Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

17 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. The Theoretical Background of the Study

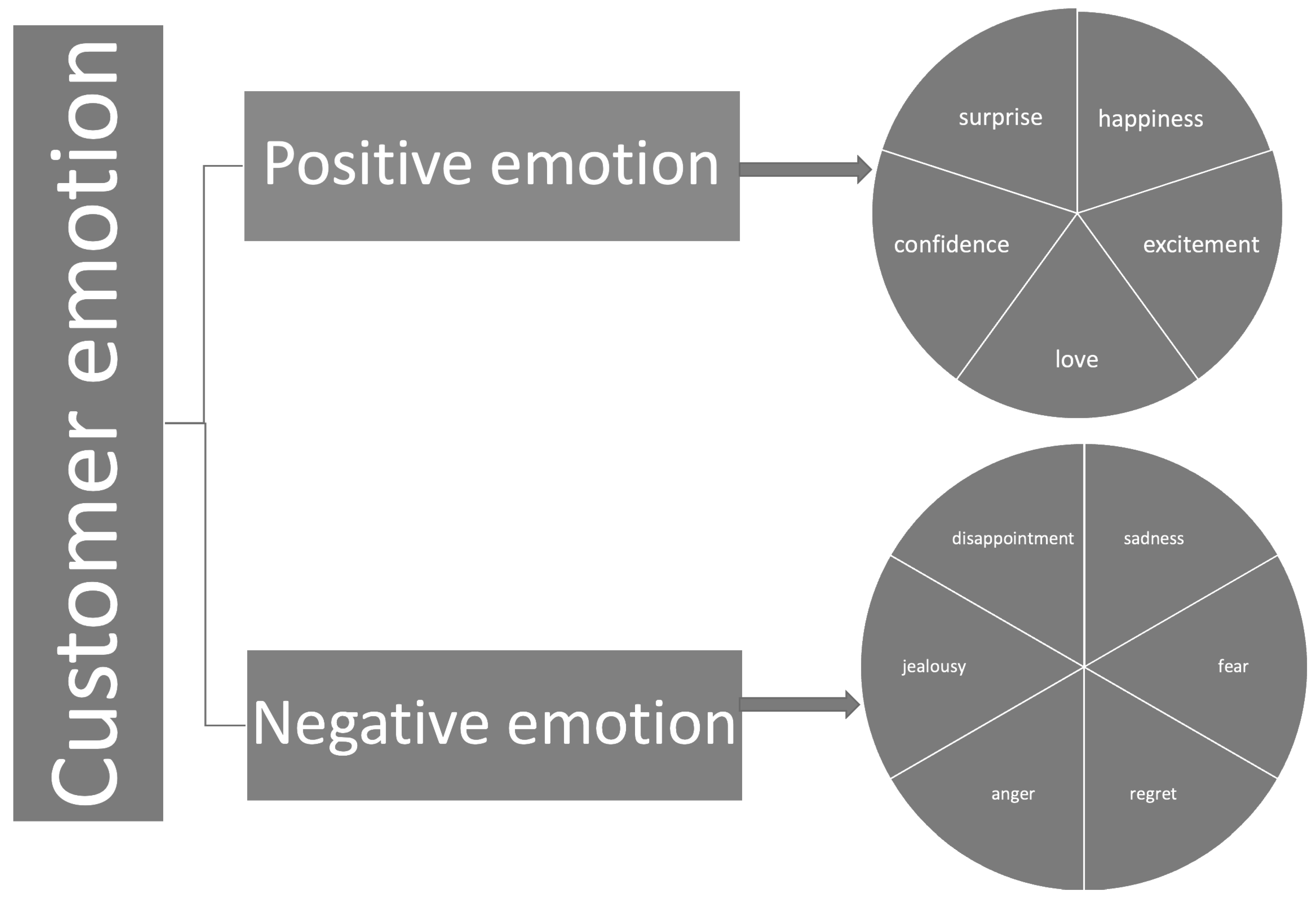

2.1.1. Customer Emotion

2.1.2. Influences on Customer Emotional Purchases

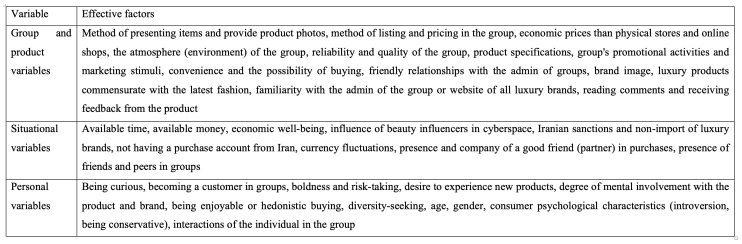

- Personal Factors

- Contextual variables

- Merchandise and ecological factors

2.2. Foundation of the Experiment

3. Research Approach

3.1. Thematic Examination

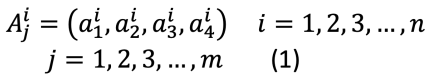

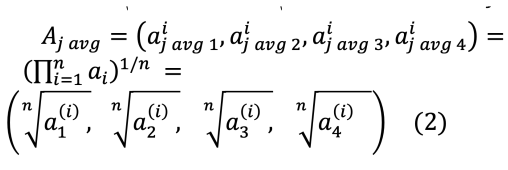

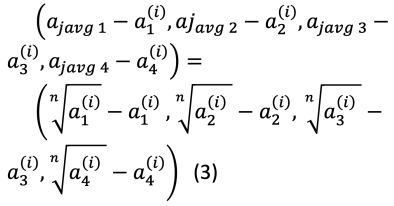

3.2. Fuzzy Delphi Technique

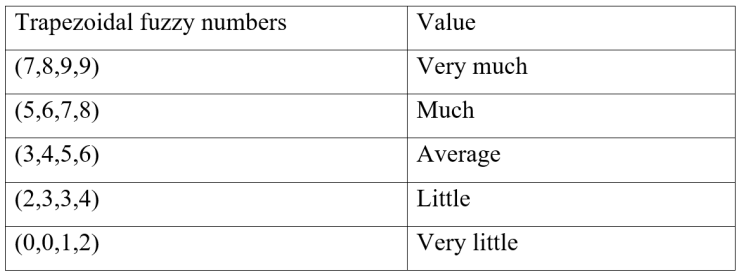

4. Findings

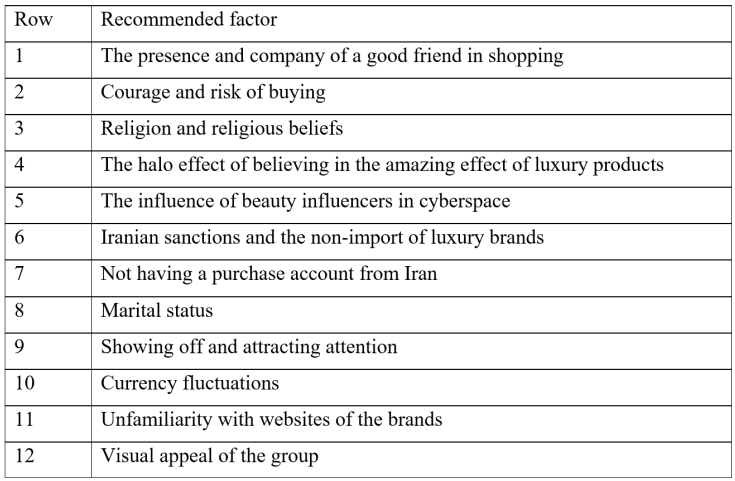

4.1. Content Analysis Outcomes

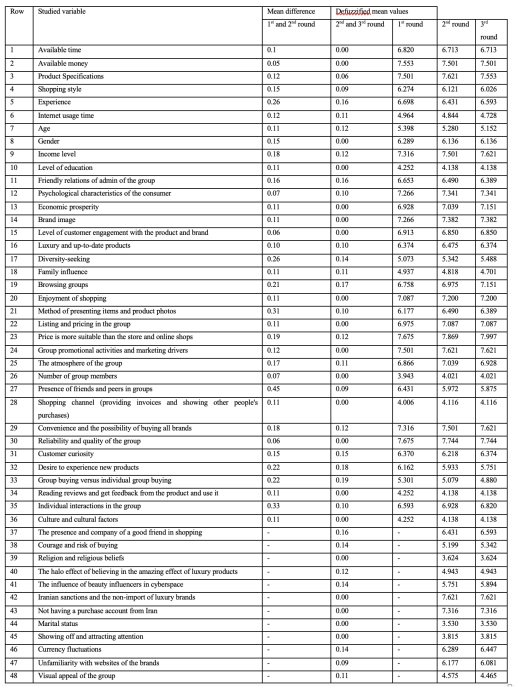

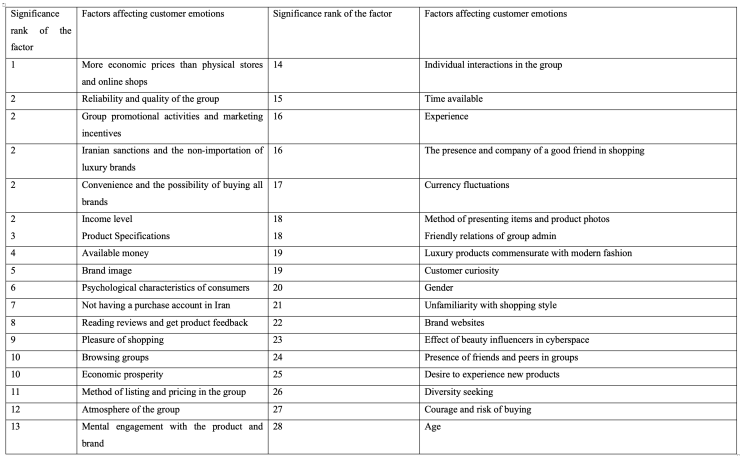

4.2. Fuzzy Delphi Approach

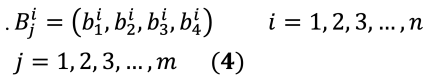

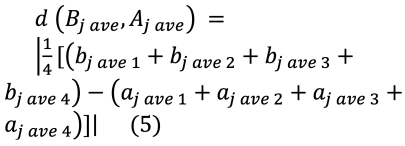

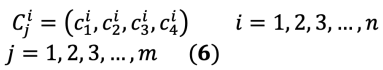

