Introduction

Cancer accounts for the second leading cause of death among non-communicable diseases (NCD) [

1], with 20 million new cases in year 2022 one half of cases(49.2%) reported and deaths(56.1%)worldwide occurring in Asia, where globally breast cancer accounted for 2.3 million of the cases after lung cancer and mortality of 665,684. [

2,

3,

4,

5]. According to GLOBOCAN Pakistan 2022, a total of 229,488,996 individuals suffered from cancer, with 185,748 new cases and 118,631 deaths reported. Among these cases, breast cancer ranked first with 30,682 new cases (16.5%) and the highest mortality of 15,552 (13.1%), emerging as the most prevalent and significant contributor, surpassing lung cancer [

6]. Breast cancer annually affects approximately 2.3 million women, with 675 million deaths with a pronounced surge observed in South Asia, intensifying the region's NCD burden. [

7]

While the incidence of breast cancer in Asia remains lower compared to Western countries, its proportional contribution to the global burden of breast cancer is swiftly escalating in the modern era, expected to increase up to 2 million by 2030 [

8]. In South Asia, particularly in Pakistan, the escalating incidence of non-communicable diseases has thrust breast cancer to the forefront of women's mortality, with one in every nine women facing a lifetime risk of diagnosis [

4,

9]. Pakistan exhibits one of the highest age-standardized incidence rates of breast cancer among Asian nations. A comprehensive analysis of past and projected trends in age-specific breast cancer incidence among women in Karachi reveals a notable increase in breast cancer rates among postmenopausal women, particularly those aged 55 to 59. Simultaneously, a steady rise in incidence is projected among the youngest age group of women (15–29 years) in Karachi [

10,

11]. Unfortunately, the country also witnesses a higher incidence of breast cancer-related deaths, largely due to delayed diagnosis and referral to appropriate healthcare facilities [

10].

The WHO defines two strategies for cancer early detection: early diagnosis, which recognizes symptomatic cancer at an early stage, and screening, which identifies asymptomatic disease [

12]. Early-stage diagnosis significantly improves prognosis, while delays and lack of treatment availability contribute to advanced stages and low survival rates of breast cancer [

13]. Awareness of the disease plays a crucial role in early diagnosis, helping individuals avoid associated risk factors and adhere to screening guidelines, facilitating early detection. The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends clinical breast examinations by a healthcare provider every three years for women aged 20–30 and annually for women aged 40 and above [

14]. A study at Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences evaluated breast cancer Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) among 1000 women. Results showed that while 75% of women recognized the disease, only 32% understood the disease process and prevention methods. Only 19.6% had undergone mammography, and 78.8% did not know the correct age for screening. Awareness of breast self-examination (BSE) and clinical breast examination (CBE) was also low, with only 28.7% knowing about BSE and 30.3% aware of CBE. The findings highlight the need for improved educational programs on breast cancer prevention and screening in Pakistan. [

15]

The BHGI Summit developed a universal patient pathway for breast cancer management, focusing on timely detection, diagnosis, and treatment across all resource settings. Despite resource challenges, low-income countries must prioritize equitable access to high-quality breast cancer care, using frameworks set by the WHO, BHGI, and the ACR [

12]. Despite significant advances, less than half of breast cancers are screen-detected, underscoring the need for improved early diagnostic strategies, particularly for patients under 40-45 years. Early diagnosis, even without mammographic screening, can downstage invasive cancer and improve outcomes. The ACR provides comprehensive breast cancer guidelines encompassing screening, diagnosis, and tailored care plans [

16]. They advocate regular mammograms for average-risk women starting at age 40, while emphasizing personalized screening for higher-risk individuals. This includes breast MRI for those with genetic predispositions or early chest radiation exposure. Women with BRCA mutations should start MRI surveillance at ages 25 to 30 and can delay mammograms until age 40 if annual MRI is performed. Women diagnosed with breast cancer before age 50 or those with dense breasts should have annual supplemental MRI, and those with personal histories or atypia should consider MRI if other risk factors are present. Genetic predisposition, accounting for 5% to 10% of breast cancers, significantly increases risk, especially in BRCA mutation carriers [

17,

18,

19]

