3.2. Caregivers’ Goals for Their Children

When asked what their goals are for their children, participants most often identified health-related goals (mentioned 34 times by 18 focus group participants and once by one survey respondent). These goals included their child being able to care for themselves in the future (i.e., their child having more autonomy in their care, being able to advocate for themselves, being able to access and utilize resources to help them with their condition, reduction in medications needed, not having to deal with insurance issues) and their children not being hindered by their diagnosis, including their condition being eradicated or cured, living a long life, and meeting developmental goals.

Several non-health related goals (mentioned 22 times by 16 focus group participants) were also expressed by caregivers, including goals specific to persons living with a condition such as the child being able to define themselves outside of their disease, being able to educate others on their disease, and communicating using a tablet. In addition, caregivers communicated goals for their children not tied to living with a genetic condition, such as doing typical kid things (i.e., learning to drive, making friends, participating in sports, attending sleepovers), feeling included in life, having good relationships with people outside the immediate family, being a nice person, living a normal life, and becoming more independent.

“I think advocating for themselves, taking care of their bodies, preventing as much illness as they can, listening to their bodies as well. And we teach our boys you are not your disease. The disease is something that you live with. And so, my hope for them is just for them to live full long, happy lives. My son is in competitive sports, and I would hope that he is able to continue to do that as long as it finds him happiness. And I don't want his physical ailments to prevent him from doing the things that he wants to do with his life.” – Focus group participant

“And I love now she's five and a lot of the times the doctors or nurses will still ask me questions or still have the conversation with me and I'm like, ‘She is here now. She can talk now. She can kind of understand.’ So, I like them to talk to her and ask her questions and I want her to feel comfortable in advocating for herself and communicating. And if something doesn't feel right or she disagrees with a doctor, she disagrees with a nurse, I want her to be able to stick up for herself, advocate for herself, it's her body, it's her life. The doctors know a lot about the condition, but they're not living it. So, I just want her to have confidence in speaking to the doctors.” – Focus group participant

3.3. Key Factors That Comprise or Influence Long-Term Follow-Up Care

In discussing what comprises quality LTFU care and the factors that impact LTFU access and engagement, family caregivers identified factors that can be summarized into three themes: communication and relationships with providers; care team roles and factors; and care access and utilization factors. Communication and relationships with providers as well as care team roles and factors were the most prominent themes among focus group participants, both mentioned at least once by each participant (113 and 100 mentions by focus group participants, respectively). The theme of care access and utilization factors was only slightly less prominent, discussed by 22 out of the 24 focus group participants (85 total mentions). The most prominent theme among survey respondents was care access and utilization factors, mentioned by 16 out of the 33 respondents, followed by care team roles and factors (mentioned by 12 respondents), and communication and relationships with providers (mentioned by 1 survey respondent).

