1. Introduction

Ethnographic and historical museums play a crucial role in representing the past, while contemporary museums are concerned with the concepts of modern or modernism and do not offer elements of the past to the public. Preserving and documenting a way of life that is disappearing or has vanished is always a challenging task for any museum. Each museum is defined by its collection. Ethnographic and historical museums preserve traditional, tangible and intangible heritage, and their mission is to collect works of art created under different social, cultural, religious and political conditions. Furthermore, there are variations in urban and rural lifestyles and how these are interpreted and presented to the public. Therefore, ethnographic museums need to devise viable and feasible concepts or methods for displaying the ethnographic view of the rustic environment and everyday realities of rural life that are compatible with the museum’s available space and budget.

The modern ethnographic museum is required to engage with a broader audience and assume new responsibilities. It is encouraged to be creative and make efforts to respond to local needs and accommodate requests from local and international visitors. They must become true keepers of heritage, taking care of the preservation of a rapidly disappearing material culture and the human knowledge and skills that created it.

Visiting a museum can be a unique experience, yet visitors may take the intensive labour, knowledge and enthusiasm invested in the design and layout of the museum’s exhibition for granted. Depending on the type of museum objects, there are various requirements and challenges when displaying three–dimensional textile objects subject to strict professional rules. For instance, the objects which are stored flat must be exhibited in a three–dimensional form. Furthermore, as clothing is designed to fit a human body, there is great importance placed on choosing adequate ways to display three–dimensional textile objects to create a uniform yet distinctive appearance across the collection and the selection of suitable mannequins, shaping them to fit a particular garment, and positioning them to create an ambience that conveys the intended story and meaning of an exhibition is a challenging task.

Mannequins and torsos come in many shapes, styles, sizes, finishes, materials and prices, and the choice of mannequin and the best display techniques will depend on whether exhibiting art, history, fashion, anthropology or ethnicity [

1,

2]. The mannequins acquired for exhibiting museum objects may often not comply with the shape and proportions of the garment to be exhibited on it, and, therefore, they need to be adapted to its specific cut, dimensions and shape [

3]. Additionally, the materials used for display must be museum quality and sustainable.

An example highlighting the challenges of exhibiting ethnographic costumes is the interinstitutional project of replacing display mannequins in the Ethnographic Museum of Dubrovnik. Four individual specialised museums constitute the Dubrovnik Museums and the museums are housed in significant heritage buildings: the Cultural History Museum in the Rector’s Palace, the Maritime Museum in Fort St John and the Ethnographic Museum in the old civic granary [

4]. The Archaeological Museum lacks space to display a permanent exhibition. Each museum has rich holdings that tell the stories of the cultural, historical, traditional, material and intangible heritage of the city of Dubrovnik and the area of the former Dubrovnik Republic.

The existing mannequins in the Ethnographic Museum in Dubrovnik were not entirely acceptable for display, therefore, it was decided to gradually replace them with more appropriate ones while respecting the strict code of ethics, professional standards and competencies of the conservation–restoration profession. The project “Modifying of Display Mannequins for Ethnographic Costumes” took place over two successive years (2018–2019) with an objective to replace the existing mannequins, raise awareness of the importance of cultural heritage and educate students, colleagues and the general public on how to display ethnographic clothing, which can be a demanding undertaking. The focus was on effective collaboration between institutions as an example of good practice and heritage care. Of a total of 17 display mannequins from the museum’s permanent exhibition needing to be replaced, to date, six have been adapted in these workshops.

2. The Use of Mannequins: The Past and the Present

The selection of an adequate mannequin system support raises questions about the advantages and disadvantages of the older style straight and rigid mannequin versus the newer style flexible mannequin that helps to create a more natural and desirable posture. The former type of mannequin is typically made of materials harmful to the museum objects exhibited and may come with an iron pole that runs straight through the body. The function of an iron rod is to support the mannequin, and it can be used with both straight and flexible mannequins. Some museums paint the lower exposed part of the iron rod using the same colour as the exhibition floor to make it discreet or hide it from public view [

5].

There is a difference between displaying folk dress and fashion. While ethnographic costumes may share some characteristics with fashionable clothing, their primary purpose is to reveal the way of life and customs of a region or country. Folk dress is considered as belonging to the field of ethnology and ethnography, while fashionable dress is considered an expression of art history. As a result, ethnographic costume as an expression of geographic locations and social structures is placed outside the fashion discipline [

5]. Traditional clothing follows certain conventions to express the sensorial, emotional, social, anthropological and phenomenological aspects of wearing these clothes; rules that should be respected when exhibiting them within a museum display.