Screening mammography can reduce mortality by over 40%, but higher-risk women often have dense breasts and more aggressive tumors, necessitating additional screening methods. The Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS®), developed by the American College of Radiology (ACR), standardizes breast pathology reporting from mammograms, ultrasounds also known as double reporting and MRIs to ensure consistent communication between radiologists and physicians. The 5th edition classifies breast density into (A) almost entirely fatty, (B) scattered areas of fibroglandular density, (C) heterogeneously dense (possibly obscuring small masses), and (D) extremely dense (reducing mammography sensitivity). BI-RADS assessment categories are: 0 (incomplete, needs further imaging), 1 (negative), 2 (benign), 3 (probably benign, <2% malignancy risk), 4 (suspicious, 2%-95% malignancy risk, subdivided into 4A, 4B, and 4C), 5 (highly suggestive of malignancy, >95% risk), and 6 (confirmed malignancy). This system aids in risk stratification and management recommendations. [

17,

19]

In Pakistan, breast cancer incidence and mortality rates are rising rapidly in resource-limited areas, due to a lack of awareness and screening. Screening programs and clinical services are neglected due to insufficient equipment, funds, and quality standards, with breast cancer occurring at a younger age compared to affluent nations [

20]. Financial barriers further hinder access to screening, diagnosis, and treatment [

19]. This highlights the need for improved screening facilities and financial support to ensure timely detection and treatment in resource-limited settings [

4,

20,

21].

Published literature confirms a strong correlation between increasing age and breast cancer incidence, advocating for regular mammography screening. Factors such as family history, reproductive and estrogen-related factors, and modern lifestyles with excessive alcohol consumption significantly contribute to breast cancer development. Women with a family history of breast cancer are more prone to developing the disease. Reproductive factors like early menarche, late menopause, late age at first pregnancy, and low parity also increase breast cancer risk [

11,

14].

According to the National Cancer Registry (NCR) of Pakistan report for 2015 to 2019, 21% of all cancers reported were breast cancer among both the male and female population above the age of 40 years. This pioneering effort by the NCR, uniting all cancer registries and datasets across Pakistan under the NIH, Islamabad, and led by the PHRC and directed by the Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination, aims to comprehensively analyze cancer patterns, compile patient registries to be shared within hospitals at both the provincial and federal levels, make cancer a notifiable disease, and employ frameworks and set policies to tackle this looming epidemic [

22].

Until a few years ago, no public breast cancer facility existed in the Islamabad Capital Territory of Pakistan. However, with the establishment of the Federal Breast Screening Center (FBSC), Islamabad, rigorous awareness campaigns and screenings for women aged above 40 were initiated, alongside interventions employing a six-tiered approach to strengthen the healthcare system.

According to the pilot study, the FBSC provided services to patients from 2015 to 2019, witnessing an annual increase in the number of women seeking screening, categorized based on their BIRADS classification. [

23]

Breast cancer stands as a leading cause of cancer mortality in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), primarily due to delayed presentation and limited access to healthcare. While survival rates vary globally, Western Europe boasts higher rates owing to superior screening and treatment facilities. Over the past four decades, heightened awareness and timely mammography in affluent nations have significantly reduced mortality rates [

4,

9,

24].

Late diagnosis of breast cancer severely restricts treatment options and outcomes. Key factors contributing to delayed diagnosis, as observed in low-income African women and replicated in Pakistan, include low socioeconomic status and education, limited awareness of early detection methods, symptom dismissal, fear of disease and treatment, reliance on traditional remedies, financial constraints, and restricted healthcare access due to distance or lack of transportation. [

4,

21].

In LMICs, breast cancer often manifests as locally advanced breast cancer (LABC), comprising 40-60% of cases at diagnosis. Clinical stage at diagnosis significantly impacts survival rates [

25]. Evolving risk factors and disparities in accessing early detection and treatment contribute to this trend. Factors such as age, race, ethnicity, menarche history, breast characteristics, reproductive patterns, hormone use, breastfeeding history, dietary habits, and lifestyle choices play significant roles [

26].

Socioeconomic status notably influences a patient's ability to address these factors and access diagnostic facilities promptly. There exists a clear association between socio-demographic and clinical indicators and delays in reaching diagnostic centers [

27,

28] Low-income countries like Pakistan serve as compelling settings to observe these dynamics. This study utilized data from 2020 to 2023 to specifically examine how variables such as age, race, breast composition, breastfeeding history, socioeconomic status, and education status contributed to the escalating incidence of breast cancer in Pakistan. The investigation also scrutinized the subsequent management steps patients received post-diagnosis, aligning with the guidelines set by the American College of Radiology (ACR). The focus was particularly on understanding the efficacy of these measures within advanced facilities like the Federal Breast Screening Center.