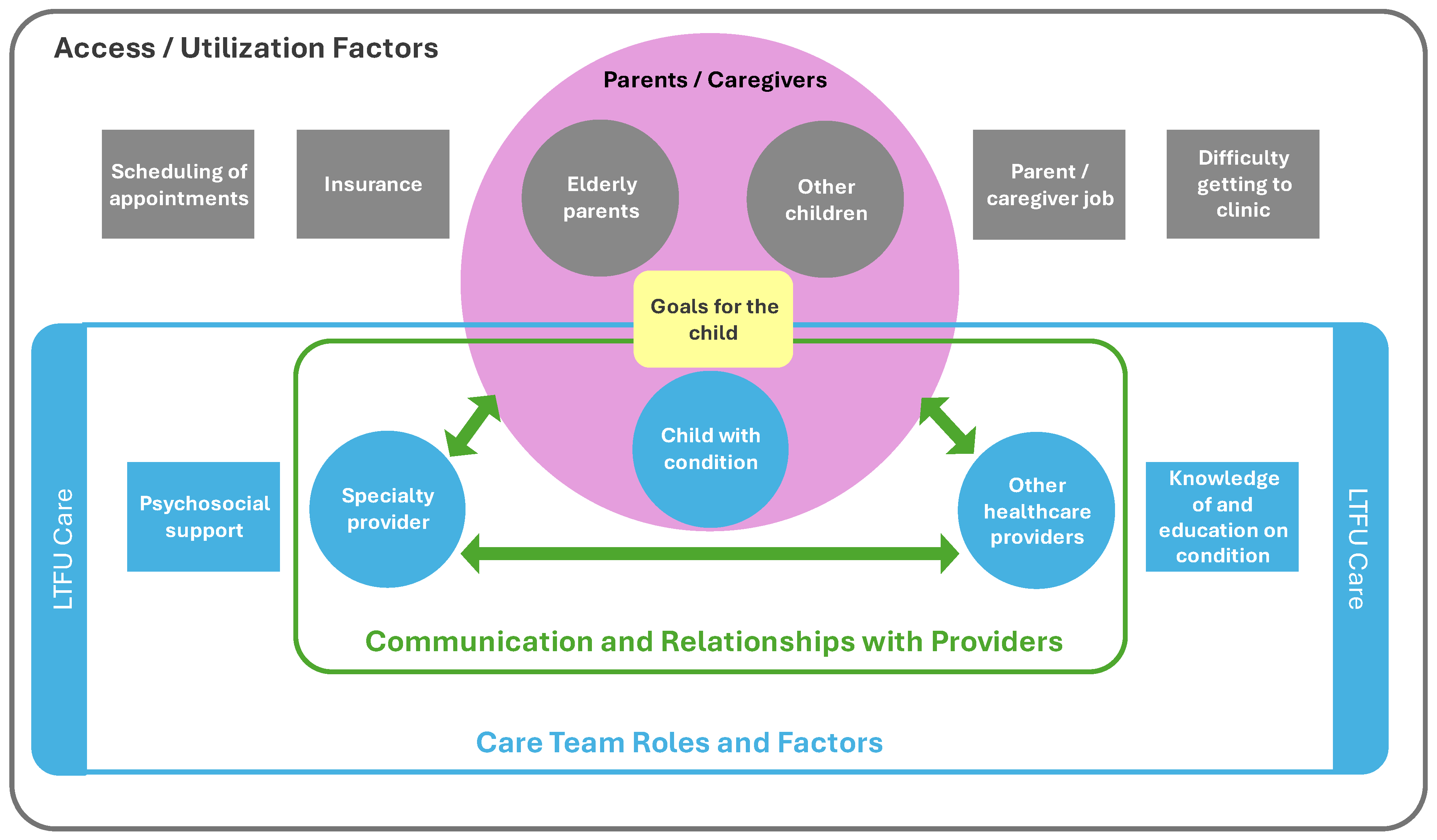

Based on the input from caregivers in this study, a model was developed to depict the interplay of the themes identified in accessing and engaging with LTFU care from the caregiver’s perspective (

Figure 1). In the model, the caregivers play a vital role, with their family at the core of LTFU. Within the family unit are the parents’/caregivers’ goals for their children which may guide the family and the rest of the care team in caring for the child as a whole person who is not defined solely by their disease. The family and provider relationship, which is built through communication, is also at the core of the model. Communication and relationships between the family and providers, along with supportive factors of psychosocial support for the family and knowledge and education, comprise LTFU care in the model. LTFU care operates inside an environment that is impacted by access and utilization facilitators and barriers (i.e., scheduling, insurance, elderly parents, other children, work, and transportation to the clinic).