The appropriate display of historical and ethnographical textiles contributes to better and longer preservation of these sensitive objects of cultural heritage, and highlights the visual impression and artistic experience of the object. For example, in tailoring, a garment is made according to the structure and proportions of the human body for whom it is sewn. Conversely, in the museum, there is a requirement to shape the mannequin to correspond to the garment’s shape. The shape and dimensions of a mannequin affect the quality of the presentation of a three–dimensional garment, and to preserve the intrinsic shape of a garment, it must not be mounted too tightly or loosely on a mannequin [

3].

3. The Ethnographic Museum in Dubrovnik and the Mannequins of the Sculptor Zvonimir Lončarić (“Riba”)

The granary building, which houses the Ethnographic Museum, was constructed in 1590. A four–story building, it contained fifteen storage pits on the ground floor and spaces for drying the grain on the upper floors. It remained the state granary until the fall of the Republic in 1808. The colloquial name Rupe (The Holes) derives from the vernacular term for underground wheat silos carved out of the bedrock or tufa [

6]. The Granary entered the twentieth century as a damaged structure requiring reconstruction. Thanks to the advocacy of individuals and the Dubrovnik Society for the Development of Dubrovnik and Surroundings (DUB), the building was, from 1940, used as a museum space for the intangible and tangible heritage display (for part of the exhibition of Dubrovnik seafaring in the Middle Ages) and later was used as the lapidarium of the Archaeological Museum [

4,

7].

The Ethnographic Museum was established in the early twentieth century and started with a collection of objects of traditional culture. Later, a schoolteacher, Jelka Miš (1875–1956), considerably augmented the collection by donating traditional folk attire and needlework [

8]. The first permanent ethnographic display in Fort St John opened in the mid–twentieth century. Since then, a textile preparator’s workshop has also been in operation. In 1953, the Commission for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia donated 805 items (textiles and handicrafts) to the Dubrovnik Museum for the new permanent exhibition of the Ethnographic Department. In 1954, the ethnologist Antun Kalameta staged an exhibition entitled Folk Arts of Yugoslavia [

9]. This exhibition was open to the public until the renovation of the building after an earthquake in 1979 [

4]. The National Art of Yugoslavia consisted of 1400 exhibits from various areas and techniques of folk art. In the period 1949–1952, the exhibition visited several European cities: London, Edinburgh, The Hague, Amsterdam, Zürich, Oslo, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Brussels, Paris and Geneva. [

10].

A significant part of the holdings of the Ethnographic Museum consists of textile materials arranged in ten collections comprising the traditional attire of the Dubrovnik area, Croatia and neighbouring states. The concept and design of the museum’s permanent collection dates from 1991 and was partially based on a synopsis of the collection made by the ethnologist Dr Katica Benc Bošković in 1985 [

11]. The ground floor of the museum presents the storage of grain in situ. Displayed on the first floor is traditional economic activities alongside traditional rural architecture and house interiors from the environs of Dubrovnik. On the second floor are examples of clothing and ornaments worn for ceremonial occasions from micro–locations in the Dubrovnik region. Unique specimens of textile handicrafts from the second half of the nineteenth century are particularly valuable. The housing and presentation of textiles in a historical building present some problems because of the oscillations of humidity and temperature [

12].

The museum equipment and the mannequins used to display the clothing reflect the guidelines for the presentation of material established by the museum in the 1980s. Mannequins created by the academy–trained sculptor and printmaker Zvonimir Lončarić, nicknamed “Riba”, were chosen for the permanent display of the Ethnographic Museum in 1991 (

Figure 1).

Lončarić’s museum mannequins enabled a complete depiction of the traditional manner of dressing. They had moveable limbs, and it was possible to display authentically the lower parts of the attire (trousers, socks, toe warmers, gaiters, shoes and sandals). The greatest value of the mannequins is inherent in the artist’s design of the heads and faces, on which the headpieces, essential components of the traditional manner of dress, could be displayed. Since the mannequins are composed of various organic and inorganic materials (for example, terracotta for the hands and heads, acrylic resin for the torso, and wood and metal parts for the limbs and joints), mechanical damage would inevitably arise, requiring urgent preventive protection of the textiles as well as long–term solutions for the presentation of the traditional manner of dressing [

13,

14].

The faces of the mannequins are sculpted in terracotta based on the facial features of the people from local rural regions. For this reason, the museum considered them as protected artworks in the permanent exhibition. However, the mannequins had a harmful effect on the textiles displayed. In 2018, after recommendations from conservator–restorers about the best manner of exhibiting the restored textiles, the removal of the museum mannequins made by sculptor Lončarić began. On account of the artist’s interpretation and shaping of faces and heads, they will be kept as a testimony to the artist, the time they were produced and how the material was presented and valorised as cultural property.