In Pakistan, implementing breast cancer screening and intervention guidelines from both the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the World Health Organization is underway. However, due to diverse ethnicities, evolving lifestyles, limited local data, and rising incidence, simply increasing health financing isn't enough. It's crucial to allocate funds towards strengthening the healthcare system, focusing on how effectively resources translate into improved access to quality care and developing tailored guidelines for the Pakistani population. [

29] While it may be challenging for many nations to adopt effective breast cancer screening and treatment policies from high-income countries, upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) have experienced increased rates of early detection and improved survival through combined efforts in early detection and adjuvant systemic therapy. [

25] Guidelines for breast cancer screening and management serve as fundamental pillars in combating this disease, streamlining processes, and ensuring standardized, evidence-based approaches crucial for early detection and intervention. The Federal Breast Screening Centre, Islamabad stands as a beacon, championing adherence to such guidelines, offering accessible and quality breast cancer screening services in the region.

The initial data recorded at the Federal Breast Screening Centre, Islamabad from 2015 to 2019, along with four additional years of data spanning from 2020 to 2023, provides a unique opportunity to evaluate Pakistan's preparedness for implementing a national guideline on breast cancer screening and management. This research also aims to utilize insights derived from four years of data analysis to examine various demographic characteristics, including age, ethnicity, education status, socio-economic factors, breastfeeding history, breast density, and family medical history, and their association with breast cancer diagnosis and subsequent management. The study seeks to determine whether the accumulated data and experiences support the development of a comprehensive national guideline aimed at improving screening, management, and treatment strategies, not only in Islamabad but also for the wider South Asian population.

