Submitted:

15 July 2024

Posted:

15 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

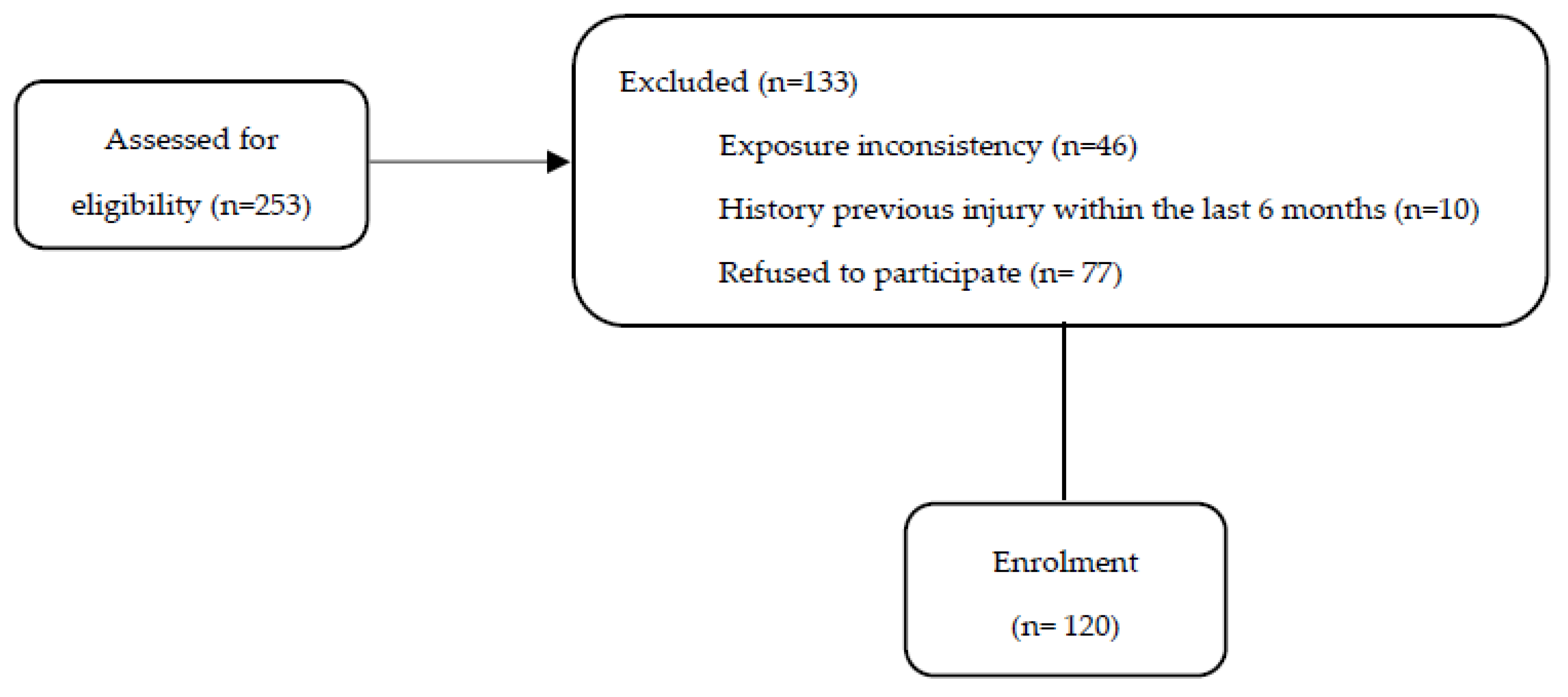

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection and Injury Data Registation

