1. Introduction and Motivation

The motivation for investigating the distribution of prime numbers over the real line

first reflected in the writings of famous mathematician

Ramanujan, as evident from his letters [[

12],pp.

xxiii-xxx , 349-353] to one of the most prominent mathematicians of 20

th century,

G. H. Hardy during the months of Jan/Feb of 1913, which are testaments to several strong assertions about

prime numbers, especaially the

Prime Counting Function,

[

6].

In the following years, Hardy himself analyzed some of thoose results [

13,

14], and even wholeheartedly acknowledged them in many of his publications, one such notable result is the

Prime Number Theorem [

9].

Ramanujan provided several inequalities regarding the behaviour and the asymptotic nature of . One of such relation can be found in the notebooks written by Ramanujan himself has the following claim.

Theorem 1.1. (Ramanujan’s Inequality [1]) For x sufficiently large, we shall have,

Worth mentioning that, Ramanujan indeed provided a simple, yet unique solution in support of his claim.

One immediate question which may pop up inside the head of any Number Theorist is that, what is meant by the term

"large"? Apparently, over many years and even recently, a huge amount of effort has been put up by eminent researchers from all over the world in order to study

Ramanujan’s Inequality, and focusing on understanding the behaviour of

and any other Arithmetic Function associated to it. For example, it can be found in the work of

Wheeler, Keiper, and Galway,

Hassani [[

11], Theorem 1.2]. Later on thanks to

Dudek and

Platt [[

2], Theorem 1.2],

Mossinghoff and

Trudgian [

16] and

Axler [

15], it has been well established that, a large proportion of posiive reals

x falls under the category for which the inequality in fact is true.

In recent years, some attempts have indeed been made in order to derive other versions analogous to the

Ramanujan’s Conjecture.

Hassani [

8] came up with a generalization of (

1) increasing the power upto

. Furthermore, he also studied (

1) extensively for different cases [

11], and eventually claimed that, the inequality (

1) does in fact reverses if one can replace

e by some

satifying,

, although it retains the same sign for every

. In addition to providing several numerical justifications in support of his proposition, he also came up with a few inequalities using asymptotic relations involving

(cf. Theorem 2, 5 [

7]), one of which stated that, for large enough

x,

This article serves as a humble tribute to arguably the most famous mathematician that there ever was,

Srinivasa Ramanujan, and his stellar work on

, where we shall investigate certain higher degree polynomial functions in

for their asymptotic behaviour as compared to significantly higher values of

x, along with numerical estimates in support of justifying each and every result thus obtained in this process. We shall primarily discuss two major results in this area, namely:

In addition to above, we shall further look into the prospect of exploring the similar characteristics of functions when it involves weighted sums and logarithmic weighted sums of over small intervals. The two important results in this segment which we’ve proposed in this paper are:

Moreover, the later sections have been devoted towards attempting to generalize some of the proposed inequalities, as well as discussing about working with functions involving arbitrarily chosen polynomials in in a more generalized framework.

Before getting into the intricate details of this article, let us provide a brief overview of some important concepts involving

and the

Second Chebyshev Function [

5], which will be required extensively for establishing each and every result in later sections.

2. Important Derivations Regarding

We recall the definition of the

Prime Counting Function [

10,

13] ,

to be the number of

primes less than or equal to

. In addition to above, we further define the

Second Chebyshev Function as follows.

Definition 2.1. For every ,

Where, is the "Mangoldt Function" having the definition,

Applying the meromorphic properties of the

Riemann Zeta Function [

3] and that, it’s non-trivial zeros lies inside the critical strip,

, it can further be commented that [

4],

A priori an application of the

Prime Number Theorem [[

10], Theorem 2.2.1, pp. 4] allows us to utilize (

3) and obtain an estimate for

in terms of

.

Readers can refer to [[

4], Theorem (3.3)] in for a detailed solution of this result. We shall be thoroughly applying (

4) in the next two sections in order to study some specific polynomials involving

and their weighted sums and more significantly observe their asymptotic behaviour corresponding to increasing values of

x.

3. Inequalities Involving Polynomials in

3.1. Cubic Polynomial Inequality

The statement is as follows.

Theorem 3.1.

Let us consider the cubic polynomial of :

Given that is approximated by with a known error term, we can hypothesize that,

Furthermore, for sufficiently large values of x.

Proof. A priori from the order estimate between

and

as defined in (

4) (cf. [

4]), we compute the indivudual terms of

as follows,

and,

Furthermore,

Further simplification yields,

Finally,

And,

Combining all the terms (

7), (

10), (

11) and (

12), we obtain,

Considering the dominant terms and the contributions of each term separately as compared to the error term, we get,

Given the statement of the

Prime Number Theorem [

9,

10],

as

x approaches

∞, thus we consider the dominant terms for sufficiently large

x. Hence, substituting (

3) in (

13),

Since,

for sufficiently large

x ( observe that higher-order terms diminish as

x grows ), the dominant term is thus negative.

In coclusion, for sufficiently large values of

x, one shall have (

6) to satisfy and,

. □

Remark 3.2.

In other words, theCubic polynomial Inequalitycan be reformulated as, for sufficiently large values of x.

