Introduction

“The past is a foreign country: They do things differently there.” So said LP Hartley in the opening lines of his book “The Go-Between”. Whilst it is universally acknowledged that the work and life of a junior doctor has changed dramatically over the past 50 years, the precise details of this past are often piecemeal, ethereal or half remembered. Handed down from surgical generation to generation via family or friends and often with the prefix “back in my day…”. But was the life of a junior doctor half a century ago, working in the same department, objectively better or worse than today? One view is that in the “good old days” patient care was better, doctors were more respected (and possibly more respectable) and although you worked hard, you played hard. Conversely, the very reasons for introduction of measures such as enforced rest periods and shift-based work patterns are the proven dangers of over-worked, under-rested doctors. But which of these viewpoints is correct, and does it matter whom you ask?

The life of a junior doctor (Senior House Officer, SHO/FY2) in one UK-based burns service in 1970 was explored through a first-hand account with a junior doctor of that time, and accompanied by a review of available literature. A contrast was then made with life today in the same unit, and presented to healthcare workers within the burns centre. The question was posed: “Would you rather be a burns SHO in 1970 or now?” With the aim of determining whether today’s staff really believed that life was better in the “good old days”.

Methods

Setting

Today, the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, is home to the Midlands Burn Care Network’s regional burn service. Comprising a 15 bed adult burns centre, theatre and critical care unit which can house a further four critically ill burns patients are adjacent. Children are treated at the nearby Birmingham Children’s Hospital in the regional children’s burns centre. This comprises a further seven inpatient beds and an adjacent burns theatre and critical care unit to house ventilated patients. Both services have operating lists five days a week. Seven full time consultants cover across both sites, with junior doctor cover provided by a mixture of burns fellows, and plastics registrars and FY2/SHOs. The new Queen Elizabeth Hospital was built in 2010, but the home of the burns centre in 1970 for both adults and children was the Birmingham Accident Hospital (BAH) (

Figure 1).

The BAH (commonly referred to as “The Acci”) is widely considered to be the world’s first trauma centre. The Medical Research Council (MRC) Burns and Industrial Injuries Unit within the BAH was formed in 1944, before the creation of the NHS in 1948 (Hardwicke J). It has a rich and colourful history, which has been well documented with written and photographic archives. The model of centralised burns care established here by Mr Douglas Jackson and colleagues in the 1960s and 70s has been key to the design of the national burns service in place today. The burns unit established here moved in 1993 to Selly Oak, before finally moving to its current sites at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital and Birmingham Children’s Hospital.

During the lifespan of the burns service in Birmingham, there has been massive change in the scientific understanding and medical practice of burns care. There has also been much wider political, economic and social change within the nation that it serves. These factors mean the life of a junior doctor working within the burns unit has evolved, with wide ranging differences from working hours and conditions, dress, pay and living standards, in addition to the care administered to burns patients.

The Interview

A semi-structured interview was carried out with a retired surgeon by a current SHO/FY2 doctor. A general discussion was followed by 30 closed questions designed to ascertain in detail what an average working week looked like. Details were verified if possible with existing records at the time, and comparisons were made between the experience of the present day SHO/FY2 (

Table 1).