4. The Interinstitutional Project of Replacing Display Mannequins

With the implementation of preventive conservation measures on the textiles in 2009, changes were observed in the textiles in direct contact with the original mannequins. As mentioned previously, they were made using various organic and inorganic materials, and direct exposure to these harmful materials intensified the rate of degradability. Additionally, the textiles in direct contact with the mannequin torsos adhered to the acrylic paint coating them. To mitigate the harmful effects, conservation measures were carried out, such as removing certain parts of the mannequin (the metal, wooden and ceramic parts of the limbs) and protecting the torso with cotton undershirts and acid–free tissue paper. Since then, a more intensive collaboration has started with the University of Dubrovnik, the Department of Art and Restoration, the Croatian Restoration Institute and textile departments in Zagreb and Ludbreg. These institutions urged the replacement of those old, inadequate mannequins. In 2018, after completing a series of conservation projects within the collection, it was decided to gradually replace the existing mounts (six showcases and 17 mannequins total) with new museum–quality mannequins.

It took many years to find solutions relating to how valuable three–dimensional textile objects could be exhibited while satisfying a number of requirements, such as the museum experience and the curatorial story presented to the public, all in accordance with the conservation and restoration guidelines. The project, “Modifying of Display Mannequins for Ethnographic Costumes”, developed a solution meeting a predefined set of criteria and goals to better represent and protect cultural heritage. The project was organised by the textile workshop of the art restoration department at the University of Dubrovnik, in cooperation with the Croatian Conservation Institute and Ethnographic Museum of Dubrovnik Museums. Two project–based learning workshops were held in the textile conservation and restoration workshop space at the University of Dubrovnik.