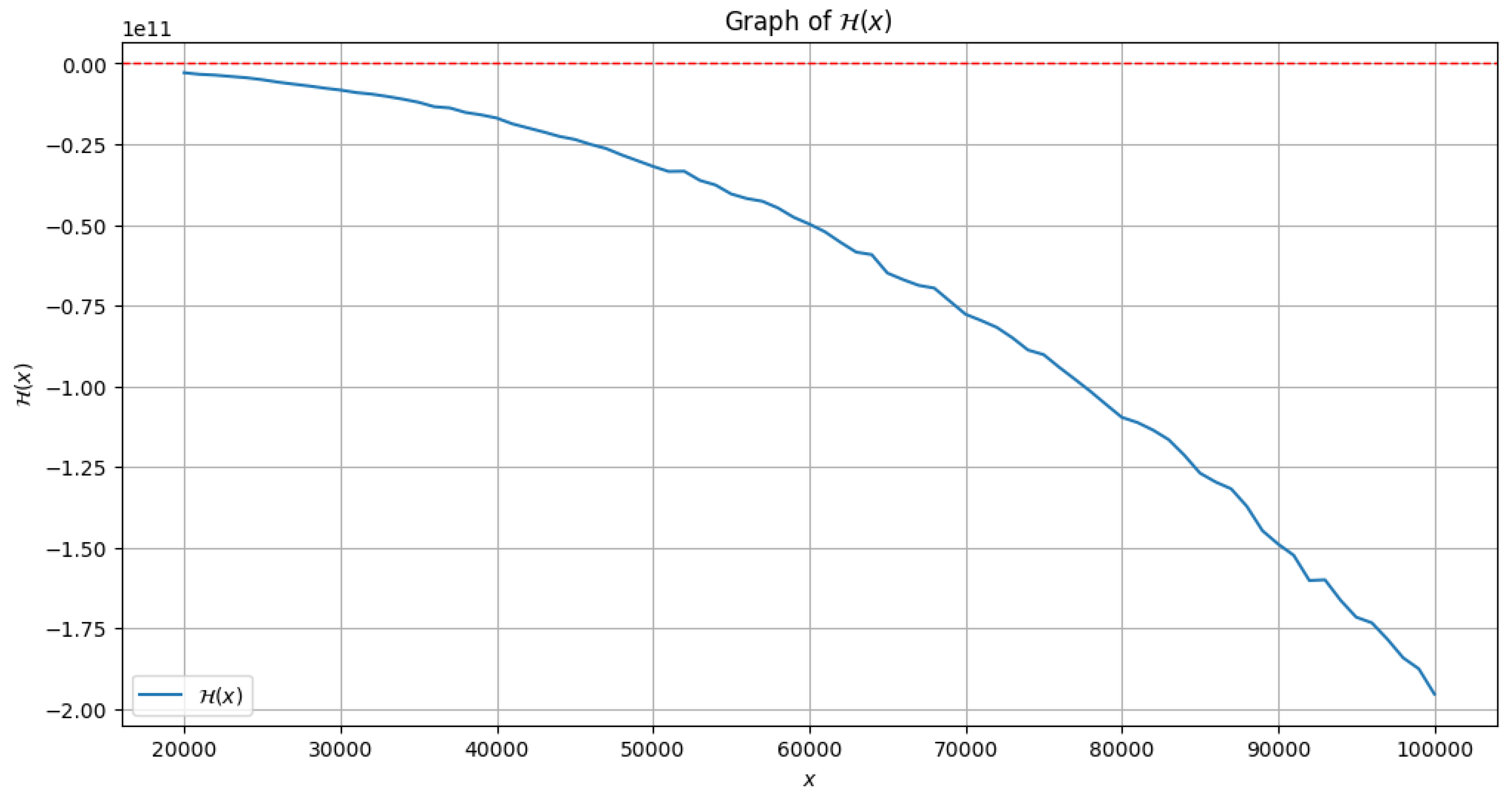

3.2. Numerical Estimates for

Important to note that, one can utilize

PYTHON programming language

1 in order to observe the plot of

as compared to

x. The following

Figure 1 shows the graph for

. Furthermore, rigorous computation using

MATHEMATICA1 yields the following values of

as mentioned in

Table 1 in the range,

. The data clearly suggests that, the function

is indeed

decreasing in this interval, hence, our claim (

15) can also be justified numerically.

3.3. Application: Equivalence with Ramanujan’s Inequality

The one question which might pop up at this point is to justify the sugnificance of studying inequalities like (

15) involving cubic polynomials in

. One such application which we shall observe in this section is the equivalence of the statements of the

Cubic Polynomial Inequality (cf. Theorem (3.1)) and the

Ramanujan’s Inequality (cf. Theorem (1.1)).

Assume that,

Hence, the statement goes as follows.

Theorem 3.3.

The Cubic Polynomial Inequality is equivalentto proving the Ramanujan’s Inequality [1][2]. In other words, if for large x, then, for sufficiently large x and vice versa.

Proof. A priori from (

4) of Theorem (2.2), we attain the derivations (

7) and (

8).

First, we approximate

,

Ignoring higher-order error terms. Estimating

in similar manner, we obtain,

First we assume , if possible that,

for sufficiently large values of

x. Given that

is the dominant term, for large

x, thus the second term in the expression of

will dominate the first and third terms due to the

factor in the numerator. Hence, to maintain the inequality, we must have,

Implying,

Dividing both sides by

,

N.B. Since is much larger than for large x, this approximation holds.

As for

, again, given the dominance of

,

Observe that, the leading term in

is negative, implying

.

Conversely, consider that,

. This implies,

Dividing both sides by

, we get,

Evaluate

,

Given the dominance of

, we can assert that,

Which simplifies to,

Dividing both sides by

,

The dominant term in (

22) indicates that the inequality

holds true for large enough

x. This completes the proof.

□

3.4. Higher-Degree Polynomial Inequality

Theorem 3.4.

For higher powers, let’s consider,

Then, the following holds true,

and for sufficiently large x we have, .

Proof. A priori using the relation (

4) (cf. [

4]) from Theorem (2.2), along with (

7) and (

8),

Now, we compute,

Moreover,

Subsequently, we approximate the rest of the terms of

as follows.

And,

Combining (

25), (

26), (

27), (

28) and (

29), and sorting out the dominant terms and their contributions towards the error term,

A simple application of (

3) yields,

Since

is positive for sufficiently large

x (higher-order terms diminish as

x grows), hence the dominant term is positive. Accordingly, the error term in the approximation is,

In conclusion, we assert that, (

24) indeed holds true, and

for sufficiently large enough

x. □

Remark 3.5.

We can also rephrase the result obtained from Theorem (3.4) in the form,

for sufficiently large values of x.