2.3. Testing Protocol

2.4. Injury Data Registration

2.5. Statistical Analysis

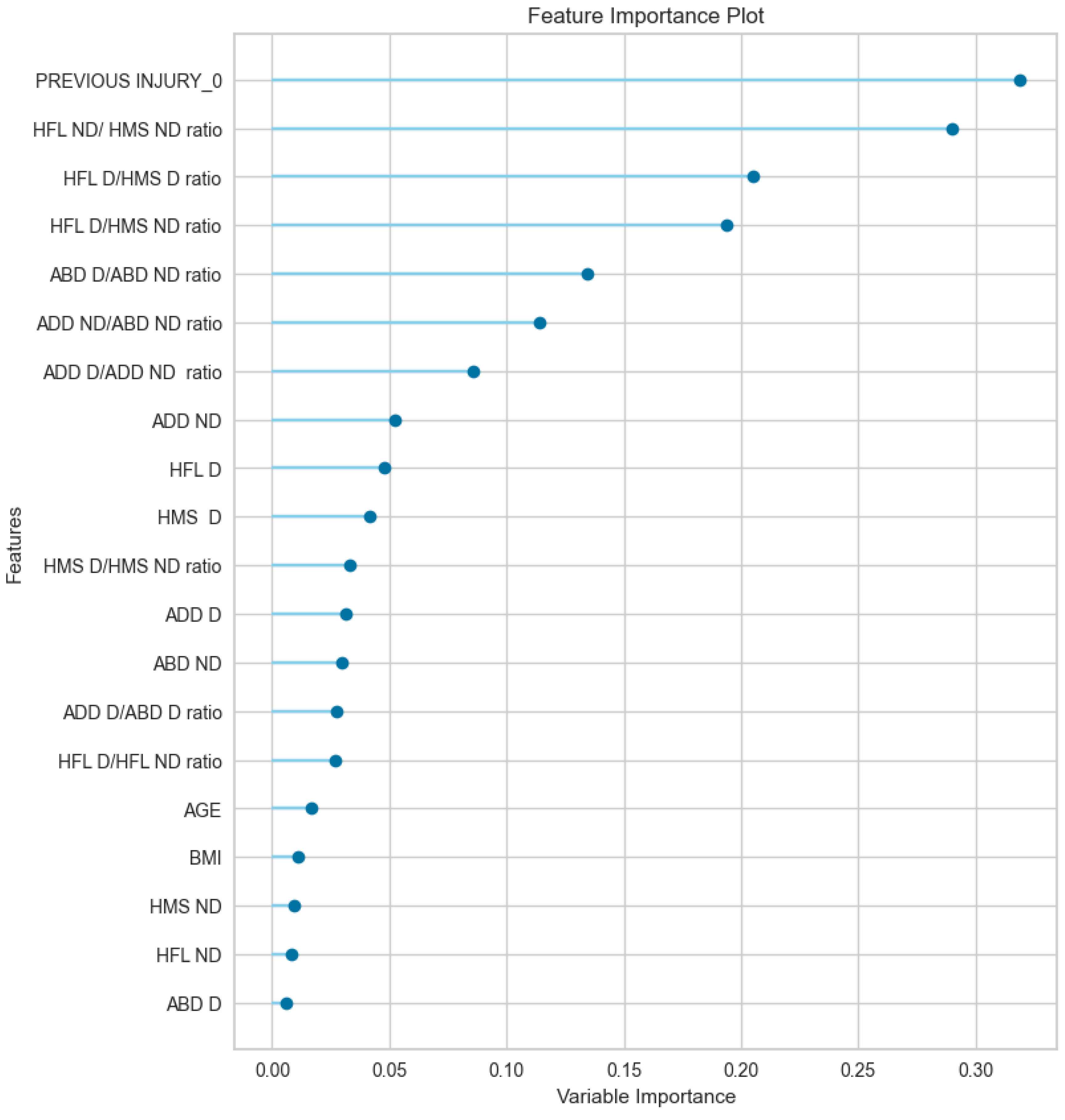

2.6. Development of the k-NN Model

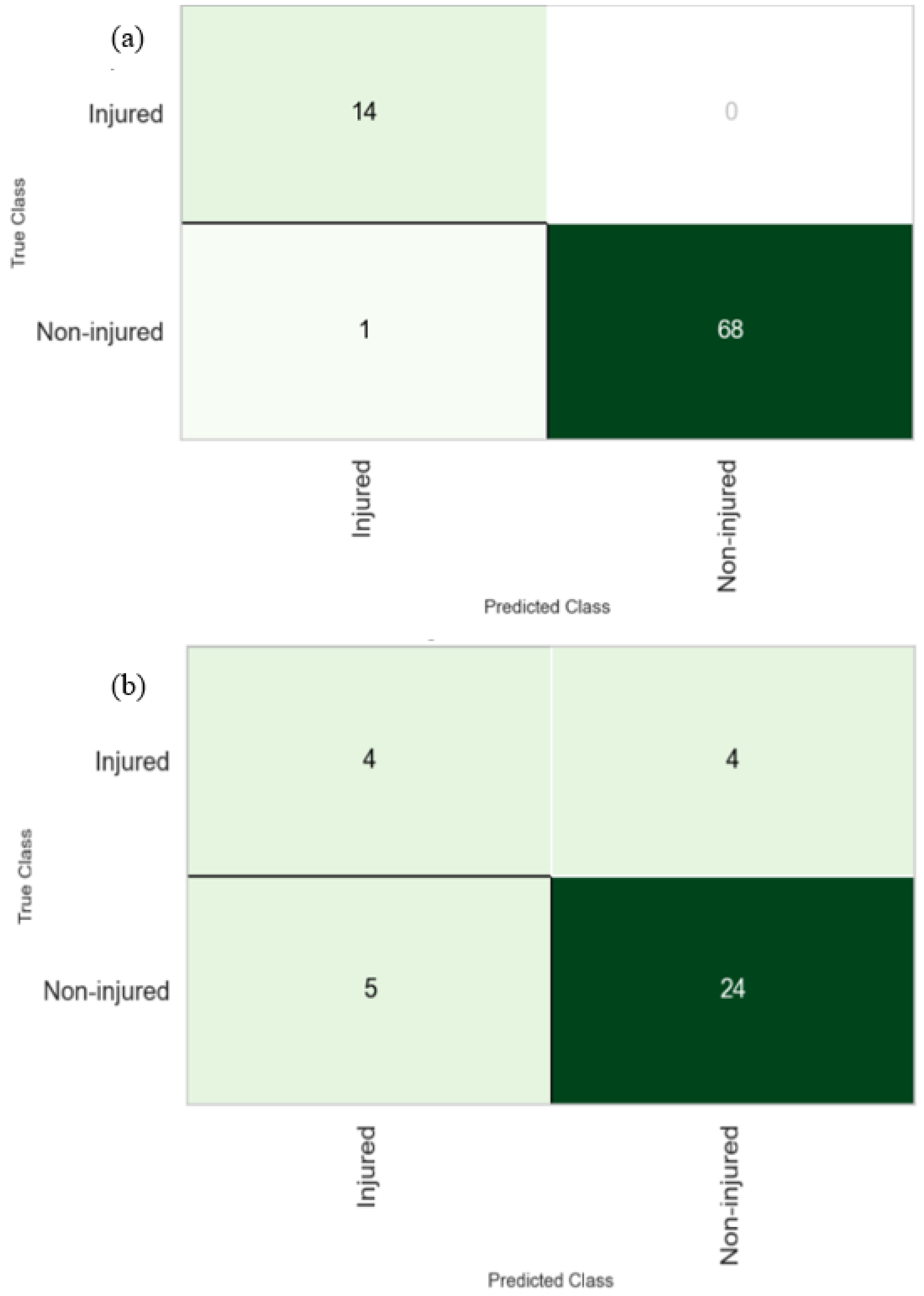

2.7. Model Evaluation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whittaker, J.L.; Small, C.; Maffey, L.; A Emery, C. Risk factors for groin injury in sport: an updated systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engebretsen, A.H.; Myklebust, G.; Holme, I.; Engebretsen, L.; Bahr, R. Intrinsic Risk Factors for Groin Injuries among Male Soccer Players. Am. J. Sports Med. 2010, 38, 2051–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serner, A.; Mosler, A.B.; Tol, J.L.; Bahr, R.; Weir, A. Mechanisms of acute adductor longus injuries in male football players: a systematic visual video analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 53, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Valenciano, A.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Garcia-Gomez, J.A.; Vera-Garcia, F.J.; De Ste Croix, M.; Myer, G.D.; Ayala, F. Epidemiology of injuries in professional football: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 54, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kekelekis, A.; Kounali, Z.; Kofotolis, N.; Clemente, F.M.; Kellis, E. Epidemiology of Injuries in Amateur Male Soccer Players: A Prospective One-Year Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosler, A.B.; Weir, A.; Eirale, C.; Farooq, A.; Thorborg, K.; Whiteley, R.J.; Hӧlmich, P.; Crossley, K.M. Epidemiology of time loss groin injuries in a men’s professional football league: a 2-year prospective study of 17 clubs and 606 players. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 52, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhout, R.; Tak, I.; van Beijsterveldt, A.-M.; Ricken, M.; Weir, A.; Barendrecht, M.; Kerkhoffs, G.; Stubbe, J. Risk Factors for Groin Injury and Groin Symptoms in Elite-Level Soccer Players: A Cohort Study in the Dutch Professional Leagues. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018, 48, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Pérez, V.; Travassos, B.; Calado, A.