Submitted:

17 July 2024

Posted:

17 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

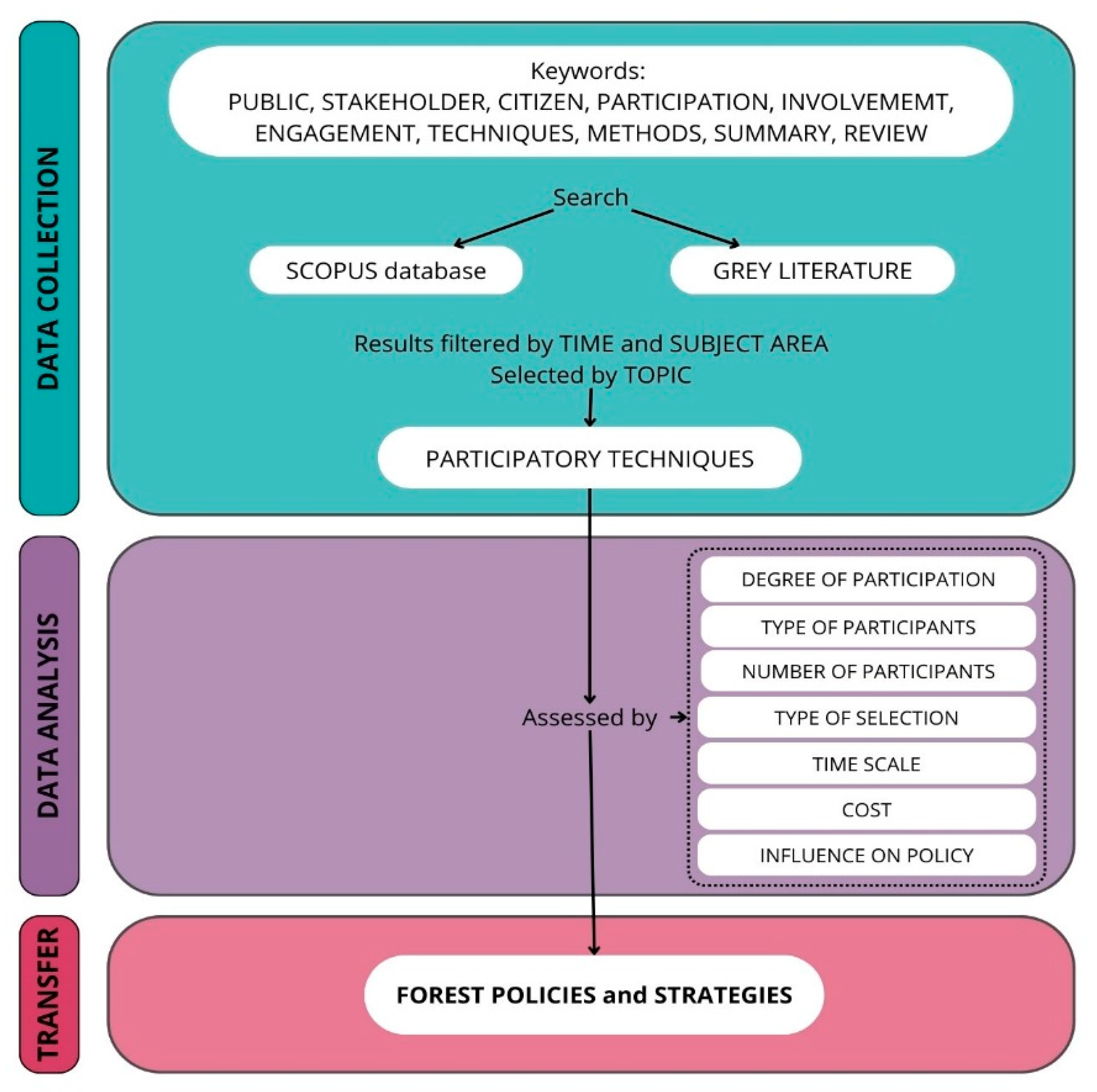

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Criteria to Assess Participatory Techniques