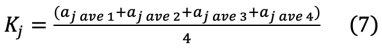

|

5. Discussion

6. Limitations of the Study

- (1) This study focuses exclusively on customer emotions within the luxury cosmetics sector, limiting its generalizability to other industries and product categories. Future research should explore emotional dynamics across diverse contexts and products to enrich understanding in this domain.

- (2) The study’s sample primarily comprises members of Telegram groups engaged in luxury cosmetics, predominantly female. Consequently, caution is advised when extrapolating findings to broader consumer demographics. Future studies should strive for more representative samples to enhance the applicability of findings across diverse consumer segments.

7. Future Studies

- (1) Given the first limitation, researchers are encouraged to explore the broader dimensions of customer emotions in online shopping across various virtual platforms and product categories, contributing to enhanced consumer insights in Iran.

- (2) Future studies could benefit from examining more diverse consumer demographics, including both male and female participants, or conducting nationwide studies to capture broader consumer sentiment.

Acknowledgments

References

- Jain, S. Factors affecting sustainable luxury purchase behavior: A conceptual framework. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 2019, 31, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R. The effect of consumption emotions on satisfaction and word-of-mouth communications. Psychology & Marketing 2007, 24, 1085–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Zam, M.; Tavakoli, M.; Ramezanian, H.; Rezasoltani, A. The relationship between consuming fashion and self-confidence on the buying behaviour in the clothing market as a mediator 2022.

- Zam, M.; Rezasoltani, A.; Ramezanian, H.; Tavakoli, M. Effects of psychological factors on customer behavior in e-transactions 2022.