Poster Dissemination and Survey

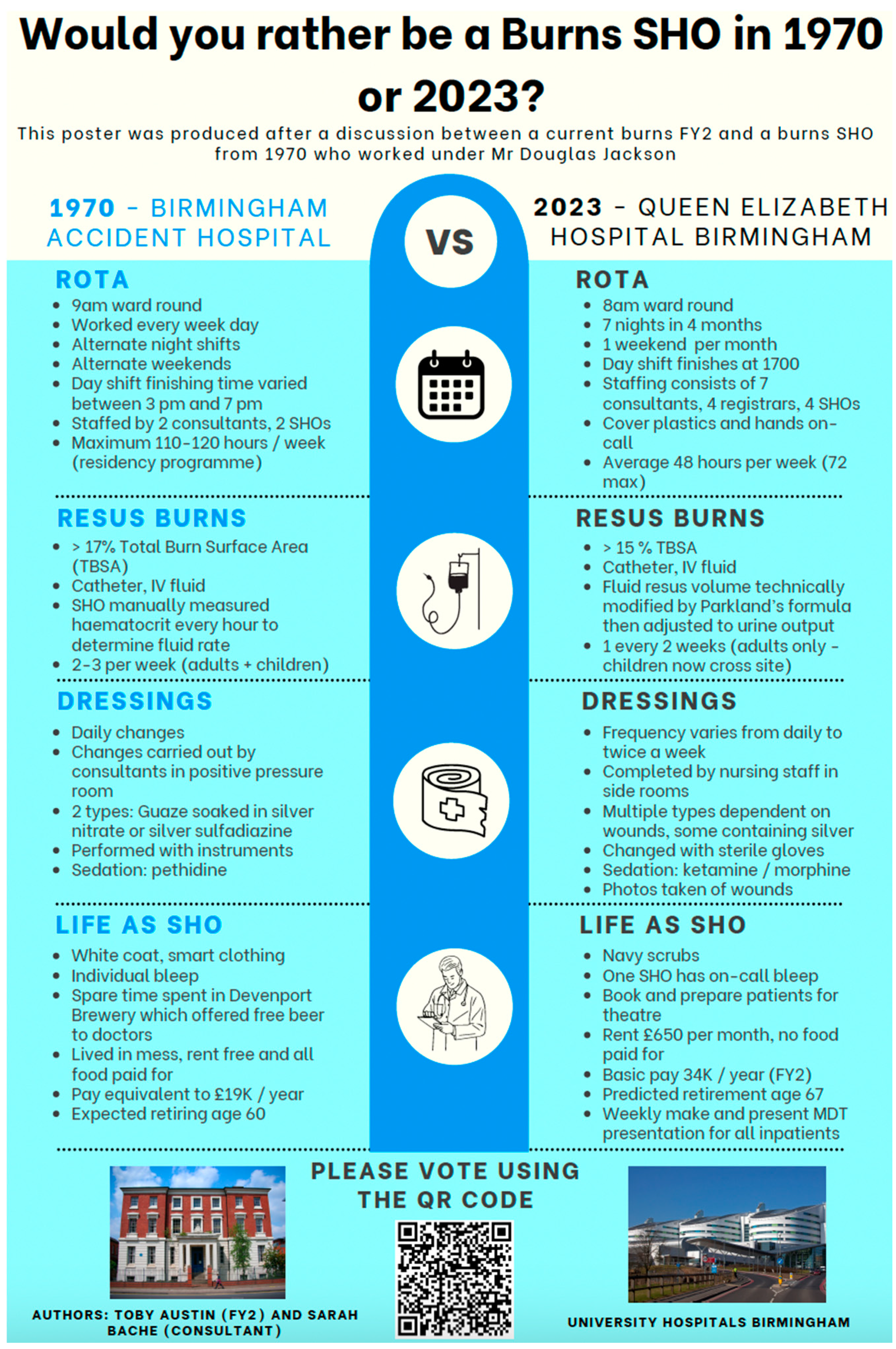

The key points raised in the interview were summarised in a poster (

Figure 2). This was displayed in communal areas on the burns centre and disseminated to training and consultant level doctors via group communications platforms (Email and WhatsApp). The poster featured a QR code linking to a survey that was open to all (including allied health care professionals) featuring a series of questions about the person answering including age and personal experience. The key question posed by the survey was “Would you rather be an SHO in 1970 or 2023?”. Data from the survey was gathered using Microsoft Excel, and statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS version 29.0.2.0. Student’s unpaired T-test was performed to demonstrate if there was a difference in age between those who voted for each group. Binary logistic regression and chi-squared test was carried out in addition to examine for relationship between age, gender and prior burns experience at SHO/FY2 level. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

The Interview

The interview begins with the lament: “The world has b****y changed…”. In 1970 the world did indeed look very different: Just the year prior man had first walked on the moon and Concorde took its first test flight. In early 1970, the interviewee, then in his 20s, began his three month burns rotation as one of two “house surgeons” for Mr Douglas MacGregor Jackson and Mr Jack Cason, the only two appointed consultants at the 30 bed Birmingham Accident Hospital burns unit. With no registrars, he directly reported to them. He describes his average working week.

Waking in the doctor’s accommodation in which, without exception, all junior doctors lived, the interviewee dons his freshly washed and pressed white coat and places his personal bleep in his pocket. He is on call today, as he will be for at least eight hours, every working day of this job. He will also be on call every other night and every other weekend, averaging around 106 hours a week. The accommodation is however provided free of charge for all house officers, in addition to food, drink (notably unlimited beer, piped directly into the ubiquitous doctors’ mess bar from the next-door Davenport’s brewery) and laundry services.

