Introduction

Perceived overqualification (POQ) has become an unavoidable phenomenon in society, particularly in China, where it is more prominent. Overqualification refers to the overuse of education and the underutilization of skills. Specifically, it describes a situation in which an individual’s education, work experience, skills, or abilities exceed the requirements of their job.[

1,

2] To some extent, it reflects underemployment, either on the part of the employees or the organization.[

2,

3,

4] Currently, perceived overqualification exists across various organizations and institutions, and the situation is particularly severe in China. If this "person-job mismatch" is not addressed in time, it may create a vicious cycle, incurring significant management costs for organizations. In recent years, this issue has gradually become a hot topic for scholars.

Many scholars believe that overqualification can lead to a series of negative effects, such as decreased job satisfaction,[

5] increased turnover intentions,[

2] and counterproductive work behaviors.[

6] However, recent studies have shown that the behavior of overqualified employees is not uniform and can be influenced by external factors such as individual goals, organizational environment, and social context.[

7,

8] Depending on how they perceive the situation, overqualified employees may also exhibit positive behaviors. For instance, if employees understand that overqualification is a common occurrence in the competitive job market, the negative impact of overqualification may be mitigated.[

7]

Overqualified employees typically possess stronger work skills and higher efficiency, allowing them to complete tasks more effectively. This makes them more likely to exhibit behaviors that benefit their work. [

3]Empirical research shows that overqualified employees often have clearer goal orientations, and in addition to fulfilling in-role duties, they tend to demonstrate extra-role behaviors, such as constructive deviant behavior (CDB).[

9] Constructive deviant behavior is defined as “voluntary behavior that violates significant norms with the aim of improving the welfare of the organization, its members, or both”.[

10] These behaviors can lead to positive outcomes in organizational innovation, interpersonal interactions, and the overall development of the organization.[

10]

Currently, research on the mechanisms and effects of overqualification and constructive deviant behavior is still insufficient, particularly with regard to the role of organizational leadership. According to the Cognitive-Affective Personality System (CAPS) theory, the external environment and experiences individuals encounter influence their internal cognitive and emotional units, which in turn affect their responses and behaviors toward the external environment.[

11] In today’s digital economy, the disruptive influence of digital technology has impacted various fields, including corporate leadership behavior. Digital leadership, as a product of this new era, emphasizes five key capabilities in leaders: creativity, reflection and inquiry, curiosity, broad knowledge, global vision, and collaboration.[

12] The core capabilities of digital leadership not only influence the behavior of leaders but also affect employees' cognition and emotions, thereby moderating their behavioral responses. For overqualified employees, the creativity and inquiry spirit emphasized by digital leadership can offer more challenging tasks and development opportunities, fulfilling their need for achievement and self-worth, thus encouraging positive constructive deviant behavior. However, research on the relationship between these factors remains scarce.

Furthermore, in the 21st-century labor market, employees born in the 1990s exhibit distinct personality traits, such as strong individuality, assertiveness, and reduced tolerance, making them less likely to conform easily. When faced with "underutilization," they are more inclined to express dissatisfaction, make suggestions, or exhibit either destructive behaviors that harm the organization or constructive deviant behaviors that contribute to its development. Based on this, the aim of this paper is to explore how overqualification affects employees' constructive deviant behavior, analyze the mechanisms and boundaries of this relationship, and examine the moderating role of digital leadership as well as the generational differences that influence these boundaries. The structure of this paper is as follows: the second part outlines the theoretical foundation and research hypotheses, the third part describes the research design, the fourth part focuses on empirical analysis, and the fifth part concludes with discussions.

Hypotheses Development

The proactive motivation model proposed by Parker and other scholars suggests that employees’ proactive behavior are driven by three motivational aspects: “Can do”, “Reason to” and “Energized to”.[

13] aspect addresses the question, "Am I able to do this?"—reflecting employees' internal confidence and capabilities in taking action. "Reason to" pertains to why individuals choose to engage in certain behaviors (e.g., "Do I want to do this? Why should I act?"). "Energized to" represents the emotional drive that fuels goal generation and effort towards achieving proactive goals. Although CDB violates organizational norms, it is still a voluntary behavior.[

14] In terms of behavioral connotation, CDB involves employees' deviant actions that stem from positive motivation, with the intent to take responsibility for the organization and improve its well-being.[

13] At its core, CDB is an initiative-driven behavior. Therefore, the proactive motivation model can help explain the logical relationships among the study’s variables.

