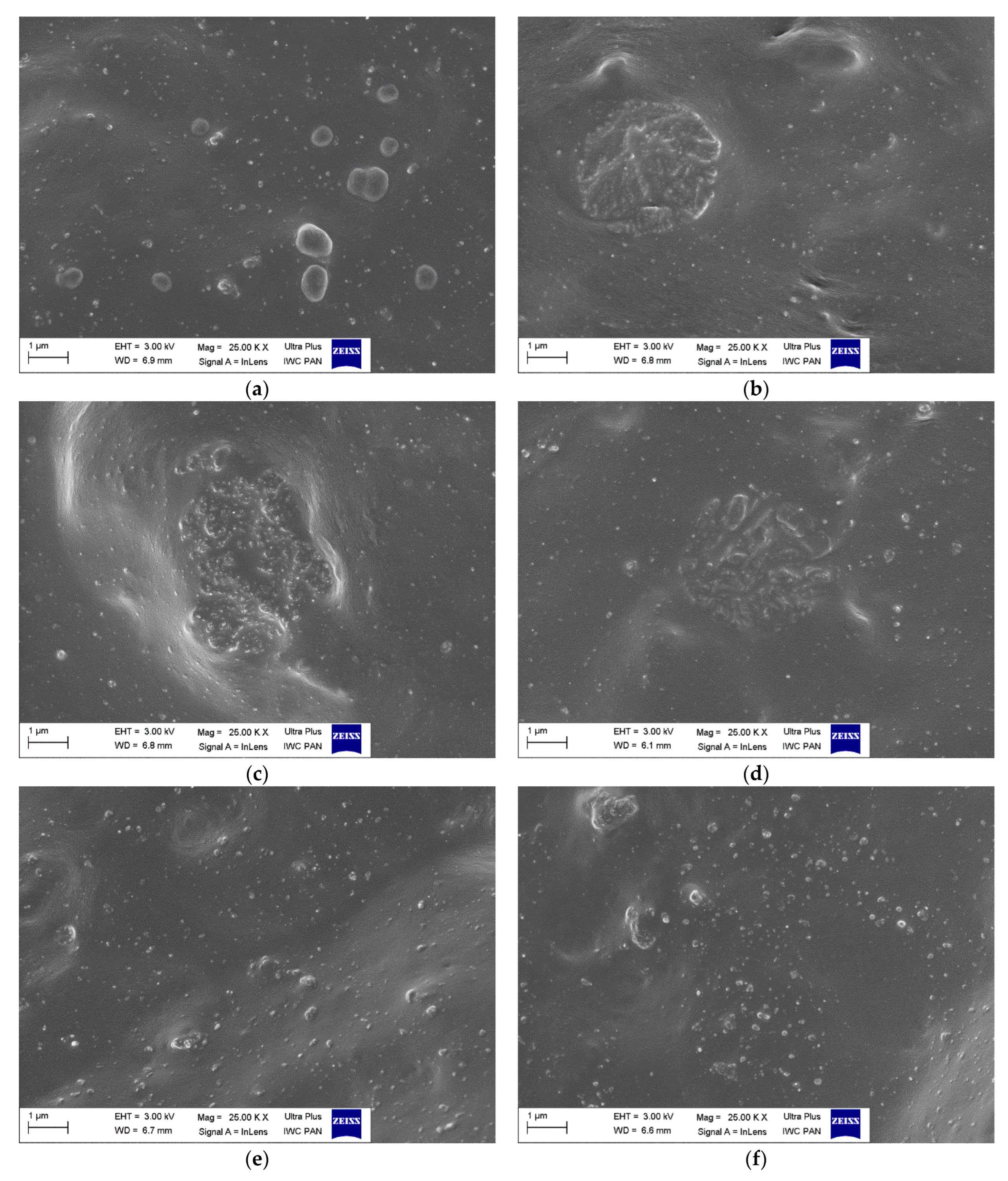

In the first step of the research, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to examine the dispersion degree of HAP particles in the NBR elastomer matrix. Furthermore, the influence of dispersants, i.e., silane APTES, ionic liquid DmiBr and surfactant CTAB, on the HAP dispersibility in the NBR composites was established. SEM images of vulcanizate fractures are presented in

Figure 1.

Regarding the unfilled NBR vulcanizate, single agglomerates were observed heterogeneously distributed in the elastomer matrix (

Figure 1a). The size of these agglomerates was approximately 1 micrometer. Since this vulcanizate contained only a crosslinking system composed of sulfur, accelerator, zinc oxide and stearic acid, it can be concluded that the agglomerates visible in the SEM image were created by the components of the crosslinking system, or a by-product of their reaction, which may be zinc sulfide [

30].

Analysis of SEM images of vulcanizates filled with HAP (

Figure 1b and 1c) revealed the tendency of HAP particles to agglomerate in the NBR matrix. SEM images showed agglomerates with a size of 3-5 micrometers, and the size of the agglomerates increased with the HAP content in the composite. These agglomerates were well wetted with the elastomer and thoroughly covered with the elastomer film.

The use of APTES silane as a dispersant did not have a significant impact on the degree of dispersion of HAP particles in the NBR elastomer matrix (

Figure 1d). Agglomerates were still observed in the SEM image, although their size was slightly smaller than the agglomerates present in the SEM image of the 30HAP vulcanizate, which did not contain silane. The most effective dispersant was the ionic liquid DmiBr, which ensured uniform dispersion of all components of the NBR composite (

Figure 1e). It should be mentioned that imidazolium ionic liquids are often used as templates in the synthesis of HAP to control the growth and morphology of HAP particles [

31,

32,

33]. Due to their ionic structure, ILs can interact with HAP both through ionic interactions and π-π stacking interactions. This way ILs can cover the HAP surface to improve the morphology and crystallinity during synthesis [

31]. Similar interactions between HAP and the ionic liquid in the elastomeric matrix can prevent the agglomeration of HAP particles in the elastomer composites. The CTAB surfactant also showed satisfactory effectiveness as a dispersant, and generally a uniform dispersion of HAP was observed in SEM image of the vulcanizate with CTAB. Single agglomerates were also present, but their size did not exceed 1 micrometer, so it was much smaller than in the case of the 30HAP vulcanizate. CTAB is one of the most popular surfactants used as a template for the synthesis of HAP particles with defined morphology. By creating micelles, it surrounds the growing particles and prevents their aggregation during the synthesis process [

34,

35,

36]. It may also have a similar effect in an elastomer matrix.

3.2. The Influence of Hydroxyapatite and Dispersants on the Cure Characteristics of NBR Composites

In the next step of the study, the influence of the HAP loading on the cure characteristics of NBR composites was studied with respect to the unfilled rubber compound. Next, the effect of dispersants was discussed in relation to the NBR composite filled with 30 phr of HAP. The results of rheometric measurements and crosslink densities of NBR composites cured at 160 °C are presented in

Table 2.

The minimum torque (S

min) is an important parameter from a processing point of view, as it relates to the viscosity of the uncured rubber compound [

37]. It is assumed that the greater the S

min, the greater the viscosity of the uncured rubber compound, and therefore its processing is somewhat more difficult. HAP and silane had no significant effect on the S

min, whereas incorporation of ionic liquid DmiBr and surfactant CTAB resulted in a significant increase in the S

min, and thus in the viscosity of the uncured rubber compound as compared to the unfilled NBR.

Applying HAP enhanced the maximum torque (Smax) compared to the unfilled NBR. Moreover, Smax increased with increasing HAP content in the rubber compound. This is due to the hydrodynamic effect of the filler, which formed a rigid phase in the elastomeric matrix. The addition of dispersants increased the Smax value compared to 30HAP, with silane APTES having the least effect of these additives and DmiBr the greatest.

The torque increment (ΔS) values showed a similar tendency to the S

max. The ΔS increased with the increase in the HAP content, which resulted from the hydrodynamic effect of the filler since HAP did not significantly affect the crosslink density (ν

t) of the vulcanizates. Importantly, silane, ionic liquid and surfactant caused a significant increase in ΔS compared to the rubber compounds without these additives. It was due to the significantly enhanced ν

t of the composites containing these dispersants (

Table 2). Vulcanizates with DmiBr and CTAB exhibited significantly higher crosslink density compared to the unfilled NBR and other vulcanizates filled with HAP. Thus, it could be concluded that CTAB and DmiBr could catalyze the crosslinking reactions. On the other hand, these additives significantly improved the dispersion of the curatives in NBR elastomer matrix, thus facilitating contact between the curatives and, consequently, improving the efficiency of the crosslinking reaction.

