Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

15 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Literature Search and Selection

2.2. Brief description of our patient

2.3. Data Analysis

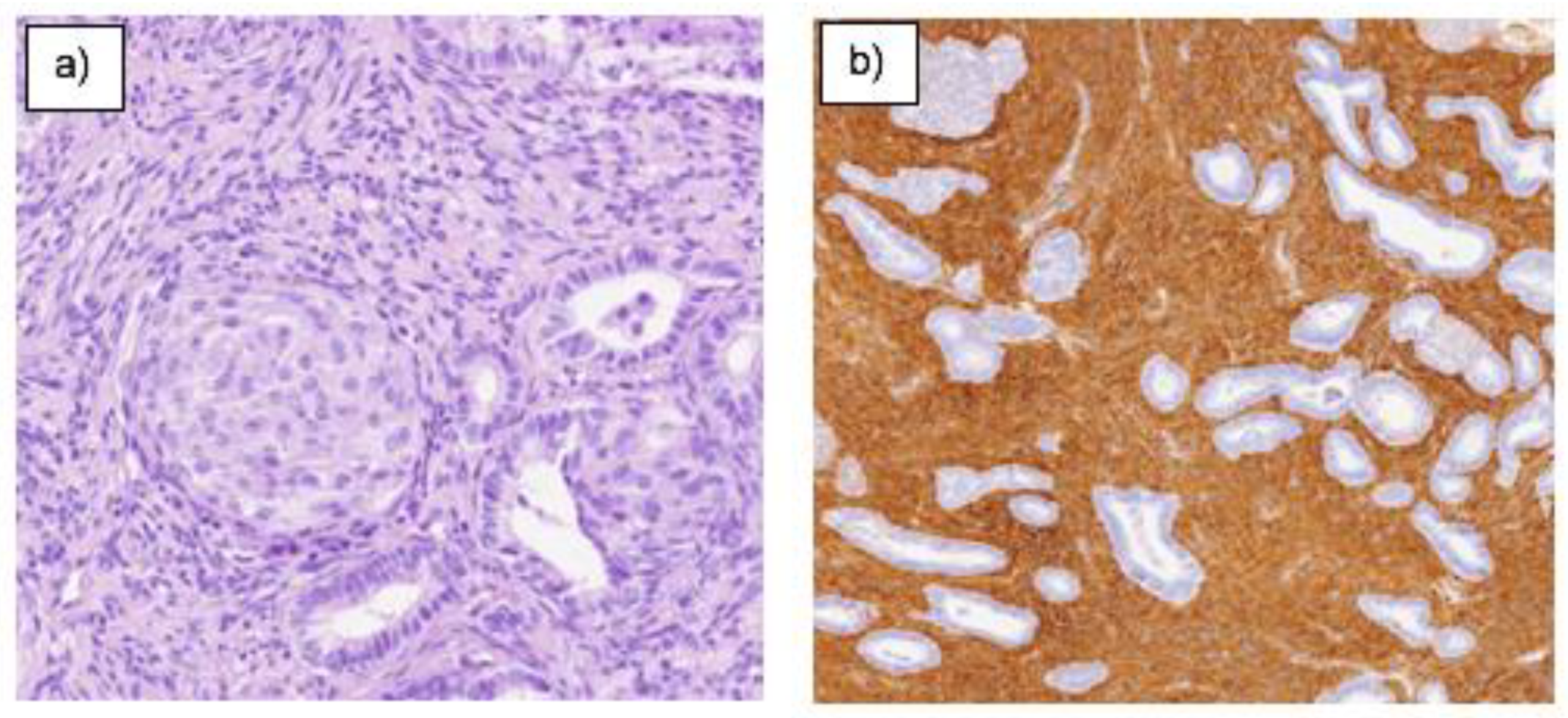

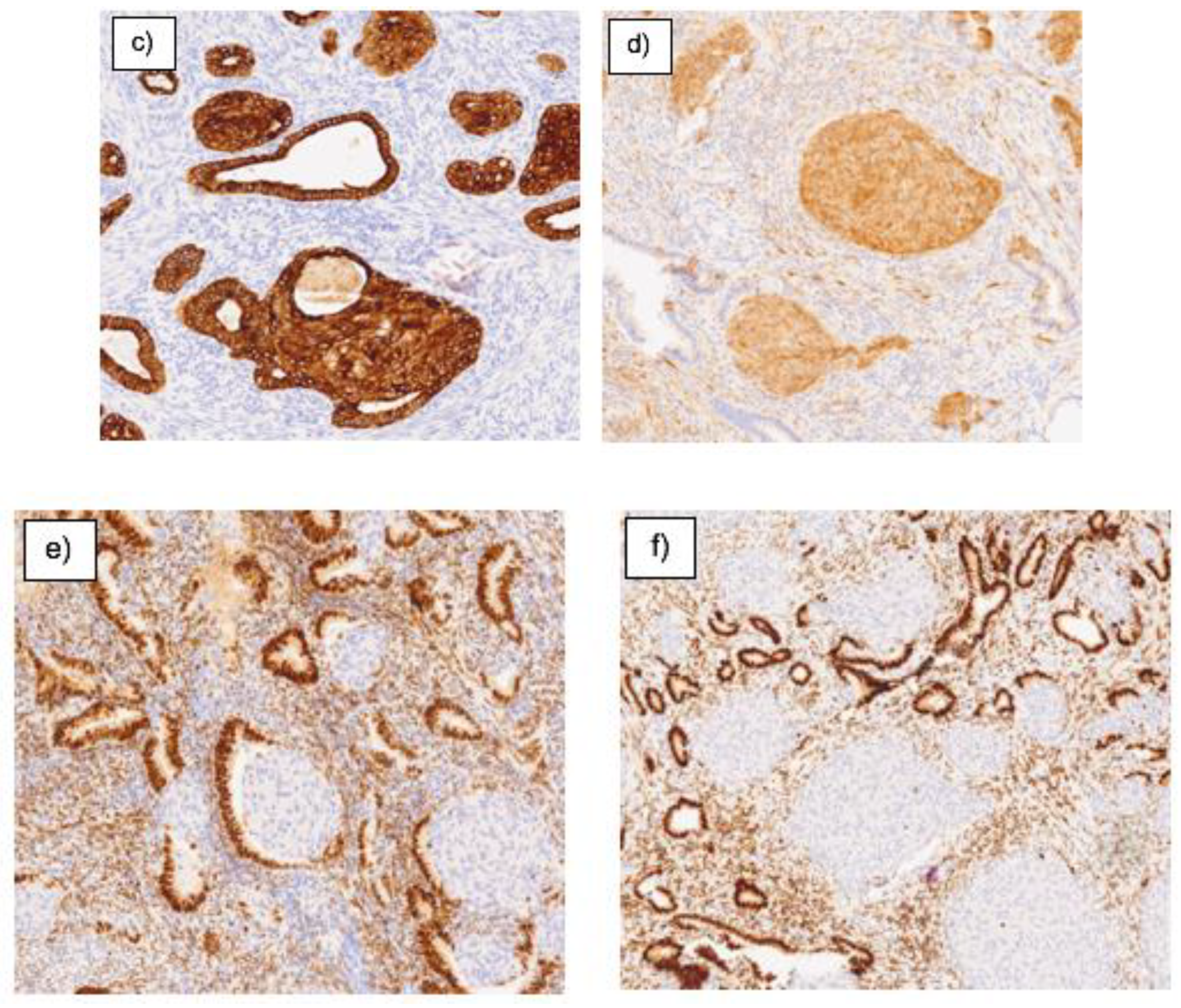

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

2.5. Molecular Biology

2.6. Meta-analysis

3. RESULTS

| GLANDULAR IHQ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Cases | B-Catenin | Ki67 | ER/PR | Pancytokeratin | PTEN+ | |

| OWN CASE | 1 | + | + | + | ||

| YUE | 99 | 2+ | + | + | ||

| TAKASHI | 7 | + | + | |||

| NEMEJCOVA | 21 | 2+ | 3+ | |||

| OTA | 6 | 3+ | ||||

| LU | 36 | + | + | |||

| TERADA | 5 | + | + | 2+ | ||

| SOSLOW | 23 | + | 3+ | |||

| ESTROMAL IHQ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | CD10- | H-caldesmon- | Desmin | Vimentin | SMA | |

| OWN CASE | 1 | + | + | |||

| YUE | 99 | - | - | 3+ | 3+ | |

| TAKASHI | 7 | - | + | |||

| LU | 36 | + | - | + | ||

| TERADA | 5 | 2+ | 2+ | 3+ | + | |

| SOSLOW | 23 | 2+ | 3+ | |||

| KIHARA | 12 | 2+ | + | 2+ | 3+ | |

| Effect | Proportion Instable | Instable Markers | Evaluable Markers/Total Analyzed Markers |

| MSS | 15% | 16 | 105/110 |

| Gene | Variant | Genotype | Drug |

| MTHFR (NM_005957) | c.665C>T rs1801133 | G/A | Metotrexato |

4. DISCUSSION

5. CONCLUSION

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kurman RJ, World Health Organization. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs: [this book reflects the views of a working group that convened for a consensus and editorial meeting at the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, 13-15 June 2013]. Lyon: Internat. Agency For Research On Cancer; 2014.