POQ and CDB

From the “Can do” perspective, POQ reflects employees' subjective belief that their qualifications, education, experience, and skills surpass the requirements of their current role. This perception is closely tied to their judgment of personal competence. First, employees who perceive themselves as overqualified believe they not only excel in their current tasks but also have the potential to innovate, challenge norms, and engage in proactive behaviors beyond their regular duties.[

13] This confidence in their abilities fosters a desire to go beyond routine tasks and contribute meaningfully to their work environment. Moreover, these employees often complete their tasks more efficiently, leaving them with additional time for reflection and creative thinking. This extra time encourages divergent thinking, novel associations, and analogical reasoning, all of which increase the likelihood of challenging the status quo and driving innovation.[

14] Finally, from the perspective of self-verification theory, overqualified employees tend to seek out more complex and challenging tasks, driven by the need for peer recognition and validation of their skills. This drive not only satisfies their need for acknowledgment but also aligns their perceived competencies with opportunities for application, thus enhancing job satisfaction and solidifying their organizational role [

15].These proactive behaviors extend beyond regular responsibilities and are often categorized as Creative Deviant Behaviors (CDB), which are crucial for fostering a dynamic and innovative workplace.

In the context of “Energized to” individuals often evaluate their situation by comparing their effects, outcomes, and current state with the potential state they believe they deserve. When there is a noticeable between the outcomes received and those expected, feelings of deprivation may arise. This sense of deprivation deepens as the disparity grows, leading to dissatisfaction, frustration, or even anger, as posited by Crosby. Relative deprivation theory posits that individuals who perceive themselves as overqualified are more likely to experience heightened feelings of deprivation and negative emotions. This emotional response initiates a feedback loop, intensifying these feelings and and generating motivational energy. As a result, individuals are more inclined to engage in proactive behaviors to address their perceived discrepancies.[

15] This deprivation-driven energy not only propels individuals towards action but also highlights the importance of addressing the root causes of POQ in organizations. By recognizing and effectively managing these disparities, organizations can channel this energy to drive positive change and cultivate a more satisfying work environment. Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: the POQ positively promotes CDB.

The Moderator Effect of Digital Leadership

Navigating the complexities of workplace risk evaluation requires an intricate process involving both employee motivation and behavior. As Parker, Bindl, and Strauss (2010) highlight, constructive deviant behaviors (CDB) possess a dual nature, combining legitimate intent with potentially unauthorized actions.[

16] Employees engaging in such behaviors may violate organizational norms and challenge leadership authority, risking criticism or punishment from superiors. From the perspective of the conservation of resources theory, employees, as rational actors, carefully weigh the risks and benefits of engaging in CDB. They are more likely to engage in such behaviors only when the perceived benefits outweigh the potential losses.[

17]

However, to fully embrace CDB, employees require more than just ability and motivation. They need leadership support to mitigate risks. According to proactive motivation model, leadership plays a pivotal role in stimulating employees' proactive behaviors, encouraging them to engage in CDB by reducing the perceived risks involved.[

16] Furthermore, leadership style is a key situational factor that significantly influences employees’ likelihood of engaging in CDB.[

18]

Digital leadership, as a modern leadership approach, aligns with the needs of the digital economy by prioritizing the integration of technology and innovation to drive business growth. First, through the use of advanced digital tools, data analytics, and technological innovations, digital leaders can more accurately assess employees' skills and potential. This enables them to assign more challenging tasks and projects to overqualified employees, which helps to mitigate the negative emotions associated with feeling overqualified. In turn, this sense of alignment motivates employees to engage in constructive deviant behaviors, such as proactively suggesting improvements, to address work challenges.Second, digital leadership places a strong emphasis on autonomy and flexibility. Overqualified employees typically desire greater autonomy in their roles. By leveraging digital platforms and tools, digital leaders can create a more flexible work environment, allowing employees to have more control over how they complete tasks. This autonomy satisfies the self-efficacy needs of overqualified employees, encouraging them to channel their energy into positive, constructive deviant behaviors rather than negative or counterproductive actions. Finally, digital leaders can provide access to cutting-edge digital technologies, tools, and learning opportunities that help overqualified employees broaden their skill sets and expand their knowledge. By demonstrating the practical value of their expertise, employees are less likely to experience frustration related to overqualification. This, in turn, encourages them to become more actively involved in organizational improvement and innovation initiatives.

Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Digital leadership strengthens the positive relationship between POQ and CDB.

Intergenerational Differences in the Relationship between POQ and CDB

Parker (2010) proposed personal values are important contextual factors influencing employees’ engagement in proactive behaviors through the model of proactive motivation.[

16] Similarly, Liu suggested that individuals’ work behaviors are shaped by their work values, which externalize sa positive or negative factors based on cognitive structures, leading to corresponding attitudes towards work.[

19,

20] However, due to different life experiences, environments, and backgrounds, employees from different generations develop distinct work values. Older employees often prioritize values such as responsibility, morality, and tradition, and material achievements, with a focus on status, independence, and power acquisition.[

21] In contrast, younger generations are more focused on work-life balance and personal fulfillment, valuing ease and enjoyment at work,[

20,

21] These value differences lead to varying expectations and priorities regarding the organization, resulting in different risk-benefit assessments of work behaviors. As discussed earlier, engaging in constructive deviant behavior (CDB) involves a comprehensive risk assessment process.[

16] Intergenerational differences in work values influence how different generations assess the risks associated with CDB. For instance, older employees may overestimate risks, while younger employees may underestimate them. This results in differing levels of energy motivation and varying forms of CDB across generations.