Importantly, the addition of HAP extended the scorch time (t02) of the composites by approximately 1 minute compared to the unfilled sample, which is beneficial for processing safety. The amount of filler and addition of silane had no significant effect on this parameter. On the other hand, ionic liquid and surfactant shortened the scorch time to 0.4 minutes.

The use of HAP significantly extended the optimal time of vulcanization (t

90) compared to the unfilled NBR. The t

90 was extended from 16 minutes for the unfilled NBR to approximately 28 minutes for HAP-filled rubber compounds. According to Nihmath et al. [

16] hydroxyl groups of HAP may promote adsorption of curatives on the HAP surface. This, in turn, may reduce the activity of the curing system, particularly vulcanization accelerators, thereby reducing the rate of the vulcanization. APTES did not have a significant effect on this parameter, because the t

90 of the rubber compound with silane was comparable to the composite without APTES. Both the ionic liquid and the surfactant significantly reduced the optimal vulcanization time, up to 4 minutes for CTAB, and 2 minutes for DmiBr, respectively. Such short t

90 is industrially desirable and beneficial for economic reasons. This confirmed that the addition of ionic liquid and surfactant enhanced the activity of the crosslinking system. It may result from both the previously mentioned improvement in the dispersion of the curatives as well as the interactions of HAP with the surfactant and ionic liquid. Both CTAB and ionic liquids have been commonly used in the HAP synthesis because they can interact with HAP particles controlling their growth and limiting aggregation [

31,

34]. Thus, they can interact with HAP in the elastomeric matrix and block some of the active centers on its surface, and consequently restrict the adsorption of the crosslinking system, including the vulcanization accelerator, on the HAP surface.

The beneficial influence of the ionic liquid and surfactant on the NBR vulcanization was confirmed by DSC results, which are presented in

Table 3.

Applying of HAP increased the onset crosslinking temperature by 14-16 °C compared to the unfilled rubber compound, which could be due to the postulated in the literature adsorption of the curatives on the HAP surface. On the other hand, the amount of heat released during crosslinking increased, i.e., the crosslinking enthalpy, compared to the unfilled benchmark. The applied additives had a positive influence on the crosslinking reactions, since they significantly reduced the onset crosslinking temperature. The most pronounced reduction in the crosslinking temperature was observed for the ionic liquid and surfactant, i.e., DmiBr and CTAB, respectively. Vulcanization of the rubber compounds containing DmiBr and CTAB started at a temperature 30-35 °C lower compared to 30HAP.

Most importantly, using HAP with the ionic liquid and surfactant allowed for a significant increase in the crosslinking efficiency of NBR compounds, as evidenced by a reduction of the vulcanization time and temperature, as well as an increase in the crosslink density of NBR compared to the unfilled composite and those without dispersants.

3.3. The Influence of Hydroxyapatite and Dispersants on the Tensile Properties and Hardness of NBR Composites

The next step of the research was to explore the influence of HAP and applied dispersants on the mechanical properties of NBR vulcanizates. The stress at 300% relative elongation (SE

300), tensile strength (TS), elongation at break (EB) and hardness of the vulcanizates were measured. The results are presented in

Table 4.

The SE

300 parameter correlates with the ν

t of the vulcanizates. Due to the lack of a significant effect on the ν

t, HAP also had no meaningful influence on the SE

300 compared to the unfilled vulcanizate. TS of the vulcanizates filled with HAP was comparable to that of the unfilled NBR, since the values of TS were within the standard deviation. HAP also did not significantly affect the EB of the vulcanizates, and therefore their elasticity. Due to the hydrodynamic effect of the filler, vulcanizates filled with HAP exhibited by approximately 4-6 Shore A higher hardness as compared to the unfilled benchmark. The influence of the dispersing agents on the tensile properties of the vulcanizates correlated with their effect on the ν

t. Vulcanizate with APTES showed higher ν

t compared to 30HAP, and thus slightly higher SE

300, lower EB and higher hardness. It should be noticed that applying APTES improved the TS compared to 30HAP vulcanizate. This could result from both an improvement in the dispersion of the vulcanizate components, including HAP, and an increase in the crosslink density compared to 30HAP. On the other hand, due to the higher ν

t, vulcanizates containing DmiBr or CTAB were characterized by significantly higher SE

300 and hardness compared to 30HAP. On the other hand, increasing the ν

t of these vulcanizates did not result in an improvement in TS, and additionally, a significant reduction in EB (by approximately 400%) was observed compared to 30HAP, which indicated that these vulcanizates were over-crosslinked. It is commonly known that TS increases with ν

t to some critical value of the ν

t. Further increase in ν

t causes TS to deteriorate because the vulcanizate becomes brittle and breaks quickly [

38]. Therefore, despite improving the dispersion degree of the rubber compounds ingredients in the elastomer matrix, DmiBr and CTAB did not enhance the tensile properties of the vulcanizates. Hence, it would be necessary to optimize the content of DmiBr and CTAB in the composite to obtain both an improvement in the dispersion degree of HAP and an optimal crosslink density of the vulcanizates.