Results

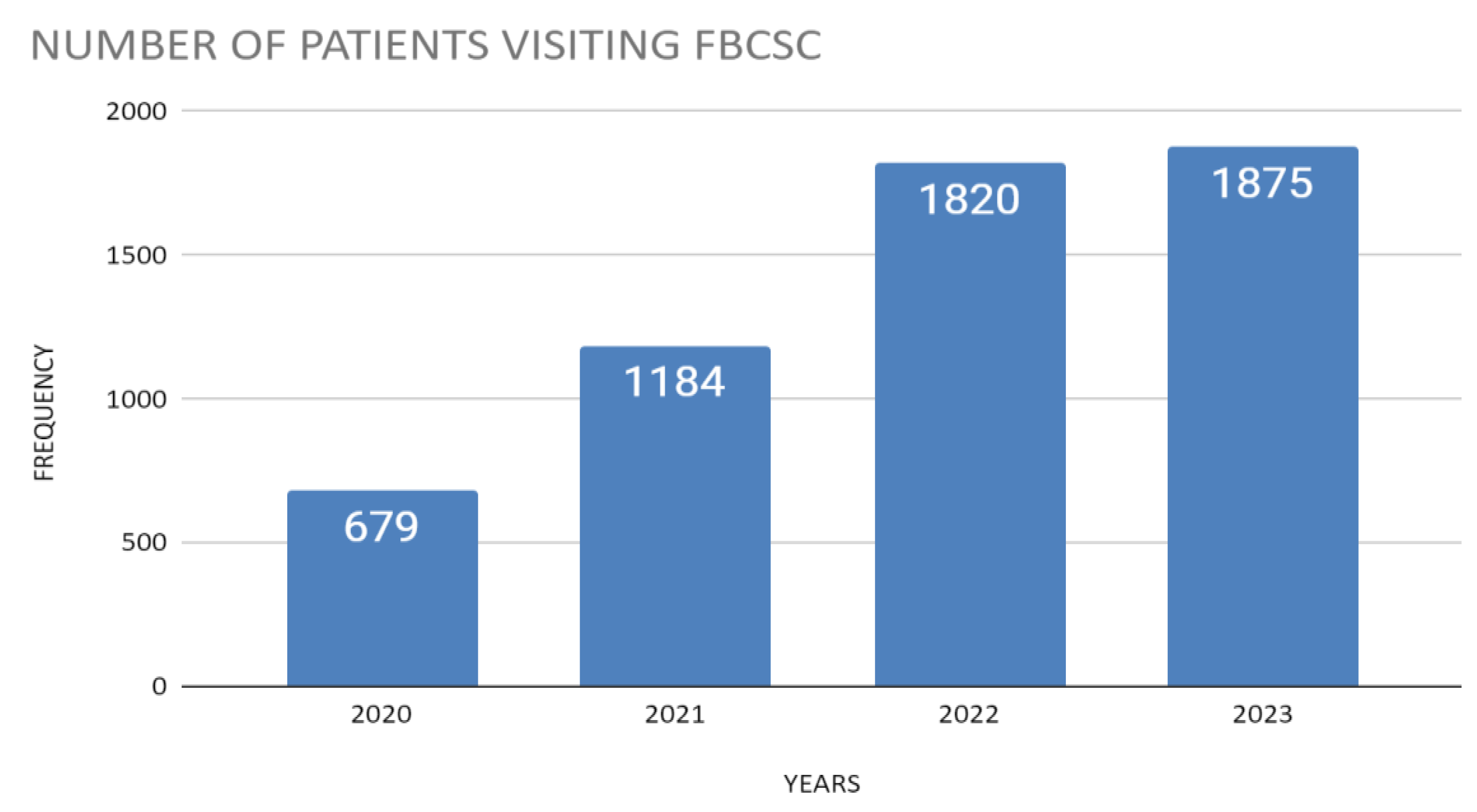

During 2015-2019, a total of 4,337 patients visited the Female Breast Screening Center (FBSC). From 2020 to 2023, the center saw 5,580 patients (