On the other hand, POQ is a subjective judgment, and different generations may exhibit varying levels of self-awareness. Employees born in the 1990s, for example, have generally spent over a decade in the workforce, gaining substantial experience and job skills. With better access to educational and skills-training opportunities, this generation may have a heightened perception of overqualification compared to earlier generations.

In summary, two main points arise: first, older employees tend to overestimate the risks associated with CDB; second, generational differences exist in the perception of overqualification. Based on this analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: There are generational differences in the effect of POQ on CDB

Intergenerational Differences in the Moderator Effect of DL

Behavioral Decision Theory suggests that human rationality lies between complete rationality and complete irrationality, and is easily influenced by perceptual biases when identifying problems and making decisions.[

22] Employees’ evaluation of overqualification, digital leadership, and constructive deviant behavior, and the subsequent decision-making, is itself a game process. As previously explained, during this process, individuals assess risk and reward and make decisions. If the benefits and losses are balanced, people tend to accept this relationship. Employees born in the 1990s, due to their higher acceptance of technology, emphasis on autonomy and innovation, stronger risk-taking spirit, and faster learning and adaptation abilities, are more likely to exhibit constructive deviant behavior under the support of digital leadership. By offering autonomy, technical support, and a flexible work environment, digital leadership can effectively stimulate the creativity of employees born in the 1990s, reduce dissatisfaction from overqualification, and motivate them to actively drive organizational improvements. In contrast, employees born in the 1970s and 1980s value stability and security more, have lower adaptability to new technology, and are less inclined to take risks, so the influence of digital leadership on their constructive deviant behavior is weaker. They may need more time and support to display similar positive behaviors in a digital environment. Based on the above analysis, we form the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: TThe moderating effect of digital leadership on the relationship between overqualification and constructive deviant behavior shows significant generational differences.

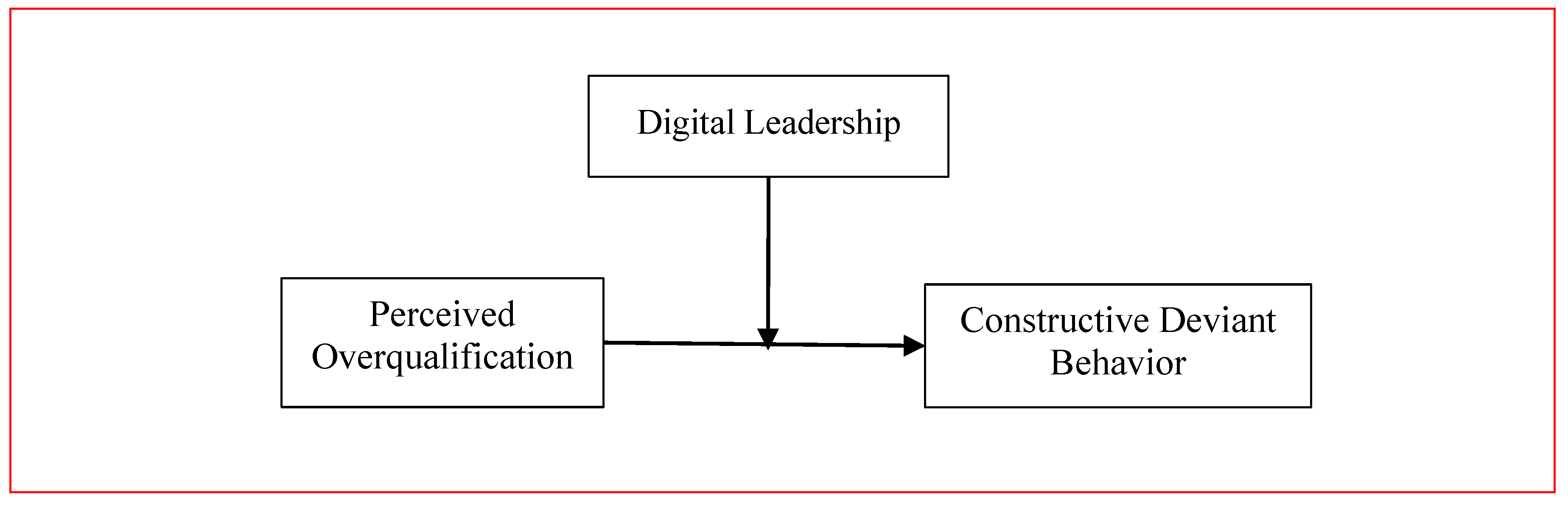

The research model of this study was shown in

Figure 1.

