Submitted:

15 July 2024

Posted:

16 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

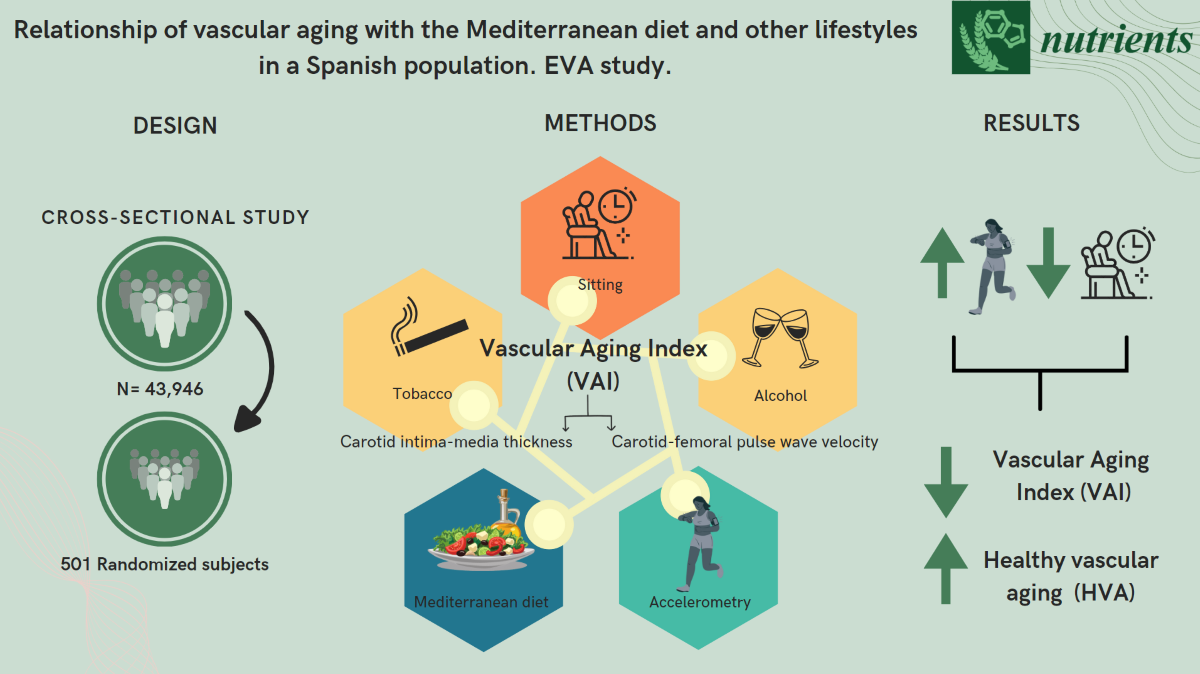

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

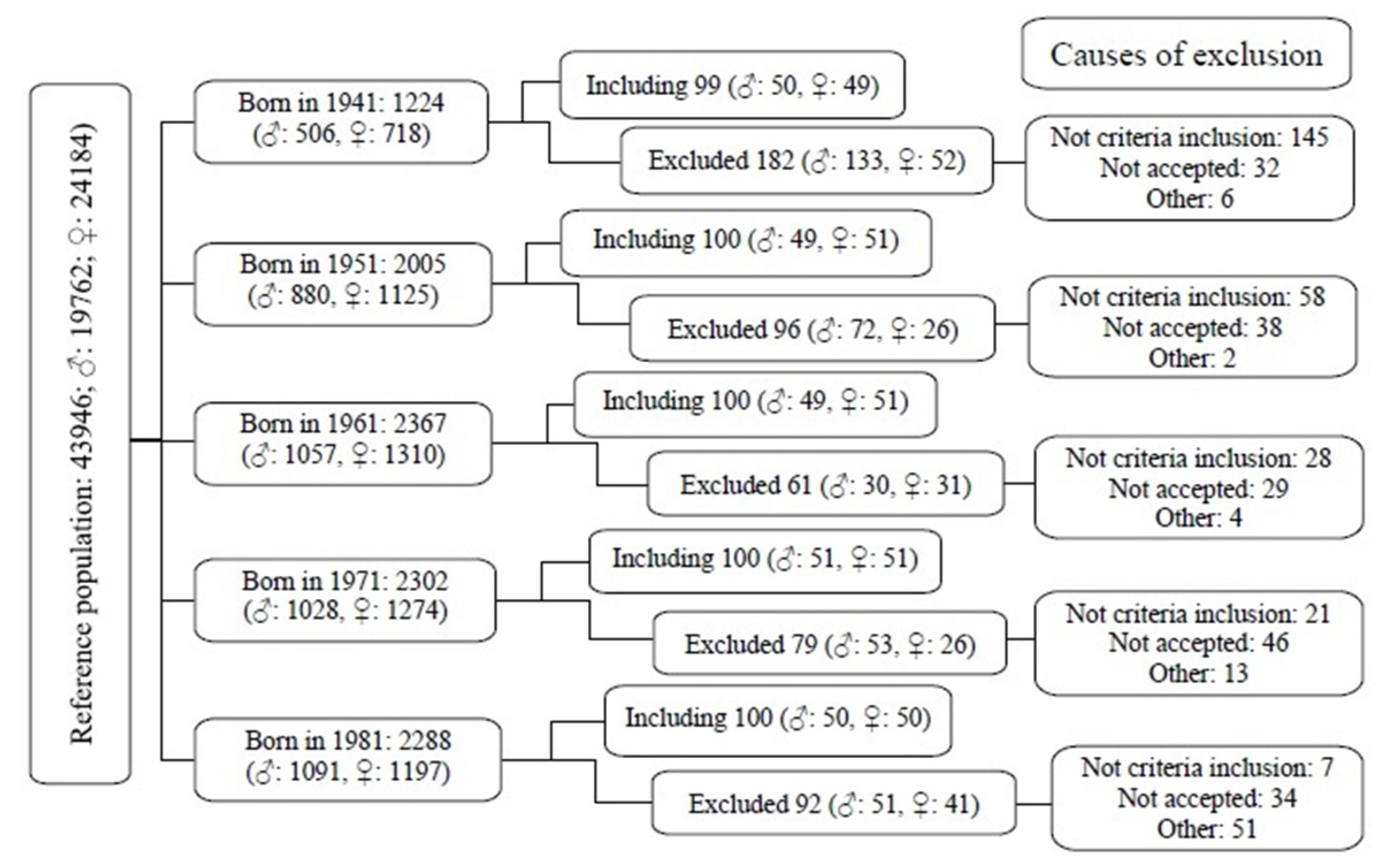

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Variables and Measuring Instruments