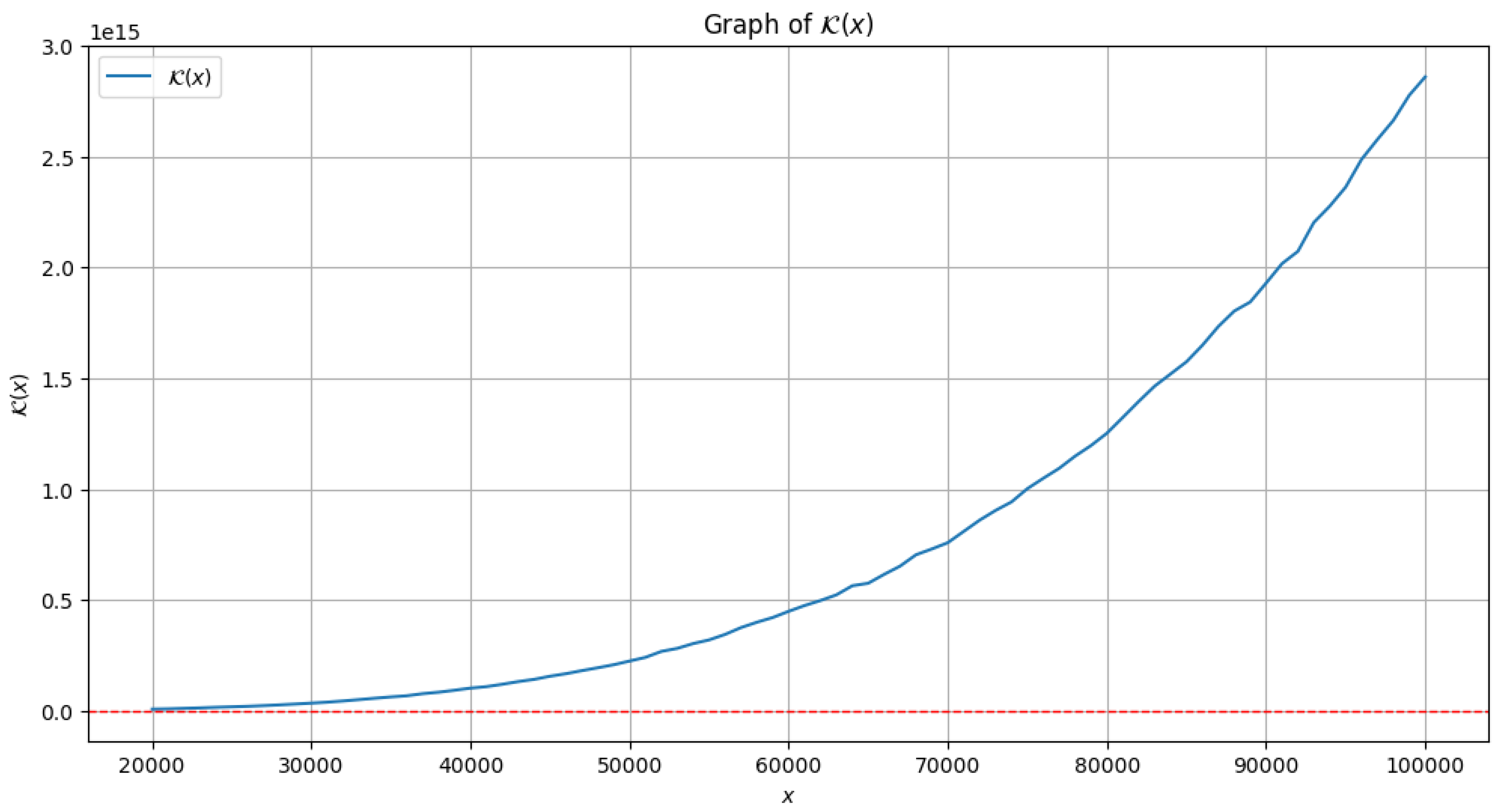

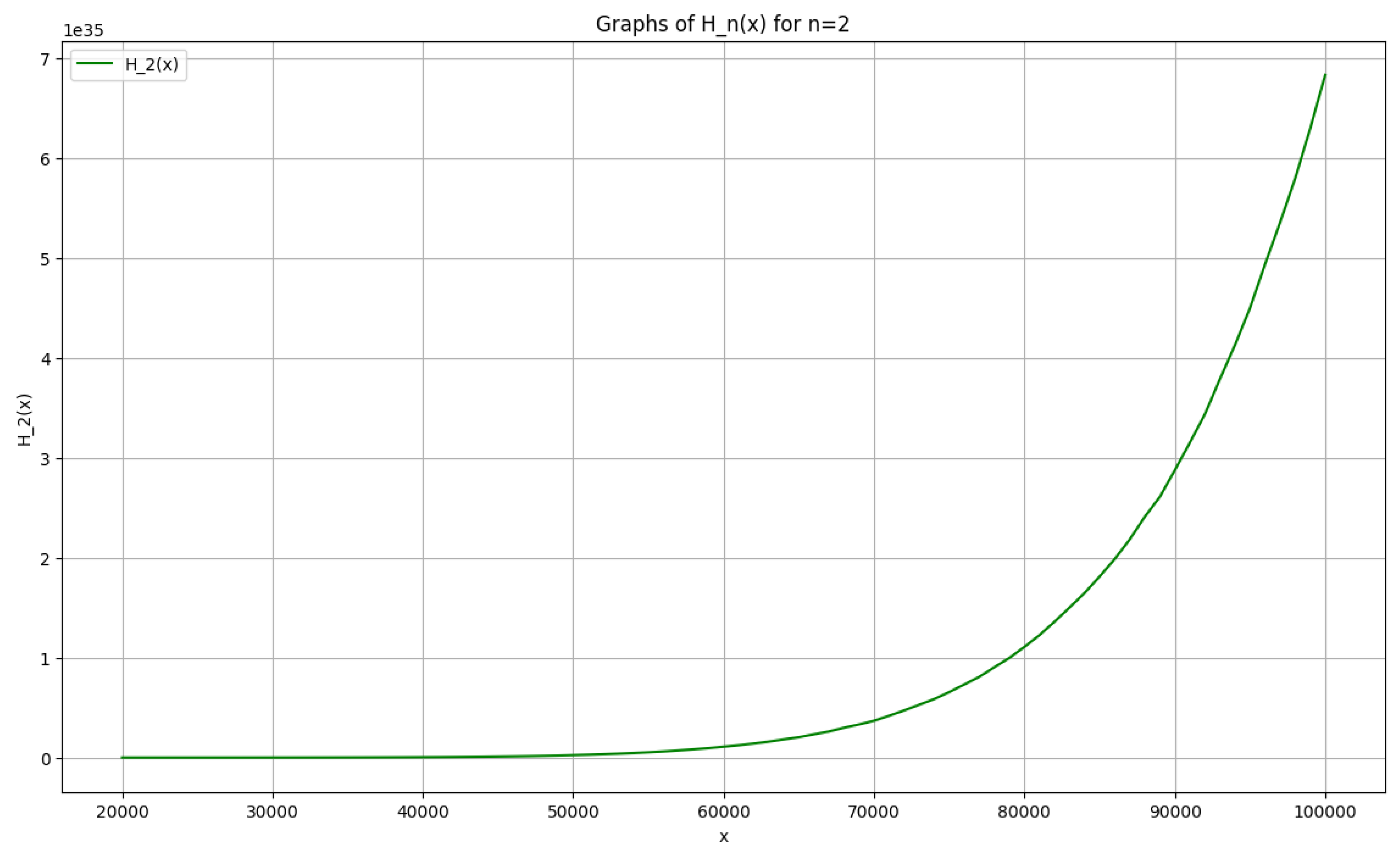

3.5. Numerical Estimates for

Important to observe that, one can apply

PYTHON programming language

1 in order to observe the plot of

as compared to

x. The following

Figure 2 shows the plot for

. Moreover, the following values of

can in fact be calculated using

MATHEMATICA1, as evident from

Table 2 in the range,

. Using the data one can clearly infer that,

is indeed

increasing in this interval, hence, our claim (

32) can be established numerically.