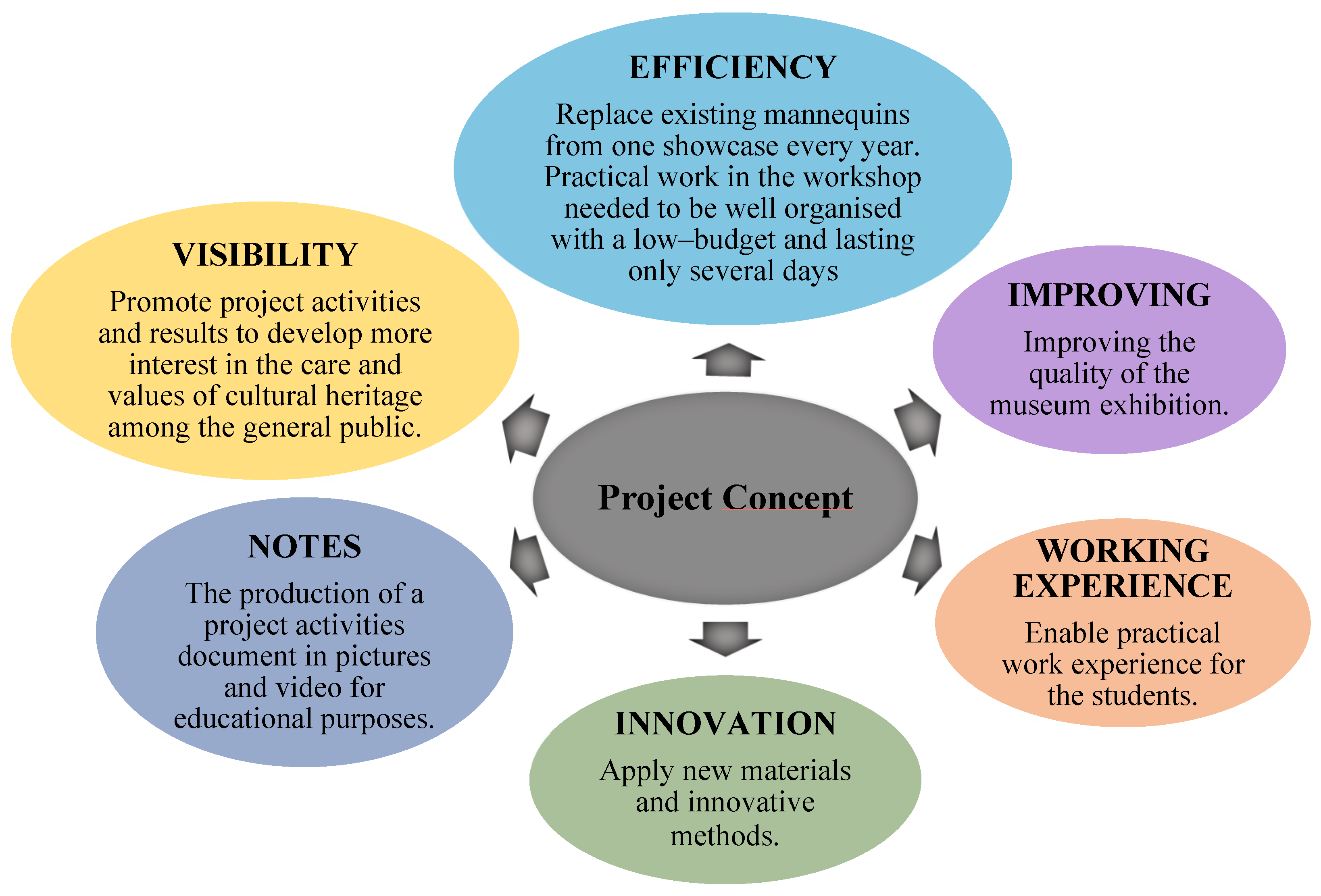

Figure 2.

The project’s principal goals.

Figure 2.

The project’s principal goals.

In order to exhibit hats, hair accessories and shoes, it was important that replacement mannequins have arms, legs and a head. The Ethnographic Museum purchased

Polystar soft and flexible mannequins as they met these requirements (

Figure 3, “Ideen & Technik”,

https://www.polyform.de). A further advantage of the Polystar mannequins is the detachable hands system allowing for easier manipulation of the garments during trials and final mounting [

15]. Each mannequin was modified and shaped according to the specific form of the ethnographic costume to be displayed. To shape the mannequin’s body, it is necessary to dress the mannequin with the costume multiple times. To preserve the original, a replica of a specific garment can be made [

3,

15]. In some cases, this action is unnecessary when the costume being mounted is in good condition.

