1. Introduction

In the intricate fabric of Bangladeshi culture, there is a unique and enduring community referred to as the Bede People, who are nomadic fishermen. In academic discourse, they are referred to as “River Gipsies” or “Water Gipsies” due to their itinerant lifestyle on the waterways (Maksud and Rasul, 2006; Islam et al., 2018a). The origins of the term “bede” are subject to historical discussion. Some scholars propose a connection to the ancient Bedouin people, while others argue for a link to the Mangta racial group of Arakan, Myanmar, who came to Bangladesh in the 1630s (Chowdhury, 1998; Moniruzzaman et al., 2023).The Bede people, who are culturally and socially apart from the mainstream Bengali groups, maintain their own language, which helps to strengthen their cultural connection as they travel over the waterways of Bangladesh. Their means of living are intricately connected to the river, since they partake in diverse customary vocations such as fishing, snake enchanting, jewelry and spice commerce, and ceremonial devotion (Cheung et al., 2009 Das, 2011; Islam et al., 2016). Although the Bede people play a crucial part in Bengali culture, they experience widespread marginalization and deprivation, with limited access to fundamental necessities such as food, healthcare, education, and housing.

Nomadic fishers, who are socioeconomically marginalized and socially excluded, frequently reside on the outskirts of society and their perspectives are typically disregarded in political discussions (Islam, 2011; Rahman et al., 2002). Fishing is not just a source of food for the Bede community, but it also carries significant social and cultural importance. It symbolizes more than simply a way to make a living, but rather a way of life for the community (Gatewood and McCay, 1988; Onyango, 2011; Islam et al., 2017). Nevertheless, their conventional livelihoods are progressively marginalized due to the process of modernization, technological progress, and evolving societal attitudes. Nomadic fishermen face challenges including illiteracy, limited family planning, and child marriage due to an average household size of around seven persons residing on a single boat (Maksud and Rasul, 2006; Das, 2013; Kuddus et al., 2020). Their ability to move on the waterways of Bangladesh, especially in places like Munshiganj, Shariatpur, Chandpur, Laxmipur, Bhola and Patuakhali, makes them susceptible to natural disasters, piracy, and economic difficulties. They are restless fishing tribes who travel in small boats over wetlands, rivers, and coastal areas (Drinkwater et al., 2010; Kuddus et al., 2021). They possess a higher level of technical expertise compared to non-nomadic fishermen. Nomadic fishers are exclusively engaged in fishing as their primary occupation, in contrast to other fishers. As a result, individuals who are involved in fishing operations have no other option for survival and must continue to engage in this occupation despite the challenges they face.

Historically, gypsies or nomadic fishers have been engaged in a continual cycle of migration, moving from one site to another without being able to establish any legal claim to the territory of the state. The majority of them do not own property rights, but recently a small number of affluent nomadic fishermen have obtained ownership of land. However, they seldom have the opportunity to employ external workers for fishing, as their family members are actively involved in the process of catching fish. Due to technical breakthroughs, infrastructural expansions, and advancements in medical research, the gap between rural and urban living has significantly decreased. While this transition has been beneficial for the general population, it has resulted in the decline of the nomadic community, endangering their old traditions and culture (Islam and Chuenpagdee, 2018). In contemporary times, the majority of individuals no longer have faith in the efficacy of spiritual healing services. Furthermore, due to the proliferation of smartphones and other digital gadgets, people have lost interest in traditional forms of entertainment such as snake charming or monkey performances.

Therefore, their conventional occupations have become obsolete in contemporary times, with the exception of fishing. Due to the prevailing poverty, a significant number of nomadic women have resorted to wandering the bustling city streets, seeking assistance from its inhabitants through begging. Approximately 80,000 nomads reside in Bangladesh, with a majority of them lacking literacy skills (Islam and Chuenpagdee, 2018). The cultural and traditional existence of this group is seriously threatened as a result of modernity, social pressures, and ecological changes in their surroundings. Nomadic communities also have numerous challenges as a result of natural calamities, such as the need to suspend fishing activities and the sinking of their boats owing to tidal surges. Due to the limited size of their boats, they are unable to venture into the estuary to harvest hilsa fish during the monsoon season. Occasionally, river pirates abduct them and request a sum of money as payment (Alam et al., 2023a). If individuals desire to borrow money from their relatives or neighbors, they will pledge their valued possessions, such as jewelry and other expensive items, as collateral. Under extremely challenging circumstances, they were pushed to sell their fishing equipment, boat engines, and other possessions. The proceeds from the sale forced them to work as crew members on boats belonging to other nomads (Islam, 2018).

In this context, understanding the challenges faced by nomadic fishers is crucial for developing targeted interventions that address their vulnerabilities and promote sustainable livelihoods. This paper explores the social exclusion, economic deprivation, and climate vulnerability of nomadic fishers in Bangladesh, shedding light on their unique struggles and advocating for inclusive policies that safeguard their rights and dignity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was carried out in the nomadic fishing settlements of Naria Upazila, located in the Shariatpur area of Bangladesh. The Naria Upazila, renowned for its vast network of waterways and abundant aquatic resources, offered an optimal environment for investigating the livelihood dynamics of itinerant fishers. The chosen communities in Naria Upazila consist mainly of professional fishermen who are actively involved in fishing throughout the year. Due to their close association with the waterways and their need on fishing for survival, they were crucial subjects for comprehending the complex socio-economic dynamics of nomadic fishing groups.