4. Quadratic Form Involving Sums of Prime Counting Function

4.1. Inequality Involving Weighted Sums of

Theorem 4.1.

Consider a quadratic form involving the sum of the prime counting function over smaller intervals,

For some fixed n, then we have the following approximation,

With for sufficiently large values of x.

Proof. For the proof, we evaluate terms inside the summand of

, a priori using the result (

4) (cf. [

4]) in Theorem (2.2).

Hence,

Similarly,

Squaring (

37) gives,

Ignoring the higher-order terms for the time being. Further computation yields,

Combining (

38) and (

39),

An important observation is that, the leading term of

is

x, so for large

x,

Therefore, using the leading term approximation, we can deduce,

Where,

denoting the n-th Harmonic Number, , being the Euler Constant.

As for the second term in the expression of

,

Therefore,

On the other hand, analyzing the error terms from previously derived estimates, it can be deduced that,

Hence, (

34) follows. Moreover, since the leading term

is positive for

, thus it implies that

is positive for large

x, and the proof is complete. □

Remark 4.2.

We can rephrase Theorem (4.1) by claiming that, for every ,

for sufficiently large x.

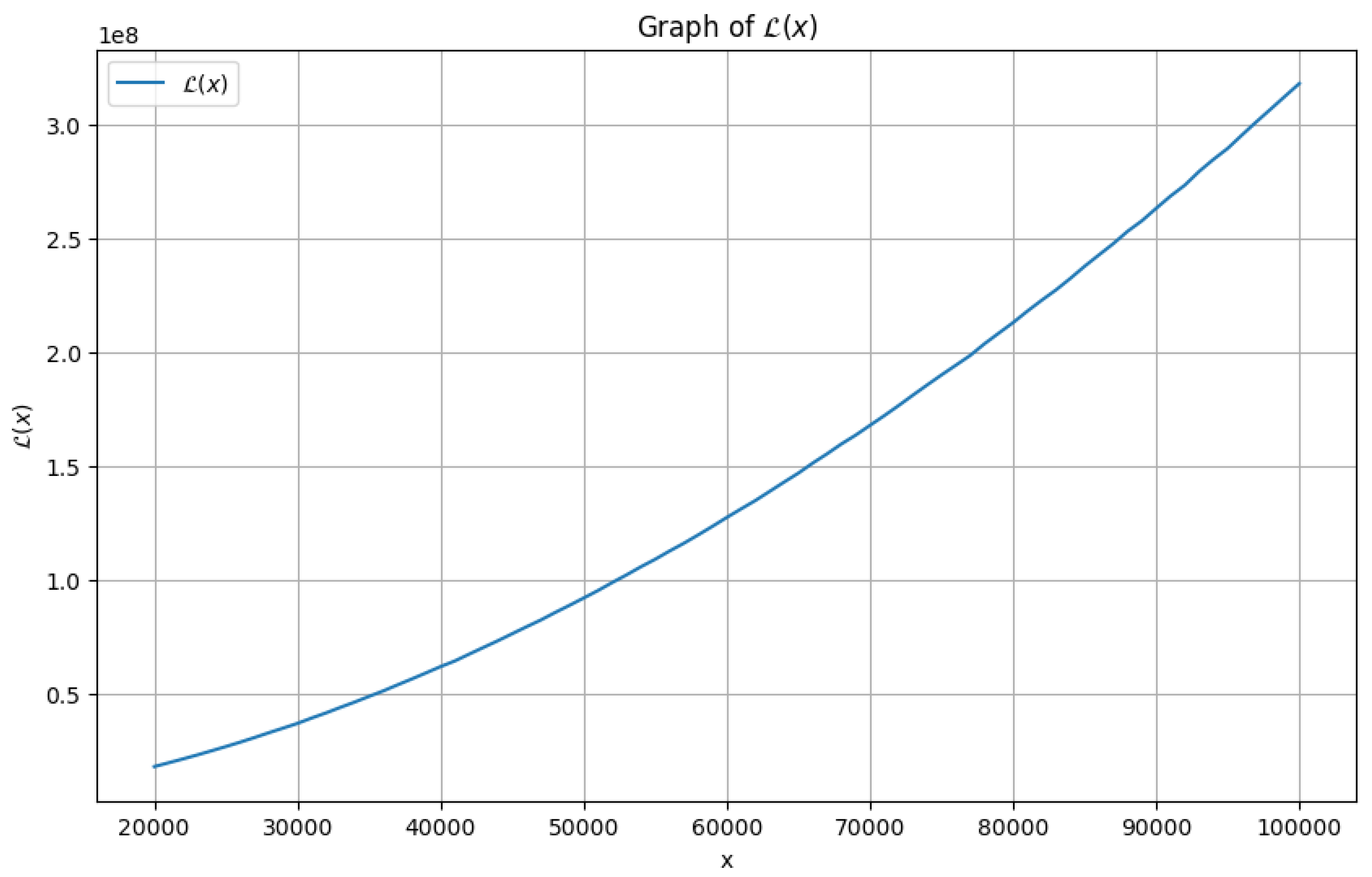

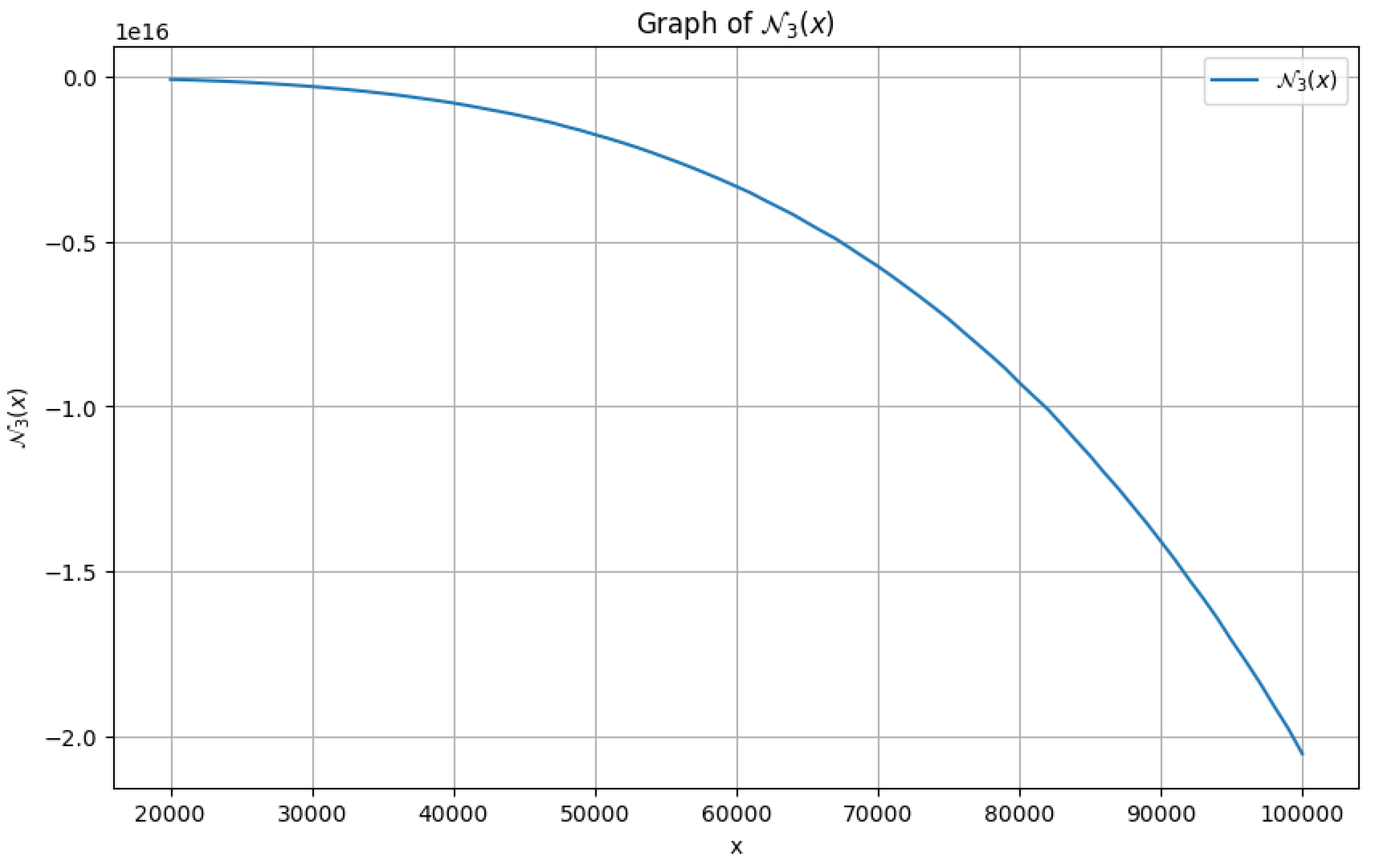

4.2. Numerical Estimates for

For a specific scenario when

, plotting

as compared to

x using

PYTHON programming language

1 gives us the following graph as in

