2.1. A Simple Spherical Accretion Model

This model is unphysical because it considers the interaction between matter and radiation but only in dynamical terms, ignoring that the radiation is absorbed by the infalling matter. As written, its utility comes from the fact that the equation of motion can be solved analytically.

A particle of mass

m falling from a radius

experiences two forces: i) the gravitational force

down to the surface radius

R that we suppose much smaller than

; and 2) the radiation pressure due to Thomson scattering. In the classical treatment of radiation [

1], the radiation momentum is completely absorbed by matter at a rate

where

W is the energy density of the electromagnetic field and

is the Thomson cross section. Since

depends on the inverse of the square of the particle mass, this force acts mainly on the electrons. On the contrary, the gravitational force is larger for protons: as a consequence the flow should be treated as a two fluids plasma but assuming that we have only fully ionized hydrogen, we can treat the problem as one single fluid. In fact, the electric field arising from the interactions between protons and electrons keeps the two components coupled [

10]. The force acting on each particle is then

where

is the intensity field and

c is the light speed.

Depending on how we define the accretion luminosity, the equation of motion can be written in two different ways:

where

m is the proton mass and, when ignoring absorption, we can set

.

Equation (

4) follows immediately from Equation (

5) if the condition

is imposed. However, it should be noted that

means that the velocity is constant, not necessarily that

everywhere, so that we have to verify that

is indeed an allowed solution.

The problem is that if

, clearly

as well: the condition

, through Equation (

2), implies

and, at same time, implies that

. Thus, the combination of Equation (5) and Equation (

2) does not admit the solution

. The inconsistency comes from what has been already said: Equation (

2) is valid only for matter in free fall and this is not the case. The only conclusion we can draw from setting

in Equation (5) is that

.

If we adopt Equation (

1) and solve Equation (6), it is immediate to derive

from which

with

. Thus

where

is the final velocity for matter in free-fall: as expected,

when

. The solution

is acceptable asymptotically, it is approached as

.

By combining Equation (

1) with Equation (

9), after some algebra one derives

showing that

, like

, is asymptotically reached for

.

In this way we can see that increasing increases as well. But taking into account the negative feedback of the radiation pressure, that is feeded by the gravitational potential well, the increase in luminosity does not scale linearly with .

2.1.1. The Case

In Equation (6), the luminosity produced internally by the accreting source, named in the following , has been assumed to be zero. In case , the equations change but the final result is, qualitatively, not different from the previous case, provided that .

Equation (6) becomes

with

; Equation (8) is now

and

so that

Thus, accretion is still possible with any provided that . When , the radiation pressure due to that clearly does not depend on , stops accretion.

The accretion luminosity is easily derived:

with

for

.

2.2. A More Realistic Accretion Model

In the previous section we have seen the consequences of defining the accretion luminosity following Equation (

1) or Equation (

2), by using a simple model. This model is based on three assumptions: i) zero-temperature flow, so that no interaction between particles is taken into account; ii) no energy exchange between matter and radiation; iii)

decreases with radius only by the geometrical factor

, which implies a constant otpical depth

at all radii.

Now, assumption i) makes the model not too much realistic even if not unphysical. But assumptions ii) and iii) are not consistent with the fact that the interaction between radiation and matter must happen in order to justify the equation of motion given either by Equation (5) or by Equation (6).

Now, assumption i) makes the model not too much realistic even if not unphysical. But assumptions ii) and iii) are not consistent with the fact that the interaction between radiation and matter must happen in order to justify the equation of motion given either by Equation (5) or by Equation (6).

In this section, thus, I will employ a more realistic accretion model. In literature one can find accurate accretion models that describe the physics of the accretion process, e.g., Fukue [

11] or Murakami et al. [

12], just to make a few of examples. Adapting these models to my needs, however, is not simple because in many cases the use of Equation (

2) is not written explicitly, so that it is not immediate to find out how to modify a given model to adopt Equation (

1). And, as I am going to show, it can happen that Equation (

2) and Equation (

1) are unintentionally adopted at the same time.

For these reasons, I use a model developed fifty years ago by Maraschi et al. [

13], MTR in the following, that while considering the exchange between matter and radiation, so assumption ii) above is no longer present, it is still quite simple.