- Mazur MT. Atypical polypoid adenomyomas of the endometrium. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1981 Jul;5(5):473–82. [CrossRef]

- Heatley MK. Atypical polypoid adenomyoma: a systematic review of the English literature. Histopathology. 2006 Apr;48(5):609–10. [CrossRef]

- Němejcová K, Kenny SL, Laco J, Škapa P, Staněk L, Zikán M, et al. Atypical Polypoid Adenomyoma of the Uterus. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2015 Aug;39(8):1148–55. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Tian L, Liu G. A clinicopathological review of 203 cases of atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus. J Clin Med. 2023;12(4):1511. [CrossRef]

- Kihara A, Amano Y, Yoshimoto T, Matsubara D, Fukushima N, Fujiwara H, et al. Stromal p16 Expression Helps Distinguish Atypical Polypoid Adenomyoma From Myoinvasive Endometrioid Carcinoma of the Uterus. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2019 Nov 1;43(11):1526–35. [CrossRef]

- McCluggage WG. A practical approach to the diagnosis of mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumours of the uterus. Modern Pathology. 2015 Dec 30;29(S1)–91. [CrossRef]

- Worrell HI, Sciallis AP, Skala SL. Patterns of SATB2 and p16 reactivity aid in the distinction of atypical polypoid adenomyoma from myoinvasive endometrioid carcinoma and benign adenomyomatous polyp on endometrial sampling. Histopathology [Internet]. 2021 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Dec 14];79(1):96–105. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33459390/. [CrossRef]

- Solima E, Liprandi V, Belloni GM, Vignali M, Busacca M. Recurrent atypical polypoid adenomyoma and pregnancy: A new conservative approach with levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Gynecologic Oncology Reports [Internet]. 2017 Aug 1 [cited 2024 Apr 4];21:84–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28761925/. [CrossRef]

- ONCOSEGO. Oncoguía cáncer de endometrio (2023) [Internet]. ONCOSEGO. [cited 2024 Apr 4]. Available from: https://oncosego.sego.es/oncoguia-cancer-de-endometrio-2023.

- Rizzuto I, Nicholson R, Dickinson K, Juang HJ, MacNab W, B. Rufford. A case of incidental endometrial adenocarcinoma diagnosed in early pregnancy and managed conservatively. Gynecologic Oncology Reports [Internet]. 2019 May 1 [cited 2023 Dec 15];28:101–3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6449706/. [CrossRef]

- Masciullo V, Susini T, Corrado G, Stepanova M, Baroni A, Renda I, et al. Nuclear Expression of β-Catenin Is Associated with Improved Outcomes in Endometrial Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland) [Internet]. 2022 Oct 3 [cited 2024 Jan 10];12(10):2401. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36292090/. [CrossRef]

- Zhao R, Choi BY, Lee M-H, Bode AM, Dong Z. Implications of genetic and epigenetic alterations of CDKN2A (p16 INK4a ) in cancer. EBioMedicine [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2024 Jan 10];8:30–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27428416/. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh GG, Lodge AJ, Watson P, Hall AG, Wood K, Anderson JJ, et al. NCL-CD10–270: A new monoclonal antibody recognizing CD10 in paraffin-embedded tissue. Am J Pathol [Internet]. 1999;154(1):77–82. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65253-4. [CrossRef]

- Zhao W, Cui M, Zhang R, Shen X, Xiong X, Ji X, et al. IFITM1, CD10, SMA, and h-caldesmon as a helpful combination in differential diagnosis between endometrial stromal tumor and cellular leiomyoma. BMC Cancer [Internet]. 2021 Sep 23 [cited 2024 Jan 10];21(1):1047. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34556086/. [CrossRef]

- IMEGEN [Internet]. Imegen. 2022 Available from: http://www.imegen.es/datagenomics.

- Martínez-Fernández P, Pose P, Dolz-Gaitón R, García A, Trigo-Sánchez I, Rodríguez-Zarco E, et al. Comprehensive NGS Panel Validation for the Identification of Actionable Alterations in Adult Solid Tumors. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021 Apr 29;11(5):360. [CrossRef]

- Human Genome Variation Society. [Internet]. [cited 2024 May 10]. Available from: https://www.hgvs.org.