Figure 3 for

. Moreover, applying

MATHEMATICA1, it can be asserted using the data shown in

Table 3 in the range,

that,

is indeed

increasing. As a result, the statement (

42) can be properly accepted.

4.3. Logarithmic Weighted Sum Inequality

It is very much possible to improve (

34) even further, where one can also consider the case which involves

logarithmic weights.

Theorem 4.3.

The following can in fact be conjectured for the logarithmic weights,

Then,

And, for large values of x.

Proof. A priori for large

x, utilizing (

3) (cf. [

4]),

Rigorously computation each and every term of

yields,

and similarly,

Subsequently squaring the left-hand side of (

45),

Using the

Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality, and considering the main term and error terms separately,

Where,

denotes the

Harmonic Number. Using the harmonic series approximation,

Hence, from (

47),

As for the error term,

Thus, combining all our deductions,

Furthermore, for the second term in (

43), we have the following calculations,

Approximating the main term,

Using the harmonic series approximation,

As a consequence,

Combining all,

Considering the dominant term. As a result, we conclude,

for large

x, and moreover, the dominant term,

being always positive for

, we can thus assert that,

for sufficiently large values of

x. □

Remark 4.4.

We can reaffirm Theorem (4.3) in the following manner. For any ,

for sufficiently large values of x.