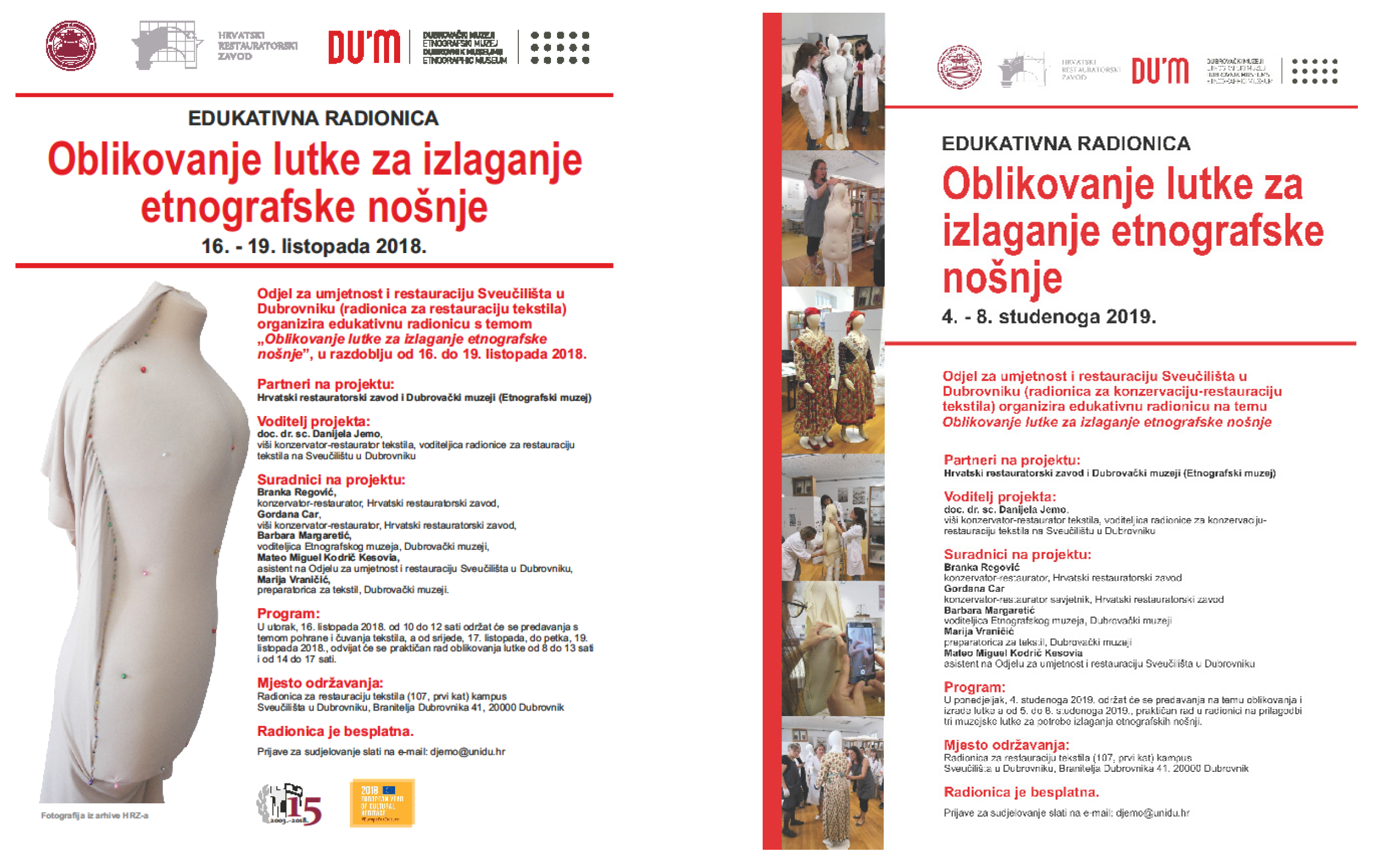

4.1. Project Stages

A distinct set of activities characterised each project stage. During Stage One (16 October–19 October 2018), three female mannequins were modified for three ethnographic costumes, and in Stage Two (4 November–8 November 2019), two female and one male mannequin were modified for three ethnographic costumes (

Figure 3). Each workshop started with educational lectures from an interinstitutional team of textile conservators about making mannequins accompanied with examples and was followed by practical work in the workshop.

4.1.1. Stage 1: Modifying Three Female Mannequins for Three Ethnographic Costumes

The first workshop “Modifying of Display Mannequins for Ethnographic Costumes” occurred during the European Year of Cultural Heritage, between 16 October–19 October 2018 (

Figure 4). Delivered on the first day were a series of lectures. The lectures began with the history of the Ethnographic Museum in Dubrovnik and present–day insights into the museum’s exhibitions and experiences. This was followed by topics dealing with professional guidelines and problems related to displaying three–dimensional textiles and the application of different materials for creating and shaping mannequins which were complemented with case examples. During the first stage of the project, a workshop was held to modify three specialised display mannequins to exhibit three distinct ethnographic women’s ceremonial costumes from Župa, Rijeka Dubrovačka and the Dubrovnik Littoral. These valuable and unique ethnographic garments are characterised by a baroque cut that appeared in traditional costumes at the end of the nineteenth century.

4.1.2. Stage 2: Modifying Two Female and One Male Mannequin for Three Ethnographic Costumes

Stage two took place between 4–8 November 2019 (

Figure 3). While during the first workshop, only female mannequins were modified, in this workshop, the emphasis was on the male–type mannequin. Female mannequins wearing long dresses can be easily fixed to a stand with a metal holder, and the pole hidden from view, but the male version, which wears wide pants stopping just below the knees, requires a different approach. The construction involved a method that allows the display mannequin to hang from an external support situated behind the mannequin and hidden between the different layers of the costume. The balance and stability of the mannequin and all additional materials therefore needed special attention [

16]. For this occasion, to secure them properly and avoid damaging the objects, Ivan Mladošić, a stone restorer at the Dubrovnik Museums, made custom metal supports for female and male display mannequins. The traditional women’s costumes selected for this stage of the project did not include headscarves as they posed a unique challenge to designing and making special wigs that faithfully represent the art of traditional hairstyles and wedding headdresses [

17].

Accompanying lectures, held at the University of Dubrovnik, covered a range of topics concerning effective methods for preparing ethnographic costumes for display, mounting costumes for display, various support systems and the care and display of museum exhibitions. Practical work also took place in the textile conservation and restoration workshop at the University of Dubrovnik. An exhibition of posters covering the workshop’s topics ran concurrently on the university’s campus.