2.3.1. Healthy Lifestyles

2.3.1.1. Mediterranean Diet

2.3.1.2. Alcohol and Smoking

2.3.1.3. Physical Activity and Sedentary Time

2.3.2. Assessment of Vascular Structure, Function and Vascular Aging

2.3.2.4 Vascular Aging Index (VAI)

2.3.3. Definition of Healthy Vascular Aging

2.3.4. Anthropometric Measurements and Cardiovascular Risk Factors

2.3.5. Analytical Tests

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Principles

3. Results

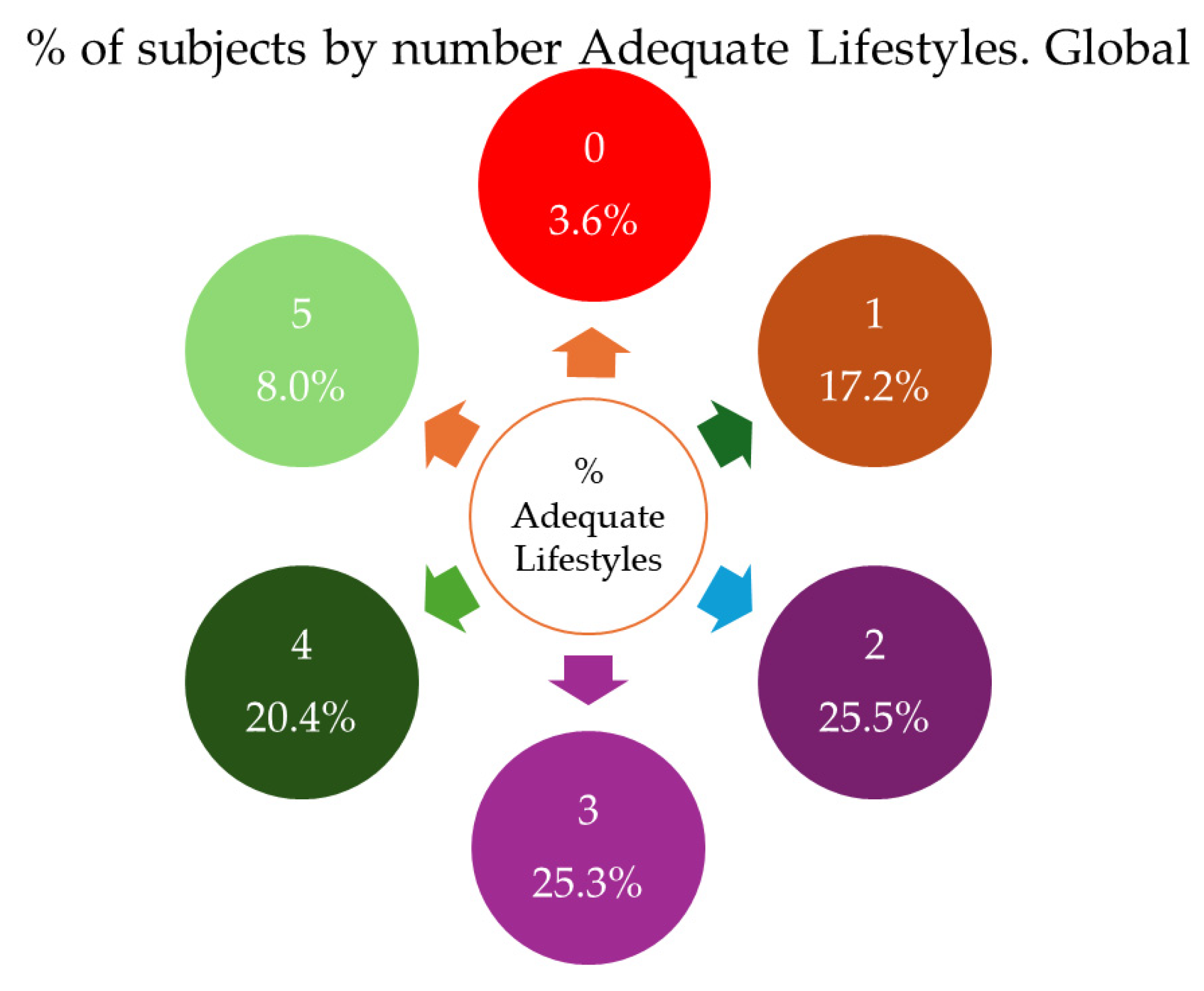

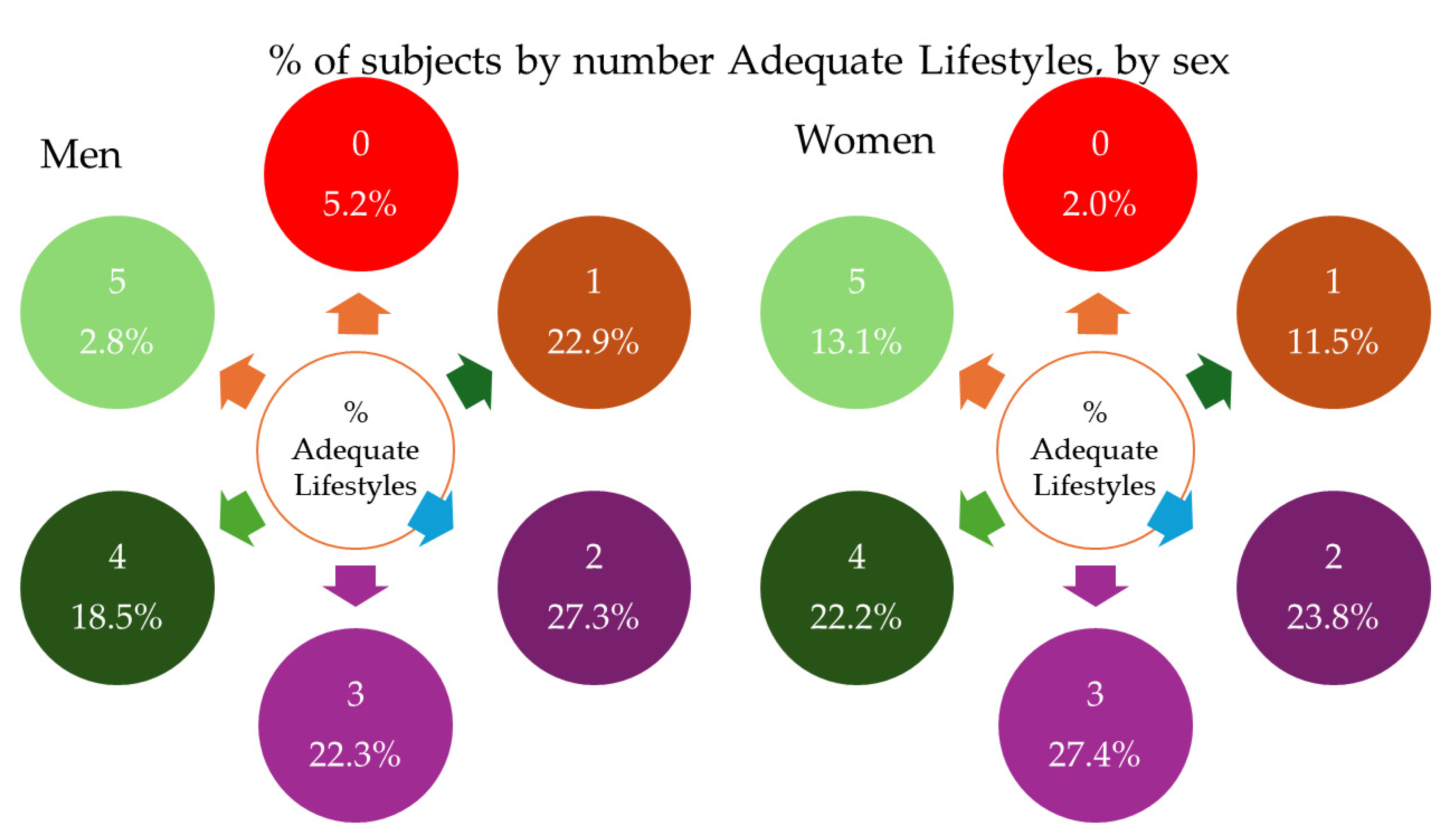

3.1. Lifestyles, Risk Factors, and Vascular Structure and Function of the Subjects Included, Overall and by Sex

3.2. Lifestyles, Risk Factors, and Vascular Structure and Function According to Vascular Aging

3.3. Correlation of Vascular Aging with Mediterranean Diet and Other Lifestyles

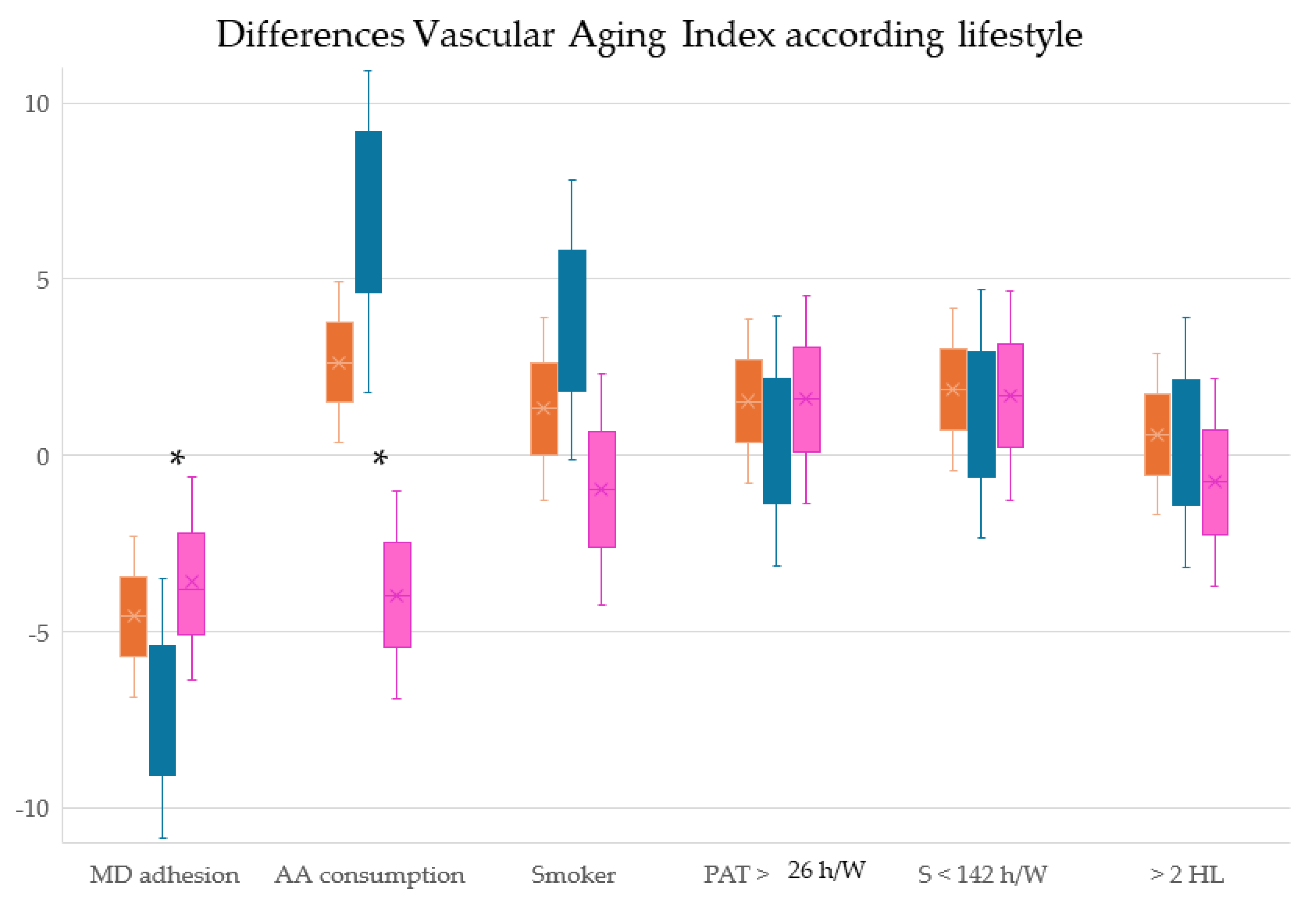

3.4. Association between Vascular Aging Index and Healthy Lifestyles, Multiple Regression Analysis

3.5. Association between Vascular Aging Index and Healthy Lifestyles, Logistic Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitchell, E.; Walker, R. Global ageing: successes, challenges and opportunities. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2020, 81, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, K.L.; Clayton, Z.S.; DuBose, L.E.; Rosenberry, R.; Seals, D.R. Effects of regular exercise on vascular function with aging: Does sex matter? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2024, 326, H123–h137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P.; Cunha, P.G.; Lacolley, P.; Nilsson, P.M. Concept of Extremes in Vascular Aging. Hypertension 2019, 74, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, K.L.; Rossman, M.J.; Chonchol, M.; Seals, D.R. Strategies for Achieving Healthy Vascular Aging. Hypertension 2018, 71, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, Z.S.; Craighead, D.H.; Darvish, S.; Coppock, M.; Ludwig, K.R.; Brunt, V.E.; Seals, D.R.; Rossman, M.J. Promoting healthy cardiovascular aging: emerging topics. J Cardiovasc Aging 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, S. Defining vascular aging and cardiovascular risk. J Hypertens 2012, 30 Suppl, S3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R.M.; Nilsson, P.M.; Engström, G.; Wadström, B.N.; Empana, J.P.; Boutouyrie, P.; Laurent, S. Early and Supernormal Vascular Aging: Clinical Characteristics and Association With Incident Cardiovascular Events. Hypertension 2020, 76, 1616–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson Wadström, B.; Fatehali, A.H.; Engström, G.; Nilsson, P.M. A Vascular Aging Index as Independent Predictor of Cardiovascular Events and Total Mortality in an Elderly Urban Population. Angiology 2019, 70, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Sanchez, M.; Gomez-Sanchez, L.; Patino-Alonso, M.C.; Cunha, P.G.; Recio-Rodriguez, J.I.; Alonso-Dominguez, R.; Sanchez-Aguadero, N.