2.2. Data Collection

This study delves into the socio-economic landscape of nomad fishers, employing a mixed-method approach to capture the multifaceted dimensions of their livelihoods and vulnerabilities. The collecting of quantitative data focuses on economic variables that are crucial for ensuring sustainable lives. We collected data on income levels, spending habits, and contributions to the national GDP using surveys and structured interviews. The use of quantitative analysis allowed for the clear observation of economic trends and patterns that are essential for evaluating the community’s financial ability to recover from challenges. In addition to quantitative measures, qualitative approaches were used to clarify the social dynamics inside the Bede community. The study employed participant observation, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions (FGDs) to investigate the topics of social exclusion, vulnerabilities, and the likelihood of being excluded. The qualitative findings provided intricate viewpoints on the actual experiences and societal standing of nomadic fishermen, enhancing our comprehension of their socio-economic environment.

In addition, a comprehensive examination of the current body of literature strengthened the contextual accuracy of our results, guaranteeing consistency with established research and theoretical frameworks. The research approach was guided by a strong focus on ethical considerations, ensuring rigorous compliance with societal norms, confidentiality, and anonymity regulations. By adhering to ethical principles, our aim was to maintain the integrity and legitimacy of our research findings.

2.3. Data Analysis

The data gathered from the surveys was analyzed using MS Excel (Version 2021), utilizing descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages. In order to improve understanding, the results were visually shown using graphs and tables, providing visual depictions of the data. In order to verify the findings obtained from the quantitative analysis, a total of nine household interviews (three in each community) and three focus group discussions (FGDs) were carried out within the fishing communities of the study locations. The qualitative encounters provide supplementary insights and context to enhance the quantitative findings. By engaging in an iterative process of analyzing and validating data, we were able to gain a thorough grasp of the socio-economic dynamics and social vulnerability landscape across nomad fisher communities.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Belongings and Position of Nomad Fishers and Other Fishing Communities in Bangladesh

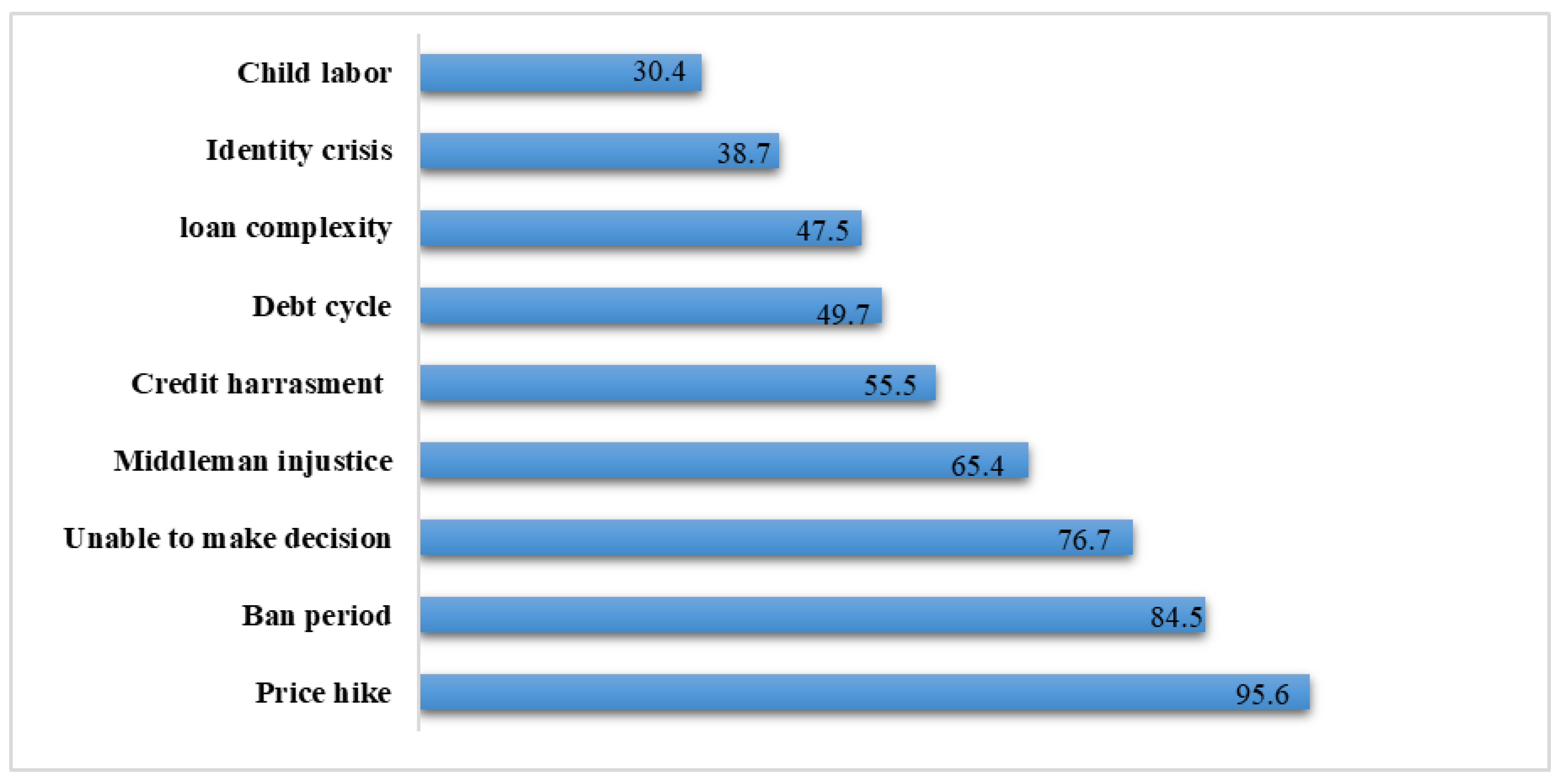

Within the riverine terrain of Bangladesh, which is marked by frequent floods and natural disasters, fishing communities play a crucial role in both the economy and the local food security. Within these communities, it is common to find nomadic fishers who traverse the country’s waterways, participating in both commercial and small-scale fishing operations alongside their counterparts who mostly operate on land. Although nomadic fishermen depend on fisheries for their livelihoods, they encounter specific difficulties and hold a distinctive position (38.7%) within the fishing industry (