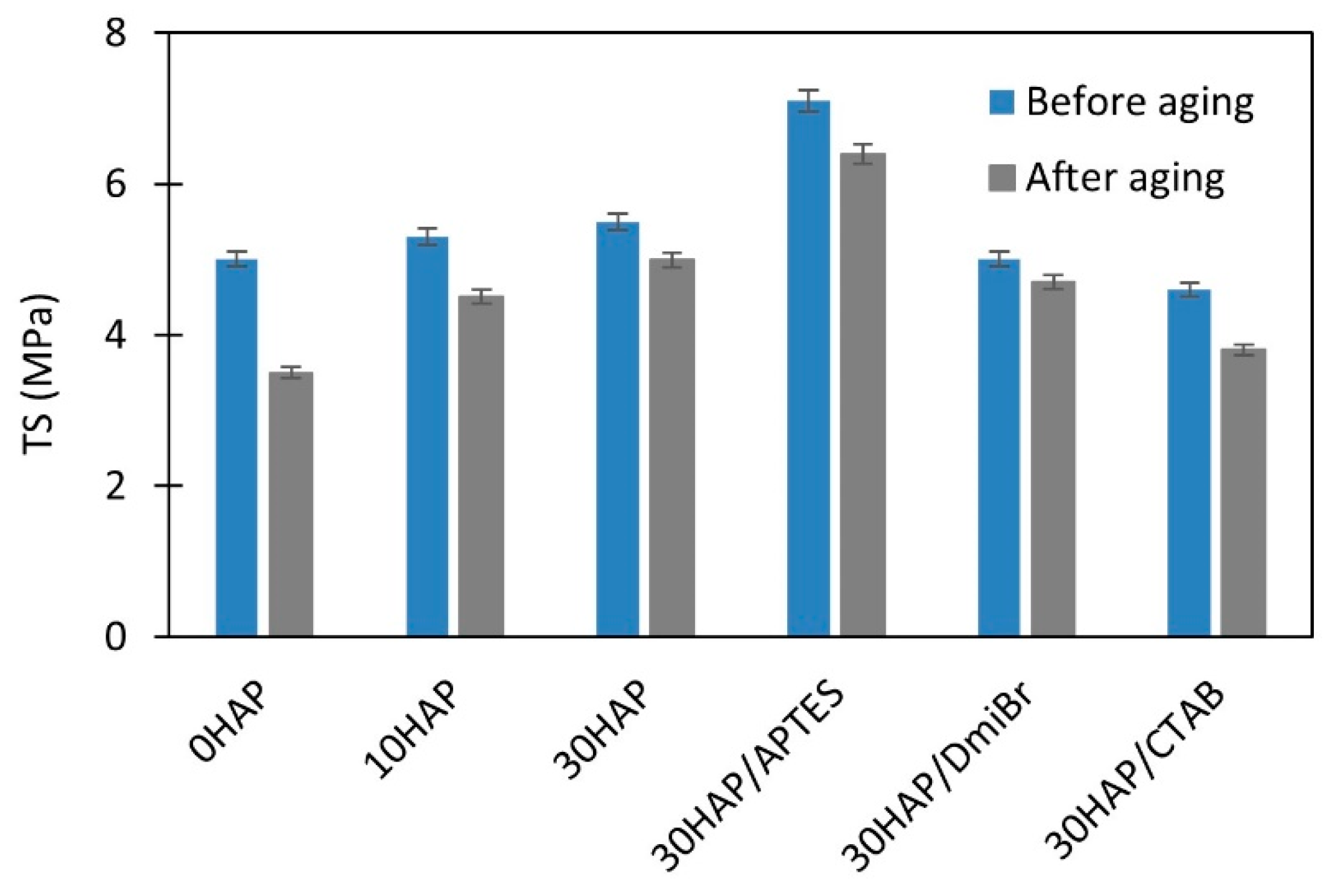

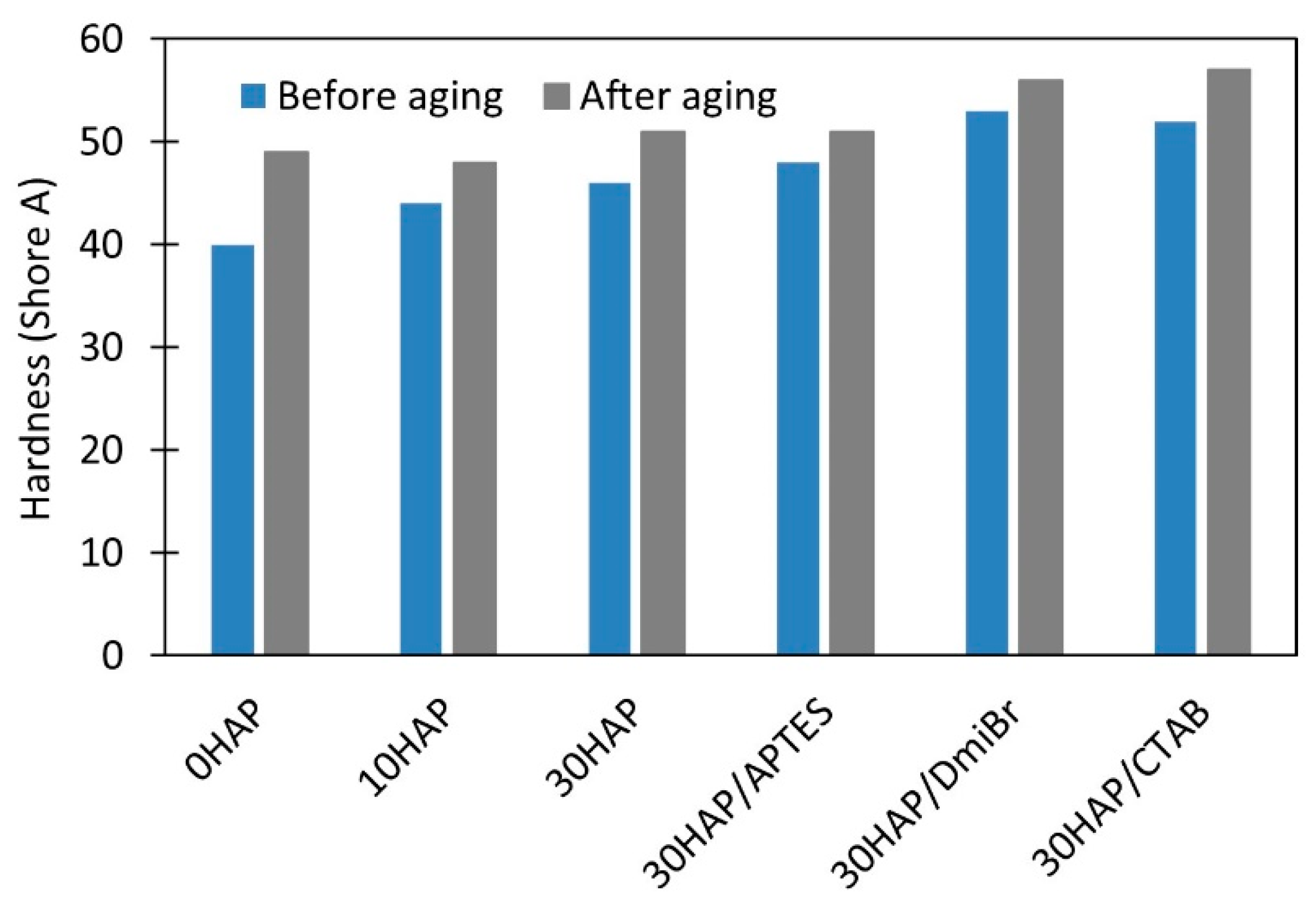

3.4. The Influence of Hydroxyapatite and Dispersants on the Thermo-Oxidative Aging Resistance of NBR Composites

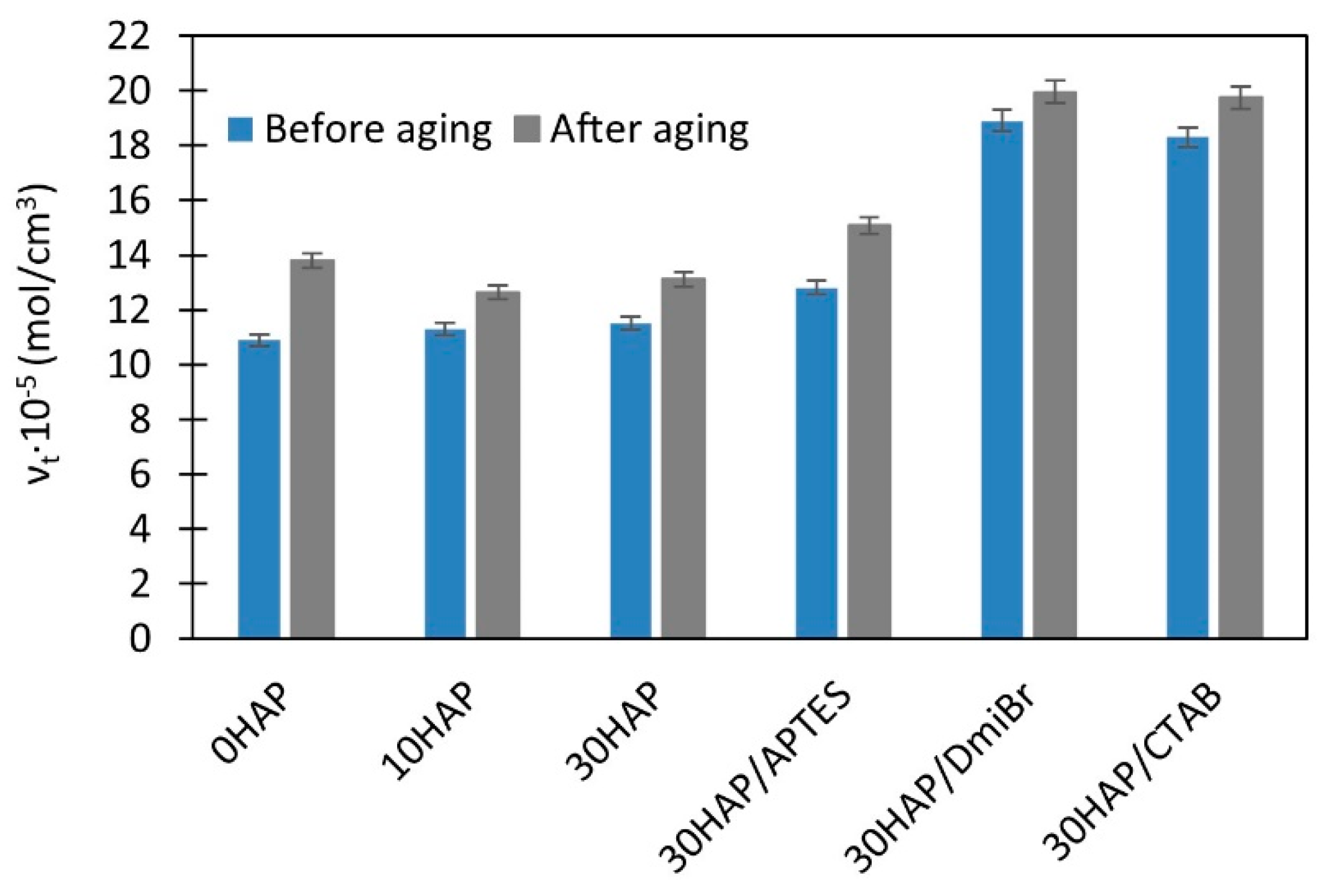

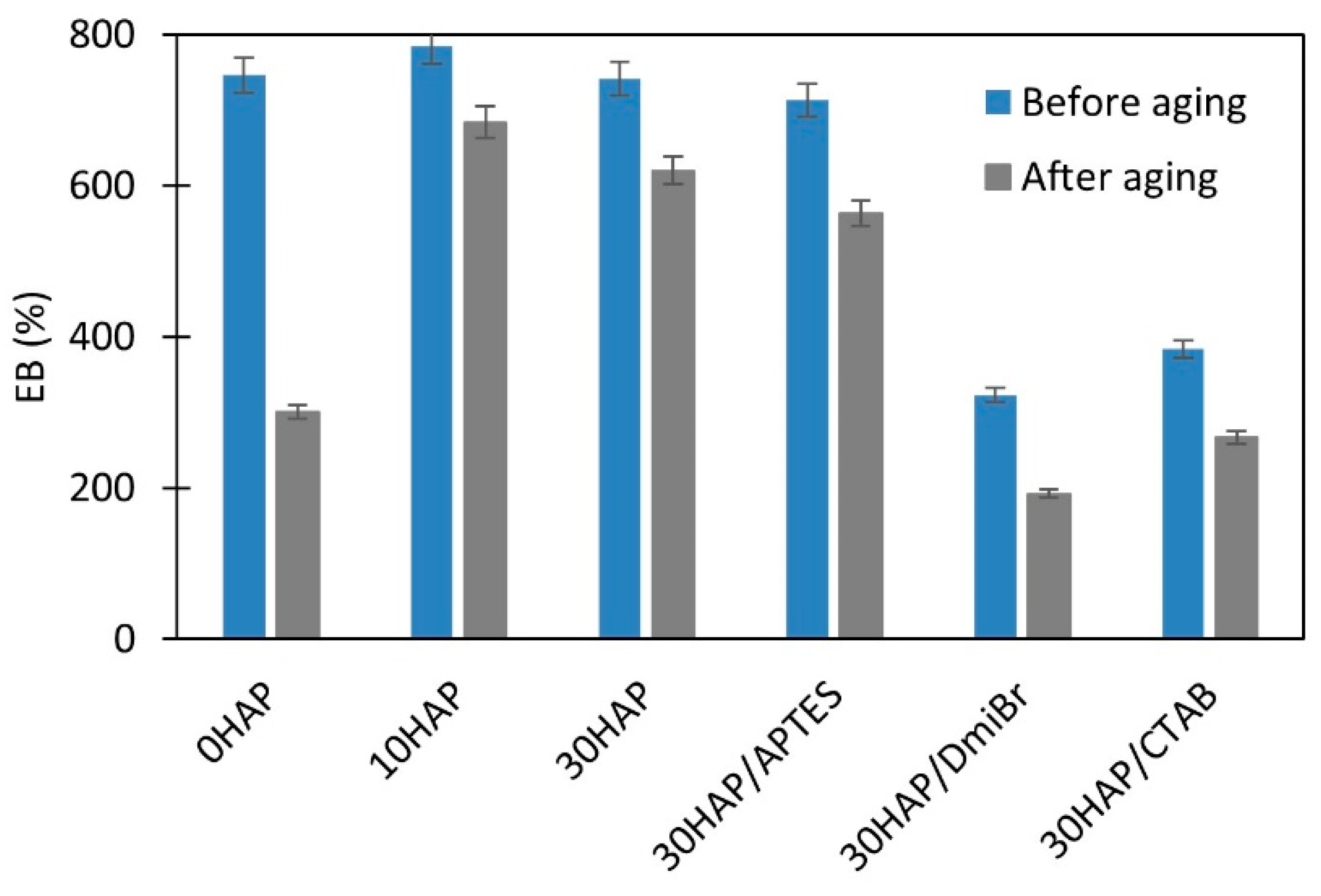

To investigate the resistance of vulcanizates to thermo-oxidative aging, measurements of ν

t and mechanical properties under static conditions were used. Resistance to thermo-oxidative aging is determined by the difference in the values of these parameters before and after aging. The results are presented in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

Prolonged exposure of NBR vulcanizates to high temperature during thermo-oxidative aging (100 °C, 7 days) caused a significant increase in the ν

t. This was particularly observed for the unfilled vulcanizate (

Figure 2). It results from the fact that rubber compounds are not vulcanized to the maximum crosslink density, but to the optimal ν

t to avoid over-crosslinking. For this reason, rubber composites usually vulcanize to a small extent during their use at high temperatures and during their thermo-oxidative aging at high temperatures. The consequence of the increase in ν

t of vulcanizates during aging are changes in their mechanical properties observed in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, i.e., significant increase in the hardness of the vulcanizates, and reduction in their TS and EB. Most importantly, the greatest changes in mechanical properties due to aging were obtained for the unfilled vulcanizate. Hence, it can be concluded that the addition of HAP significantly improved the resistance of NBR vulcanizates to thermo-oxidative aging. This was confirmed by the aging coefficient (A

f) values presented in

Table 5. The smaller the changes in TS and EB of vulcanizates occurred because of aging, the greater (closer to 1) A

f was achieved.