3.3.1. Communication and Relationships with Providers

Communication with Providers

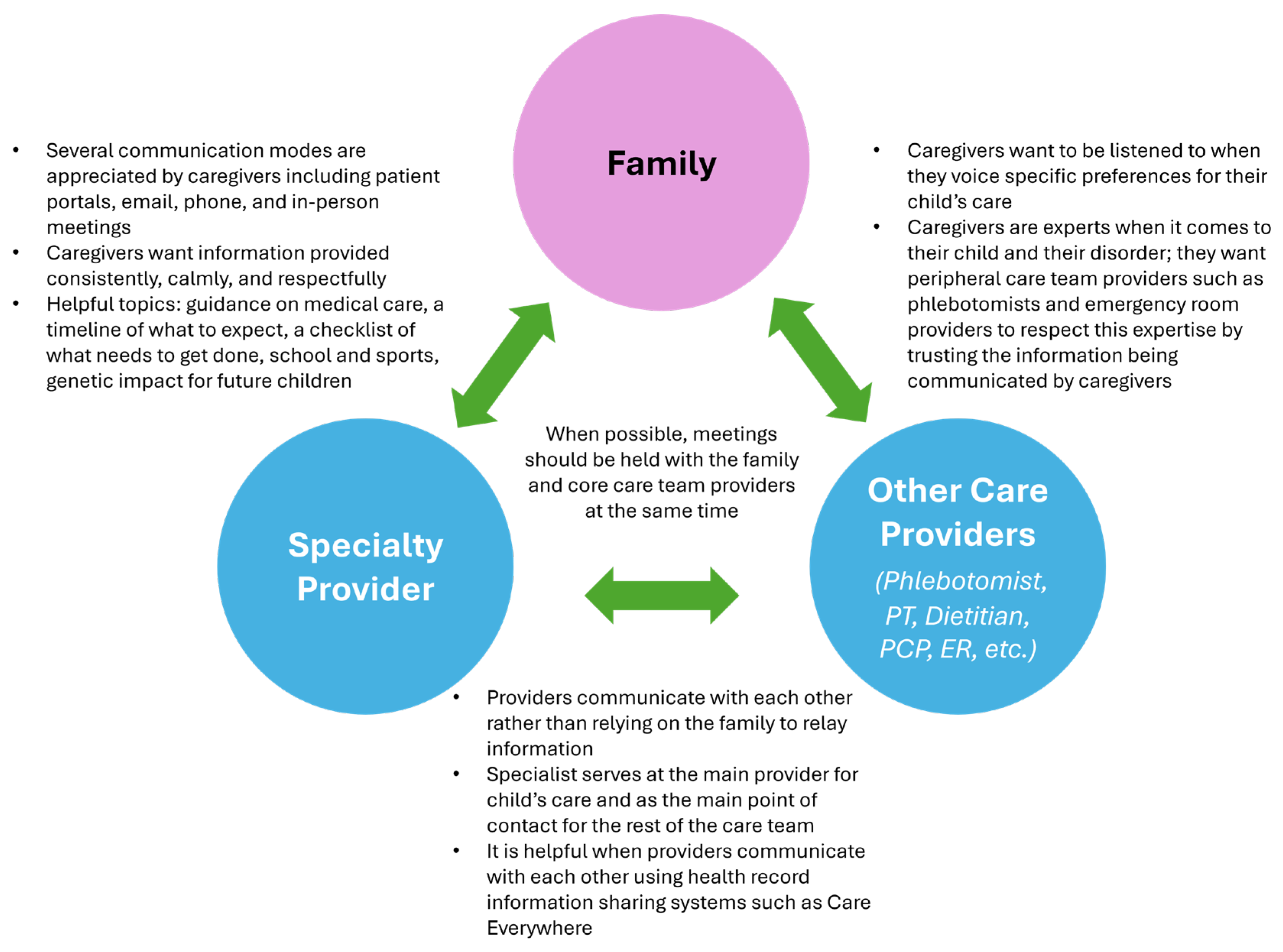

All focus group participants and one survey respondent identified communication as a key component to LTFU which is why it is central to the model. Caregivers collectively highlighted a triad of communication as an essential piece of LTFU care. The triad consists of communication between the family and the specialty provider, the specialty provider and other care providers (e.g., primary care, emergency care, hospitalists, etc.), and the family and other care providers. According to caregivers, communication needs to be bi-directional, flexible, respectful, timely, and must take place between each of the nodes in the triad.

Caregivers discussed the importance of being able to reach out to the specialty clinic with questions or concerns, whether via a patient portal, email, phone, or in-person, and the specialty clinic communicating with the family, including responding quickly to questions, going over a timeline of what to expect and what will need to be done next, and asking the family for feedback. In addition, caregivers expressed a desire for providers on the child’s care team to communicate with each other about the child’s care and for other providers (i.e., non-specialty providers) to communicate with families in a way that respects their expertise with their child’s condition and intimate knowledge of their child’s health. This communication triad can be seen in the context of the broader LTFU model in

Figure 1 and in more detail in

Figure 2, which includes the specific factors that contribute to its success, as noted by caregivers.