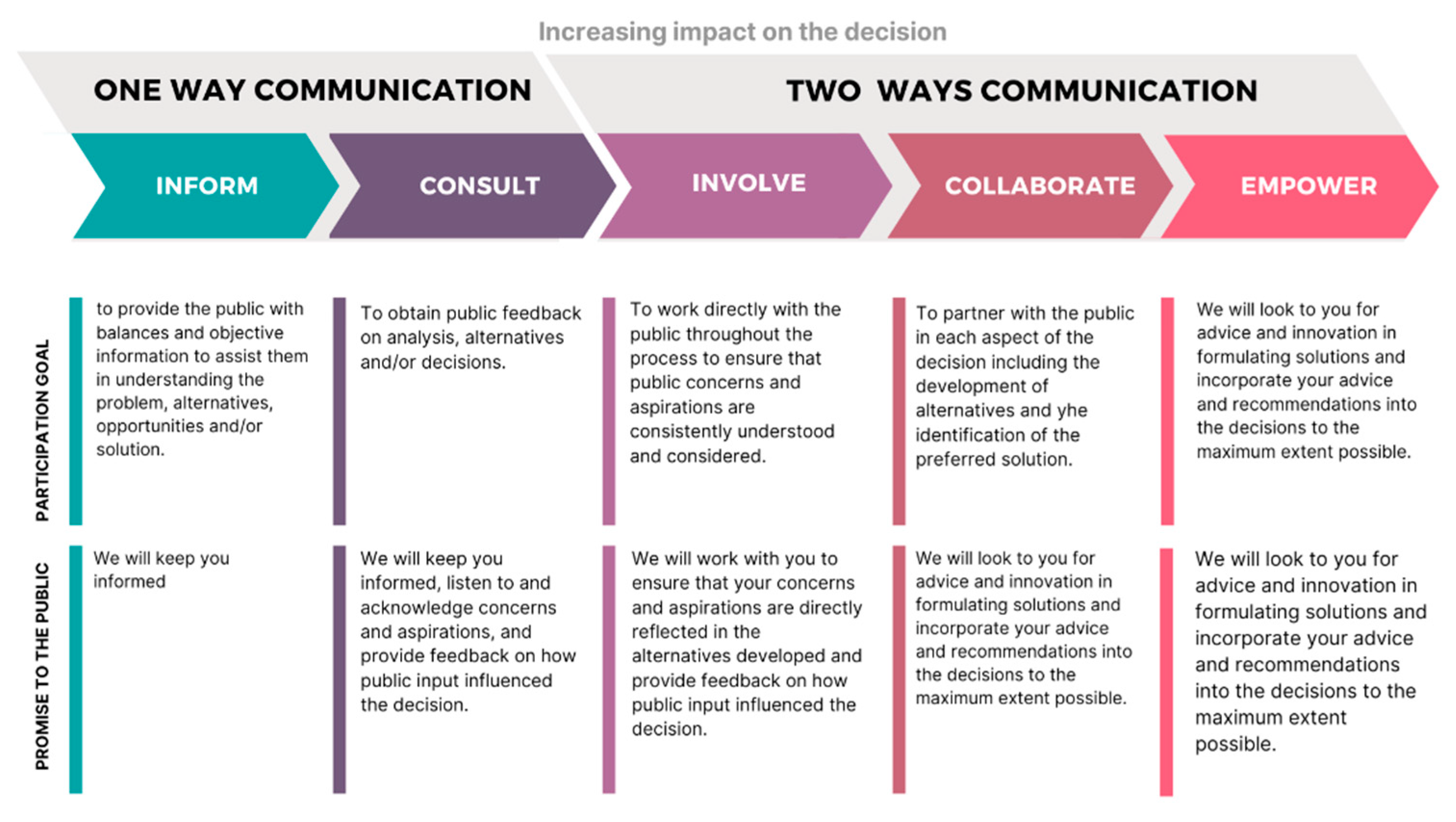

2.3.1. Degree of Participation

- Informing: providing balanced and objective information about new programs or services, and about the reasons for choosing them. Providing updates during implementation.

- Consulting: inviting feedback and suggestions on alternatives, analyses, and decisions related to new programs or services; possibly making adjustments and decisions according to their feedback.

- Involving: working directly with the public throughout the process to ensure that public concerns and aspirations are consistently understood and considered. Letting people know how their involvement has influenced decisions.

- Collaborating: enabling community members to participate in every aspect of planning and decision making for new programs or services. It means sharing responsibilities with citizens, working together, and making decisions collaboratively.

- Empowering: delegating of decision-making and giving the full managerial power over project development and implementation to the stakeholders/public.

2.3.2. Type of Participants

- Citizens: members of the community or public directly impacted by the decisions or issues being addressed. Their involvement can range from providing input and feedback to actively co-designing solutions.

- Stakeholders: individuals or groups who have an interest, involvement, or “stake” in a particular project, organization, or issue. Stakeholders can include local businesses, advocacy groups, government agencies, and non-profit organizations [35].

- Experts: professionals or subject matter experts who contribute specialized knowledge and insights to inform decision-making [36]. Experts may provide technical guidance, analysis, or recommendations based on their expertise.

- Policy-Makers: individuals or entities responsible for making final decisions based on the inputs and recommendations gathered through the participatory process. This could include elected officials, policy makers, or project managers [37].

- Supporting Figures: individuals who oversee and guide the participatory process to ensure that it runs properly, remains inclusive, transparent and productive (e.g., facilitators help manage discussions, encourage participation, and maintain a respectful environment).

2.3.3. Number of Participants

2.3.4. Selection of Participants

- Self-Selection: processes open to all stakeholders; those who participate have decided to do so consciously and by their own choice

- Random Sampling: recruitment can achieve a broad representativeness of participants through random sampling and thus reduce the prevalence of specific interests. One approach to ensure a better representativeness is to select a random stratified sample of the affected population [31].

- Targeted Selection: this form of selection is generally open to all stakeholders; however, to achieve a higher degree of representativeness among participants, individuals or representatives from various demographic groups are specifically invited to participate based on factors such as age, gender, education, or professional criteria [40].