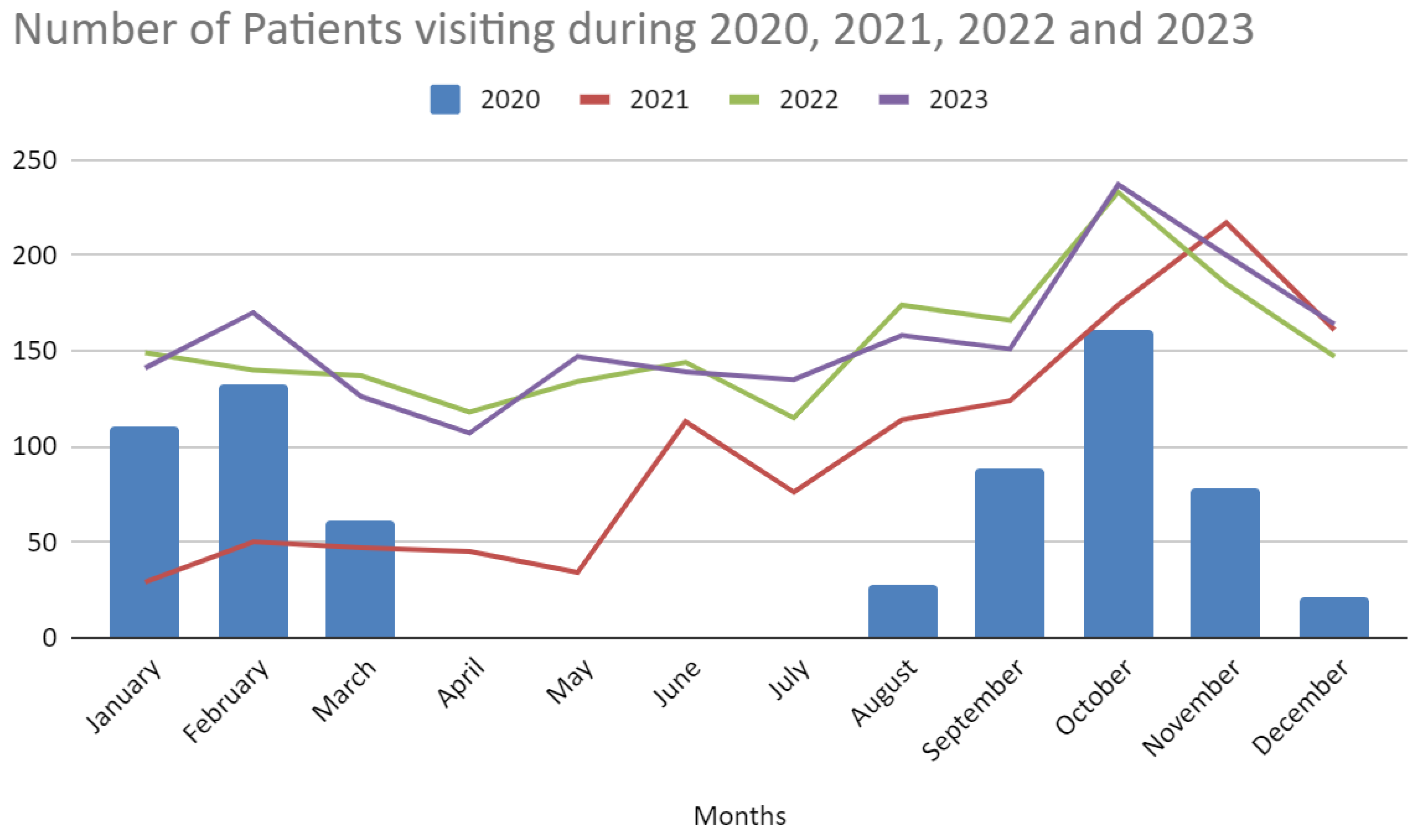

Figure 1.1) In 2020, the COVID-19 lockdown led to suspended operations from April to July, resulting in only 679 (12.2%) women presenting for screening that year. January and February had the highest numbers, 110(16.2%) and 132(19.4%) of the annual total, respectively. Visits dropped to zero from April to July but gradually increased, peaking in October at161 (23.7%).

In 2021, a notable shift occurred with 1,184 (21.2%) women participating. The year began with lower numbers in January and February, representing 29(2.5%) and 50(4.2%) of the annual total, respectively. Summer months, particularly June and August, saw increased activity, with 113(9.5%) and 114(9.6%) of the year’s total. The highest visitation occurred in November, comprising 217(18.3%) of the annual total.

In 2022, participation further increased to 1,842 (33.0%) women. Monthly visits were more evenly distributed, with January, February, and March accounting for 149(8.1%), 140(7.6%), and 137(7.4%) of the annual total, respectively. The autumn months experienced the highest visitation rates, particularly October with 233(12.6%) of the total visits, followed by November with 185(10.0%).

By the end of 2023, participation reached 1,875 (33.6%) women. The highest visitation occurred in October, comprising 237(12.6%) of the annual total. February and November also saw significant numbers, accounting for 170(9.1%) and 200(10.7%), respectively. This steady distribution of patient visits across the months suggests a stabilized flow of patients to the center. Overall, the data indicate a trend of increasing patient visits to the FBSC from 2020 to 2023, highlighting the center's critical role in breast cancer care and recovery post-lockdown, depicted by

Figure 1.2.

Table 1.1 describes the above data and revealing that the mean age of patients attending screenings from 2020 to 2023 was 48.50 ± 9.55 years, with the most common age group being 41-45 years 1,364 (24.4%), followed by 46-50 years 1,008 (18.1%). The ethnicity with the highest frequency was Punjabi 4,647 (83.3%), followed by Pukhtoon patients 417 (7.5%) and Kashmiri patients 243 (4.4%). When observing marital status, the majority of the patients were married 5,435 (97.4%), with less than half of the marriages being consanguineous 2,300 (41.2%). Most of the patients had a positive breastfeeding history 4,826 (86.5%). Pakistan is a developing country with most of its population living under the poverty line, so the socio-economic status of the patients was lower 1,779 (31.9%), middle 3,726 (66.8%), and upper 75 (1.3%). Most of the patients were uneducated 2,079 (37.3%), followed by Matric 832 (14.9%), and primary 524 (9.4%).