The set of equations used by MRT is:

where the multiplying 4/3 factor in front of

was added by Kafka and Mészáros [

14]; note also that I have assumed a negative velocity, so the sign in the continuity equation and in the term

is opposite to MRT’s set.

Equation (18) gives

where the constant

is found assuming that particles’ energy goes to zero as

. Now, if we analyze carefully Equation (20), we will see that it implies Equation (

1) even if MTR assumed explicitly that Equation (

2) holds. In fact, Energy

E is given by

while the accretion luminosity is

; for

we have

so that, in MTR’s model there is the hidden adoption of Equation (

1). Of course, if one assumes that

, that is, that the final velocity is equal to the free-fall final velocity, the two formulations of

give the same result. But MRT derived for their model the velocity profile

, finding that for any

, it is always

, which is expected. Then we have

which shows that MTR’s model was not internally consistent. Of course, my aim is not to show the inconsistency of MTR’s work, I make these considerations only to explain why I adopt a simple model instead of a complex and much more realistic, accretion model. Only in this way I can go deep in the physics of the solution to read behind the lines what are all the assumptions, intentionally or not, of the model.

Now, for

we have

where the equal sign holds when

for

. By comparing Equation (23) with Equation (24), we have to conclude either that two equations are not consistent, or that

increase with

r, which looks unphysical. The reason of the inconsistency comes from neglecting the absorption of the radiation, but this problem becomes evident only if Equation (

1) is assumed, because with Equation (

2) it is clear that

.