Figure 1). Nomad fishermen have established collaborative partnerships with fishermen who operate on land, creating a network of reciprocal assistance and comprehension. Nevertheless, their ability to obtain loans and credit (55.5%) from official financial institutions is restricted because they do not possess land that can be used as collateral for mortgages (

Figure 1). Instead, they frequently rely on local informal lenders, commonly referred to as dadondar and bepari (65.4%), to fulfill their financial requirements (

Figure 1). Although informal loans offer immediate assistance, they frequently involve unfavorable conditions, such as reduced pricing for fish delivered to the lenders and high interest rates on borrowed cash, which worsen the economic vulnerability of nomadic fishermen (Sunny et al., 2023)

Curiously, it is worth noting that nomadic fishermen possess their own administrative authority, referred to as the Sarder, who plays a vital role in overseeing internal dynamics and settling disagreements within the community. Clan-based institutions enhance the unity and responsibility among nomadic fishers, making it easier for them to make decisions together and resolve conflicts (76.7%). The Sarder also manages the movement of itinerant fishermen, deciding how long they remain in different communities and arranging group travel plans. During periods of confrontation with sedentary fishers, influential individuals, or governmental authorities, it is common for nomadic fishers to seek sanctuary and assistance from beparis, who offer them refuge and safeguard them during fishing ventures. Nevertheless, nomadic fishers frequently encounter economic difficulties, which compel them to sell fish directly to customers at reduced costs in order to alleviate financial burdens particularly during fishing ban (84.5%). In order to improve the economic resilience and social inclusion of nomadic fishers, it is important to take into account the complex factors at play and utilize the existing social structures and networks to support sustainable livelihoods and well-being within the community (Alam et al., 2023b).

3.2. Fishing as a Sustainable Profession for Nomads

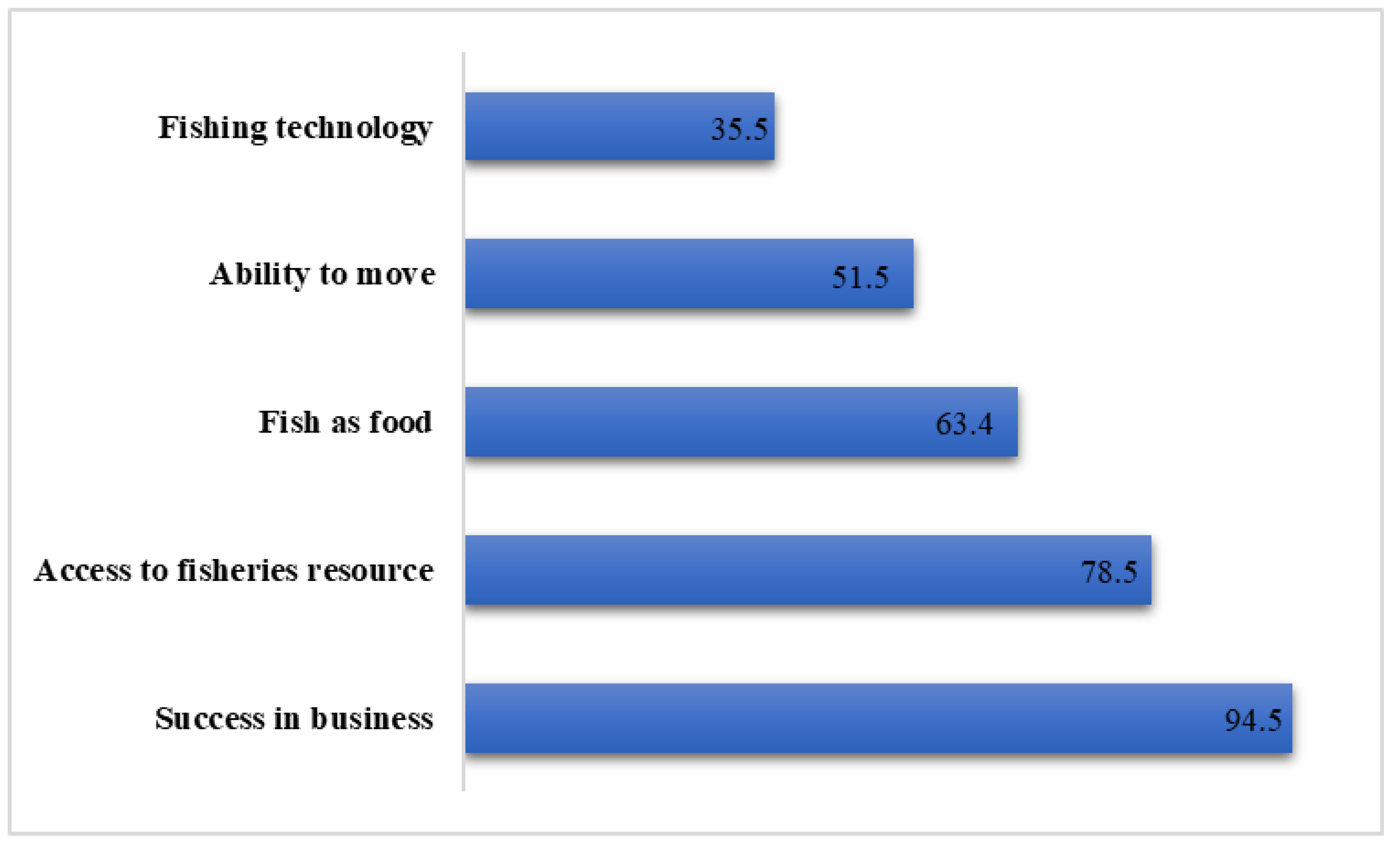

In Bangladesh, nomadic people make a living from a range of sources, such as snake charmers and conventional medical procedures. Among these, however, fishing stands out as being more sustainable. Success in business (94.5%) brings benefits in terms of relationships and subjectivity in addition to money (