“Quality care for me has been the response time to questions, because we have to feed them every day and sometimes, especially in the beginning, in your first year of PKU, the worry that goes along with what, if what you're doing is going to be damaging, I would say quick response time is really important.” - Focus group participant

“And before I leave [the appointment], they go over when's their next appointment. They also go over their school plan and things like that. So as the kids have gotten older … it's new things to consider. So, daycare versus school, now it's sports, but I think it's the scheduling the appointments and scheduling them in advance and then knowing how frequently we need to go in. And each appointment may be blood work at this appointment, another appointment may be a doppler, so I know when to expect those every couple months or per year.” - Focus group participant

Caregivers identified communication breakdowns in the triad as barriers to LTFU. These breakdowns included caregivers not feeling listened to by those performing medical procedures, families not having a way to communicate with a provider directly, providers not communicating with others on the care team, and inconsistencies in the specialty clinic’s communication with the family.

“One time we went to the emergency room, [child] was really sick, and I told the nurse this arm is really the best one to do [the blood draw]. [Nurse] didn't listen to me, and she did it on the right and the arm was really swollen … Now, [child] gets really anxious about just going to the hospital because of drawing her blood.” - Focus group participant

“The three different groups [family, specialist, and pharmacy] - your triangle has to be working well and sometimes it doesn't all fire on the same cylinders at the same time.” - Focus group participant

Relationship Between the Family and Providers

Focus group participants identified the relationship between the family and their children’s providers as a key factor in the quality of LTFU care. When describing good relationships with their providers, caregivers used the terms “respectful” and “compassionate” and noted an appreciation for providers taking the time to get to know their child and the family. Positive family-provider relationships contributed to family empowerment in LTFU decision making, giving caregivers the confidence to push back on providers when they felt it was necessary.

“I feel like our doctor is really cool. I have a good rapport with her. And they like to say, ‘Oh, if your child's had a cough for five days, let us know, we'll put them on antibiotics.’ I'm like, ‘No, I'm not doing that.’ ... So, I kind of feel it out. I bring home my stethoscope; I listen to her lungs. And I stay in touch with them. And [doctor] is very respectful of the decisions I make.” - Focus group participant

Conversely, caregivers who experienced poor relationships with their providers didn’t feel heard, didn’t feel their family choices or values were supported, or felt judged by their providers.

“I felt it two different ways and the pressures in both ways about what you're doing and the lack of understanding from [the providers] is still there. And I wish that that would change and give more support for whatever choice a family makes one way or the other. And I felt no matter what, there was judgment and with a child that has additional medical needs, that pressure is even greater and even harder, and you feel even more alone in trying to make the right decisions for your child.” - Focus group participant

3.3.2. Care Team Roles and Factors

Caregiver’s Role and Needs

Focus group participants expressed that they play a central role in accessing and maintaining LTFU for their child. Some of the tasks associated with this role include advocating for their child, staying on top of appointments, communicating with the care team including challenging the doctor when needed and seeking input from other providers, building relationships with their child’s providers, and educating non-specialty providers on their child’s condition and needs.

“I'll just ask to get a blood draw done, even if [provider] tells me, ‘No, that's not a symptom.’ And there was one time that [provider] was off, and [child] did need a dosage change, but other than that I try to listen. I try not to be that overbearing parent, but I am also the voice for my daughter. So, I'm like, ‘No, let's just go get [child] checked.’" - Focus group participant

Lack of knowledge among non-specialty providers was cited by focus group and survey participants as something that makes it difficult to get the care they need for their child. In these circumstances, parents and caregivers stated that they would have to advocate for their child by educating providers on their child’s condition.

“The only times where we've had disagreements have been with our pediatrician and nurses and things like that. And it has gotten I wouldn't say combative, but definitely from both sides where we're voicing our opinions and the pediatrician or the nurses in the hospital think that they know what they're doing and then we call them out, ‘Actually, that's not the cutoff for those labs,’ or things like that. It goes back and forth and then they'll bring in the doctor or they'll bring in the residents and then they'll try to say the same thing. And we're like, ‘No, that's not the cutoff.’” - Focus group participant

“They [non-specialty providers] have no idea what it is, so it's like you have to explain it to them.” - Focus group participant

While the need for educating non-specialty providers was often discussed in the context of hospital or primary care, caregivers were also confronted with lack of knowledge when calling to schedule their child’s appointments. Schedulers who did not understand the nuances of LTFU protocols and did not know how to contact specific schedulers responsible for handling LTFU appointments would give parents an extremely inaccurate estimate of when their child could be seen.