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, E.; Maderuelo-Fernandez, J.A.; Garcia-Ortiz, L.; et al. Vascular aging and its relationship with lifestyles and other risk factors in the general Spanish population: Early Vascular Ageing Study. J Hypertens 2020, 38, 1110–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Qi, L.; Xu, L.; Sun, X.; Liu, W.; Zhou, S.; van de Vosse, F.; Greenwald, S.E. Effects of exercise modalities on central hemodynamics, arterial stiffness and cardiac function in cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0200829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, K.O.; Mahoney, S.A.; Venkatasubramanian, R.; Seals, D.R.; Clayton, Z.S. Aging, aerobic exercise, and cardiovascular health: Barriers, alternative strategies and future directions. Exp Gerontol 2023, 173, 112105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska-Newton, A.M.; Stoner, L.; Meyer, M.L. Determinants of Vascular Age: An Epidemiological Perspective. Clin Chem 2019, 65, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appiah, D.; Capistrant, B.D. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment in the United States and Low- and Middle-Income Countries Using Predicted Heart/Vascular Age. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 16673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P.; Cunha, P.G.; Lacolley, P.; Nilsson, P.M. Concept of Extremes in Vascular Aging. Hypertension 2019, HYPERTENSIONAHA11912655. [CrossRef]