Figure 2). Nomadic fishermen place great emphasis on the ability to move to better fishing spots, especially when faced with challenging conditions like high salinity levels in rivers. Access to freshwater species, which are required for everyday tasks like cooking and bathing, is ensured by this mobility. Because they dwell near the ocean, they have constant access to fisheries resources (78.5%), which allows them to meet their protein demands and provide food security.Since 80–90% of the protein in their diet comes from the fish they catch, it is obvious that they are dependent on fishing. Depending on fishing technology and season, nomadic fisherman can make between

$80 and

$220 per month. They find fulfilment in their profession. During peak seasons, daily earnings could surpass

$260, particularly when catching in-demand species like hilsa.With this income, they can save money, repair or purchase fishing boats, renovate their shelters, and even purchase land for longer-term habitations. Nomadic fisherman also creates jobs in the area by hiring people from the land for fishing operations, processing, marketing, and transportation.Their deep ecological knowledge helps them find good fishing areas, which allows them to out fish local non-nomadic fisherman using similar gear. Despite the risks and uncertainty, they encounter, nomadic fishermen never waver in their commitment to their craft or in their sense of cultural identity. They find comfort and happiness in continuing their family’s fishing tradition, which provides them with a sense of purpose and community in addition to financial assistance.

3.3. Social Exclusion and Vulnerability

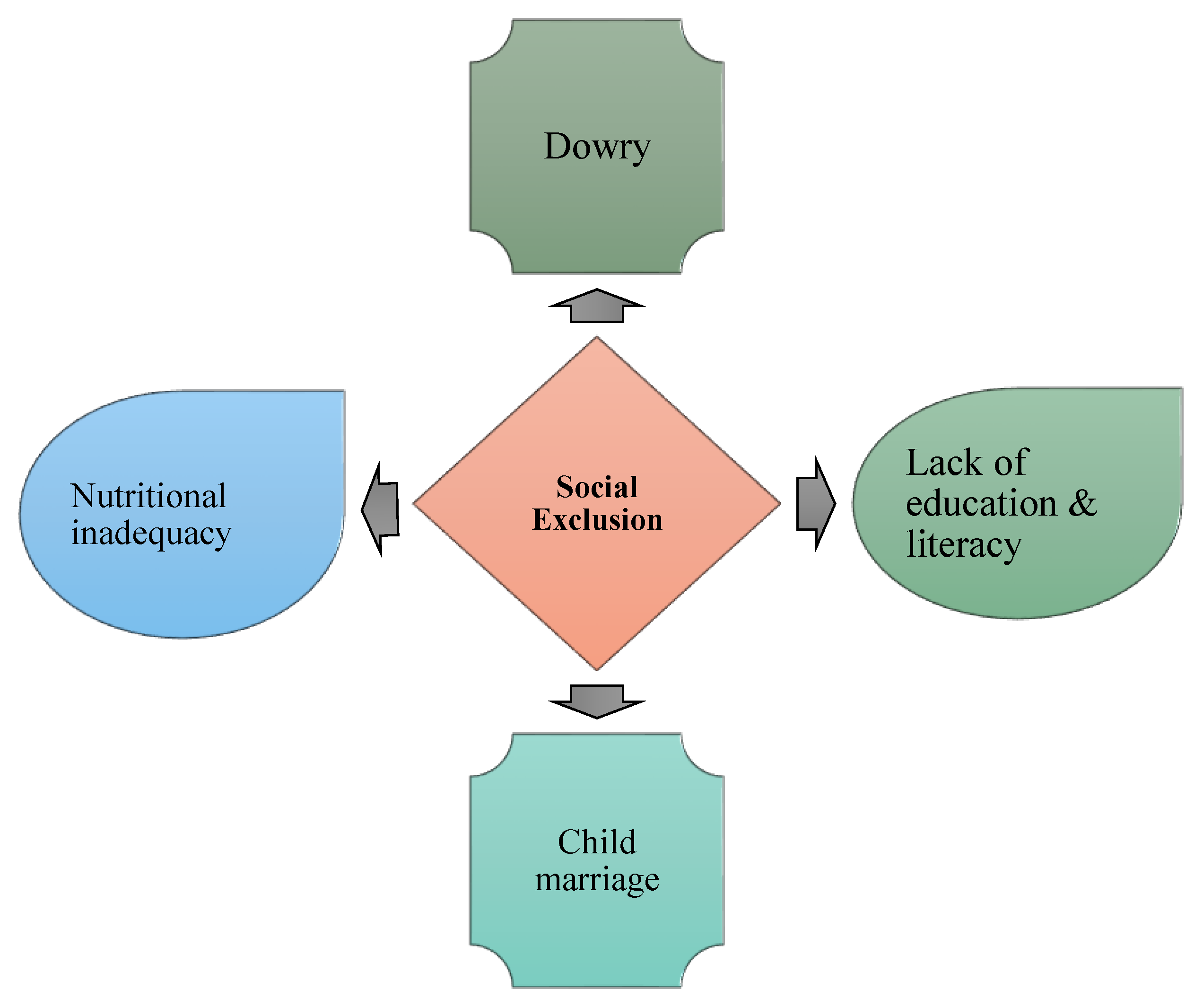

Nomadic fishers are gradually being reticulated in every stage of our society and are the most neglected marginalized community. Regularly they pass through tremendous economic, social and cultural exclusion just because of their lower position in society (