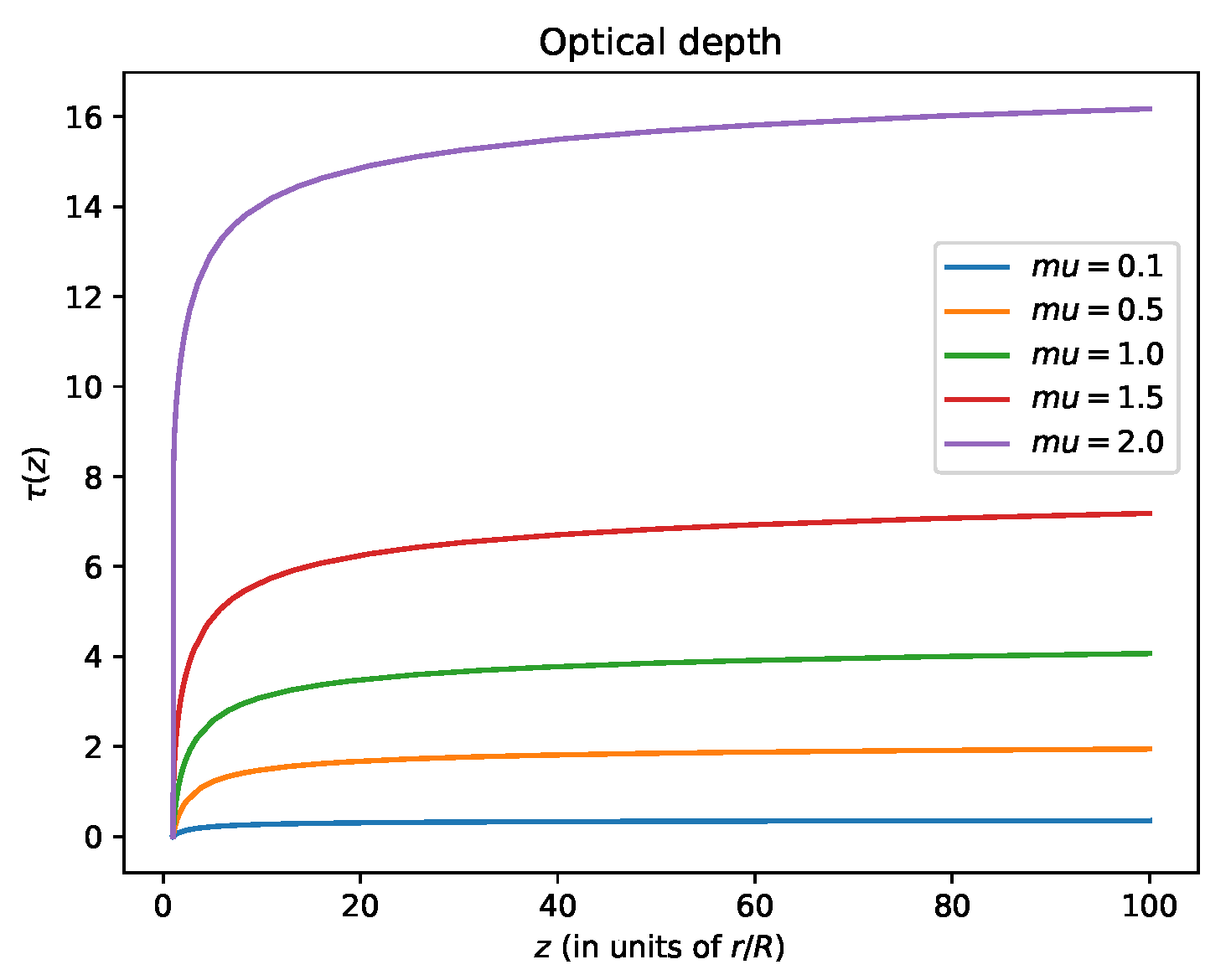

The set of Equations (17) — (19) cannot be solved under the assumption iii) (i.e.,

, see the beginning of this section). We have to take into account the absorption of the radiation by writing

with

( will be used later on in this section).

By combining the different equations, it is possible to arrive to a second order differential equation in

v: all the steps are detailed in Appendix A where the general case

is treated. Here I present the final equation for the case

:

with

,

and, for typical neutron stars,

so that Equation (26) becomes

with

because

.

When

Equation (27) turns into

and it is easy to verify that the free-fall velocity

is a solution.