- Niiranen, T.J.; Lyass, A.; Larson, M.G.; Hamburg, N.M.; Benjamin, E.J.; Mitchell, G.F.; Vasan, R.S. Prevalence, Correlates, and Prognosis of Healthy Vascular Aging in a Western Community-Dwelling Cohort: The Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension 2017, 70, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, G.C.; Jackson, R.E.; Reis, J.; Román, A.N.; Toledo, J.B.; Toledo, E. Extra-virgin olive oil for potential prevention of Alzheimer disease. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2019, 175, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, D. Health Benefits of Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddoumi, A.; Denney, T.S., Jr.; Deshpande, G.; Robinson, J.L.; Beyers, R.J.; Redden, D.T.; Praticò, D.; Kyriakides, T.C.; Lu, B.; Kirby, A.N. , et al. Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Enhances the Blood-Brain Barrier Function in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, K.; Takeda, A.; Martin, N.; Ellis, L.; Wijesekara, D.; Vepa, A.; Das, A.; Hartley, L.; Stranges, S. Mediterranean-Style Diet for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Cochrane Review. Glob Heart 2020, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentella, M.C.; Scaldaferri, F.; Ricci, C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Miggiano, G.A.D. Cancer and Mediterranean Diet: A Review. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekete, M.; Szarvas, Z.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Feher, A.; Csipo, T.; Forrai, J.; Dosa, N.; Peterfi, A.; Lehoczki, A.; Tarantini, S. , et al. Nutrition Strategies Promoting Healthy Aging: From Improvement of Cardiovascular and Brain Health to Prevention of Age-Associated Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Peláez, S.; Fito, M.; Castaner, O. Mediterranean Diet Effects on Type 2 Diabetes Prevention, Disease Progression, and Related Mechanisms. A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Di Bella, G.; Cusumano, C.; Parisi, A.; Tagliaferri, F.; Ciriminna, S.; Barbagallo, M. Mediterranean diet in the management and prevention of obesity. Exp Gerontol 2023, 174, 112121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, K.; Takeda, A.; Martin, N.; Ellis, L.; Wijesekara, D.; Vepa, A.; Das, A.; Hartley, L.; Stranges, S. Mediterranean-style diet for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019, 3, CD009825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, K.; Takeda, A.; Martin, N.; Ellis, L.; Wijesekara, D.; Vepa, A.; Das, A.; Hartley, L.; Stranges, S. Mediterranean-style diet for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019, 3, Cd009825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreo-López, M.C.; Contreras-Bolívar, V.; Muñoz-Torres, M.; García-Fontana, B.; García-Fontana, C. Influence of the Mediterranean Diet on Healthy Aging. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, E.; Ferro, Y.; Pujia, R.; Mare, R.; Maurotti, S.; Montalcini, T.; Pujia, A. Mediterranean Diet In Healthy Aging. J Nutr Health Aging 2021, 25, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Di Bella, G.; Veronese, N.; Barbagallo, M. Impact of Mediterranean Diet on Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and Longevity. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Innocenzo, S.; Biagi, C.; Lanari, M. Obesity and the Mediterranean Diet: A Review of Evidence of the Role and Sustainability of the Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Román-Viñas, B.; Sanchez-Villegas, A.; Guasch-Ferré, M.; Corella, D.; La Vecchia, C. Benefits of the Mediterranean diet: Epidemiological and molecular aspects. Mol Aspects Med 2019, 67, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohyama, Y.; Teixido-Tura, G.; Ambale-Venkatesh, B.; Noda, C.; Chugh, A.R.; Liu, C.Y.; Redheuil, A.; Stacey, R.B.; Dietz, H.; Gomes, A.S. , et al. Ten-year longitudinal change in aortic stiffness assessed by cardiac MRI in the second half of the human lifespan: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016, 17, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, L.; Mattace-Raso, F.U.; van Rosmalen, J.; van Rooij, F.; Hofman, A.; Franco, O.H. Effects of combined healthy lifestyle factors on functional vascular aging: the Rotterdam Study. J Hypertens 2016, 34, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.; Wassertheurer, S.; Hametner, B.; Moebus, S.; Pundt, N.; Mahabadi, A.A.; Roggenbuck, U.; Lehmann, N.; Jockel, K.H.; Erbel, R. Cross-sectional analysis of pulsatile hemodynamics across the adult life span: reference values, healthy and early vascular aging: the Heinz Nixdorf Recall and the MultiGeneration Study. J Hypertens 2019, 37, 2404–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Giorno, R.; Maddalena, A.; Bassetti, S.; Gabutti, L. Association between Alcohol Intake and Arterial Stiffness in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, D.; Britton, A.; Brunner, E.J.; Bell, S. Twenty-Five-Year Alcohol Consumption Trajectories and Their Association With Arterial Aging: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudnicka, E.; Napierała, P.; Podfigurna, A.; Męczekalski, B.; Smolarczyk, R.; Grymowicz, M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas 2020, 139, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Marcos, M.A.; Martinez-Salgado, C.; Gonzalez-Sarmiento, R.; Hernandez-Rivas, J.M.; Sanchez-Fernandez, P.L.; Recio-Rodriguez, J.I.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, E.; García-Ortiz, L. Association between different risk factors and vascular accelerated ageing (EVA study): study protocol for a cross-sectional, descriptive observational study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M. , et al. A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanidad, M.d. Límites de Consumo de Bajo Riesgo de Alcohol. Actualización del Riesgo Relacionado con los Niveles de Consumo de Alcohol, el Patrón de Consumo y el Tipo de Bebida. Ministerio de Sanidad Madrid, Spain: 2020.