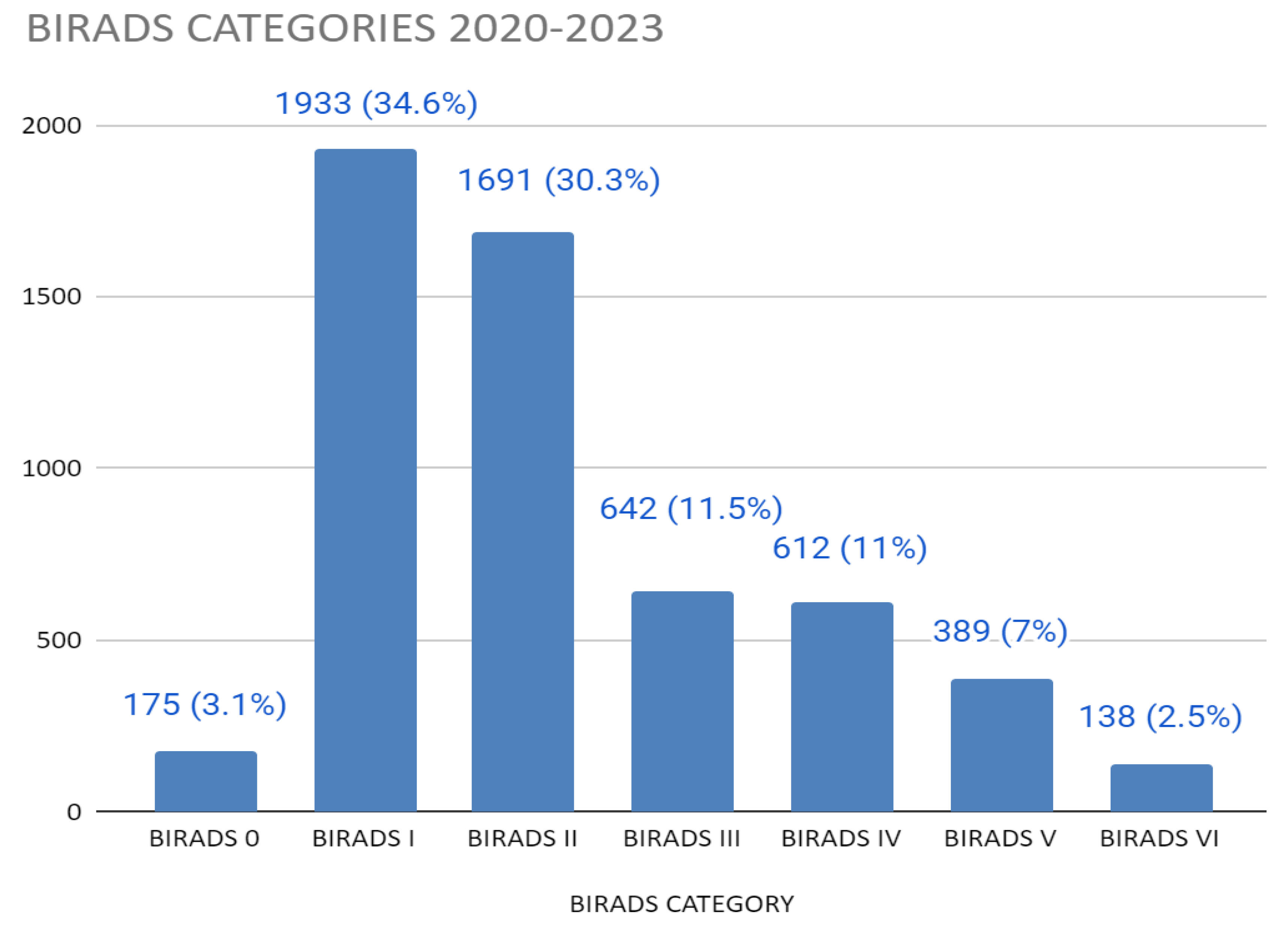

The BIRADS category with the highest frequency was BIRADS I 1,933 (34.6%), followed by BIRADS II 1,691 (30.3%) (

Table 1.2). Those screened for suspicion of malignancy included BIRADS V 389 (7.0%) and biopsy-proven breast cancer BIRADS VI 138 (2.5%). When observing breast densities, Type B breast density was the most common, found in 2535 (49.97%) of right breasts and 2510 (49.69%) of left breasts. Type A density followed with 1021 (20.13%) in right breasts and 1021 (20.18%) in left breasts, while Type C and Type D densities were less prevalent. A minimal number of patients had implants or underwent modified radical mastectomy (MRM). Mammography was not performed in 5 cases (0.10%) right, 4 cases (0.08%) left likely because the prescribing doctor requested mammography only for the affected breast. Regarding the trend in the number of visits for breast screening, most of the patients were first-time visitors 4,648 (83.3%), followed by second-time visitors 821 (14.7%), while third-time visitors made up 93 (1.7%) of the total. When observing the signs and symptoms, the patients presented with pain in the breasts 3,598 (64.5%), mass in the breasts 2,648 (47.5%), and nipple discharge 413 (7.4%) (

Figure 1.3).