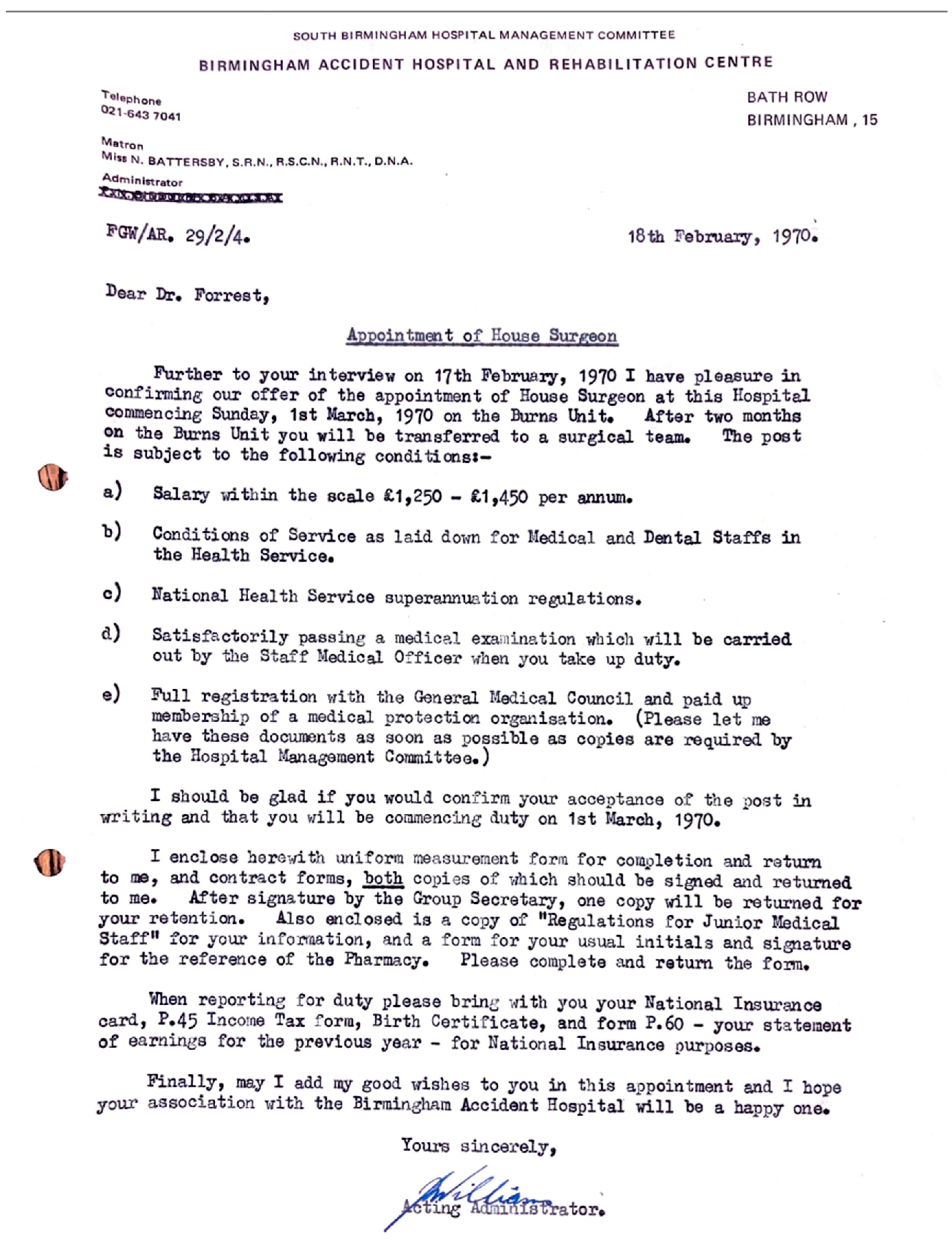

“I wore a white coat every single day from my start right up to my retirement in 2007. Fresh daily, identifiable and smart. I resented its demise.” With regards to remuneration, the House Officer received £1,350 per annum (

Figure 3) which he thought at the time was a “princely sum”.

He prepares notes and blood results and awaits with the matron the arrival of the “tall, elegant and always well turned out” Mr Jackson. “We used to start the ward round with a prayer” he recalls. Bowing their heads at 9am, they pray for the health of their patients. He goes on to describe a somewhat familiar pattern of work to today’s burns SHOs: A ward round, bloods, intravenous access, the vigilant monitoring patients with large burns, silver nitrate-based dressing changes, all interrupted occasionally with new referrals from the Accident and Emergency (A & E) department. Perhaps surprisingly, in contrast to today’s mainly nurse-led service, dressing changes were strictly performed by consultants. Within a positive pressure room, dressings were changed daily with sterile instruments, and intravenous pethidine as sedation. He would attend theatre at least twice a week to act as surgical first assistant.