The unfilled NBR were characterized by significantly lower Af compared to vulcanizates filled with HAP, thus it exhibited poor resistance to thermo-oxidative aging. HAP highly improved the aging resistance of NBR. It should be noticed that Af increased from 0.28 for the unfilled vulcanizate to approximately 0.76 for 30HAP. APTES did not affect the aging resistance, whereas vulcanizates containing DmiBr or CTAB demonstrated slightly lower Af (of approximately 0.57) compared to 30HAP, but still much better than the unfilled NBR. The weaker resistance to aging of vulcanizates with DmiBr and CTAB compared to 30HAP was because they were over-crosslinked and therefore brittle before aging. Long-term exposure to elevated temperature during the aging process resulted in further crosslinking of these highly vulcanized materials and, consequently, further deterioration of their mechanical properties.

3.5. The Influence of Hydroxyapatite and Dispersants on the Dynamic Mechanical Properties of NBR Composites

In

Table 6 and

Figure 6 the results of DMA tests performed as a function of temperature are presented. Based on the DMA curves of the dependence of the mechanical loss factor (tan δ) on temperature, the glass transition temperature of NBR (T

g) was determined. Moreover, the values of tan δ were determined at the T

g and in the rubbery elastic region at temperatures of 25 °C (tan δ

25 °C) and 60 °C (tan δ

60 °C), respectively.

HAP did not significantly affect the Tg of NBR, which ranged from -19 °C to -18 °C. Similarly, the addition of dispersants did not have a significant effect on the Tg. Therefore, it can be concluded that neither HAP nor the dispersants used will have a significant impact on the operating temperature range of NBR vulcanizates in dynamic conditions.

Tan δ is determined as the ratio of the loss modulus to the storage modulus and represents the material's ability to dampen vibrations. The larger tan δ, the better damping properties of the material [

39]. Tan δ at T

g of the unfilled vulcanizate was 1.85. HAP, regardless of its amount, had no significant effect on the values of tan δ at T

g. However, vulcanizates containing dispersants, especially ionic liquid DmiBr and surfactant CTAB, were characterized by much lower tan δ at T

g compared to 30HAP. It was due to their higher crosslink density, because the greater the number of crosslinks, the more limited the mobility of elastomer chains and consequently the lower elasticity, and therefore worse damping properties.