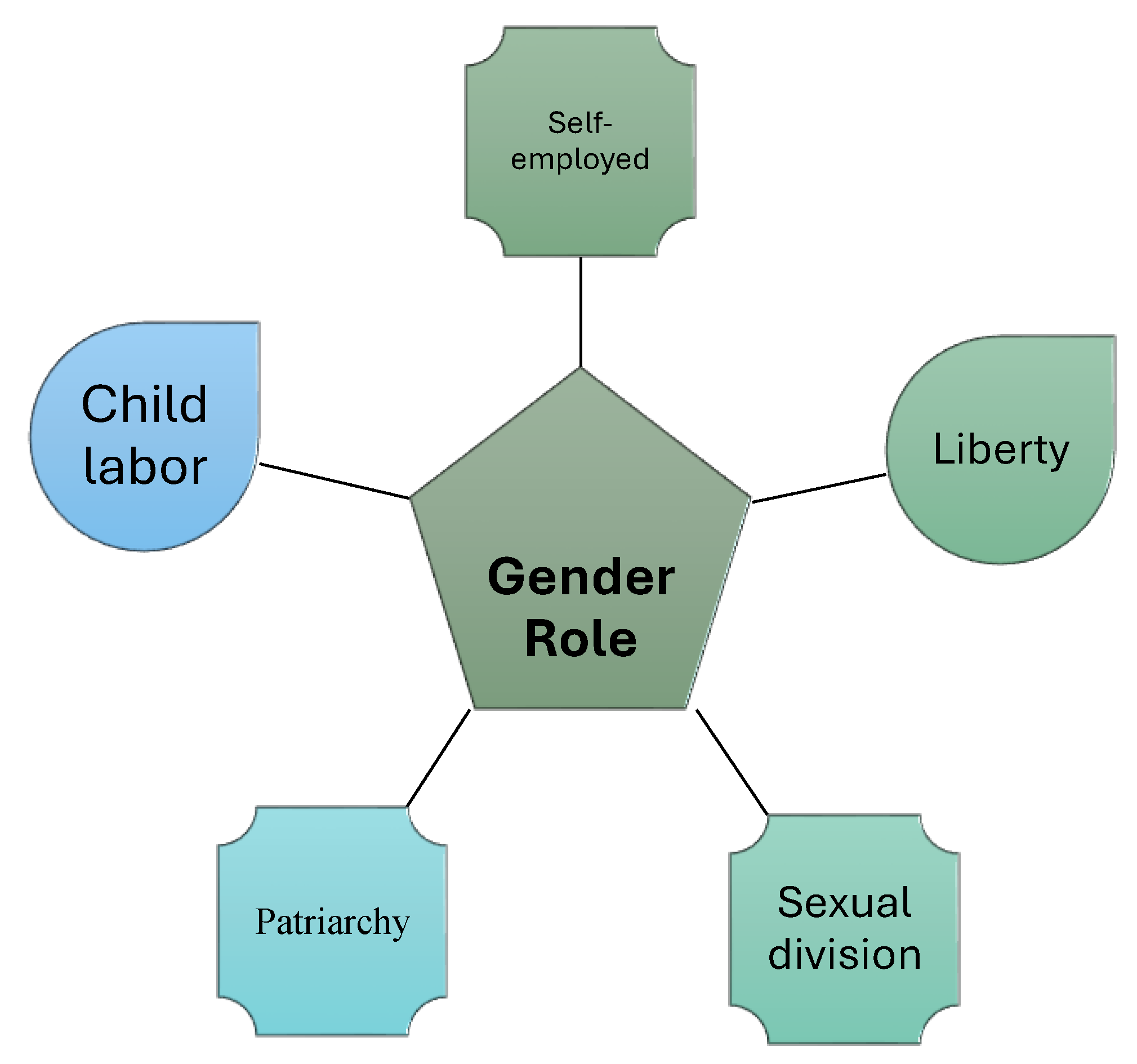

Figure 3). But through so many things, it is to be hoped that the nomads gain their rights to vote in 2009. It’s such a great achievement for them to get initial recognition from the state throughout voting on national election. Bangladesh is a conservative Muslim patriarchic society (Hossain et al., 2023a). Here, wage earners and family-owned men and mainstream societies try to avoid direct entry of nomadic communities. Despite strictly practicing religious affairs here nomadic women get enormous liberty, self-employment and individual mobility to work freely (

Figure 4). Generally, fisher indicate men who is consider catching, collect and selling fishes in market but this scenario is totally changed in nomadic fishing communities. Here, women play a significant role in fishing related activities along with men. Basically, non-nomadic fishing societies where women’s prime duties are to maintain household chores and fostering children, but their women engaged themselves in fishing with their husbands and family. Usually, men involve in fish catching and trading to the locality to earn money whereas women accomplishing rest of the work like steering boats, recasting equipment and dried nets in the riverside. Even sometimes they are engaging door to door selling fish to the neighbors. During the development of patriarchal small-scale fishing society, all the money and assets were reserved for men and women’s participation was marked as family members or, in most cases voluntarily. Beside these women are doing all other responsibilities of the families (Hussain et al., 2023b). As a result, they are being despoiled of taking interregnum even though the times of pregnancy they ought to work hard to survive. On the other hand, non-fisher nomadic families where women are the earning members seems to be seen as older then real age whilst men help to look after family.