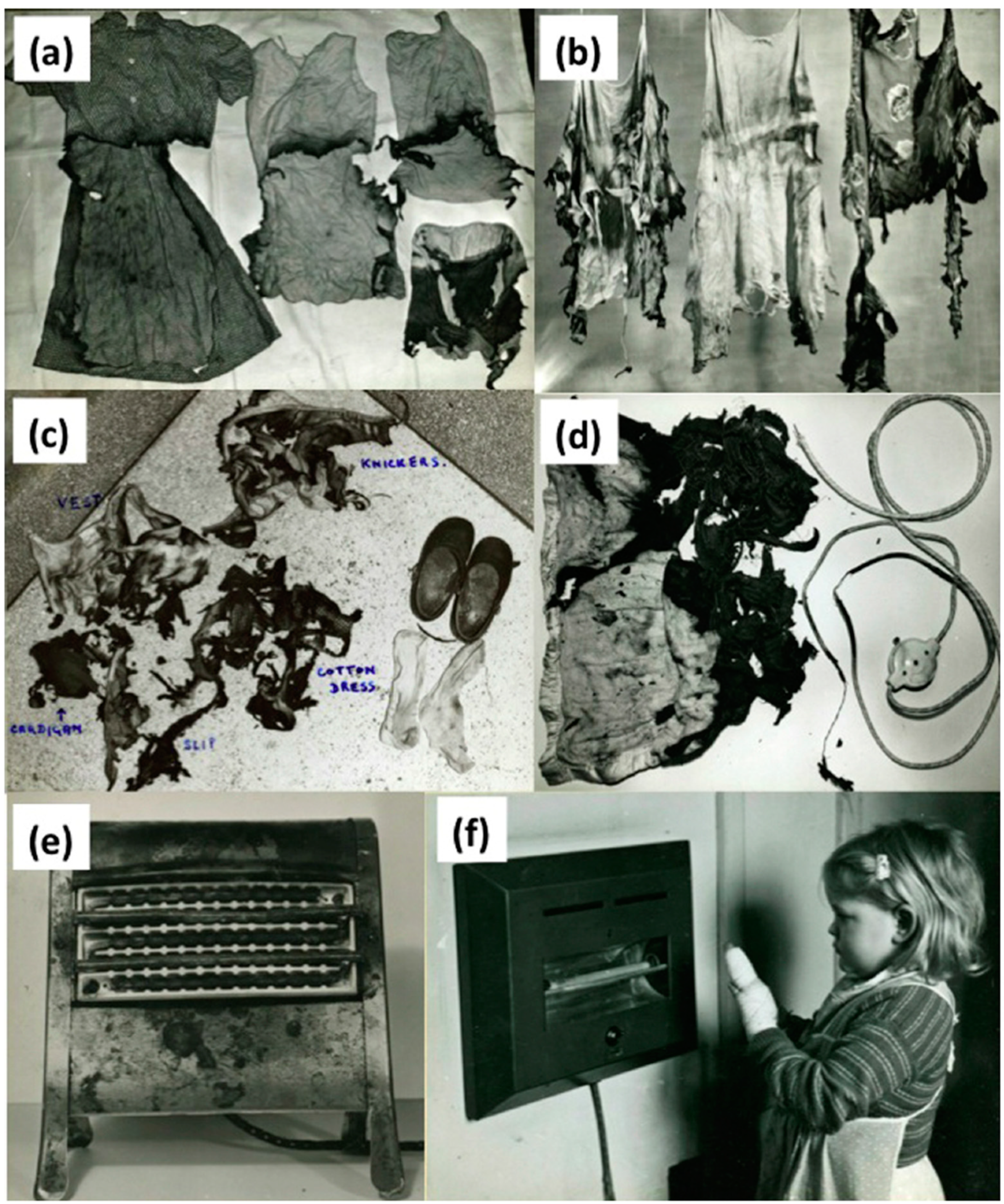

For new referrals, a doctor from A & E would find the on call SHO personally. The interviewee remembers an average of two “large” burns a week. This is possibly more than the present day burns service in Birmingham, although comparisons are difficult due to different thresholds for resus burns, and the separation of adult and paediatric sites. However, the number of major burns is steadily declining despite the city’s population more than doubling in the intervening period, predominantly due to the impact of health and safety legislation. A publication by Jackson from the time describe a different aetiology to that which we see today, with a predominance of burns resulting from coal fires, electric heaters or paraffin heaters (

Figure 4) (D Jackson & 25). In comparison, a recent review of the aetiology of patients who presented to the unit over the last decade showed scalds and flame burns being the predominant causes (unpublished data). The interviewee similarly describes the commonly encountered causes of paediatric burn injuries from three bar electric heaters and clothing ignition, mechanisms that are thankfully much less common today.

There are stark differences in the delivery of bad news. Specifically, he recounts the full name of a 10-year-old girl with what was considered to be a futile 75% total body surface area (TBSA) scald injury. After all this time he becomes visibly moved as he recalls her mother being told by a doctor, shortly after admission, in a brisk matter of fact way, “She’s going to die you know”.