Regarding the dynamic properties of vulcanizates in the rubbery elastic region, the tan δ at temperatures of 25 °C and 60 °C for the unfilled vulcanizate was 0.11. Therefore, it can be concluded that in the elastic state, the temperature did not have a significant impact on the damping properties of this material, because the differences in tan δ values are within the measurement error. HAP did not have a significant impact on the tan δ in the elastic state, and therefore on the material's ability to dampen vibrations. It was similar in the case of the silane application. On the other hand, vulcanizates with DmiBr and CTAB were characterized by lower tan δ values at 25 °C and 60 °C compared to 30HAP, which may indicate their slightly worse damping properties resulting from over-crosslinking.

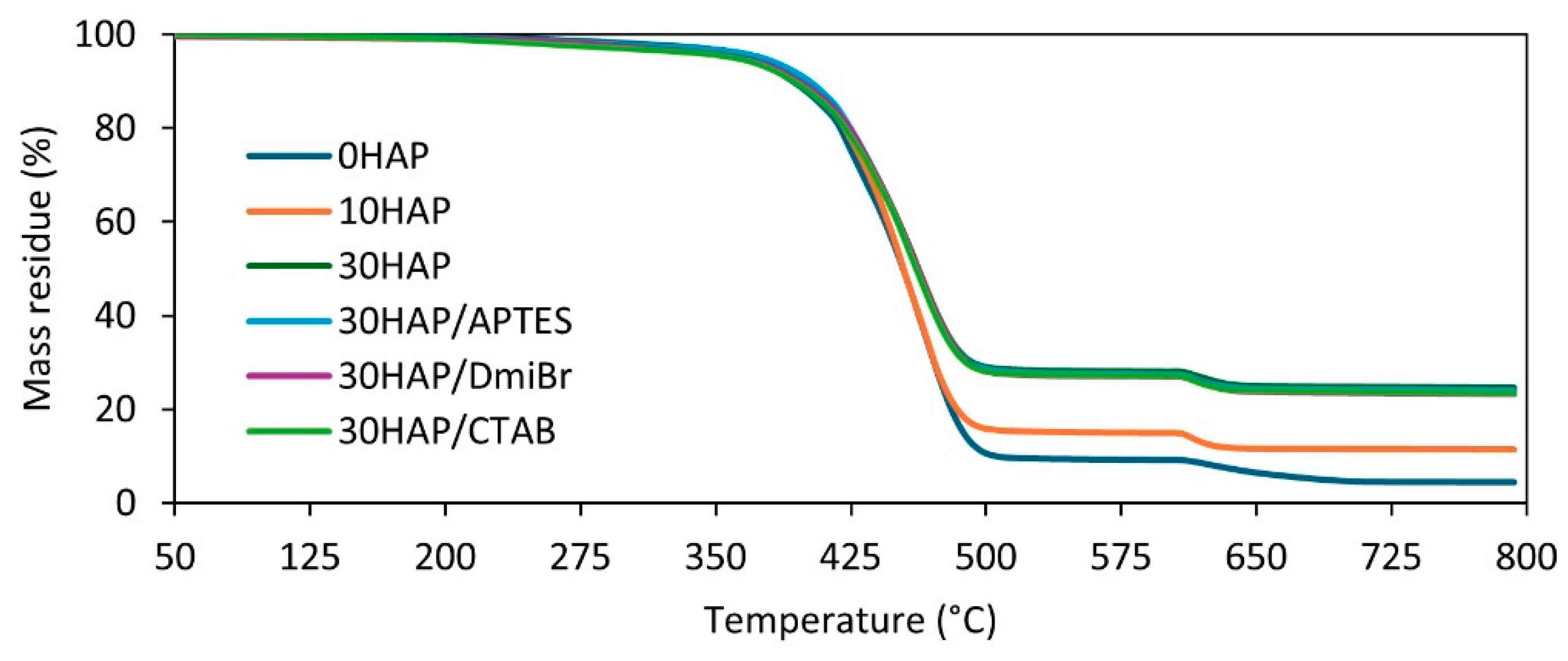

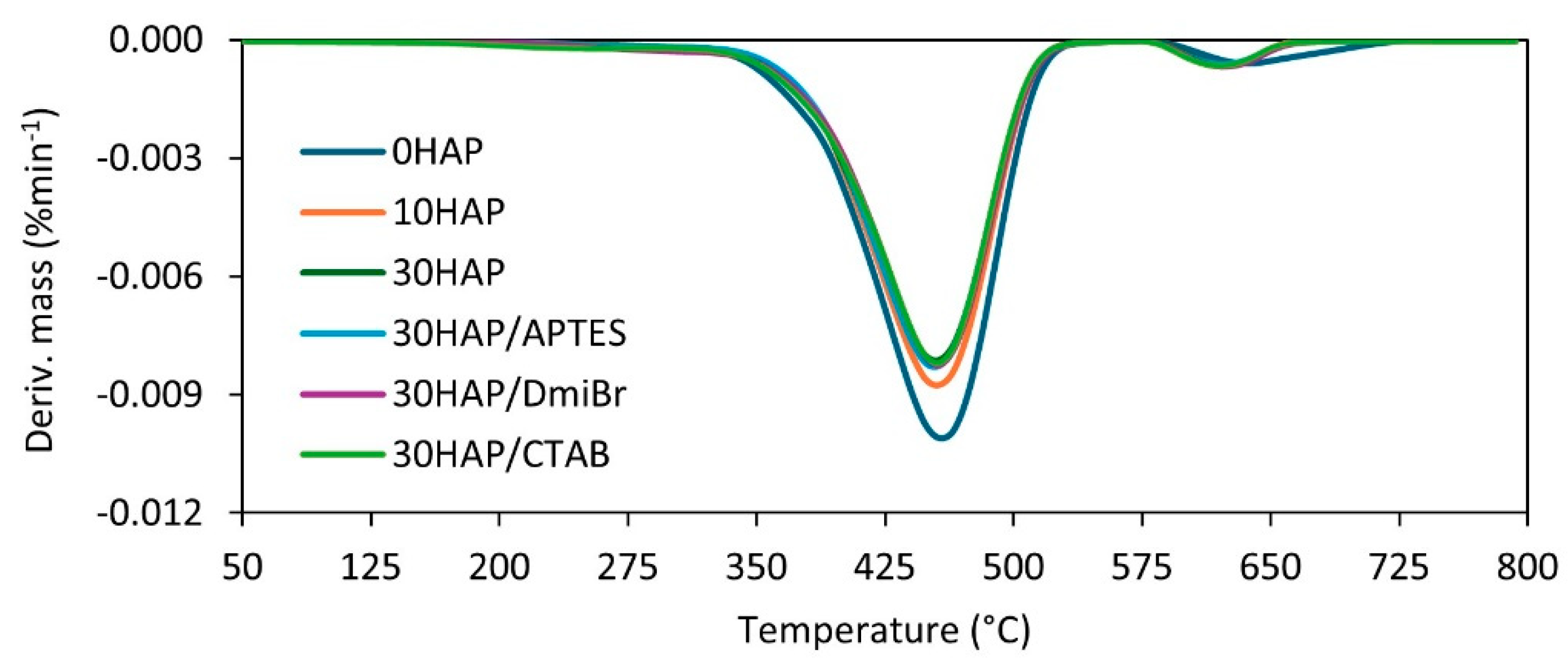

3.6. The Influence of Hydroxyapatite and Dispersants on the Thermal Stability of NBR Composites

HAP is characterized by high thermal stability [

40]. Therefore, in the next step of the research the influence of HAP on the thermal decomposition of NBR composites was studied using thermogravimetry (TG). Based on the data obtained, the following were determined: the temperature of the sample mass change by 5% (T

5%), the peak temperature on the mass change rate over time curve (T

DTG), which corresponds to the temperature at which the thermal decomposition of the material proceeds the fastest, the percentage mass loss at a temperature of 25- 600 °C (Δm

25-600 °C), the percentage mass loss at 600-800 °C (Δm

600-800 °C), as well as the percentage of mass that remained at 800 °C (R

800 °C). Results are presented in

Table 7 and

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

HAP slightly increased the onset decomposition temperature (T

5%) of NBR composites. A maximum increase of 8 °C was achieved for the 30HAP vulcanizate, since T

5% increased with the content of HAP in elastomer composite. The addition of dispersants, i.e., DmiBr and CTAB, resulted in a reduction in T

5% by 10-12 °C compared to 30HAP. It was due to the significantly lower thermal stability of pure DmiBr and CTAB compared to NBR [

41,

42,

43]. However, HAP and dispersants did not significantly affect the temperature of maximum decomposition rate (T

DTG), which ranged from 476 °C for the unfilled NBR to 473 °C for vulcanizates containing APTES and CTAB.