Methodology

Sample and Procedure

This study adopts the intergenerational boundaries division proposed by Meng,[

20] dividing employees into three groups: "Post-90s" (born after 1990), "Post-80s" ( born between 1980 and 1990), and "Post-70s" (born between 1970 and 1980). The survey was conducted in twe waves, in July and September 2022, with 750 questionnaires distributed. After eliminating invalid questionnaires, 596 valid responses were obtained, resulting in a response rate of 79.47%. Of the respondents, 29.70% were Post-70s ((177 employees), 36.41% were Post-80s (217 employees), and 33.89% were Post-90s (202 employees). In terms of gender, 43.96% were male (262 employees) and 56.04% were female (334 employees). Regarding education levels, 27.68% of respondents had a college degree or below (165 employees), 60.57% held a bachelor’s degree (361 employees), and 11.74% had a master’s degree or above (70 employees).

Measurement

The variables in this study were measured using well-established and authoritative scales. To minimize the potential influence of translation and cultural differences, we invited five professors and doctoral students specializing in enterprise management to review, modify, and refine the questionnaire. All items were assessed using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Perceived overqualification (α = 0.908)

POQ was measured using the nine-item Scale developed by Maynard.[

2] The scale measures POQ as a whole and is a unidimensional scale with nine questions. The scale has been widely used in previous studies and has been shown to have high reliability and validity.[

23,

24] A sample item is “I have more abilities than I need in order to do my job”. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.908 and the KMO is 0.930.

Constructive deviant behavior (α = 0.882)

CDB was measured using a scale developed by Galperin,[

25] which is composed of 16 items, including three dimensions: innovation (five items), challenge (six items), and interpersonal (five items). The sample item is “I am happy to find innovative ways to solve problems”. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.882 and the KMO is 0.900.

Ditigal leadership (α = 0.767)

DL was measured using a modified version of the scale developed by Zhu,[

12] which includes five dimensions: creativity, thinking and inquisition, curiosity, and deep knowledge. This scale has been used multiple times in empirical studies. Due to the large number of items, we adjusted the items according to the needs of the study and ultimately developed a scale consisting of 16 items. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.767 and the KMO is 0.844.

Control Variables

In order to more accurately determine the influence relationship between the variables, gender, education, work experience, years of working experience in this company, position, and the number of job-hopping were introduced into the regression analysis as control variables to exclude potential substitution variables and make the results more scientific, and the selection of this control variable was consistent with previous studies.[

20,

24]

Analysis Method

Based on our understanding of intergenerational differences and the content of the study, this paper conducted stepwise regression and group regression analysis using SPSS 24.0. Stepwise regression was primarily used to verify the main and moderating effects of the sense of POQ, CDB, and DL, while group regression focused on examining intergenerational differences.

Results

Homologous Variance Test

To control for potential homologous variance, this study implemented two key strategies. First, respondents were assured of the anonymity of their responses to encourage more accurate and honest data. Second, the order of questionnaire items, particularly those related to key variables, was intentionally randomized to prevent patterned responses. Additionally, the Harman single-factor test was applied to further assess the presence of homologous variance. A comprehensive factor analysis of all measurement items revealed that the first principal component accounted for only 20.992% of the total variance, well below the 50% threshold. This indicates that homologous variance in the data is within acceptable limits.

Reliability and Validity

The method used for reliability and validity testing in this study is widely recognized and has been been validated by numerous scholars.[

23,

24] As described in the previous section on variable measurements, the Cronbach’s alpha indexes for the sense of POQ, DL and CDB were 0.908, 0.882 and 0.767, respectively, indicating good reliability. To assess the validity of the scales, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 23.0. The results showed that the three-factor model demonstrated the best fit (χ²/df = 1.703 < 3, RMSEA = 0.042 < 0.05, IFI = 0.925 > 0.9, CFI = 0.932 > 0.9, TLI = 0.941 > 0.9), All alternative competing models showed poorer fit compared to the hypothesized model proposed in this study.

Correlation Analysis

As shown in

Table 1, the study examines the correlation analysis of variables by dividing the data into three generational groups: "post-70s", "post-80s", and "post-90s". This segmentation helps distinguish cognitive differences in research variables across generations from a descriptive analysis perspective.

Table 1 clearly shows that the value of perceived overqualification (POQ) is highest among "post-70s" employees, lowest among the "post-80s", while the "post-90s" have an average POQ value of 3.423, ranking second after the "post-70s".

The possible reasons for these perceived overqualification differences include the following: first, many "post-70s" employees have substantial work experience, leading them to believe they are highly capable despite lower educational qualifications. Second, "post-90s" employees benefit from an advanced educational environment; however, intense job market competition leaves some feeling underutilized, which increases their sense of overqualification.