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Del Coso, J.; Mendez-Villanueva, A. Adductor squeeze test and groin injuries in elite football players: A prospective study. Phys. Ther. Sport 2019, 37, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, M.N.; Williams, M.; Jackson, J.; Williams, K.L.; Timmins, R.G.; Pizzari, T. Preseason Hip/Groin Strength and HAGOS Scores Are Associated With Subsequent Injury in Professional Male Soccer Players. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2020, 50, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, G.; Šarabon, N.; Pausic, J.; Hadžić, V. Adductor Muscles Strength and Strength Asymmetry as Risk Factors for Groin Injuries among Professional Soccer Players: A Prospective Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhaj, K.; Meftah, S.; Mahir, L.; Lmidmani, F.; Elfatimi, A. Isokinetic imbalance of adductor–abductor hip muscles in professional soccer players with chronic adductor-related groin pain. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2016, 16, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoffl, J.; Dooley, K.; Miller, P.; Miller, J.; Snodgrass, S.J. Factors Associated with Hip and Groin Pain in Elite Youth Football Players: A Cohort Study. Sports Med. - Open 2021, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, T.F.; Nicholas, S.J.; Campbell, R.J.; McHugh, M.P. The Association of Hip Strength and Flexibility with the Incidence of Adductor Muscle Strains in Professional Ice Hockey Players. Am. J. Sports Med. 2001, 29, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claudino, J.G.; de Oliveira Capanema, D.; De Souza, T.V.; Serrão, J.C.; Pereira, A.C.M.; Nassis, G.P. Current Approaches to the Use of Artificial Intelligence for Injury Risk Assessment and Performance Prediction in Team Sports: a Systematic Review. Sports Med. - Open 2019, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico-González, M.; Pino-Ortega, J.; Méndez, A.; Clemente, F.; Baca, A. Machine learning application in soccer: a systematic review. Biol. Sport 2023, 40, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, G.S.; Moons, K.G.M. Reporting of artificial intelligence prediction models. Lancet 2019, 393, 1577–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Valenciano, A.; Ayala, F.; Puerta, J.M.; Croix, M.B.A.D.S.; Vera-Garcia, F.J.; Hernández-Sánchez, S.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Myer, G.D. A Preventive Model for Muscle Injuries. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, F.; López-Valenciano, A.; Martín, J.A.G.; Croix, M.D.S.; Vera-Garcia, F.J.; García-Vaquero, M.D.P.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Myer, G.D. A Preventive Model for Hamstring Injuries in Professional Soccer: Learning Algorithms. Int. J. Sports Med. 2019, 40, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rommers, N.; Rössler, R.; Verhagen, E.; Vandecasteele, F.; Verstockt, S.; Vaeyens, R.; Lenoir, M.; D’hondt, E.; Witvrouw, E. A Machine Learning Approach to Assess Injury Risk in Elite Youth Football Players. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 1745–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, B.C.; Wright, A.L.; Haeberle, H.S.; Karnuta, J.M.; Schickendantz, M.S.; Makhni, E.C.; Nwachukwu, B.U.; Williams, R.J.; Ramkumar, P.N. Machine Learning Outperforms Logistic Regression Analysis to Predict Next-Season NHL Player Injury: An Analysis of 2322 Players From 2007 to 2017. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.L.; Ayala, F.; Croix, M.B.D.S.; Lloyd, R.S.; Myer, G.D.; Read, P.J. Using machine learning to improve our understanding of injury risk and prediction in elite male youth football players. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 1044–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruddy, J.D.; Cormack, S.J.; Whiteley, R.; Williams, M.D.; Timmins, R.G.; Opar, D.A. Modeling the Risk of Team Sport Injuries: A Narrative Review of Different Statistical Approaches. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauhiainen, S.; Kauppi, J.-P.; Krosshaug, T.; Bahr, R.; Bartsch, J.; Äyrämö, S. Predicting ACL Injury Using Machine Learning on Data From an Extensive Screening Test Battery of 880 Female Elite Athletes. Am. J. Sports Med. 2022, 50, 2917–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, P.-L.; Chaouachi, A.; Chamari, K.; Dellal, A.; Wisloff, U. Effect of Preseason Concurrent Muscular Strength and High-Intensity Interval Training in Professional Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13 (Suppl. 1), 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. A. Mckay et al., “De fi ning Training and Performance Caliber : A Participant Classi fi cation Framework,” pp. 317–331, 2022.