Breast cancer was diagnosed based on biopsy reports, where invasive breast cancer accounted for 580 patients (10.4%), followed by cases suspicious for malignancy, 174 patients (3.1%), and benign breast disease, 60 patients, (1.1%). Hence, the prevalence rate of invasive breast cancer during these four years was 10.4%. Among those who reported receiving treatment for breast cancer, 149 (2.7%) received chemotherapy, 241 (4.3%) received both chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and 2 (0.0%) received radiotherapy alone. Among those with a surgical history, 271 (4.9%) had a biopsy, and 136 (2.4%) had an FNAC. Additionally, 174 (3.1%) underwent left MRM, 152 (2.7%) had a right MRM, and 167 (3.0%) had lumpectomies. Patients with a positive previous history of breast cancer numbered 564, making up 10.1%, while those with a history of other cancers were 21 patients (0.4%). A notable portion, 859 (15.4%), of patients reported a positive family history of breast cancer. Among those with reported history of breast cancer among familial relations, the most common relations included mother 202 (3.6%), sister 208 (3.7%), and maternal aunt 159 (2.8%).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate breast cancer screening practices at a well-established center in Islamabad, Pakistan, and to explore trends in breast health services and breast cancer prevalence. The findings revealed variations in patient visits based on demographic factors like age, education, marital status, ethnicity, and family history of breast cancer.

The study shows significant fluctuations in case numbers from 2020 to 2023, with cases starting at 12.2% in 2020, rising to 21.2% in 2021, and reaching 33.0% in 2022, peaking at 33.6% in 2023. The standard deviation of 0.1035 indicates moderate variability in annual case distribution. Monthly visitor data from 2020 to 2023 at the Female Breast Screening Center (FBSC) showed a mean of 116.0 visitors with a high standard deviation of 53.0, reflecting the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to a significant decline in 2020. This decline is consistent with other studies showing reduced screening rates during the pandemic. [

30] However, visitor numbers increased from 2021, reaching 33.6% of pre-pandemic levels by 2023, reflecting a global trend of recovery in screening activities as services resumed and public awareness efforts intensified. [

31]

The demographic analysis of patients from 2020 to 2023 showed a mean age of 48.50 ± 9.55 years, with the most common age groups being 41-45 years (24.4%) and 46-50 years (18.1%), indicating that middle-aged women are the most engaged in screening activities. The highest number of screenings occurred in 2023 (33.6%), while the lowest was in 2020 during the pandemic (12.2%). The overall age distribution at the Federal Breast Cancer Centre had a mean age of 41.73 years with a standard deviation of 11.98 years, reflecting a diverse patient population aged 26 to 75 years. This variation highlights that the Centre serves a broad age range, with a notable concentration in the 41-50 year age groups, consistent with literature showing that middle-aged women are the main participants in breast cancer screening programs due to their higher risk of the disease. [

32]

The ethnic diversity analysis at the FBSC revealed that Punjabi individuals made up 83.3% of the patient population, with smaller proportions of Pukhtoon (7.5%), Kashmiri (4.4%), Gilgiti (1.5%), and Afgani (1.9%) individuals. The high standard deviation of 1,311.0 in the number of patients across different ethnic groups indicates substantial variability, underscoring the predominance of the Punjabi population while also reflecting the presence of smaller ethnic groups. This significant variability underscores the importance of targeted outreach efforts to ensure all ethnic groups receive adequate information and support for breast cancer screening. A systematic review highlighted the multiple barriers faced by different ethnicities and low-income groups, which affect their participation in breast cancer screening [

33].

Socio-economic analysis showed that 66.8% of patients came from middle-class backgrounds, with a standard deviation of 0.012, indicating moderate variability. This finding is consistent with existing research demonstrating socio-economic disparities in breast cancer screening participation. According to a study conducted in Punjab, Pakistan exploring fears and barriers for seeking breast health services, the majority of interviewed patients were from lower socio-economic backgrounds, facing significant barriers to breast cancer treatment due to high costs and minimal government support, leading many to delay treatment and hide their pain. [

34] Additionally, the educational status analysis revealed that 37.3% of patients were uneducated, with a higher standard deviation of 0.089, reflecting a broad spectrum of educational backgrounds. This variability may influence patient outreach and education strategies, suggesting a need for targeted educational interventions to improve screening uptake among less-educated populations [