With regards to life outside of the hospital during this period, the doctors’ mess and bar is where most socialising would occur. Shockingly, use of the free bar was not exclusively for those off duty. However, “weekends off” would tend to begin at 3pm on Saturday, with a return to the hospital by 10pm on Sunday, ready for the next working week.

The Comparison

Working Patterns

The interviewee paints a clear picture of his life and work in 1970, and his account may resonate with many who also worked during this period. What is perhaps most striking initially, is how many working hours was normal during this period.

In 1970, his average working week of over 100 hours contrasts sharply with today’s SHO/FY2 working a maximum 48 hour week. This live-in existence was a tradition for many decades prior to this. Notably, Professor Harrold Ellis recalls in the late 1940s he would have to “…see emergency patients in my pyjamas, underneath my white coat” (White C. Was there ever a golden age for junior doctors? BMJ 2016; 354 i3662). This workload necessitated living in-house, hence “house officer” (often in those days “houseman”), or “house surgeon”). The gruelling demand of this workload did not go unprotested, with the first junior doctor strike conducted by the BMA in 1975, calling for reduced working hours and more equitable pay. Eventually the subsequent change was facilitated by the introduction of the European Working Time Directive in 1998, which was fully implemented for junior doctors by 2009. This legislation has facilitated the introduction of protected time “off-duty” around on call shifts, with an aim of safer conditions for doctors and patients.

High intensity of work was, and may still be believed by many to be offset against greater clinical experience, better comradery with colleagues, and seamless continuity in patient care. However, of those working as junior doctors in the 1970s retrospectively cited these long hours to have a significant impact on their long-term health, happiness and family life (Smith F, Goldacre MJ, Lambert TW. Adverse effects on health and wellbeing of working as a doctor: views of the UK medical graduates of 1974 and 1977 surveyed in 2014. J R Soc Med. 2017 110(5):198-207). The concept of burnout was not even described until 1974 (Freudenberger & 30). By 2017, rates of emotional burnout amongst UK doctors were reported to range from 31 – 54%, with overload and increased hours worked being some of the factors cited (Imo UO. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among doctors in the UK: a systematic literature review of prevalence and associated factors. BJPsych Bull. 2017; 41(4):197-204).

Finances

The interviewee reports by means of his original letter of appointment (

Figure 3) pay of between £1250 – £1450. Taking the median figure of £1350, and using historical inflationary data gathered by the retail price index, this is equivalent to £17,832 (March 2024). The Rt Hon. Mr Willie Hamilton, Labour Member of Parliament for West Fife in a supplementary debate on the “Junior doctors pay dispute” (history does tend to repeat itself) lays out the pay scales (House of Commons Archive - Doctors and dentists pay. HC Deb 21 July 1970 vol 804 cc419-40) (

Table 2).

Direct salary comparison to the most junior doctor (SHO) working in our burn unit today however is challenging. Firstly, the present day most junior member of the burns team is an SHO/FY2, opposed to a house officer, so at least a year senior. Secondly, the financial burden of accommodation and essential bills was non-existent for most junior doctors in 1970. Mess culture meant that unlike todays SHO in our unit, there was no cost for accommodation, meals, council tax, heating, electricity and commuting. The exact value of all this is difficult to estimate due to individual variation in spending habits. However, using UK average household expenditure on rent bills and food to guide us, this would be in the region of £14,000-£18,000 per annum. It is worth noting that payment for these goods and services today come after being subjected to income tax, making the true cost of this benefit-in-kind even higher than this figure.

In 1970, the average house price (£3920) was 3.1 times higher than average earnings, which starkly contrasts with today’s house prices being 8.39 times average earnings today, and average prices of £285,431.

Finally, whilst in depth discussion about the pension system is also outside the scope of this article, the retirement age if you were a junior doctor in 1970 was 60 years old and on a final salary pension. For everyone born after 1978 the current state pension age is 68 years old and pensions are based on average salary. This figure may need to further rise to 71 years old by 2050, according to some independent think tanks in order to support the economic model of retirement in the UK.

Workload and Burns Care

Like all areas in trauma care, burns management has seen great advancements and changes over the last 50 years. This has culminated in an increase of the threshold of expected survivability in major burns. Today, a child with 95% TBSA burns may not be considered futile, let alone 70% TBSA as described in the interview.