Digital leadership (DL) scores are highest among the "post-90s" and lowest among the "post-70s". Similarly, constructive deviant behavior (CDB) is most prominent among the "post-90s" and least observed in the "post-70s". These findings align with intuitive expectations of generational differences. One possible explanation is that the "post-90s", with their higher acceptance of digital technology, self-driven innovation, and a desire for personalized expression, are more likely to unleash creativity and initiative under digital leadership, resulting in increased constructive deviant behavior. The flexible work environment and technological support provided by digital leadership meet the psychological needs of "post-90s" employees for autonomy and achievement, prompting them to challenge existing norms and promote organizational innovation. In contrast, "post-70s" employees, who prioritize stability and security due to their upbringing and career experiences, are less adaptable to digital leadership, show weaker innovation motivation, and tend to have a more conservative work attitude, resulting in fewer instances of constructive deviant behavior.

Further correlation coefficient analysis among the three groups shows a positive correlation between POQ and CDB, and between DL and CDB, with varying strengths. The correlation coefficients, being lower than their respective reliability values, suggest that the relationships between the variables can be further analyzed to explore causal links.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables.

| sample |

Variables |

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

| All sample |

1. Perceived Overqualification |

3.410 |

0.780 |

1 |

|

|

| |

2. Digital Leadership |

3.658 |

0.401 |

0.066 |

1 |

|

| |

3. Constructive Deviant Behavior |

3.452 |

0.613 |

0.426** |

0.207** |

1 |

| 70past |

1. Perceived Overqualification |

3.490 |

0.790 |

1 |

|

|

| |

2. Digital Leadership |

3.604 |

0.406 |

0.100 |

1 |

|

| |

3. Constructive Deviant Behavior |

3.348 |

0.602 |

0.420** |

0.166** |

1 |

| 80past |

1. Perceived Overqualification |

3.314 |

0.798 |

1 |

|

|

| |

2. Digital Leadership |

3.611 |

0.402 |

0.070 |

1 |

|

| |

3. Constructive Deviant Behavior |

3.457 |

0.676 |

0.476** |

0.281** |

1 |

| 90past |

1. Perceived Overqualification |

3.423 |

0.756 |

1 |

|

|

| |

2. Digital Leadership |

3.667 |

0.415 |

0.038 |

1 |

|

| |

3. Constructive Deviant Behavior |

3.499 |

0.563 |

0.402** |

0.209** |

1 |

Hypothetical Test

A multilevel linear regression model was employed to analyze the impact of perceived overqualification (POQ) on employees' constructive deviant behavior (CDB) and the moderating role of digital leadership (DL). Additionally, group regression was conducted to explore generational differences in the effects of these variables, with the results presented in

Table 2. Using the "post-70s" cohort as an example, the regression paths followed these steps: Model 1 included control variables, Model 2 added POQ as the independent variable, Model 3 introduced DL as the moderator, and Model 4 incorporated the interaction term between POQ and DL. The same regression process was applied to the other generational cohorts for consistency in analysis.

Analysis of Main Effect

Using the total sample, a main effects analysis was conducted, with the results presented in

Table 2. In Model 1, control variables such as gender, age, education, work experience, tenure with the current company, position, and job changes were included. The findings revealed that gender and age were significantly negatively correlated with constructive deviant behavior (CDB) (β = -0.167, p < 0.050; β = -0.055, p < 0.1), suggesting that females are more likely to engage in CDB compared to males, and that older individuals are less inclined to exhibit CDB. Education showed a significant positive correlation with CDB (β = 0.234, p < 0.01), indicating that employees with higher education levels are more prone to engaging in CDB. These trends remained consistent across subsequent regression models.

n Model 2, when POQ was added as the independent variable, it demonstrated a significant positive effect on CDB (β = 0.314, p < 0.01). Other control variables remained stable in their influence, and the R2 value increased noticeably, confirming that POQ has a significant impact on CDB, thus supporting hypothesis H1.

Analysis of Moderator Effect

As shown in

Table 2, the results from Models 3 and 4 indicate that DL is positively associated with constructive deviant behavior. The interaction term between POQ and DL yielded a positive and significant coefficient (β= 0.251, p < 0.01), indicating that DL positively moderates the relationship between POQ and CDB. This finding validates hypothesis H2.

Intergenerational Differences

To validate hypothesis H3, the research sample was divided into three groups based on generational cohorts, and regression analyses were performed, as shown in Models 6, 10, and 14 in

Table 2. The results revealed positive correlations between POQ and constructive deviant behavior, with coefficients of 0.260, 0.374, and 0.306 for the post-70s, post-80s, and post-90s cohorts, respectively. All coefficients were statistically significant at the 1% level. Comparatively, the promoting effect of POQ on constructive deviant behavior was strongest among the post-80s cohort and weakest among the post-70s cohort, thereby confirming hypothesis H3.