“We're hitting this barrier where I had called and the scheduler just had no clue and she didn't have access to the right schedule so she's telling me that the doctor doesn't have an appointment for a year and a half and I'm like, that's ridiculous.” - Focus group participant

Caregiver burnout, denial, fear, feeling overwhelmed, or previous negative medical experiences were identified by caregivers as barriers to staying engaged in LTFU care.

“And when you find out that your kid has a genetic condition, it's overwhelming and then you don't feel like … the doctors … support your family values. And at some point, I think some parents just give up because it is so much to manage mentally, especially if you have more than one kid or even if you just have one kid that you'll have seventeen specialists in addition to the normal doctors. It is just so overwhelming that you just withdraw … because you have no other option.” - Focus group participant

Caregivers noted that connection to other families living with a similar condition (e.g., support groups) and psychosocial supports such access to a social worker and psychological support for the child and the family were supportive factors for families accessing and maintaining LTFU.

“It is very isolating. But what was great was that I got connected really early on to a Facebook page that was just directly for children with my son's disease … And then also in the area, the specialist had given me names to people that were close enough that had the same disorder as my son. So, I thought that was really helpful and comforting too to just know that there are people that have the same issues or feeding issues.” - Focus group participant

“Or at least even to have a support group with people even that have children with the same condition, that would be helpful, too. Maybe just so that I’m not bothering the doctor every single chance I get to, ‘Hey, this is just a developmental thing,’ or, ‘Hey, this is an actual what she’s got type of thing?’” - Focus group participant

“…the emotional impact of that transition into rare disease life or special medical care, I think that’s something too, that getting people the support that they need to be able to effectively care for their children. It’s more than just the technical knowledge. I think it’s making sure that they’re in a good place to be able to do that.” - Focus group participant

Caregivers also reported finding comfort in being educated on the disease and what to expect at each stage. In addition, caregivers discussed how their knowledge of the disorder allowed them to better advocate for their child and to openly disagree with providers, especially in circumstances where caregivers sensed a provider’s lack of knowledge.

“To me, it's giving the parents the tools that they need, the knowledge and tools that they need to be able to manage that independently.” - Focus group participant

“I've disagreed with hospital staff, not specialists. And I think probably with all of us, we're taught to really advocate for our children in places where their specialists aren't there, and nursing staff in particular who are in the room more. And I've had to really advocate, I'm on it in a hospital situation especially a lot of times we're not in a children's hospital, we are up in a non-children's facility and so I certainly just rely on my knowledge and the disorder as I know it.” - Focus group participant

Team of Providers Treats the Whole Child

According to focus group and survey participants, LTFU care, although led by a specialist, should be delivered by a team of providers, medical and non-medical, who treat the whole child. A wide range of providers including specialists, primary care providers, dieticians, physical therapists, pharmacists, condition specific foundations, mental health professionals, social workers, and genetic counselors were highlighted by caregivers as being part of their child’s care team and contributing to their LTFU.

“[Our care would be improved] If our child was looked at as a whole person, rather than separate symptoms.” - Survey respondent

“So, they connected us with the CF Foundation quickly and made inroads there. Medications are extremely expensive for people with CF, so insurance support, pharmacy support, and then just the psychology, the emotional support.” - Focus group participant

“It is a whole team of people that we see on the regular that we can request to see more often. Actually, they're pretty cool because they do treat the whole person. And it's like right now I'm like, we don't need a psychologist so much because she's a little kid. But man, I understand why that's such an important part of the team. As she gets older and feels isolated with her disease as a teen or something, that's a thing. And so, they have so many people in place to manage every aspect of the disease, emotional, physical. That's huge.” - Focus group participant

With a large team of providers, however, there are more opportunities for turnover in care team members which can lead to gaps in families getting the care they need.