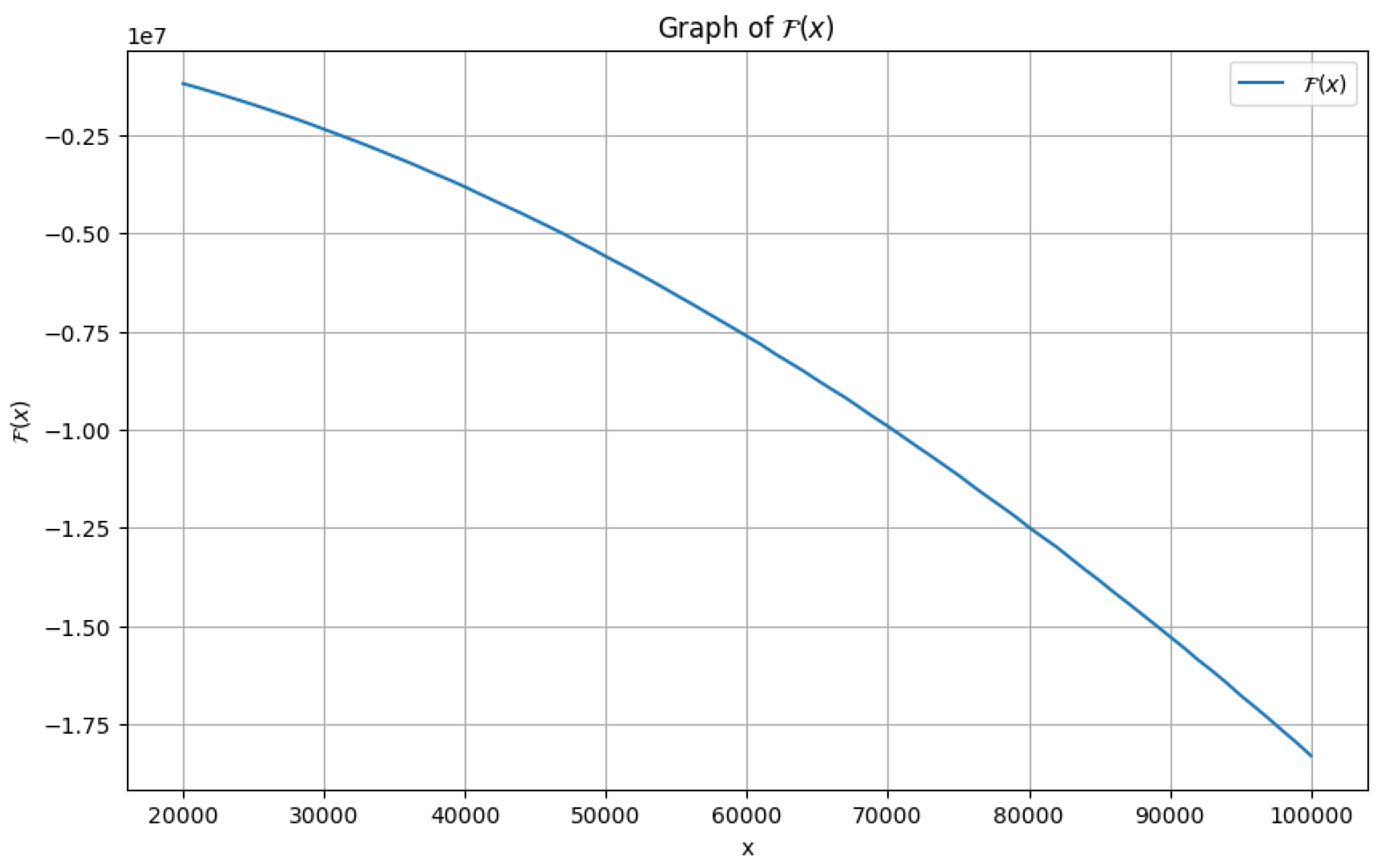

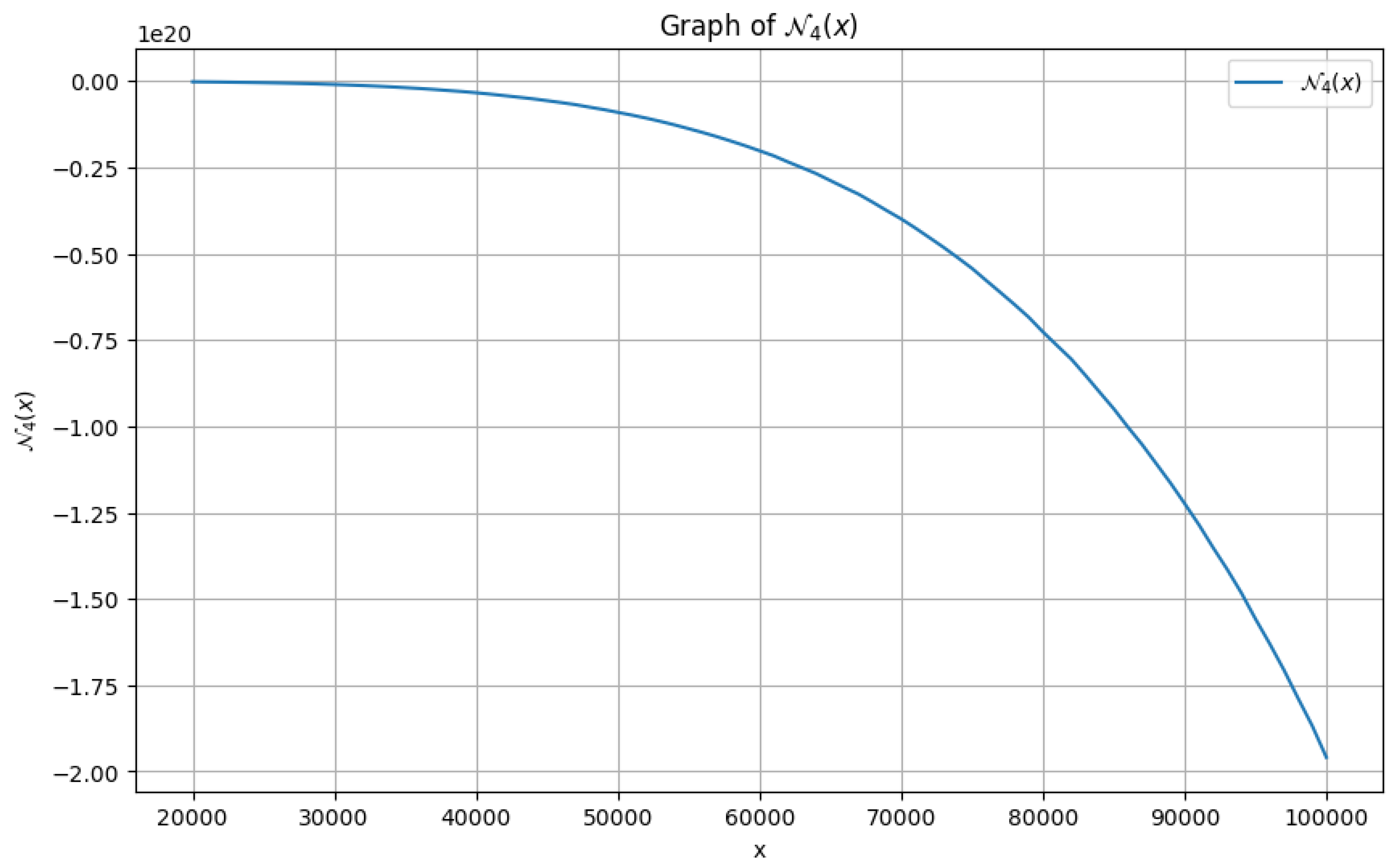

4.4. Numerical Estimates for

Similarly as in other cases,

PYTHON programming language

1 can in fact be applied in order to observe the plot of

as compared to

x. The following

Figure 4 shows the graph for

and considering

.

In addition to above, with the help of

MATHEMATICA1, it can be observed in

Table 4 that,

is in fact

decreasing in the range,

. As a result, the statement (

51) can also be numerically verified for large values of

x.