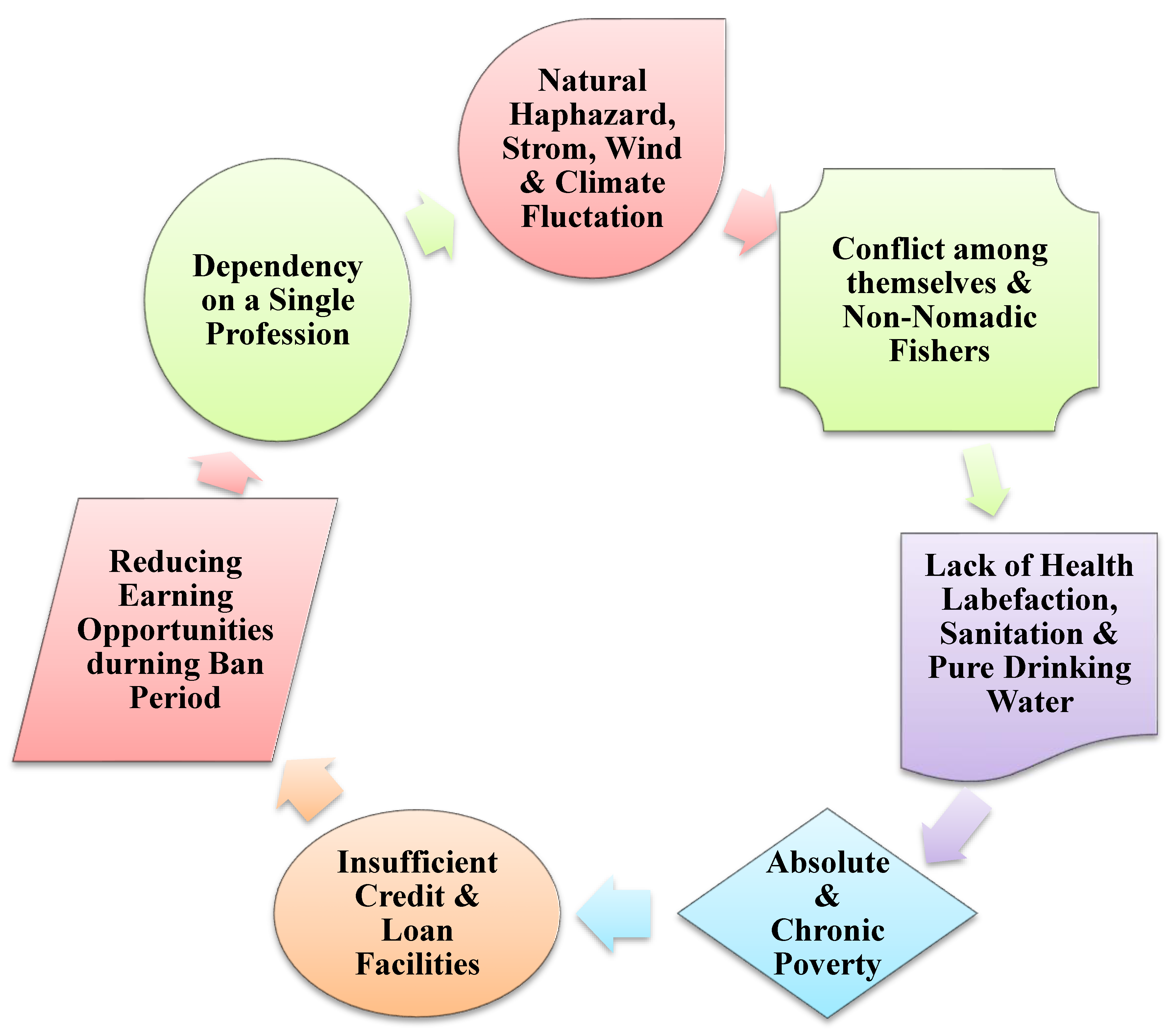

Nomadic fishers are living riverside by birth, develop a dynamic ecological sagacity and have sharp ideas of its resource, fish sanctuaries and atmosphere. They are tremendously facing different types of climatic catastrophe, storms, winds, cyclone and tides (Islam et al., 2018b; Chakma et al., 2022). During haphazard condition women are more vulnerable enduring crisis of pure drinking water, poor sanitation and health labefaction. Polygamy, dowry, child marriage, patriarchy, adolescent labor are universal practices among majority of the nomadic fishers (Kuddus et al., 2022; Bari et al., 2023; Rana et al., 2023). Undoubtedly these worst victims are nomadic women which badly affecting their reproductive age and mental health (Islam and Chuenpagdee, 2017). Some major vulnerabilities of nomadic fisher are shown in (

Figure 05).

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

The nomads who have fishing gear and access to fishing grounds in the river earn better, but they are deprived of other well-being criteria such as literacy and health and nutritional standards. Their livelihood cannot be sustainable without these well-being criteria and proper steps should be taken to implement these in the nomad community. Besides, their mode of living in an isolated place on a houseboat makes their life more vulnerable and there is a risk of exclusion. Proper interventions are needed for both state and non-state actors for improving this community as they have specialized fishing skills and can form patron-client relationships. Landlessness as an instrumental deprivation for nomad people, so their access to homestead land should be given priority by the policy maker (Sen, 2000) because most of the nomads view their livelihood sustainability as linked to sedentary dwellings on land. Their entitlement to land will ensure their sanitation and education services. For this, the newly developed island (Char) into the river could be a suitable place for their rehabilitation. Most of the nomadic fishers expect to live a land in a permanent basis and very few are ready to give up their fishing profession. So, their access should be secured for sustainable fishing practices which will help them to achieve further material success. For their upward mobility and poverty alleviation, education will play an important role. It will remove child labor and children dropping out from school. For this, government can start ‘Conditional Cash Transfer’ for enhancing school attendance, thus intergenerational transfer of poverty will be prevented (Islam, 2018). Due to ban period, poor nomadic fishers should not be suffered for food and any other daily necessities. The government needs to be compensated for their lost income. The government should bring the nomad people under the incentive program of hilsha fisheries to tackle their ‘hunger period’ during ban periods of hilsha fishing as they have no alternative income generating activities other than fishing. Besides, proper measure should be taken to reduce dependency on unstable fisheries as the sole source of income by expanding opportunities for alternative occupations. For this, the design of livelihood interventions needs to be consulted with the communities rather than only by the implementing agencies (Pomeroy et al. 2017). State and non-state agencies should implement a holistic approach to livelihood intervention, not only focusing on production but also including all parts of the value chain.