In the subgroup regression models (Models 8, 12, and 16 in

Table 2), the moderating effect of DL (Digital Leadership) exhibited notable intergenerational differences. Specifically, DL enhanced the positive effect of POQ (Perceived Overqualification) on CDB (Constructive Deviant Behavior) among employees in the post-70s and post-80s cohorts, with interaction term coefficients of 0.453 and 0.319, respectively, both statistically significant at the 5% level. However, DL did not show a significant moderating effect among the post-90s cohort. The primary reason for these differences lies in the varying levels of adaptability, dependency, and trust in digital leadership across generations. Compared to post-90s employees, post-70s and post-80s employees are more dependent on the support provided by digital leadership and have established stronger trust with their leaders in the workplace. This trust makes digital leadership more effective in transforming perceived overqualification into constructive deviant behavior. In contrast, post-90s employees tend to make independent decisions and are less reliant on leadership, resulting in a less significant moderating effect. Based on this analysis, hypothesis H4 is supported.

Table 3.

Results for the main effect and mediating role.

Table 3.

Results for the main effect and mediating role.

| Variable |

Post-80s |

Post-90s |

| M9 |

M10 |

M11 |

M12 |

M13 |

M14 |

M15 |

M16 |

| Intercept |

3.002*** |

1.860*** |

0.335*** |

0.421 |

3.336*** |

2.172*** |

1.303*** |

1.330*** |

| Gender |

-0.136 |

-0.156** |

-0.203*** |

-0.189** |

-0.106 |

-0.107 |

--0.084** |

-0.083 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Education |

0.299*** |

0.211*** |

0.215*** |

.204*** |

0.163*** |

0.173*** |

0.169** |

0.168*** |

| Work Experience |

-0.056 |

0.011 |

0.016 |

0.016 |

0.001 |

0.017 |

0.014 |

0.016 |

| Length of employment |

-.013 |

-0.002 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.035 |

0.043* |

0.046 |

0.047 |

| Job position |

0.106 |

0.126 |

0.126 |

0.113 |

-0.135 |

-0.117 |

-0.115* |

-0.116 |

| J-Hopping Times |

-0.039 |

-0.089* |

-.086* |

-0.079* |

-0.052 |

-0.053 |

-0.037 |

-0.038 |

| POQ |

|

0.374*** |

0.359*** |

0.355*** |

|

0.306*** |

0.301*** |

0.302*** |

| DL |

|

|

0.445*** |

0.428*** |

|

|

0.228*** |

0.218** |

| POQ x DL |

|

|

|

.319*** |

|

|

|

0.062 |

| R2 |

0.147 |

0.313 |

0.382 |

0.406 |

0.088 |

0.255 |

0.282 |

0.283 |

| ∆R2 |

0.122 |

0.290 |

0.358 |

0.380 |

0.060 |

0.228 |

0.252 |

0.250 |

Discussion

This study utilized data from 596 questionnaire responses and found that the sense of overqualification (POQ) promotes employees' constructive deviant behavior (CDB). When an employee’s personal qualifications exceed job requirements, they may feel that their ideal self and developmental expectations are unmet in the current work context. This enhances their "Can do," "Reason to," and "Energized to" motivations, leading them to exhibit CDB. This finding aligns with the results of Arvan’s (2019) study.[

26] Additionally, the effect of POQ on promoting CDB varies across generations. It is strongest for employees born in the 1980s and weakest for those born in the 1970s. This may be attributed to individual characteristics, values, beliefs, and expectations, particularly cognitive differences.[

20] The study also found that digital leadership (DL) plays a moderating role in the relationship between POQ and CDB, and this moderating effect differs across generations.

Theoretical Implications

A substantial body of research, including both primary studies and narrative reviews, has laid the theoretical groundwork for the literature on perceived overqualification (POQ).[

16,

27,

28] This study builds upon and enriches the theoretical foundation by exploring how POQ influences employee behavior and by validating the explanatory power of the proactive motivation model in this context. Previous research on POQ was primarily grounded in theories such as person-environment fit, relative deprivation, and equity theory, often leading to conflicting conclusions. In contrast, this paper applies the proactive motivation model to explain the behavior of overqualified employees through the concepts of "Can do," "Reason to," and "Energized to," marking a significant departure from prior studies.

Secondly, this study broadens the research perspective on POQ and CDB by examining generational differences. Previous academic research has shown that employees from different generations display distinct organizational behaviors due to variations in values, even within the same organizational context.[

20,

29] However, few studies have thoroughly investigated organizational behavior from the lens of generational differences. This study highlights the significance of generational differences, offering a new dimension to understanding POQ and CDB, thereby marking a second distinction from prior research.