- Zam, M.; Tavakoli, M.; Ramezanian, H.; Rezasoltani, A. Assessing the different aspects of consuming fashion and the role of self-confidence on the buying behaviour of fashion consumers in the clothing market as a mediator. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2209.02367. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.Y.; Liao, J.C. The influence of store image and product perceived value on consumer purchase intention. International Journal of Advanced Scientific Research and Technology 2012, 2, 306–321. [Google Scholar]

- Husnain, M.; Rehman, B.; Syed, F.; Akhtar, M.W. Personal and in-store factors influencing impulse buying behavior among generation Y consumers of small cities. Business Perspectives and Research 2019, 7, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, O.Y.A.; Ardyan, E. The influencing factors of impulsive buying behaviour in Transmart Carrefour Sidoarjo 2018.

- Kim, J.; Lennon, S.J. Effects of reputation and website quality on online consumers’ emotion, perceived risk and purchase intention: Based on the stimulus-organism-response model. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 2013.

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Muskat, B.; Del Chiappa, G. Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of travel research 2017, 56, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senturk, H.A.; Cizer, E.O.; Sezer, T. The Effects of Real-Time Content Marketing on Consumer Emotions and Behaviors: An Analysis on COVID-19 Pandemic Period. In Cases on Digital Strategies and Management Issues in Modern Organizations; IGI Global, 2022; pp. 300–329.

- Nguyen, T.M.H. The impact of emotions on customer experience through using mobile application for food ordering in Finland 2018.

- Plutchik, R.; Kellerman, H. Emotion Profile Index; Western Psychological Services, 1974.

- Boyle, G.J. Reliability and validity of Izard’s differential emotions scale. Personality and individual Differences 1984, 5, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronvoll, B. Negative emotions and their effect on customer complaint behaviour. Journal of Service Management 2011.

- Khan, N.; Hui, L.H.; Chen, T.B.; Hoe, H.Y. Impulse buying behaviour of generation Y in fashion retail. International Journal of Business and Management 2016, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, G.; Lee, Y.; Choi, S. Customer emotions and their triggers in luxury retail: Understanding the effects of customer emotions before and after entering a luxury shop. Journal of Business Research 2016, 69, 5809–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souki, G.Q.; Antonialli, L.M.; Barbosa, A.A.d.S.; Oliveira, A.S. Impacts of the perceived quality by consumers’ of à la carte restaurants on their attitudes and behavioural intentions. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2020, 32, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.; Wu, C.; Tsai, H. The impact of service quality on positive consumption emotions in resort and hotel spa experiences. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 2015, 24, 155–179. [Google Scholar]

- Pappas, I.O.; Kourouthanassis, P.E.; Giannakos, M.N.; Chrissikopoulos, V. Explaining online shopping behavior with fsQCA: The role of cognitive and affective perceptions. Journal of Business Research 2016, 69, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkonen, M.; Riekkinen, J.; Frank, L.; Jussila, J. The effects of positive and negative emotions during online shopping episodes on consumer satisfaction, repurchase intention, and recommendation intention. Bled eConference. University of Maribor, 2019.

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Prayag, G. Perceived quality and service experience: Mediating effects of positive and negative emotions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 2019, 28, 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- Verplanken, B.; Herabadi, A. Individual differences in impulse buying tendency: Feeling and no thinking. European Journal of personality 2001, 15, S71–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciunova-Shuleska, A. The impact of situational, demographic, and socioeconomic factors on impulse buying in the republic of Macedonia. Journal of East-West Business 2012, 18, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgaiyan, A.J.; Verma, A. Does urge to buy impulsively differ from impulsive buying behaviour? Assessing the impact of situational factors. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2015, 22, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Jalees, T.; Qabool, S.; Zaman, S.I. The effects of personality, culture and store stimuli on impulsive buying behavior: Evidence from emerging market of Pakistan. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2020, 32, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sivakumaran, B.; Marshall, R. Impulse buying and variety seeking: A trait-correlates perspective. Journal of Business research 2010, 63, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, S.E.; Ferrell, M.E. Impulse buying: Modeling its precursors. Journal of retailing 1998, 74, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruganantham, G.; Bhakat, R.S. A review of impulse buying behavior. International journal of marketing studies 2013, 5, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Gu, L.; Aiken, M. A study of the impact of individual differences on online shopping. International Journal of E-Business Research (IJEBR) 2010, 6, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.H. The effects of product stimuli and social stimuli on online impulse buying in live streams. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Management of e-Commerce and e-Government, 2020, pp. 31–35.