2.3.5. Time Scale

2.3.6. Cost

2.3.7. Potential Influence on Final Policy

2.3.8. Transfer to Forest Policies

3. Results

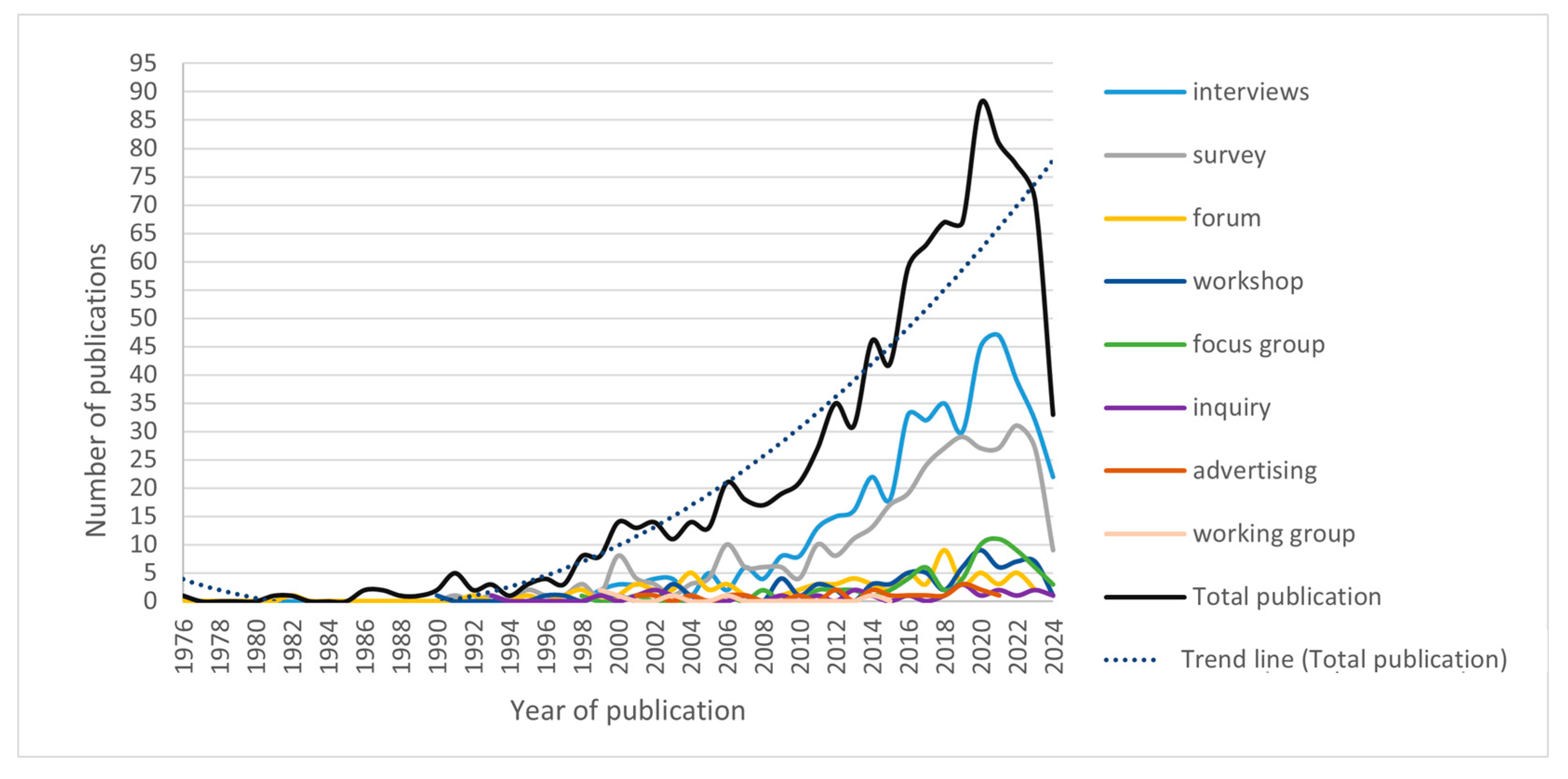

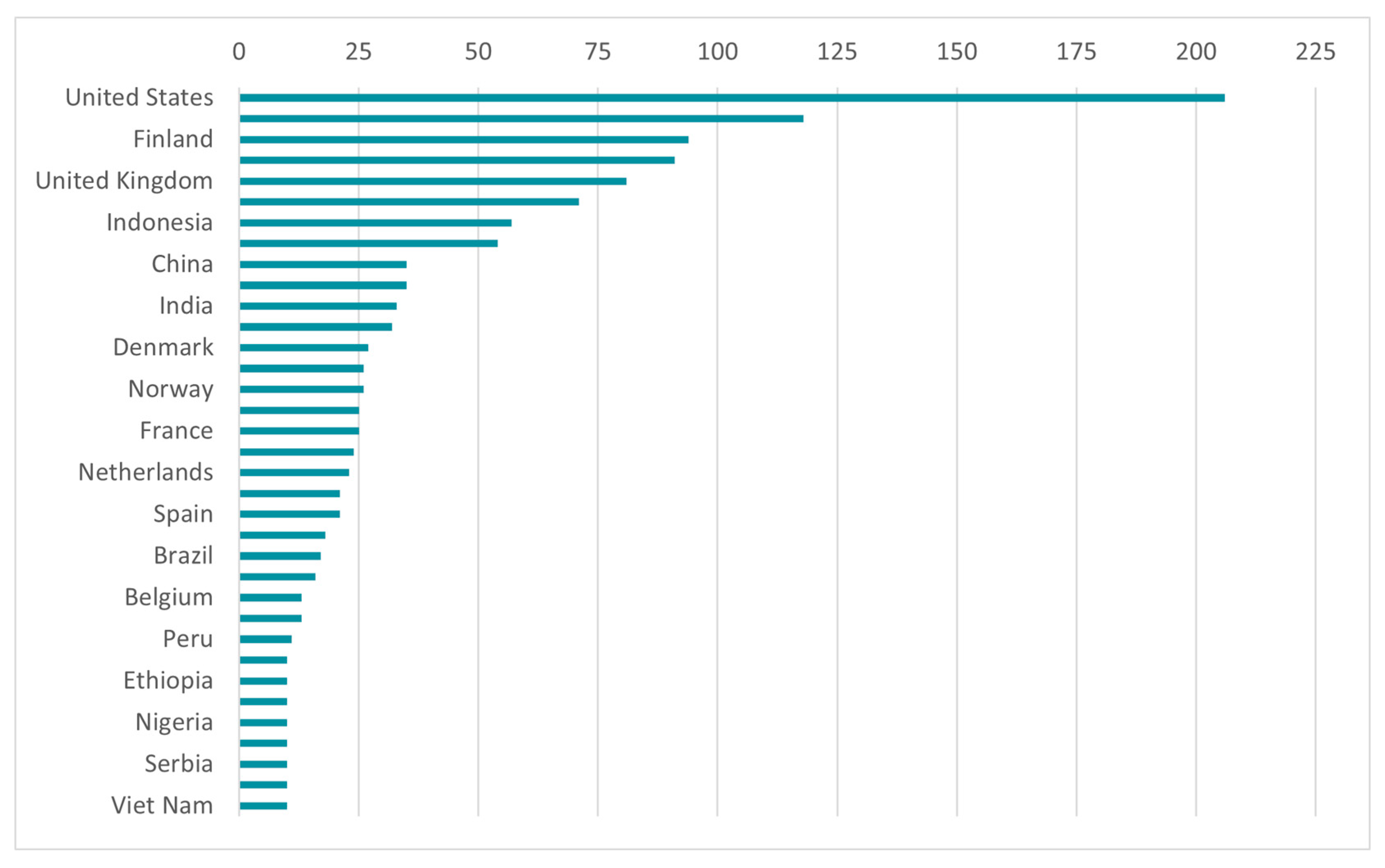

3.1. Results of Literature Review

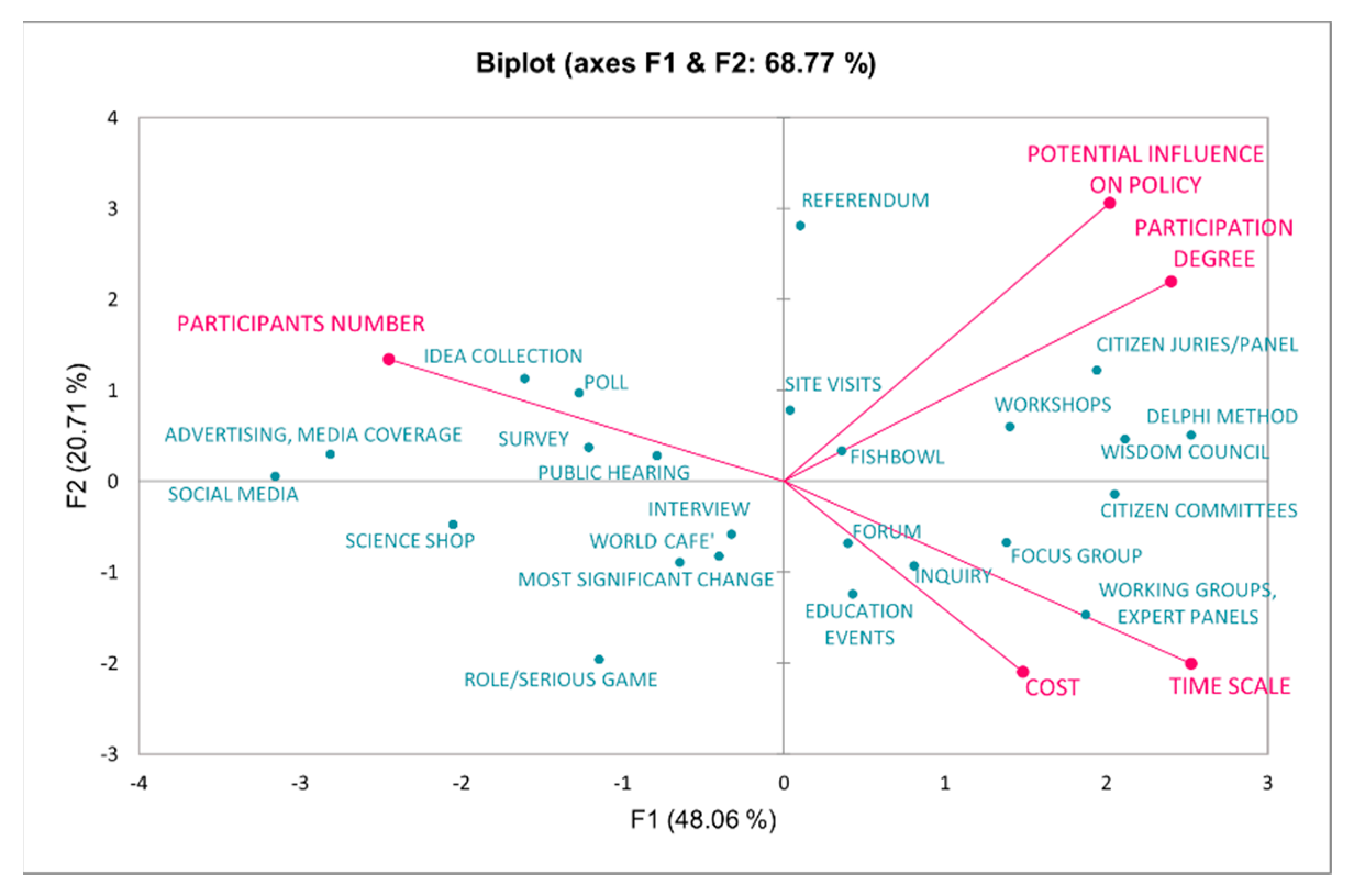

3.2. Assessment of Participatory Techniques

- the direct relationship between the degree of participation promoted and the potential influence of participatory power on policies. This relationship might seem easy to deduce, but in the real-world context, it is not straightforward. In fact, in many cases, influence on policies is not guaranteed, and in others, it can be indirect;

- the inverse relationship between the number of participants and the time scale. This relationship indicates that the greater is the number of people involved, the shorter is the time of participation usually required from each individual. Participatory techniques such as “Idea Collection/Crowdsourcing” and “Poll” are located along this vector, suggesting that they involve a large number of participants but require a short participation time.

3.3. Transfer to Forest Policies

4. Discussion

- the objective of the participatory process;

- the spatial scale of the process;

- the kind of information needed to develop the process.

- the kind and number of actors who should be involved more or less actively;

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pateman, C.; Participation and Democratic Theory. Cambridge University Press, 1970.