Finally, the study emphasizes the role of work context and leadership in shaping employee behavior, reaffirming the critical influence of leadership styles. The findings demonstrate that DL moderates the behavior of employees who feel overqualified, particularly those born in the 1970s and 1980s. This outcome aligns with existing research, which underscores the importance of leadership in influencing employee actions.[

21]

We believe that the most significant contribution of this paper lies in its focus on the issue of generational differences. While much of the existing academic research has concentrated on studying work values related to generational differences, most of this research has been primarily descriptive and lacks strong theoretical support.[

29] As individuals born in the 1990s and 2000s increasingly enter the workforce, generational differences in the workplace have become more pronounced. Both practical experience and theory suggest that employees from different generations exhibit substantial differences in their lifestyles, learning preferences, and approaches to work. By examining POQ’s impact on CDB through the lens of generational differences, our study has uncovered more nuanced mechanisms that influence this relationship. This perspective offers new avenues for academic inquiry, as we believe that any issues related to psychology and values should be examined through the generational lens.

Practical Implication

The conclusions of this study have significant implications for enterprise managers, particularly human resource managers, who aim to conduct high-quality human resource management. The findings can help managers more effectively manage employees experiencing perceived overqualification (POQ). First, managers should adjust their management philosophies and develop a nuanced understanding of deviant behavior, particularly constructive deviant behavior (CDB). It is crucial to establish flexible and resilient institutional mechanisms that balance formal and informal rules, maintaining a dynamic equilibrium between the two. Managers should recognize the inevitability and potential benefits of positive informal behaviors and deviance, actively learning and exploring ways to positively harness these behaviors. Second, managers must foster an open and creative environment, providing employees with more opportunities and platforms for innovation, thereby utilizing employees' excess qualifications to improve workforce quality. As Ginevicius (2020) pointed out, insufficient workforce quality can hinder economic growth when it fails to meet market demands.[

30] Therefore, managers need to understand the real concerns and motivations of employees with excess qualifications, create the necessary conditions for them, and guide their talents effectively. By doing so, managers can mitigate the issue of qualifications surplus, uncover potential learning opportunities, and continuously enhance workforce quality. Third, managers should not only cultivate digital leadership (DL) but also conduct structural analyses of their workforce to better understand intergenerational differences. Special attention should be paid to generational differences in employees' perceived overqualification, constructive deviance, and perceived fairness, among other factors.

Limitations and Future Research

As with most studies, our research has limitations. Due to constraints in resources and time, we were unable to strictly adhere to stratified sampling. While random sampling or selecting representative samples are viable alternatives, these methods may compromise the generalizability of the research findings. In future studies, it would be advisable to conduct a more scientifically rigorous sampling process to enhance the representativeness of the data.

Furthermore, this study focused on generational differences among employees born in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. However, some individuals born in the 2000s have already entered the workforce. Since most of them are in their early career stages, such as their first year of employment or internship, their work situation is relatively unstable, and they were therefore excluded from this study. Nevertheless, as more members of the 2000s cohort enter the workforce, it will be essential to explore their perceived overqualification (POQ) and behavioral dynamics in future research.

Conclusions

In this study, we applied proactive motivation theory to examine the relationship between perceived overqualification (POQ) and constructive deviant behavior (CDB), along with the moderating effect of digital leadership (DL). Additionally, we explored the generational differences within these relationships. The results aligned with our expectations and were largely supported by the data. In conclusion, the study suggests that perceived imbalances in organizations, such as overqualification, can contribute positively to organizational development, provided that managers handle them effectively.

Ethical Statement

The study followed the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration 1964 and its subsequent amendments. In addition, all participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Ethical Statement

The study followed the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration 1964 and its subsequent amendments. In addition, all participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

References

- Erdogan, B., & Bauer, T. N. Perceived overqualification and its outcomes: The moderating role of empowerment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009; 94, 557–565. [CrossRef]

- Maynard, D. C., Joseph, T. A., & Maynard, A. M. Underemployment, job attitudes, and turnover intentions. J. Organ. Behav. 2006; 27, 509–536. [CrossRef]

- Erdogan B, Bauer T, Peiró J, Truxillo D. Overqualified Employees: Making the Best of a Potentially Bad Situation for Individuals and Organizations. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2011; 4(2):215-232. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D. C. The nature, antecedents and consequences of underemployment. J. Manage. 1996; 22(3), 385–407.