28,

35]. A study at Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences evaluated breast cancer Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) among 1000 women. Results showed that while 75% of women recognized the disease, only 32% understood the disease process and prevention methods. Only 19.6% had undergone mammography, and 78.8% did not know the correct age for screening. Awareness of breast self-examination (BSE) and clinical breast examination (CBE) was also low, with only 28.7% knowing about BSE and 30.3% aware of CBE. The findings highlight the need for improved educational programs on breast cancer prevention and screening in Pakistan. [

30]

Analysis of family history data showed that 84.6% of participants had no family history of breast cancer, with a standard deviation of 0.36, indicating moderate variability. This high percentage suggests that initial mammogram screenings are broadly utilized, including among those without known familial risk factors. Conversely, the 15.4% of patients with a family history highlights the importance of considering familial and genetic factors in breast cancer risk assessments. The predominance of patients without a family history supports the notion that mammograms serve as a crucial tool for early detection in the general population, not just those with known genetic risks.

The distribution of BIRADS categories among the study population revealed that 34.6% of patients were classified as BIRADS I (negative findings) and 30.3% as BIRADS II (benign conditions). A smaller percentage of patients were categorized as BIRADS V (7.0%) and VI (2.5%), indicating high suspicion of malignancy and known biopsy-proven malignancy, respectively. The standard deviation of 2.27 in BIRADS categories reflects a moderate variability in diagnostic outcomes, highlighting the effectiveness of mammographic screening in identifying both benign and suspicious conditions. This finding underscores the role of BIRADS categories in guiding further diagnostic and management strategies.

Exploring data on treatment and surgical histories revealed that 93.0% of patients did not receive additional treatments beyond diagnosis. The standard deviation of 0.454 indicates moderate variability in the types of treatments provided, with the majority of patients managing their conditions without further intervention. In terms of surgical history, 82.9% of patients did not undergo any surgical procedures, with a small percentage undergoing treatments such as biopsy or mastectomy. This trend reflects a preference for non-invasive management strategies for early-stage breast cancer, which aligns with findings from other studies that emphasize early detection and less aggressive treatment options.

Cancer, particularly breast cancer, poses a significant threat to public health, accounting for a substantial portion of global mortality, particularly in Asia. Breast cancer has emerged as a leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women, necessitating a robust healthcare response to mitigate its impact. [

1,

7,

9]Efforts to strengthen health systems, particularly in low-resource settings like Pakistan, are essential to address the escalating burden of non-communicable diseases, including breast cancer.

In Pakistan, the prevalence of breast cancer has been on the rise, with recent statistics highlighting its significant contribution to the overall cancer burden [

10,

15]. The study utilized data from the National Cancer Registry, revealing breast cancer's prominence among reported cases, particularly affecting individuals over 40 years old. [

10,

22] The findings underscore the urgency of bolstering health system capacities to effectively address breast cancer, aligning with broader efforts to combat non-communicable diseases. Late diagnosis remains a critical challenge, often resulting in advanced disease stages and limited treatment options [

4]. Socioeconomic factors, including education level and access to healthcare, play a crucial role in influencing breast cancer outcomes, emphasizing the importance of equitable healthcare access and awareness campaigns.

Efforts to address breast cancer in Pakistan have been multifaceted, with initiatives ranging from awareness campaigns to the establishment of specialized screening centers. The Federal Breast Screening Center in Islamabad exemplifies such efforts, providing essential screening services and interventions to mitigate the impact of breast cancer. However, challenges persist, including limited resources, diverse population demographics, and evolving risk factors. By leveraging data-driven insights and evidence-based approaches, policymakers can develop targeted interventions to improve breast cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment strategies. Collaborative efforts between healthcare providers, policymakers, and community stakeholders are essential to address the complex challenges posed by breast cancer effectively.

In conclusion, the findings from this study highlight the pressing need for comprehensive strategies to address breast cancer in Pakistan. By leveraging demographic insights and evidence-based approaches, policymakers can develop tailored interventions to improve breast cancer outcomes and reduce its burden on public health. Strengthening health systems, enhancing access to quality care, and promoting early detection initiatives are crucial steps in combating breast cancer and achieving better health outcomes for all individuals affected by this disease.