There are many elements of burns care that have bought about this change, but perhaps the most significant of which is the concept of early tangential excision, first reported by Zora Janžekovič in the 1960’s (1970 & 10(12):1103-8; Freudenberger & 30; House of Commons Archive - Doctors and dentists pay. HC Deb 21 July 1970 vol 804 cc419-40; Imo UO. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among doctors in the UK: a systematic literature review of prevalence and associated factors. BJPsych Bull. 2017; 41(4):197-204; Roberts & 72(1)). Although not an established routine part of burns care in the UK in 1970, Jackson was an early proponent of tangential excision and immediate split skin grafting of deep dermal burns (D Jackson & 25). Indeed, the interviewee recalls Mr Jackson being invited to America to speak about his experience. This, combined with the famous Jackson’s zone of injury model of burn wounds means the recollections of the doctor working in Birmingham at this time provide a unique insight into the centre at a time of immense change from the traditional practise of allowing the burn to “slough and separate” over four to six weeks. The acceptance of early excision of burn wounds, alongside improved fluid resuscitation, infection control organ support, and management of the hypermetabolic response have all helped to reduce mortality from major burns in the last 50 years (Roberts & 72(1)).

The population that today’s burns centre serves has more than doubled in the intervening 50 years and yet, the number of beds in the unit have halved, as have the number of resuscitation burns presenting to it. Meanwhile the number of doctors delivering the service today has risen from 4 to 15. From photographic archives that exist, we can see that the problem of burn causation was well known and documented in the 1960s, and was key to the implementation of health and safety legislation that have been the predominant drive for this reduction. The medical complexity, and age of patients presenting with burns has however increased over time (Brusselaers N & 31(12):1648–1653; D Jackson & 25).

Survey

In total 76 people completed the survey:66 responders were doctors, the rest made up by allied health care professionals (HCP). Of doctors, 24% (n=16) were consultants, 18% (n=12) registrars, 36% SHOs (n=24) and 21% (n=14) foundation year one (FY1) with a broad range of ages from 23 to 60. Over half, (53%) of doctors had worked as an SHO/FY2 on a burns unit.