- Barber, B.R.; Participatory Democracy. The Encyclopedia of Political Thought. Wiley Online Library, 2014.

- Vitale, D. Between deliberative and participatory democracy: A contribution on Habermas. Philos. Soc. Crit. 2006, 32, 739–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bherer, L.; Dufour, P.; Montambeault, F. The participatory democracy turn: an introduction. J. Civ. Soc. 2016, 12, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Porta, D. Meeting democracy: Power and deliberation in global justice movements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Knopp T.B., Calbeck E.S. The role of participatory democracy in forest management. Journal of Forestry 1990, 88, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchy, M.; Hoverman, S. Understanding public participation in forest planning: a review. For. Policy Econ. 2000, 1, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttoud G., Solberg B., Tikkanen I., Pajari B.; The Evaluation of Forest Policies and Programmes. European Forest Institute (EFI), 2004, 52, 216.

- Cantiani, M. Forest planning and public participation: a possible methodological approach. iForest - Biogeosciences For. 2012, 5, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Cantiani, M.G.; De Meo, I. Public Participation in Forest Landscape Management Planning (FLMP) in Italy. J. Sustain. For. 2015, 34, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, N. Participation or involvement? Development of forest strategies on national and sub-national level in Germany. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 89, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hügel, S.; Davies, A.R. Public participation, engagement, and climate change adaptation: A review of the research literature. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2020, 11, e645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelstrand, M. Participation and societal values: the challenge for lawmakers and policy practitioners. For. Policy Econ. 2002, 4, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPF (Intergovernmental Panel on Forests), Report of the Ad Hoc Intergovernmental Panel on Forests on its fourth session/Commission on Sustainable Development, Fifth session. (UN DPCSD E/CN. 17/1997/12), 1997.

- Kouplevatskaya, I. The national forest programme as an element of forest policy reform: findings from Kyrgyzstan. Unasylva, 2006, 225, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Balest, J.; Hrib, M.; Dobšinská, Z.; Paletto, A. Analysis of the effective stakeholders' involvement in the development of National Forest Programmes in Europe. Int. For. Rev. 2016, 18, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication of 3 November 1998 from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on a Forestry Strategy for the European Union. In COM 1998/649 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. New EU Forest Strategy for 2030. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM, 572 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sandström, C.v, Pilstjärna M., Hannerz M., Sonesson J., Nordin A.; A One-Size-Fits-All Solution for Forests in the European Union: An Analysis of the New EU Forest Strategy. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N., Zhou, M., Dong, X., Qu, J., Gong, F., Han, Y., Zhang, L., 2020. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet, 2020, 395, 507-513.

- Atalan, A. Is the lockdown important to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic? Effects on psychology, environment and economy-perspective. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 2020, 56: 38-42.

- Sorsa, V.-P.; Kivikoski, K. COVID-19 and democracy: a scoping review. BMC Public Heal. 2023, 23, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes T., Adams L., Obijiaku C., Smith G.; Democracy in a Pandemic. Participation in Response to Crisis. London: University of Westminster Press, 2021.

- Silva Graça, M.; Lockdown Democracy: Participatory Budgeting in Pandemic Times and the Portuguese Experience. In: Lissandrello E., Sørensen J., Olesen K., Nedergård Steffansen R. (eds.), The ‘New Normal’ in Planning, Governance and Participation Transforming Urban Governance in a Post-pandemic World, Springer Charm, 2023, 111-124.

- Maas, F.; Wolf, S.; Hohm, A.; Hurtienne, J. Citizen Needs – To Be Considered. i-com 2021, 20, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, J., Participatory turn - and down-turn - in Finland's regional forest programme process. Forest Policy and Economics, 2018, 89: 87-97.

- Page, M.J.; E McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; A Akl, E.; E Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. Inst. PlanneRS 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.R.; Wentholt, M.T.A.; Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. Expert involvement in policy development: A systematic review of current practice. Sci. Public Policy 2013, 41, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. Public Participation Methods: A Framework for Evaluation. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2000, 25, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanz P., Fritsche M.; La partecipazione dei cittadini: un manuale. Metodi partecipativi: protagonisti, opportunità e limiti. Bologna: Regione Emilia-Romagna, Assemblea legislativa, 2014.

- Hotelling, H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J. Educ. Psychol. 1933, 24, 498–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association for Public Participation, Available online: https://www.iap2.org/ (Access:. 18.04.2024).

- Savini, F. The Endowment of Community Participation: Institutional Settings in Two Urban Regeneration Projects. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2011, 35, 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S., Graves A., Dandy N., Posthumus H., Hubacek K., Morris J., Prell C., Quinn C.H., Stringer L.C.; Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. Journal of Environmental Management, 2009, 90: 1933–1949.