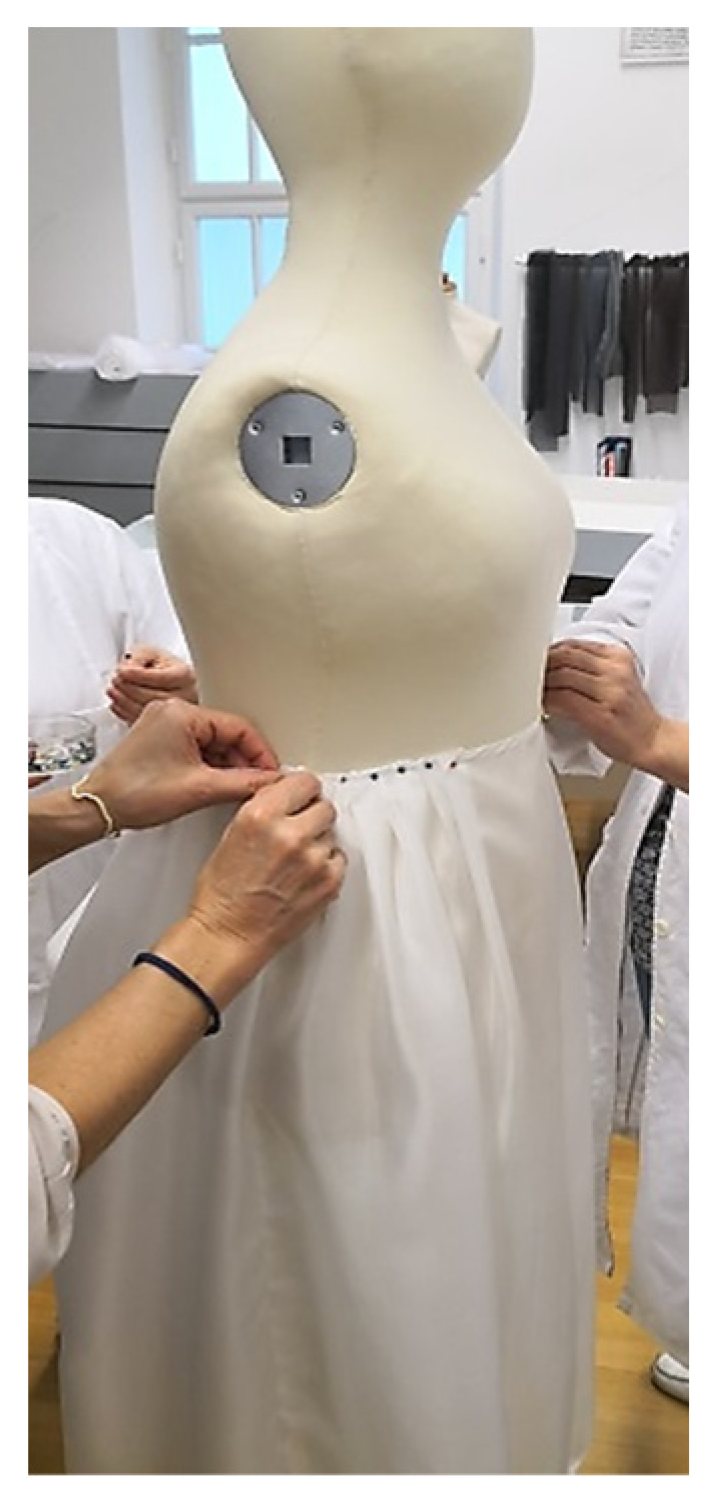

4.2. Practical Work: Modifying of Display Mannequins for Ethnographic Costumes

A tailored garment is cut and shaped in relation to the body of the person for whom it is sewn. For the display of museum objects, the existing mannequin needs to be modified to match the size and shape of the specific clothing item that it will display. Modifying a display mannequin for exhibiting three–dimensional objects requires specialist knowledge, skills and competencies, and this project offered its participants the opportunity to develop these criteria.

The specialised Polystar mannequins purchased by the Dubrovnik Museums were modified to exhibit different ethnographic costumes from the collection of the Ethnographic Museum.

To shape the mannequin’s body with polyester wadding, it is necessary to dress the mannequin with the costume multiple times. After observing the costume on the mannequin, new layers of polyester wadding are strategically added to match the garment’s shape and size (

Figure 5). Building up the torso by applying layers of wadding until it is exactly the right shape and size to fit the garment is very challenging task. It is best to apply padding to the front and back of the torso, rather than the sides. After the first fitting, the padding was stitched directly to the soft mannequin body using a large, curved needle. Applied layers of polyester wadding followed the shape and size of the garment. The mannequin’s face and hands were also shaped in proportion to the size of the torso, and to enable them to wear specific decorations on the head and carry an apple in their hands (

Figure 10).

After the second fitting and any final alterations or additions to the padding, the mannequins were covered with stretch fabric (

Figure 5). The prewashed fabric was cut into two pieces, one to cover the front and the other to cover the back side of the torso, neck and head. Covering the entire torso with stretch fabric requires considerable skill and knowledge concerning the manipulation of the fabric to ensure a perfect fit. The fabric was then pinned to the mannequin with the wrong side facing out. In this way, the hem of the fabric ends up hidden once turned inside out. The position of the pins was marked, and the positioning lines of the fabrics were additionally marked with tailor’s chalk, which assisted as a guide during the sewing process. The front and back pieces were also marked and then stitched together using an overlock stitch. The new cover was placed over the mannequin, and the bottom edge was finished with a hand stitch.