5. A More General Framework

Given the asymptotic nature of the prime counting function

, the general form of such polynomial functions can be formulated as follows.

where

P and

Q are polynomials and

R is a term that compensates for higher-order error terms. Subsequently, one can claim that, the error term in (

52) might behave similarly as in the previous cases. In mathematical terms, it might very well be possible that,

for some degree

d depending on the degrees of

P and

Q.

In order to justify our claim (

53) corresponding to (

52), let’s delve into a specific example by explicitly choosing polynomials

P,

Q, and

and studying the function

for different cases explicitely.

5.1. A Typical Example I : Generalized Cubic Polynomial Inequality

We assume,

and,

for every

. Then, in contrast to what we’ve discussed in Theorem (3.1), we can observe a significant change in the behaviour of the so-called

Generalized Cubic Polynomial defined as,

Furthermore, one has the following estimate for

as

x increases.

Theorem 5.1.

A priori defined as in (54) for every , we can derive that,

Furthermore, for sufficiently large values of x.

Proof. Utilizing (

4) in Theorem (2.2) as we’ve done in other cases, along with the derivations done in (

7) and (

8), we rigorously compute the following terms of

indivudually for large values of

n and

x,

and,

Substituting (

56), (

57) and (

58) back into

yields,

Important to note that, for sufficiently large

x, the dominant term on the R. H. S. of (

59) will be

. The other terms will have exponentially decaying factors due to the presence of

and

, making them small relative to the leading term. Therefore, the dominant term is positive, and the higher-order error terms do not affect the sign significantly.

In other words, the terms

and

on (

59) are small for large

x, the dominant term

ensures that

. Moreover, we have,

And thus the proof is complete.

□

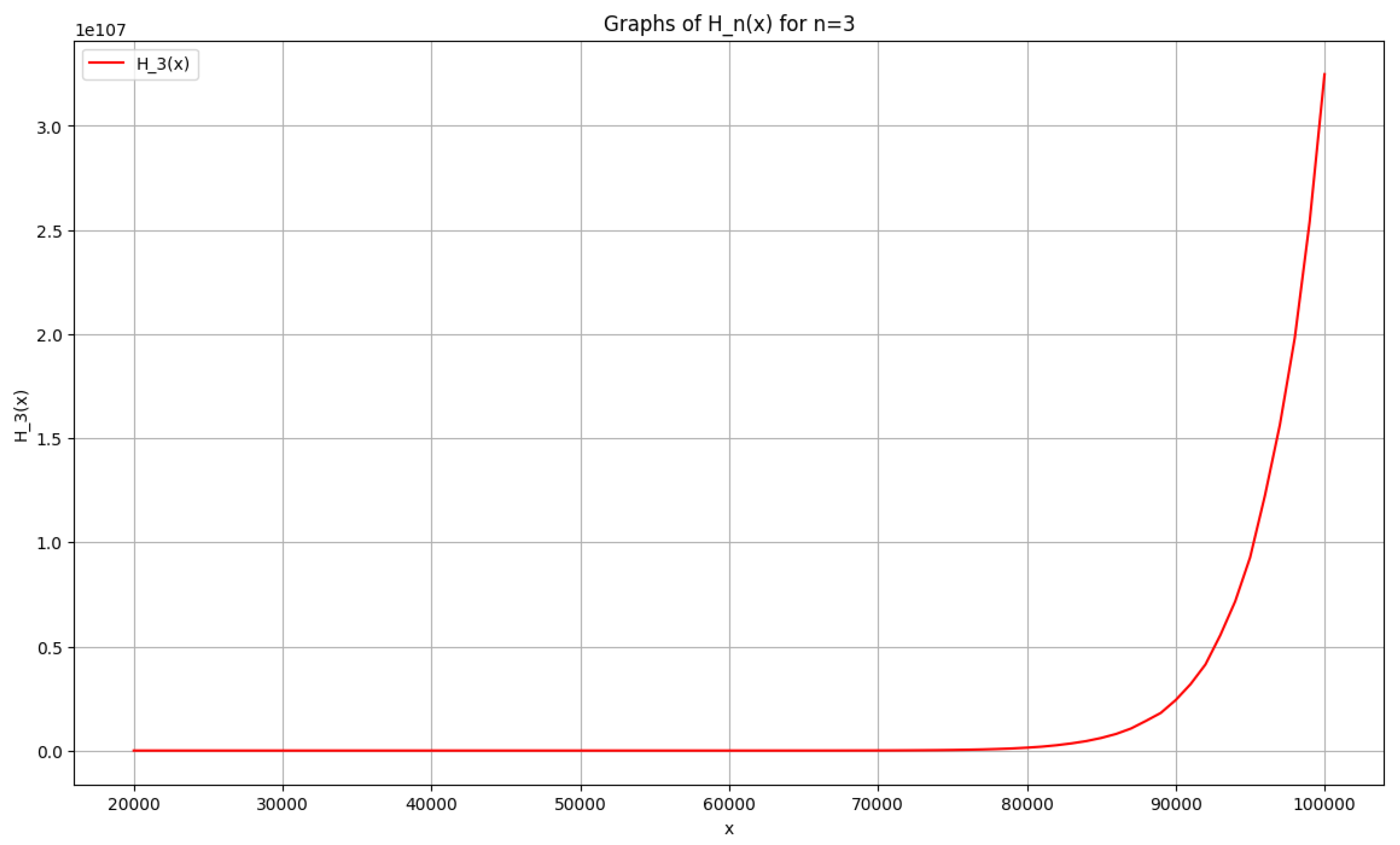

5.2. Numerical Estimates for

Applying

PYTHON programming language

1, we can in fact observe the plot of

(

) as compared to

x for some special cases respectively. (N.B. Ardent researchers are highly encouraged to study the same using any different values of

n) Subsequently,

Figure 1,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 represents the respective graphs for

.

Furthermore, using

MATHEMATICA1 it can be inferred from

Table 1 and

Table 5 that, unlike

(in this case,

is simply denoted by

as defined in (

5)) which is strictly monotone

decreasing,

and

are strictly monotone

increasing while

x assumes values in the range,

. As a result, it can surely be concluded that,

for sufficiently large

x and for

, having an exception for

.

Again, choosing P, Q and R accordingly, we can indeed conjecture a certain generalization of the Weighted Sum Inequality (cf. Theorem (4.1)).

5.3. A Typical Example II : Generalized Weighted Sum Inequality

For some fixed

, consider the polynomials,

To maintain symmetry and include higher-order error terms, we choose

. It can be observed that, degrees of each of the polynomials

P,

Q and

R are the same

(

). We study the polynomial,

under two circumstances separately.