- Linnerooth-Bayer, J.; Scolobig, A.; Ferlisi, S.; Cascini, L.; Thompson, M. Expert engagement in participatory processes: translating stakeholder discourses into policy options. Nat. Hazards 2015, 81, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S., Maule J., Papamichail N.; Decision behaviour, analysis and support. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- French, S.; Bayley, C. Public participation: comparing approaches. J. Risk Res. 2011, 14, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäck, A.; Friedrich, P.; Ropponen, T.; Harju, A.; Hintikka, K.A. From design participation to civic participation - participatory design of a social media service. Int. J. Soc. Humanist. Comput. 2013, 14, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krick, E.; Participant Selection Modes for Policy-Developing Collectives. In: Expertise and Participation. Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2021, pp. 137-161. [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Horlick-Jones, T.; Walls, J.; Pidgeon, N. Difficulties in evaluating public engagement initiatives: reflections on an evaluation of the UK GM Nation? public debate about transgenic crops. Public Underst. Sci. 2005, 14, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rough, J. Dynamic facilitation and the magic of self-organizing change. The Journal for Quality and Participation, 1997, 20, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Luyet, V.; Schlaepfer, R.; Parlange, M.B.; Buttler, A. A framework to implement Stakeholder participation in environmental projects. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 111, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannay, D. ‘Who put that on there … why why why?’ Power games and participatory techniques of visual data production. Vis. Stud. 2013, 28, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, C.; Aryal, K.P.; Edwards-Jonášová, M.; Upadhyaya, A.; Dhungana, N.; Cudlin, P.; Vacik, H. Evaluating participatory techniques for adaptation to climate change: Nepal case study. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 97, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geekiyanage, D.; Fernando, T.; Keraminiyage, K. Mapping Participatory Methods in the Urban Development Process: A Systematic Review and Case-Based Evidence Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, J.J. Participatory democracy: drawing on C. West Churchman's thinking when making public policy. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2003, 20, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, M.; Komendantova, N. Participatory environmental governance of infrastructure projects affecting reindeer husbandry in the Arctic. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 223, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijnik, M.; Mather, A. Analyzing public preferences concerning woodland development in rural landscapes in Scotland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 86, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dral, G.J.; Witte, P.A.; Hartmann, T. The impact of participatory decision-making on legitimacy in planning. disP - Plan. Rev. 2023, 59, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.J. Beyond radicalism and resignation: the competing logics for public participation in policy decisions. Policy Politi- 2017, 45, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Cubbage, F.W. Gender differences of participation in social forestry programmes in bangladesh. For. Trees Livelihoods 2003, 13, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, I. Participation Experiences and Civic Concepts, Attitudes and Engagement: Implications for Citizenship Education Projects. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 2, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Barreira, A.P.; Loures, L.; Antunes, D.; Panagopoulos, T. Stakeholders’ Engagement on Nature-Based Solutions: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, D.; Schweizer, P. Public values and goals for public participation. Environ. Policy Gov. 2020, 31, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; De Meo, I.; Garegnani, G.; Paletto, A. A multi-criteria framework to assess the sustainability of renewable energy development in the Alps. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 60, 1276–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werland, S. Global Forest governance—bringing forestry science (back) in. Forest Policy and Economics, 2009, 11, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słupińska, K.; Wieruszewski, M.; Szczypa, P.; Kożuch, A.; Adamowicz, K. Social Media as Support Channels in Communication with Society on Sustainable Forest Management. Forests 2022, 13, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, N. Beyond the Ladder of Participation: An Analytical Toolkit for the Critical Analysis of Participatory Media Processes. Crit. Perspect. Media Power Change 2018, 23, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participatory technique | Description | Tools for the application |

|---|---|---|

| ADVERTISING AND MEDIA COVERAGE | Channels used to inform audiences mainly visually. | Radio, newspapers, TV, websites, infographics, display, exhibits |

| CITIZEN COMMITTEES | Group of representatives from a particular community or a set of interests who are appointed to provide advice on an issue. The members meet regularly to provide ongoing input and advice throughout a project. | In presence or virtual meeting platforms |

| CITIZEN JURIES/PANEL | Deliberative process where a representative group of citizens is randomly selected to consider specific issues or policy questions. Participants engage in informed discussions guided by facilitators, review relevant information and work towards reaching a consensus or majority decision. The outcomes can inform policymakers and contribute to decision-making. | Round table, group in presence, virtual meeting tools |

| CITIZEN PROPOSALS/ IDEA COLLECTION | Gathering or soliciting ideas or suggestions from individuals or groups, for the purpose of generating solutions, innovation, or community engagement. | Online platforms, community meetings and forums, social media, blog or formal submission processes |

| DELPHI METHOD | A forecasting process and structured communication framework based on the results of multiple rounds of questionnaires sent to a panel of experts. After each round of questionnaires an aggregated summary of the last round is presented to the experts, allowing to adjust their answers according to the group response. | Online survey platforms, collaborative decision-making tools, video conferencing and webinar tools |

| EDUCATION EVENTS | Organized activities like workshops, seminars, or conferences to share knowledge and facilitate learning among participants. The key aspect is active interaction, where participants are encouraged to participate in discussions and apply the knowledge gained to their own contexts. | Workshops, seminars, or conferences in presence; it can be associate with virtual meeting and webinar platforms |

| EXPERT PANELS | A variety of experts are engaged based on various fields of expertise to debate and discuss various courses of action. Experts make recommendations on complex issues, projects, policies, or research questions based on their expertise to inform decision-making and problem-solving processes. | Round tables, virtual meeting tools, platforms |

| FISHBOWL | Meeting where a small number of participants sit in a circle or central area engaging in a structured conversation while others observe from outside listening and taking notes. | In presence eventually with audience engagement tools, digital collaboration platform |

| FOCUS GROUP | Collection of data through group interaction. The group comprises a small number of carefully selected people who discuss a given topic. Focus groups are used to identify and explore how people think and behave, and they throw light on why, what and how questions. | Face to face, virtual tools |

| FORUM | Structured event where citizens and experts come together to discuss, exchange ideas, and engage in dialogue on specific topics of interest to facilitate information-sharing, collaboration, and collective problem-solving promoting community engagement. When the focus is on a complex societal issue and the goal is to achieve a consensus or shared understanding, they are called 'Consensus Conference'. | Town hall meetings, conferences, online platforms, open forums including presentations, panel discussions; mixed forms online and in presence |

| INQUIRY | Conducting investigations or research activities where participants are actively involved in defining research questions, gathering and analysing data, interpreting findings, and co-creating knowledge. | Face to face; using virtual tools |

| INTERVIEW | Structured conversations between an interviewer and one/ more participants with the goal of gathering insights, knowledge, opinions, or perspectives on a specific topic or issue which contributes to the process of research, decision-making, or problem-solving. | Depending on the format (one-on-one, group interviews, or focus group); face to face or with virtual tools |