- The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): a major international collaboration. WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators. J Clin Epidemiol 1988, 41, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melanson, E.L., Jr.; Freedson, P.S. Validity of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. (CSA) activity monitor. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1995, 27, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Marcos, M.A.; Recio-Rodríguez, J.I.; Patino-Alonso, M.C.; Agudo-Conde, C.; Gómez-Sanchez, L.; Gómez-Sanchez, M.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, E.; García-Ortiz, L. Protocol for measuring carotid intima-media thickness that best correlates with cardiovascular risk and target organ damage. Am J Hypertens 2012, 25, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.; Coca, A.; De Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A. , et al. 2018 Practice Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology: ESH/ESC Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens 2018, 36, 2284–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bortel, L.M.; Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P.; Chowienczyk, P.; Cruickshank, J.K.; De Backer, T.; Filipovsky, J.; Huybrechts, S.; Mattace-Raso, F.U.; Protogerou, A.D. , et al. Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens 2012, 30, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro Cáceres, A.; Navarro-Matías, E.; Gómez-Sánchez, M.; Tamayo-Morales, O.; Lugones-Sánchez, C.; González-Sánchez, S.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, E.; García-Ortiz, L.; Gómez-Sánchez, L.; Gómez-Marcos, M.A. , et al. Increase in Vascular Function Parameters According to Lifestyles in a Spanish Population without Previous Cardiovascular Disease-EVA Follow-Up Study. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi-Abhari, S.; Sabia, S.; Shipley, M.J.; Kivimäki, M.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Tabak, A.; McEniery, C.; Wilkinson, I.B.; Brunner, E.J. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Long-Term Changes in Aortic Stiffness: The Whitehall II Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2017, 6, e005974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, J.Y.; Grunseit, A.; Midthjell, K.; Holmen, J.; Holmen, T.L.; Bauman, A.E.; van der Ploeg, H.P. Cross-sectional associations of total sitting and leisure screen time with cardiometabolic risk in adults. J Sci Med Sport 2014, 17, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Wilkens, L.R.; Park, S.Y.; Goodman, M.T.; Monroe, K.R.; Kolonel, L.N. Association between various sedentary behaviours and all-cause, cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality: the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol 2013, 42, 1040–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wennman, H.; Vasankari, T.; Borodulin, K. Where to Sit? Type of Sitting Matters for the Framingham Cardiovascular Risk Score. AIMS Public Health 2016, 3, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, W.; Park, H.Y.; Lim, K.; Park, J. The role of habitual physical activity on arterial stiffness in elderly Individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Exerc Nutrition Biochem 2017, 21, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiva, A.M.; Martínez, M.A.; Cristi-Montero, C.; Salas, C.; Ramírez-Campillo, R.; Díaz Martínez, X.; Aguilar-Farías, N.; Celis-Morales, C. [Sedentary lifestyle is associated with metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors independent of physical activity]. Rev Med Chil 2017, 145, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Moon, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kong, M.H.; Oh, Y.H. Sedentary Lifestyle: Overview of Updated Evidence of Potential Health Risks. Korean J Fam Med 2020, 41, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tigbe, W.W.; Granat, M.H.; Sattar, N.; Lean, M.E.J. Time spent in sedentary posture is associated with waist circumference and cardiovascular risk. Int J Obes (Lond) 2017, 45, 689–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caparello, G.; Galluccio, A.; Giordano, C.; Lofaro, D.; Barone, I.; Morelli, C.; Sisci, D.; Catalano, S.; Andò, S.; Bonofiglio, D. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet pattern among university staff: a cross-sectional web-based epidemiological study in Southern Italy. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2020, 71, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Lista, J.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Garcia-Rios, A.; Perez-Caballero, A.I.; Perez-Jimenez, F.; Lopez-Miranda, J. Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Risk: Beyond Traditional Risk Factors. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2016, 56, 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granic, A.; Sayer, A.A.; Robinson, S.M. Dietary Patterns, Skeletal Muscle Health, and Sarcopenia in Older Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahni, S.; Mangano, K.M.; McLean, R.R.; Hannan, M.T.; Kiel, D.P. Dietary Approaches for Bone Health: Lessons from the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2015, 13, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Rey, J.; Roncero-Martín, R.; Rico-Martín, S.; Rey-Sánchez, P.; Pedrera-Zamorano, J.D.; Pedrera-Canal, M.; López-Espuela, F.; Lavado García, J.M. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Bone Mineral Density in Spanish Premenopausal Women. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovic, T.H.; Ali, S.R.; Ibrahim, N.; Jessop, Z.M.; Tarassoli, S.P.; Dobbs, T.D.; Holford, P.; Thornton, C.A.; Whitaker, I.S. Could Vitamins Help in the Fight Against COVID-19? Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daviglus, M.L.; Bell, C.C.; Berrettini, W.; Bowen, P.E.; Connolly, E.S., Jr.; Cox, N.J.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.M.; Granieri, E.C.; Hunt, G.; McGarry, K. , et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference statement: preventing alzheimer disease and cognitive decline. Ann Intern Med 2010, 153, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.L.; Piano, M.R.; Thur, L.A.; Peters, T.A.; da Silva, A.L.G.; Phillips, S.A. The effects of repeated binge drinking on arterial stiffness and urinary norepinephrine levels in young adults. J Hypertens 2020, 38, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Sanchez, J.; Garcia-Ortiz, L.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, E.; Maderuelo-Fernandez, J.A.; Tamayo-Morales, O.; Lugones-Sanchez, C.; Recio-Rodriguez, J.I.; Gomez-Marcos, M.A. The Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption With Vascular Structure and Arterial Stiffness in the Spanish Population: EVA Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2020, 44, 1816–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krittanawong, C.; Isath, A.; Rosenson, R.S.; Khawaja, M.; Wang, Z.; Fogg, S.E.; Virani, S.S.; Qi, L.; Cao, Y.; Long, M.T. , et al. Alcohol Consumption and Cardiovascular Health. Am J Med 2022, 135, 1213–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roerecke, M. Alcohol’s Impact on the Cardiovascular System. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claas, S.A.; Arnett, D.K. The Role of Healthy Lifestyle in the Primordial Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2016, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahad, O.; Schmitt, V.H.; Arnold, N.; Keller, K.; Prochaska, J.H.; Wild, P.S.; Schulz, A.; Lackner, K.J.; Pfeiffer, N.; Schmidtmann, I. , et al. Chronic cigarette smoking is associated with increased arterial stiffness in men and women: evidence from a large population-based cohort. Clin Res Cardiol 2023, 112, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münzel, T.; Hahad, O.; Kuntic, M.; Keaney, J.F.; Deanfield, J.E.; Daiber, A. Effects of tobacco cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and waterpipe smoking on endothelial function and clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 4057–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, A.E.; Howlett, S.E. Differences in Cardiovascular Aging in Men and Women. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018, 1065, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lifestyles | Global (501) | Men (249) | Women (252) | p value | |||

| Score the MD | 7.15 | ± 2.07 | 6.68 | ± 1.97 | 7.60 | ± 2.08 | <0.001 |

| Adherence to DM, n (%) | 214 | 42.7% | 89 | 35.7% | 125 | 49.6% | 0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption, (g/W) | 40.47 | ± 63.15 | 61.54 | ± 74.65 | 19.64 | ± 39.54 | <0.001 |

| Adequate alcohol consumption, n (%) | 251 | 50.1% | 94 | 37.8% | 157 | 62.3% | <0.001 |

| Years of smoking | 12.98 | ± 17.41 | 14.43 | ± 18.91 | 11.55 | ± 15.69 | 0.064 |

| Never smoked, n (%) | 367 | 73.3% | 183 | 73.5% | 184 | 73.0% | 0.920 |

| Total physical activity, (h/W) | 27.09 | ± 9.52 | 26.01 | ± 9.51 | 28.17 | ± 9.43 | 0.011 |

| More than 26 h/W, n (%) | 246 | 49.7% | 107 | 43.1% | 139 | 56.3% | 0.004 |

| Sitting Time, (h/W) | 140.75 | ± 9.56 | 141.78 | ± 9.57 | 139.72 | ± 9.45 | 0.017 |