5.3.1. deg(P), deg(Q) and deg(R) Are Odd

We assume,

, for any positive integer

m. A priori from the approximations derived in (

3) and (

4) (cf. [

4]), we substitute

,

and

in them to compute each and every term in the polynomial separately.

Using the harmonic series approximation (

48).

For the second term in

,

Finally, for

,

Combining (

62), (

63) and (

64),

Subsequently, the dominant error term in

can be found as,

5.3.2. deg(P), deg(Q) and deg(R) Are Even

In this case, we assume,

, for any positive integer

m. Similarly, as in the first case, we utilize the approximations deduced in (

3) and (

4) (cf. [

4]), we substitute

,

and

in them to approximate each and every term in the polynomial individually. From (

61),

Moreover, for the second term in

,

Finally, for

,

Combining (

66), (

67) and (

68),

Important to assess that, the dominant error term in

is,

In conclusion, in both the cases, we can properly justify in this example that, (

53) is definitely satisfied. Moreover, as for the sign of

, it can be duly noted that, the main term excluding the error term is indeed negative for sufficiently large values of

x. Thus, in this scenario, one can safely conclude the following.

Theorem 5.2.

Given the weighted sum of Prime Counting Function over small intervals,

where, , the following holds true for sufficiently large values of x.

5.4. Numerical Estimates for

A priori with the help of

PYTHON programming language

1 we can indeed study the plot of

(

) and

(

) as compared to

x for the odd and even cases respectively. (N.B. These two are some special cases for chosen values of

m, one can study the same if interested using any different values of

m) Subsequently,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 represents the respective graphs for

and considering

.

Furthermore, utilizing

MATHEMATICA1, it can be inferred from

Table 6 that,

and

are strictly monotone

decreasing while

x assumes values in the range,

. As a result, it can surely be concluded that,

for sufficiently large

x, and for this particular example, i.e. for this particular choice of

P,

Q and

R.

6. Furture Scope for Research

It can definitely be said that, the results discussed in this article serves as a mere small version of what can be considered as a plethora of possibilities that future researchers can come up with.

It is very much possible to eventually derive a similar estimate for polynomials of degree in , adopting similar techniques as devised in proposing the Cubic Polynomial Inequality and the Higher Degree Polynomial Inequality. It may very well help us to establish certain conjectures and even extend the study of primes even further.

Regarding the estimates which we’ve derived for functions involving weighted sums of over small intervals, it might be interesting to study them even further by varying indivudual weights of such funtions, and study their respective sign changes over increasing values of x.

On the other hand, it is very much possible to produce absolutely new results from the general polynomial (

52), by choosing

P,

Q and

R appropriately. As evident from the two examples which serves as generalizations of two of the inequalities which we’ve already discussed, it’s fascinating to observe that, the sign changes of the polynomials are completely unpredictable. For example, we’ve deduced that, for higher values of

x, the generalized cubic polynomial

as defined in (

54) yields negative values for

(in this case, we denote

by

, as defined in (

5)), whereas, it’s sign reverses drastically for the case,

(cf. Theorem (5.1)). Important to mention that, different conclusions may very well be possible for different types of examples. Although each and every such result involves some robust calculations and numerical computations, but it eventually opens up a whole new area for future researchers to explore, which might end up in enlightening us to some significant discoveries in the relevant field of Number Theory.

Data Availability Statement

I as the sole author of this article confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

I’ll always be grateful to Prof. Adrian W. Dudek ( Adjunct Associate Professor, Department of Mathematics and Physics, University of Queensland, Australia ) for inspiring me to work on this problem and pursue research in this topic. His leading publications in this area helped me immensely in detailed understanding of the essential concepts.

Conflicts of Interest

I as the author of this article declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ramanujan Aiyangar, Srinivasa, Berndt, Bruce C, Ramanujan’s Notebooks: Part IV, New York: Springer-Verlag, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Dudek, Adrian W., Platt, David J., On Solving a Curious Inequality of Ramanujan, Experimental Mathematics, 2015, 24:3, 289-294. [CrossRef]

- Titchmarsh, E. C., The Theory of the Riemann Zeta-function, Oxford University Press, 1951. Second edition revised by D. R. Heath-Brown, published by Oxford University Press, 1986. [CrossRef]

- De, Subham, "On proving an Inequality of Ramanujan using Explicit Order Estimates for the Mertens Function", arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.12052 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, L., Sharper bounds for the Chebyshev Functions θ(x) and ψ(x). II, Mathematics of Computation, vol. 30, no. 134, pp. 337-360. [CrossRef]

- ngham, A. E., The distribution of prime numbers, Cambridge University Press, 1932. Reprinted by Stechert-Hafner, 1964, and (with a foreword by R. C. Vaughan) by Cambridge University Press, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Hassani, Mehdi, Remarks on Ramanujan’s Inequality Concerning the Prime Counting Function, Communications in Mathematics, Volume 29 (2021), Issue 3, Pages 473–482. [CrossRef]

- Hassani, Mehdi, Generalizations of an inequality of Ramanujan concerning prime counting function, Appl. Math. E-Notes 13 (2013) 148-154.

- Jameson, G.J.O., The Prime Number Theorem, Cambridge ; New York : Cambridge University Press, London Mathematical Society student texts, Vol. 53, 2003. [CrossRef]

- De, Subham, On the proof of the Prime Number Theorem using Order Estimates for the Chebyshev Theta Function, International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), Vol. 12 Issue 11, Nov. 2023, pp. 1677-1691. [CrossRef]

- Hassani, Mehdi, “On an Inequality of Ramanujan Concerning the Prime Counting Function”, Ramanujan Journal 28 (2012), 435–442. [CrossRef]

- Ramanujan, S, “Collected Papers”, Chelsea, New York, 1962.

- Hardy, G. H., A formula of Ramanujan in the theory of primes, 1. London Math. Soc. 12 (1937), 94-98. [CrossRef]

- Hardy, G. H., Collected Papers, vol. II, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1967.

- Axler, Christian, On Ramanujan’s prime counting inequality, arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.02486 (2022). arXiv:2207.02486 (2022).

- Mossinghoff, M. J., Trudgian, T. S., Nonnegative Trigonometric Polynomials and a Zero-Free Region for the Riemann Zeta-Function, arXiv: 1410.3926, 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).