| MOST SIGNIFICANT CHANGE | Stories of significant change are collected, systematically selected and then reviewed and analysed to identify key themes, trends, and impacts. Insights into the outcomes and effectiveness of the program from the perspective of those directly affected are provided. | Interviews recorded as audio or video or note-taking, reporting forms; selecting the stories by voting or scoring |

| POLL | Quick collection and immediate responses from a sample of people on a specific question or topic. Closed-ended questions are used with predefined choices to collect quantitative data and gauge public opinion/preferences efficiently. | Physical polling booths, interactive Displayspostal vote, SMS, email, online vote: social media, community engagement platforms |

| PUBLIC HEARING /MEETING |

Formal presentation opens to the general public, conducted by an agency, regular authority or organizers regarding plans. Public may voice opinions but has no direct impact on recommendation. | Town-hall meeting, panel roundtable, virtual meeting platforms, presentation followed by questions |

| REFERENDUM | Direct vote by the electorate on a particular proposal, law, or constitutional amendment. Referenda are used to seek public approval or rejection of a specific decision or policy, allowing citizens to directly influence outcomes. | In person |

| ROLE/SERIOUS GAME | Participants assume specific roles or characters to engage in simulated scenarios, often used for educational or problem-solving purposes to explore decision-making and interactions in a realistic and interactive setting. | In presence, virtual tools |

| SCIENCE SHOP | Offers citizens groups free or very low-cost access to scientific and technological knowledge, to help them achieve social and environmental improvement. These organizations mediate between citizen groups and research institutions, and conduct their own research projects, based on requests received from citizen groups. | In presence or virtual tools, e-mail |

| SITE-FIELD VISITS/TOUR | Visits to physical locations relevant to a project, issue, or study, are organized with the purpose of engaging participants directly in the context of the subject matter. | Opening up a project venue for the public to visit; tour associated with a conference or workshop |

| SOCIAL MEDIA | Platforms possibly used to actively inform, engage communities, and towards more interactive and user-driven experiences. | Social media platforms |

| SURVEY | Data collection method aimed at building knowledge on a specific group and topic, with data collected through a population sample targeted by the intervention. Surveys often use a combination of closed-ended and open-ended questions. | Paper survey, telephone, postal survey, SMS, email, online survey, social media, mobile survey app; |

| WISDOM COUNCIL | A small group with a mix of all hierarchical levels, departments and activities. The group has the task of identifying and working on urgent issues for the organization. In a few days they develop theses and recommendations for the urgent issues. | In presence or virtual meeting platforms |

| WORKING GROUP | Stakeholders or representatives from different organizations collaborate to address specific tasks, projects, or issues. The group works together to achieve defined objectives, such as developing strategies, making decisions, implementing plans, or solving problems within a focused timeframe. | Round tables, virtual meeting tools, open innovation digital platforms: collaborative editing tools and file sharing, video conferencing |

| WORKSHOPS (mind mapping) | A structured session where participants actively engage in discussions, exercises, and hands-on activities related to a specific topic or objective with the help of a facilitator. Workshops encourage participation, interaction, and group dynamics to achieve learning outcomes, generate ideas, maps, explore solutions, or develop skills. | Face to face, virtual tools |

| WORLD CAFE' | Hosting structured conversations in a café-like setting to facilitate dialogue and idea-sharing among participants. This method encourages informal, open discussions in small groups, with participants moving between tables to exchange perspectives on a common topic. | Face to face with available material for annotation |

| DEGREE OF PARTICIPATION |

PERSONS INVOLVED | NUMBER OF PARTICIPANTS | SELECTION OF PARTICIPANTS | TIME SCALE | COST | POTENTIAL INFLUENCE ON POLICY | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TYPE OF PARTICIPANTS | SUPPORT STAFF | DURATION | PERIODICITY | ||||||

| ADVERTISING, MEDIA COVERAGE | INFORM | citizens | - | large groups (> 100) | no selection | variable | single event | moderate | low |

| SOCIAL MEDIA | INFORM/ CONSULT |

citizens | - | large groups (> 100) | no selection/ self-selection |

variable | single event | low | moderate, liable to be indirect |

| PUBLIC HEARING/MEETING | INFORM /CONSULT |

citizens | supporting figure, policy maker | large groups (> 100) | self-selection | no longer than 2 hours | single event (sometimes periodic) | low/moderate | low, moderate |

| ROLE/SERIOUS GAME | INFORM /CONSULT |

citizens, stakeholder | tools' dependents | variable depending on the chosen tool, also large groups (> 100) |

self-selection/ targeted |

few hours, variable (also depends on tool) | single event | potentially high | low, not guaranteed |

| SURVEY | CONSULT | citizens, stakeholder | tools' dependents | large groups (> 100) | random/targeted | several minutes | single event (sometimes repeated) | potentially high | indirect and difficult to determinate |

| IDEA COLLECTION | CONSULT | citizens | tools' dependents | variable, large groups (>100) | self-selected | variable | periodic | low | variable but not guaranteed |

| INQUIRY | CONSULT | expert | supporting figure | small group (<25) | targeted | approximately one hour | single event | moderate | moderate, liable to be indirect |

| INTERVIEW | CONSULT | expert | supporting figure | small group (<25) | targeted | approximately one hour | single event | low/moderate | low/moderate |

| MOST SIGNIFICANT CHANGE | CONSULT | stakeholder | supporting figures | medium-sized groups (25 to 100) |

targeted | around 2 days a month for session; more months | periodic | potentially high (time consuming) | low/moderate |

| SCIENCE SHOP | CONSULT | citizens, expert | expert | large groups (> 100), variable |