Let’s now see if a solution

, say

(no force), is possible. Equation (27) becomes

A constant solution, by definition, must be valid for any

z, in particular also for

where the previous equation simplifies in

from which

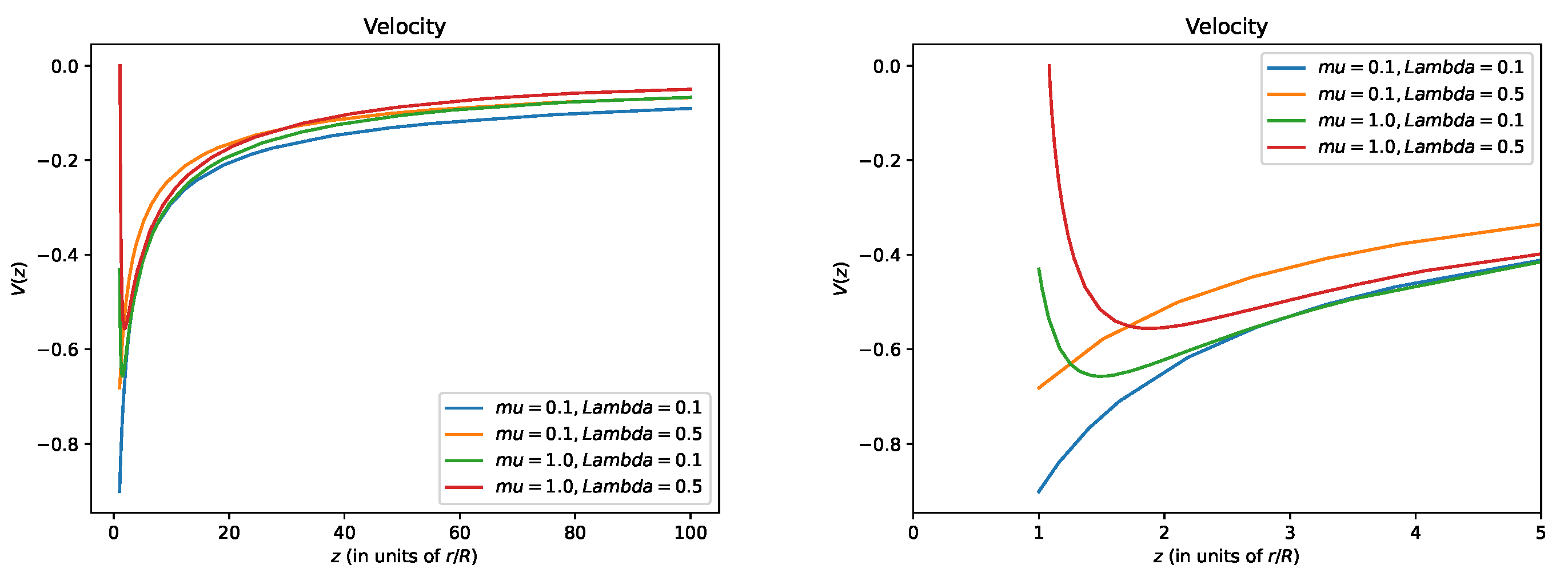

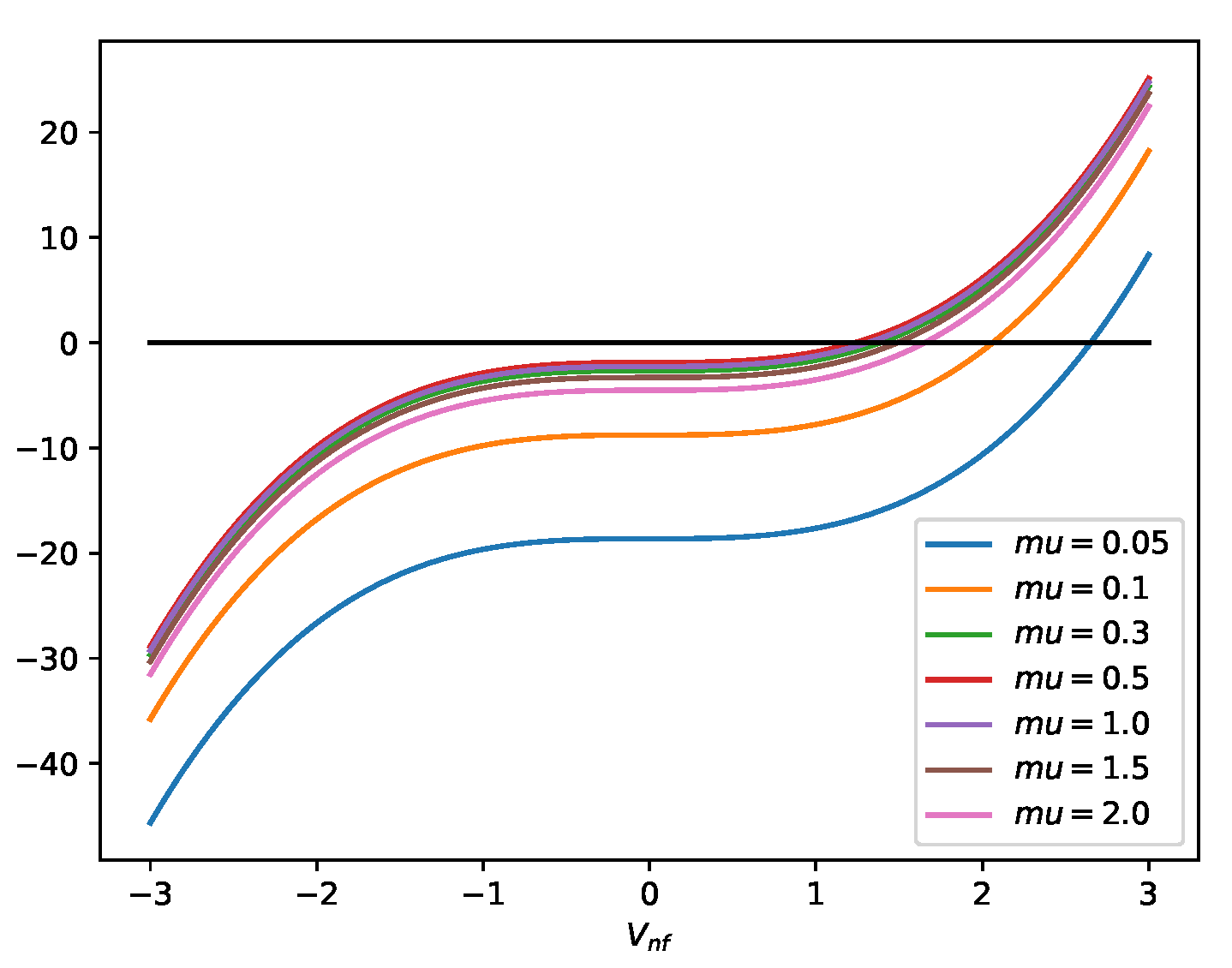

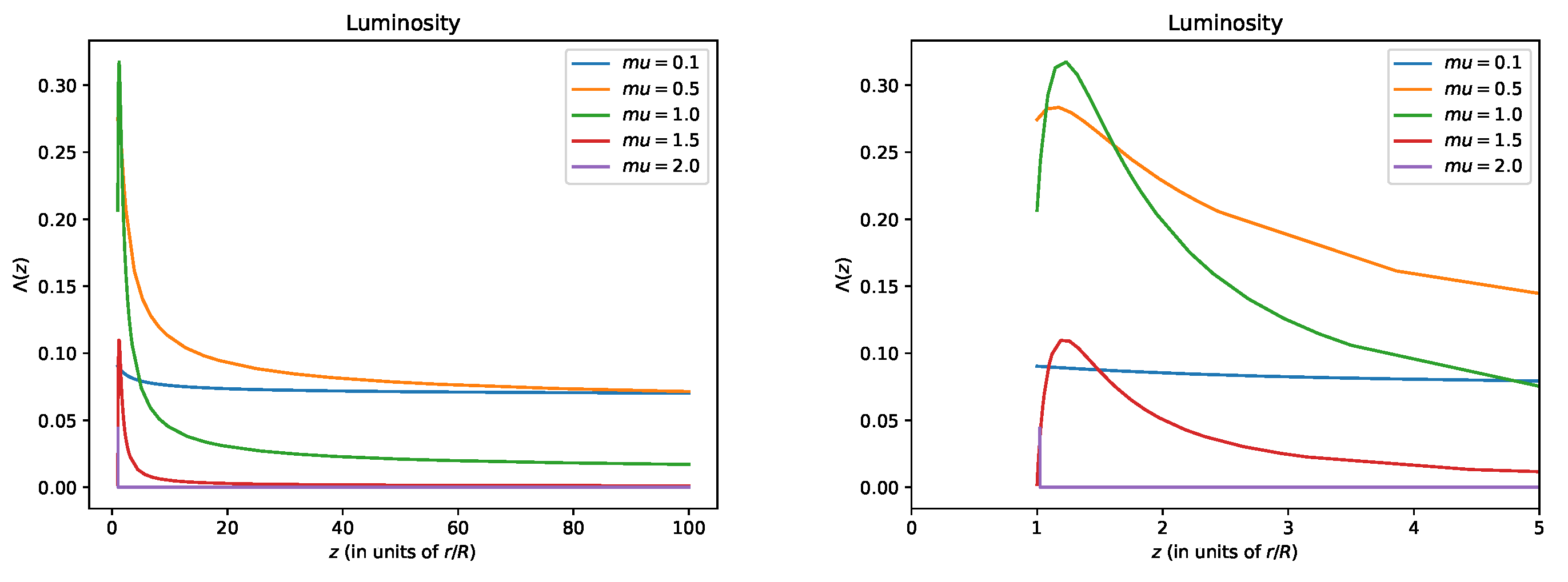

It is convenient to plot this cubic equation to look for the solutions: this is done in

Figure 1 for a set of values of

. The case

is not shown because it corresponds to matter in free fall and

V cannot be constant; for

, a curve not shown in the figure, a solution for

is not found because the curve, in the range shown, never intersects the line

. A value of

that is solution of the cubic equation starts appearing somewhere in the range

. But for

, the range of values explored in the next section, Equation (27) admits only

, so that

is not acceptable: as a consequence, Equation (27) does not admit a solution

and, in turn, this means that the total force acting on each particle can never be zero.