| Less than 142 h/W, n (%) | 253 | 51.1% | 113 | 45.6% | 140 | 56.7% | 0.015 |

| Number of healthy lifestyles | 2.66 | ± 1.29 | 2.35 | ± 1.24 | 2.96 | ± 1.28 | <0.001 |

| More than 2 healthy lifestyles, n (%) | 253 | 50.5% | 102 | 41.0% | 151 | 59.9% | <0.001 |

| Conventional risk factors | |||||||

| Age (years) | 55.90 | ± 14.24 | 55.95 | ± 14.31 | 55.85 | ± 14.19 | 0.935 |

| Systolic blood pressure, (mmHg) | 120.69 | ± 23.13 | 126.47 | ± 19.52 | 114.99 | ± 24.96 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, (mmHg) | 75.53 | ± 10.10 | 77.40 | ± 9.38 | 73.67 | ± 10.46 | <0.001 |

| Mean arterial pressure, (mmHg) | 90.58 | ± 12.61 | 93.76 | ± 11.13 | 87.44 | ± 13.21 | <0.001 |

| Pulse pressure, (mmHg) | 45.17 | ± 19.81 | 49.06 | ± 16.68 | 41.31 | ± 21.83 | <0.001 |

| Hypertensive, n (%) | 147 | 29.3% | 82 | 32.9% | 65 | 25.8% | 0.095 |

| Antihypertensive, n (%) | 96 | 19.2% | 50 | 20.1% | 46 | 18.3% | 0.650 |

| Total-Cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 194.76 | ± 32.49 | 192.61 | ± 32.26 | 196.88 | ± 32.65 | 0.142 |

| LDL-Cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 115.51 | ± 29.37 | 117.43 | ± 30.12 | 113.61 | ± 28.54 | 0.148 |

| HDL-Cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 58.75 | ± 16.16 | 53.19 | ± 14.12 | 64.22 | ± 16.20 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, (mg/dl) | 103.06 | ± 53.20 | 112.28 | ± 54.40 | 93.95 | ± 50.46 | <0.001 |

| Atherogenic index | 3.53 | ± 1.07 | 3.84 | ± 1.12 | 3.24 | ± 0.93 | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemic | 191 | 38.1% | 95 | ± 38.2% | 96 | 38.1% | 98.9% |

| Lipid-lowering, n (%) | 102 | 20.4% | 49 | 19.7% | 53 | 21.0% | 0.740 |

| Plasma glucose, (mg/dl) | 88.21 | ± 17.37 | 90.14 | ± 18.71 | 86.30 | ± 15.73 | 0.013 |

| HbA1c, (%) | 5.49 | ± 0.56 | 5.54 | ± 0.63 | 5.44 | ± 0.47 | 0.043 |

| Diabetes mellitus tipe 2, n (%) | 38 | 7.6% | 26 | 10.4% | 12 | 4.8% | 0.018 |

| Hypoglycemic, n (%) | 35 | 7.0% | 23 | 9.2% | 12 | 4.8% | 0.055 |

| Body mass index, (kg/m2) | 26.52 | ± 4.23 | 26.90 | ± 3.54 | 26.14 | ± 4.79 | 0.044 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 93.33 | ± 12.01 | 98.76 | ± 9.65 | 87.93 | ± 11.70 | <0.001 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 94 | 18.8% | 42 | 16.9% | 52 | 20.6% | 0.304 |

| Abdominal obesity, n (%) | 193 | 38.6% | 78 | 31.3% | 115 | 45.8% | 0.001 |

| Structure. vascular function and aging | |||||||

| Intima Media Thickness. (mm) | 0.682 | ± 0.109 | 0.699 | ± 0.116 | 0.665 | ± 0.100 | 0.001 |

| cfPWV, (m/sec) | 6.53 | ± 2.03 | 6.86 | ± 2.20 | 6.21 | ± 1.79 | <0.001 |

| Vascular Aging Index | 61.23 | ± 12.86 | 63.47 | ± 13.75 | 59.04 | ± 11.54 | <0.001 |

| Lifestyles | HVA (94, 18.9%) | Non HVA (407, 81.1%) | p | ||

| Score the DM | 6.91 | ±2.20 | 7.20 | ±2.05 | 0.226 |

| Adherence to DM, n (%) | 33 | 35.1% | 180 | 44.6% | 0.106 |

| Alcohol consumption, (g/W) | 34.89 | ±57.99 | 41.94 | ±64.46 | 0.331 |

| Adequate alcohol consumption, n (%) | 47 | 50.0% | 202 | 50.0% | 1.000 |

| Years of smoking | 12.45 | ±15.41 | 12.90 | ±17.70 | 0.820 |

| Never smoked, n (%) | 65 | 69.1% | 299 | 67.0% | 0.037 |

| Total physical activity, (h/W) | 29.19 | ±9.79 | 26.58 | ±9.41 | 0.017 |

| More than 26 h/W, n (%) | 56 | 60.2% | 188 | 47.1% | 0.028 |

| Sitting Time, (h/W) | 138.57 | ±9.81 | 141.28 | ±9.44 | 0.014 |

| Less than 142 h/W, n (%) | 57 | 61.3% | 194 | 48.6% | 0.029 |

| Number of healthy lifestyles | 2.74 | ±1.20 | 2.63 | ±1.32 | 0.444 |

| More than 2 healthy lifestyles, n (%) | 57 | 60.6% | 195 | 48.3% | 0.039 |

| Conventional risk factors | |||||

| Age (years) | 52.64 | ±13.29 | 56.66 | ±14.34 | 0.010 |

| Systolic blood pressure, (mmHg) | 109.59 | ±12.61 | 123.32 | ±24.28 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, (mmHg) | 71.10 | ±8.28 | 76.56 | ±10.24 | <0.001 |

| Mean arterial pressure, (mmHg) | 83.93 | ±9.00 | 92.14 | ±12.87 | <0.001 |

| Pulse pressure, (mmHg) | 38.48 | ±8.90 | 46.76 | 21.30 | <0.001 |

| Hypertensive, n (%) | 0 | 0.0% | 147 | 36.4% | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive, n (%) | 0 | 0.0% | 96 | 19.3% | <0.001 |