The first mass loss at temperatures from 25 °C to 600 °C corresponded to the pyrolysis of rubber and organic substances in argon. The percentage values of mass loss in this temperature range correlated very well with the HAP content. The higher the filler content, the smaller was the sample mass loss in this temperature range. As expected, the highest Δm25-600 °C was determined for the unfilled vulcanizate (approximately 91%). After supplying air to the measuring chamber of the TG analyzer in the temperature range of 600-800 °C, the residues were burned which resulted from the pyrolysis that took place in the first stage of thermal decomposition. HAP and its content had no significant effect on the Δm600-800 °C. After completion of the TG test, the residue at 800 °C consisted of ZnO and HAP, as well as ash remaining after burning the sample.

Most importantly, taking into account the obtained TG results, it can be concluded that HAP did not have a detrimental impact on the thermal stability of NBR vulcanizates.

3.7. The Influence of Hydroxyapatite and Dispersants on the Flammability of NBR Composites

Having established the influence of HAP and dispersants on the thermal behavior, we than investigated the effect of these additives on the flammability of NBR composites. Since NBR products, e.g. seals or hoses, are often used in environments with flammable liquids, their resistance to burning is very important from the point of view of fire safety. The results of flammability tests are presented in

Table 8.

It should be noted that the use of HAP reduced the flammability of NBR composites, as evidenced by lower HRR, THR and HRC of the vulcanizates filled with HAP compared to the unfilled benchmark. Moreover, these parameters decreased with increasing HAP content in NBR composite. The positive effect of HAP on the flame retardancy of NBR could result from the reduction in the transfer of heat, gases and gaseous products of thermal decomposition by a network formed by HAP particles dispersed in the elastomeric matrix. In addition, the polar–polar interaction between NBR rubber chains and HAP particles may facilitate the creation of a strong structure that reduced the flammability of vulcanizates compared to the unfilled NBR [

18]. Thus, the higher content of HAP, the lower was the flammability of the elastomer composite. It is very important for industrial applications of NBR products. On the other hand, dispersants increased the flammability of NBR composites compared to 30HAP. These additives are organic compounds, which contain combustible carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen atoms, which are the sources of the fuel and thus increase the HRR, THR and HRC compared to 30HAP. However, it is worth noting that the flammability of composites containing dispersants was still lower than that of the unfilled vulcanizate.

3.8. The Influence of Hydroxyapatite and Dispersants on the Resistance to Oils and Fuels of NBR Composites

The main advantage of NBR is its resistance to oils, fuels and fats. For this reason, the basic applications of NBR rubber are seals, washers and hoses used in pneumatics and hydraulics [

1]. Therefore, it was justified to investigate the influence of HAP and dispersants on the chemical resistance of NBR. Results are presented in

Table 9.

Most importantly, HAP had no detrimental effect on the chemical resistance of NBR composites. The swelling percentages determined in engine oil, hydraulic oil and gasoline were even slightly lower for the vulcanizates containing HAP compared to the unfilled benchmark. Moreover, dispersants did not significantly affected the oil and fuel resistance of NBR vulcanizates compared to 30HAP. Thus, HAP and the tested dispersants can be used without a negative impact on the key feature of NBR rubber that determines its industrial applications.

4. Conclusions

Hydroxyapatite can be successfully applied as a filler of NBR composites to strongly improve their resistance to thermo-oxidative aging, increase thermal stability and reduce the flammability, without detrimental effect on the mechanical performance, elasticity, chemical resistance and damping properties of the vulcanizates. This is particularly important because NBR is used primarily for the products, e.g., seals or hoses, operating in the environment of fuels and oils, i.e. flammable substances.

Silane (APTES), ionic liquid (DmiBr) and surfactant (CTAB) are efficient dispersants, which improve the dispersibility of HAP particles and curatives in the NBR elastomer matrix. The most homogeneous dispersion of HAP is ensured by DmiBr. Above all, HAP in combination with DmiBr and CTAB significantly boosts vulcanization, causing an approximately 9-fold shortening of the vulcanization time and a reduction in the vulcanization temperature by approximately 25% compared to NBR composites without these additives. This is of key importance for the industrial use of such systems to reduce energy consumption for vulcanization of rubber composites and consequently the production costs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.; methodology, M.M., A.S.-B. and P.R.; software, M.M. and P.R.; validation, M.M.; formal analysis, M.M. and P.R.; investigation, M.M., A.S.-B. and P.R.; resources, M.M.; data curation, M.M. and P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M.; visualization, M.M. and P.R.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, M.M. and P.R.; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Degrange, J.-M.; Thomine, M.; Kapsa, P.; Pelletier, J.M.; Chazeau, L.; Vigier, G.; Dudragne, G.; Guerbé, L. Influence of Viscoelasticity on the Tribological Behaviour of Carbon Black Filled Nitrile Rubber (NBR) for Lip Seal Application. Wear 2005, 259, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-H.; Moon, Y.-I.; Jung, J.-K.; Choi, M.-C.; Bae, J.-W. Influence of Carbon Black and Silica Fillers with Different Concentrations on Dielectric Relaxation in Nitrile Butadiene Rubber Investigated by Impedance Spectroscopy. Polymers 2022, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, J.; Clarke, B.; Freakley, P.K.; Sutherland, I. Compatibilising Effect of Carbon Black on Morphology of NR–NBR Blends. Plast. Rubber Compos. 2001, 30, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Yang, S.; Ouyang, X.; Hong, H.; Jiao, Y. Improvement in Mechanical Properties of NBR/AO60/MMT Composites by Surface Hydrogen Bond. Polym. Compos. 2020, 41, 2169–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, F.C.F.; Furtado, C.R.G.; Oliveira, M.G. Influence of the Surfactant on the Hydrotalcite Dispersion in NBR/LDH Composites Produced by Coagulation. Macromol. Symp. 2014, 343, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochoń, M.; Przepiórkowska, A. Innovative Application of Biopolymer Keratin as a Filler of Synthetic Acrylonitrile-Butadiene Rubber NBR. J. Chem. 2013, 787269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munusamy, Y.; Kchaou, M. Usage of Eggshell as Potential Bio-Filler for Arcylonitrile Butadiene Rubber (NBR) Latex Film for Glove Applications. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakasam, M.; Locs, J.; Salma-Ancane, K.; Loca, D.; Largeteau, A.; Berzina-Cimdina, L. Fabrication, Properties and Applications of Dense Hydroxyapatite: A Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2015, 6, 1099–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, R.O.; Bulut, N.; Kaygili, O. Hydroxyapatite Biomaterials: A Comprehensive Review of their Properties, Structures, Medical Applications, and Fabrication Methods. J. Chem. Rev. 2024, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, J.A.; Sagadevan, S.; Fatimah, I.; Hoque, M.E.; Lokanathan, Y.; Léonard, E.; Alshahateet, S.F.; Schirhagl, R.; Oh, W.C. Recent Advances in Natural Polymer-Based Hydroxyapatite Scaffolds: Properties and applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 148, 110360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, T.A. dos Santos, L.A. In Situ Synthesis and Characterization of Hydroxyapatite/Natural Rubber Composites for Biomedical Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 77, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.; Li, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Zhou, G.; Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Xu, W. Preparation and Characterization of Nano-hydroxyapatite/Silicone Rubber Composite. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 3307–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrasik, J.; Szustakiewicz, K.; Zaborski, M.; Haberko, K. Hydroxyapatite: An Environmentally Friendly Filler for Elastomers. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2008, 483, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihmath, A.; Ramesan, M.T. Fabrication, Characterization and Dielectric Studies of NBR/Hydroxyapatite Nanocomposites. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2017, 27, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureewong, N.; Injorhor, P.; Krasaekun, S.; Munchan, P.; Waengdongbang, O.; Wittayakun, J.; Ruksakulpiwat, C.; Ruksakulpiwat, Y. Preparation and Characterization of Acrylonitrile Butadiene Rubber Reinforced with Bio-Hydroxyapatite from Fish Scale. Polymers 2023, 15, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nihmath, A.; Ramesan, M.T. Hydroxyapatite as a Potential Nanofiller in Technologically Useful Chlorinated Acrylonitrile Butadiene Rubber. Polym. Test. 2020, 91, 106837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihmath, A.; Ramesan, M.T. Fabrication, Characterization, Dielectric Properties, Thermal Stability, Flame Retardancy and Transport Behavior of Chlorinated Nitrile Rubber/Hydroxyapatite Nanocomposites. Polym. Bull. 2021, 78, 6999–7018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihmath, A.; Ramesan, M.T. Studies on the Role of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles in Imparting Unique Thermal, Dielectric, Flame Retardancy and Petroleum Fuel Resistance to Novel Chlorinated EPDM/Chlorinated NBR Blend. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2020, 46, 5049–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihmath, A.; Ramesan, M.T. Development of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles Reinforced Chlorinated Acrylonitrile Butadiene Rubber/Chlorinated Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer Rubber Blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, e50189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