- Garraway LA. Genomics-Driven Oncology: Framework for an Emerging Paradigm. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013 May 20;31(15):1806–14. [CrossRef]

- Mosele F, Remon J, Mateo J, Westphalen CB, Barlesi F, Lolkema MP, et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with metastatic cancers: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann Oncol [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 May 15];31(11):1491–505. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32853681/. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi H, Yoshida T, Matsumoto T, Kameda Y, Takano Y, Tazo Y, et al. Frequent β-catenin gene mutations in atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus. Human Pathology [Internet]. 2014 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Jan 10];45(1):33–40. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24182564/. [CrossRef]

- Ota S, Catasus L, Matias-Guiu X, Bussaglia E, Lagarda H, Pons C, et al. Molecular pathology of atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus. Human Pathology. 2003 Aug;34(8):784–8. [CrossRef]

- Yao YB, Xiao CF, Lu JG, Wang C. Caldesmon: Biochemical and Clinical Implications in Cancer. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021 Feb 18;9. [CrossRef]

- Buza N, Hui P. Immunohistochemistry in Gynecologic Pathology: An Example-Based Practical Update. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2017 Aug 1;141(8):1052–71. [CrossRef]

- Ohishi Y, Kaku T, Kobayashi H, Aishima S, Umekita Y, Wake N, et al. CD10 immunostaining distinguishes atypical polypoid adenomyofibroma (atypical polypoid adenomyoma) from endometrial carcinoma invading the myometrium. Human Pathology [Internet]. 2008 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Apr 5];39(10):1446–53. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18619643/. [CrossRef]

- Lu B, Yu M, Shi H, Chen Q. Atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus: A reappraisal of the clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features. Pathology - Research and Practice. 2019 Apr;215(4):766–71. [CrossRef]

- Terada T. Atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus: an immunohistochemical study on 5 cases. Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 2011 Oct;15(5):338–41. [CrossRef]

- Gao C, Wang Y, Broaddus R, Sun L, Xue F, Zhang W. Exon 3 mutations of CTNNB1 drive tumorigenesis: a review. Oncotarget [Internet]. 2017 Dec 27 [cited 2024 Apr 23];9(4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23695. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen VHL, Hough R, Bernaudo S, Peng C. Wnt/β-catenin signalling in ovarian cancer: Insights into its hyperactivation and function in tumorigenesis. Journal of Ovarian Research. 2019 Dec;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Katoh M, Katoh M. Molecular genetics and targeted therapy of WNT-related human diseases (Review). International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2017 Jul 19;

- Yu F, Yu C, Li F, Zuo Y, Wang Y, Yao L, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cancers and targeted therapies. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2021 Aug 30;6(1). [CrossRef]

- Moroney MR, Woodruff E, Qamar L, Bradford AP, Wolsky R, Bitler BG, et al. Inhibiting Wnt/beta-catenin in CTNNB1 -mutated endometrial cancer. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2021 May 26;60(8):511–23.

- Chakraborty E, Sarkar D. Emerging Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). Cancers [Internet]. 2022 Jun 4;14(11):2798. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9179883/. [CrossRef]

- Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017 Jun 8;357(6349):409–13. [CrossRef]

- Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, Miya J, Wing MR, Chen HZ, et al. Landscape of Microsatellite Instability Across 39 Cancer Types. JCO precision oncology [Internet]. 2017;2017. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29850653/. [CrossRef]

- Yan L, Zhang W. Precision medicine becomes reality—tumor type-agnostic therapy. Cancer Communications. 2018 Mar 31;38(1).

- Luchini C, Bibeau F, Ligtenberg MJL, Singh N, Nottegar A, Bosse T, et al. ESMO recommendations on microsatellite instability testing for immunotherapy in cancer, and its relationship with PD-1/PD-L1 expression and tumour mutational burden: a systematic review-based approach. Annals of Oncology. 2019 Aug;30(8):1232–43.

- PharmGKB [Internet]. PharmGKB. 2019. Available from: https://www.pharmgkb.org/.

| MOLECULAR STUDY | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | PMS2 | MSH6 | P53 | MLH1 | CTNNB1 | P16 | |

| OWN CASE | 1 | + | + | ||||

| NEMEJCOVA | 21 | 2+ | 2+ | N | 3+ | ||

| YUE | 99 | 3+ | 3+ | 2+ | + | 3+ | |

| TAKASHI | 7 | ||||||

| OTA | 6 | N | 3+ | - | |||

| LU | 36 | N | |||||

| WORREL | 32 | 3+ | |||||

| KIHARA | 12 | 2+ | 3+ | ||||

| MARKERS | Atypical Polypoid Adenomyoma | Endometrial Adenocarcinoma |

|---|---|---|

| B-catenina | + | + |

| P16 | + | - |

| RE | + | + |

| PR | + | + |

| Pancitoqueratina | + | + |

| CD10 | - | + |

| Caldesmon | - | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).