References

- Alam, K., Jahan, N., Chowdhury, R., Mia, M.T., Saleheen, S., Hossain, N.M & Sazzad, S.A. (2023a). Impact of Brand Reputation on Initial Perceptions of Consumers. Pathfinder of Research, 1 (1), 1-10.

- Alam, K., Jahan, N., Chowdhury, R., Mia, M.T., Saleheen, S., Sazzad, S.A. Hossain, N.M & Mithun, M.H. (2023b). Influence of Product Design on Consumer Purchase Decisions. Pathfinder of Research, 1 (1), 23-36.

- Arefeen, H. K. S. (1992). Sub-culture: Society of Bangladesh., Samaj Nirikhon Kendra, Dhaka, pp.1-14.

- Bari, K. F., Salam, M. T., Hasan, S. E., & Sunny, A. R. (2023). Serum zinc and calcium level in patients with psoriasis. Journal of Knowledge Learning and Science Technology ISSN: 2959-6386 (online), 2(3), 7-14.

- Bebbington, A. (1999). Capitals and capabilities: a framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Dev. 27(2):2021–2044.

- Chakma, S., Paul, A.K., Rahman, M.A., Hasan, M.M., Sazzad, S.A. & Sunny, A.R. (2022). Climate Change Impacts and Ongoing Adaptation Measures in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries. 1;26(2):329-48. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W. W., Lam, V. W., Sarmiento, J. L., Kearney, K., Watson, R., & Pauly, D. (2009). Projecting global marine biodiversity impacts under climate change scenarios. Fish and fisheries, 10(3), 235-251.

- Das, B. (2013). Rough sailing for Bangladesh river-gypsies. http://www.Aljazeera.Com/indepth/features/ 2013/01/201312181138776540.Html. Accessed 8 July 2015.

- Drinkwater, K. F., Beaugrand, G., Kaeriyama, M., Kim, S., Ottersen, G., Perry, R. I., ... & Takasuka, A. (2010). On the processes linking climate to ecosystem changes. Journal of Marine Systems, 79(3-4), 374-388.

- Gatewood, J. B., McCay, B. J. (1988). Job satisfaction and the culture of fishing: A comparison of Six New Jersey Fisheries. MAST 1(2):103–128. [CrossRef]

- Gudeman, S. (2001). The anthropology of economy. Blackwell, Oxford.

- Halder, S. (2012). The Bede Community of Bangladesh: a socio-legal study. North Univ. Law 3:76–86.

- Hossain Ifty, S.M., Ashakin, M.R., Hossain, B., Afrin, S., Sattar, A., Chowdhury, R., Tusher, M.I., Bhowmik, P.K., Mia, M.T., Islam, T., Tufael, M. & Sunny, A.R. (2023a). IOT-Based Smart Agriculture in Bangladesh: An Overview. Applied Agriculture Sciences, 1(1), 1-6. 9563, 10.25163/agriculture.119563.

- Hossain Ifty, S.M., Bayazid, H., Ashakin, M.R., Tusher, M.I., Shadhin, R. H., Hoque, J., Chowdhury, R. & Sunny, A.R. et al. (2023b). Adoption of IoT in Agriculture - Systematic Review, Applied Agriculture Sciences, 1(1), 1-10, 9676.

- Islam, M. M. (2011). Living on the margin: the poverty-vulnerability nexus in the small-scale fisheries of Bangladesh. In: Jentoft S, Eide A (eds) Poverty mosaics: Realities and prospects in small-scale fisheries. Springer Science+Business Media, Dordrecht, pp 71–95.

- Islam, M. M. (2018). Boat, Waters and Livelihoods: ―A Study on Nomadic Fishers in the Meghna River Estuary of Bangladesh.

- Islam, M. M., Chuenpagdee, R. (2018). Nomadic fishers in the hilsa sanctuary of Bangladesh: The importance of social and cultural values for well-being and sustainability. In Social Wellbeing and the Values of Small-Scale Fisheries; Springer: Cham, Swizerland,; pp. 195–216.

- Islam, M. M., Islam, N., Mostafiz, M., Sunny, A. R., Keus, H. J., Karim, M., ... & Sarker, S. (2018a). Balancing between livelihood and biodiversity conservation: A model study on gear selectivity for harvesting small indigenous fishes in southern Bangladesh. Zoology and Ecology, 28(2), 86-93.

- Islam, M. M., Islam, N., Sunny, A. R., Jentoft, S., Ullah, M. H., & Sharifuzzaman, S. M. (2016). Fishers’ perceptions of the performance of hilsa shad (Tenualosa ilisha) sanctuaries in Bangladesh. Ocean & Coastal Management, 130, 309-316.

- Islam, M. M., Shamsuzzaman, M. M., Sunny, A. R., & Islam, N. (2017). Understanding fishery conflicts in the hilsa sanctuaries of Bangladesh. Inter-Sectoral Governance of Inland Fisheries; Song, AM, Bower, SD, Onyango, P., Cooke, SJ, Chuenpagdee, R., Eds, 18-31.

- Islam, M. M., Sunny, A. R., Hossain, M. M., & Friess, D. A. (2018b). Drivers of mangrove ecosystem service change in the Sundarbans of Bangladesh. Singapore Journal of tropical geography, 39(2), 244-265.