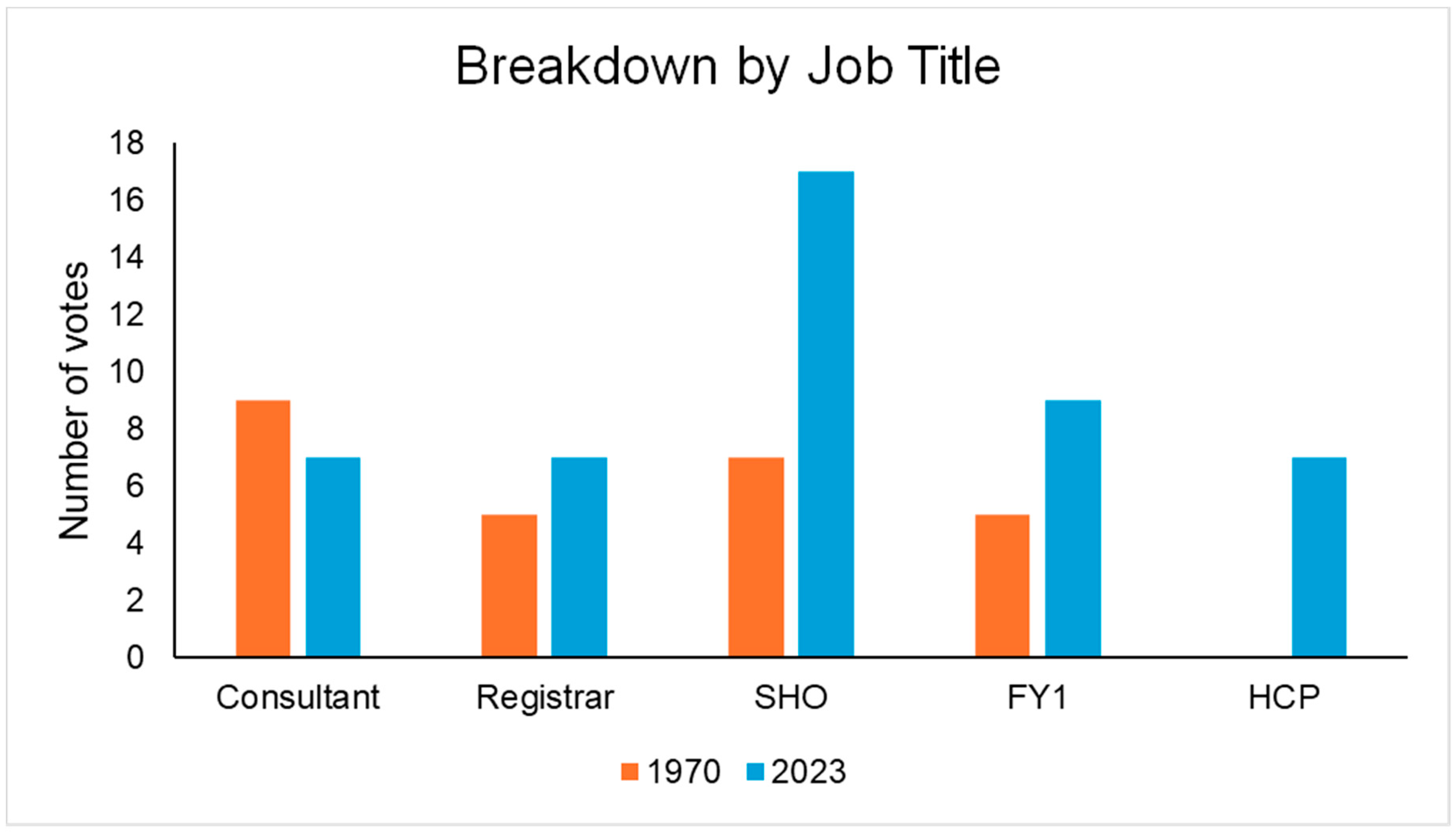

In answer to the question ‘would you rather be a burns SHO in 1970 or 2023?’, 36% voted for 1970 and 64% for 2023. Nine out of 16 consultants (56%) voted for 1970, whereas 58% of registrars, 71% of SHO’s, 64% of FY1’s and 100% of allied HCP’s voted for 2023 (

Figure 5).