- Ali Taha, V.; Pencarelli, T.; Škerháková, V.; Fedorko, R.; Košíková, M. The use of social media and its impact on shopping behavior of Slovak and Italian consumers during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Babapour, H. Critical variables for assessing the effectiveness of electronic customer relationship management systems in online shopping. Kybernetes 2022.

- Khan, R.U.; Salamzadeh, Y.; Iqbal, Q.; Yang, S. The impact of customer relationship management and company reputation on customer loyalty: The mediating role of customer satisfaction. Journal of Relationship Marketing 2022, 21, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.a.; Han, S.L. Effects of experiential motivation and customer engagement on customer value creation: Analysis of psychological process in the experience-based retail environment. Journal of Business Research 2020, 120, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, N.U.; Nisa, U.; Imam, S.S. Investigating the factors that impact online shopping and sales promotion on consumer’s impulse buying behavior: a gender-based comparative study in the UAE. International Journal of Business and Administrative Studies 2021, 7, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdari, M.; Pawar, A.; Li, H.; Tajdari, F.; Maqsood, A.; Cleary, E.; Saha, S.; Zhang, Y.J.; Sarwark, J.F.; Liu, W.K. Image-based modelling for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: mechanistic machine learning analysis and prediction. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2021, 374, 113590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarvirdizadeh, B.; Golgouneh, A.; Tajdari, F.; Khodabakhshi, E. A novel online method for identifying motion artifact and photoplethysmography signal reconstruction using artificial neural networks and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system. Neural Computing and Applications 2020, 32, 3549–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, A.; Khodayari, A.; Kamali, A.; Tajdari, F.; Hosseinkhani, N. New fuzzy solution for determining anticipation and evaluation behavior during car-following maneuvers. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of automobile engineering 2018, 232, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodayari, A.; Ghaffari, A.; Kamali, A.; Tajdari, F. A new model of car following behavior based on lane change effects using anticipation and evaluation idea. Iranian Journal of Mechanical Engineering Transactions of the ISME 2015, 16, 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tajdari, F.; Kabganian, M.; Rad, N.F.; Khodabakhshi, E. Robust control of a 3-dof parallel cable robot using an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system. 2017 Artificial Intelligence and Robotics (IRANOPEN). IEEE, 2017, pp. 97–101.

- Tarvirdizadeh, B.; Golgouneh, A.; Khodabakhshi, E.; Tajdari, F. An assessment of a similarity between the right and left hand photoplethysmography signals, using time and frequency features of heart-rate-variability signal. 2017 IEEE 4th international conference on knowledge-based engineering and innovation (KBEI). IEEE, 2017, pp. 0588–0594.

- Tajdari, F.; Toulkani, N.E.; Zhilakzadeh, N. Intelligent optimal feed-back torque control of a 6dof surgical rotary robot. 2020 11th Power Electronics, Drive Systems, and Technologies Conference (PEDSTC). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–6.

- Tajdari, F.; Ghaffari, A.; Khodayari, A.; Kamali, A.; Zhilakzadeh, N.; Ebrahimi, N. Fuzzy control of anticipation and evaluation behaviour in real traffic flow. 2019 7th International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics (ICRoM). IEEE, 2019, pp. 248–253.

- Cheng, C.H.; Lin, Y. Evaluating the best main battle tank using fuzzy decision theory with linguistic criteria evaluation. European journal of operational research 2002, 142, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdari, F.; Ebrahimi Toulkani, N. Implementation and intelligent gain tuning feedback–based optimal torque control of a rotary parallel robot. Journal of Vibration and Control 2022, 28, 2678–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdari, F.; Tajdari, M.; Rezaei, A. Discrete time delay feedback control of stewart platform with intelligent optimizer weight tuner. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2021, pp. 12701–12707.

- Tajdari, F.; Toulkani, N.E.; Nourimand, M. Intelligent architecture for car-following behaviour observing lane-changer: Modeling and control. 2020 10th International Conference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE). IEEE, 2020, pp. 579–584.