Figure 6.

Covering the mannequin with stretch fabric (left) and sewing the cover (right).

Figure 6.

Covering the mannequin with stretch fabric (left) and sewing the cover (right).

When displaying ethnographic costumes, several challenges emerged beyond shaping the mannequin’s body such as:

Making a silk petticoat to hold the silhouette of an ethnographic costume (

Figure 7). A skirt in the collection required a petticoat, and the workshop participants learned how to sew one suitable for the skirt. To add volume to the skirt, they had to determine the correct amount of material to use in the petticoat, and how to shape and sew the pleats. It was a valuable task for the participants to learn.

Making a custom metal support for the male mannequin (

Figure 8). As the male costume includes trousers and shoes, finding the most suitable solution to fix the mannequin to the stand was necessary. The metal support was made from one straight rod, on whose end is vertically attached a “C” shape rod that encircles the mannequin’s waist. The challenge lay in how to secure the metal rod to a male mannequin wearing pants and at what height and shape. The rod around the mannequin’s waist was concealed in the various layers of the costume without compromising the aesthetics or damaging the textile. As it is not ideal for metal to be in contact with textiles, the rod was covered with protective material.

Creating hair and styling it into shapes encapsulating traditional hairstyles suitable for exhibiting hats and hair accessories. (

Figure 9). The participants were not familiar with the methods or materials for making a wig. For this purpose, a crafting technique was invented that involved knotting and knitting wool threads in different shades of brown to achieve hairstyles that reflected those of the period.

Shaping arms and legs. All ethnographic costumes have the appropriate shoes, and some female mannequins have decorative props to hold in their hands (

Figure 10). For an authentic display of ethnographic costumes, all mannequins’ body parts had to be shaped correctly. Padding the mannequin’s arms and legs in proportion to the torso was a challenging task. To achieve the desired shape and size, layers of wadding were wrapped around the fingers and legs. As there are limits to the extent that costumes can be manipulated, the detachable and flexible arms of the Polystar mannequins proved to be useful for the fitting and shaping process.

4.3. The Project’s Educational Value

An important contribution of the educational workshops is their promotion of the value of textile heritage and the importance of safe and effective costume mounting for long–term heritage preservation. It was a rare educational and training opportunity for students and colleagues from other institutions, and they could practice the methods of costume mounting and develop innovative solutions to display textile objects. In addition to conservation and restoration students, experts from other institutions, such as the Linđo Folklore Ensemble from Dubrovnik, the Ethnographic Museum of Zagreb and the Varaždin City Museum participated in the workshops. All the participants from the University of Dubrovnik received certificates of participation. The project created interest among the general public and the media, with local and national television stations, newspapers and local and institutional websites publishing stories on the project.

5. Conclusions

This case study highlighted the challenges of exhibiting diverse ethnographic costumes by discussing past presentation methods and how new solutions have been implemented conforming to the modern conservation–restoration profession. The mannequins initially used in the Ethnographic Museum were created by the artist Zvonimir Lončarić (“Riba”). These mannequins had accentuated body parts, for example, the hips, shoulders, legs and arms, and expressed the artist’s poetic nature, however, they were not practical for displaying ethnographic costumes. Therefore, with the project “Modifying of Display Mannequins for Ethnographic Costumes”, the gradual process of replacing the mannequins commenced. It was a demanding and challenging task, particularly the aspects of producing a customised metal support for the male mannequin and making the hair for hairstyles to exhibit head accessories. Ten mannequins created by Zvonimir Lončarić can still be seen in the permanent exhibition, 6 have been replaced by the workshops. Preventive conservation measures were carried out on the existing mannequins: the hands, which were made of ceramic and metal elements, were removed and the torso and legs were covered with high–quality conservation materials and insulated.