- Johnson, W. R., Morrow, P. C., & Johnson, G. J. An evaluation of a perceived overqualification scale across work settings. J. Psychol. 2002; 136(4), 425–441. [CrossRef]

- Luksyte, A., Spitzmueller, C., & Maynard, D. C. Why do overqualified incumbents deviate? Examining multiple mediators. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011; 16(3), 279–296. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K. W., Shea, T. H., Sikora, D. M., Perrewé, P. L., & Ferris, G. R. Rethinking underemployment and overqualification in organizations: The not so ugly truth. Bus. Horiz. 2013; 56(1), 113–121. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M J, Law A S, Lin B. You think you are big fish in a small pond? Perceived overqualification, goal orientations, and proactivity at work. J. Organiz. Behav. 2016; 37,61–84. [CrossRef]

- Vadera, A. K., Pratt, M. G. & Mishra, P. Constructive deviance in organizations: Integrating and moving forward. J. Manage. 2013; 39(5),1221-1276. [CrossRef]

- Galperin BL, Burke RJ. Uncovering the Relationship Between Workaholism and Workplace Destructive and Constructive Deviance: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2006; 17:331-347. [CrossRef]

- Wang T D, Lin X Y, Sheng F. Digital leadership and exploratory innovation: From the dual perspectives of strategic orientation and organizational culture. Front. Psychol.2022; 13, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P. Digital Master: Debunk the Myths of Enterprise Digital Maturity.Morrisville, NC: Lulu Publishing Services. 2015.

- Ma C, Lin X, Chen ZX, Wei W. Linking Perceived Overqualification with Task Performance and Proactivity? An Examination From Self-concept-based Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020; 118: 199–209. [CrossRef]

- Liang H, Li XY, Shu J. The Impact of Overqualification on Employees' Innovation Behavior: A Cross Level Adjustment Model. J. Soft Sci. 2019; 33:122-125. [CrossRef]

- Dijka HV, Shantzb A, Alfesc A. Welcome to the Bright Side: Why, How, and When Overqualification Enhances Performance. Hum. Res. Manage. Rev. 2020; 30(02): 004. [CrossRef]

- Parker SK, Bindl UK, Strauss K. Making Things Happen: A Model of Proactive Motivation. J. Manage. 2010; 36(4):827-856. [CrossRef]

- Song ZY, Gao ZH. “Well-balanced Tension and Relaxation” Is Powerful for Innovation—A Dual Moderating Model of the Relationship Between Coaching Leadership and Employees' Innovative Behavior. Res. Econ. Manag.2020; (04):132-144.

- Mertens W, Recker J. How Store Managers Can Empower Their Teams to Engage in Constructive Deviance: Theory Development Through A Multiple Case Study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020; 52:101937. [CrossRef]

- Liu XP. The Formation Process of Employee Organizational Commitment: Internal Mechanism and External Influence-An Empirical Study Based on Social Exchange Theory. J. Manag. 2011; 11:92-104. [CrossRef]

- Meng XL, Chai PF, Huang ZW. Work Values, Organizational Justice, Turnover Intention and Intergenerational Differences. Sci. Res. Manag. 2020;41(06), 219-227. [CrossRef]

- Su XY, Su J, Tian HY. The Intergenerational Differences In Employee-Organization Values Fit and Their Impacts on Challenging Organizational Citizenship Behavior.J. Ind. Eng. Manage. 2021;35(05): 26-40.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979; 47(2), 263-291. [CrossRef]

- Peng XL, Yu K, Peng JF, Zhang KR, Xue HB. Perceived Overqualification and Proactive Behavior: The Role of Anger and Job Complexity. J. Vocat. Behav. 2023; 141:103847. [CrossRef]

- Khan J, Saeed I, Zada M, Nisar HG, Ali A.Zada S.The Positive Side of Overqualification: Examining Perceived Overqualification Linkage With Knowledge Sharing and Career Planning. J. Knowl. Manage. 2023; 27(04): 993-1015. [CrossRef]

- Galperin BL, Burke RJ. Uncovering the Relationship Between Workaholism and Workplace Destructive and Constructive Deviance: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2006; 17:331-347. [CrossRef]

- Arvan, ML, Pindek S, Andel SA, Spector PE. Too Good for Your Job? Disentangling the Relationships Between Objective Overqualification, Perceived Overqualification, and Job Dissatisfaction. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019; 115(6):103323. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Bolino MC,Yin K. The Interactive Effect of Perceived Overqualification and Peer Overqualification on Peer Ostracism and Work Meaningfulness. J. Bus. Ethics. 2023;182: 699–716. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wu MR, Li NN, Zhang M. Dual Relational Model of Perceived Overqualification: Employee's Self-concept and Task Performance. Int. J. Select. Assess. 2019; 27:381-391. [CrossRef]

- Joshi A, Dencker JC. Franz G. Generations in Organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2011; 31(0):177–205. [CrossRef]

- Li GP, Chen YY. “The Influence of the Perceived Over Qualification on the Innovation Behavior of the New Generation of Post-90s employees”, Sci. Res. Manage. 2022; 43:184-190. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).