self-selection | variable | periodic | moderate | variable but not guaranteed |

| FORUM | CONSULT /INVOLVE |

citizens, stakeholder | decision maker, expert, supporting figure | medium-sized groups (25 to 100) |

self-selection | 1-5 days, weeks (preparatory meetings) | single event (sometimes periodic) | moderate to high | moderate, variable but not guaranteed |

| SITE-FIELD VISITS/TOUR | CONSULT/ INVOLVE |

stakeholder, expert | expert | medium-sized groups (25 to 100), variable |

self-selection/ targeted | 2-4 hours | single event (sometimes periodic) | low | moderate, not guaranteed |

| EDUCATION EVENTS | CONSULT/ INVOLVE |

citizens | expert | large groups (> 100) | self-selection | 1 day or multi-days event | single event | potentially high, variable | moderate |

| FOCUS GROUP | CONSULT/ INVOLVE |

stakeholder | supporting figure | small group (<25) | targeted | usually up t 2 hours | single event | potentially high | moderate but liable to be indirect |

| FISHBOWL | INFORM/CONSULT /INVOLVE |

citizens, stakeholders, expert, policy makers | supporting figure | medium-sized groups (25 to 100) |

self-selection and targeted | 15-20 minutes each thread, total 1-2 hours | single event | low/moderate | moderate |

| WORLD CAFE' | CONSULT/ INVOLVE |

citizens, stakeholder | supporting figure, expert | medium-sized groups (25 to 100), variable (also hundreds) |

self-selection, targeted | 20-30 minutes to talks; one day (1-4hours) or series of events | single event | low to high, variable (number of participants involved) | low, variable but not guaranteed |

| POLL | INVOLVE | citizens, stakeholder | - | large groups (> 100) | random | a few minutes | single event, sometimes periodic (weeks for deliberative polling) | potentially high | low/moderate, indirect and difficult to determinate |

|

WORKIN GROUPS, EXPERT PANELS |

INVOLVE | expert | supporting figure | small group (<25) | targeted | from a few hours to events on several days | periodic (3-18 months) | moderate to high | moderate, variable but not guaranteed |

| WORKSHOPS | INVOLVE, COLLABORATE |

(citizens)/stakeholders | expert, supporting figure | medium-sized groups (25 to 100) , variable |

targeted | from half a day to 5 days | single event | moderate to high, variable | variable but not guaranteed |

| CITIZEN COMMITTEES | INVOLVE/ COLLABORATE |

citizens | - | small group (<25) | random/targeted | 1-2 days | periodic | variable | variable but not guaranteed |

| DELPHI METHOD | COLLABORATE | expert | supporting figure | medium-sized groups (25 to 100) |

targeted | approximately one hour | periodic, more rounds (weeks/month) | moderate to high (expert and material) | liable to be indirect, but potentially high |

| WISDOM COUNCIL | COLLABORATE | citizens | supporting figure | small group (<25) | random | 1-2 days | periodic | moderate | variable but not guaranteed |

| CITIZEN JURIES/PANEL | EMPOWER | citizens, (recruited experts) | supporting figure | small group (<25) | random | 4-7 days | single event | moderate to high | high, variable but not guaranteed |

| REFERENDUM | EMPOWER | citizens | - | large groups (> 100) | self-selection | minutes | single event | variable/low | high |

| Variables | PARTICIPATION DEGREE | PARTICIPANTS NUMBER |

COST | POTENTIAL INFLUENCE ON POLICY | TIME SCALE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PARTICIPATION DEGREE | 1 | -0.355 | 0.138 | 0.573 | 0.452 |

| PARTICIPANTS NUMBER | -0.355 | 1 | -0.210 | -0.304 | -0.657 |

| COST | 0.138 | -0.210 | 1 | 0.190 | 0.337 |

| POTENTIAL INFLUENCE ON POLICY | 0.573 | -0.304 | 0.190 | 1 | 0.171 |

| TIME SCALE | 0.452 | -0.657 | 0.337 | 0.171 | 1 |

| PARTICIPATORY METHOD | NUMBER OF RESULTS | YEAR OF FIRST PUBLICATION | YEAR OF LAST PUBLICATION |

|---|---|---|---|

| INTERVIEWS | 452 | 1976 | 2024 |

| SURVEY | 365 | 1988 | 2024 |

| FORUMS | 78 | 1982 | 2023 |

| WORKSHOP | 74 | 1990 | 2024 |

| FOCUS GROUP | 69 | 1998 | 2024 |

| INQUIRY | 24 | 1993 | 2024 |

| ADVERTISING, MEDIA COVERAGE | 20 | 2001 | 2021 |

| WORKING GROUPS/EXPERT PANEL | 10 | 1999 | 2021 |

| PUBLIC MEETING/HEARING | 8 | 1999 | 2024 |

| SITE-FIELD VISITS/TOUR | 8 | 2005 | 2021 |

| SOCIAL MEDIA | 7 | 2019 | 2022 |

| DELPHI METHOD | 6 | 2001 | 2021 |

| REFERENDUM | 6 | 2004 | 2020 |

| MOST SIGNIFICANT CHANGE | 5 | 1998 | 2023 |

| POLL | 5 | 1976 | 2019 |

| ROLE/SERIOUS GAME | 2 | 2018 | 2023 |

| CITIZEN COMMITEES | 1 | 2012 | 2012 |

| CITIZEN JURIES/PANEL | 0 | - | - |

| EDUCATION EVENTS | 0 | - | - |

| FISHBOWL | 0 | - | - |

| IDEA COLLECTION/ CROWDSOURCING IDEAS | 0 | - | - |

| SCIENCE SHOP | 0 | - | - |

| WISDOM COUNCIL | 0 | - | - |

| WORLD CAFE | 0 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).