- Nielsen, M.F.; Thorborg, K.; Krommes, K.; Thornton, K.B.; Hölmich, P.; Peñalver, J.J.; Ishøi, L. Hip adduction strength and provoked groin pain: A comparison of long-lever squeeze testing using the ForceFrame and the Copenhagen 5-Second-Squeeze test. Phys. Ther. Sport 2022, 55, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorborg, K.; Couppé, C.; Petersen, J.; Magnusson, S.P.; Hölmich, P. Eccentric hip adduction and abduction strength in elite soccer players and matched controls: a cross-sectional study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 45, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorborg, K.; Petersen, J.; Magnusson, S.P.; Hölmich, P. Clinical assessment of hip strength using a hand-held dynamometer is reliable. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reurink, G.; Goudswaard, G.J.; Moen, M.H.; Tol, J.L.; Verhaar, J.A.; Weir, A. Strength Measurements in Acute Hamstring Injuries: Intertester Reliability and Prognostic Value of Handheld Dynamometry. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 46, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, M.B.; Oliveira, C.; Ornelas, G.; Soares, T.; Souto, J.; Póvoa, A.R.; Ferreira, L.M.A.; Ricci-Vitor, A.L. Intra-Rater and Inter-Rater Reliability of the Kinvent Hand-Held Dynamometer in Young Adults. CiiEM 2023. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 12.

- N. Olds, M. N. Olds, M., McLaine, S., & Magni, “Validity and Reliability of the Kinvent Handheld Dynamometer in the Athletic Shoulder Test,” J Sport Rehabil, p. [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, H. J. G H Oosterhuis, and van H. der Ploeg J G H Oosterhuis, “The ‘make/break test’ as a diagnostic tool in functional weakness F Break-F Make x 100% F Make Encouragement Index (EI) = F with E-F without E x 100% F without E Fatigue Index (FI),” 1991.