ISO 6502-3:2018; Rubber—Measurement of Vulcanization Characteristics Using Curemeters—Part 3: Rotorless Rheometer. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

-

ISO 11357-1:2016; Plastics—Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)—Part 1: General Principles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

-

ISO 37:2017; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic—Determination of Tensile Stress-Strain Properties. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

-

ISO 868:2003; Plastics and Ebonite—Determination of Indentation Hardness by Means of a Durometer (Shore Hardness). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

-

ISO 1817:2015; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic—Determination of Effect of Liquids. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Flory, P.J.; Rehner, J. Statistical Mechanics of Cross-linked Polymer Networks. II. Swelling. J. Chem. Phys. 1943, 11, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, I.; Kimura, S.; Iwama, M. Physical Constants of Rubbery Polymers. In Polymer Handbook, 4th ed.; Brandrup, J., Immergut, E.H., Grulke, E.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc: New York, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Setua, D.K.; Soman, C.; Bhowmick, A.K.; Mathur, G.N. Oil Resistant Thermoplastic Elastomers of Nitrile Rubber and High Density Polyethylene Blends. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2002, 42, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

ISO 188:2011; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic—Accelerated Ageing and Heat Resistance Tests. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Masek, A.; Zaborski, M.; Kosmalska, A.; Chrzescijanska, E. Eco-Friendly Elastomeric Composites Containing Sencha and Gun Powder Green Tea Extracts. C. R. Chim. 2012, 15, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heideman, G.; Datta, R.N.; Noordermeer, J.W.M.; van Baarle, B. Influence of Zinc Oxide During Different Stages of Sulfur Vulcanization. Elucidated by Model Compound Studies. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 95, 1388–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundrarajan, M.; Jegatheeswaran, S.; Selvam, S.; Sanjeevi, N.; Balaji, M. The Ionic Liquid Assisted Green Synthesis of Hydroxyapatite Nanoplates by Moringa Oleifera Flower Extract: A Biomimetic Approach. Mater. Des. 2015, 88, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.; Gao, Y.; Iqbal, F.; Ahmad, P.; Ge, R.; Nishan, U.; Rahim, A.; Gonfa, G.; Ullah, Z. Extraction of Biocompatible Hydroxyapatite from Fish Scales Using Novel Approach of Ionic Liquid Pretreatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 161, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Liang, Z.; Zhao, X. Preparation of Hydroxyapatite Nanofibers by Using IonicL as Template and Application in Enhancing Hydrogel Performance. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, A.P.F.; Idczak, G.; Tilkin, R.G.; Vandeberg, R.M.; Vertruyen, B.; Lambert, S.D.; Grandfils, C. Evaluation of Hydroxyapatite Texture Using CTAB Template and Effects on Protein Adsorption. Surf. Interfaces 2021, 27, 101565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Tjandra, W.; Chen, Y.Z.; Tam, K.C.; Ma, J.; Soh, B. Hydroxyapatite Nanostructure Material Derived Using Cationic Surfactant as a Template. J. Mater. Chem. 2003, 13, 3053–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, W.-J.; Wang, M.-C.; Hon, M.-H. Morphology and Crystallinity of the Nanosized Hydroxyapatite Synthesized by Hydrolysis Using Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) as a Surfactant. J. Cryst. Growth 2005, 2339–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predoi, S.-A.; Ciobanu, C.S.; Motelica-Heino, M.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Badea, M.L.; Iconaru, S.L. Preparation of Porous Hydroxyapatite Using Cetyl Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide as Surfactant for the Removal of Lead Ions from Aquatic Solutions. Polymers 2021, 13, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.E. Cross-Linking–Effect on Physical Properties of Polymers. J. Macromol. Sci. C 1969, 3, 69–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urayama, K.; Miki, T.; Takigawa, T.; Kohjiya, S. Damping Elastomer Based on Model Irregular Networks of End-Linked Poly(Dimethylsiloxane). Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.J.; Lin, F.H.; Chen, K.S.; Sun, J.S. Thermal Decomposition and Reconstitution of Hydroxyapatite in Air Atmosphere. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 1807–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowińska, A.; Maciejewska, M.; Guo, L.; Delebecq, E. Thermal Analysis and SEM Microscopy Applied to Studying the Efficiency of Ionic Liquid Immobilization on Solid Supports. Materials 2019, 12, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goworek, J.; Kierys, A.; Gac, W.; Borówka, A.; Kusak, R. Thermal Degradation of CTAB in As-Synthesized MCM-41. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2009, 96, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alneamah, M.; Almaamori, M. Study of Thermal Stability of Nitrile Rubber/Polyimide Compounds. Int. J. Mater.Chem. 2015, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of NBR composites: (a) 0HAP; (b) 10HAP; (c) 30HAP; (d) 30HAP/APTES; (e) 30HAP/DmiBr; (f) 30HAP/CTAB.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of NBR composites: (a) 0HAP; (b) 10HAP; (c) 30HAP; (d) 30HAP/APTES; (e) 30HAP/DmiBr; (f) 30HAP/CTAB.

Figure 2.

Effect of thermo-oxidative aging on the νt of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 2.

Effect of thermo-oxidative aging on the νt of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 3.

Effect of thermo-oxidative aging on the EB of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 3.

Effect of thermo-oxidative aging on the EB of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 4.

Effect of thermo-oxidative aging on the TS of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 4.

Effect of thermo-oxidative aging on the TS of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 5.

Effect of thermo-oxidative aging on the hardness of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 5.

Effect of thermo-oxidative aging on the hardness of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 6.

Mechanical loss factor (tan δ) as a function of temperature for NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 6.

Mechanical loss factor (tan δ) as a function of temperature for NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 7.

Thermograwimetric (TG) curves of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 7.

Thermograwimetric (TG) curves of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 8.

Derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Figure 8.

Derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves of NBR vulcanizates filled with HAP.

Table 1.

General recipes of the NBR composites, phr (parts per hundred of rubber).

Table 1.

General recipes of the NBR composites, phr (parts per hundred of rubber).

| Compound |

0HAP |

10HAP |

30HAP |

30HAP/APTES |

30HAP/DmiBr |

30HAP/CTAB |

| NBR |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| ZnO |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| St.A. |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

| Sulfur |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| MBT |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| HAP |

- |

10 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

| APTES |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

| DmiBr |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

| CTAB |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

Table 2.

Cure characteristics at 160 °C and crosslink density of NBR composites (Smin – minimum torque, ΔS – torque increase during vulcanization, t02 – scorch time, t90 – optimal vulcanization time, νt – crosslink density determined in toluene).

Table 2.