- slam, M.M. and Chuenpagdee, R. (2017). Nomadic fishers in the hilsa sanctuary of Bangladesh: The importance of social and cultural values for wellbeing and sustainability, in D.S. Johnson et al. (eds.), Social Wellbeing and the Values of Small-Scale Fisheries. MARE Publication Series 17. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M., Islam, N., Sunny, A.R., Jentoft, S., Ullah, M.H., Sharifuzzaman, S.M. (2016). Fishers perceptions of the performance of hilsa shad (Tenualosa ilisha) sanctuaries in Bangladesh, Ocean & Coastal Management 130: 309- 16.

- Islam, M.M., Shamsuzzaman, M.M., Sunny, A.R., Islam N. (2017). Understanding fishery conflicts in the hilsa sanctuaries of Bangladesh, in A.M. Song, S.D. Bower, P. Onyango, S.J. Cooke and R. Chuenpagdee (eds.), Intersectoral Governance of Inland Fisheries. TBTI Publication Series, E-01/2017. St. John’s, Canada: Too Big to IgnoreWorld Fish.

- Jentoft, S. (2007). In the power of power: the understated aspect of fisheries management. Hum Orga 66(4):426–436.

- Jentoft. S., Eide. A., Bavinck, M., Chuenpagdee, R., Raakjær, J. (2011). A better future: prospects for small-scale fishing people. In: Poverty mosaics: Realities and prospects in small-scale fisheries. Springer.

- Khan, J. A. (2006). “Bedey”, http://en.banglapedia.org/index. php?title=bede&oldid=18063. Accessed 8 September 2017.

- Khan, M. I., Islam, M. M., Kundu, G. K., & Akter, M. S. (2018). Understanding the Livelihood Characteristics of the Migratory and Non-Migratory Fishers of the Padma River, Bangladesh. Journal of Scientific Research, 10(3).

- Kuddus, M. A., Alam, M. J., Datta, G. C., Miah, M. A., Sarker, A. K., & Sunny, M. A. R. (2021). Climate resilience technology for year round vegetable production in northeastern Bangladesh. International Journal of Agricultural Research, Innovation and Technology (IJARIT), 11(2355-2021-1223), 29-36.

- Kuddus, M. A., Datta, G. C., Miah, M. A., Sarker, A. K., Hamid, S. M. A., & Sunny, A. R. (2020). Performance study of selected orange fleshed sweet potato varieties in north eastern bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol, 5, 673-682.

- Kuddus, M. A., Sunny, A. R., Sazzad, S. A., Hossain, M., Rahman, M., Mithun, M. H., ... & Raposo, A. (2022). Sense and Manner of WASH and Their Coalition with Disease and Nutritional Status of Under-five Children in Rural Bangladesh: A Cross-Sectional Study. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 890293.

- Maksud, A. K. M., Rasul, G. (2006). The Nomadic Bede Community and their mobile school program. The paper presented in the conference on “What Works for the Poorest: Knowledge, Policies and Practices”, jointly organized by BRAC, Chronic Poverty Research Centre Partnership and Brooks World Poverty Institute, University of Manchester, BRAC Centre for Development Management (BCDM), Gazipur. Bangladesh.

- Moniruzzaman, Sazzad, S. A., Hoque, J., & Sunny, A. R. (2023). Influence of Globalization on Youth Perceptions on ChangingMuslim Rituals in Bangladesh. Pathfinder of Research, 1 (1), 11-22.

- Onyango, P. O. (2011). Occupation of last resort? Small-scale fishing in Lake Victoria, Tanzania. In: Jentoft S, Eide A (eds) Poverty mosaics: Realities and prospects in small-scale fisheries. Springer Science+Business Media B.V, Dordrecht, pp 97–124.

- Pomeroy, R., Ferrer A. J., Pedrajas, J. (2017). An analysis of livelihood projects and programs for fishing communities in the Philippines, Marine Policy 81: 250- 55.

- Rahman, M. M., Haque, M. M., Akhteruzzamam, M., Khan, S. (2002). Socioeconomic features of a traditional fishing community beside the old Brahmaputra river, Mymensingh, Bangladesh. Asian Fish Sci 15:371–386.

- Rana, M. S., Uddin, N., Bashir, M. S., Das, S. S., Islam, M. S., & Sikder, N. F. (2023). Effect of Stereospermum personatum, Senna obtusifolia and Amomumsubulatum extract in Hypoglycemia on Swiss Albino mice model. Pathfinder of Research, 1(1).

- Sen, A. (2000). Social exclusion: Concept, application and scrutiny, Social Development Paper No. 1. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Sunny, A. R., Hoque, J., Shadhin, R. H., Islam, M. S., Hamid, M. A., & Hussain, M. 2023. Exploring the Socioeconomic Landscape of Dependent Communities in Hakaluki Haor. Pathfinder of Research. 1 (1), 37-46.

- Sunny, A. R., Mithun, M. H., Prodhan, S. H., Ashrafuzzaman, M., Rahman, S. M. A., Billah, M. M., ... & Hossain, M. M. (2021a). Fisheries in the context of attaining Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Bangladesh: COVID-19 impacts and future prospects. Sustainability, 13(17), 9912.

- Sunny, A. R., Reza, M. J., Chowdhury, M. A., Hassan, M. N., Baten, M. A., Hasan, M. R., ... & Hossain, M. M. (2020). Biodiversity assemblages and conservation necessities of ecologically sensitive natural wetlands of north-eastern Bangladesh. Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences (IJMS), 49(01), 135-148.

- Sunny, A. R., Sazzad, S. A., Prodhan, S. H., Ashrafuzzaman, M., Datta, G. C., Sarker, A. K., ... & Mithun, M. H. (2021b). Assessing impacts of COVID-19 on aquatic food system and small-scale fisheries in Bangladesh. Marine policy, 126, 104422.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).