| Total-Cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 193.27 | ±32.39 | 194.95 | ±32.50 | 0.651 |

| LDL-Cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 113.42 | ±28.02 | 115.87 | ±29.72 | 0.469 |

| HDL-Cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 62.42 | ±18.00 | 57.85 | ±15.62 | 0.014 |

| Triglycerides, (mg/dl) | 83.33 | ±32.99 | 107.66 | ±55.97 | <0.001 |

| Atherogenic index | 3.32 | ±1.09 | 3.59 | ±1.06 | 0.027 |

| Dyslipidemic | 29 | 30.9% | 160 | 39.6% | 0.126 |

| Lipid-lowering, n (%) | 13 | 13.8% | 88 | 21.8% | 0.086 |

| Plasma glucose, (mg/dl) | 83.41 | ±10.27 | 89.41 | ±18.49 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c, (%) | 5.30 | ±0.29 | 5.53 | ±0.59 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus tipo 2, n (%) | 0 | 0.0% | 38 | 9.4% | 0.002 |

| Hypoglycemic, n (%) | 0 | 0.0% | 35 | 7.0% | 0.003 |

| Body mass index, (kg/m2) | 24.43 | ±3.26 | 27.00 | ±4.29 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 88.48 | ±9.41 | 94.45 | ±12.28 | <0.001 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 6 | 6.4% | 88 | 21.8% | 0.001 |

| Abdominal obesidad, n (%) | 21 | 22.3% | 171 | 42.4% | <0.001 |

| Structure. vascular function and aging | |||||

| Intima Media Thickness. (mm) | 0.62 | ±0.08 | 0.70 | ±0.11 | <0.001 |

| cfPWV, (m/sec) | 4.83 | ±0.75 | 6.93 | ±2.02 | <0.001 |

| Vascular Aging Index | 50.51 | ±5.67 | 63.74 | ±12.78 | <0.001 |

| VAI | Global (501) | Men (249) | Women (251) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Score the MD | -0.102* | -0.082* | 0.058 |

| Alcohol consumption,g/W | 0.228** | 0.221** | -0.040 |

| Year smoking | 0.092* | 0.105 | 0.010 |

| Total physical activity, (h/W) | -0.158* | -0.120 | -0.161* |

| Sitting Time, (h/W) | 0.165** | 0.135* | -0.162* |

| Number of healthy lifestyles | -0.199** | -0.197** | -0.063 |

| VAI | β | (IC | 95%) | p |

| Global | ||||

| Score the DM | -0.056 | -0.418 | to 0.307 | 0.763 |

| Alcohol consumption,g/W | 0.020 | 0.008 | to 0.032 | 0.001 |

| Year smoking | 0.028 | -0.013 | to 0.069 | 0.185 |

| Total physical activity, (h/W) | -0.102 | -0.176 | to -0.028 | 0.007 |

| Sitting Time, (h/W) | 0.109 | 0.036 | to 0.183 | 0.004 |

| Number of healthy lifestyles | -0.640 | -1.195 | to -0.086 | 0.024 |

| Men | ||||

| Score the MD | -0.044 | -0.598 | to 0.509 | 0.875 |

| Alcohol consumption,g/W | 0.020 | 0.005 | to 0.034 | 0.008 |

| Year smoking | 0.045 | -0.014 | to 0.103 | 0.133 |

| Total physical activity, (h/W) | -0.096 | -0.203 | to 0.011 | 0.080 |

| Sitting Time, (h/W) | 0.108 | 0.001 | to 0.214 | 0.048 |

| Number of healthy lifestyles | -1.054 | -1.741 | to -0.367 | 0.003 |

| Women | ||||

| Score the MD | -0.010 | -0.459 | to 0.439 | 0.965 |

| Alcohol consumption,g/W | -0.005 | -0.027 | to 0.018 | 0.690 |

| Year smoking | -0.023 | -0.080 | to 0.033 | 0.416 |

| Total physical activity, (h/W) | -0.099 | -0.195 | to -0.002 | 0.044 |

| Sitting Time, (h/W) | 0.099 | 0.195 | to 0.003 | 0.043 |

| Number of healthy lifestyles | -0.256 | -0.820 | to 0.309 | 0.373 |

| VAI | OR | (IC | 95%) | p |

| Global | ||||

| MD adhesion | 0.571 | 0.333 | to 0.981 | 0.042 |

| AA consumption | 0.993 | 0.606 | to 1.627 | 0.977 |

| Smoker | 0.648 | 0.375 | to 1.119 | 0.119 |

| PAT > 26 h/W | 1.735 | 1.048 | to 2.871 | 0.032 |

| ST - 142 h/W | 1.696 | 1.025 | to 2.805 | 0.040 |

| > 2 HL | 1.877 | 1.123 | to 3.136 | 0.016 |

| Men | ||||

| MD adhesion | 0.413 | 0.170 | to 1.004 | 0.051 |

| AA consumption | 0.852 | 0.425 | to 1.708 | 0.653 |

| Smoker | 0.382 | 0.162 | to 0.902 | 0.028 |

| PAT > 26 h/W | 1.825 | 0.878 | to 3.793 | 0.107 |

| ST - 142 h/W | 1.738 | 0.838 | to 3.604 | 0.136 |

| > 2 HL | 1.998 | 0.956 | to 4.175 | 0.066 |

| Women | ||||

| MD adhesion | 0.766 | 0.377 | to 1.558 | 0.462 |

| AA consumption | 0.968 | 0.465 | to 2.014 | 0.931 |

| Smoker | 0.812 | 0.381 | to 1.731 | 0.589 |

| PAT > 26 h/W | 1.668 | 0.817 | to 3.404 | 0.160 |

| ST - 142 h/W | 1.655 | 0.810 | to 3.379 | 0.167 |

| > 2 HL | 1.769 | 0.848 | to 3.692 | 0.128 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).