“And we had an amazing mid-level that we worked with, and [provider] was just on point, she was on top of the research and when we would reach out to her, she could fix things, she could answer questions, and then she left … And we've had a lot of struggles since that has happened, a lot of struggles trying to get [child’s] prescriptions refilled.” - Focus group participant

A role often missing from their child’s care team, as noted by focus group and survey participants, is that of a care coordinator. Caregivers expressed the desire for a care coordinator to help manage their child’s care across the team of providers and the high volume of appointments. Without care coordinators, caregivers assume this role which can be time consuming, overwhelming, and detrimental to their other commitments such as work and caring for other family members.

“So to have some of that, ‘Hey, here's things to be checking,’ even if it's just a checklist to say, ‘Get the labs done, get this scan done, get the test done, get the evaluation scheduled,’ to have that, even if it's not a worry, you've at least done the example and to have that confidence that somebody … is reviewing your kid's medical record from a global top-down perspective.” - Focus group participant

3.3.3. Care Access and Utilization Factors

Participants identified a few key factors that influence whether a family can access or utilize the LTFU care that is available. These include insurance and logistical factors that impact caregivers' ability to schedule and/or attend LTFU care appointments.

Insurance

Insurance was identified by focus group and survey participants as a barrier to LTFU or as something that could be improved in their LTFU experience. Caregivers discussed how lack of insurance, poor insurance coverage, complex enrollment processes, and difficulties getting treatment authorization make it difficult for families to get the care they need.

“Every year the reauthorization process for her medication is exhausting and cumbersome. There is lots of room for process improvement - on the insurance side of this.” - Survey respondent

“… my kiddos, also, they take the same medications every single month that they've been taking since they were born and at the pharmacy every single month there's an issue with the insurance. And we have private insurance, and they always have to call it in, and it always takes days for them to get it figured out.” - Focus group participant

Once they completed the complex enrollment process, public insurance programs, such as Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and TriCare were considered very beneficial to families’ LTFU care.

“The CHIP program we went through when she was little, getting evaluated … I didn't understand everything I was doing. I felt like I had to go through a lot of hoops … but it's part of their program, and it's kind of putting out a safety net, I feel like. When they get someone into certain programs, they really do investigate all the needs and try to support the families in that way. And I mean, I think that's pretty spectacular.” - Focus group participant

“Being established with Medicaid has been pretty sweet.” - Focus group participant

Given the complexities of enrolling in public insurance or obtaining authorization for critical procedures and medications, caregivers see value in having access to insurance specialists who can help families navigate insurance issues.

“… to have maybe an insurance specialist or something that could navigate all the different insurances and help families get on Medicaid and help navigate Medicaid and if there's other funding sources out there. Because, again [with] PKU … it's just an expensive disorder and [the] clinic, while they try and offer suggestions, I think they're so busy dealing with just the medical aspect of it. It might be nice to just have somebody that can help with the insurance and financial.” - Focus group participant

Logistical Factors

Caregivers in both groups also identified logistical factors that are barriers to accessing and maintaining LTFU. The most frequently mentioned logistical issue was difficulty getting to their child’s medical visits because of geographic distance, weather, issues with transportation, or no internet access for telemedicine visits. The family’s obligations to things outside their LTFU world such as caring for other children or elderly parents, caregivers’ jobs, and their children attending school were also barriers.

“Yeah, it's really hard. Actually, my husband lost his job because … of the whole hospital stay … My son has the medical condition, has siblings, so [caregivers] have to share the duties.” - Focus group participant

“I spent hours upon hours upon hours waiting in waiting rooms and I was also a full-time working parent and so it became almost impossible. I had to quit my job because of the amount of needed appointments for two different issues that were going on along with the care that was needed.” - Focus group participant

Scheduling difficulties pose another layer of logistical complexity. Caregivers discussed several issues with scheduling including not being able to get in touch with the right scheduler, not being able to bulk schedule appointments on the same day, difficulties rescheduling appointments, and long wait times for appointments.

Caregivers expressed a desire for more flexibility with frequency and format (i.e., virtual, in-person) of clinic visits to offset the difficulties posed by the logistical factors mentioned above.

“… I think spreading out those appointments would be helpful and just going to the lab, but then just doing a virtual visit for the results.” - Focus group participant

“I mean, you can't see PKU. It's in their blood, it's in their body, so he doesn't really need to be physically seen. So, the telehealth is nice, because it cuts down on drive time.” - Focus group participant