- Girbés-Juan, V.; Armesto, L.; Hernández-Ferrándiz, D.; Dols, J.; Sala, A.; Zhang, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Guo, L.; Chen, J.; others. Simultaneous Intelligent Anticipation and Control of Follower Vehicle Observing Exiting Lane Changer........................................... F. Tajdari, A. Golgouneh, A. Ghaffari, A. Khodayari, A. Kamali, and N. Hosseinkhani 8567 Road Garbage Segmentation and Cleanliness Assessment Based on Semantic Segmentation Network for Cleaning Vehicles....................................................... J. Liao, X. Luo, L. Cao, W. Li, X. Feng, J. Li, and F. Yuan 8578 Two-Stage Synthetic Optimization of Supercapacitor-Based Energy Storage Systems, Traction Power Parameters and.

- Tajdari, F.; Golgouneh, A.; Ghaffari, A.; Khodayari, A.; Kamali, A.; Hosseinkhani, N. Simultaneous intelligent anticipation and control of follower vehicle observing exiting lane changer. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2021, 70, 8567–8577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdari, F. Adaptive time-delay estimation and control of optimized Stewart robot. Journal of Vibration and Control 2022, p. 10775463221137141.

- Tajdari, M.; Tajdari, F.; Shirzadian, P.; Pawar, A.; Wardak, M.; Saha, S.; Park, C.; Huysmans, T.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; et al. Next-generation prognosis framework for pediatric spinal deformities using bio-informed deep learning networks. Engineering with Computers 2022, 38, 4061–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdari, F.; others. Optimal and adaptive controller design for motorway traffic with connected and automated vehicles 2023.

- Dalkey, N.; Helmer, O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management science 1963, 9, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdari, F.; Roncoli, C.; Papageorgiou, M. Feedback-based ramp metering and lane-changing control with connected and automated vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2020, 23, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golgouneh, A.; Bamshad, A.; Tarvirdizadeh, B.; Tajdari, F. Design of a new, light and portable mechanism for knee CPM machine with a user-friendly interface. 2016 Artificial Intelligence and Robotics (IRANOPEN). IEEE, 2016, pp. 103–108.

- Tajdari, F.; Roncoli, C.; Bekiaris-Liberis, N.; Papageorgiou, M. Integrated ramp metering and lane-changing feedback control at motorway bottlenecks. 2019 18th European Control Conference (ECC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 3179–3184.

- Tajdari, F.; Khodabakhshi, E.; Kabganian, M.; Golgouneh, A. Switching controller design to swing-up a two-link underactuated robot. 2017 IEEE 4th International Conference on Knowledge-Based Engineering and Innovation (KBEI). IEEE, 2017, pp. 0595–0599.

- Tajdari, F.; Kabganian, M.; Khodabakhshi, E.; Golgouneh, A. Design, implementation and control of a two-link fully-actuated robot capable of online identification of unknown dynamical parameters using adaptive sliding mode controller. 2017 Artificial Intelligence and Robotics (IRANOPEN). IEEE, 2017, pp. 91–96.

- Tajdari, F.; Toulkani, N.E.; Zhilakzadeh, N. Semi-real evaluation, and adaptive control of a 6dof surgical robot. 2020 11th Power Electronics, Drive Systems, and Technologies Conference (PEDSTC). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–6.

- Tajdari, F.; Roncoli, C. Adaptive traffic control at motorway bottlenecks with time-varying fundamental diagram. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2021, 54, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezasoltani, A.; Saffari, E.; Konjani, S.; Ramezanian, H.; Zam, M. Exploring the Viability of Robot-supported Flipped Classes in English for Medical Purposes Reading Com-prehension. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2208.07442. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Yuan, T.; Huysmans, T.; Elkhuizen, W.S.; Tajdari, F.; Song, Y. Posture-invariant three dimensional human hand statistical shape model. Journal of Computing and Information Science in Engineering 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdari, F.; Huysmans, T.; Yang, Y.; Song, Y. Feature preserving non-rigid iterative weighted closest point and semi-curvature registration. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2022, 31, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdari, F.; Eijck, C.; Kwa, F.; Versteegh, C.; Huysmans, T.; Song, Y. Optimal position of cameras design in a 4D foot scanner. International design engineering technical conferences and computers and information in engineering conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2022, Vol. 86212, p. V002T02A044.