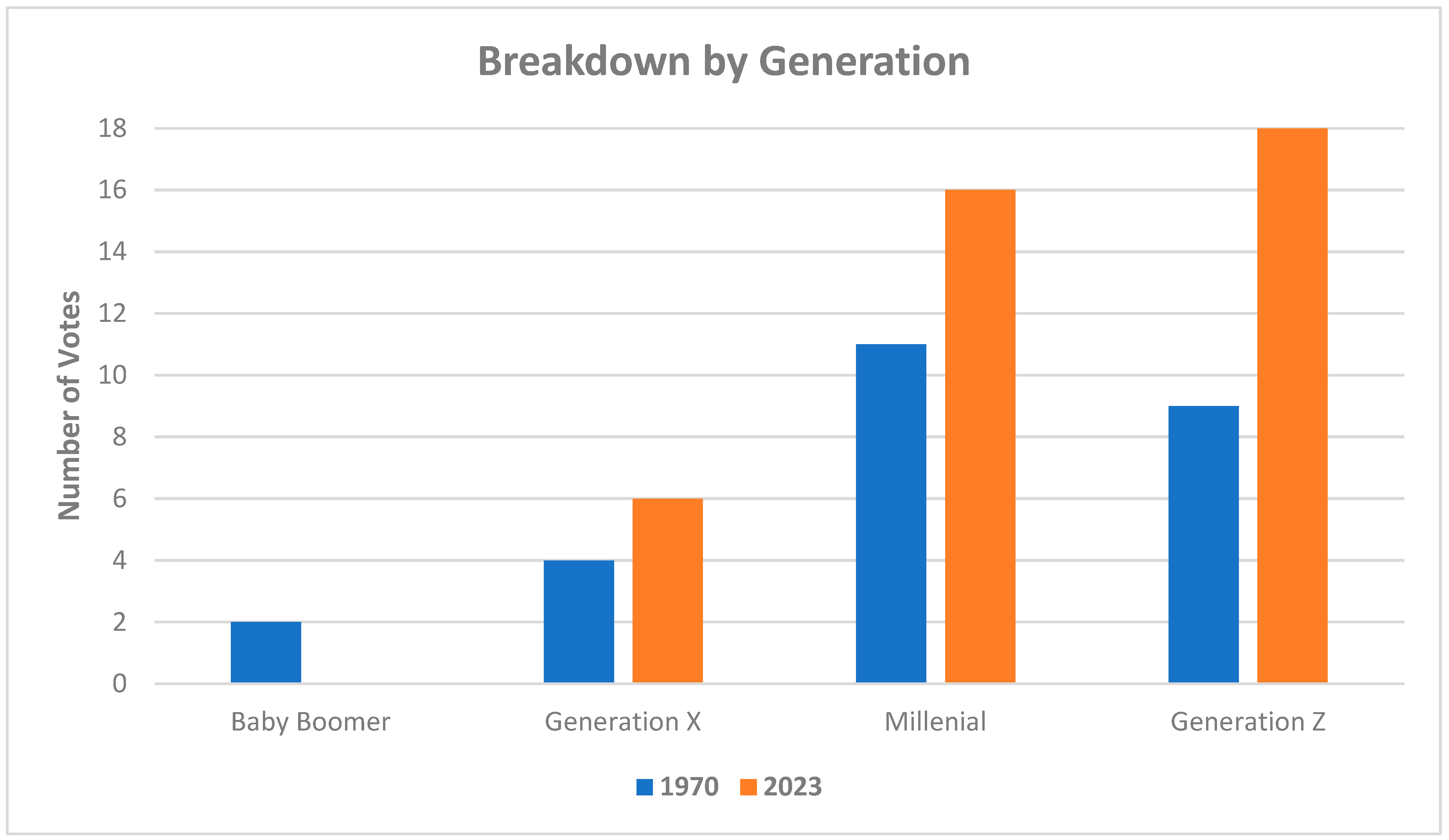

Seven respondents were excluded from statistical analysis due to incomplete demographic information, all of which were allied health care professionals. The mean age of voter for 1970 vs 2023 was 32 and 38 respectively (p= 0.036 unpaired T-test). Broken down by generation this is demonstrated in

Figure 6. Using binary logistic regression, a statistically significant (p= 0.043) relationship between age and preference was demonstrated. Gender (p= 0.165) and prior burns SHO/FY2 experience (p= 0.53) were not found to be statically significant (chi-square test).

Discussion

A higher proportion of total votes for today’s working conditions were observed. This is interesting when viewed with the current background in the United Kingdom of issues with workforce motivation, pay disputes and working conditions. Motivating factors behind this could be due to reduced or ‘safer’ working hours, rest days and more time to enjoy activities outside of work. However, many still voted for 1970, with a skew to corelate with seniority. It has been reported when considering recruitment and retention within business models, there are significant generational differences in values and motivations for choosing and staying with an employer (Benítez-Márquez MD). With a shifting focus to satisfy the priorities of generation Z, employers in 2020 reported a move to better working environment and work-life balance. Although not universal, the differences observed between the generations of doctors working preferences in our study therefore is perhaps unsurprising.

There are some limitations with the survey, the recollections of over half a century ago are those of a single junior doctor, working in a single burns centre. Extrapolations of others’ experiences at the time cannot be made. Similarly, the survey results represent the opinions of workers in the burns centre at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital only.

Summary

Wide ranging differences in the domains of finance, working patterns and clinical care have been described in the same burns unit 50 years apart. When presented with this objective data, the majority of clinicians working in the same department today feel the working conditions at present are preferential. It is noticeable however, that this was not universal, generational differences were demonstrated. We invite you to reflect on your current or past experience working as a junior doctor, and consider when you would rather have worked.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Toby Austin and James Forrest; Writing – original draft, Grant Coleman; Writing – review & editing, Sarah Bache.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hardwicke J, Kohlhardt A, Moiemen N. The Birmingham Burn Centre archive: A photographic history of post-war burn care in the United Kingdom. Burns. 2015. 41(4):680-8. [CrossRef]

- D Jackson, P Stone, angential excision and grafting of burns - The method, and report of 50 consecutive cases, BJPS 1972 and 25, 416-426. [CrossRef]

- Doctors and the European Working Time Directive [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 28]. Available from: https://www.bma.org.uk/pay-and-contracts/working-hours/european-working-time-directive-ewtd/doctors-and-the-european-working-time-directive.

- White C. Was there ever a golden age for junior doctors? BMJ 2016; 354 i3662. [CrossRef]

- Smith F, Goldacre MJ, Lambert TW. Adverse effects on health and wellbeing of working as a doctor: views of the UK medical graduates of 1974 and 1977 surveyed in 2014. J R Soc Med. 2017 110(5):198-207. [CrossRef]

- Freudenberger, H. J. Staff burn-out. J Social Issues 1974 and 30, 159-165. [CrossRef]

- Imo UO. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among doctors in the UK: a systematic literature review of prevalence and associated factors. BJPsych Bull. 2017; 41(4):197-204. [CrossRef]

- House of Commons Archive - Doctors and dentists pay. HC Deb 21 July 1970 vol 804 cc419-40.

- Janzekovic Z. A new concept in the early excision and immediate grafting of burns. J Trauma. and 1970, 10(12):1103-8. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G., Lloyd, M., Parker, M., Martin, R., Philp, B., Shelley, O., & Dziewulski, P. The Baux score is dead. Long live the Baux score. J Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2012 and 72(1), 251-256. [CrossRef]

- Brusselaers N, Hoste EA, Monstrey S, Colpaert KE, De Waele JJ, Vandewoude KH, Blot SI, Outcome and changes over time in survival following severe burns from 1985 to 2004. Intensive Care Med. 2005 and 31(12):1648–1653. [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Márquez MD, Sánchez-Teba EM, Bermúdez-González G, Núñez-Rydman ES, Generation Z Within the Workforce and in the Workplace: A Bibliometric Analysis, Front. Psychol. 2022, 12-2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).