- Sisto, S.A.; Dyson-Hudson, T. Dynamometry testing in spinal cord injury. J. Rehabilitation Res. Dev. 2007, 44, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, A.; Brukner, P.; Delahunt, E.; Ekstrand, J.; Griffin, D.; Khan, K.M.; Lovell, G.; Meyers, W.C.; Muschaweck, U.; Orchard, J.; et al. Doha agreement meeting on terminology and definitions in groin pain in athletes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, C.W.; Ekstrand, J.; Junge, A.; Andersen, T.E.; Bahr, R.; Dvorak, J.; Hägglund, M.; McCrory, P.; Meeuwisse, W.H. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2006, 16, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, R.M.; Majeed, A.A.; Taha, Z.; Abdullah, M.; Maliki, A.H.M.; Kosni, N.A. The application of Artificial Neural Network and k-Nearest Neighbour classification models in the scouting of high-performance archers from a selected fitness and motor skill performance parameters. Sci. Sports 2019, 34, e241–e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, R.M.; Majeed, A.P.P.A.; Taha, Z.; Chang, S.W.; Nasir, A.F.A.; Abdullah, M.R. A machine learning approach of predicting high potential archers by means of physical fitness indicators. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0209638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, S.G.; Zheng, Y.; Wong, W.-K. Machine learning for activity recognition: hip versus wrist data. Physiol. Meas. 2014, 35, 2183–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, Z.; Musa, R.M.; Majeed, A.P.P.A.; Abdullah, M.R.; Abdullah, M.A.; Hassan, M.H.A.; Khalil, Z. The employment of Support Vector Machine to classify high and low performance archers based on bio-physiological variables. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 342, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, A.; Targett, S.; Bere, T.; Eirale, C.; Farooq, A.; Mosler, A.B.; Tol, J.L.; Whiteley, R.; Khan, K.M.; Bahr, R. Muscle Strength Is a Poor Screening Test for Predicting Lower Extremity Injuries in Professional Male Soccer Players: A 2-Year Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2018, 46, 1481–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteve, E.; Rathleff, M.S.; Vicens-Bordas, J.; Clausen, M.B.; Hölmich, P.; Sala, L.; Thorborg, K. Preseason Adductor Squeeze Strength in 303 Spanish Male Soccer Athletes: A Cross-sectional Study. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLang, M.D.; Garrison, J.C.; Hannon, J.P.; McGovern, R.P.; Christoforetti, J.; Thorborg, K. Short and long lever adductor squeeze strength values in 100 elite youth soccer players: Does age and previous groin pain matter? Phys. Ther. Sport 2020, 46, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, B.X.W.; Kovacs, F.M.; Rügamer, D.; Royuela, A. Machine learning versus logistic regression for prognostic modelling in individuals with non-specific neck pain. Eur. Spine J. 2022, 31, 2082–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré, T.; Potthast, W. Are sprint accelerations related to groin injuries? A biomechanical analysis of adolescent soccer players. Sports Biomech. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupré, T.; Tryba, J.; Potthast, W. Muscle activity of cutting manoeuvres and soccer inside passing suggests an increased groin injury risk during these movements. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Pérez, V.; Peñaranda, M.; Soler, A.; López-Samanes; Aagaard, P.; Del Coso, J. Effects of Whole-Season Training and Match-Play on Hip Adductor and Abductor Muscle Strength in Soccer Players: A Pilot Study. Sports Heal. A Multidiscip. Approach 2021, 14, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupré, T.; Funken, J.; Müller, R.; Mortensen, K.R.L.; Lysdal, F.G.; Braun, M.; Krahl, H.; Potthast, W. Does inside passing contribute to the high incidence of groin injuries in soccer? A biomechanical analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 1827–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charnock, B.L.; Lewis, C.L.; Garrett, W.E.; Queen, R.M. Adductor longus mechanics during the maximal effort soccer kick. Sports Biomech. 2009, 8, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, C.A.; Meeuwisse, W.H. Risk factors for groin injuries in hockey. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 1423–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellis, E.; Katis, A. Biomechanical characteristics and determinants of instep soccer kick. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2007, 6, 154–165. [Google Scholar]

| Mechanism of groin injury | N |

|---|---|

| Change of direction (CoD) | 12 |

| Acceleration | 4 |

| Stretching | 3 |

| Kicking | 2 |

| inside pass | 2 |

| Decceleration | 2 |

| Total | 25 |

| Accuracy | AUC | Recall | Prec. | F1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.556 | 0.425 | 0.609 | 0.806 | 0.688 |

| Std | 0.131 | 0.278 | 0.941 | 0.108 | 0.197 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | B | SE | Z | p | Odds ratio | Lower | Upper | |

| Intercept | 2.5628 | 1.744 | 1.4697 | 0.142 | 12.972 | 0.4253 | 395.618 | |

| History | -1.0997 | 0.58 | -1.8952 | 0.050* | 0.333 | 0.1068 | 1.038 | |

| HFL ND/ HMS ND ratio | 0.1479 | 1.703 | 0.0869 | 0.931 | 1.159 | 0.0412 | 32.626 | |

| HFL D/HMS D ratio | 0.0499 | 1.354 | 0.0368 | 0.971 | 1.051 | 0.0739 | 14.943 | |

| HFL D/HMS ND ratio | 1.1717 | 1.55 | 0.7558 | 0.45 | 3.228 | 0.1546 | 67.366 | |

| ABD D/ABD ND ratio | 0.4482 | 1.113 | 0.4028 | 0.687 | 1.566 | 0.1768 | 13.862 | |

| ADD ND/ABD ND ratio | -1.4362 | 0.448 | -3.2047 | 0.001* | 0.238 | 0.0988 | 0.572 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).