The educational workshops significantly contributed to promoting the value of textile heritage and the importance of contemporary, safe and effective costume mounting as a long–term heritage preservation. It was an exceptional education and training opportunity for the students and colleagues from other institutions to practice the methods of costume mounting and develop new solutions to display unique textile objects. Furthermore, the project contributed to advancing interinstitutional collaboration between cultural heritage institutions such as Dubrovnik Museums, the Art and Restoration Department of the University of Dubrovnik, and the Croatian Restoration Institute. Due to the COVID–19 pandemic, this project was suspended, however, the project partners wish to continue the collaboration and address further issues related to the permanent museum exhibition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.J, B.M. and M.M.K.K.; methodology, D.J.; validation, D.J, B.M. and M.M.K.K.; formal analysis, D.J, B.M. and M.M.K.K.; investigation, D.J, B.M. and M.M.K.K.; resources, D.J, B.M. and M.M.K.K.; data curation, D.J, B.M. and M.M.K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.J.; writing—review and editing, D.J, B.M. and M.M.K.K.; visualization, D.J, B.M. and M.M.K.K.; supervision, D.J.; project administration, D.J, B.M. and M.M.K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our special gratitude to our colleagues Gordana Car and Branka Regović from the Croatian Conservation Institute for their valuable guidance throughout the practical work and for sharing their longstanding experience and knowledge. We deeply appreciate their permanent support, work ethic and constant optimism.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fajardo, S.; Flecker, L.; Gatley, S.; Miller, K. Mounting Historic Dress for Display, Dress and Textile Specialists, London, England, 2015; pp. 14, Available online: https://www.dressandtextilespecialists.org.uk/dats-toolkits/ (accessed 30 August 2021.).

- Cooks, R. B.; Wagelie, J. J. Mannequins in Museums: Power and Resistance on Display, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, Abingdon, England, 2021, pp. 1–11.

- Flecker, L. A Practical Guide to Costume Mounting, Butterworth–Heinemann, Oxford, England, 2007, pp. xiii, 17, 45-48, 79.

- Dabelić, I. The Developmental Path of Dubrovnik Museums from 1872 to 2002, Dubrovnik Museums Miscellany 2004, Number 1, Dubrovnik, Croatia, pp. 7–30.

- Riegels Melchior, M.; Svensson, B. Fashion and Museums: Theory and Practice, Bloomsbury, London, England, 2014, p. 117.,119.

- Kipre, I. Rupe Granary: Granaries and the Storage of Grain in Dubrovnik, Dubrovnik Museums, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2014, p. 37.

- Menalo, R. Historical Development of the Archaeological Museum, Dubrovnik Museums Miscellany I 2004, Dubrovnik, Croatia, pp. 239–251.

- Benc–Bošković, K. The Teacher Jelka Miš in Ethnological and Museum Work, Ethnographic Museum Documentation, 1996, Volume 2, pp. 117–136.

- Marunčić, T. They Created Dubrovnik museums, Dubrovnik Museums Miscellany 2022, Number V., Dubrovnik, Croatia, p. 236.

- Šepić, D. Izložba narodne umjetnosti Jugoslavije/Exhibition of national art of Yugoslavia, Slovenski etnograf, 1953/1954, Issue 6/7, pp. 273–285.

- Dunatov, Lj. The permanent exhibitions of the Dubrovnik museums, Dubrovnik Museums Miscellany 2022, Number V., Dubrovnik, Croatia, pp. 233-242.

- Foekje, B. Unravelling Textiles: A Handbook for the Preservation of Textile Collections, Archetype Publications Ltd, London, 2007, pp. 38.

- Vraničić, M. Preventive Protection of Textile Material on Exhibition Manikins in the Permanent Display of the Ethnographic Museum in Dubrovnik, Dubrovnik Museums Miscellany 2015, Number III, Dubrovnik, Croatia, p. 327–334.

- Regović, B. Report on Conservation and Restoration Works Carried Out on Parts of Female Traditional Attire from Župa Dubrovačka, Skirt–Shirt, Inv. No. 1079D and Shirt Inv. No. 1079C from the Ethnographic Museum in Dubrovnik, In Croatian Conservation Institute Documentation, Zagreb, Croatia, 2010, p. 29.

- Pietsch, J.; Stolleis, K. Kölner Patrizier–und Bürgerkleidung des 17. Jahrhunderts: Die Kostümsammlung Hüpsch im Hessischen Landesmuseum Darmstadt, Abegg–Stiftung, Riggisberg, Switzerland, 2008, pp. 138–144.

- Niekamp, B.; Woś, Jucker A., Das Prunkkleid des Kurfürsten Moritz von Sachsen (1521–1553) in der Dresdner Rüstkammer: Dokumentation Restaurierung Konservierug, [The Magnificent Dress of Elector Moritz of Saxony (1521–1553) in the Dresden Armoury: Documentation, Restoration and Conservation], Abegg–Stiftung, Riggisberg, Switzerland, 2008, pp. 89–96.

- Miller, K.; Gatley, S. Keep Your Hair On: The Development of Conservation Friendly Wigs, Conservation Journal, 2011, Issue 59, pp. 2–3.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).