- Tajdari, F.; Kwa, F.; Versteegh, C.; Huysmans, T.; Song, Y. Dynamic 3d mesh reconstruction based on nonrigid iterative closest-farthest points registration. International design engineering technical conferences and computers and information in engineering conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2022, Vol. 86212, p. V002T02A051.

- Minnoye, A.L.; Tajdari, F.; Doubrovski, E.L.; Wu, J.; Kwa, F.; Elkhuizen, W.S.; Huysmans, T.; Song, Y. Personalized product design through digital fabrication. International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2022, Vol. 86212, p. V002T02A054.

- Tajdari, M.; Tajdari, F.; Pawar, A.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.K. 2D to 3D volumetric reconstruction of human spine for diagnosis and prognosis of spinal deformities. Conference: 16th US national congress on computational mechanics, 2021.

- Tajdati, F.; Huysmans, T.; Song, Y. Non-rigid registration via intelligent adaptive feedback control. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 2023, pp. 1–16.

- Tajdati, F.; Huysmans, T.; Xu, J.; Yao, X.; Song, Y. 4D Feet: Registering Walking Foot Shapes Using Attention Enhanced Dynamic-Synchronised Graph Convolutional LSTM Network. 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). IEEE, 2019, pp. 10441–10450.

- Aghayari, J.; Valmohammadi, C.; Alborzi, M. Research Article Explaining the Effective Factors on Digital Transformation Strategies in the Telecom Industry of Iran Using the Delphi Method 2022.

- Murgante, B.; Eskandari Sani, M.; Pishgahi, S.; Zarghamfard, M.; Kahaki, F. Factors affecting the Lut desert tourism in Iran: Developing an interpretive-structural model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdari, F.; Ramezanian, H.; Paydarfar, S.; Lashgari, A.; Maghrebi, S. Flow metering and lane-changing optimal control with ramp-metering saturation. 2022 CPSSI 4th International Symposium on Real-Time and Embedded Systems and Technologies (RTEST). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6.

- Tajdari, F.; Roncoli, C. Online set-point estimation for feedback-based traffic control applications. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2207.13467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdari, F. Online set-point estimation for feedback-based traffic control applications. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023, 24, 10830–10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, N.F.; Yousefi-Koma, A.; Tajdari, F.; Ayati, M. Design of a novel three degrees of freedom ankle prosthesis inspired by human anatomy. 2016 4th International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics (ICROM). IEEE, 2016, pp. 428–432.

- Rad, N.F.; Ayati, M.; Basaeri, H.; Yousefi-Koma, A.; Tajdari, F.; Jokar, M. Hysteresis modeling for a shape memory alloy actuator using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system. 2015 3Rd RSI international conference on robotics and mechatronics (ICROM). IEEE, 2015, pp. 320–324.

- Tajdari, F. Advancing non-rigid 3D/4D human mesh registration for ultra-personalization. Ph.D. dissertation, Delft Univ. Technol., Delft, Netherlands 2023.

- Tajdari, F.; Roncoli. Online set-point estimation for feedback-based traffic control applications. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2207.13467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncoli, C.; Tajdari, F.; Bekiaris-Liberisb, N.; Papageorgioub, M. Integrated control of motorway bottlenecks via flow metering and lane assignment.

- Roncolia, C.; Tajdaria, F.; Bekiaris-Liberisb, N.; Papageorgioub, M. Integrated control of motorway bottlenecks via flow metering and lane assignment. transportation at EPFL, heart conference 2018.

- Tajdari, F.; Ramezanian, H.; Paydarfar, S.; Lashgari, A.; Maghrebi, S. Optimal flow metering and lane-changing control with ramp-metering saturation. IEEE - The 4th Cyber-Physical Systems Society of Iran (CPSSI) International Symposium on Real-Time and Embedded Systems and Technologies (RTEST); , 2022. [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).