Cure characteristics at 160 °C and crosslink density of NBR composites (Smin – minimum torque, ΔS – torque increase during vulcanization, t02 – scorch time, t90 – optimal vulcanization time, νt – crosslink density determined in toluene).

| NBR compound |

Smin

(dNm) |

Smax

(dNm) |

∆S

(dNm) |

t02

(min) |

t90

(min) |

νt × 10−5

(mol/cm3) |

| 0HAP |

0.6±0.2 |

7.9±0.2 |

7.3±0.2 |

0.9±0.2 |

16±1 |

10.9±0.2 |

| 10HAP |

0.7±0.1 |

9.1±0.1 |

8.4±0.1 |

1.8±0.2 |

28±1 |

11.3±0.3 |

| 30HAP |

0.8±0.2 |

11.6±0.2 |

10.8±0.2 |

1.9±0.2 |

28±1 |

11.5±0.2 |

| 30HAP/APTES |

0.8±0.2 |

15.0±0.2 |

14.2±0.2 |

1.5±0.2 |

27±1 |

12.8±0.4 |

| 30HAP/DmiBr |

1.5±0.1 |

18.1±0.1 |

16.6±0.1 |

0.4±0.2 |

3±1 |

18.9±0.3 |

| 30HAP/CTAB |

1.3±0.2 |

17.5±0.2 |

16.2±0.2 |

0.4±0.2 |

4±1 |

18.3±0.4 |

Table 3.

Temperature (Tcross) and enthalpy (ΔHcross) of NBR compounds crosslinking determined by DSC (standard deviation: Tcross ± 2 °C; ΔHcross ± 1.0 J/g).

Table 3.

Temperature (Tcross) and enthalpy (ΔHcross) of NBR compounds crosslinking determined by DSC (standard deviation: Tcross ± 2 °C; ΔHcross ± 1.0 J/g).

| NBR compound |

Tcross (°C) |

-∆Hcross (J/g) |

| 0HAP |

153-243 |

9.7 |

| 10HAP |

167-245 |

14.5 |

| 30HAP |

169-249 |

13.9 |

| 30HAP/APTES |

140-176 |

14.6 |

| 30HAP/DmiBr |

129-175 |

15.0 |

| 30HAP/CTAB |

124-191 |

16.6 |

Table 4.

Tensile properties and hardness of NBR vulcanizates (SE300 – stress at a relative elongation of 300%; TS – tensile strength; EB – elongation at break; H – hardness).

Table 4.

Tensile properties and hardness of NBR vulcanizates (SE300 – stress at a relative elongation of 300%; TS – tensile strength; EB – elongation at break; H – hardness).

| NBR vulcanizate |

SE300

(MPa) |

TS

(MPa) |

EB

(%) |

H

(Shore A) |

| 0HAP |

1.9 ± 0.1 |

5.0 ± 0.4 |

746 ± 38 |

40 ± 1 |

| 10HAP |

2.0 ± 0.1 |

5.3 ± 0.3 |

785 ± 52 |

44 ± 1 |

| 30HAP |

2.1 ± 0.1 |

5.5 ± 0.6 |

742 ± 67 |

46 ± 1 |

| 30HAP/APTES |

2.6 ± 0.1 |

7.1 ± 0.6 |

713 ± 36 |

48 ± 1 |

| 30HAP/DmiBr |

4.0 ± 0.3 |

5.0 ± 0.8 |

323 ± 53 |

53 ± 1 |

| 30HAP/CTAB |

3.6 ± 0.1 |

4.6 ± 0.3 |

384 ± 27 |

52 ± 1 |

Table 5.

Thermo-oxidative aging coefficient (Af) of NBR vulcanizates.

Table 5.

Thermo-oxidative aging coefficient (Af) of NBR vulcanizates.

| NBR vulcanizate |

Af

(-) |

| 0HAP |

0.28 ± 0.05 |

| 10HAP |

0.74 ± 0.03 |

| 30HAP |

0.76 ± 0.05 |

| 30HAP/APTES |

0.71 ± 0.07 |

| 30HAP/DmiBr |

0.56 ± 0.05 |

| 30HAP/CTAB |

0.57 ± 0.03 |

Table 6.

Glass transition temperature (Tg) and mechanical loss factor (tan δ) of NBR vulcanizates.

Table 6.

Glass transition temperature (Tg) and mechanical loss factor (tan δ) of NBR vulcanizates.

| NBR vulcanizate |

Tg

(°C) |

tan δTg

(-) |

tan δ25°C

(-) |

tan δ50°C

(-) |

| 0HAP |

-18 ± 1 |

1.85 ± 0.05 |

0.11 ± 0.01 |

0.11 ± 0.01 |

| 10HAP |

-17 ± 1 |

1.83 ± 0.06 |

0.13 ± 0.02 |

0.13 ± 0.02 |

| 30HAP |

-17 ± 1 |

1.81 ± 0.06 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

| 30HAP/APTES |

-19 ± 1 |

1.73 ± 0.06 |

0.13 ± 0.01 |

0.11 ± 0.01 |

| 30HAP/DmiBr |

-17 ± 1 |

1.55 ± 0.08 |

0.10 ± 0.01 |

0.08 ± 0.01 |

| 30HAP/CTAB |

-17 ± 1 |

1.60 ± 0.05 |

0.09 ± 0.02 |

0.08 ± 0.02 |

Table 7.

Thermal stability of NBR vulcanizates (T5% - onset decomposition temperature, TDTG - DTG peak temperature, ∆m - total mass loss during thermal decomposition, R800 °C - the percentage of mass that remained at 800 °C).

Table 7.

Thermal stability of NBR vulcanizates (T5% - onset decomposition temperature, TDTG - DTG peak temperature, ∆m - total mass loss during thermal decomposition, R800 °C - the percentage of mass that remained at 800 °C).

| NBR vulcanizate |

T5%

(°C) |

TDTG

(°C) |

∆m25-600°C

(%) |

∆m600-800°C

(%) |

R800 °C

(%) |

| 0HAP |

365 ± 1 |

476 ± 1 |

90.6 ± 0.9 |

4.8 ± 0.5 |

4.6 ± 0.5 |

| 10HAP |

370 ± 1 |

475 ± 1 |

84.5 ± 0.6 |

3.5 ± 0.6 |

12.0 ± 0.6 |

| 30HAP |

373 ± 1 |

474 ± 1 |

71.5 ± 0.8 |

3.4 ± 0.4 |

25.1 ± 0.4 |

| 30HAP/APTES |

375 ± 1 |

473 ± 1 |

72.3 ± 0.9 |

3.6 ± 0.4 |

24.1 ± 0.4 |

| 30HAP/DmiBr |

363 ± 1 |

473 ± 1 |

72.6 ± 0.5 |

3.7 ± 0.5 |

23.7 ± 0.5 |

| 30HAP/CTAB |

361 ± 1 |

473 ± 1 |

72.8 ± 0.5 |

3.7 ± 0.5 |

23.5 ± 0.5 |

Table 8.

Flammability results for NBR vulcanizates (HRR—heat release rate; THRR—temperature of the maximum heat release rate; THR—total heat released; HRC—heat capacity).

Table 8.

Flammability results for NBR vulcanizates (HRR—heat release rate; THRR—temperature of the maximum heat release rate; THR—total heat released; HRC—heat capacity).

| NBR vulcanizate |

HRR

(W/g) |

THRR

(°C) |

THR

(kJ/g) |

HRC

(J/gK) |

| 0HAP |

411 |

463 |

28.4 |

364 |

| 10HAP |

309 |

467 |

26.6 |

293 |

| 30HAP |

276 |

472 |

24.2 |

277 |

| 30HAP/APTES |

340 |

460 |

25.4 |

330 |

| 30HAP/DmiBr |

309 |

476 |

26.2 |

300 |

| 30HAP/CTAB |

345 |

461 |

25.4 |

339 |

Table 9.

Chemical resistance of NBR vulcanizates (QEO – swelling percent in engine oil, QHO – swelling percent in hydraulic oil, QG – swelling percent in gasoline)

Table 9.

Chemical resistance of NBR vulcanizates (QEO – swelling percent in engine oil, QHO – swelling percent in hydraulic oil, QG – swelling percent in gasoline)

| NBR vulcanizate |

QEO

(%) |

QHO

(%) |

QG

(%) |

| 0HAP |

1.0 |

1.2 |

12.0 |

| 10HAP |

0.9 |

1.0 |

11.1 |

| 30HAP |

0.7 |

0.9 |

10.4 |

| 30HAP/APTES |

0.8 |

1.0 |

11.0 |

| 30HAP/DmiBr |

0.6 |

0.7 |

10.0 |

| 30HAP/CTAB |

0.5 |

0.7 |

9.9 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).